University of South Carolina Faculty & Staff Study Abroad Program South Africa Spring Break 2017

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

South Africa was never on my bucket list of countries to visit. I knew very little about the people, the culture, or the geography. I knew of apartheid and Nelson Mandela, but honestly, eating worms and banging on drums was not a high priority for me. I became interested in leading a study abroad trip after one of my students participated in a trip to China in December. Having lived in Germany for 3 years, I was well aware of the benefits of living in another country and learning about the people and the culture. I wasn’t sure how much I could learn about Africa in just 5 days, but I was open to learning. What I didn’t anticipate was how much I would learn about myself and my privileged life. The Privilege of Being a Tourist – From the moment our plane landed in Johannesburg, we began a week-long journey to cram as much of South Africa as we could into 5 days. This meant spending a great deal of time on a bus and trying to keep to a very tight schedule. We had a tour guide who told us where to go and when to be there so we really didn’t have to think much for ourselves. In our hurry to be on time, we expected fast service and for servers to do things our way, like split the check, because it made things easier for us. We attempted to stay together as a group so we didn’t get separated and expected others to move out of our way as we moved down side-walks often walking on the wrong side of the walk. We took pictures of people and places and things without really interacting with the South African people or getting to know them. We bought their souvenirs to bring remember the trip, but we know little about the person. We made assumptions about their life based on our stereotype of people from the area. I wish I had taken more time to be a “participant-observer” saying hello and learning more about the individuals I encountered along the way and spent less time taking pictures and collecting treasures. The Privilege of Being Able-bodied – In our haste to see everything from colleges to tourist attractions we did a lot of walking. We took the shortest route between two points which often meant walking along bricked sidewalks and taking lots of steps. I had the option to use a number of different restrooms along the way and I was not limited to only one restroom in an out of the way location. I could easily follow the crowd and keep up with the group, but it wasn’t that easy for everyone. I learned there are a lot of things in my life I take for granted, every single day. Being in a new location and hearing a language I didn’t recognize forced me out of my comfort zone. I had to pay much more attention to where I was going and how I was getting there. I became afraid when I was separated from the group and constantly worried about what would happen if I got lost. I didn’t recognize my surroundings and had no idea of how to get back to an area I knew. I imagine this is how students with disabilities feel when they are trying to go somewhere and they don’t know where the accessible route is or that route is blocked. They can’t read the signs that tell them where to go or how to get there. Fear can be an overwhelming experience that keeps us from moving forward. The Privilege of Being a Part of this Group – What I did learn from being a part of this group has changed my life in ways I never anticipated. From our conversations at the colleges and universities I learned that they make a conscientious effort to deal with discrimination in all of its forms EVERY – SINGLE – DAY. Truth and reconciliation is a way of life for the people of South Africa, not something they celebrate one month of the year. The administration on many campuses take reconciliation seriously, they have goals, they measure it, they don’t take it for granted. They focus on helping those who have less, and helping to improve their lives through education and better jobs. While the country has come a long way toward reconciliation since 1990, there is still a long way to go toward equity. The colleges and universities we visited see that they can play a key role in bringing about change and they are willing to do their part. I learned that I have friends who care about the work that I do with students with disabilities, they saw examples of accessibility and inaccessibility and pointed these out to me. For the first time in a long time I didn’t feel like the invisible employee but included in the conversations and that the students I work with were valued in this group. Each of us came to South Africa with our personal beliefs and individual mind-set about race in South Africa and in South Carolina or Georgia. After each day’s experiences, we had the opportunity to share our thoughts and feelings as a group. We learned the importance of being able to speak openly and freely in a safe and respectable environment. I saw people confront their own biases and prejudices without being judged by others. We recognized various forms of discrimination on our own campus and discussed ways we could work together in the future to confront racism and discrimination. As for me, I learned the greatest souvenir of all was the new friendships I made that will last me for a lifetime. Karen Pettus

1 note

·

View note

Photo

STILLNESS OF THE MIDNIGHT

“I want daytime, I want place, I want a sense of history. Even though place will never be the same again for me, because its lights and shadows may change, I want to be there when it happens.” Es’kia Mphahlele, 1984

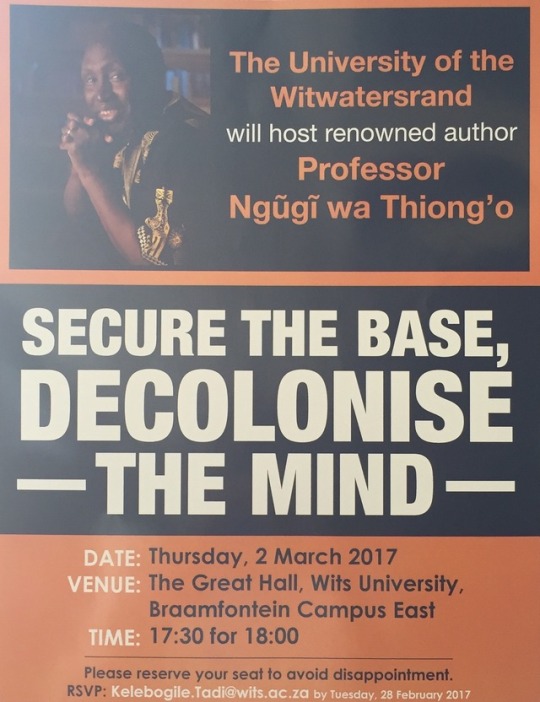

As I write, I am leaving Johannesburg on a flight bound for New York City’s JFK Airport. This unbelievable visit to South Africa is coming to an end. Honestly, I should have written this post days ago, but the mental and physical energies needed to process all that I have seen and felt escaped me. What an inspiring and sobering experience this journey has been. In the weeks leading up to our travels to Joburg and Cape Town, an image of a bespectacled elderly gentleman with white hair remained frozen in my mind. Nearly fifteen years ago, in a sparse office lit only by the sunlight of the windows, he sat quietly writing on a lined notepad. We were neighbors in Gambrell Hall where he served as a visiting fellow. To many, he was just an older instructor with a slow gait dressed in African clothing. Few knew that he was Dr. Es'kia (Ezekiel) Mphahlele, one of the most highly regarded literary writers and intellectuals from the African continent, hailed as the “Dean of African Letters.” In a memoir entitled Down Second Avenue, Es’kia wrote powerfully about the racial segregation and discrimination of his youth in Pretoria. When he passed away in 2008, I regretted that I never had a chance to visit with him in his native home. While I learned many details about apartheid in college and graduate school, the full power of the human and civil rights campaign among people of African descent was pressed upon me by Es’kia’s wise guidance. As our IPHE cohort made our way to various destinations, I thought about Es’kia and the conversations we had in his office. As he called the roll of friends and associates—W. E. B. Du Bois, Malcolm X, Langston Hughes, and Leopold Senghor—, I peppered him with endless questions. And he very graciously satisfied my schoolboy curiosities. Sitting on the air-conditioned bus zipping down streets and highways, I thought about Es’kia as I looked at the expansive compounds and humble corrugated tin structures—most bounded by walls, wires, and gates. I wondered what Es’kia would have to say about these divided encampments two decades after the fall of apartheid. How would he respond to the pronounced dissonance, fears, and frustrations that continued to strangle the hopes and aspirations of so many? What would Es’kia say about the seemingly insurmountable hurdles children from his homeland faced as they scaled the ladders of higher education? What words of encouragement would he offer the young lady next to me on this flight—a pre-med student at the University of South Africa who is on her way to a United Nations conference. I know Es’kia would be quite proud to hear of her work empowering young women living in Alexandra, an impoverished township near Joburg. As our group studied higher education in Johannesburg, I’m sure Es’kia would have given us a very different orientation to institutions, especially the University of Witwatersrand. While students rightly protested the soaring costs of education and demanded a “decolonized” curriculum at Wits and elsewhere, I wondered how many of them knew about Es’kia Mphahlele. Did they know that this extraordinary scholar and activist navigated minefields as Wit’s first black African professor? Did they know of his pathbreaking demand for decolonization as he shaped the formation of African Studies? Ironically, while meeting with Wits faculty members, Janet Hudson, Chris Ward and I spent time with Dr. Sekibakiba Peter Lekgoathi, the head of the History Department. When I mentioned Es’kia’s name, a bright smile came across Professor Lekgoathi’s face. He told us he was one of Es’kia’s former students, and he spoke movingly about his teacher’s influence as a mentor for the black African undergraduates and graduates who broke down color barriers on the campus. As we entered Soweto, the South Western Township, and traveled down a palm lined highway and passed shopping malls, fast food restaurants, and new car lots, I thought of Es’kia. I thought of his resting place in Limpopo as I tried to make sense of the faded inscriptions on headstones in an overgrown cemetery on the side of the road. As I looked toward distant hills and counted rows upon rows of small homes (others called them shanties) dotting the horizon, I thought about the stories that Es’kia shared. What testimonies, what secrets and what revelations lingered among the people who lived in those places? Here was the township where Es’kia lost his teaching job for opposing Bantu schools—convinced that such schools were designed to keep his people down. Here was the terminus of the forced migration of “many thousands gone,” a place where Black Africans were banished to the margins as “pilgrims in a barren land.” Here was the home later occupied by a former teenager trained to box by Es’kia. In the years to come, we would know the young boxer as Archbishop Desmond Tutu. A sense of guilt and anxiety came over me, as l looked out the bus window—making note of the landscape, dwellings and people before me. As we toured Soweto, I so wanted the bus to be quiet as my mind took in the scenes before us. But some of the voices of my colleagues kept breaking the silence. I wanted to sing: “Hush, somebody’s calling my name.” Don’t you see what I see? Don’t you feel what I feel? Don’t you know where we are? Aren’t you searching and seeking like me? Think of this! A luxury bus driving by a Soweto family traveling by horse and wagon. Dirt roads with gapping potholes only feet from the paved street that carried United States tourists by tiny metal homes, small gardens, clothes swinging in the wind near outhouses, joyful children coming home from school, goats foraging along the roadside, men sipping wine in front of a barbershop, a bouncing baby sitting with his parents selling vegetables in the market, only steps away from the memorial commemorating the 1955 Freedom Charter, a document with prophetic words from sixty-two years ago that read: “There shall be houses, security, and comfort.” Throughout my time in Soweto, I found myself stepping to the side, walking in solitude, touching walls and stones, looking down side streets, listening to voices—speaking languages that I did not understand. Indeed, it was a moving picture. Moving in the emotional sense. But also moving in the cinematic sense, like watching a film from my window. But the scenes were not lifted from a Hollywood script. There were as real as real could be. One of the most striking persons I encountered was an elderly woman with a brown cap that touched just above her furrowed brows. Her eyes, her complexion, and her cheekbones reminded me of my grandmother Helen. She had on a light blue spotted dress, a red shirt and dark blue slippers. Lying almost prostrate, her weathered hands weeded a small dirt spot in front of the Regina Mundi Catholic Church. More than a place of worship, this holy dwelling served as a site of protest during the height of the Anti-apartheid struggle. Here Freedom Fighters found sanctuary and security as the defenders of white power attacked them with guns and batons. Here the markings of bullet holes near the altar illustrate the cruel limits people would go to defend the status quo. And here in the shadows of a church amid vendors and tourists, an elder pulled weeds from a dirt plot. A beautiful moment happened as I watched members of our group drop to their knees to assist the woman. And there hands of many colors picked away at what was left of the green leaves in the dirt patch. The work was done, and the plot was like new again. After we spent time buying souvenirs from the vendors, our bus prepared to continue on our journey. As we departed, I looked back at the woman who reminded me of Grandma Helen. And there she was—still on the ground, her gaze downward and her hands still touching the dirt in the cleared little patch. Was she touching with pride the work she accomplished with help from the visitors? Or were her fingers pulling away at the hidden roots that my friends overlooked? Maybe her seasoned eyes saw something in that soil that we did not. Maybe! I so wanted to talk to her and learn more about her life. Who was she? Why was she on the ground in front of a church pulling away weeds? Unanswered questions. Her face and her countenance, her clothes and her grin were all so familiar, and yet we were complete strangers, separated by time, distance, language and history. Maybe the woman with her fingers in the little patch of dirt could tell us what happened to Hector Pieterson and the young people killed in 1976. Was she there? Did she know any of those young souls gunned down as they protested? Next to the Pieterson Museum, our delegation of educators tried to make sense of the harrowing story before us. With cascading fountains and a gripping image of a lifeless Pieterson in our background, Poloko Nthako, our tour guide powerfully chronicled the tragic death of hundreds of young students—freedom warriors—who were crucified daring to believe that their future could be different. Beneath a reflecting pool of rocks and slated stones, there was an arresting line: “To honour the Youth who gave their lives in the struggle for freedom and democracy.” Hector Pieterson killed on a Soweto street. Nelson Mandela locked away in a tiny cell on Robben Island. Es’kia Mphahlele writing and teaching exiled across the sea. The elderly woman dressed in many colors in front of her church. And the bright young woman sitting next to me on this flight whose mother saves from a teacher’s salary so that her daughter might one day become a pathologist. Juxtapose all of this to a historic sign that confronted me and boiled my indignation when we visited the Apartheid Museum in Joburg. The words were plain and simple. They echoed the troubling fears of white people and underscored the depths of oppression black people faced. “The White man is the master in South Africa, and the white man, from the very nature of his origins, from the very nature of his birth, and from the very nature of his guardianship, will remain master in South Africa to the end.” MASTER TO THE END? This was the tragic history that Es’kia wanted to expose. In only a few days, this trip demonstrated that such absolutes--described so often as “natural”--have a way of being uprooted, just like the weeds in front of the Regina Mundi Church. We see clearly that South Africa is a different place. And yet, the people remind us that there is a difficult, bruising, and badly needed struggle ahead. Lessons learned. Hopefully so! My seat mate is now asleep, and I should follow her lead. A notebook and a small Bible are in her lap. So, I dim the lights, turn on my I-tunes, and listen to Aretha Franklin’s version of a gospel song my friend Absalom and I used to sing during our first year in college—the same year we donned our black uniforms and championed the anti-Apartheid Movement in that far distant place called South Africa. “Precious memories, how they linger, how they ever flood my soul. In the stillness of the midnight, precious sacred scenes unfold.” -Bobby Donaldson

1 note

·

View note

Text

Johannesburg, City of Walls

We've heard a lot of talk, in the United States of America, about building a wall over the course of the last two years. In visiting Johannesburg, South Africa, we saw a major city with walls everywhere.

Johannesburg is a city of walls: walls with sturdy gates and locks, walls made of wood, metal, bricks, bars, concrete and stone. Those constructed from metal bars tend to have wicked looking barbs or points at the ends. Many others have multiple strands of electrical wiring gracing the top of the wall, while others sport lengths of razor wire. These walls, along with private security firms (boasting armed response) and dogs, surround Hollywood-style houses, modest homes, apartment buildings, nearly all free-standing businesses and even small strip malls and shopping centers.

As a direct result of the apartheid system, the main parts of the city were populated by the white minority and those people of black African descent and any variety of mixed racial background were relocated, forcibly, to the outskirts of Johannesburg. It appears to have remained so, to this day. But the walls are not confined to the white center of the city. The township of Soweto is also surrounded by walls, whether nice family dwellings or the shacks put together of whatever scraps were available. They may not have indoor water, but they have a fence.

One of our tour guides, a South African man of mixed race, was gracious enough to answer some of my questions about this. As in many other communities, throughout the world, Johannesburg always had fences. It probably feels like a necessity, when you are part of a ruling minority and the majority population is starting to push back and demand (at the very least) some say in how their country will go forward. At any rate, he said that the fence building really took off around 1990, when President F. W. Dr Klerk began negotiating for the release of Nelson Mandela from prison, sparking serious fear of both civil wars and a race war. There was violence, following Mandela's release, some of it incited by state security forces, but the full-scale race war that many expected, never materialized. Yet, the walls remain.

There are concerns that need to be addressed to move South Africa forward, to be sure. Boasting the top economy in Africa for many years, the big cities (especially Johannesburg) have attracted millions of immigrants from poorer African countries, looking for a better opportunity. In a country with 26% unemployment, opportunity is not easy to find, and South Africans resent their presence there, another parallel to some concerns in the U.S. You don't have to look hard to find homeless people, beggars and streetside entrepreneurs. There are also panhandlers and hustlers in the middle of busy intersections, approaching stopped vehicles to sell their merchandise. And of course, those who resort to crime. The walls may provide a barrier to being directly affected by these problems, but they do nothing to address them.

That the institution of apartheid was ended and a new government and constitution installed in South Africa, relatively peacefully, has been described as miraculous. But to really own the description "The Rainbow Nation"--I think that there are still a lot of walls that have to come down.

Marilyn McManus

1 note

·

View note

Text

Differences. Commonalities. Oblivious. Well, our time in South Africa is drawing to a close. We came to South Africa to study apartheid and its effects on higher education. As part of doing that, we've experienced South African culture and taken note of its diversity. We've discussed the differences and similarities between our culture and South African culture. It's good to understand other cultures and how we are different. It promotes tolerance and acceptance of each other. However, I think sometimes we tend to focus more on the differences between cultures than what our cultures have in common. Trevor Noah said speaking the same language allows people to communicate, but speaking to another person in THEIR language creates trust and understanding -- allowing them to bond. This statement was reinforced by a man I sat next to at the Ladysmith Black Mambazo concert that a number of us attended before our trip. Though he was born in the United States and was a US citizen, he had lived and worked in South Africa for over 30 years. He told me (unsolicited) that the surest way to create strife and divisiveness among people was to make them speak different languages. Languages segregate people. I'm friends with someone that -- when I think too much about it -- I have very little in common with. In all honesty, I've asked myself "Why am I friends with this person? We're on the extreme opposite end of the political spectrum and we don't really have any of the same hobbies." And yet, we're friends. We've supported and comforted each other through the deaths of our fathers and his brother. We work together on church projects. We, along with two other friends who are more in line with his political beliefs, recently enjoyed a guys night out drinking beer and attending the Book of Mormon together. So what do we have in common? We're both avid Clemson fans and we share a common faith. (Just to be clear, I love working at USC and promote the university and it's programs without hesitation. I attended Clemson 7 years as an undergraduate and graduate student earning two degrees, but I also graduated from USC. So, I think I have both schools covered!) We both recognize and understand our differences, because we've talked with each and gotten to know each other. But, we have also identified our commonalities so can bond as friends while being tolerant and accepting of our differences. Thursday night our group went to a local vineyard in Cape Town that was having a festival. Numerous food vendors were there cooking and selling food. Obviously, lots of wine was being consumed too. I was eating with another man and Hispanic woman, when the Hispanic woman said that "this is a white person's place." I looked around and saw that aside from members of our group, there were only white people attending the festival. She was right! It hit me that I was oblivious to the racial segregation occurring right in front of me. To me, it was no different than other events I had attended as a white male during my lifetime. It hit me HARD. The reason it hit me so hard is because I thought I was enlightened. I had always treated others with the kindness and respect that I would want to be treated. I had never ever used a racial slur and neither had my wife. We had raised our children to do the same. When I was in college, I had gotten fired from a summer job as a farm laborer because I had refused to enable my employer's racist treatment of some other black laborers. After college, I worked with and cared deeply for fellow black employees. I was one of only four white wrestlers on my wrestling team -- the rest of the team were black wrestlers and I got along with all of them. I had done all these things and more. Then, I realized that a black person had never eaten supper with me in my house. I realized that all those things I had been doing my entire life didn't make me enlightened. That all those things weren't enough. That I didn't get it. That I didn't understand how minorities perceived racism. The only way for us to understand each other is to identify our differences and commonalities by talking with each other. Talk and get to know each other. Only then can we bond. Our group this week is a very diverse group of people. As our week ends, I'm grateful for the opportunity to get to know so many of the people in the group. (I apologize in advance if I forget names in the future. Please be assured that, while I may forget names, I don't forget people.) I celebrate both our differences and the things we have in common. Focusing on understanding our differences may foster tolerance and acceptance, but focusing on things we have in common fosters bonding. My hope for South Africa, and our own country in the future, is that we both continue to find common ground with each other through which people can bond. Steve Slice

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Learning humanizes character and does not permit it to be cruel." This is our university motto and it has been playing on repeat in my mind this week. The learning that occurs when you are taken out of your comfort zone is challenging, difficult, and life changing. This week many of us have been taken out of our comfort zones, whether it was rooming with others, being stuck in a plane for 16 hours, trying exotic foods, or discussing very difficult topics. I have been learning and thinking so much during this trip and I am happy to share some of my thoughts and questions, as well as recap of our day. I came into this trip thinking I would be focusing on the differences between higher education in the U. S. and South Africa. Instead I have been shown the similarities. I am saddened when I realize that a country that is only 20 years post apartheid faces similar issues to us-when we are 53 years out from the Civil Rights Act being passed. White privilege is a glaring similarity of South Africa and the US. What will it take to finally dismantle it? Additionally, how can we channel white guilt into empathy instead of anger and denial of racism? Will this ever truly happen? Earlier this week we visited the University of Johannesburg and I noticed they had banners up around campus with different quotes. One of them was a Tibetan proverb: "A child without an education is like a bird without wings". I am continually frustrated with how inaccessible higher education is to students in the U. S. South Africa also faces this issue. We continue to clip the wings of the poor and underprivileged when we make higher education unaffordable and unattainable. Decolonization of higher education is another theme that we have heard from every university on our trip. The universities want a more Afrocentric education system instead of relying solely on western thought. This makes me think about our own education system where slavery is romanticized and many people balk at Black History Month. While higher education in South Africa is trying to form it's own identity, the US is at odds with itself and can't even tell the real truth about our past. This morning we were greeted with a beautiful South African sunrise on our drive to the airport. Getting through check-in and security was a breeze. After a quick flight to Cape Town we landed, gathered our luggage, and boarded the bus. On the way to lunch we passed one of the poverty stricken communities of Cape Town. People live in shacks constructed of metal sheets, with a sheet across the top for a roof. On top of the roof are rocks, tires, or any other things that could be used to keep the roof on. Rising up behind these shacks is Table Mountain, a striking and beautiful mountain. It seemed to me that the juxtaposition of the tall, grand mountain rising up behind the shacks could be a metaphor for the hope and spirit that South Africans possess despite the horrors the country has endured. After a quick and delicious lunch at the Rhodes Memorial, we made our way down to the University of Cape Town (UCT) where we were given an introduction to the university and information about the education system in South Africa. Afterwards we had a chance for networking with UCT faculty, and some delicious snacks. Following our refreshments we had a campus tour. UCT is a lovely campus that sits on a hillside overlooking Cape Town. One of my favorite parts of the tour was hearing Njeri, our tour guide, talk about the student protests that were happening last fall and how the university is trying to address the student concerns-many of which deal with lingering issue of apartheid. Leaving campus we had the most scenic drive to our lodging! We are staying on the beach and the sea breeze is just what we needed after a long, hot day. For dinner we went to Cape Point Vineyards where we enjoyed wine and food while watching the sun set. It was lovely to fall asleep last night to the sounds of the wind and ocean. I am excited and thankful for another day in South Africa. -Rebecca

0 notes

Text

Familiar but Different

We’re on the bus heading to the airport at 5:30 Thursday morning--destination Cape Town. The captive time in the plane allowed reflection time on our Joburg experiences. I've experienced South Africa as both familiar and unknowable. English is pervasive, making South Africa easily navigable for an English-only speaking American like myself, yet the country has 11 official languages. The majority of South Africans are bi-or-multilingual, and English is not their first language. Highways are large, fast moving, congested with the traffic of the familiar brands of Toyota, Mercedes, VW, BMW, Chrysler, and Ford, but SUVs are rare and among the overwhelmingly small cars you also find Pegots and other less familiar brands. And all, of course, driving on the "wrong" side of the road, a legacy of British dominance in the early 20th century.

Joburg, a world class city, offers numerous large shopping malls with ample extravagances, restaurants of all kinds, and familiar brands such as Forever 21 and Samsung. Yet in Soweto, a community created in the Apartheid era to house African laborers needed to make Joburg function, many residents access the basics of life in an outdoor market and sell local crafts as souvenirs to tourists like ourselves who come to Soweto to learn about and honor the freedom struggle of those who resisted Apartheid's oppression. Jarring and unfamiliar is the pervasive presence throughout Johannesburg of walled homes topped with electrified fences with notification of armed security. These warnings reveal numerous private security firms such as Ghost Squd, Bengal Patrol, ADT, Suburban Neighbor Protection, and a host of other names seeking to normalize deadly force to protect the private property of the minority "haves"in a woefully unequal society. In South Africa, minority means "white." While that is obvious and well known, it turns the concept of "minority" on its head in an American context. At the Apartheid Museum, we explored, in part, the legacy of racial oppression constructed by the white minority. The South Africa we have experienced this week is two decades into constructing a very different society that honors the many people of Africa, especially the indigenous black Africans. That journey to realizing full equality will be long. In many ways it feels very familiar, almost an American story, yet the scale and scope is quite different and difficult for an American, at least this one, to access.

Janet

0 notes

Photo

Yale Rd. to honor the planetarium they donated to Wits

0 notes

Text

Wities and Safaris

Day 2 started with a great breakfast at the Apollo Hotel and then we were off to the University of Witwatersrand Johannesburg. Referred to as "Wits," the University was founded in 1922. It was originally known as the College of Engineering and Mining. Wits is known for its study in Paleo Sciences and is home to the largest collection of African art, in the world. Wits has 33, 000 students enrolled. This year, 6,500 new students were accepted out of 90,000 applications for admission! Wits was ranked the number one university in South Africa last year and accepts the top 4% of high school students. After we entered the security gate and walked onto the campus, we could get a good feel for the campus. It was obvious that Wits has more resources than the University of Johannesburg. The facilities and grounds were well-maintained. It reminded me very much of USC! The campus was very active! There were students in class, holding study sessions, hanging out and protesting! Wits was and is home to some very prestigious individuals! Nelson Mandela attended law school here, but as unable to finish because of apartheid. Wits is also home to Leisl! Leisl was a student spotted in the cafeteria, sporting a Gamecock hat!! Of course we all had to get pictures with him! He had previously visited Columbia and our campus! We separated into groups and heard from campus officials with roles similar to our respective areas. Ms. Lindiwe Manyika, Director of Transformation and Employment Equity, shared the plans that Wits has to provide and improve access and services to underrepresented individuals. It was interesting to hear that many of the initiatives they implemented were very similar to things we are doing at the University. Our group was granted a free afternoon. Some decided to go shopping, some visited a museum and others went on a safari! Today was busy and very fulfilling. Althea

0 notes

Text

Day 2

Today we visited the University of Witwatersrand. It's a beautiful, buzzing green campus in the middle of Johannesburg. Students were engaged everywhere we went: rushing to class, lunching outside with friends, peacefully protesting on the main lawn, creating street art in the tunnel between East and West campus. We ran into a South African student who had been at USC -- Gamecocks are everywhere! "Wits" (pronounced "Vits") is a top university in the country and on the continent, focusing more and more on doctoral teaching and research. We had the chance to meet with our individual counterparts, and discuss how higher ed has changed post-apartheid. The challenges we heard about seem matched by the vision and determination of the South African people. Wits slogan is, "Building Lives, Transforming a Nation, Advancing a Continent." We enjoyed the outdoor sculptures all across campus. Several of us visited two amazing Vits museums -- one on the origins of humankind and also the Wits Art Museum. Uber works well for getting around the city. Day 4 ended with dinner outside on a perfect summer evening --great to be in the Southern Hemisphere in March! --Helen

0 notes

Text

We enjoyed an informative and fun first day in Johannesburg. After waking up to sunshine and brillant blue skies, our very congenial group embarked on a tour of Johannesburg University and meetings with various faculty on campus. They were such gracious hosts. I think that I can speak for most members of our group when I say that we left with a better understanding of higher education in South Africa, but also with many questions about the impact and recovery from Apartheid. Fortunately one of our ground leaders offered us an insider's view from someone who lived through the final chapter of Apartheid. He is also going to help facilitate conversations with a few individuals in the community who will give us a perspective from those who suffered under Apartheid. Our group is looking forward to these conversations later in the week. One of the highlights of my visit to the University of Johannesburg was meeting one of our Arts and Sciences Alumna, who serves on the faculty at UJ. This evening we enjoyed a traditional African Meal, complete with drums, face painting, and Mopane worms. A few brave souls in our group decided to embrace the moment and try the worms. While they claimed the worms were not that bad, many in the group remained skeptical. This trip is a wonderful experience for us to view Johannesburg through the lens of a student studying abroad. While there are many exciting things for a student to experience, there are also constant reminders of the poverty and crime in the area. We are struck by the massive amount of barb wire around almost every complex, endless number of homeless people, and areas where people are struggling to get through each day. Our group is reflecting deeply on each of these issues, and it is our hope that through our experience we can return to campus where we can share with students and colleagues both the beauty and potential of the South African people but also their struggle. It is an amazing place and much can be gained from a better understanding of this place and her people. Ann and Andy

1 note

·

View note