Text

At a festival. Small child is lying on the ground nearby with a large rock on their chest yelling MORE WEIGHT!!! GIVE ME MORE WEIGHT!!!

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday, August 19, 1692

Five witches are loaded into the cart bound for Gallows Hill: George Burroughs, Martha Carrier, George Jacobs, John Proctor, and John Willard. While in prison, Elizabeth Proctor had announced that she was pregnant, and local midwives confirm it before her execution. She is allowed to carry the child to term before being hanged.

It is likely that John Proctor made an impassioned speech to the crowd before his execution, but whatever he said is overshadowed by Reverend Burroughs.

After being lead up the ladder, Burroughs is asked one last time if he wishes to make a confession. Instead, he gazes serenely at the crowd and asks them to pray with him. The bewitched girls mutter that the Black Man is speaking through him, but they are shushed. As his accusers stand in stunned silence, Burroughs preaches his last sermon. Over the next several minutes, he proclaims his innocence and his forgiveness of the accusers, and concludes with a flawless recitation of the most fundamental Puritan prayer, the Lord’s Prayer.

Failure to remember basic prayer is a cornerstone of witchcraft accusation; by Cotton Mather’s own teachings, this is proof that Burroughs is not a witch. The crowd, shouting and moved to tears, begins to beg the executioner to let Burroughs down. Unfortunately, Mather himself has come up from Boston to witness the hanging and quiets the crowd to save his reputation. Mather shouts above the noise that Burroughs’s preaching in meaningless, as he has never been formally ordained. Also, he reminds them, “the devil has often been transformed into an angel of light”.

Burroughs, followed by the others, are hanged and the bodies are thrown into the crevice of the hill. As a final injustice, Burroughs’s clothes are considered too fine to waste, and he is stripped and put into second hand breeches before being hastily disposed of.

George Jacobs’s family later removes his body and buries in by his home.

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thursday, August 18, 1692

Two more witches are brought into custody: Frances Hutchins and Ruth Wilford.

That night, unable to sleep through the guilt and impending executions the next day, Margaret Jacobs begs to see Reverend Burroughs. In his cell, she breaks down and tells Burroughs that her accusations against him and her grandfather were false; she had accepted the magistrates bargain and sold them out in exchange for her own life. Sobbing, she begs Burroughs’s forgiveness. He spends the night praying with her and the others who are to be executed the next morning.

Reverend Noyes offers to pray with John Proctor, but only if he will confess. Proctor refuses to speak to him.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saturday, August 13, 1692

One of the confessed witches of the previous day, Elizabeth Johnson, has named Daniel Eames as a fellow witch. Eames is dragged in for questioning.

The afflicted girls accost him, telling him of the various times he has afflicted them, but Eames denies this. He instead asks the magistrates to pray for him.

“I desire in the presence of Jesus Christ that you would pray for me that I may speak the truth,” he says. “He that is the Great Judge knows that I never did council with the devil and do not know anything of it. I never signed no book nor never saw Satan or any of his instruments that I know of.”

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thursday, August 11, 1692

The accused witches from the day before are continually questioned. Because they have confessed, their testimony is needed to name and convict other witches. At this point the magistrates have been offering plea bargains to their prisoners: confess, and you will be kept as a source of information. Fail to confess, and you will be convicted and hanged.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday, August 10, 1692

Martha Carrier’s daughter Sarah, now in custody, is examined and immediately confesses to witchcraft. She has been a witch since she was six years old, she says. Her brother Thomas likewise confesses, recounting that his mother had threatened to kill him if he did not sign the devil’s book, and had baptized him as a witch in the river. Another witness claims that she saw this event and was likewise seduced into being baptized.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

On the road leading into the center of Concord, Massachusetts, there sits a house.

It is a plain, colonial-style house, of which there are many along this road. It has sea green and buff paint, a historical plaque, and one of the most multi-layered stories I have ever encountered to showcase that history is continuous, complicated, and most importantly, fragmentary, unless you know where to look.

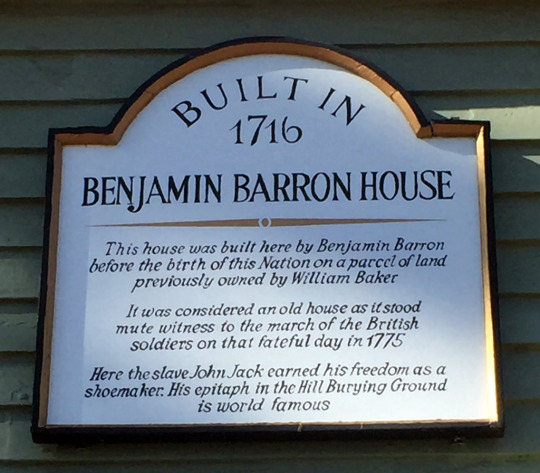

So, where to start? The plaque.

There's some usual information here: Benjamin Barron built the house in 1716, and years later it was a "witness house" to the start of the American Revolution. And then, something unusual: a note about an enslaved man named John Jack whose epitaph is "world famous."

Where is this epitaph? Right around the corner in the town center.

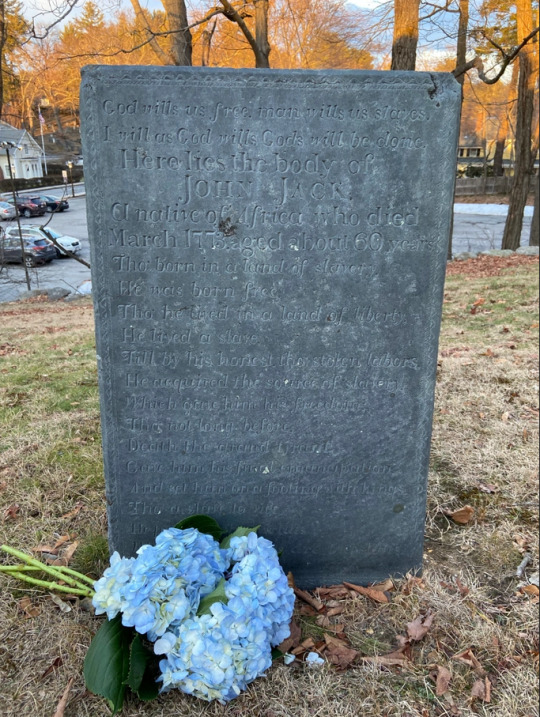

It reads:

God wills us free; man wills us slaves. I will as God wills; God’s will be done. Here lies the body of JOHN JACK a native of Africa who died March 1773 aged about 60 years Tho’ born in a land of slavery, He was born free. Tho’ he lived in a land of liberty, He lived a slave. Till by his honest, tho’ stolen labors, He acquired the source of slavery, Which gave him his freedom; Tho’ not long before Death, the grand tyrant Gave him his final emancipation, And set him on a footing with kings. Tho’ a slave to vice, He practised those virtues Without which kings are but slaves.

We don't know precisely when the man first known only as Jack was purchased by Benjamin Barron. We do know that he, along with an enslaved woman named Violet, were listed in Barron's estate upon his death in 1754. Assuming his gravestone is accurate, at that time Jack would have been about 40 and had apparently learned the shoemaking trade from his enslaver. With his "honest, though stolen labors" he was then able to earn enough money to eventually purchase his freedom from the remaining Barron family and change his name to John, keeping Jack as a last name rather than using his enslaver's.

John Jack died, poor but free, in 1773, just two years before the Revolutionary War started. Presumably as part of setting up his own estate, he became a client of local lawyer Daniel Bliss, brother-in-law to the minister, William Emerson. Bliss and Emerson were in a massive family feud that spilled into the rest of the town, as Bliss was notoriously loyal to the crown, eventually letting British soldiers stay in his home and giving them information about Patriot activities.

Daniel Bliss also had abolitionist leanings. And after hearing John's story, he was angry.

Here was a man who had been kidnapped from his home country, dragged across the ocean, and treated as an animal for decades. Countless others were being brutalized in the same way, in the same town that claimed to love liberty and freedom. Reverend Emerson railed against the British government from the pulpit, and he himself was an enslaver.

It wouldn't do. John Jack deserved so much more. So, when he died, Bliss personally paid for a large gravestone and wrote its epitaph to blast the town's hypocrisy from the top of Burial Hill. When the British soldiers trudged through the cemetery on April 19th, 1775, they were so struck that they wrote the words down and published them in the British newspapers, and that hypocrisy passed around Europe as well. And the stone is still there today.

You know whose stone doesn't survive in the burial ground?

Benjamin Barron's.

Or any of his family that I know of. Which is absolutely astonishing, because this story is about to get even more complicated.

Benjamin Barron was a middle-class shoemaker in a suburb that wouldn't become famous until decades after his death. He lived a simple life only made possible by chattel slavery, and he will never show up in a U.S. history textbook.

But he had a wife, and a family. His widow, Betty Barron, from whom John purchased his freedom, whose name does not appear on her home's plaque or anywhere else in town, does appear either by name or in passing in every single one of those textbooks.

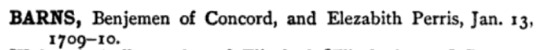

Terrible colonial spelling of all names in their marriage record aside, you may have heard her maiden name before:

Betty Parris was born into a slaveholding family in 1683, in a time when it was fairly common for not only Black, but also Indigenous people to be enslaved. It was also a time of war, religious extremism, and severe paranoia in a pre-scientific frontier. And so it was that at the age of nine, Betty pointed a finger at the Arawak woman enslaved in her Salem home, named Titibe, and accused her of witchcraft.

Yes, that Betty Parris.

Her accusations may have started the Salem Witch trials, but unlike her peers, she did not stay in the action for long. As a minor, she was not allowed to testify at court, and as the minister's daughter, she was too high-profile to be allowed near the courtroom circus. Betty's parents sent her to live with relatives during the proceedings, at which point her "bewitchment" was cured, though we're still unsure if she had psychosomatic problems solved by being away from stress, if she stopped because the public stopped listening, or if she stopped because she no longer had adults prompting her.

Following the witch hysteria, the Parrises moved several times as her infamous father struggled to hold down a job and deal with his family's reputation. Eventually they landed in Concord, where Betty met Benjamin and married him at the age of 26, presumably having had no more encounters with Satan in the preceding seventeen years. She lived an undocumented life and died, obscure and forgotten, in 1760, just five years before the Stamp Act crisis plunged America into a revolution, a living bridge between the old world and the new.

I often wonder how much Betty's story followed her throughout her life. People must have talked. Did they whisper in the town square, "Do you know what she did when she was a girl?" Did John Jack hear the stories of how she had previously treated the enslaved people in her life? Did that hasten his desperation to get out? And what of Daniel Bliss; did he know this history as well, seeing the double indignity of it all? Did he stop and think about how much in the world had changed in less than a century since his neighbor was born?

We'll never know.

All that's left is a gravestone, and a house with an insufficient plaque.

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday, August 5, 1692

The most anticipated trials are held for the spectators of Salem Village: outspoken husband and wife team Elizabeth and John Proctor and Satanic minister George Burroughs are brought before the jury.

Several petitions have been sent to the court in defense of the Proctors, including mention of the girl who had falsely cried out Goody Proctor’s specter in the tavern before her examination, but these are overshadowed by spectral evidence, physical evidence in the form of poppets, and documented servant-beating.

Mary Warren and many of the other bewitched girls recount spectral beatings by the couple while contorting themselves during the proceedings. The specters of the couple tormented the girls during the original examinations, the jury is reminded, and they continue to do so now. Warren leads the group in screeching about pinches, pricks, bites, and burns. Other witnesses have seen these specters at work as well.

More damaging is John Proctor’s insistence in the insanity of his fellow Villagers. Several times he has been heard badmouthing the afflicted girls, calling them spoiled and in need of a beating. His skepticism goes beyond the immediate proceedings, as questioning the girls’ motives can be seen as questioning religious doctrine, as well as the credibility of influential officials who have believed the case from day one.

Despite his prestigious background, Burroughs is thought by many to be the “head actor at some of their hellish rendezvous, and one who had the promise of being a king in Satan’s kingdom”. Like the other men, Burroughs has a long history of domestic violence and surprising strength, in addition to damning testimony by the ghosts of his dead wives and the many accused witches of his being in charge of black Sabbaths with red wine and bread.

Burroughs’s ministerial background haunts him as witnesses come forward to warp Biblical texts in his name, such as Mercy Lewis, who testifies that, like Satan to Jesus, Burroughs had taken her to a high place and offered her all the kingdoms of the world. She would not yield, she said, even if thrown on a thousand pitchforks. Ann Putnam Jr., likewise, writhes on the floor and cries that the “little black man” is shoving his demonic book at her. Burroughs already has a history of living among, if not fraternizing with the Indians, and Putnam has already accused him of bewitching soldiers fighting them.

As the accused tell their stories, they frequently fall into fits and are unable to speak. When confronted about this, Burroughs acknowledges that the devil may be hindering them, but seems confused as to why.

Burroughs has a final retort, however: when asked to defend himself before the jury, he produces a written speech, in which he states that having heard the accusations against him, he is now convinced that “there neither are, nor ever were, witches, [and} that having made a compact with the devil, can send a devil to torment other people at a distance.” With this simple sentence, Burroughs shatters Puritan theology: not only does he deny spectral evidence, but witchcraft itself. If witches do not exist, neither does the devil. If the devil does not exist, neither does God.

All three are found guilty.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thursday, August 4, 1692

Two new trials are heard today, of George Jacobs and John Willard, who have uncharacteristically been dragged into the hysteria despite their sex and lack of intimacy with other accused female witches.

George Jacobs, due to old age, has unfortunately had a higher chance of possessing a witch’s teat, George Herrick had looked for one during the original examination and and found it, testifying to its existence on “his right shoulder…about a quarter of an inch long or better wit a sharp point draping downwards”. Herrick had pierced the teat with a needle and found that it did not bleed.

Jacobs also had damning evidence in carrying the sticks he supposedly beat his victims with, although he needed them to stand. Both the physical and spectral Jacobs is accused of beating servant Mary Warren and others with these sticks. Despite this infirmity, Jacobs is charged with threatening and nearly drowning people. As with other cases, several ghosts have appeared to witnesses, claiming that Jacobs had murdered them.

Lastly, Jacobs’s granddaughter Margaret is still a confessed witch. A witness confides to the jury that upon being told that Margaret had confessed, Jacobs told him that if she was innocent but falsely confessed, then she would be “an accessory to her own death”.

John Willard, like George Jacobs, has charges of domestic violence, rather than witchcraft, as the backbone of his accusations. Strange sounds also seem to accompany him, which he has blamed on locusts, and he has been known to exhibit inhuman strength and speed. Various victims come forward, claiming to have been afflicted after displeasing him.

An old man named Bray Wilkins tells a story of Willard coming to his home and begging him to pray for him shortly after the accusations started. Bray was just leaving and stated that he would happily pray if he got back before dark, but did not. Convinced that he had offended Willard, Bray blames him for later glaring at him at a party and causing a urinary infection. Reverend Lawson and Mercy Lewis, he says, are of the same opinion.

Both men are found guilty.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday, August 3, 1692

The grand jury begins to hear tales of rogue minister George Burroughs, as well as Mary Easty, also a sister of Rebecca Nurse. While this is going on, Martha Carrier comes to trial, riding on recent accusations by her children and Foster.

Carrier’s neighbors begin the testimony with familiar stories of land disputes followed by suspicious illness of both people and cattle. One woman reports Martha’s disembodied voice coming out of a bush and questioning her and threaten to poison her. The Putnams come forward to remind the jury of the afflicted girls’ torments during Carrier’s examination back in May - “Had not the magistrates commanded her to be bound,” they say, “we were ready to think she would quickly have killed some of them”.

Like other trials, most of the evidence given is years old and includes violent altercations with Carriers sons, rather than with the suspected witch herself. Although Carrier is only on trial for bewitching a small cohort of afflicted girls, her neighbors’ testimony is needed by the judges to convict her, as they are not meant to use spectral evidence alone.

The verdict: guilty.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tuesday, August 2, 1692

Another new witch is in custody, Martha Post, as testimony against accused witches soon to be on trial continues to pour in.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saturday, July 30, 1692

When several witnesses who did not know Hannah Bromage are asked to take her hand, nothing happens, but Mary Walcott and Ann Putnam Jr. begin to seize. Upon touching them again, the girls say that they are cured. The afflicted girls urge Bromage to confess, but she refuses them, saying that the devil might be in her heart, but she was not a witch.

Meanwhile, Roger Toothaker’s widow is also examined. After seeing several afflicted girls fall down before her, Mary Toothaker explains that the devil had come to her when she had dreams about fighting against the Indians on the frontier. He had often stopped her from praying, she says, for two years, and urged her to make poppets to torment others. Rather than a book to sign, he had brought her a piece of birch bark which she scratched her mark into.

During questioning Toothaker names the other recently accused as well as her own sister, who were with her at one of George Burroughs’s black Sabbaths. They had vowed, she said, to bring down the kingdom of God in favor of a kingdom of Satan, with the help of the 305 witches other confessed had already mentioned.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thursday, July 28, 1692

Goodwife Green, also known as Mary Green, has been located in Haverhill. She is ordered to be arrested along with Mary Bridges and Hannah Bromage.

Mary Bradbury’s husband submits a heartfelt petition stating that after fifty-five years of marriage, “she hath been a loving and faithful wife to me; unto this day she hath been wonderful, laborious, diligent and industrious in her place and employment about the bringing up of family, which having been eleven children of her own and four grandchildren, she was both prudent and provident, of a cheerful spirit, liberal and charitable”.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saturday, July 23, 1692

Martha Emerson, Carrier’s great-niece, is hauled into the meeting house, but refuses to acknowledge any wrongdoing. Richard Carrier is willing to confess for her, however. Mary Warren and Mary Lacey also fall down in her presence.

Emerson is confronted with the rumor that her father had given her a recipe to kill a witch, similar to the witch cake John Indian had made months prior. Having been confronted with evidence of having put a jar of urine in the oven, Emerson claims that she wishes to confess, but Carrier and a Goodwife Green of Haverhill are preventing her from doing so.

Meanwhile, in prison, John Proctor write an impassioned plea to the government.

“The innocency of our case with the enmity of our accusers and our judges, and jury, whom nothing but our innocent blood will serve their turn, having condemned us already before our trials, being so much incensed and engaged against us by the Devil, makes us bold to beg and implore your favourable assistance of this our humble petition to his excellency, That if it be possible our innocent blood may be spared, which undoubtedly otherwise will be shed, if the Lord doth not mercifully step in.”

Proctor explains that the Carrier boys had only confessed after several days of torture, having been tied “neck and heels til the blood was ready to come out of their noses”. Proctor’s son had been handled in a similar way, but had not confessed and was eventually untied after he began to bleed.

He begs the governor to hire new judges and magistrates, and to witness the trials himself to see the cruelty that has been exhibited.

“We rest,” he writes, “your poor afflicted servants”.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday, July 22, 1692

A new suspect, Martha Emerson, is apprehended as the Carriers and Laceys are interrogated again.

The boys claim that the devil prevents them form confessing, but Mary Lacey provides information. Afterward Richard confesses that he is “in the devil’s snare” and that his brother has been a witch for a month.

A new petition has also come in for another accused witch, Mary Bradbury. Several dozen signers attested “that it was such as become the gospel, she was a lover of the ministry…being of a courteous and peaceable disposition and carriage…always ready and willing to do for them what lay in her power night and day”.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thursday, July 21, 1692

Two more Carriers are now in custody: Richard and Andrew.

Three generations of witches are also brought in for questioning, beginning ith Ann Foster, who the magistrates hope will supply valuable information now that she has confessed. One of them interrogates her regarding her daughter, whom Foster claims is not a witch. Despite having confessed, Foster refuses to name any witches besides Carrier.

Foster’s daughter and granddaughter, however, confess under the brutal interrogation. Lacey Jr. tells a vivid tale of meeting the devil for over a year, but becoming a witch only the week before. She names Richard Carrier as another witch.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wednesday, July 20, 1692

Early in the morning, Francis Nurse and several of his children silently paddle a boat down the stream to the base of Gallows Hill. There, they remove Rebecca Nurse’s body from the crevice and bring her home, where they bury her in an unmarked grave in the family burying ground behind their home. It is assumed that the families of the other victims did the same.

After hearing complaints from Joseph Ballard, Ann Foster’s daughter, Mary Lacey and her daughter, also named Mary, are arrested.

7 notes

·

View notes