Ai's new writeup blog (previously @digital-survivor for Digimon Survive and @4-roaring for Idolish Seven, now archived+privated). Basically this is where I dump my thoughts and musings.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

"Becoming as One" and the Themes of Harmony in Digimon Survive

Overanalyzing Aoi and Shuuji again, because this is my new hobby ever since I played Survive.

They share many parallels, both obvious and subtle, that I feel are often overlooked. One of the lesser-discussed similarities is how their corruption arcs culminate in “bio-merging” with their respective partnermon, a process where the human and partnermon become a single entity. Since both characters are Harmony-aligned, I believe it’s worth exploring how these instances of bio-merging relate to and represent the themes of Harmony. More under the cut.

TWs: discussions of self-loathing and suicidal thoughts

Given that the partnermons are meant to reflect their human partner’s true self, I find it somewhat ironic that in two out of the three instances of bio-merging in Survive, the result paradoxically embodies a loss of self. While it makes sense when you consider the Harmony kids’ common thread of seeking conformity, one might expect that merging with one’s true self would lead to the realization of true selfhood. Instead, these unifications become vehicles of self-erasure, where the former self is submerged by a new identity, as they are represented as dark evolutions that occur when the ideals of Harmony are taken to an extreme.

To get what I mean, let’s consider Kaito’s corruption arc. Symbolically, Kaito letting go of Dracumon by fusing Vamdemon (Dracumon) with Piemon can be seen as him discarding his conscience to further his selfish desires without any regard for others. This makes sense to most of us easily, because we’re consistently shown how Dracumon acts as Kaito’s restraint throughout the story — his “moral compass”, if you will. Without Dracumon, there’s no one who can keep Kaito in check anymore. So, the “death” of Dracumon being the metaphor for Kaito going morally bankrupt feels pretty intuitive, at least to me personally.

In contrast, I didn't find the symbolism in Shuuji’s and Aoi’s corruption arcs—particularly their fusion with their partners—as immediately intuitive, for the reasons I’ve outlined earlier. However, after mulling over their arcs a bit more, I’ve come to the realization how both of them becoming one with their respective partner can actually carry multifaceted symbolism that may not be immediately apparent. Also, the different nuances in how the themes of Harmony manifest in their arcs mean that the symbolism works a bit differently in each of their arcs too. Let me explain.

First off, we’ll look at Shuuji and Lopmon. Shuuji’s arc revolves around his struggle with self-acceptance. Through his father’s relentless expectations, he’s always made to feel inadequate, and in turn it drives him to constantly force himself into an imaginary mold that he doesn’t fit into. He does this by repressing his true feelings while trying to live up to (what he believes to be) his father’s idea of a perfect self. His very apparent hatred of Lopmon is mostly meant to represent his self-loathing, among many other things — in a way, Lopmon serves as a reminder for Shuuji that he hasn’t truly changed into the person that his father wants him to be. This is why Shuuji keeps trying to force Lopmon to change as well, even if it means cruelly pushing him beyond his limits.

The outcome of Shuuji’s arc depends on whether he comes to recognize his mistaken beliefs. If he fails to do so, Lopmon evolves into Wendimon and devours him. As this post has already described, this scene serves as a metaphor for Shuuji succumbing to the self-hatred that has been eating away at him from within, leading to a complete loss of self. Because, in both a figurative and literal sense, no trace of Shuuji’s former, “true” self remains—just as there’s nothing left of the Lopmon we once knew in Wendimon.

Most people believe that this is the moment where Shuuji finally dies, but I think that isn’t the case. In Survive, the lore states that a partnermon dies the moment their human dies. However, Wendimon doesn’t die right after he completely consumes Shuuji, and instead, he gains the ability to speak. Make of this what you will, but in my opinion, this gives a clue that Wendimon being alive after consuming Shuuji isn’t merely a narrative convenience to keep him around for the fight, and that Shuuji has actually been absorbed into Wendimon. In other words, Shuuji and Lopmon are finally unified in their suffering as Wendimon, with Wendimon’s monstrous form serving as a visual manifestation of both Shuuji and Lopmon’s new identity, warped beyond recognition even to themselves.

If you pay close attention to Wendimon’s speech, you’ll notice that he actually speaks with two voices — both Shuuji’s and Lopmon’s. It can be hard to tell since the voices are heavily filtered, but Shuuji’s voice has a slightly deeper pitch than Lopmon. Even if you can’t tell, the story hints at this detail by showing how the other kids and partnermons can distinguish between the voices when Wendimon speaks.

“IT HURRRTS… I’M SCAAARED… I DON’T WANNA DO THIIIS…” “WHAT’S… WRONG WITH ME? WHAT SHOULD I HAVE DONE…?”

I bring this up because it’s intriguing how Wendimon speaks in dual voices despite supposedly being a single entity. It’s as if the story is trying to convey that, even in their merged state, Shuuji and Lopmon aren’t truly reconciled — and it’s because Shuuji hasn’t silenced the part of himself that continues to question and doubt. To understand this, notice how Wendimon wails about two entirely different things: in Lopmon’s voice, he cries about how he doesn’t want to do any of this anymore, how he’s scared of this and how it hurts. Meanwhile, in Shuuji’s voice, he rants about not knowing what he should have done to make others happy (but especially to please his father, as I believe his words are primarily directed at his father) and wonders if it’s better for him to disappear if his existence is a nuisance to other people. While Lopmon continuously voices Shuuji’s true feelings that he buries deep inside, Shuuji himself remains fixated on seeking external validation and is concerned about what others think of him even at the expense of his own well-being.

To understand why Wendimon having dual voices is relevant to this discussion in the first place, let’s now turn our attention to Aoi and Labramon. Aoi’s character arc revolves around her desire for authority and proactiveness, which she struggles with because her self-consciousness constantly holds her back from taking actions. This is largely why Aoi and Labramon’s dynamic is vastly different from Shuuji and Lopmon’s relationship, because while Aoi also represses the side of her that Labramon displays — whether subconsciously or not — Labramon’s outspokenness instead embodies the part of Aoi that she wishes she could express more freely but is suppressed by her insecurity.

When Aoi merges with Labramon, the situation is slightly different from Shuuji’s experience, though it carries its own tragic implications: in an effort to save Aoi, Labramon sacrifices her own “self” to become the new force that sustains Aoi’s life. Perhaps because it’s also fueled by Aoi’s overwhelming guilt and frustration over her perceived powerlessness, the act leads them to bio-merge and dark-evolve into Plutomon.

While not entirely analogous, I think it’s fair to make a comparison between Plutomon and Wendimon. The game itself does this as well: upon seeing Aoi becomes Plutomon and kills Piemon, Kaito instantly makes a remark of Aoi becoming like Shuuji. In English, the line is worded as:

“Don’t tell me this is like with Shuuji… When he turned all evil!?”

However, in Japanese, the line is:

“まさか……シュウジのように……暗黒進化か!?” “Don’t tell me… she’s become like Shuuji… is it a dark evolution!?”

It’s interesting to me that Kaito immediately draws a parallel between her and Shuuji. And I have to emphasize that it’s specifically Shuuji, not Lopmon. I’m saying this because they all perceive Plutomon as Aoi instead of Labramon (the game emphasizes this too by having Plutomon’s name initially written as “Aoi?”), whereas we (as the players) tend to perceive Wendimon as Lopmon instead of Shuuji. See where I’m getting at here?

“Aoi, you say? No, I’ve cast off that weak persona.”

Now, unlike Wendimon, who retains both Shuuji’s and Lopmon’s voices, Plutomon speaks only with Aoi’s voice. One interpretation that we can draw is that, unlike Wendimon, the singular voice might represent Aoi and Labramon reaching a true level of mutual understanding and harmony where they don’t have to speak over each other in order to be heard. But I think there’s more to it: given that Labramon is consistently depicted in the story as voicing Aoi’s inner thoughts that she keeps holding back from expressing, I think this is meant to also symbolize her internal resolution where she no longer has the need to externalize her inner thoughts through Labramon, as she now fully embodies those thoughts herself. This might seem empowering at first, seeing how her newfound confidence seems to have conquered her lingering self-doubt that used to haunt her. However, on the other hand, the loss of Labramon’s separate voice means that Aoi has lost an external perspective. The implication is that Aoi is now entirely self-reliant, with no external check on her thoughts or actions. In other words, Aoi has lost the ability to see herself from an outside perspective that used to keep her grounded and connected to the world outside herself.

“Labramon agrees, from deep down inside me.”

(I put the screenshot above because I find it interesting — I think the fact that Aoi speaks on behalf of Labramon, rather than letting Labramon speak for herself, further supports the interpretation of Aoi having absorbed Labramon’s voice into her own, leaving no room for external input anymore.)

This ultimately leads Aoi to form a singular belief system, one that’s entirely shaped by her internal convictions. And it drives her into a dangerously inflexible mindset where any form of disagreement or differing perspective is perceived as a threat to her newly discovered harmony. In her mind now, the only way to ensure peace and unity is to eliminate the possibility of conflict altogether by merging everyone with their partnermon, creating a single, unified consciousness. And Aoi is absolutely resolute in this, because she has now isolated herself in her certainty by silencing other voices, becoming rigid and intolerant of any challenge to her worldview — one rooted in a distorted sense of harmony that results in a situation where disagreement is eradicated, not resolved.

Some of you might find it ironic that, despite supposedly embodying the corruption of harmony, Aoi (as Plutomon) seems to act more on her own selfish ideals rather than striving for true consensus, even if flawed. However, this makes sense when you contrast her motivation with Shuuji’s: while Shuuji is driven by external pressures and doesn’t necessarily “enjoy” conforming to others’ expectations, Aoi’s actions stem purely from her own self-imposed ideals. Aoi genuinely values social propriety and seeks to uphold it (as @digisurvive puts it, she’s the reason why the group is very hierarchical — she always makes sure that everyone follows the rules of conduct properly), so it’s natural that the themes of Harmony would manifest this way in her corruption arc. So, while Shuuji being absorbed into Wendimon through devouring represents the ultimate death of self, Aoi’s bio-merging with Labramon into Plutomon instead gives her an epiphany of her ideal version of “Harmony”—one she feels compelled to enforce on everyone.

#digimon survive#shibuya aoi#kayama shuuji#plutomon#wendimon#labramon#lopmon#digimon survive spoilers

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Something to add regarding my explanation of Guanyin, since it can lead to some misunderstandings: I have to clarify that while she’s also referred to as a “goddess” sometimes, Guanyin isn’t exactly considered a deity in the way gods are understood in many theistic religions. Precisely, she’s a bodhisattva, a figure who has attained a high level of enlightenment but chooses to remain in the cycle of birth and death (samsara) to help all sentient beings achieve liberation (nirvana). Sure, she’s venerated and often prayed to, but the veneration of Guanyin is more about seeking the embodiment of compassion than worshipping a divine being with power over the universe.

Aoi and Shuuji : Gendered Subtexts in Their Partners' Evolution Forms and How They Parallel Each Other

Believe it or not, this started out as me about to go on a long rant about the discourse on that Wukong game, since I feel like both sides are presenting their arguments in disingenuous manner regarding queer and feminist readings of Journey to the West (which involve discussions of Wukong and Guanyin as representations of feminist ideals and queer identities). However, I decided I wasn’t that invested in the discourse to write long paragraphs about it, so instead I chose to channel my energy to discuss something else you might not expect to have anything to do with this… which is Digimon Survive (lol). This writeup is going to discuss about Shuuji and Lopmon again, anyway (lol) — and yes, it’s going to be discussing about gender as well, and I’ll be doing it by drawing parallels with another pair, Aoi and Labramon.

A disclaimer before we start: as I’ll be discussing about the various interpretations of Guanyin (that, I feel, some might find sensitive — as they relate to Guanyin’s gender identity), I’d like to make it clear that I’m not a Buddhist nor was I raised a Buddhist by my family. However, I grew up in a culturally Chinese family, and have close relatives who are Buddhists that I’ve consulted on the depictions of Guanyin for the purpose of this writeup. I’ve also done extensive research about the figure online using various resources in English, Chinese, and Japanese. Take this information as you may (this also applies to other deities/figures I talk about in this writeup too, anyway). Heed this disclaimer here as well.

Another note: This writeup wasn’t as well-planned as my previous ones, so I apologize if it seems like I’m jumping from one point to another. It’s mostly me thinking out loud about more parallels I’ve discovered and the ideas I have about them. Just a heads up.

Some people have pointed out the parallels between Aoi and Shuuji, particularly in how their character arcs explore gendered themes. Both characters initially put on a facade that aligns with societal expectations of their gender roles, and each is paired with a Digimon/Kemonogami partner that jarringly contrasts with their outward persona — which makes sense, since the partnermons reflect the true self they both try to suppress. This post, in particular, also elaborates a bit further on the parallels by discussing about how their character arcs move in opposite directions. To reiterate: Aoi begins as the nurturing and permissive mother figure of the group, almost stereotypically feminine, but as the story progresses, she steps into a leadership role and embraces a more assertive personality, which isn’t necessarily associated with traditional femininity. Conversely, Shuuji starts off trying to fit into the rigid mold of an authoritative leader, believing this is what’s expected of him as the oldest boy in the group. However, he eventually must embrace his gentle and caring side to enable himself to reach his full potential, which challenges the initial idea presented that masculinity must always equate to emotional stoicism. Basically, by the story’s end (at least in the Truthful route), both characters take on roles more commonly associated with the opposite gender.

You might think the gendered themes of their character arcs end just there, but if you look into the evolutions of Labramon and Lopmon, you’ll uncover even more layers of gendered subtext — undertones that, while likely unintended, are intriguing to explore. It’s something that seems to have gone largely unnoticed, so that’s exactly what I’ll write about now. Hopefully this can offer another interesting perspective to their character arcs.

Let’s start with Labramon, as the subtexts in her evolutions feel less subtle to me. From the game mechanics alone, initially, Labramon functions primarily as a support unit, equipped with a healing skill that aligns with stereotypical feminine roles of care and nurturing. However, as she evolves, I’d say this role shifts rather significantly. In her evolution forms (Dobermon, Cerberumon, Anubimon, and even Plutomon), Labramon transitions into a powerful offensive unit, taking on a more aggressive and assertive role that contrasts with her earlier, more traditionally feminine characterization.

What’s also particularly striking is the design and appearance of these evolutions. Dobermon, Cerberumon, and Plutomon all adopt distinctly masculine aesthetics, characterized by strong, fierce, and intimidating designs that align with traditional male archetypes. They also shed the cutesy appearance that Labramon initially has, replacing it with a color palette dominated by black and deep shadowy tones on top of very sharp silhouettes, which starkly contrast with Labramon’s original softer look. It almost feels as though her evolutions discard femininity to embrace more conventionally masculine traits like strength, aggression, and dominance. The game even alludes to this by showing how taken aback Aoi is when she first sees Cerberumon’s intimidating appearance.

Not only that, both Labramon’s two ultimate forms, Anubimon and Plutomon, are based on male deities. Anubis, the god of afterlife in ancient Egyptian religion, is strictly male in his depiction as a man with a jackal head. Even the etymology of his name reinforces this — the name “Anubis” comes from the ancient Egyptian word “Inpw”, which is masculine in grammatical gender. In ancient Egyptian language, words had gender, and the suffix “-w” typically indicated a masculine form (hypothetically speaking, the female form of “Inpw” would have been “Inpwt”). Additionally, Anubis has always been depicted with male attributes and roles in Egyptian mythology, such as being a protector of tombs, which was customarily a male-associated role in ancient Egypt.

Pluto is also consistently depicted as male in the original Greek mythology. The name “Pluto” (Plūtō) itself is the Latinized version of the Greek “Plouton”, which is a euphemism for the underworld god Hades, who is also strictly male. What’s even more interesting to note is that Pluto is the Roman counterpart of Dis Pater (Rex Infernus), whose name is commonly interpreted as “Rich Father” and may be a direct translation of Plouton. Note how the meaning of the name emphasizes the male aspect of the deity, as the title “father” is already inherently masculine.

Despite all of that, though, one thing I want to also note here is that Labramon and her evolutions consistently maintain a feminine speech pattern that’s largely shared by Aoi. An explanation for context: in Japanese, you generally can tell the gender identity of the speaker from their speech pattern (i.e., the way a male individual speaks and a female individual speaks are pretty distinct). I find this especially interesting, because it shows that you’re meant to take Labramon and her evolutions as female despite the traditionally “male” depictions.

(Sure, you might argue that this is just another instance of Digimon taking liberties with gender depiction, as they did with Garudamon in Adventure. However, I still find it intriguing to note that among the female cast, Aoi is the only character whose partner’s evolutions are consistently gendered as “male” within the Digimon franchise.)

Let’s move on to Lopmon and his evolutions. While Lopmon doesn’t undergo the same dramatic shifts in appearance the way Labramon does, he does give off a somewhat feminine vibe with how cute and very “pink” (for the lack of a better word) he looks. This has led to some mistaking Lopmon as female, even though his speech pattern closely resembles Shuuji’s distinctly male speech pattern (this is a similar case to Aoi and Labramon anyway, where they share similar speech patterns with each other). Aside from that, there is also still a gendered theming present in his evolutions. In particular, two of his evolutions, Turuiemon and Andiramon, feature genderqueer elements in their origins.

As I mentioned in my previous writeup, Turuiemon is based on Tu’er Ye (Tù’eryé/兔兒爺), the rabbit deity entrusted with saving the people from a plague. According to the legend, Tu’er Ye needed to borrow clothes to wear in order to gain the trust of the people. What I didn’t mention, however, is that Tu’er Ye also had a female counterpart called Tu’er Nainai (Tù’ernǎinai/兔兒奶奶). While these two figures might seem distinct, they could actually be one and the same deity. In some versions of the legend, Tu’er Ye changed appearance depending on the clothing donated to him by the people he helped, implying that Tu’er Nainai could simply be a cross-dressing Tu’er Ye. In short, Tu’er Ye can be interpreted as genderqueer due to the fluidity of his gender presentation in these legends.

The genderqueer theme becomes even more prominent in Antila, the figure upon which Andiramon is based. Antila (Ānd��luò/安底羅) is one of the Twelve Heavenly Generals serving Bhaisajyaguru (the Medicine Buddha). Although Antila is strictly depicted as male and isn’t necessarily genderqueer in the original legend, he takes on a genderqueer interpretation through his depiction in Japanese religious syncretism of Buddhism and Shinto (shinbutsu/kamihotoke/神仏): Through a concept known as honji-suijaku (本地垂迹), where Buddhas and bodhisattvas serve as the true forms (honji/本地) that have worldly manifestations (suijaku/垂迹) as Shinto kami (神), it is said that Antila was the worldly manifestation of the bodhisattva Guanyin (i.e., Guanyin is the honji of Antila, and Antila is the suijaku of Guanyin). Guanyin as a figure is primarily depicted as female-presenting. However, I should note that the nuances of Guanyin’s gender are complex, so I’ll address them in the next paragraph.

For starters: Guanyin (Guānyīn/Kannon/觀音) is the bodhisattva of compassion. As a bodhisattva, she’s a Buddhist figure, but in East Asian and Southeast Asian folk religions, she’s also sometimes known as the Goddess of Mercy. While some Buddhist schools in East and Southeast Asia recognize Guanyin as a genderless or androgynous entity, she’s consistently depicted to be female-presenting, so as a result, East and Southeast Asians commonly refer to her as “Mother Guanyin” or “Goddess Guanyin”. However, this hasn’t always been the case throughout history, as there was a time long ago when Guanyin was depicted as a male. You see, Guanyin is essentially the same figure as Avalokitasvara (also written as Avalokiteśvara), originally depicted as male in India. He was initially depicted as male in China as well, where East Asian Buddhism first originates. However, seeing that the traits the bodhisattva had (e.g., compassionate, merciful, and nurturing) were seen as conventionally feminine by Chinese people, eventually the depiction of Guanyin as female took over. This change was so profound that by the time Buddhism spread further into East and Southeast Asia, the female depiction of Guanyin became the dominant one, solidifying her status as a “female” divinity instead of a “male” one. So, it’s safe to say that in the case of Guanyin as the true form of Antila, the intention is for her to be female, despite Antila being a male himself.

(Kind of a tangent: I don’t necessarily disagree with trans readings of Guanyin, whether in relation to her being Antila’s true form or the historical nuances of her gender depictions. I believe it’s a completely valid interpretation, to say the least. However, I must note that this perspective isn’t universally accepted — at least not among the Buddhists I know personally — so it’s important to approach this argument carefully. But anyway, I digress.)

I don’t have much to say about Cherubimon, as he is based on cherubim, who aren’t strictly defined as male or female, as far as I know. However, I personally find that Cherubimon’s appearance carries a distinctly feminine vibe, primarily through the character design and symbolic elements. I mean, Cherubimon features a softer, more rounded form, with large, expressive eyes that convey a sense of gentleness and add some cute factors. The pastel color palette, often dominated by shades of pink, further enhances this somewhat feminine quality. Additionally, his demeanor and role as a guardian figure align with traits typically associated with femininity, such as nurturing and protective instincts. I think it’s fair to say that the combination of these visual and thematic elements gives Cherubimon a feminine presence that contrasts with the more aggressive or imposing designs of most other ultimate level Digimon (including Labramon’s ultimate forms).

Interestingly, unlike Labramon’s evolutions, Lopmon’s evolutions don’t always retain Lopmon’s masculine speech pattern. Specifically, Andiramon and Cherubimon adopt more neutral speech patterns that aren’t distinctly masculine or feminine. I believe this is intended to represent both Andiramon and Cherubimon as more mature forms of Lopmon, with speech patterns that convey a sense of regality and dignity. Given the lore in Survive, where Digimon/Kemonogami are seen as the true selves of their human partners, it’s reasonable to still interpret both Andiramon and Cherubimon as male within the context of the game.

In addition to the individual subtexts, it’s also noteworthy to see how Labramon’s and Lopmon’s evolution lines as a whole reflect contrasting archetypes that align with traditional gender roles. As Labramon evolves into forms like Anubimon and Plutomon, she embodies a theme of judgment and authority, taking on the traditionally masculine role of one who wields power, dispenses justice, and determines the fates of others. On the other hand, Lopmon’s true evolution line (Turuiemon, Andiramon, and Cherubimon) centers around the theme of a guardian deity, which carries more feminine connotations such as care, compassion, and protection. I just think the whole contrast is worth pointing out, considering it aligns very well with the overall gendered undertones present in Aoi and Shuuji’s respective character arcs.

To end this writeup, I just want to reiterate once again: While these gendered subtexts might not be immediately apparent or universally acknowledged, I still think they provide additional depth to the narrative. They also offer a fascinating lens through which you can further explore both Aoi and Shuuji, beyond the much more obvious aspects of their arcs.

P.S. Another parallel I noticed in their evolution lines that I don’t know how to make sense of, but still find interesting (even if it might be coincidental): Labramon’s underworld theme versus Lopmon’s celestial theme. I find these contrasting themes intriguing as well, but I’m not sure how they fit into Aoi’s and Shuuji’s arcs. Any thoughts on this? Also feel free to add if you notice any else from Labramon and Lopmon!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aoi and Shuuji : Gendered Subtexts in Their Partners' Evolution Forms and How They Parallel Each Other

Believe it or not, this started out as me about to go on a long rant about the discourse on that Wukong game, since I feel like both sides are presenting their arguments in disingenuous manner regarding queer and feminist readings of Journey to the West (which involve discussions of Wukong and Guanyin as representations of feminist ideals and queer identities). However, I decided I wasn’t that invested in the discourse to write long paragraphs about it, so instead I chose to channel my energy to discuss something else you might not expect to have anything to do with this… which is Digimon Survive (lol). This writeup is going to discuss about Shuuji and Lopmon again, anyway (lol) — and yes, it’s going to be discussing about gender as well, and I’ll be doing it by drawing parallels with another pair, Aoi and Labramon.

A disclaimer before we start: as I’ll be discussing about the various interpretations of Guanyin (that, I feel, some might find sensitive — as they relate to Guanyin’s gender identity), I’d like to make it clear that I’m not a Buddhist nor was I raised a Buddhist by my family. However, I grew up in a culturally Chinese family, and have close relatives who are Buddhists that I’ve consulted on the depictions of Guanyin for the purpose of this writeup. I’ve also done extensive research about the figure online using various resources in English, Chinese, and Japanese. Take this information as you may (this also applies to other deities/figures I talk about in this writeup too, anyway). Heed this disclaimer here as well.

Another note: This writeup wasn’t as well-planned as my previous ones, so I apologize if it seems like I’m jumping from one point to another. It’s mostly me thinking out loud about more parallels I’ve discovered and the ideas I have about them. Just a heads up.

Some people have pointed out the parallels between Aoi and Shuuji, particularly in how their character arcs explore gendered themes. Both characters initially put on a facade that aligns with societal expectations of their gender roles, and each is paired with a Digimon/Kemonogami partner that jarringly contrasts with their outward persona — which makes sense, since the partnermons reflect the true self they both try to suppress. This post, in particular, also elaborates a bit further on the parallels by discussing about how their character arcs move in opposite directions. To reiterate: Aoi begins as the nurturing and permissive mother figure of the group, almost stereotypically feminine, but as the story progresses, she steps into a leadership role and embraces a more assertive personality, which isn’t necessarily associated with traditional femininity. Conversely, Shuuji starts off trying to fit into the rigid mold of an authoritative leader, believing this is what’s expected of him as the oldest boy in the group. However, he eventually must embrace his gentle and caring side to enable himself to reach his full potential, which challenges the initial idea presented that masculinity must always equate to emotional stoicism. Basically, by the story’s end (at least in the Truthful route), both characters take on roles more commonly associated with the opposite gender.

You might think the gendered themes of their character arcs end just there, but if you look into the evolutions of Labramon and Lopmon, you’ll uncover even more layers of gendered subtext — undertones that, while likely unintended, are intriguing to explore. It’s something that seems to have gone largely unnoticed, so that’s exactly what I’ll write about now. Hopefully this can offer another interesting perspective to their character arcs.

Let’s start with Labramon, as the subtexts in her evolutions feel less subtle to me. From the game mechanics alone, initially, Labramon functions primarily as a support unit, equipped with a healing skill that aligns with stereotypical feminine roles of care and nurturing. However, as she evolves, I’d say this role shifts rather significantly. In her evolution forms (Dobermon, Cerberumon, Anubimon, and even Plutomon), Labramon transitions into a powerful offensive unit, taking on a more aggressive and assertive role that contrasts with her earlier, more traditionally feminine characterization.

What’s also particularly striking is the design and appearance of these evolutions. Dobermon, Cerberumon, and Plutomon all adopt distinctly masculine aesthetics, characterized by strong, fierce, and intimidating designs that align with traditional male archetypes. They also shed the cutesy appearance that Labramon initially has, replacing it with a color palette dominated by black and deep shadowy tones on top of very sharp silhouettes, which starkly contrast with Labramon’s original softer look. It almost feels as though her evolutions discard femininity to embrace more conventionally masculine traits like strength, aggression, and dominance. The game even alludes to this by showing how taken aback Aoi is when she first sees Cerberumon’s intimidating appearance.

Not only that, both Labramon’s two ultimate forms, Anubimon and Plutomon, are based on male deities. Anubis, the god of afterlife in ancient Egyptian religion, is strictly male in his depiction as a man with a jackal head. Even the etymology of his name reinforces this — the name “Anubis” comes from the ancient Egyptian word “Inpw”, which is masculine in grammatical gender. In ancient Egyptian language, words had gender, and the suffix “-w” typically indicated a masculine form (hypothetically speaking, the female form of “Inpw” would have been “Inpwt”). Additionally, Anubis has always been depicted with male attributes and roles in Egyptian mythology, such as being a protector of tombs, which was customarily a male-associated role in ancient Egypt.

Pluto is also consistently depicted as male in the original Greek mythology. The name “Pluto” (Plūtō) itself is the Latinized version of the Greek “Plouton”, which is a euphemism for the underworld god Hades, who is also strictly male. What’s even more interesting to note is that Pluto is the Roman counterpart of Dis Pater (Rex Infernus), whose name is commonly interpreted as “Rich Father” and may be a direct translation of Plouton. Note how the meaning of the name emphasizes the male aspect of the deity, as the title “father” is already inherently masculine.

Despite all of that, though, one thing I want to also note here is that Labramon and her evolutions consistently maintain a feminine speech pattern that’s largely shared by Aoi. An explanation for context: in Japanese, you generally can tell the gender identity of the speaker from their speech pattern (i.e., the way a male individual speaks and a female individual speaks are pretty distinct). I find this especially interesting, because it shows that you’re meant to take Labramon and her evolutions as female despite the traditionally “male” depictions.

(Sure, you might argue that this is just another instance of Digimon taking liberties with gender depiction, as they did with Garudamon in Adventure. However, I still find it intriguing to note that among the female cast, Aoi is the only character whose partner’s evolutions are consistently gendered as “male” within the Digimon franchise.)

Let’s move on to Lopmon and his evolutions. While Lopmon doesn’t undergo the same dramatic shifts in appearance the way Labramon does, he does give off a somewhat feminine vibe with how cute and very “pink” (for the lack of a better word) he looks. This has led to some mistaking Lopmon as female, even though his speech pattern closely resembles Shuuji’s distinctly male speech pattern (this is a similar case to Aoi and Labramon anyway, where they share similar speech patterns with each other). Aside from that, there is also still a gendered theming present in his evolutions. In particular, two of his evolutions, Turuiemon and Andiramon, feature genderqueer elements in their origins.

As I mentioned in my previous writeup, Turuiemon is based on Tu’er Ye (Tù’eryé/兔兒爺), the rabbit deity entrusted with saving the people from a plague. According to the legend, Tu’er Ye needed to borrow clothes to wear in order to gain the trust of the people. What I didn’t mention, however, is that Tu’er Ye also had a female counterpart called Tu’er Nainai (Tù’ernǎinai/兔兒奶奶). While these two figures might seem distinct, they could actually be one and the same deity. In some versions of the legend, Tu’er Ye changed appearance depending on the clothing donated to him by the people he helped, implying that Tu’er Nainai could simply be a cross-dressing Tu’er Ye. In short, Tu’er Ye can be interpreted as genderqueer due to the fluidity of his gender presentation in these legends.

The genderqueer theme becomes even more prominent in Antila, the figure upon which Andiramon is based. Antila (Āndǐluò/安底羅) is one of the Twelve Heavenly Generals serving Bhaisajyaguru (the Medicine Buddha). Although Antila is strictly depicted as male and isn’t necessarily genderqueer in the original legend, he takes on a genderqueer interpretation through his depiction in Japanese religious syncretism of Buddhism and Shinto (shinbutsu/kamihotoke/神仏): Through a concept known as honji-suijaku (本地垂迹), where Buddhas and bodhisattvas serve as the true forms (honji/本地) that have worldly manifestations (suijaku/垂迹) as Shinto kami (神), it is said that Antila was the worldly manifestation of the bodhisattva Guanyin (i.e., Guanyin is the honji of Antila, and Antila is the suijaku of Guanyin). Guanyin as a figure is primarily depicted as female-presenting. However, I should note that the nuances of Guanyin’s gender are complex, so I’ll address them in the next paragraph.

For starters: Guanyin (Guānyīn/Kannon/觀音) is the bodhisattva of compassion. As a bodhisattva, she’s a Buddhist figure, but in East Asian and Southeast Asian folk religions, she’s also sometimes known as the Goddess of Mercy. While some Buddhist schools in East and Southeast Asia recognize Guanyin as a genderless or androgynous entity, she’s consistently depicted to be female-presenting, so as a result, East and Southeast Asians commonly refer to her as “Mother Guanyin” or “Goddess Guanyin”. However, this hasn’t always been the case throughout history, as there was a time long ago when Guanyin was depicted as a male. You see, Guanyin is essentially the same figure as Avalokitasvara (also written as Avalokiteśvara), originally depicted as male in India. He was initially depicted as male in China as well, where East Asian Buddhism first originates. However, seeing that the traits the bodhisattva had (e.g., compassionate, merciful, and nurturing) were seen as conventionally feminine by Chinese people, eventually the depiction of Guanyin as female took over. This change was so profound that by the time Buddhism spread further into East and Southeast Asia, the female depiction of Guanyin became the dominant one, solidifying her status as a “female” divinity instead of a “male” one. So, it’s safe to say that in the case of Guanyin as the true form of Antila, the intention is for her to be female, despite Antila being a male himself.

(Kind of a tangent: I don’t necessarily disagree with trans readings of Guanyin, whether in relation to her being Antila’s true form or the historical nuances of her gender depictions. I believe it’s a completely valid interpretation, to say the least. However, I must note that this perspective isn’t universally accepted — at least not among the Buddhists I know personally — so it’s important to approach this argument carefully. But anyway, I digress.)

I don’t have much to say about Cherubimon, as he is based on cherubim, who aren’t strictly defined as male or female, as far as I know. However, I personally find that Cherubimon’s appearance carries a distinctly feminine vibe, primarily through the character design and symbolic elements. I mean, Cherubimon features a softer, more rounded form, with large, expressive eyes that convey a sense of gentleness and add some cute factors. The pastel color palette, often dominated by shades of pink, further enhances this somewhat feminine quality. Additionally, his demeanor and role as a guardian figure align with traits typically associated with femininity, such as nurturing and protective instincts. I think it’s fair to say that the combination of these visual and thematic elements gives Cherubimon a feminine presence that contrasts with the more aggressive or imposing designs of most other ultimate level Digimon (including Labramon’s ultimate forms).

Interestingly, unlike Labramon’s evolutions, Lopmon’s evolutions don’t always retain Lopmon’s masculine speech pattern. Specifically, Andiramon and Cherubimon adopt more neutral speech patterns that aren’t distinctly masculine or feminine. I believe this is intended to represent both Andiramon and Cherubimon as more mature forms of Lopmon, with speech patterns that convey a sense of regality and dignity. Given the lore in Survive, where Digimon/Kemonogami are seen as the true selves of their human partners, it’s reasonable to still interpret both Andiramon and Cherubimon as male within the context of the game.

In addition to the individual subtexts, it’s also noteworthy to see how Labramon’s and Lopmon’s evolution lines as a whole reflect contrasting archetypes that align with traditional gender roles. As Labramon evolves into forms like Anubimon and Plutomon, she embodies a theme of judgment and authority, taking on the traditionally masculine role of one who wields power, dispenses justice, and determines the fates of others. On the other hand, Lopmon’s true evolution line (Turuiemon, Andiramon, and Cherubimon) centers around the theme of a guardian deity, which carries more feminine connotations such as care, compassion, and protection. I just think the whole contrast is worth pointing out, considering it aligns very well with the overall gendered undertones present in Aoi and Shuuji’s respective character arcs.

To end this writeup, I just want to reiterate once again: While these gendered subtexts might not be immediately apparent or universally acknowledged, I still think they provide additional depth to the narrative. They also offer a fascinating lens through which you can further explore both Aoi and Shuuji, beyond the much more obvious aspects of their arcs.

P.S. Another parallel I noticed in their evolution lines that I don’t know how to make sense of, but still find interesting (even if it might be coincidental): Labramon’s underworld theme versus Lopmon’s celestial theme. I find these contrasting themes intriguing as well, but I’m not sure how they fit into Aoi’s and Shuuji’s arcs. Any thoughts on this? Also feel free to add if you notice any else from Labramon and Lopmon!

#digimon survive#shibuya aoi#kayama shuuji#labramon#lopmon#dobermon#cerberumon#anubimon#plutomon#turuiemon#andiramon#cherubimon

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wendimon vs. Turuiemon: Mythological Explanations and Contrasting Parallels in Digimon Survive

This is a rewrite of a writeup I previously posted on my old archived Digimon Survive blog, @digital-survivor

Initially inspired by this post by @digisurvive on the mythological explanations for some of the kids’ partners, out of curiosity I decided to check if there’s anything interesting about Lopmon’s evolutions that I could possibly relate back to their roles in Survive (especially in regards to Shuuji as Lopmon’s partner). What I found turned out to be much more interesting than I anticipated, because it seems very likely that they intentionally incorporated elements from the original mythologies, particularly for Wendimon and Turuiemon — both of whom are Lopmon’s adult forms — even going so far as to draw parallels between them. More of it under the cut.

TWs: mentions of suicide and self-harm

At first glance, it might seem that Wendimon and Turuiemon have no connection at all, given that they originate from two vastly different cultures with no geographical ties. Wendimon is based on Wendigo from Algonquian folklore (primarily among Indigenous tribes in North America), while Turuiemon is based on Tu’er Ye (Tù’eryé/兔兒爺, literally “Lord Leveret”) from a Chinese folk religion in Beijing. On top of that, Digimon as a franchise itself rarely makes their connection clear beyond Wendimon and Turuiemon being the default adult forms of Lopmon. Despite all of that, there’s actually one theme that they do have in common: they both make their appearance during times of crisis. And yet, they both have starkly contrasting roles in their respective mythology.

Let’s start with Wendigo. Wendigo is told to be an evil spirit that emerges during the harshest of cold winters, when resources are scarce and survival becomes increasingly difficult. It preys on those who succumb to desperation and greed by possessing them and turning them into cannibals. Once possessed by Wendigo, the individual is cursed with an insatiable hunger — no matter how much they consume, they will forever remain emaciated and never feel full.

We can already see several references that Survive makes to the actual Wendigo mythology, the most obvious being Wendimon’s act of devouring Shuuji when he finally succumbs to insanity and desperation, which references Wendigo’s association with cannibalism. Many interpret this scene as a representation of Shuuji’s final surrender to his self-harm tendencies (in short, suicide) — and they aren’t wrong at all, but we can go a bit further by drawing more symbolism from the Wendigo myth: Shuuji is trapped in a self-destructive spiral driven by his constant need for external validation and his unfulfilled craving for approval, particularly from his father. This craving can be seen as a form of greed — not for material wealth perhaps, but for affirmation from others. In the same way that Wendigo’s victims are possessed for their greed and cursed with an insatiable hunger that leads to their ruin, Shuuji’s relentless yet fruitless pursuit of recognition forces him to repress his true feelings, and you can say this leads to his loss of self and eventually his demise, where he is metaphorically — and then quite literally — consumed by his own desperation. It’s also fitting that Lopmon evolves into Wendimon when Shuuji is at his lowest and very much cornered with no choice but to resort to desperate measures, which mirrors how Wendigo only appears during the coldest winters, when both despair and survival instincts are at their peak.

Let’s contrast that with Tu’er Ye, Turuiemon’s namesake. According to Chinese mythology, Tu’er Ye is also known as Yutu (Yùtù/玉兔, literally “Jade Rabbit”), the rabbit on the moon who pounds the elixir of life. Legend says that, once upon a time, he was sent by the Moon Goddess Chang’e (Cháng’é/嫦娥) to eradicate a plague on the land. The people of the land were initially distrustful of Tu’er Ye, seeing that his fur was white and white symbolized death in Chinese culture. However, this didn’t stop Tu’er Ye from saving them — he visited a nearby temple to borrow some clothes that he could wear to cover his white fur. After that, the people welcomed him, and Tu’er Ye successfully saved them from the plague. Ever since then, the people have been revering him as a symbol of protection. He is viewed as a guardian figure, especially for children, and is celebrated during festivals for his role in ensuring health and safety.

Even beyond Survive, the broader Digimon lore references Tu’er Ye through Turuiemon’s profile: Turuiemon is described as a Digimon that hunts down viruses that exploit e-mail, much like how Tu’er Ye’s mission is to eradicate the plague. Survive, however, takes this a step further by contrasting Turuiemon’s role in the story with Wendimon’s: While their evolution scenes take place during the exact same point in the story (that is, the peak of Shuuji’s mental breakdown), unlike Wendimon, Turuiemon appears to save him from a devastating situation, akin to how Tu’er Ye arrived to heal the people from the plague. Additionally, just as Tu’er Ye was initially distrusted by the people and could only rescue them after he gained their trust, Lopmon’s evolution into Turuiemon is only triggered when Shuuji finally places his trust in Lopmon (which in turn also symbolizes his willingness to accept himself for who he is). In contrast to Wendimon, whose appearance causes Shuuji’s death, Turuiemon sustains his life — which is very apt considering that Tu’er Ye is known for pounding the elixir of life, like mentioned earlier.

Aside from their mythological references, you can still draw more interesting parallels between Wendimon and Turuiemon from the story alone to see how they’re opposite of each other. Wendimon has an intimidating appearance and strength which gives Shuuji the impression that he has finally gained the upper hand after feeling weak for so long. However, this strength is deceptive — it isn’t born out of genuine growth, but instead out of Shuuji pushing Lopmon (and himself) beyond his limits. His obstinacy in this is fueled by the belief that the pain will help Lopmon grow stronger, just as his father’s harsh upbringing has forged him into the person he is today. It isn’t wrong to say that Lopmon does grow stronger from it by turning into Wendimon, but Wendimon’s strength is so destructive that it literally destroys Shuuji.

On the other hand, Turuiemon, while not exactly what you would picture as physically strong and imposing, only evolves once Shuuji finally adopts a healthier mindset — one of self-acceptance, most importantly. Sure, he doesn’t look that much more powerful than Lopmon, with his size only growing a little from his child form. However, it’s surprisingly this form of a more balanced strength that truly protects and saves Shuuji instead. It sends a message that I personally find very heartwarming — that real strength isn’t always about how much force you can exert, and that embracing who you are, rather than trying to force yourself into a mold that you don’t fit, is what leads to true and lasting strength to face adversity.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Cherubimon's evolution

One thing that people often don’t realize about Shuuji, despite it being fairly obvious from the beginning of the game, is how easily influenced he is by those around him. Although he seems stubborn on the outside (at least initially), he’s actually quick to yield to external pressure and bend to others’ wills. You could argue that, initially, he only kept giving in because he kept getting outnumbered. However, this tendency to relent to others is still apparent even in the Truthful route, where he’s no longer pressured by numbers the way he was during the beginning. For instance, when he suggested moving in order from the shrine with the strongest barrier, Aoi objected, insisting they should start with the weakest one instead, and they ended up following Aoi’s suggestion. This shows that he hasn’t fully shaken his habit of giving in to others even when he’s outgrown his other early game traits.

Part of why I think this behavior remains in Shuuji is because of the way he was raised by his father. While it’s true that Shuuji — very much like Aoi — has a strong sense of responsibility, I believe this sense duty also comes from his need to meet the expectations others have of him. His urge to fulfill these expectations seems to be driven by a desire to be accepted, as his father has made him believe that living up to these expectations is the only way to gain approval. In short, he constantly seeks external validation by repressing how he truly feels and following through what other wants.

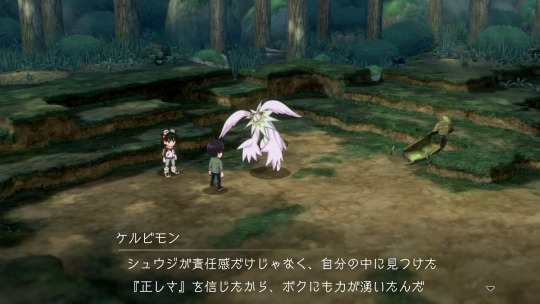

Cherubimon’s evolution scenario seems to address this persistent trait of his and attempts to make him grow out of it even if just a little. Due to the simplistic scenario presented in it (much like any other affinity-based evolution scene in Survive), perhaps not many notice it’s meant for that. However, ever since the first time I watched it play out, I’ve been intrigued by how this line by Cherubimon is worded:

“シュウジが責任感だけじゃなく、自分の中に見つけた『正しさ』を信じたから、ボクにも力が湧いたんだ”

This line (very literally) translates to “I was able to find strength because you (Shuuji) didn’t just rely on your sense of responsibility; you also believed in the ‘rightness’ you found within yourself.” Something to note is that I couldn’t quite come up with an appropriate word to translate “正しさ”, but we’ll get back to this later. English localization has it translated to “Believing not only in your duty, but in your own righteousness, you filled me with strength,” which isn’t wrong per se (it’s correct and it flows more naturally than the very literal translation I’ve come up with, in fact), but translating “正しさ” as “righteousness” in this context doesn’t really click in my opinion. Let me finally explain why.

While translating “正しさ” as “righteousness” isn’t necessarily wrong, “righteousness” often has a stronger moral or ethical connotation, implying a judgment of moral superiority or adherence to a strict set of principles. For me, this feels too heavy or “formal” in the context where Shuuji is simply discovering and trusting his own sense of what is right rather than claiming a broader moral high ground, which I believe is the case here. It’s probably why it’s written in quotes (『正しさ』), perhaps implying subjectivity since it comes internally from Shuuji’s own judgment.

Now, to connect my interpretation of what “正しさ” means with what I said earlier before about the line intriguing me: the line makes it seem like Shuuji’s sense of responsibility/duty (責任感) isn’t necessarily the same thing with what Shuuji believes to be right. The way Cherubimon puts it implies that duty is external, and this new thing that Shuuji discovers comes from within and it’s what has triggered the evolution. In other words, Shuuji finally finds it in himself to just follow what his heart believes without getting too concerned about what others think of it, instead of constantly focusing on fulfilling duties and obligations in response to external expectations, which is represented by his strong sense of responsibility.

The dialogue that comes after that line drives home the point even further too — Shuuji wonders if what Cherubimon calls his “rightness” is just his ego talking (the Japanese word used for this is literally also “ego”/“エゴ”). Instead of saying he’s wrong for thinking about it like that, Cherubimon reassures him that he doesn’t care whether his “rightness” is driven by his ego or his selfish desires (身勝手), because to him, it still holds value if it can be shared with and understood by others. Essentially, Cherubimon is saying that Shuuji’s own personal beliefs or actions are valid as long as they resonate with someone else, making them his form of justice or righteousness (as a note: “正義” usually translates to “justice” in English, but I think this is where the word “righteousness” would be appropriate to use). He wants Shuuji to realize that personal motivations can still lead to something meaningful and just when they connect with others. I personally find how this is incorporated in Cherubimon’s evolution beautiful — it’s in the way Shuuji finally allows himself to embrace his personal beliefs after struggling with trusting his own heart (since it’s been long overshadowed with his need to meet the expectations imposed on him), and by doing so, he doesn’t just empower himself, but also enables Lopmon to reach his final stage of evolution.

Note: Something else I noticed just now, even if not very relevant to this writeup, is that Cherubimon uses the pronoun boku/ボク in that particular line, which is inconsistent with the pronoun he usually uses (watashi/ワタシ). I wonder why that is, but I figure it’s simply just a slip-up.

25 notes

·

View notes