Text

“I think... if it is true that there are as many minds as there are heads, then there are as many kinds of love as there are hearts.” ― Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

Painting: Embrace II from the series “Surfacing” by Ron Hicks

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

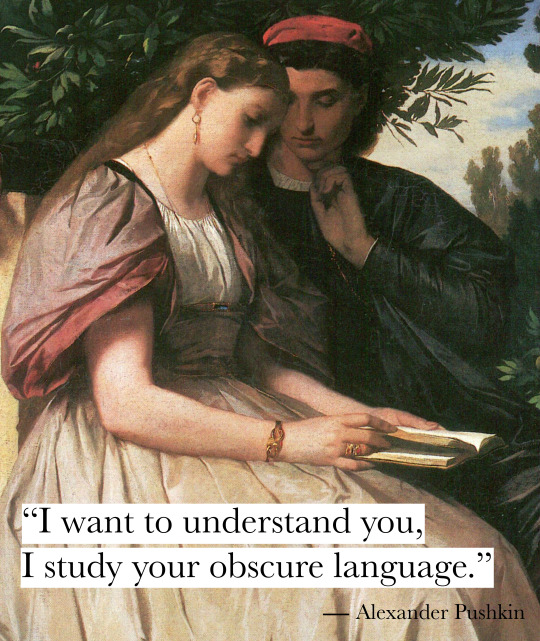

“I want to understand you, I study your obscure language.” ― Alexander Pushkin

Painting: "Paolo und Francesca" by Anselm Feuerbach

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twin Peaks & Hauntology

A large deal of David Lynch’s content is surreal not just because of how odd it is, but also because of how familiar it is: For many entering the Twin Peaks universe in contemporary times, they have already been exposed to some imagery from the show or from David Lynch’s other work, which often makes many parallels to the show itself. For instance, prior to starting the original run of the series, I had indeed seen the classic portrait of Laura Palmer a myriad of times and knew the famous lines, “who killed Laura Palmer?” I had seen some of Lynch’s work too, and I also had in fact seen plenty of references to Twin Peaks in pop culture, but it was only when I began to immerse myself in Twin Peaks that I could say to myself, “this feels like deja vu.” The cinematography, the color palette, the dated film quality, the eerie music, everything about the show is setup so that it feels haunted, both from within its own universe and for those observing as though external spectators. Essentially, one of the main reasons why Twin Peaks is such a successful show in terms of endearment and also producing chilling reactions, is because it plays to humanity’s fragmented memories of time, rejecting a linear framework in favor of something that is more distinctly postmodern (i.e. time is not treated as a straight arrow as is the case for most shows). David Lynch innately flirts with these concepts throughout his career in philosophical and psychological manners that make many uneasy from various standpoints, including the metaphysical and ontological. One tiny yet distinctive and slowly emerging school of thought to grow out of the postmodern field of study is hauntology, coined by the French philosopher esteemed for his take on deconstructionism, Jacques Derrida, in his 1993 book, “Specters of Marx.” All things considered, Twin Peaks is an excellent example of hauntology expressed through an artistic medium, and here is some elaboration as to how and why.

So what is hauntology? Derrida originally developed the idea as a portmanteau of haunting and ontology, ontology being the study of life, hence “hauntology.” Specifically, his aforementioned book from 1993 extensively developed Karl Marx’s idea that “A specter is haunting Europe – the specter of Communism.” These were the opening lines to “The Communist Manifesto,” published in 1848 and yet managing to have widespread appeal on a major political levels, well over a hundred years after it had been written and even to this day, proving that Marx was right – Communism is haunting Europe and the rest of the world, chiefly due to the fact that it exists in opposition to the dominant mode of production around the globe, capitalism, but also because according to many scholars, we are perhaps living in a late stage of capitalism that is in fact quite similar to what Marx and his contemporaries envisioned, a stage of decay and corruption that gives way to a fork in the road of fascism, corporatism, and the like, but could also bring forth major developments in class consciousness with regards to revolution and unification. By treating Communism as a specter, it is essentially a faceless character, looming and lurking in the shadows, a ghostly apparition that either instills terror or hope into the hearts of those who find it depending on what side of the political spectrum they are on. Derrida also ties this idea into the Shakespearean play, “Hamlet,” which also began its first lines (“Who’s there?”) in a haunted sort of manner, involving an actual ghost. With regards to Hamlet, Derrida specifically makes note of how “the time is out of joint,” a similar occurrence to real world matters such as Communism and fictional matters such as Twin Peaks.

As Andrew Gallix of The Guardian describes hauntology, it is: The situation of temporal, historical, and ontological disjunction in which the apparent presence of being is replaced by an absent or deferred non-origin, represented by “the figure of the ghost as that which is neither present, nor absent, neither dead nor alive.” Peter Bruse and Andrew Scott further elaborate that: “Ghosts arrive from the past and appear in the present. However, the ghost cannot be properly said to belong to the past. Does then the ‘historical’ person who is identified with the ghost properly belong to the present? Surely not, as the idea of a return from death fractures all traditional conceptions of temporality. The temporality to which the ghost is subject is therefore paradoxical, at once they ‘return’ and make their apparitional debut.” From here, we note how Derrida’s own writing focuses on the presumed “death” of Communism in the post-Soviet world, the question of “the end of history” and most significantly, “if Communism was always spectral, what does it mean to say it is now dead?” All of these concepts tie into the lost futures of modernity, and as Wikipedia writes in depth: “Hauntology has been described as a ‘pining for a future that never arrived;’ […] hauntological art and culture is typified by a critical foregrounding of the historical and metaphysical disjunctions of contemporary capitalist culture as well as a ‘refusal to give up on the desire for the future.’ [Mark] Fisher and others have drawn attention to the shift into post-Fordist economies in the late 1970s, which Fisher argues has ‘gradually and systematically deprived artists of the resources necessary to produce the new.’ Hauntology has been used as a critical lens in various forms of media and theory, including music, political theory, architecture, Afrofuturism, and psychoanalysis.”

Now, regarding hauntology more as an artistic statement and genre than as something philosophical is the first way we can approach Twin Peaks. The style is unique yet also not: It is, as expressed by one of the most prominent artists of the style, Boards of Canada, “the past inside the present.” Most notably, hauntological art is expressed in music, paying homage to library music, vintage documentary-film scores, public information films, etc. This means a heavy dosage of old-school synthesizers, blips and bloops, samples of dialogue from long forgotten movies, and so forth. What we have on our hands here, is “21st-century musicians exploring similar ideas related to temporal disjunction, retrofuturism, memory, the malleability of recording media, and esoteric cultural sources from the past. Artists associated with hauntology include members of the UK label Ghost Box (such as Belbury Poly, The Focus Group, and the Advisory Circle), London dubstep producer Burial, electronic musicians such as the Caretaker, William Basinski, Philip Jeck, Aseptic Void, Moon Wiring Club, and Mordant Music, American lo-fi artist Ariel Pink, and the artists of the Italian Occult Psychedelia scene. Common reference points include library music, the soundtracks of old science-fiction and pulp horror films, found sounds, analog electronic music, musique concrète, dub, decaying cassette tapes, English psychedelia, and 1970s public television programs. A common element is the foregrounding of the recording surface noise, including the crackle and hiss of vinyl and tape, calling attention to the medium itself.”

Furthermore, “’hauntological music has been particularly tied to British culture, and has been described as an attempt to evoke ‘a nostalgia for a future that never came to pass, with a vision of a strange, alternate Britain, constituted from the reorder refuse of the postwar period.’ Reynolds described it as an attempt to construct a ‘lost utopianism’ rooted in visions of a benevolent post-welfare state. According to Fisher, 21st-century electronic music is the anachronistic product of an ‘after the future’ age in which ‘electronic music had succumbed to its own inertia and retrospection … What defined this ‘hauntological’ confluence more than anything else was its confrontation with a cultural impasse: the failure of the future….’ He explains that this is partly the result of stagnated technical advances since the 20th-century. The style has been described as the British cousin of America’s hypnagogic pop music scene, which has also been discussed as engaging with notions of nostalgia and memory. The two styles have been likened to ‘sonic fictions or intentional forgeries, creating half-baked memories of things that never were—approximating the imprecise nature of memory itself.’ Early progenitors of the style include Boards of Canada and Position Normal.”

Lengthy quotes aside, the basic message is that hauntological art – particularly music – is dreamlike, vaguely nostalgic, and ghostly. Basically, musical deja vu. One could make a case that popular genres like chillwave and synthwave, which rely heavily on ‘80s aesthetics are also hauntological, but they lack the same sense of “dread” and “fragmentation” that established artists like Boards of Canada have (e.g. Boards of Canada’s last album, “Tomorrow’s Harvest” is directly linked to the themes of war, apocalypse, the end of history, civilization’s collapse, death and rebirth). The Caretaker, too, is another fantastic example of hauntology: Leyland Kirby publishes records dealing with themes of dementia (the absolution of memory loss) and much of his work is lo-fi, darkly reverberated jazz from no later than WWII; essentially, it is as though history did end with the second war, and when listening to The Caretaker, we are hearing ghostly apparitions committed to tape. “An Empty Bliss Beyond This World,” “Everywhere at the End of Time,” the titles of Kirby’s work alone is enough to suggest something hauntological is occurring. Kirby’s music becomes directly relevant to Twin Peaks: The Return when the viewer notes how similar the music and pre-1940s style are to The Caretaker in The Giant’s realm (some have even dubbed The Giant as a cosmic caretaker of sorts ironically enough). But in the meantime, it is important to discuss how this all relates to the original run of Twin Peaks. One may pose the question: “How is hauntology related to Twin Peaks?”

Remember when I said that we should regard hauntology as an artistic statement rather than a philosophical concept? This is the main and most easy way to comprehend the correlation of hauntology and Twin Peaks. In its original time period, airing in the early ‘90s, it appeared as an anomaly of sorts. The artistic style of the show was deeply rooted in something haunting, something to do with deja vu. Angelo Badalamenti, the composer of the show’s soundtrack, is known for his enigmatic and hypnagogic take on jazz and subtle ambient music, which connects quite well to the mysterious nature of everything going on throughout the show. What specifically helps mark a tonality of hauntology is the fact that the music constantly repeats itself, as if a record left on a repeat. And again, the music plays in direct relation to what is happening on the show: As soon as we hear the swelling, swirling synths or the melancholic piano of “Laura Palmer’s Theme,” we know something important is happening, often having to do with memories, or more menacingly, with doppelgangers and shadow realms. When we hear “Audrey’s Dance,” we know something surreal is going to happen, perhaps some backwards talking or a dancing dwarf. The music serves as a sort of specter, haunting the show and allowing us external observers to peer into the Twin Peaks universe and predict what may happen. However, because David Lynch and Mark Frost are masters of surrealist trickery, skepticism sets in: No matter how many times we hear the songs, few will ever know for certain what is going to happen, you just have to make educated guesses, which usually have the right framework (e.g. “something mysterious is about to happen”) but wind up lacking the correct response (e.g. “something mysterious did happen, but it was not at all what I had predicted”). We then become lost in a series of puzzles, clues, a labyrinthine of both artistry and metaphysics; we start to become haunted by our own theories and conjectures. Laura Palmer’s portrait, shots of diners and bars, foggy mountainous forests, elements from the show start to connect to each other but only in fragments, never in wholeness. In a sense, it may reflect upon the age old dilemma’s of duality versus totality, and even idealism versus materialism, but even theories pertaining to those ideas are never fully addressed and in fact there are arguments made that metaphysics and ontology are only meant to serve as emotional and aesthetic tools rather than as literal interpretations. This lack of knowing only deepens the mystery as well as the haunting effects of the show. It leads Twin Peaks to become a sort of solipsistic realm of sorts, and to the viewer, this is both utopian and dystopian; it leads us to become specters in its own twisted way.

There is also the cinematography as previously mentioned. For those watching the original series now, over 25 years after it originally aired, one thing you will notice is the dated quality of the visual imagery. Not in the sense that it has not aged well, but in the sense that everything is shrouded in ‘90s video-haze; subtle, muted colors, VHS-like quality. It adds to the mystique, and further expounds upon the notion of retro-futurism; now in 2017, there is a slew of television shows and movies that visually strive to recreate this retro feeling in the cinematography. Even musicians are becoming increasingly obsessed with this aesthetic, whether displayed in their music videos or in the music itself (beyond hauntology, as mentioned, there has been an increasing rebirth of ‘80s and ‘90s cultural obsession, for instance, vaporwave – which is especially visual and definitively postmodern – and even less abstractly, many major musicians are still drawing heavily from the ‘60s-’70s to the point where Boards of Canada’s unofficial mantra “the past inside the present” rings true). Watching the original series as well as Fire Walks With Me as they aired, untampered and unrestored, the surreal and dreamlike qualities of the show are enhanced, as is the hauntological pathos and logos: Time is thought to repeat itself, as one might say when they observe a new and younger generation of fans watching Twin Peaks. The older fans may note the quality and visual style of the series and feel haunted by it, but even for today’s modern fans, many of them grew up watching things out of the ‘80s and ‘90s and many have been exposed, even if unwittingly, to Lynch and Frost’s work, whether directly or through a more indirect means (e.g. modern shows which draw heavily upon their style, such as Mr. Robot). When the element of familiarity is added to the viewing experience of Twin Peaks, this is where the haunting effect of the show comes into place; viewers may go as far as the ontological route of questioning existential matters, as they find themselves placed in what seems to be a Lynchian role of their own – they are part of the puzzle and by extension, part of the same universe they are watching. While many would argue that time repeats itself, the other argument is more curious than that; time is an illusion, as are many things. The veil of Maya (the illusory nature of existence in Eastern philosophy which Lynch hints at throughout the series) runs deep, and on humanity’s quest to attain Moksha (enlightenment, freedom from the cycle of birth, death, rebirth) we become trapped in our own web of ego, self, identity, thought, emotion, and so forth. We are just as haunted as the characters in Twin Peaks, and when we watch the show, perhaps it is not meant to reflect separate human thoughts but to reflect upon the idea that we are one consciousness collectively and subjectively viewing itself; Twin Peaks is merely a mirror for our own enigma, and even Lynch himself is not free from this matrix as he plays the role of Gordon, because there are quite a few moments, most notably in Fire Walks With Me (e.g. the scene where David Bowie’s character Philip Jeffries vanishes) and in The Return, where even he is just as lost as other characters or viewers, even in spite of the fact that he most likely does possess some deeper knowledge of what is happening.

This brings us, logically, to the next interpretation of hauntology: The philosophical one, keeping in mind the fact that it is meant to represent an ontology, a means of understanding life and death. Twin Peaks does not shy away from the supernatural, and much of the time it would appear at first glance to be purely for showmanship. But the deeper you dive into the lore of the show, whether canonically or through your own interpretations, fandom, etc. the more these supernatural and science-fiction elements may relate to the history, the politics, the ontological, the metaphysical, and the spiritual. In the original show, plenty of nods were made towards Native American spiritualism, Eastern metaphysics, and even on historical levels, oddities like Project MK Ultra come to mind. Even on a sociological level, the show serves as commentary on the nature of small towns, federal versus local justice, human psychology, and so forth. What is problematic for viewers is that everything could be interpreted through very distinct lenses; perhaps the struggle between Leland and Bob represents the Kabbalah’s interpretation of the Sefirot and the Qliphoth (the tree of life and it’s shadowy counterpart respectively – which is especially possible when one watches The Return and notices the arm has now evolved into a tree of sorts). I have seen interpretations of the show that range from Buddhism to Rosicrucian to Masonic, some of which even go as far as casting doubt on the integrity of Lynch and portraying him as an occult figure with some sort of hidden agenda (conspiracy theorists fit right into the realm of Twin Peaks, though I believe most of their cause for panic is just misunderstanding Lynch’s eccentricity and morbid curiosity into hidden realms). The Return has featured the I Ching, Diane wearing colors that reflect upon alchemy, even a sort of genesis myth of Bob and Laura and perhaps everything else that occurs in this universe. The nuclear bomb dropping in the latest episode even brings forth to mind connotations of Shiva, of creation through destruction. Basically, since Lynch and Frost like to keep things secretive and keep us on our toes, we may never know for certain if there is a specific ideological current that fuels the show, if it is just a hodgepodge of different ideas, or if they are trying to say that all interpretations are egalitarian, that “your guess is as good as mine.” The last one would be quite an ontological statement to make, as it reflects upon the ideas of relativity, subjectivity, skepticism, perhaps even nihilism and absurdism; “can we ever find truth? Can we ever know it for certain?” That theme is addressed heavily on the show in various realms of existence, whether pertaining the surface level of reality (Laura’s death) or what may lie beyond (altered states, astral projection, time travel, you name it).

The Return is especially interesting in these regards. First time viewers of the original series were left haunted by their own theories and suspicions for 25 years before Twin Peaks would be visited again in a lengthy format beyond the movie; Twin Peaks faded into cult status, still familiar to many people but often looked upon with an air of uncertainty and wonder. When the show ended, numerous fanzines popped up trying to keep the legacy alive, delivering new theories with each new edition, but this was before the days of major Internet blogging and media distribution, so it was limited and obscure. But even when newer generations started to discuss Twin Peaks online, nothing was ever fully addressed; the haunting still lingered, both by the very facts of how the original show and movie concluded and by the nature of the series as being elusive, hard to pin down, and notorious for not lending viewers much explanation or help. Seeing the series return after being dormant for so long, it is akin to a spectral awakening of sorts. But that is not to say it is no longer haunted, in fact, far from it – Laura’s portrait, her diary entries, her soul, they still float about like ghosts, her theme song still occasionally popping up to haunt, and now the riddles are perhaps even more haunted because we are gaining more glimpses into the supernatural realms of the Lodges and even beyond, into what could be considered a sort of cosmic viewing lens of reincarnation or creationism and then-some. For much of the series so far, viewers have been particularly haunted by wondering when the “real” Cooper would come back, to the point this mystery seems to extend to ourselves: We identify with Cooper, we sympathize with him as being lost and we want him to find his way home because this is the happy ending we all wish for ourselves in life, we all wish to find ourselves and be whole. But as The Return progresses, it becomes increasingly difficult to gauge whether or not this is attainable and feasible, whether because we are looking at things from the wrong angle, because we do not yet have all the puzzle pieces, or perhaps most sinister of all, because of the possibility that we may in fact be a doomed species (something now hinted upon more than ever upon the contextual framework of the atomic bomb, the Dark Mother, the woodsmen, military secrets, etc.). In my opinion, The Return almost serves as a call to arms, that we should invest in more spiritual and metaphysical affairs because there may in fact be some validity to them. Whether or not that means deeply obscure occult references or just casually studying a philosophy is up to you, but I do believe that Lynch has always used his surrealist techniques to promote some form of critical thinking and higher consciousness, to the point where my own takeaway is that he is in fact going the egalitarian route, understanding that each ideology has its own merits and that instead of dogmatically following one, we should find balance. This is the foundation of perennial philosophy, and even in areas such as Thelema can one potentially reach this idea.

Twin Peaks in general reminds me a lot of the story of Lucifer; thought to once be God’s favorite angel, his rebellious nature meant that God cast him out of Heaven and he became a fallen angel. Lucifer’s name translates to “light bringer,” but from there, Lucifer is treated quite differently depending on who you are speaking to. There are many who believe he is Satan, that he is an evil figure commanding demons. There are those who believe him and Satan are one being, with Lucifer representing spiritual enlightenment and Satan representing earthly pleasure. There are those who believe Lucifer, the light bringer, represents our own internal means of achieving enlightenment (he is associated with phosphorus, the light energy essential to DNA) whether through ourselves our through Lucifer as an external deity. In Gematria, a method of interpreting Hebrew scriptures built on computing numerical values of words based on their constituent letters, Lucifer and Jesus both share the same value even. This is all to say: “How do we know the real Lucifer?” and from there, one may even ask the same of Christ, or of all religious figures. Religion is in and of itself a rather hauntological sort of philosophy, precisely because it requires faith in external narratives and storytelling, and much like with Twin Peaks, when the authors of such works are shrouded in enigma, it becomes hard to discern the facts from fiction and conjecture. Luckily, Lynch and Frost are alive for us right now, so their lore may one day be answered directly or we may one day have access to their private writings, but if nothing else, in the meantime, we are to be haunted by their mysteries. Ultimately, my personal belief is starting to become that the show is meant to function as a retelling of spiritual epics such as the creation myth, and their teachings such as Maya versus Moksha. In fact, this might be why some of us find ourselves experiencing such deja vu and familiarity, because in one way or another, we are familiar with what is happening, but the way Lynch and Frost portray the events is done in a new and innovative way that involves a sort of waiting game and a purgatory state of sorts: Twin Peaks was once the most bizarre and surreal show on television, and now from our vantage point in time – even among the postmodern background of a turbulent political, sociological, and metaphysical society – it once again is. Lynch and Frost serve as guiding figures, reminding us that even in the contexts of our most beloved displays of art and spirituality, we should not limit our understanding by just focusing on one source: In order to understand Twin Peaks, we have to look deeper and exercise critical thought, and utilizing a hauntological outlook will surely help viewers discern what is happening with regards to the woodsmen and fragemented, non-linear time narrative that is now occuring on the show.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It haunts, it ghosts, it spectres, there is some phantom there, it has the feel of the living-dead-manor house, spiritualism, occult science, gothic novel, obscurantism, atmosphere of anonymous threat or imminence. The subject that haunts is not identifiable, one cannot see, localize, fix any form, one cannot decide between hallucination and perception, there are only displacements; one feels oneself looked at by what one cannot see.”

— Jacques Derrida, The Specters of Marx

354 notes

·

View notes

Text

Booktok makes me sick, not just because of all the shitty books. It's the prevalence, no, the celebration, of toxic masculinity. Every single booktok book features some variation on the same man. And without fail, against all sensible reason, these characters are portrayed as handsome and charismatic and desirable.

It makes me sick when these authors hold up these toxic, predatory traits and put them on a pedestal as some kind of Ideal Man.

It makes me sick when their aggressiveness and possessiveness is treated as romantic. It makes me sick when these shitty men forcibly grab women, invade their personal spaces, and render them helpless by 'purring' in their ears, every. single. fucking. time.

It makes me sick that these misogynistic, heteronormative, and hypermasculine social conventions keep appearing in so-called feminist literature.

Strip away the idealized elements and you have what is basically the rich, white, cishet, alpha-male archetype. He's tall, usually six feet, physically fit and muscular with obligatory six pack abs, and conventionally handsome, with a chiseled jawline. He's usually clean-shaven, and any hair he may have on his body is minimal. He maintains composure at all times and rarely shows anxiety or uncertainty. He exudes raw charisma and charm and navigates social spaces effortlessly.

His hobbies, if he has any, are stereotypically masculine. When it comes to sex, he's confident, skilled, exclusively dominant, and always knows what to do without communicating with his partner. The sex he enjoys is usually rough, animalistic and overpowering. He may have been with several women in the past, and he may be regarded as a sex god, both in-universe and out.

His toxic traits are rarely portrayed as negative. But when they are, they're usually held up as some edgy, anti-hero persona and the reader is inevitably manipulated into sympathizing with him. He'll be portrayed as a tortured, wounded animal, and his female love interest (and, by proxy, the reader) will decide on some variation of 'I can fix him'.

He is essentially the unrealistic standard the ideal Proper Man; the one that men are expected to emulate, and that women are expected to swoon over.

But what really irks me is the lost potential.

If there are men who don't fit into this mold, they are depicted as pathetic, ineffectual, or any number of negative traits.

The narrative quietly and passive-aggressively mocks them and portray them as boring and un-sexy.

After all, is this the kind of man who will bravely swoop in and sweep a helpless woman off her feet? Of course not. Such men are boys. Wimps. Cowards.

These books are supposed to be fantasy: a genre in which easily anything can be explored. If faeries, magic, and contrived mating bonds can exist, then why can't we also have male characters who exist outside the stereotypical, hypermasculine mold?

Why is it that we can have so many fantastical, impossible, and wondrous magical forces, creatures, and peoples, but we can't have men who aren't possessive, abusive, or controlling?

Why is it that male characters, have to be so innately dominant, abusive, and violent? Why do they have to be so fit and muscular and strong?

Even worse, why is it treated as something that is so natural, so inescapable, even in the realm of fiction?

Where are the men who aren't tall and fit? Where are the men who don't have sculpted abs or chiseled jawlines? Where are the men who aren't lean and muscular?

Why can’t we have men who are skinny or overweight? Why can't we have men who aren't handsome or attractive, but just average looking? Why can't we have men who are shorter or just average height?

Why can't we have men with non-stereotypical hobbies? Why can't we have men who love to read, or paint, or write, or sing, or dance, or build model kits?

Why can’t we have men who are timid and shy? Why can't we have men who feel anxiety, fear, and sadness? Why can't we have men who aren't afraid of crying openly?

Why can't we have men who aren't sex gods? Why can't we have men who aren't confident in bed? Who are anxious, or even scared, at the prospect of sex? Who are passive instead of dominant? Who want to experience intimacy and affection?

Why can’t we have men be kind and gentle and sweet for once?

I'll tell you why we can't. Because booktok says men like these are not 'man' enough. Booktok says men like these are the 'boring' option, and completely devoid of interesting quirks, traits or personality. Booktok says men like these are underserving of attention, and only fit to be background noise.

As far as booktok is concerned, men like these can't exist.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

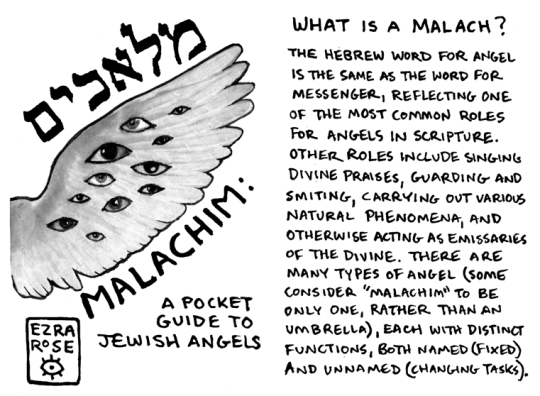

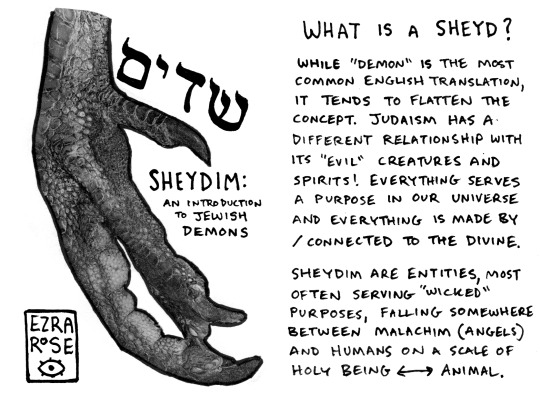

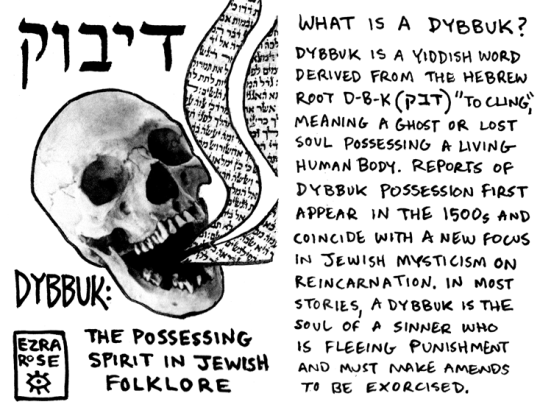

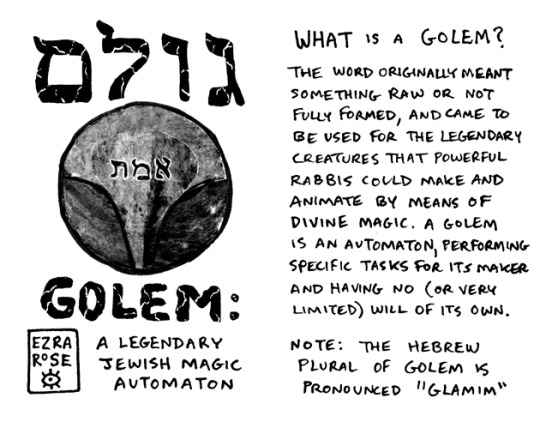

Pages from mini zines about Jewish folklore (the series includes zines on golems, dybbuk, malachim and sheydim) by illustrator / zinester, Ezra Rose. Buy them here and pay what you like.

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my favorite changes from book to movie: Snow doesn’t directly learn about what his father did until the very end.

We know, from both book and film, that there is a small part of him—even in his corrupted, past-redemption state—that regrets what happened with Lucy Gray. That at least acknowledges the love, in his twisted way.

Tom Blythe was such a master at this. But I love the little stab of rage that, for me, foreshadowed the manner of Donald Sutherland’s unwinding for Katniss and Peeta, more than anything else in the film—even the obvious references.

It was that moment, just before Dean Highbottom chugged the poisoned morphling and died, when he laid it out for him—the school assignment, turning it in behind his back, how his father had insisted on it. His father. His dead, absent, poisonous father, who died in the woods in Twelve, who Tigris had compared him to, whose patriarchal oppression had been one of the main forces that ruined his life.

His father had put Lucy Gray in the Games. His father had started everything.

He doesn’t snap. He leaves the poison and walks away. But you see the hatred flash across his eyes before he does. And I LOVED IT

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

Coriolanus snow is capable of love, he is not capable of accepting it. We are constantly reminded by his need of absolute control, possibly stemming from a childhood during which he could control nothing. He couldn't control his surroundings, his safety, his food. His mother died because of lack of order. It could explain why he's so obsessed with it. He has a tendency to control everyone he loves, like thinking about selling Tigris, or continuously saying lucy gray belonged to him. When sejanus decided to betray the Capitol, Snow realized he couldn't control him anymore, and decided to kill him, even though he was fond of him, if not loved him. The mockingjays were such a threat for him because they weren't supposed to exist, yet enjoyed life free of all regulations. He wanted lucy gray attached to him, controlled and subdued. He truly loved her but a glimpse of her free in the wild was enough to send him spiraling. Coryo felt true love but it was such a wild emotion, so impossible to control that he killed it himself.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

TBOSAS and why you shouldn’t feel bad for being attracted to Coriolanus Snow.

(1) Coriolanus is so baby girl/relatable because his initial condition is not unlike a woman’s in society. He describes being frail at the beginning and lacking raw strength due to malnutrition. He also describes being a child and helpless during the rebellion, so all he has are social and intellectual games (his own charms). While he is good at these games, he also hates that he lacks the raw power to not need them. That’s why he is so empowered by exerting brute force over others and enjoys the feeling of being hardened and fed in the peacekeepers.

This position is not unfamiliar to most women. It goes without saying that in the State of Nature, women are equally at risk for starvation and violence, but we’re also at a special outsized risk of sexual violence as well. So more than most men, women may find it advantageous to uphold a shitty government or even a patriarchy if it means not having to go back to the state of nature (or as Andrea dworkin puts it in Right Wing Women, better to be a whore for one man than for every man).

(2) I think Suzanne Collins herself is either a cerebral structural thinker, or likes that style of thinking since she herself has been in the military, and as someone trained in screen writing for television, she’s also used to structure taking precedence sometimes over natural story flow. It’s probably why her writing has so much integrity and foresight as well very clearly available symbolism. She’s errs more on the side of a top down writer and so even the structure of the hunger games is as controlled as corio’s character. So if you like the style of writing, you may also like the protagonist who operates similarly (he’s literally a peacekeeper).

(3) as CS Lewis once said, in order to be bad, you have to be good at some things, right? Can’t really be evil if you can’t stick to a schedule, or some type of consistency. Coriolanus always had three priorities throughout the book and movie: control, himself, and Lucy, and they were constantly moving around and changing in rank or importance. People can admire that he likely did love Lucy in his own way, and that he was so clever and self disciplined, while not wholesale admiring his narcissism.

#tbosas spoilers#tbosas#the ballad of songbirds and snakes#ballad of songbirds and snakes#coriolanus snow#snow lands on top

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The first real conversation Katniss has with Peeta is when he tells her that he wants to die as himself, that he doesn't want the games to change him into something he's not, and that he wants to keep his identity and prove he's more than just a piece in their games because that's the only thing he has left to care about.

The first time we see Lucy Gray she sings a song that basically says that nothing they could take from her was worth keeping. "Can't take my past. Can't take my history... You can't take my charm. You can't take my health."

The capitol has taken everything from them both, but at the same time, they could never take away who they are.

They are both likeable charismatic and funny, with the kindest hearts, and incredibly loyal to the people they care about.

At the same time, everything they do before the games, and during is calculated. Lucy Gray singing a love song and winning the hearts of the capitol. Peeta confesses he's in love with his district partner, therefore cementing her identity as desirable. Both of them know how to sway people with words, how to charm people, and how to manipulate crowds. Neither of them has any problem doing so to keep themselves, and the people they love safe.

Lucy Gray's song The Old Therebefore, about learning how to love and live her life to the fullest before death, a final and calculated stroke in a last-ditch effort to save herself from the arena. This evokes enough emotion in the watchers to get them to rise to their feet and plead for her life alongside Snow.

Snow, watching the 74th and preparing for the 75th Hunger Games sees Lucy Gray in Katniss. A young girl, from the 12th district. Unafraid at the reaping. Selling a false love story, manipulating a boy who loves her in order to get out and supporting the revolution with the mockingjay as her symbol.

He threatens her family to get her to sell that she and Peeta are in love, to prevent the revolution, because obviously, she's pretending. He's had experience with a girl just like her before. He has no doubt that she has the acting ability to sell this story because clearly, she manipulated the first Hunger Games in her favor, the same way Lucy Gray manipulated him.

Watching the interviews for the 75th Hunger Games he realizes-

Katniss is just an impulsive girl, in a Mockingjay dress she didn't know about, made by someone who supports the revolution.

Peeta is a boy who has the ability to move people with just his words. He made Katniss desirable, he was the one who sold the love story, and he was the one to make their romance seem real. Katniss only started the revolution because she would rather risk dying with him than live without him. A concept President Snow was completely unfamiliar with. And it is with all these realizations crashing around him Peeta drops the baby bomb. He knows the baby's not real, and so does Snow. But it evokes enough emotion in the watchers to get them to rise to their feet and plead for the lives of the tributes.

Is it Lucy Gray or Peeta?

By the time Snow realizes he's made a mistake, it's too late.

Peeta is still charming and manipulating the capitol. Katniss is in love.

He goes up against a kindhearted boy expecting to beat Sejanus again, only to find out that it's Lucy Gray he's fighting; knowing he will never be able to escape their ghosts.

-from a conversation i had with @grandtyphoonpoetry breaking down every character in the hunger games.

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

Just wanted to add: the mockingjay PERFECTLY exemplifies the above too.

Jabberjays represent engineered order (also the Capitol) which Snow admires. Mockingbirds are wild nature (also the districts).

Snow is not a fan of mockingbirds, but they create the necessary contrast to the jabberjay and together, they create a clear boundary. What snow hates more than anything though are the mockingjays because they also represent the breakdown in division between carefully curated order and chaos. It’s why he’s uncomfortable with Dr. Gaul’s mutts as well. If this is true, it supports the above theory that Lucy doesn’t symbolize chaos so much as she symbolizes a breakdown in the binary of order/chaos. It’s why they repeat her last song and disorient snow.

Ironically, I was actually explaining all of this to my poor bf at the Michael’s parking lot when we pulled up behind someone with a thin blue line bumper sticker.

Arguments and symbolism in TBOSAS, or, why it couldn’t have ended any other way.

tldr: I think the biggest lesson from TBOSAS is that it’s less important to know what human nature really is (even if such a thing were possible) than it is to know what someone gains or loses from trying to convince you that humans inherently act one way or another.

Tswr:

It’s pretty clear that Coriolanus is, and it’s critical we say this as an individual, self important. This is a personality trait of his. He might have had it whether he was born during a war or peaceful democracy. But it’s also safe to say his personal experiences push him towards the belief that humans are inherently savage— which is the Hobbesian view and which has been historically used to justify totalitarian government since even a horrible government is better than a state of nature.

Sejanus is the foil. He represents Locke’s view on human nature which is that we aren’t all that bad, and that sometimes, disorganization and chaos is less bad than a totalitarian regime. I wasn’t surprised to see the m/m tags roll out between him and Coriolanus since there’s some obvious tension between their positions but they both share a common argument: BOTH claim to know what human nature “really” is.

So where does that leave Lucy? Or Rousseau? Or even the bigger takeaway?

In David Graebher’s last book, The Dawn of Everything, he is very careful to describe Rousseau’s social contract and, the dawn of human behavior. Where did the idea that humans were originally egalitarian come from? When did people decide to draw property lines and give themselves more than their neighbors? He uses anthropological evidence to cut through the centuries of argument between Locke and Hobbes to say that, maybe we don’t know, maybe it’s a bit of both.

Lucy Gray is NOT Sejanus, and from the very beginning she is shown to exist completely outside of their argument and even government as indigenous and part of a traveling band. That’s why she makes it a point to say she isn’t district, that’s why she moves in and out of Panem freely, it’s why we never get her POV, and why Coriolanus is constantly second guessing where he stands with her, or some of the deeper meanings of her music. *He doesn’t know her nature.*

And what does Dr. Gaul say? The type of government people need is derived from people’s nature. Coriolanus cannot control or overcome Lucy. Nothing she has “was ever worth keeping”. As an individual character, she is driven to self preservation which is the only leverage he ever has over her inside the games but quickly dissipates when she wins. We also know from later books where Katniss and Peeta are willing to commit suicide that even self preservation isn’t a consistent pillar of human nature either.

So what makes their romance so delicious? They’re drawn to each other because they quickly notice they’re both natural performers and they both need each other’s cooperation to succeed. And it’s no surprise that in a book all about human “nature” and who we authentically are theres also so much discussion about performance and anti-authenticity and why Coriolanus keeps bringing up the way Lucy Gray checks the mirror, dresses like a clown, performs, and stays in a literal monkey zoo. I think that’s why the zoo is so special for them is because it’s literally a place where nature meets performance. When animals are in a zoo, it’s manufactured nature and we know they will behave differently outside the bars. Similarly, when the humans are placed in the zoo, it’s manufactured performance with the assumption that they will soon act “naturally” (ie, self interested and evil) once placed in the hunger games.

I think this is where the cautionary tale for the reader becomes important and where Coriolanus let’s his need for power override his common sense: the hunger games are completely unnatural. They’re a continuation of the circus; the games are NOT humanity stripped bare because such a thing CANNOT exist. His problem initially is that he thinks “bare” human condition is what happens when humans are responding to injustice/crisis/war/poverty but I think he quickly realizes even this is bullshit since he adds a bunch of components to the games to make it more cinematic. He might at some point have thought everyone has an outer performance they cloak their internal “savage” nature with just like he does, just like the compact filled with poison, because he thinks people will do anything to get ahead, but I think that by the end he doesn’t even care about this. Its just another framework that services his ultimate quest for power at all costs.

So snow analyzes Lucy through the same lens he holds for himself but also realizes this doesn’t apply. He thinks she’s a singer and show woman with some interior nature he just cannot know. She’s a black box. She sings but even many of the songs just further the mystery of Lucy Gray who got lost in the snow. She tells him he knows the “ideal her, the real her” but maybe the real her is just whatever she is, or maybe she knew that this is the one thing he ever wanted from her and so she manipulates him with it— or maybe not. It doesn’t really matter to her.

So. If Snow always lands on top, but Lucy Gray exists in a framework where there is no top or bottom, he cannot ever control her. If a government must know its citizens’ nature to lead them, but Lucy Gray’s has no clear “nature” then he cannot control her either. So, he fabricated a story in his head about what she’s really like (Lucy Gray is no lamb). This story is NOT criticizing the idea that people have inherently evil nature— it is criticizing the compartmentalization of authentic and performative self. In other words, it’s a DECONSTRUCTION of the binary opposition elaborated by not only the compact, but the games themselves. This is super clear by the 74th games because by then, the games are clearly set up to have a performative phase with outfits and interviews, followed by the game itself where the competitors are at their most “base” selves. The carefully curated contrast between civility and chaos, or performance and authenticity, is what is supposed to scare people into thinking that the circus, or “authority” of gov’t is what keeps these elements in balance. Deconstructing this binary means admitting that we were always performing, and we were always being authentic, at the same time, continuously and always.

In the text, Snow is uneasy after the games end when he’s sent to 12 for several reasons but I think, whether he knows it or not, he’s most surprised that lucy acts the same as when he met her. She’s not much different from in the arena, and his frustrations when listening to her music or dealing with the reality of her simple country life read to me like he’s thinking: “why is she still doing this? There are no cameras here? Why is she still playing it up like this?”. He literally cannot wrap his mind around the fact that there are people whose very lives “are” performance and that they don’t separate themselves out like he does. He must also have realized that when they first developed their romance at the zoo that he characterized her incorrectly in thinking she was “on” and performing like him, and then he may never know if she meant anything by kissing him at all.

If snow had to acknowledge this was possible, that people do not have an internal and external self, then he would also have to acknowledge that people cannot be hiding raging self interest at all times which is policed by a government— then the world would have no need for him.

(The victor, like in any good story, is really Derrida)

So here’s the part that sucks. HOW do you even write fanfic without violating their personalities and making them entirely different characters? How does someone who enjoyed these characters get more than 2 hrs and 48 minutes or the og novel out of them when every decision is so clearly character driven? Either of them would have made the same choices in any universe together! And I think that’s what so maddening about this story for me and why I have reread the book so many times. Just like Snow says at the very end, not only is his rise to power inevitable, so is this story.

#tbosas#tbosas spoilers#the ballad of songbirds and snakes#ballad of songbirds and snakes#coriolanus snow#president snow#the hunger games

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arguments and symbolism in TBOSAS, or, why it couldn’t have ended any other way.

tldr: I think the biggest lesson from TBOSAS is that it’s less important to know what human nature really is (even if such a thing were possible) than it is to know what someone gains or loses from trying to convince you that humans inherently act one way or another.

Tswr:

It’s pretty clear that Coriolanus is, and it’s critical we say this as an individual, self important. This is a personality trait of his. He might have had it whether he was born during a war or peaceful democracy. But it’s also safe to say his personal experiences push him towards the belief that humans are inherently savage— which is the Hobbesian view and which has been historically used to justify totalitarian government since even a horrible government is better than a state of nature.

Sejanus is the foil. He represents Locke’s view on human nature which is that we aren’t all that bad, and that sometimes, disorganization and chaos is less bad than a totalitarian regime. I wasn’t surprised to see the m/m tags roll out between him and Coriolanus since there’s some obvious tension between their positions but they both share a common argument: BOTH claim to know what human nature “really” is.

So where does that leave Lucy? Or Rousseau? Or even the bigger takeaway?

In David Graebher’s last book, The Dawn of Everything, he is very careful to describe Rousseau’s social contract and, the dawn of human behavior. Where did the idea that humans were originally egalitarian come from? When did people decide to draw property lines and give themselves more than their neighbors? He uses anthropological evidence to cut through the centuries of argument between Locke and Hobbes to say that, maybe we don’t know, maybe it’s a bit of both.

Lucy Gray is NOT Sejanus, and from the very beginning she is shown to exist completely outside of their argument and even government as indigenous and part of a traveling band. That’s why she makes it a point to say she isn’t district, that’s why she moves in and out of Panem freely, it’s why we never get her POV, and why Coriolanus is constantly second guessing where he stands with her, or some of the deeper meanings of her music. *He doesn’t know her nature.*

And what does Dr. Gaul say? The type of government people need is derived from people’s nature. Coriolanus cannot control or overcome Lucy. Nothing she has “was ever worth keeping”. As an individual character, she is driven to self preservation which is the only leverage he ever has over her inside the games but quickly dissipates when she wins. We also know from later books where Katniss and Peeta are willing to commit suicide that even self preservation isn’t a consistent pillar of human nature either.

So what makes their romance so delicious? They’re drawn to each other because they quickly notice they’re both natural performers and they both need each other’s cooperation to succeed. And it’s no surprise that in a book all about human “nature” and who we authentically are theres also so much discussion about performance and anti-authenticity and why Coriolanus keeps bringing up the way Lucy Gray checks the mirror, dresses like a clown, performs, and stays in a literal monkey zoo. I think that’s why the zoo is so special for them is because it’s literally a place where nature meets performance. When animals are in a zoo, it’s manufactured nature and we know they will behave differently outside the bars. Similarly, when the humans are placed in the zoo, it’s manufactured performance with the assumption that they will soon act “naturally” (ie, self interested and evil) once placed in the hunger games.

I think this is where the cautionary tale for the reader becomes important and where Coriolanus let’s his need for power override his common sense: the hunger games are completely unnatural. They’re a continuation of the circus; the games are NOT humanity stripped bare because such a thing CANNOT exist. His problem initially is that he thinks “bare” human condition is what happens when humans are responding to injustice/crisis/war/poverty but I think he quickly realizes even this is bullshit since he adds a bunch of components to the games to make it more cinematic. He might at some point have thought everyone has an outer performance they cloak their internal “savage” nature with just like he does, just like the compact filled with poison, because he thinks people will do anything to get ahead, but I think that by the end he doesn’t even care about this. Its just another framework that services his ultimate quest for power at all costs.

So snow analyzes Lucy through the same lens he holds for himself but also realizes this doesn’t apply. He thinks she’s a singer and show woman with some interior nature he just cannot know. She’s a black box. She sings but even many of the songs just further the mystery of Lucy Gray who got lost in the snow. She tells him he knows the “ideal her, the real her” but maybe the real her is just whatever she is, or maybe she knew that this is the one thing he ever wanted from her and so she manipulates him with it— or maybe not. It doesn’t really matter to her.

So. If Snow always lands on top, but Lucy Gray exists in a framework where there is no top or bottom, he cannot ever control her. If a government must know its citizens’ nature to lead them, but Lucy Gray’s has no clear “nature” then he cannot control her either. So, he fabricated a story in his head about what she’s really like (Lucy Gray is no lamb). This story is NOT criticizing the idea that people have inherently evil nature— it is criticizing the compartmentalization of authentic and performative self. In other words, it’s a DECONSTRUCTION of the binary opposition elaborated by not only the compact, but the games themselves. This is super clear by the 74th games because by then, the games are clearly set up to have a performative phase with outfits and interviews, followed by the game itself where the competitors are at their most “base” selves. The carefully curated contrast between civility and chaos, or performance and authenticity, is what is supposed to scare people into thinking that the circus, or “authority” of gov’t is what keeps these elements in balance. Deconstructing this binary means admitting that we were always performing, and we were always being authentic, at the same time, continuously and always.

In the text, Snow is uneasy after the games end when he’s sent to 12 for several reasons but I think, whether he knows it or not, he’s most surprised that lucy acts the same as when he met her. She’s not much different from in the arena, and his frustrations when listening to her music or dealing with the reality of her simple country life read to me like he’s thinking: “why is she still doing this? There are no cameras here? Why is she still playing it up like this?”. He literally cannot wrap his mind around the fact that there are people whose very lives “are” performance and that they don’t separate themselves out like he does. He must also have realized that when they first developed their romance at the zoo that he characterized her incorrectly in thinking she was “on” and performing like him, and then he may never know if she meant anything by kissing him at all.

If snow had to acknowledge this was possible, that people do not have an internal and external self, then he would also have to acknowledge that people cannot be hiding raging self interest at all times which is policed by a government— then the world would have no need for him.

(The victor, like in any good story, is really Derrida)

So here’s the part that sucks. HOW do you even write fanfic without violating their personalities and making them entirely different characters? How does someone who enjoyed these characters get more than 2 hrs and 48 minutes or the og novel out of them when every decision is so clearly character driven? Either of them would have made the same choices in any universe together! And I think that’s what so maddening about this story for me and why I have reread the book so many times. Just like Snow says at the very end, not only is his rise to power inevitable, so is this story.

#coriolanus snow#tbosas#the ballad of songbirds and snakes#the hunger games#president snow#ballad of songbirds and snakes#tbosas spoilers

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

HANDS for any artist that needs, well, a hand! 🖐️ Reblog to encourage an artist to practice 👍

☆Get the full set of hands free here!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

You know how many people of color get tired watching films such as “12 years a slave” or movies which are obviously trauma porn? That clearly are there to confront you with reality? Why there is a desire for media which skips to the part where we have equal representation and rights?

I think most women, and certainly Greta Gerwig, are aware of the position women actually occupy in the world. (1) No one wants to see the Kens get tortured and raped, or actually abused— we really don’t need to (2) it doesn’t even make sense for the plot. the characters are based on the little girls who play with them and little girls don’t craft worlds that are an inverse of patriarchy because they’re not yet aware of all the way they’ll be hurt by it. The Barbie’s are benevolent or just flat out ignore the Kens because that’s how girls play with their dolls. (3) it’s ineffective for the message of the movie, if you want class solidarity which is far reaching, you can’t just quote andrea dworkin and show ken getting denied for a mortgage.

This movie is funny and light hearted enough to safely plant hope for women world wide— to show them a world where they could theoretically de center men from their lives. Not only that, its gender equality messages exist at multiple levels so that anyone should be able to walk out with something useful from the movie (like america ferrera’s speech wasn’t my personal jam, but it might be just what another women needed). It did ALL of this while scoring half a billion dollars in its first week of release under a female director— this is not discourse(TM), this movie is already female excellence incarnate.

So i just saw the Barbie movie

Visually, it was stunning, but the storyline was meh at best

Spoilers from this moment on

My biggest complaint is that the movie has a very surface level understanding of feminism and the patriarchy, or more specifically the problems inherent in a society where only one gender is allowed to be more than an accessory

Barbieland is a matriarchy, and at first it seems wonderful, they have a black president Barbie, they have an all-Barbie supreme court, their nobel prize winners and great scientists and doctors are all Barbies

Great, right? And it makes sense, an all-Barbie society would naturally be led by women.

Except it's not an all-Barbie society.

Which is where the film's view of a feminist utopia falls apart, because there's Midge, who lives on Barbie's street but never leaves her yard, there's Allan, who's literally the only one of his kind, and then there's the Kens.

The Kens don't have real jobs, Ryan Gosling's job is supposedly "beach," which does not mean lifeguard, there is a Ken who appears to be a lifeguard, but the water's fake so all he does is sit on the tower and use binoculars. Instead, every Ken has one responsibility: be Barbie's boyfriend.

Now in the real world, women weren't able to open a bank account on their own without a husband until 1974. We generally don't think of women having entered the workforce until the 40's in America, when the men went off to fight in the war effort. And even today, there's an implication that you're a failure of a woman if you can't get a partner.

The Kens don't have an identity outside of "Barbie's boyfriend" which leads Ryan Gosling's Ken to flounder from pretty much the moment we meet him because Barbie is clearly not interested in him. (She doesn't actually communicate this to him at all either until the very end of the movie) The fact that being called "sir" by a woman who was asking him what time it was translated in his mind as her seeing him as an authority figure is sad and kind of pathetic. So when he saw other men doing things that weren't connected to their partners, like driving trucks, drinking beers, and riding horses, it's not surprising that he equated those with having an identity of his own.

But herein lais my second major complaint with the movie: how Ken is radicalized.

Trucks, beer, and horses are not what makes someone do what Ken does. Possibly seeing a world where men are in charge would compel him to try to take over Barbieland, but it's specifically the way that he and the other kens objectify and mistreat the Barbies that felt very strange with what we were shown that he saw. I think if we'd seen him hear something like an Andrew Tate podcast or something it would make more sense, especially with how his basic desire is for Barbie to want to be with him the way he wants to be with her, as well as why the patriarchyhe brings back is so violent and how similar it is to real-world patriarchy.

Barbieland's matriarchy is not violent in its oppression of the Kens, its more that the Barbies don't see the Kens as being equal to them. Which is still oppression. It's arguably a more benign form, but it's still oppression.

So when the Barbies reinstate their matriarchy with no changes except for bringing Weird Barbie back into the fold again and giving the Kens the possibility of a minor court judge one day, it's really frustrating because the film is basically saying there that there were no problems with the original system, when clearly there were if Ken was able to radicalize all the other Kens in literally one day. It's saying that as long as women are in charge, everything is perfect.

The narrator even says "one day, the Kens might even have as much power as women do in the real world."

When so much of the cast and crew was talking about how this was a great feminist movie, I'm just disappointed by how surface level it actually was.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I would actually like to say— I think Sasha does add something valuable to the film.

She is literally the equivalent of an edgy teen girl. I WAS Sasha— I took high school debate and thought I was the first girl ever to discover nihilism, capitalism, and feminism. I thought I was doing something no one else was doing by being this grim, sardonic person. Things were very black and white for me and Barbie was emblematic of all of these problems we talked about in debate. Additionally, I felt I had push away my femininity to be taken seriously in debate.

The film is a coming of age film— loss of innocence, acknowledgement that reality is not just black or white…etc are part of it. Sasha is a lot like that teen still going through the idealistic part of growing up— and once you’re on the other side you realize that Barbie can have all of these reputations, whether that’s as a beauty standard or a good career model or capitalism or so on.

Margot’s barbie is complex, just like barbie the doll’s reputation, and what she means to people. Just like the film is, and just like us.

- Barbie Spoilers -

But really, Sasha was an annoying character. The majority of teenagers would think that a woman who looks like a life sized Barbie would be cool. While I do agree that teens these days do love calling people facists for literally anything the whole take on her character was not it.

The movie honestly would've been better if it was just about an overworked woman trying to reconnect with the happier times of her youth and finding her old Barbie doll in her attic or whatever

12 notes

·

View notes