Text

Please, no more live action remakes

Oh, glorious CGI! We are a slave to your technicolour dreamscapes, your larger-than-life monsters. It seems remarkable to me to rewatch the first Harry Potter film and realise that I am expected to be gripped by terror, watching that magnificent blue troll before me. It looks, in all honesty, a little juvenile. Like a troll doll. This is not the stuff of nightmares. J.K. Rowling, apologies might be necessary. But, as a consolation—it was thoroughly enchanting when I was eleven.

It seems that recently, Hollywood has been afflicted by a particular disease that I have no patience for: the live-action remake. Technology has leapt through the vortex of time, with much more up its sleeve. “Let me at Aladdin!’, it says, screams reverberating down the corridors of nostalgia, ‘I’ll show you a real genie!”

I am here to ask, nicely, for this to stop. We do not desire remakes. We do not wish to revisit the movies that defined the crisp outlines of our childhood, but this time with a hyper-realistic Bengal tiger, tendrils of fur quivering through the Arabian breeze. Give me Jasmine in all her animated glory. Not Naomi Scott, as brilliant as she might be, with her embroidered sky blue two piece.

Look—I know that this might be exhausting. Thinking of a new plot that will enthral both child and adult alike is an ambitious endeavour. What is there to be done that has not been done already? New ground is nebulous. It is difficult. But there is no reason to taint what is already wholly beloved.

James Cameron had to wait ten years for his imagination to calcify into Avatar. And what a joy what was! But he waited. He didn’t make an animation to infatuate us. To lure us into a sure-fire box office hit, all the while pacified with the knowledge that it would all be okay, and the narrative wouldn’t change. We didn’t have to envisage what Jake Sully would look like, because we had Sam Worthington and his prosthetic legs.

We grew up watching Cruella and her luxuriant coat, without the involvement of PETA. We imagined Belle and her Beast, his cartoon embodiment translating just how hideous he was meant to me. The jungle that Mowgli crawled into that was laced with animated serpentine horror. Alice fell through that abyss of illustrated curiosity. Peter Pan soared to that second star to the right, with Hook’s bobbing cartoon ship in his wake. We loved it—we love it still.

Technology is a marvellous thing. The movies of today burst forth with gargantuan dragons, each scale reflecting a different angle of light. Magic is real, it is arcing across our telly screens. But there is nothing, truly nothing, that can replace cartoon Mulan: a warrior running through the snow-encrusted landscape, chest bound and tiny dragon in tow. There is no need to prove yourselves, Disney, because we are already enraptured. Yes, à remake is a done-deal, it is going to make millions. Yes, it is offers you another shot at redeeming yourselves after the white-washing of your first go at Han Dynasty China. But is it worth tarnishing the fond childhood memories of millions? Leave the classics alone. Let them be.

Make new movies with different plotlines. Employ your diverse cast in fresh roles, as unknown characters. Make sequels, if you must (a la The Incredibles, less so Finding Nemo). There is no need to shake the foundation upon which we stand, a foundation built from sentimental tape cassettes of Winnie the Pooh and the Lion King. For Robin Williams will always be the voice to my bubbly caricatured genie.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Long live the banana bread!

It seems that while working from home has triggered the sourdough renaissance, home cooks have also turned to a baked good on the opposite end of the commitment spectrum. It’s squidgy, it fills your kitchen with an aromatic fug, and is the perfect home for those bananas you have left languishing on the kitchen counter. Yes, we are taking about banana bread.

At it’s very basic, banana bread is a quick bread whipped up from terrifically freckled bananas (the more blemished the better), flour, sugar, and a raising agent. Perhaps calling it a bread is generous – for despite its loaf-pan shape, it is undeniably a cake in disguise. I am by no means suggesting a renaming, for parading my chunky slice around as bread grants me the permission to have it for breakfast. Amidst all this pandemonium, I feel like we all deserve a little slice of heaven (read: cake) in the morning.

Banana bread is simply too various in its incarnations – swirled with peanut butter, lavished with chocolate, or punctuated with crushed walnuts. Maybe you prefer yours topped with a crumble to provide a textural counterpoint. Do you make yours with white sugar, leaving it airy and crisp? Or with the sticky saturated brown sort, in order to lend the perfect squidge to your loaf?

I have reduced the banana bread to its very basic. And, win-win, it’s vegan. This is the perfect formula to provide the strongest of foundations for your banana bread creativity. Add chocolate chips! Sesame seeds! Use any sweetener you have on hand! The only limit is your imagination, or more realistically, whatever you manage to find on the desolate shelves at Tesco.

Makes: 1 loaf, 12 slices

3 very ripe and freckled bananas, mashed (about 500g)

2 tbsp oil

2 tbsp peanut butter/tahini/any nut butter/more oil

1 cup sugar (I use an even amount of light brown sugar and white)

1 tsp vanilla

1 tsp baking soda

1/2 tsp salt

2 cups (250g) plain flour

1/4 cup nut of choice OR chocolate chips OR a mix of both—let’s be real

Preheat your oven to 175C and grease and line a loaf tin.

Blitz all the ingredients together except for the flour and nuts/chocolate until smooth, then pour it out into a bowl

Gently fold in the flour and nuts/choc until just combined. Do not overmix this, or you will get a tough banana bread.

Pour it out into the prepared pan, smooth out the top and top it with about 1 tablespoon of rough demerara sugar (the kind you stir into coffee bc you are under some illusion that it is healthier).

Bake for 45-50 minutes, or until a skewer inserted through the centre of it comes out clean and un-tacky. Let it cool for 15 minutes before hoisting it out of the pan and consuming it in its entirety.

If you are a better person than I am and have more leftovers than you know what to do with, you can freeze the slices and microwave each whenever a banana bread craving strikes.

0 notes

Text

Adventures In Sourdough, Part 2: From Starter To Bread

This is part 2 in the sourdough series, for part 1: how to make a starter, click here.

Welcome back, young grasshopper. We meet again and you are now one bubbly, vibrant starter richer. But how to transform this beast into a humble, crackly chunk of sourdough?

Onwards!

There will be a bit of science involved in this, and feel free to skip ahead if you aren’t all too fussed about the mechanics of sourdough. But if you truly do understand why and how this bread is made, you will be better equipped to remedy any problems as they arise, and adapt it to suit your kitchen environment.

The starter

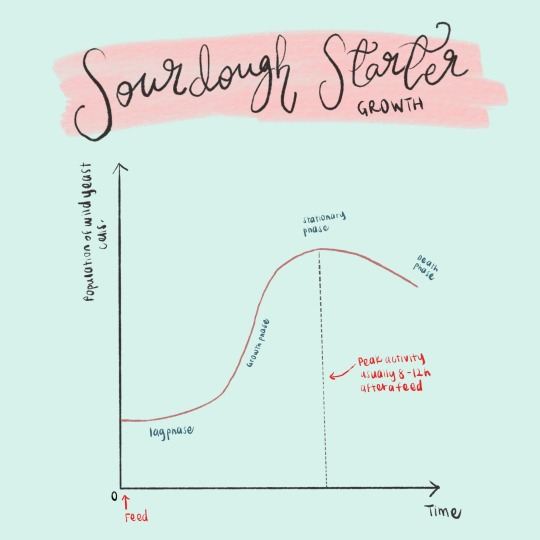

Each starter will have its own personality, its own sass. Over the past few days, you might have grown more accustomed to your starter’s behaviour. How soon after a feed does the starter climb up to the highest point in the jar?

In the cool of England, this usually takes anywhere between 8-12 hours, but if your kitchen or the weather is running warmer or cooler, it might take a shorter or longer period, respectively. A good way to figure out how much your starter has truly grown is to place a rubber band around the jar, or a bit of tape, to mark the level of your starter right after you have replenished it with a fresh feed. Take note of how long it takes for the level to reach a point furthest from the mark before sinking in on itself.

This article will work off the assumption that it takes about 12 hours to reach peak starter activity. If your starter deviates from this, just plan to feed your starter earlier than 9pm if it takes longer to grow, or later than 9pm if it grows rather rapidly. For example, if you notice the starter takes 14 hours to reach its largest size, prep to feed it at 7 p.m. If in only takes 10 hours, feed it at 11p.m.

Loaf Hydration

Sourdough varies in its hydration level. This is calculated as the ratio of water to the flour in a recipe. We will be making a 70% hydration loaf—so, 700g of water for every kg of flour—which is a great one for beginners as the dough is compliant and not too tacky. In sourdough, there is a trade-off between how easy a dough is to work, and how airy and loose its crumb will be.

You know those great artisanal loaves you get at bakeries, that harbour voluminous air bubbles which leak the molten butter you spread over it? Those loaves have a high hydration value. So, while they are terrifically pretty and a joy to eat, they can be a nightmare to work with if are just learning the ropes. As you make more loaves, you can slowly up the volume of water in this recipe to get closer to a 75-80% hydration level, in your quest for something to cure your Gail’s withdrawal.

Let’s get Cracking

I have drawn up a little checklist which you can print off, or refer to on your phone, as you work through the steps. The checklist has 2 columns so you can use it for two rounds of bread making, if you catch the sourdough bug. The full recipe, with all the measurements, can be found at the end of this article.

Day 1: Prepare your starter

Now that your starter is thriving, you need to give it a feed so that it is ripest when you are ready to make bread. As mentioned above, most starters are ready 8-12 hours after a feed, so logic follows that if you feed it at 9 p.m. on day one, it should be ready to party at 9 a.m. on day two. You may have to slide either way of 9 p.m. on the first day if your starter takes much longer or shorter to reach its peak.

To prepare your starter, discard all but a tablespoon or so of it, and top it up with 50g of flour, and 50g of purified water. Stir well, and rest in a warm place with a cover lightly on top of it.

When you have returned to it the following day, it will be frothy and alive.

A good way to check if your starter is ready is to drop a spoonful of it into a bowl of water. If the starter floats, all systems go. If it sinks, however, you might have to wait a few more hours for it to float, or feed it again if you suspect you have waited too long and missed its peak.,

Day 2:

Wake up fresh and early the next day. With the promise of sourdough coursing through your veins, it shouldn’t be too hard.

Autolyse

Many sourdough recipes call for a process called the autolyse, where all the flour and water is mixed into a shaggy dough, and left unattended for 20 minutes to a few hours. This allows the gluten in the flour to develop and for the starch in it to break down. The result? Better texture, flavour, and an all-round happier ball of dough. The starter and salt and left out at this stage, as they can retard this process.

This might seem like a faff and a lot of time wasted, but it works wonders in relaxing the dough, giving you a smoother and more elastic result. So, don’t skip it. It pretty much involves only a few minutes of active stirring before being left to its own devices.

To prepare the autolyse, mix all 500g of flour with 350g of water in a large bowl, and stir it until it comes together and no more dry patches of flour remain. Cover, and let it sit for an hour before you return to it.

Mix in Starter and Salt.

Weigh out 75g of starter (this should leave you with about 25g remaining, just continue feeding this extra bit as normal for future loaves), and 10g of salt. Pour these evenly across the surface of the autolysed dough, then use your hands to pick up the dough from the edge of the bowl, and pull it over and across to envelop the yeast and salt. Do this from different edges until the starter and salt have been roughly incorporated.

The dough at this stage will be uneven, with areas containing your starter/salt and others of pure dough, but don’t worry. As we continue to fold across the next few hours, the starter and salt will disperse themselves throughout the dough.

Cover this, and let it rest for another hour.

Four rounds of folding

After an hour, you are ready to fold! The aim of this part is to build tension with the gluten in the dough, so that the air that the yeast creates can get trapped and cause the dough to balloon out – the makings of a light and airy loaf of bread. I usually do this in 4 rounds of folding, in this manner:

First fold, 30-minute rest >

Second fold, 30-minute rest >

Third fold, 50-minute rest >

Final fold, 1h 30min rest (this last part is known as the bulk fermentation, and is where your loaf grows the most)

If you are in possession of a stand mixer, you might be tempted to stick it with a bread hook and knead away – please, don’t. The yeast in a sourdough is much weaker, slower. Any harsh kneading will eliminate the pockets of air you are trying so hard to build up.

To fold the dough, wet your hands to prevent sticking, and pick it up on the edge furthest from you, pull it up to stretch out the dough, then fold it over to the opposite side. Turn the bowl 45 degrees clockwise and repeat this. Do this four times in total. Here is a video of the technique. Be gentle as you fold, and try not to deflate it too much.

Once you have completed your final fold, you will notice the dough is looking much puffier. Leave it to rest for one and a half hours following the fourth fold to bulk ferment, where it will grow even more and its twangy flavour can intensify.

Shape the dough

Now we are ready to shape! Gently coax the dough out of the bowl and onto a well-floured countertop. A bench scraper (also known as a dough scraper) is a fantastic tool that can help make this part of the process a doddle, but if you don’t have one, any piece of flat rectangular plastic or metal can work; failing that, the largest, thinnest spatula you have.

Flour the top of your dough if you find it getting tacky, then run your bench scraper into the bottom of the dough to tuck its edges beneath it and turn it into a round, taunt lump of dough.

As always, it is much easier to watch than try to picture, so here is a handy dandy video using a bench scraper.

And here is one if you don’t have a scraper at your disposal, and need to use your hands.

The aim of this stage, again, is to build tension across the upper surface, so try to get it as tight as you can manage. Once you are happy, overturn your bowl over the dough to cover it, and left it rest for 30 minutes.

Proofing Basket

There are special proofing vessels—known as a banneton—meant to contain your loaf as it proofs, holding it in shape and imparting the striations of flour that are characteristic of a sourdough bread. They can be round or oval, and have a fabric lining which comes into contact with the proofing dough.

These are pretty cheap to order off Amazon, but I before I got one for myself, I just used a deep 8-inch bowl, lined it with a lint free tea towel, and generously dusted the inside of the towel (that will be kissing your dough as it rests) with a mixture of 50% flour and 50% rice flour. This coats the towel and prevents your dough from sticking to it.

Rice flour has great non-stick qualities, but if you don’t have any, using 100% plain flour works just as well. Just don’t be stingy – you can always brush off excess flour before the bake but saving a loaf that has adhered itself to the towel is far trickier.

Once you have floured your tea towel or banneton, shape the dough into an oval (if you have an oval banneton) or a circle. Tuck the edges into a seam at the bottom and pinch them together to form a seal, and a taut top.

Plop this globe of dough into the prepared and floured proofing vessel, with the seam side facing up towards you. Add more flour on the top of the dough to prevent sticking when it rises, and let it rest for another 30 minutes on the countertop.

This is where things deviate. Sourdough is a chose-you-own-adventure kind of situation. If you have time on your hands and want a better flavour, I highly recommend you place this in the refrigerator overnight, covered loosely in a plastic bag. Bake it the next morning: just in time for breakfast! This version also has the advantage of holding its shape better in the oven, as it flattens out less. Just don’t leave it for more than 24 hours or it runs the risk of becoming overproofed.

If you are impatient, you can leave this to rest a further 3-4 hours on the countertop at room temperature, until it is plump. The flavours don’t mature as much this way, but it is speedier.

TO tell when your dough is ready, give it a firm poke. If you make an indent that takes a few seconds to gently and gradually spring back, it’s ready. If you don’t make an indent at all, it is underproofed and needs more time. However, if it makes a dent that doesn’t spring back at all, it has been overproofed. This is almost impossible to rescue, so check often.

However way you chose to do it, baking it will be the same.

Baking

A hot oven is critical in sourdough making. Traditionally, steam ovens are used to make sourdough, which is why it has such a glorious, chewy crust. Home-bakers prefer to achieve this with a Dutch oven, which is made of cast iron and can withstand the high heat, but more importantly traps moisture around the loaf.

If you (or, more likely, your parents) have a Dutch oven, make sure it is oven safe up to 250C. These things cost a pretty penny, so I have found a way to get around this. A good method to introduce steam is to pour a cup of water into a preheated tray at the bottom of the oven. The following instructions are for using a Dutch oven, but will include instructions in italics for those of us not yet acquainted with the joys of being a Le Creuset owner.

Preheat the oven to 250C, as high as it can go, with the Dutch oven inside of it, for 30 minutes. Preheat the oven to 250C and preheat 2 trays, one in the middle of the oven, and a smaller, deeper one on a bottom rack.

When the oven is hot and ready, remove your dough from the fridge, overturn it onto a piece of parchment and gently pry away the tea towel. Use a pastry brush or your fingers to dust off any excess flour, then use a sharp knife, or a baker’s Lame (essentially a razor blade skewered through a chopstick) to score a pattern on it to give the steam an escape route. When scoring, do it deftly with a firm, decisive stroke. You want to cut through the top-most layer of the dough surface, but only superficially. Here is a fun little chart of some of my favourite bread scoring patterns, but you are completely allowed to let your imagination run wild. I wouldn’t mind in the slightest.

Open the oven, uncover the hot dutch oven and lower the dough on the parchment (use the parchment as a hammock) into the preheated dutch oven. Use the best oven gloves you have for this step as the Dutch oven is wicked hot. Cover, and bake for 20 minutes. Open the oven and lower the scored dough with the parchment onto the top preheated tray. Wear oven gloves, and slowly pour a cup of water into the lower tray, and it will sizzle and splutter. Close the door quickly to trap in the steam, and bake for 20 minutes.

After 20 minutes, lower the oven to 230C, and remove the cover on your Dutch oven (wearing gloves!). Continue to bake for 20 minutes to encourage the upper crust to bronze up nicely. After 20 minutes, wear sturdy oven gloves and remove the tray of water. Since this loaf has not been covered, it should already be browning nicely. You might have to place a sheet of foil on top of it now, or in 10 minutes or so, to prevent it from charring too much – so keep an eye on it. Lower the heat to 230C and continue to bake for 20 minutes.

When the time is up, remove the loaf from the oven and cool it on a wire rack. Give it a little tap on the bottom to check if it is cooked—it should sound hollow. Summon all the willpower you have left to avoid slicing it open while it is searing hot. I know, it’s awfully tempting. You want to see if your efforts have paid off, you need to inspect that crumb. It goes against the laws of human nature to eschew fresh, warm bread. But, young grasshopper, wait. Slicing a loaf open before it has rested can leave it gluey and gummy, and you are so close to the finish line. I like to rest it for an absolute minimum of 40 minutes, but up to 2 hours is ideal. So, set a timer and try to distract yourself as best you can.

Once that timer has ding-ed, and your loaf is cool to the touch, use a sharp bread knife to slice the loaf into thick wedges. You might be dreaming of piling it high with an avalanche of mashed avocado and flaky salt, but I think it is skyscrapingly tasty just as is – this is as close as it gets to enduring bliss.

Now that you’re are a sourdough aficionado, and in possession of your very own sourdough starter – how do you keep it alive so that it can supply you with crusty loaves for years to come? Stay tuned for part 3 where we will chat about how to keep your starter thriving, and how to store it if you need to take a break from all this heavy-duty bread making.

Here is a condensed recipe:

The fool-proof sourdough loaf

I use a mix of bread, plain, and whole-wheat flour here, but you can alter it according to whatever you have on hand. I recommend always keeping about half of it bread flour, due to its high gluten content, but otherwise stick to 500g of flour all up.

Starter:

1 tablespoon active starter

50g plain flour

50g purified water

Loaf:

250g bread flour

200g plain flour

50g whole wheat flour

80g of the starter (reserve the rest to feed to keep your starter going)

10g salt

To flour the banneton or tea towel:

¼ cup plain flour

¼ cup rice flour

The night before, mix all the ingredients for the starter in a clean bowl, and leave it somewhere warm to grow.

The next morning, about 10-12 hours after feeding the starter, place the flours and water in a large bowl. Stir to combine, and then cover and let rest for 1 hour.

Measure our 80g of starter from the jar you have left fermenting overnight, and add it to the large bowl with the salt. Fold it in to incorporate and leave to rest for another hour.

For the first fold, fold the dough at 45 degree angles, building up tension on the underside. Rest 30 min

For the second fold, fold as in the previous step and rest 30 minutes

The dough should be looking plump now, gently fold it as normal, but this time let it rest for 50 minutes.

Fold the dough for the fourth and final time, then let it rest for 1h 30min-2h until it is plump and supple.

Overturn the dough onto a floured countertop, and use a bench scraper to gently coax it into a smooth ball. Cover and rest for 30 minutes.

Shape the dough into an oval or round depending on the shape of your proofing vessel. Dust the inside of the vessel or towel well with the plain and rice flour. Place the shaped loaf into the proofing vessel, seam side facing up. Rest for 30 min.

You can either place this in the fridge overnight (a max of 24 hours), or leave it to proof further on the countertop for 3-4 hours.

Use the poke test to determine when the loaf is ready to bake. A finger should leave an indentation that gradually springs back.

When the loaf is ready, preheat the oven with a Dutch oven within it to 250C. If you do not have a Dutch oven, you can preheat a tray at the bottom rack in which you need to pour a cup of water when you place in your loaf.

Unmould your dough and brush off excess flour, score with a knife or Lame, and place in the preheated Dutch oven. If you are using a tray of water to introduce steam, pour it in now. Bake for 20 minutes

After 20 minutes, uncover the Dutch oven, lower to 230C, and bake another 20 minutes. If you did not use a Dutch oven, you might need to cover the loaf loosely with some foil to prevent burning.

Remove the bread and cool on a wire rack for 40 minutes to an hour before slicing open.

0 notes

Text

Adventures in Sourdough: The Starter

A renaissance is afoot. Social media is inundated with pictures of crusty loaves boasting burnished crackly tops, with cross-sections flaunting that well-sought-after ‘open crumb’. The millennial vice that is avocado toast has been given a makeover—avocados now sit on top of homemade, salt-of-the-earth-type fermented bread. In case you’ve been living under a rock, here is the TLDR: sourdough is the new black.

With seemingly nothing worthwhile to occupy our time with, humanity has turned to old-school bread making as the antidote to our collective boredom. Now that supermarket shelves are devoid of any form of active dry yeast, what better time to try your hand at making bread with the wild sort?

Sourdough might sound intimidating, slightly archaic even. If social media has not already won you over, I am here to make a case for it. There is a certain kind of magic that is found in building a rustic loaf out of nothing but flour, water, and time. Since we appear to have ample amounts of time on our hands (less true for flour, I’ll give you that), invest a fraction of it in some wild fermentation. You’re in for a wild time.

Over the next few weeks, we are going to get into the nitty-gritty of all things sourdough. But with all great adventures, we must begin with a disclaimer: you will develop an emotional attachment to your starter; other members of your household might resent you for keeping a jar of twangy, bubbly dough on the kitchen countertop; and it is going to take time. Sourdough involves saint-like volumes of patience, but I’ll make you a promise: it will be worth it. After all, Rome wasn’t built in a day.

Sourdough is a living thing. If you have ever made bread, you might have watched in rapturous wonder as your solid lump of dough balloons out into a pillowy mound. Modern-day bread-making often relies on those sachets of dried yeast (RIP) to inoculate your dough with the living organism that gives your bread that rise. But before yeast was domesticated, bakers relied on capturing wild yeast to bring life into the loaf.

In order to harness the power of wild yeast and begin your sourdough journey, you will need to make a starter. This is simply a mixture of flour and water, left to languish somewhere warm, to let the wild yeast in the flour do its thing. The starter requires daily feeding, but it is an otherwise agreeable pet. It will take about five to seven days to get a truly bubbly, vibrant starter. And while that might seem like forever in our age of instant gratification, a starter is a gift that keeps on giving. Keep your starter happy and it might even outlive you. You could be cultivating your next family heirloom, and I will take the makings of a good loaf of bread over an old rusty bit of jewellery, any day.

Building blocks of a starter

The formula to a starter couldn’t be simpler: an equal weight of both flour and water. You can use any type of flour you have on hand, I tend to stick with the plain sort. Wild yeast, ever the hippies of the bread scene, prefer whole wheat. So, if you are looking to kick-start your fermentation, try a 50-50 mix of plain and whole wheat.

But yeast can be pickier when it comes to water. The chlorine in tap water can stunt its growth, or even kill it. Just use bottled or filtered water, and you’re golden. It is time to whip out that Brita filter.

You will need to find a good home for your starter: a clean jar that allows enough room for growth, and somewhere warm. I am writing this in the suffocating humidity of Singapore, so finding somewhere warm was a doddle for me. But if you are reading this from somewhere cooler (lucky you), I have always found that storing my starter on top of my fridge, where the surface of it feels the warmest, is enough for my starter to get going. But if you are partial to getting snuggly under a blanket in front of Netflix, I am sure the starter will welcome a cuddle.

Beginning a starter

Weigh out 50g of flour (25g each of plain and whole-wheat is great for getting a starter going) and 50g of filtered water at room temperature. Pour them out into your clean jar, and give it a stir until all the lumps disappear and a thick, shaggy paste forms. Loosely cover it with the lid. Do not screw it on, or the lid might ping off rather dramatically as your yeast lets out air. Leave it in a warm place for 24 hours.

After a day, you might notice little bubbles studded across the starter. The paste itself will have loosened, and might have even developed a thin striation of clear liquid. This liquid is the hooch that the yeast has produced, and yes, it is slightly alcoholic. But I trust that the alcohol-supply situation has not gotten so dire as to necessitate you drinking this. You can pour this off since hooch is ‘wasted energy’, but I like to keep it in when I stir to add an extra boost to flavour. For those who don’t drink, don’t worry, the final bread you make will not be alcoholic.

So, give it a stir, and pour out half of it. You could just chuck it down the bin, but in this time of making the most of what we’ve got, I recommend you find something to do with it. The internet is saturated with weird and wonderful ideas on how you can employ this excess starter, and we will discuss some of my favourite uses for this bit of spare dough in a later instalment.

Feed the starter again with 50g each of water and flour, stir, and let it rest. On the third day, you will likely see a lot more bubbles, and a whiff of it might invoke memories of yogurt or some twangy pickle. You’re on the way to flavour city. All the same, stir well, discard half, and refuel it with 50g of flour and water.

Feed, sleep, repeat. Keep this going every day and by the fifth to seventh day, your starter will be pockmarked with huge bubbles, nearly doubling in size with each feed. It is flourishing! It is thriving! It might take you slightly longer to get to this stage if your kitchen runs a little cooler, but with regular feeds and a warm enough environment, your starter will slowly come to life.

When your starter is regularly doubling in size about 12 hours after each feed, and is frothy and funky, it is ready for bread-making. Watch this space for part two, where we will discuss how to transform your starter into a truly magnificent sourdough.

Kick-starting a starter

For the slapdash cook, you have not been forgotten. If you feel you do not possess the diligence or patience required of a starter, there is a fast-track. I am not all too sure what sourdough purist will think so if you are a traditionalist: avert your eyes!

Wild yeast can also be found on the surface of fruit, fresh or dried. I have recently been made my starter out of about a quarter cup of raisins, left to steep in 50g of water. Give it a swirl, and you will notice the water turning cloudy. This, my friends, is the yeast. Scoop out the raisins (and chuck them into your morning porridge), and add in the 50g of flour. Continue feeding the starter as instructed, but you will find that the starter comes alive much sooner.

I haven’t tried this with other fruit, but I trust that it will yield similar results.

Name your starter

An unspoken rule of sourdough club is to name your starter. An unnamed starter feels neglected, and might not reward you as generously. This is a scientific fact.

You can go for the literal (‘Yeasty’, or ‘Sour Mama’), the endearing (‘Shirley’ or ‘Bartholomew’), or the plain ol’ weird and whacky. For me, it was a toss-up between Avril Levain and Clint Yeastwood. My affection for a good pun knows no bounds.

Go forth and have a go at rearing your very own sourdough starter. If you’re feeling terrifically lonely in social isolation, there is hope! A DMC with Avril Levain has always left me with a warm, fuzzy feeling. Check back in a week for the low down on how to work more sourdough alchemy.

Image Credit: The Pizza Bike, Flickr Creative Commons

0 notes

Text

Embrace Your Freezer

I think you have heard this far too many times – stranger times are afoot. Stockpiling is a particular point of aggression for me, because there is simply no point in buying far more than you need. If supply is an issue, the answer lies in simply utilising the best appliance at your disposal. Yes, I am talking about your freezer.

There is a multitude of food that behaves rather well if you plunge it into the icy-cold depths of your freezer. But, as always, the question of food safety arises. Here is a crash-course into what freezes well, how to fight the devil that is freezer-burn, and what is a freezer-flop and must be avoided at all costs.

Bread I place this at the top of my list simply because I believe that far too many people have been chucking their Hovis slices into the compost when the slightest bloom of mould appears. Bread is the king of freezer foods. If you buy your bread pre-sliced, you can chuck whatever you believe you cannot finish by the sell-by date into the freezer. If you are a better person than I am, and get those crusty loaves à la Gail’s, make sure to slice them into neat pieces before freezing. Whenever the need for toast arises, no thawing is necessary. Pop it straight into your toaster. You can’t imagine a thing better since frozen bread.

Fruit Sure, you can buy pre-frozen fruit, and there is nothing wrong in that. But if you think you have far more than you need fresh, you can freeze whatever excess you have. Most fruit freezes remarkably well. And while in some cases (I am looking at you, citrus) the texture does deteriorate, if you are using it for baking/smoothies/juicing – no one would be none the wiser. A point of note: pitted fruit does best if you remove their stones before the freeze – trying to pry it out with a knife sub-thaw is not much fun. Avoid the peach equivalent to the millennial avocado injury. Citrus, forgiving my previous dig, is OK if you are using the pulp for a recipe or smoothie – but the zest reigns supreme. Zesting a frozen wedge of citrus fruit is easy peasy. And if you happen to need the flesh of citrus without the skin, just freeze it for whenever you may want to make a casserole calling for that tablespoon of orange zest.

Herbs We are all culprit to buying a pouch of rosemary when a recipe demands it, and leaving the remainder languishing in the produce drawer. If you have far too many fresh herbs than you know what to do with, freeze them (spoiler alert). Herbs are best if frozen in some kind of fat, so what I do is portion them out in an ice-cube tray, a teaspoon per well, and top each up with a glug of olive oil. If your next pasta sauce demands 2 teaspoons of fresh rosemary – pop out two cubes straight from the tray and toss them into your pan.

Soups and stocks I am a fan of the Kallo stock cube. But there have been times (i.e. mid-risotto making) when I have had far too much ready than I need. Instead of chucking it away, freeze them in portions (I like to go for a cup per container), so you know exactly how much to thaw out the next time you need it.

Leftovers I wrote an entire article about leftovers, and it seems particularly prescient to not let whatever you have spare to go to waste. Stews and curries fare particularly well from being frozen – just make sure you portion them according to how much you need for a meal.

Vegetables The list of vegetables that do well from freezing is far longer than those that do not. Onions, garlic, hard veg (squash, root veg, peppers)… Spinach and kale, while of the leafier variety, do well if you plan to deploy them later in a cooked dish and not in a salad. Skin your tomatoes before freezing – by slitting an X at their base, boiling them for 2-3 minutes, then immediately plunging them into a bath of ice-cold water. Their skin will start to shrink back – so peel off whatever remains with languorous ease and pop them into a freezer bag or Tupperware. While most root vegetables fare well, but potatoes do not. Only waxy potatoes do relatively OK, but I advise this only if you want to use them in some sort of stock, as their texture does change. Just parboil them before freezing. As a general rule of thumb – veg with a high water content either should not be frozen (i.e. iceberg) or needs some treatment. Hardier veg is much more resilient.

Tofu Even if food shortage is not an issue, I am a proponent for freezing your tofu.

Baked Goods Do you know how some people have eyes much bigger than their stomachs? I bake much bigger than my stomach. Most baked goods can be frozen. Banana bread, cinnamon rolls, cookie dough – it’s all good. Just make sure to portion them accordingly for future ease. To bring them back to their former glory – a whirl in the microwave is all you need.

Butter FREEZE YOUR BUTTER. I use non-dairy butter, but the rule withstands. And, hey, if you happen to be the sort that makes your own shortcrust – pre-frozen butter is a godsend.

Yoghurt and milk Yes, I am aware that some dairy comes with a warning emblazoned on the side of it – DO NOT FREEZE. But if your intention is to use your dairy in a dish, frozen shouldn’t be a problem. Freezing yoghurt or milk (or non-dairy equivalents) changes the texture of it – no longer silky and velvet but rather (urgh!) lumpy. This resolves itself if you throw it into a biryani or a pasta sauce, but not have any intention of consuming it as you would fresh. Just try you freeze whatever you do not think you can finish as soon as you can – anything a day or so near its sell-by date is risky business.

Eggs Don’t freeze your eggs in their shells. Crack them open, beat them and portion them in containers labelled with how many eggs lie within them.

Cheese Hard cheese freezes well, soft cheese less so. If you find a bit of mould growing on your wedge of parmesan, it is completely fine (and safe!) to cut it off with a generous margin, and freeze whatever remains. Soft cheese should not be frozen at all costs – and if you find yourself in the unfortunate circumstance of finding a bit of mould on your mozzarella. Chuck it. It isn’t worth any risk.

Flours Wheat, rye, spelt, buckwheat, oat… they are the superstar of the freezer. Whenever you need any for a bit of baking, scoop it out and proceed as you would normally.

Nuts and seeds I grew up in a hot climate, so all of our nuts and seeds claimed residence in our fridge or freezer. Nuts and seeds possess a fat that can, at times, go rancid in warmer temperatures. This poses less of a problem if you buy small bags of the stuff that they sell at Tesco. But, if you are a bulk-buy fiend, pop whatever you think you will not employ in the next few months in the freezer. It will save you a lot of money, and heartache.

Cooked rice, grains and pasta Yes, you can freeze these. Rice can be tricky, but be sure to cool whatever excess you have ASAP and pop it into the freezer once it is at room temperature. Pasta can be frozen, but please, only if it is just shy of al-dente. You will need to plunge it onto some hot water to revive it, and if it is already slightly over, you will have a soggy, gloppy mess.

Meat Freezing meat can appear to be a risky endeavour but if you follow a few rules, you’re golden. Freeze it as soon as possible, portioned as you would need per meal. When freezing meat, air is the enemy. Wrap each as much as you can in plastic wrap (or leave it in the vacuum pack it came in) and a further insurance of foil or Tupperware to discourage freezer burn. When thawing (which will be discussed below) – you can either leave it in the refrigerator for a day (smaller portions) or more, or in a tub of slightly-cold water. DO NOT leave it on the countertop, DO NOT microwave it. The 3-month rule applies here for maximum quality, and while a few months shy of that should be okay, the quality of it does deteriorate significantly.

Safe-Freezing Tips

You are now a freezing aficionado. But here are a few final tips about the longevity of frozen food, and just some general freezer-related housekeeping.

How long is it good for? This depends on the food. And while there are a whole list of websites and charts demanding you follow a strict schedule, if you have frozen the food as close to fresh as you can, a lot of it will be OK. But, for the wary, here is a good guide.

How should I freeze? A rule of freezing – minimise air contact. With meat this is crucial, but otherwise, try to use freezer-safe bags or tubs with airtight lids. Label EVERYTHING – with its contents, portions, and date of cooking/freezing. Always try to freeze according to your regular portion size so you can thaw exactly the amount you need.

What should I use to freeze my food? You can buy freezer bags, and containers – but avoid freezing any glass or metal. Glass is particularly tricky as it can shatter (yes, even the freezer-safe ones). Especially if you put anything slightly liquid inside, as water can expand and create cracks your glass container.

How do I thaw my frozen food? You have a few options. You can thaw it in the refrigerator, which is the safest, but also takes a fair amount of time. To speed things up, you can leave it in a bowl of cold water on your countertop, or in the microwave on the defrost setting. Meat, however, should never be let near the microwave in the effort of food safety.

How do I prevent freezer burn? This happens over a period of long freezing, when food loses its water molecules and they rise to the surface and crystallise as ice. Small ice crystals do not pose much of a problem, as they melt fairly quickly. But once larger crystals form, this usually indicates the deterioration of whatever you have had frozen. It is usually still alright to eat this (with the exception of meat and dairy products), but just be prepared for it to be a little subtracted in its original quality.

Image Credit: Theo Crazzolara, Flickr Creative Commons

0 notes

Text

Self-isolation cocktails

Amidst all of the current chaos, my sister agonised over the question: "What will we drink?". The internet is saturated with articles telling you to have FaceTime wine nights or to transpose your cocktail hour into the virtual world. I admit that many of my undergrad years were spent mixing house-brand vodka with Robinson's squash, but in an effort to distract myself from our current atmosphere of anxiety, I am hungry for a little more sophistication. Here are five quasi-fancy cocktails you can probably whip up with the current contents of your pantry. And if stirring Nesquik into a quaran-tini might seem a bridge too far for you - what better way to fill your isolation days than with a bit of mixology experimentation?

Art by: Sasha Gill

0 notes

Text

Eating In The Time Of The Coronavirus

It’s 2020, and humanity has become unmoored. Multiple countries have declared a state of emergency. Country borders are closing. Cities are on lockdown: shops are shuttered, rush-hour traffic is a thing of the past, supermarkets shelves lie desolate. Welcome to life in the time of the coronavirus outbreak. Here, pandemonium reigns, for there is nothing that we humans fear more than uncertainty.

Even in times of crisis, we must eat. But now that too has become tricky. Social isolation is a challenging feat in itself. But how do you feed yourself when you are housebound? How do you whip up even the most basic pasta, when shelves in the shops remain bare?

Here I offer you a small consolation in the form of some good news. You are not going to starve, and you do not need to kick into panic-buy-mode (easier said than done, I am well aware). Here are some ways in which you can support yourself, the community, and independent businesses during these unsettling times.

Support Small Businesses

The pandemic is causing major repercussions for small businesses and is likely to cause numerous business fatalities. Xenophobia has reared its ugly head, with Chinese-run businesses being particularly badly hit by plummeting sales. Small business owners are faced with the ultimate dilemma – risk the safety of their staff, or close their doors and risk never being able to open them again. Even those who are trying to ride it out have seen their clientele dwindle down to a trickle.

While the government has advised against going out to cafes and bars, there is still some that can be done to help those in a vulnerable financial position. Many locally-run cafes and restaurants still offer take-out, and Deliveroo has even introduced a contact-free delivery option. Spending money on a takeaway, if you can afford it, can help keep these businesses afloat.

This does raise an ethical question regarding the safety of delivery drivers. They are the ones most at risk since they come into contact with multiple people throughout their shift, and often do not have the luxury of paid time off work or insurance against unemployment. While there is no perfect solution to this, you can always try to be as considerate as possible – chose the contact-free option when available (or call ahead to ask if this is an option), and –please—tip your rider. They are putting themselves at a huge personal risk to provide you with a service. Be careful, be compassionate.

If ordering a delivery is not your jam, there are still ways you can show your support for small businesses. Get a gift card to use at a later date, buy store merchandise (those T-shirts from the Missing Bean are sounding pretty fabulous), get supplies like coffee beans from cafes, or homemade jam from bakeries. Failing that, you can go through a more direct route and donate to crowdfunding pages specifically dedicated to preventing these companies from being crushed beneath the enormous weight of the pandemic.

Admittedly, none of this addresses the systemic issue at hand, that there is little to no support for entrepreneurs and workers who will be tremendously affected by the changing social climate. It isn’t a perfect world, so please be considerate to delivery and service staff – they are trying their best, they are tired, they are worried.

Support the community

If there is one thing I urge you to take away from this article, it is this – panic-buying serves no one. You are left with more than you could possibly need, service staff are weary and exhausted from constantly restocking shelves, and the most vulnerable members of society (who need non-perishables more than we do) are all too often left without. In an effort to counter this, many shops are introducing a protected shopping time for the elderly or more vulnerable. It’s hard to imagine how things have escalated quite so quickly.

You do not need five boxes of penne pasta. If you truly do require a 24-roll pack of loo roll for the week, you should see a doctor for reasons entirely unrelated to COVID-19. This trend of panic-buying is placing an exorbitant strain on supermarket staff, and causing even more people to stockpile as a knee-jerk reaction to seeing empty shelves.

If you are fortunate enough to have grabbed more loo roll or dried goods than you realistically need, donate some of it to people who may need it more than you do. If you are aware of a neighbour or friend who is unable to leave the house easily (due to age, being in quarantine or otherwise ill health), offer to run some essential errands for them. Pick them up some food from the stores, offer to pop into Boots for their prescriptions, or simply give them a ring every now and then to see how they are getting on.

It is especially in times like this when the natural feeder in me bursts forth. I show my love for people by cooking for them, and what better time to offer comfort in the form of a large casserole dish of gooey macaroni than now? Is offering to cook for a neighbour or friend ultimately going to cause more harm than good?

According to the Centres for Disease Control, there is no evidence that the virus can be transmitted via food. The virus itself is heat-sensitive – so as long as you are practising good hygiene, and heating up food to the appropriate temperatures, the risk should be minimal. Salads and sandwiches, for this reason, are a little riskier. The virus has been shown to be able to survive on surfaces for up to 24 hours, so keep everything—hands, countertops, bowls, produce—as clean as possible. Any leftovers should be covered and refrigerated swiftly.

The standard rules apply for the suggestions made here, please make sure that you are feeling well enough in yourself to do this for other people.

Support yourself

Social isolation is not peachy. It is mind-numbingly dull, you run out of ways to occupy yourself, and there is a limit to how many Netflix shows you can saturate your day with (or is there?). I am of the belief that there is nothing that can truly unite people in times of anguish than food. And when physical proximity is impossible, technology can still swoop in to our rescue.

Make a Whatsapp or FaceTime group with your pals, and from a cooking club. Swap recipes, cooking tips, ways to embellish your third day of leftovers. Or, if cooking isn’t your thing, I have discovered that wine is truly one of the best accompaniments to a group video call. It is fancy, it’s social, and you can do it all in your jimjams.

If you prefer cooking solo, perhaps now would be the perfect time to pick up a culinary hobby that would otherwise command quite a lot of your attention. All those months I have spent putting off taking my sourdough starter out of hibernation were not in vain – for now, I have ample opportunity to breathe new life into Shirley (that’s the name of my starter, which is totally not weird, at all). If the prospect of making a ‘mother dough’ sounds like the stuff of nightmares, you can start elsewhere. Make jam! Make pickles! Make Kombucha! Sharpen your knife skills! Learn better puns! The only limit is your imagination… and what social isolation can afford you.

Spending all day indoors can make even the most secure person feel unhinged, so if you are someone who already feels extreme anxiety around our current situation, please, take care of yourself. Make sure you have friends or family members to support you. Self-care comes in many different forms, but it is important for you to find something that eases your mind, even if it is only fleetingly. I write food articles, so naturally, my form of self-care involves quite a lot of time in the kitchen. If you, like me, are fighting an almost irresistible urge to bake fifteen different cookie recipes to decide which reigns supreme, watch this space – we will be offering you cooking projects to fill your days with. Stay safe and stay snug, as we wait this madness out together, even if we are apart.

Photo Source: Eneas De Troya, Flickr Creative Commons

0 notes

Text

You make miso happy

Miso soup, the quintessential Japanese dish. For the longest time, I had a tub of miso paste tucked neatly away in the corner of my fridge. I bought it at the height of my miso soup passion but it was now left neglected, with seemingly no other purpose in life. In an effort to find something else to do with it, I discovered that one of life’s greatest wonders lay hidden in the depths of my kitchen. My love affair with miso soup was on its last dregs, but my infatuation with miso paste had only just begun.

Miso paste is a fermented mixture of soy beans and a grain—rice or barley make a frequent appearance—inoculated with Koji, a type of mould. For the keen bean sake lovers: yes, the same Koji used to make the rice wine. This mixture is left to ferment with a healthy dose of salt, for a variable amount of time (more on that later). The mould breaks the beans down as it cultures, into a mixture of amino acids, fatty chains and simple sugars. The resulting concoction is deeply twangy, funky, an absolute umami bomb. And, as I hope I will be able to convince you by the end of this article, the secret ingredient that will bring you to unsurpassable culinary heights.

The colour, aroma, taste and pungency of a miso paste depends on a great number of factors. The conditions the paste is cultured in, for example, or the age of it. Even the geographical region in which it is let to culture plays a role – due to the different strains of bacteria available to lend a hand in the fermentation process

There is, it seems, a dizzying number of miso varieties, with over 1300 different types available, aged from anywhere between a few weeks to several years. But, in an effort to simplify the whole shebang (miso purists, please forgive my crude generalisation) they can be broadly broken down into two categories – sweet (sometimes called ‘light’) and dark miso pastes.

Sweet miso is the baby of the miso world. White miso paste (shiromiso) falls into this category. It is gloriously golden, the lightest of all the miso pastes – due to its higher percentage of grains. It has only had a several months-worth of fermentation, which is a heartbeat in the fermentation scene. The resulting taste is buttery, and mellow – and makes it, for beginners, the gateway drug. Or, for the adventurous, the best miso option in a sweet recipe.

Dark miso (sometimes called red miso, or akamiso), is the brooding older cousin, and more complex. Dark miso ranges in colour, from a dark brown to an almost-black. It has been fermented for a much longer time and contains more soybeans than it does grains. Time has made it deeply salty, earthy and robust. For this reason, it is the perfect ingredient to plop into a stew, or into a meat rub. It evokes memories of marmite, and indeed marmite is no stranger to a stew – providing the umami foundation upon which so much flavour is built. If you avoid soy, fear not! There has been a recent influx of ‘new age’ miso. The hippies of the miso scene, if you will, and they can be made with anything from chickpeas, farro, adzuki beans, buckwheat, rye, millet, to… if the fermentation gurus of the internet are to be trusted… cookie dough. And while I lack the self-control to be in possession of spare cookie dough, I admire the passion for the cause.

Miso paste is a beautiful thing, not only because of its wonderful resonant taste, but also because of its versatility. Miso isn’t just for soup. Miso isn’t just for Japanese cuisine. You can use it in salad dressings, whisk it into marinades or brush it on as a glaze. Make a compound butter with it, and slather it onto thick wedges of toast. Use it in a sauce to bathe your noodles, mash it into silky potatoes. The line doesn’t end there. Desserts do equally well with a bit of the miso treatment. Swap out the salt in a salted caramel for a spoonful of this golden paste. You’re in for a treat.

As a fermented product, miso has a remarkable longevity, lasting almost indefinitely if treated with sufficient care. As a general rule of thumb, sweet miso is best if eaten within a year after opening – their fleeting fermentation period makes them a little less resilient than their darker counterparts. Dark miso, if left in sanitary conditions in the fridge, will practically last you forever. It will, however, darken over time, thanks to the powers of oxidation. But even this process can be hindered if you keep the surface of the paste covered neatly with a piece of baking parchment.

Another perk of being a fermented product: miso is jam-packed full of good bacteria. You know, the reason why yogurt is touted to be good for your gut? These bad boys are all over your miso paste. For this reason, if you are eating miso for its probiotic health benefit, you should avoid plunging it into a boiling stew or whacking it into the oven for a long braise. Instead, stir it into a stew right at the end, or brush it on as a glaze once most of the roasting is done. I admit to using the stuff, not for its ability to help my microbiome, but because it’s really, really tasty. So while I try not to overcook it, there will inevitably be situations where it cannot be avoided (in, say, baking a miso brownie). Taste trumps health benefit.

There is no better proof, than in the pudding, so I will supply you with what I have found is my favourite pudding to pair with miso. If there are any points awarded for a double pun whammy, I truly believe that this qualifies. I hope – no, I implore—you to give miso a second chance. It is not a one-hit wonder. In the words of Wild Cherry – Play that funky music.

Image Credit: Jules, Stone Soup

Miso Caramel Sauce This is a vegan caramel sauce with which you should adorn every manner of desserts – ice cream, chocolate fondants, layer cakes or squidgy blondies. The only limit is your imagination, and – well – your stomach’s capacity. The 40 minutes of cooking time might seem exorbitant for a sauce but once it is in the pan it mostly takes care of itself, just give it a nudge every so often to prevent the bottom from catching on the pan

Ingredients • 1 can full-fat coconut milk (1 ½ cups) • ½ cup white sugar, or brown • 3-4 tsp white miso (start with 3, then add more to taste) • 1/2 tsp vanilla extract

In a heavy-bottomed saucepan, bring the coconut milk and sugar up to a simmer. Lower the heat to low and continue to cook, for about 40 minutes, until halved in volume. Stir it occasionally, perhaps every 10 minutes or so, to prevent it from catching and burning at the bottom of the pan. Once reduced to about ¾ cups, place a small amount of the hot milk mixture into a bowl with the miso paste and vanilla, and stir it to dissolve. Return this to the pan and stir to combine it fully. Remove it from the heat - the mixture will be an appealing light-golden colour, and will thicken up further as it cools. Store it in a clean jar, in the refrigerator, for up to a week.

Image Credit: Sasha Gill

0 notes

Text

I knew you were truffle when you walked in

Truffle – that illustrious diamond of the culinary world. This rare subterranean tuber is not a thing of beauty – soot-black and bulbous. At first glance, it is difficult to imagine how it has attained its reputation as a gastronomic status symbol. But slice into it and you can reveal its appealing cerebral-like variegations, release its pervasive aroma into the air. Everything makes sense now. It is usually sliced, whisper-thin, to crown anything from an eggy Fettucine to a rare, quivering Filet Mignon. Elevating it to unsurpassable heights.

Its aromatic fug has been known to evoke memories of locker rooms and old socks. Why, then, does it taste so good? One can’t help but to become acutely aware of the inadequacy of language. Descriptions of its robust flavour include earthy, nutty, gamey, musky. The ever-sought-after umami. To me, it has an intoxicating olive-like inkiness. But no matter how delicious you find it, the question remains – why are they so darn expensive?

There are, in fact, several different species of truffle (including, and you heard it here first folks, a psychoactive one), although not all are worth eating. Put simply, the good ones are hard to find, they have a short season, and specific weather conditions are required to cultivate an environment for their growth. They are found within the soil, nestled up next to the roots of a great oak or hazelnut tree. They form a symbiotic relationship with these trees – each becoming instrumental to the other’s growth. Oaks give truffles sugars in exchange for extra nutrients and water, and this transaction cements them to each other. But not all oaks and hazelnuts have truffles growing in their shade, and this is why unearthing one proves so challenging.

In the past, female pigs were used to hunt for the elusive fungi. Truffles release pheromones into the air, which sows are so adept at sniffing out. The problem with pigs is that, being pigs, they tend to eat the truffles they discover. Suboptimal. Dogs, while less proficient at truffle hunting and so require intensive training, do not pose this problem. As a plus, they are also a lot easier than a pig to load in the back of a Jeep before setting out to forage for truffles.

Once a truffle has been dug up from the earth, the clock is on. They have a remarkably short shelf life, only adding to the problem of their steady supply. The evocative aroma of a truffle decreases significantly in the waiting, nearly halving within the first five days. Unlike a cherry tomato still tinged with green, or an unripe peach – time is the enemy. Since the best, the most esteemed truffles come from central Europe, shipping them across the globe wastes valuable time and flavour.

White truffles, the rarest sort, can retail from upwards of USD$3000 per pound. Even their slightly more common counterpart, the black truffle, sells for a head-spinning USD$900 a pound. All this for some fungi. In 2016, the world’s largest truffle weighing in at 4.16 pounds was auctioned off for the whopping price of USD$$61,250. And even then, it was considered a bargain.

Attempts at domesticating truffles have proven iffy. While white truffles have continued to elude cultivation, more success has been found in trying to grow black truffles. Trees first need to inoculated with the truffle fungus, and given high irrigation – but even then, truffles are never guaranteed. The push for their domestication has, in part, to do with their dwindling supply. Climate change has wounded the growth of wild truffles. Truffles do not favour the rising mercury, the plummeting rainfall. The ever-increasing loss of woodland has also affected them. And while up to 80% of the world’s black truffles are now cultivated – this has done little to make up for the lagging supply. Just another victim of global warming and we will be poorer for the loss.

But there is more to this seductive fungus that meets the eye. Hidden behind the glitz and glamour of haute cuisine, belies an underbelly, rich with fraud and deceit. Any lucrative trade is bound to spawn a sprawling black market, and truffles are no different. Counterfeits have become pervasive – the Chinese black truffle, for example, looks identical to the prized Perigord black truffle but barely matches them in flavour. They are often mixed in with the real thing, making it difficult for a restaurant to tell if a truffle delivery is indeed what has been ordered. The only way to definitively prove the difference is with molecular analysis – hardly practical. The practice of some restaurants to lock their best truffles away in a safe, buried in salt and rice, begins to make sense – when you find a good one, you protect it. In the hunt itself, the trade is cutthroat. There are reports of hunters slashing each other’s tyres, some going as far as poisoning each other’s truffle-sniffing canines, in the effort to deter competitors in the hunt. Secrecy is abound, the exact locations of fertile truffle hunting grounds are passed down like family heirlooms – mum’s the word.

If you have ever purchased a bottle of truffle oil, chances are the product you have does not contain a single sliver of truffle. Cheaper truffle products, oils included, tend to contain 2,4-dithiapentane – commonly listed on the ingredient label as ‘truffle aroma’ or ‘flavour’ or ‘essence’. While it is the active ingredient in our prized truffles, the chemical itself is not necessarily extracted from one. In the culinary world, this compound has split opinion. Anthony Bourdain was known for his dispassion for the ingredient, nicknaming truffle oil ‘ketchup of the middle class’. It has been criticised for its one-dimensional flavour, bearing only a passing resemblance to the technicolour of flavour a real truffle provides. Unworthy of being emblazoned with the truffle title.

Whether you adore truffles (or, like me, 2,4-dithiapentane – the only opulence my student budget can afford), or are disgusted with how a mushroom is regarded with such splendour, the fact remains. These little nuggets are a food of transcendent deliciousness. Brewing just below the earth’s surface lies a true testament to nature’s alchemy.

Image Credit: Arnie Papp

0 notes

Text

Leftovers – demystified

Anyone who owns a refrigerator knows that it possesses the strange ability to transform food. The remnants of your Sunday curry night are brightened, your lasagne becomes a delicious, messy gloop. Put simply, it is better the next day. What alchemy is afoot here?

When you cook a dish, whether it is in a saucepan on the hob or in a large baking tray in the oven, reactions happen between the aromatics in a recipe. Think garlic, wedges of onion, beads of cumin, tendrils of cilantro. This produces flavour molecules. But where the real magic happens isn’t what you would expect. As you cool a dish, these reactions continue to take place, simmering just below the surface (pun intended, and apologised for). This produces even more, and sometimes new, flavour molecules.

If you eat a dish right after you have constructed it, more often than not what you taste are the individual flavours – you notice the musky cumin, the herbaceous rosemary. But after leaving it to its own devices, and reheating, it is harder to distinguish between the discrete flavours in attendance. What you taste, instead, is the result of the marriage between all the individual aromatics. You notice less of ‘hey, that’s cumin!’ when the flavours intermingle and get to know each other. The result? A more well-rounded taste. Umami, the illustrious sixth flavour, becomes more perceivable.

That isn’t all. When cooled, flavour molecules are better able to impregnate the protein or starch in your dish. Potatoes soak up a curry sauce, lentils saturate themselves with broth, the cauliflower in your aloo gobi tastes less of, well, cauliflower. This is all down to the structural transformation the starch or protein goes through when cooked and subsequently cooled, trapping the flavour compounds within as the temperature plummets. The texture of the sauce itself changes from something thin and watery, to a thick velvet gloss.

But not all leftovers are created equal. While curries and stews have much to gain from some time in the refrigerator, some dishes are left worse for wear. Salads already slick with vinaigrette wilt into a tangled leafy mess, thick batons of fries become mealy, seafood – well, let’s not even go there. How is one to navigate the seemingly capricious world of leftovers and decide what will make a better next-day meal? The answer, my dear Watson, is elementary. Anything that contains a multitude of aromatics, be it herbs, spices or alliums, make leftover heroes. An omelette brimming with garlic, chives and chilli is much improved after some rest, a plain omelette less so.

Now that you are armed with the science behind leftovers, what will you do with it? If you are a meal prepper (and therefore a better human than I am), take note. Meal prep curries, or pillowy noodles of lasagne striated with herby sauce. Leave that sandwich behind, or you will be the poorer for it. You want something that shines after being reheated, rather than something that leaves much to be desired. Season your dish well the first-time round, and then embellish even more after a reheat – tufts of herbs, a flourish of lemon juice.

Now, a mandatory disclaimer. Leftovers, while great, can be a risky business if you aren’t careful about it. Please, handle food safely. After cooking a dish, refrigerate it as soon as you can - no languishing on the kitchen counter for hours on end. But never too quickly – plunging a lunchbox full of food that radiates heat into a refrigerator can warm up the rest of its contents. You want food to cool to about 26 to 30 degrees (roughly room temperature) before you can pop it in for a chill, which should take about 30 minutes. Treat your leftovers well and it will behave itself.

Welcome, young grasshopper, to leftover nirvana.

Image Credit: Kathleen Franklin

0 notes

Text

The Febu-NON-dairy Showdown

Have you ever found yourself lost in the non-dairy aisle, flummoxed by the sheer volume of non-dairy milk in front of you? Which to choose? Which brand? What on earth is pea milk? In this wholly scientific (Sample population – One. Me.) we take an in-depth look at which non-dairy beverage performs best in several milk-requiring situations you may find yourself in.

For your cuppa There is simply no better bedfellow for your coffee or tea than oat milk. It is creamy, has a neutral flavour, and is the only plant milk that steams up, like a cloud, giving you the perfect microfoam on top your morning latte or cappuccino. Good microfoam means good latte art. Which, obviously, means a cuppa good enough to snap for Instagram, if that’s your jam. Oat milk is also, as a perk, the plant milk that requires the least amount of water to produce – good for your cuppa, and for the planet. The soy milk that is preferred by cafes and the like is a good second, only because soy has a more assertive taste than oat does, and certain brands tend to curdle when met with the acidic tea or coffee, giving you a coffee that is speckled with flecks of soy clumps. Not sexy. For the best bet, get a barista soy milk – these tend to be more resilient – and warm the milk up before adding to your coffee/tea situation. The sudden change in temperature you get from plunging fridge-cold soy milk into a hot beverage, more often than not, freaks your soy milk out and causes it to seize. We like: Oatly Barista Edition, £1.80, Tesco / Alpro Barista Soya UHT, £1.90. Sainsbury’s

To drown your cereal or thicken your porridge I know the joke has been made before, but I will make it again. Oat milk and oats – oatception, if you will – are an excellent pair for the ultimate porridge situation. The perfect example of ingredients coming full circle. On the same thread, rice milk is slightly sweeter than oat and works well to perk up any bowl of cereal. Particularly the bran-y, whole-wheat, no-fuss sort (I am looking at you, all-bran). If you prefer your cereal on the sugary side – pick oat over rice as it won’t overwhelm your palate, but will still provide the creamy velvet background number to your cereal-saturated breakfast. We like: Rice Dream Original, £1.55, Waitrose / Oatly Original Oat Drink, £1.50, Sainsbury’s

For baking Soy milk matches dairy milk in its silkiness, and because of this, it can be used as a substitute, in equal proportions, for dairy milk in your favourite baked good. Its distinctive soy flavour mellows out when subject to the heat of the oven, so don’t let that worry you. Soy is also the best of all the non-dairy milk for a buttermilk substitute, where its coagulation property rather works in your favour. Before I went vegan, whenever a recipe called for a cup of buttermilk, I would fill a cup measurement with a tablespoon of acid (lemon juice, vinegar, et cetera), then top it up with dairy milk. When left to its own devices, the acid causes the milk to thicken and curdle. Soy appears to be the one non-dairy milk that performs this role just as well. Since you will be baking with it, I tend to go for whatever is cheapest, and Tesco’s home brand version has been instrumental to all my vegan baking experiments. We like: Tesco Longlife Unsweetened Soya Milk Alternative, £0.85, Tesco

For savoury cooking If your next savoury dish requires a splash of milk (soups, pasta sauces, or similar) – two of the plant milk rise above the rest. Hemp milk, with its ever-so-slightly vegetal taste, works well when paired with grains or pulses. The herbaceous quality of it bounces off the neutral, grainy taste of quinoa – for example. For something slightly more neutral where there are already a lot of flavours in attendance, cashew milk imparts maximum creaminess with only a vestige of a pleasant nutty taste. We like: Good Hemp Creamy Seed Milk, £2, Sainsbury’s / Plenish Organic Cashew M*lk, £2.55, Waitrose

For the whipped-cream enthusiast I always keep a tin of coconut milk (none of the low-fat stuff, please) in my fridge, ready to deploy whenever a dessert calls for a crowning of whipped cream. When picking a brand to use for your next dessert, keep two things in mind. One, the higher the fat content the better; and two, try to find one with little or no stabilisers (Guar Gum, Carboxymethylcellulose…). The Essential Waitrose brand has never failed me. Keep a can in the fridge overnight. Open it, and scoop out the thick, solidified coconut cream that will have settled in a layer on the top of the can, leaving the clear coconut water behind. Use a hand whisk, or sheer elbow grease, to whip as much air as you can into the coconut cream. The colder it is the better your whip. Keep whatever residual coconut water you have – the high electrolyte content makes it a great post-workout drink, and it also makes a terrific addition to a smoothie. We like: Essential Waitrose Coconut Milk, £1.55, Waitrose

For the ambitious vegan ice-cream maker I use the word ambitious, here, because ambition is necessary to cultivate the compulsion to make one’s own ice cream. But if you are a better person than I am, and resolve to make your own non-dairy frozen dessert (we aren’t legally allowed to call it ice cream, with it lacking the cream and all…) – pick a higher fat plant milk. Coconut reigns supreme here, and just like for a good whip, look for more fat and less stabilisers. If you are looking for a lower fat option, consider using soy milk – although your resulting ice cream (pardon me – frozen dessert) may not be nearly as luscious. We like: Essential Waitrose Coconut Milk, £1.55, Waitrose / Alpro Soya Unsweetened Longlife Drink Alternative, £1.30, Tesco

For drinking, solo. With a cookie, perhaps. One of life’s simple pleasures involves a cookie and a cold glass of milk. Some alchemy is at work here, giving you a treat that is greater than the sum of its parts. Rice milk, with its sweet subtlety and velvety mouthfeel, works wonderful tricks when it is soaked up by the cookie. It is also perfect as a stand-alone drink – and while I was never the sort of person to neck a glass of milk when I was parched – I am perfectly content with a glass of ice-cold rice milk to sip on. I imagine that Santa wouldn’t mind in the slightest. We like: Rice Dream Original, £1.55, Waitrose

For the Health Junkie And now – a curveball. Sure, we all know almond milk. You may already hold a special place in your heart for Oatly. What was once bizarre (you can milk a nut?!?) we have since come to accept without much thought. When I first heard of pea milk, I thought it was a step too far. Come on, milk from peas? I spotted it on offer a couple of months ago and decided to give it a whirl. I am happy to report back that pea milk does not, in fact, taste of peas. It is delightfully creamy, thick like soy but with a very slight savoury edge. It has the highest protein content of all the plant milks, perfect for the gym bunny on the quest for a post-workout smoothie. It is hypoallergenic, so if you have a nut allergy (bless you) – here is your answer to delicious, anaphylactic shock-free plant goodness. We like: Sproud Original Pea Milk, £1.80, Waitrose

It is worth adding that while plant milk is a little pricier than the regular ol’ pint of cow’s milk you can grab from Tesco, it is sometimes worth investing a little more in a product that is better for our planet. Every little counts (a fitting phrase to add in here), even if you just swap out for a plant alternative once a week. One or two varieties are, seemingly, always on offer. Since so many of these are shelf-stable, stocking up whenever a discount hits can save you in the long run. Now go forth and proceed to add oat milk to everything you consume, we’ve all been there.

Image Credit: Sasha Gill

0 notes

Text

One man’s trash is another man’s banana bread

We are here, in 2020, a year saturated with students vehemently absolving to reduce their food waste. And here are 10 lesser-known ways (some more abstract) to make it work for you.

1. Watermelon Rind We start off with a bang, for how could you not? If you are ambitious and buy your watermelon—rind and all –I have a challenge for you. As someone who has been in a seven-year love affair with pretty much anything pickled or preserved, I urge you to try pickling the tough, bland rind of the next watermelon you buy. Watermelon pickle plays such astonishing tricks between the sweet and briny flavours of the marinade. Make a pickling brine out of 1 part salt, 8 parts water, 4 parts sugar, and 2 parts acid. This might sound complicated, but if you start with ¼ cup of salt, it would seem less so. Simply whisk your brine together in a saucepan, until you see the faintest smile of a simmer, then dump in at least 5 to 6-cups worth of cubed watermelon rind. Decant into sterile glass jars, and let them cool. After a day or so, they make a terrific sidekick to any burrito.

2. Stale Bread You raise me a stale baton of French baguette—or, indeed, any bread—and I’ll give you several ways to deal with it. Breadcrumbs are my first solution, once hard, like toast but without their burnished goldenness, whizz them up in a processor or bang them with something heavy whilst encased in a freezer bag – and you will have the panko breadcrumbs that supermarkets charge extra for. You can use them wherever panko seems fit, but my favourite will always be to adorn a mac and cheese, or gratin, until the edges turn blissfully, heavenly crisp. Failing that, slice them into thick slices, or cubes, to make an ethereal French Toast, or Bread and Butter Pudding, respectively. If you have had enough foresight to know that a loaf will outlive your week, stick it in the freezer – this avoids the whole kerfuffle of leftovers, and it only takes a minute or so extra in the toaster to perform like freshly-baked bread.