Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Beautiful and Damned (1934)

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

You must begin to feel and sense that it is your divine right to be well-cared for no matter what your occupation is or bank balance looks like. You give so much naturally and without thought that to be well-cared for and well-resourced also has to come naturally and without thought, a divine woman’s frequency realized and return back unto her.

You were not made to be constantly exhausted or treated badly. You were made to feel fierce and capable and also soft and tender. Like the finest China, you too were made to be handled with great care and courtesy.

I didn’t just write words for you to read. I wrote a frequency for you to to feel into and permit yourself to live inside of. —India Ame’ye

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

“And even if we never talk again, please remember that I’m forever changed by who you are and what you meant to me.”

— Chasing Amy

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

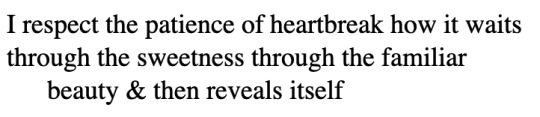

Joy Sullivan, “Before”, Instructions for Traveling West

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

"He is spontaneous, wild like a storm and electric to the touch; divining rod in hand, I seek him out just to feel the lightning."

Moka Lynn, Supercell

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

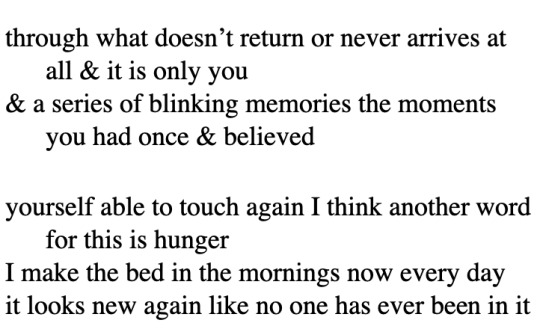

Hanif Abdurraqib, from "There Are More Ways to Show Devotion", You Are Here: Poetry in the Natural World

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Joy Sullivan, "Ghost Heart", Instructions for Traveling West

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Eventually soulmates meet, for they have the same hiding place.”

— Unknown

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

March 16, 1927 Journals of Anais Nin 1923-1927 [volume 3]

496 notes

·

View notes