Riting is an experiment in writing that engages with performance happening now in Los Angeles. Riting is a ground for encounters between artists, their critical community, and the public they belong to. Riting brings together a multiplicity of bodies and a polyphony of voices. Riting supposes there is no definitive untangling. Riting assumes mutuality of investment in the ecology of performance activity in this city.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

This Emancipation Thing by Sara Lyons

Carolyn Mraz on This Emancipation Thing

A soft beginning, cookies, invitation to join the stage. Casual. Hanging fabrics, bedsheets, crochet, “women’s work.” Video, a question: favorite childhood toys? As training for your role as [woman]? Conversational

More ideas, led and spoken by performers: Abortion Sex Orgasms MEN--Love? Sex? Relationships? Domination Body. Gender. Motherhood.

Autonomy With choice, comes loss Intergenerational conversations There is freedom, but that means decisions

We see and hear past documents and records Spoken and stitched together, A collage, a quilt maybe Of past experience to now Fold in our new age of technology, the video, the audio recordings a mash together, overlaid the present voice repeated in history

There is a blend here, a way of documenting, I was here, I existed, we are here, we exist

The individuals remain clear, and yet, some themes repeat. In closing, the audience acknowledges and speaks the connections out loud:

With choice, comes loss Loss, which allows new things to grow Autonomy, with which comes very hard decisions An inter-generational appreciation of the roads behind and in front of us

There is so much here. Heartfelt moments of honesty from the performers, the audience, the history -– the room is rich in experience, sharing. There is more to appreciate here than possible in our short time together-- How to experience what we can, in the time we have.

This feels right in the moment, and it feels far away from the second-wave “woman-can-have-it-all” time-period that grounds the show. Choice by choice, I define a life, each decision precluding a different possible outcome. It is specific and it is MY OWN. Maybe we can have it all, as a collective -– if we see and value every individual

We are joined in a cocoon of theatrical exploration here: magical but temporary. Our time is 2023, yes some steps forward and also the dismantling of things earned fifty years ago. Did progress seem inevitable in 1973? I don’t know. It doesn’t seem inevitable now. Maybe the ‘70s setting here -– warmly patterned clothes and a momentum of broad activism –- is a reminder of a time more filled with hope, listening, and action.

Carolyn Mraz (she/they) is a set designer, educator, and theater-maker/collaborator based in LA and NYC.

This Emancipation Thing was presented at REDCAT on December 9, 2023. It was performed by Jennifer Jonassen, Jack MacCarthy, Staci Mize, Chenoa Rae, and Michelle Sui. Photos by Angel Origgi.

Sara Lyons is a Los Angeles-based director and theater maker creating new performance forms for queer and feminist futures.

0 notes

Text

Bad Stars True West by Amanda Horowitz

DJ Hills on Bad Stars True West

Two images have stuck, like pin art, in my memory.

The first is Jess Barbagallo as Cricket, knife in hand, toaster between his legs. Despite the chord, dangling, obviously unplugged, I still flinched when Jess dropped the knife into the toaster. A fear leftover from childhood. There was a time when I was sure a toaster would kill me.

The other image is of an open briefcase, wet pasta spilling out into a bathtub. Wild and so earned it felt inevitable, this moment comes after a verbal tennis match in which Arne Gjelten performs both mother and father, voice and body contorting to fit an idea of gender that is as slippery as it is ever-present.

Bad Stars True West is a game—like the ones I hope we all once played with friends—where a train track-rug bears very real possibilities for travel. This game-nature allows danger to lurk so innocently at the edges of the play.

We are all in danger. We are all having fun. Anything can happen. Every moment is a surprise.

Boundaries are fuzzy in Amanda’s world. Images and words bend around us, reshaping themselves, beat by beat, into familiar things made unfamiliar.

Outside the gallery, Hollywood, too, feels even less tethered to reality than before. I’m still in child’s play mode. Each person I pass on the street has a little cowboy inside them. There could be spaghetti in anyone’s briefcase.

DJ Hills is a writer for the page, stage, and screen. They are the author of Leaving Earth (Split Rock Press) and their play TRUNK BRIEF JOCK THONG was shortlisted for the Yale Drama Series.

Stacy Dawson Stearns on Bad Stars True West

Sam Shephard holds a wiggly warm spot in my dirt. In the 80’s, I was a young teen and already starting to feel out of place in the creative boxes available to me. The play Cowboy Mouth showed up. Shepard and his unique troping of the American West plus asphalt and addiction tripped my switch so I tried it on, acting out scenes and making costume designs for characters I didn’t understand. I was just a kid and had no idea what addiction and love do to each other, no idea about the thin line between obliteration and inspiration, no idea how hard it is to stay free when you cross the threshold from childhood to the big A. But I learned that Sam and Patti Smith were lovers who had written and acted that play out together, so maybe the line between fake and real was a dotted line. Is it a coincidence that Patti Smith made her public debut as a poet at St. Marks Church on the same day I was born? Funny that I would debut artistically there, too, 20 years later performing on the 2nd floor at the Ontological Hysterical Theater. Dotted lines on road maps worn thin from thumbing connect disconnected folk to one another. Ghosts of the living and dead love churches that act as theaters.

I moved to NYC 6 years after my first exposure to Shepard and saw a flyer wheatpasted to a mailbox for a production of Cowboy Mouth. The theater was a basement in the East Village. Ghosts love basements, too. The mythical Lobster Man character was played by a guy with no clothes on- very unlike the Lobster Man costume design I had drawn years before, but much more honest and economical. I couldn’t believe how weird and normal the play was and how easy and hard it all seemed at the same time and how it made sense without making sense. I figured that Shepard was my uncle and these folks were my cousins: children of an America made of narcotics, disfunction, TV, and asphalt. It felt good to sit without lies for a while.

30 +years later I’m in a small gallery space in Hollywood seeing a play by a playwright named Amanda Horowitz that spawned somehow from Shepard’s True West. Ghosts are ok with galleries. Sam wrote True West 9 years after Cowboy Mouth- but with Uncle Sam it’s all just one play, really. Different acts. I came because I wanted to see Jess Barbagallo, who is a rock star of an actor just like Malcovitch or Shepard himself but braver, more vulnerable, tougher, softer. Shepard no longer lives in flesh- he is a ghost grampa who passed out and left the car keys on the dresser next to his drumsticks. He is sitting with me on these metal bleachers a block away from the Boulevard of Broken Dreams, fading in and out of vision depending on the angle of my glasses. On the stage, wild ones with their hearts pushing through their shirts are taking his car on a joyride into new territory: a wormy place of what we do when fucked up romance and being sad about wasted people is no longer enough. They run off the road in a town called Almost Hope, population 3.

Bad Stars True West is a beautiful evolution of Shepard Country where surviving the death of relationships is worth trying. Where the threat of being run over by a train is no worse than the threat of not being run over by a train because worms survive and thrive. Where mother and father are an actor who has noodled himself into a Mobius strip: self-contained yet unwieldy, feral yet capable of being studied. Jess is not the only star in this trio; Arne Gjelten and Sophia Cleary end up rocking my world, too.

On the sidewalk after the show, Jess and I talk for a minute about the ways we all put out for our own art, and how great it is when projects feel necessary and fullfilling. Part of me feels like saying “feels like old times,” but I don’t want to. Nostalgia sits too close to atrophy for me, so I choose gratitude for this hijacking of Sam’s direction, saying in my mind: “Thank you for acknowledging that we are way beyond the era of hopelessness as a statement. Thank you for not being snarky and guarded. Thank you for discussing platonic love and heartbreak.” In his day, Shepard did not write to celebrate abuse and codependence per se, but at some point in the rotation his plays stopped being exposed wounds and started becoming reliquaries. I am not saying these plays have lost their prescience, I am saying we have a hard time being present*. Sometimes textual legacies need not be revivals. Enter Horowitz et al on the dusty horizon of Shepard Country. Having eaten the old plays like worms in a corpse, they split in two and regenerate their own heads. They fill a bathtub with spaghetti, they lay down on the tracks. Mom becomes an artist but maybe she always was and we didn’t notice. As still night falls on Almost Hope, USA, we don’t know where this is going, but we feel like we just might get there.

*Say a little prayer for Buried Child to erupt through the floor of the Supreme Court soon in a showdown of the undead! We can dream, can’t we?

Stacy Dawson Stearns (she/they) believes that artists support societal well-being by modeling and instigating collective creative practice. A Bessie Award-winning artist known for her work with Big Dance Theater, David Neumann, Hal Hartley, and Blacklips Performance Cult, Stacy has choreographed for pop icons Debbie Harry and Ann Magnuson, House of Jackie, and The Vampire Cowboys, and has performed and presented in 10 countries in venues ranging from NYC’s Lincoln Center to Tblisi’s Teatr Griboyedov. Stacy develops new media with Channel B4 and uses her curation and programming to serve communities and further social justice, representation, and accessibility initiatives as a CultureHub LA 2023 Fellow.

Bad Stars True West by Amanda Horowitz was presented at STARS Gallery in Los Angeles on July 13-16, 2023. It was performed by Jess Barbagallo, Sophia Cleary, Arne Gjelton, and Beaux Mendes as the "plein-air-painter." All photos by Jonathan Chacón.

Amanda Horowitz is an interdisciplinary artist working between performance and sculpture. She writes and directs theater projects with experimental and collaborative methods. Past performance projects include: The Plumbing Tree (co-written & directed with Bully Fae Collins, 2018-19), Suddenly, This Summer (2019) and Bad Water True West (2022). She is currently a 2022-2024 Playwright-in-Resident at Rutgers University.

0 notes

Text

BBC: “BigBlackOctoberSurprise” by Paul Outlaw in collaboration with Sara Lyons, Jonathan Snipes, and Adam J. Thompson

Badly Licked Bear on BigBlackOctoberSurprise

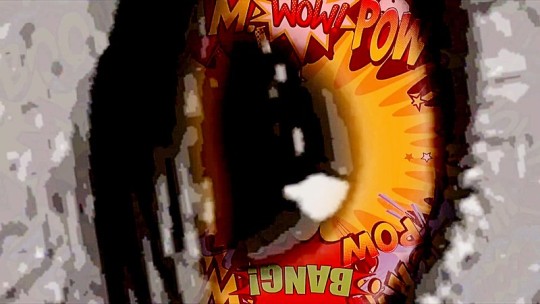

“The distance between us is not one of space, but of time.” You have always been here. You were born here. It is likely that you will die here. But you are only sometimes aware of that. Some are more aware - much more - of this truth. It might do you well to listen. The call is coming from inside the house….

BigBlackOctoberSurprise is a story told from a certain interior, the interior of the body. It is told from deep inside the gristly, scarred entrails of the American body politic. Imprisoned within a series of visceral chambers, Outlaw shuffles the deck of past, present, and future, ultimately demanding release not from one’s own body, but from the body politic wherein one was both born and is, ultimately, consumed.

The exterior of this body in which we discover ourselves, whose constant motion abrades us, dissolves us, and ejects that which remains, is beyond our direct experience. Our reality is deep inside, that, even as it grows harder and withers more by the day, the military march of its heart deafens us. It would be generous to name the condition here as twilight. If there is a light at either end of the tunnel, it is a light that will not shine upon our living flesh.

That there is a sweet-scented exterior - the space beyond and the time beyond that which is carceral and corporeal - is known to some, as it is not beyond the dreams and necessity of desire that blossoms in pain as it is passed from body to body for generations. That future demands not that one weather acidic, false-promises of release and salvation, but that our very life - all life - depends on being both indigestible and willing to cut passage to the light, blood-shiny and wet.

Badly Licked Bear was strongly considering wearing a mask for the remainder of their days, during all public life, before it was cool. An avid birdwatcher, they see Black Swans everywhere.

Lauri Scheyer on BigBlackOctoberSurprise

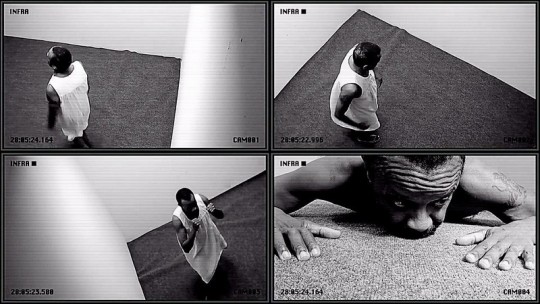

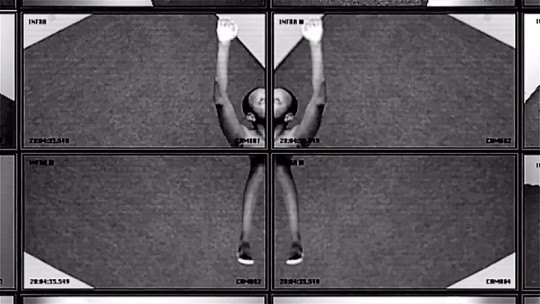

Cryptocurrency—a stand-in for a stand-in—came to mind as I bought “a ticket” from the restricted space of my computer. I wonder how it would have been different to watch the piece, this play about the black male body in restricted spaces and restricting guises, as it was first workshopped, in a theatre. But how better to watch a play about isolation and separation than from our own cells? I thought about witnessing the life squeezed from George Floyd on video—about the positions of onlookers in front of Cup Foods, the police, with their bodycams, or Darnella Frazier. “BBOS” is about the violence of these multiple perspectives; it's about seeing, being-told, and then re-told.

Outlaw tells a different tale of a black man's murder. This time the context is the dirty-secret consensual sex (one of the ironically framed ‘big surprises’ of the title) between an enslaved black man and white plantation owner. The men were observed (surprise!) by the plantation owner’s wife who then surreptitiously (surprise!) ordered the dismemberment and murder of the enslaved man. Being-seen and being-told. We ask what we see and from where, and how this position impacts what we feel and understand.

A white woman opens the play claiming, “I am Paul Outlaw,” but this is not a game show of “true identity,” or the territory of “I am Spartacus” or “We are the World.” Our sense that she is not Paul Outlaw is only intensified by her claim that she is. When we see Paul Outlaw at the end of the play, we have seen him in multiple guises—white woman, Kafkaesque vermin, potent black male body—and in multiple enclosures—a cell, slave quarters, pandemic-era virtual square. Throughout, the black male body is universalized as a perceived instrument of aggression, and at the same time it is almost infant-like in its helplessness and guilelessness—another trope turned on its head. Now, at last, we see the presumably autobiographical Paul Outlaw (or as close to him as we can get), and we understand the extent to which no one can inhabit Paul Outlaw but Paul Outlaw himself.

“You ain’t gonna bother me no more, no how,” Billie Holiday sings, at the beginning and end of the performance, but this remains wishful thinking. We have watched “Paul Outlaw” shape-shift, only to finally become “himself.” And yet we can’t un-forget the anonymizing and objectifying we've just witnessed.

A command rings in my memory : “Get out of here!” Is it a note-to-self, or a command from outside? My memory is of a body not standing vertically of its own power: the body is crouching, writhing on the ground, in a fetal position, seated in a chair. Big black cock to big black cockroach—their threat and vulnerability. The ambiguity and bivalence of both symbols.

“This is not intermission, by the way, and it’s definitely not the end.” I’m waiting for his next production.

Based in Changsha, Los Angeles, and Chicago, Lauri Scheyer is Xiaoxiang Distinguished Professor and British and American Poetry Center Director at Hunan Normal University. Her most recent books are Theatres of War: Contemporary Perspectives (Methuen Drama/Bloomsbury) and A History of African American Poetry (Cambridge University Press).

BBC: “BigBlackOctoberSurprise” was presented virtually at REDCAT October 22-31, 2020. Concept, performance, and script by Paul Outlaw. Directed by Sara Lyons, with sound by Jonathan Snipes and video by Adam J. Thompson.

Paul Outlaw is a Los Angeles based theater maker, lyricist and vocalist. For more about his psychedelically Black, relentlessly queer visions, please visit outlawplay.com.

0 notes

Text

It is Dense and Bears Repetition: Notes on Rehearsals of Asher Hartman’s The Dope Elf by Neha Choksi

i.

I might as well as confess: to witness some things over and over is a fascinating pleasure. I like seeing rehearsals not merely because they revel in repetition, but because they necessarily incorporate change overtly and experientially for everyone present—including me, the embedded witness.

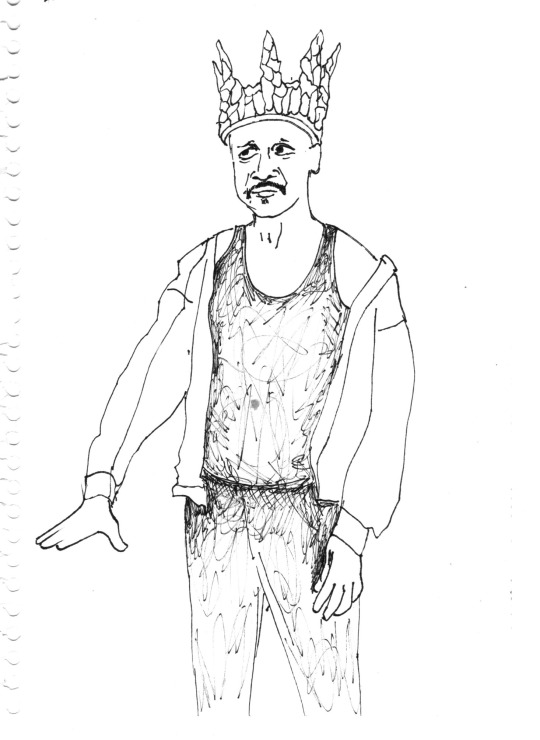

In April 2019, I started attending rehearsals for Asher Hartman’s The Dope Elf. The piece uses characters akin to northern European mythical creatures to explore the legacy of white supremacy in the United States. The first—and because of COVID the only—showing of this work took the form of three elaborately-plotted plays, with scenes following each other according to a sometimes inscrutable logic, unfolding over three consecutive days. (There are more plays to come in later showings.) The actors lived on-site, slipping between self and role, in a trailer-park-like installation in a cavernous space. This double use of the site—as actor accommodation and performance venue—points to the way in which Hartman sources each actor's multiple characters at least partly in each actor’s own shadow self and emotional make up. One might say that he is similarly mining America’s shadow self, beset as it is with the ills, aches, and pains that attend its settler-colonial DNA and live on in its trauma-bearing white supremacist structure.

Rehearsals had begun in early 2019, four months earlier, and I continued attending intermittently over the course of the next four months. I wanted to see how Asher’s thickly-worded, joyously-crafted works came to be within a community of actors. The actors were Zut Lorz, Philip Littell, Joe Seely, Paul Outlaw, Michael Bonnabel, and Jacqueline Wright as the Dope Elf. I was interested in Hartman's rehearsal process, but I was equally interested in what it might mean for me to revisit something again and again. I was then repeating kindergarten, attending school daily as a kindergartener for my own lived performance project, and I was interested in repetition as a productive space, generating surplus meaning and unfolding thoughts.

ii.

Rehearsal-as-work is itself a knotty concept: the repetition is simultaneously labor, process and product/ion. Think of Ragnar Kjartansson’s Bliss at REDCAT last year, in which a three-minute excerpt of the finale from the Marriage of Figaro—the part where the philandering Count successfully pleads forgiveness from the Countess—is sung by the cast repeatedly for twelve hours. That “Contessa Perdono” finale is well-known and thus it was not difficult to take the whole in. The nuances and differences in each serial repetition and its sheer duration made the piece work. But take a typical Asher Hartman play—erudite, wordy, noisy, and well-jointed—and I would have to say: the labor, process, and production are all dense and bear repetition.

I attended at least ten rehearsals, two fund-raising performances, and a tech meeting. The rehearsals had been in progress for several months by the time I joined, and took place either at Asher’s studio or at another location which had space for scenes with extensive movement. Some of the scenes that I saw rehearsed again and again were etched in my brain, but largely the onslaught of language and prowess of the actors overtook any attempt I might make to disentangle the narrative threads. The language was fiendishly intricate and the actors enrapturing. The most important takeaway for me was how the experiential onslaught of an Asher Hartman play doesn’t diminish upon repeats. It grows into something more powerful, the way poetry learned by heart does, at least for me. Because I purposefully never read the play script, and because I saw bits out of sequence, I remain to this day largely puzzled about the storylines, if one can even call them that; however, my sense of the texture of the characters and the power in each word they uttered increased with each repetition—even within a single rehearsal session. Here is a one section of Asher’s text that I heard over and over and faintly understood to be about a tussle between rival interests for control of a place called Bodysnatch Lane. Here the Princes of Undeath, who is also an American bore, is excavated nightly, in a recursive bit that alludes to American hauntings and mimics my own labor of repeated rehearsal viewings.

The more I saw this scene rehearsed, the more I knew it to function through the language, consciously playing with the listener’s bewilderment. And yet the resurrection mingled with the deadening injection conjured the haunting numbness around meaning that repetition can produce. When I first tried to write a draft for this report on the rehearsals, it came out something like this:

It is dense and bears repetition. It is tightly packed and could be repeated. It wants to be dense and enjoys reiteration. It was fitted like a Rubik’s cube and could be manipulated ad infinitum. It can be opaque and will bear repeated viewings. It was fluid and vast like an ocean and allowed for continuous indefinable waves to wash over me. It was impenetrable and welcomed the battering ram of persistence. It is self-referential and needs recurrence to be communal. It will be dense and will bear re-enactment.

It was my experience in a nutshell. Novelist Tom McCarthy points to something similar in reference to Winnie in Beckett’s Happy Days: though Winnie says she is going to perform the exact same action of removing her mirror from her handbag the next day, it is not actually possible for a repetition to be exact—the memory of the earlier action changes the perception of the later one. It is not a repetition so much as a re-enactment of an action that is first tested and then re-enacted; and then there is a re-enacting of the re-enactment. What happens to one’s experience of time when faced with these recurring enactments? It becomes potentially endless. You become committed to reviewing the material, regardless of whether the time embedded in the material itself is slight or vast. The act of revisiting the rehearsals and the actors' own repeated endeavors conjured the feeling that this could go on forever, this honing, this shaping, this readjusting.

iii.

Asher’s skill shone in building on the actors’ proclivities and input to craft each character's behavior and inner life. If the actor’s personal tastes and tendencies, known to Asher from prior collaborations and extensive unpacking while first working on this piece, were fundamental to writing the characters, they remained essential during rehearsals. Characters' unknown histories, unconscious drives, unrevealed passions and clarified micro-aggressions were all attended to, heightened, or left to simmer and bubble into the work. The crux of it, at least as I felt it presented in the words of the piece, was that all the characters—and thus we humans—are needy in some way or another. Those pushes and pulls of the actor’s and character’s needs were key in how I saw Asher tend to the work, the larger purpose of which is seemed to be a deep illumination of the needs and psychic pains inflicted by the demands of the white suprematist superstructure. As a director, he was always reassuring and relentlessly positive, sticking to the principle of “Yes, and…” (which the improv world recognizes as a way to build on each past action, constantly relaying the baton).

By the time I was in attendance, there was not much improvisation in rehearsal. However, the actors had a lot of leeway within the structure the language provided. Asher was open and supportive, and refrained from giving too many stage directions. He was compassionately engaged, listening, noticing; he attended to the slightest shifts in tone, mood, and body positions. Feedback did not happen at every rehearsal. It was only after multiple rehearsals that there might be a roundtable to go over his notes. The result was a seemingly non-hierarchically-motivated, mostly supportive, and non-critique-heavy space.

Still, each actor had a different relationship to Asher and his work. There were outbursts of: “The writing is so fucking good!” and “I am not a good enough actor...” There was a sense that: “It’s [the script] so spare, we don’t need an extra layer of Beckett.” And: “There is no theater space in LA for this... it is really Asher’s imagination!” This attitude asserted the primacy of the director, and Asher didn’t really try to mitigate that sense. It was his work in the end.

iv.

Rehearsal was work, no two ways about it. It was an act of refining what would be many scenes over multiple days for a public performance, with Asher trying to pin down the tenor of each section like a slippery wrestling opponent. Horseplay was limited to what could benefit the work. Rehearsals were calm and organized. Each day's agenda was decided roughly the week prior and revised as-needed.

Carl Weber once described his first visit to a Berliner Ensemble rehearsal for Brecht’s Urfaust in a way that made work and relaxation seem identical:

I walked into the rehearsal and it was obvious that they were taking a break. Brecht was sitting in a chair smoking a cigar, the director of the production, Egon Monk, and two or three assistants were sitting with him, some of the actors were on stage and some were standing around Brecht, joking, making funny movements and laughing about them. Then one actor went up on the stage and tried about 30 different ways of falling from a table. They talked a little about the Urfaust-scene 'In Auerbachs Keller' […]. Another actor tried the table, the results were compared, with a lot of laughing and a lot more of horse-play. This went on and on, and someone ate a sandwich, and I thought, my god this is a long break. So I sat naively and waited, and just before Monk said, 'Well, now we are finished, let’s go home,' I realized that this was rehearsal.

The loose method of the Berliner Ensemble was generative for Brecht, but at this point in the process, Asher’s rehearsals involved not so much trying thirty different ways of doing one thing, as much as honing the one thing that Asher's language had established. With each repetition, the company digs deeper into what is already there. Asher and the actors never treated the rehearsal as a break, nor the breaks as potential spaces for tackling rehearsal questions. The non-work-related breaks were short ones. At one rehearsal space, this meant fueling up on the much-favored licorice and other snacks. The second space forbade eating of any kind and the breaks were just solo and chitchat time. The only other “breaks” from being on the floor with the text were either discussion of matters pertaining to racial context, mythological sources, character background, or feedback notes. And, of course, warm ups.

Here are two of the warm-ups Asher led on “Movement Mondays”:

Imagine legs with magnets that go down to the start of time through layers of rock.

Imagine heads beaming into infinity.

Now let’s do some body rolls and exercises to move the body.

Now let's do energy readings of each other. Feel the energy field.

(Here I tell AH, “I don’t know if I get it.” Trying to reassure me, AH says, “Most people can’t visualize it.” I say, “I’d rather be touching.” “Imagine that as a bumper sticker,” is the joke reply. So, I imagine cars touching or crashing.)

And:

Pick someone to follow without letting them know you are following. Don’t indicate to them or to anyone else. If you are being followed, lose your follower.

Get connected, or get paranoid.

Don’t lose sight. Concentrate on a part of someone else’s body, follow it, then join it, that is, attach to that part somehow.

Unfold out of the conjoined position slowly.

Asher’s method was to let the actors show off, go big, and play, and then rein them in and slow them down. There were injunctions to remember gestures from last rehearsal. A few times, when Asher referred to a narrative thread or story development, the actors looked confused. Asher had to explain that he hasn’t written that part yet; he was considering it. Things were in flux in Asher’s head, for sure. Although individual lines were not undergoing much revision, entire sections were being added or dropped. Sometimes lines were cut because of something an actor did inadvertently that worked. Asher was open to that.

The discursive space around the work seemed vital to everyone. During a snack break, Joe said that having conversations with Asher felt like being a kid on grandpa’s knee. Philip talked about what it meant to have Asher channel Philip's own real-life drives into a character. “I wanted to scare people, to confront infirmity and death,” he said. ”And I am always up for an anguished argument with my sexual life.” Joe added, “I wanted to experience love, but Asher subverts [that desire]. He starts at A and ends at 17.” In working on the piece, he felt challenged to “own my own gravitas which I often negate.” Zut said that the work challenged her ability to take up space, on the one hand—”and then I become the void.”

v.

Here are some of Asher’s interjections to the actors culled from multiple days of rehearsal:

“Hold it, don’t speak.” “Let it go.” “Stop right there.” “If you feel like it.” “Find the gesture.” The Old Woman character says: “I am not there yet. You want me to find it.”

“Yes.” “Hold it.” “Release that.” “Just go really still, Joe, and use your voice.” “That’s good.” “That’s a great note.” “Decide whether you are going to inject him.”

“Really slow it down. Register gestures if you want; I won’t orchestrate it.” “Lets slow it down... 3…(trails off), just in short phrases.” “So slow it down, pause and allow him to reveal how he feels.” “Assign each person a color.” “Take the fluidity and naturalism out; replace it with slow tics and stares.” “Are you creating this scene or observing it? You can never be a part of it.” “Use angles, not arabesques. Open, not clumps.” “She has a full fridge and pays her internet bills, as background.” “These two might eat in the same restaurant together.” “Repetition is making you rush. But there is no need to rush. This script needs space, pauses, multiple speeds.”

vi.

The manner in which rehearsals are conducted says something about the director’s conception of society in which this theater is made. Asher made a generous space with room for intuitive reflections. Even my position as an observer became the subject of discussion. Nothing was recorded; everything was left to be reviewed in the director’s head and the actor’s somatic memory. Only the text was not improvised but pre-written and pre-memorized.

The rehearsal world always mirrors the larger world’s concerns, whether intentionally or not, and the language-trauma embedded in the text allowed the actors at times to ask larger questions that took a distinctly political turn. Asher explained that in conceiving this play he was thinking about white supremacy through Viking/Nordic/Teutonic lineages. The mythic past he conjures in the text leaks into the world as it is today, and into the plays-to-come. He urged actors to remember that, in the world of the Dope Elf, “There is no morality—there are no limits, no codes, not even like the Mafia, since the Mafia has a code. Here if you don’t kill, you will be killed.” At the same time, “The relation between gods and ordinary people is close.”

Conversation slipped back and forth between the world of the play and our world. “What the whites have done is pretty mind blowing. Think of Haiti,” Asher said. Racist behaviors and habits, he insisted, are embedded in our culture: “Everything keeps repeating again and again.”

Jaqueline responded that she wanted no part in that repetition.

Asher turns the conversation to violence. One way to deal with violence, he says, “is to move toward it.” Another way is to insist that you “won’t be cornered.”

In that situation, he said, “the dance changes, and it can work.”

vii.

Let me focus on one scene. It is about John and Alfred, a couple who have been together 30 to 35 years, but who now are unhoused and making do on the streets. The scene focuses on Alfred’s attachment to and concern for a bird that used to always visit him and has since gone missing; it touches on the resentments that this attachment draws out from John. The menace isn’t far from the love.

Asher. (to Michael, who plays Alfred) Is there anything [present in your exchange with John] in terms of your desire for him? Michael. This scene made me realize it is fluid. I do have feelings [for him] but this sex is just to get him off since I have no place [else] to go. Asher. Do you have any skills? Michael. No. The actor does. [The character, Alfred, is also an actor.] Asher. When did he [last] work? Michael. He does odd jobs. He used to be good at decorating and keeping house but has lost the patience for it. He was probably a florist. Asher. Is he cooking? Michael. He cooked more [before]. Asher. Making the house nice? Michael. Yes. Asher. Is he home most of the day? Michael. Yes. Asher. TV? Gardening? Michael. No and yes. Asher. What are you reading primarily? Michael. Biographies, so he has knowledge and taste, but he has lost interest [in the world]. He is just surviving. Asher. Who is this Bird? Michael. My baby. I watch it every day. Always the same place, same branch every day. Bird brings me joy, but I envy its happiness, its energy, its flight. Bird represents something out there.

Asher. (to Philip, who plays John) You have headphones and exploit opportunities to use them so that you don’t have to listen to him. Who controls the relationship?

Philip. [There are] Two controls. I was the sparkly star but I lost my nerve. I control my helplessness. Helplessness [was] a catalyst for [our] eventual homelessness. I am in charge of keeping it light. (Pause) I lost my nerve 10 years ago. Asher. What happened? Phillip. I lost my work. Asher. What [work] do you do? How [did you lose it]? Helping? Philip. [I was] helping people with parties, going through stuff, discarding estate sales, [addressing] people’s needs, [like a] flea market assistant. (Pause.) I am good value. I haven’t made good friends and the sexcapade market has declined. But at home I am the upper hand guy.

Asher. (to Michael) Do you fear him? Michael. I used to but not now. Asher. Do you have any contempt? Michael. A great deal, for losing himself. He is caught in the undertow and cannot get to shore.

Asher. (new subject) What is the time of day? Michael. Evening, early evening. Asher. What time does the Bird come? Michael. In the morning, and then [it] comes and goes all day. It’s not come today or [for] a few days. It’s scary. Philip. I remember 10 years ago he had a bird in the apartment. Not sure. We are living in the same neighborhood [as when we had a home, even though now we are homeless and on the streets]. Trying to be vigilant. One of us has to be vigilant otherwise we will lose all our stuff. We’ve probably moved a few times to get away from someone, like “O, he pitched a tent here.”

Asher. Let’s try the scene again but close to each other, as close and wrapped up [and intertwined] in each other. I am asking [because I want] to get [at] this enmeshed, growing on the nerves feeling. When he says, “he’s my baby” about the Bird, how do you feel? Philip. I am your baby, asshole. Asher. If there is a discomfort in the body, use it. [How] agitated are you, Philip? Philip. Yes, I am not listening, I am not. Asher. Do you love the bird more than you love this man? Michael. Love the bird more than John? No, but it represents something.

The repetition with a difference succeeds in getting John to feel more disconnected and uncaring within the embrace. Is that Asher’s purpose? I can only guess.

In the third run through, as a result of the intertwining of the two actors' bodies, Michael/Alfred’s intensity increases, as does his touching, tapping, nudging, pushing, and shoving of Philip/John. Halfway through, they find themselves contorted and seated back to back, but Alfred keeps turning around to look at and engage John. Alfred’s words explode, his face hyper-emotional. Up and down, staccato to smooth.

This next section follows the bird discussion, and is about finding stray toothbrushes and unwanted used cans among the sleeping arrangements.

Asher. Do you enjoy it? When you find it [the toothbrush], does it feel like a victory? Philip. [What it feels like is:] I've got you now! It is a horror, but I've got you now! (Pause.) This loss of love section is clinical. We have common cause, [are] traveling companions, etc. We agree the world is horrible, monstrous. Asher. Are you trying to make this relationship work? Michael. Yes, it is difficult and he [my character] wants to kill him [John], but [John also] wants to be the one to end it. I am trying to make it work and he is not trying. Asher. Redo the section about the loss of love you’ve incurred in this relationship. [And the part about how] you want a refund).

Again, another run-through. And after:

Asher. John is very honest, almost cruel, you know? How he feels, how he reacts. Michael. It’s their comfort, in a way, to be that honest. Philip. We still play games with each other. Pretending to know the Bird, and pretending not to listen, but to be listening, etc. Phillip can get anyone he wants, but John is a failed version of me. Vanity is very me.

What was clear through Asher’s probing questions was that he was not directing the motivations or providing them in toto. Rather his trust in the actors and in the fact that not everyone knew what was in each other’s minds was relied and built upon. Each repetition pushed the work of the rehearsal forward.

The questions and answers generated more awareness while also inviting a realization of how little we know about each other—and indeed of ourselves. This yearning to connect and engage, the characters' missing each other and finding each other, and that craving embedded in John and Alfred's language moved me deeply each time in rehearsals. This, maybe, is where an important facet of white supremacy enters the work. To see the other people in one's life as irritants, to resent the sense of being stuck with them—this is how the structural force of racism wears us down.

viii.

I could feel the pressure mount as pencils-down time approached. The drive to access some authentic perfection and virtuosity remained. Rehearsal periods end. So how do we distinguish between a rehearsal and a performance, aside from all the tech and scenery? Theater can succeed and fail any time. You may prepare and prepare but you are always starting over. Renegotiating the unspoken bedrock of slavery and settler colonialism that is the terrain of our American society might require some of that tenaciousness and faith. Rehearsal can be a labor of pointing towards and then dismantling something – whether white supremacy, slavery, or settler colonialism; whether on the scale of history or the scale of an individual life. I never learned how this section with Alfred and John, dislocated from the rehearsal room to a performance space in Portland, worked as a repeated mise-en-scène. It does not matter. What I experienced the first time I heard it changes in retrospect, with each new repetition, and enlarges the connections I make with the real world pressures outside. The work remains suspended in the doing, and in our awareness of its re-enactment.

The Dope Elf is intended as a sequence of six plays. The first three plays was presented at Yale Union as part of the Portland Time Based Art Festival. The performance environment was open to the public September 14-22, with performances September 14 & 15. The fourth play in the cycle is currently being filmed to be viewable online through The Lab in San Franscisco in 2021.

Asher Hartman is a multidisciplinary artist and writer based in Los Angeles. His work explores personal and emotional histories in relation to ideologies that structure Western culture.

Neha Choksi is an artist who lives and works in Los Angeles and Bombay.

All drawings by Neha Choksi. Photographs by Ian Byers-Gamber.

0 notes

Text

On the Other Side by Marike Splint

Sara Lyons on On The Other Side

The beginning is deceptively gentle: four people appear on stage and stare straight at us. Chatter dissolves, eyes turn forward, and they hold our collective gaze, unflinching, calm, and direct. Audiences never know what to expect at the start of a performance; in this moment, it actually seems like the performers don’t either. One speaks after a long silence: “I don’t want to start.”

These words simultaneously spark and protest the beginning of the show — a dialectic that informs each element of this company’s unraveling of borders. Each performer has lived a life defined by borders between nationalities, citizenships, languages, and gender — now they occupy a space populated only by a few microphones on stands. They slip between documentary and abstraction, intertwining first-person storytelling, re-performance, and movement sequences to inspect “bordered moments” throughout their lives. Theatricality flips to disarming mundanity like a light switch.

The performers tell us that what we are seeing is not the show: it’s what was cut from the show. They wheel invisible panels across the stage with full allegiance to their existence, destabilizing our sense of what is and is not. Avalos describes crossing the Brownsville-Matamoros ‘borderplex’ from one home to another; Assadourian rants about impossible stereotypes she must navigate as an Iranian actress in America; and Outlaw recalls life as a queer, black American in West Berlin before and after the fall of the wall. “We are territorial beings,” says a program note.

Splint is a site-specific director who has worked in public spaces. Now, in a theater, she lays bare the social, economic, and political systems that create and interpret a work alongside artist and audience. America becomes her site, as it lives in our every breath, move, purchase, and turn at the ballot box. She reminds us that empires begin with a simple utterance: who is, and who is not.

Sara Lyons is a Los Angeles-based director, theatre-maker, and teacher focusing on adaptation, social practice, and feminist forms.

Elizabeth Schiffler on On The Other Side

the show began by defining

the space between people

Looking back at the experience, with the space between me-now

and me-experiencing-the-show growing bigger,

all of those borders and spaces have become stranger… I am new to los angeles theater, new to the city, and privileged in my ease of navigating borders as an american citizen. This was an opportunity to listen and watch those borders that are sticky and violent and unjust and bound, and three-five people who moved through the borders. I learned stories of border crossings and not-crossings, space and not-space, lines and not-lines.

Yes, I just listed a stream of paradoxes. We seem to live in that world, full of paradoxes, and Marike made messy those borders and lines at each level of this piece, down to the crossings of actor to audience, director to stage, and words crossing each other as the stories told were both clearly autobiographical and clearly not.

The microphone was a tool for Splint’s (not)borders. As an actor might approach the microphone to share something intimate from their life, such as their ability to speak multiple languages and the ways borders have left them out or on the fringe in America. They might later come to the microphone and speak for another actor, or with another actor, crossing bodies and spaces and the connections between actors were forged through the voice jumping stories, bodies, and space - as the show continued, these instances of crossings multiplied, making messy borders vivid.

On staging (not)borders:

looking forward, the borders of theater spaces will continue to change. cancellations of spaces abound due to COVID-19, (broadway was closed just today), and yet somehow we still can think and feel the performed story space - I think. Theater will have to be imagined differently, but as Marike has shown, it already has been.

Elizabeth Schiffler is pursuing a PhD in Performance Studies at UCLA and practices as a filmmaker and video artist, sifting through the multiple cultural, ecological, and transnational scales at which food and performance interact. She was the inaugural Artist-in-Residence at Seattle's Pacific Science Center.

A work-in-progress presentation of On the Other Side happened at the Skirball Cultural Center on February 21, 2020. A subsequent life is planned, dates TBD.

Marike Splint is a Dutch French-Tunisian theater maker based in Los Angeles, specializing in creating work in public space that explores the relationship between people, places and identity. She serves as a faculty member in the Department of Theater at UCLA.

Photo credit: Gema Galiana / La Mujer Tranvia

0 notes

Text

Hanging with Clarence by Rodney McMillian

John Story on Hanging with Clarence

In fall of 2019, artist Rodney McMillian presented Hanging with Clarence, a performance based on Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’ 1986 commencement address at Savannah State University.

The piece was staged at the Bethlehem Baptist Church, designed by the late Rudolf Schindler. A 2013 Los Angeles Times article described the church as “the lone example of Modernist architecture to cross Los Angeles economic and racial boundaries in the era of Jim Crow housing covenants.” The structure was built in 1944.

McMillian, adorned in a Catholic priest’s garb and snakeskin boots, approached the stage with two female performers. They made a slow march toward the church pulpit, while McMillian chanted ominously and the supporting vocalists harmonized. The phrase “dogs holler” pulsated in each line of his lament.

The artist took to the podium and a switch of character occured. He became the proud icon of black conservatism, Supreme Court Justice Thomas (though in 1986 he was Chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission).

Throughout the speech, the tone of McMillian’s Thomas was self-congratulatory. An awareness of personal triumph was identifiable.

Then there was a turning, a burst of sensuality. Red lighting emanated from the walls and ceiling. McMillian dropped and gyrated to a tune about an “unholy fountain” (reminiscent of the late Prince Rogers Nelson).

Several such bipolar oscillations occurred. The dignified regal Justice Jekyll switched back and forth with Mr. Hyde. In one interlude, Mr. Hyde exclaimed “terrorize yourself!”

In Thomas’ closing, he praised the previous generation, particularly his own mother. The qualities he uplifted in them were pious, humble and Christian; a silent endurance of suffering. An attempt to raise a future generation above the limitations of their own.

In the end, the audience is left with the age-old Apollonian/Dionysian dichotomy. Thomas, a black man in the highest branch of the judiciary, preceded only by Thurgood Marshall. Respected worldwide, the hope of so many, yet also Anita Hill’s terrorizer. What shifts occur in his psyche? The judge is known for his reticence on the court, compared to his colleagues. Perhaps McMillian is imagining what stirs under such stoicism.

John Story is a filmmaker and writer from Orlando, Florida, who now resides in Los Angeles. He is currently developing a coming-of-age screenplay about his hometown.

Philipp Farra on Hanging with Clarence

Two to three parts, a modernist church built in 1944 by Rudolf Schindler on the corner of Compton Avenue and 49th Street in Los Angeles, a commencement address speech from 1985 by Clarence Thomas, historical material placed in situ by a seemingly religious performance: a wooden crucifix behind the performing Rodney McMillian. The performance-concert: lighting, photographers running around, a public that sits in church benches while witnessing the spectacular event happening in front of them. McMillian recites parts of the commencement speech by Clarence Thomas at Savannah State College on June 9th, 1985, interrupted by performances—with Shauna L. Howard and Tekeytha Fullwood—of funk-rock songs written by McMillian and Tamara Silvera (“Living in the Buckle (for Mary)”, “Kill Me”, “Gas and Tabasco” (2012-2016)), George Clinton and Fuzzy Haskins (“Miss Lucifer’s Love”, 1972).

What is the history of that church, the connection of church and speech, and gospel, and modernist architecture, that lends itself to the re-enacting, re-performing, re-appropriating of Clarence Thomas’s speech? A pageant that embodies contradictions. In a contemporary performance landscape that often essentializes race and identity this performance is a reminder that race does not—

The performance complicates the notion of an easy understanding and reading of history, race, and, thus, identity. The discourse of identity politics presents race as a fixed entity, but how is it that a category that identity politics takes to be a fixed essence turns out to be so indeterminate?[1] Obviousness might be one feature of ideology: there was no obviousness in Hanging with Clarence. McMillian—who kept changing characters during the performance— between the speech of a former civil rights movement activist who is today a conservative Associate Supreme Court Justice and, between songs like “Miss Lucifer’s Love” and others of his own composition, McMillian as a writer, speaker, performer, singer.

It is complicated, history is complicated, History is complicated, a good complication. History has to be remembered, analyzed and reworked to inform the current discourse and future discourses, it seems that is, what McMillian communicates.

[1] Asad Haider, Mistaken Identity, Race and Class in the Age of Trump (2018): 43

Philipp Farra (b 1991, Schoenebeck (Elbe) Germany) is an artist currently based in New York City where he attends the Whitney Independent Study Program. He is interested in narrative structures and questions of representation through a Marxist lens within the context of art.

Hanging with Clarence by Rodney McMillian was presented at Rudolph Schindler’s Bethlehem Baptist Church in Compton on November 23rd 2019 by The Underground Museum, as part of the show ‘Brown: videos from The Black Show’, curated by Megan Steinman. It was performed by Rodney McMillian with Tekeytha Fullwood and Shauna L. Howard. The songs were written by R.M. and Tamara Silvera and produced by R.M. and John Whynot. The performance was co-produced by Rodney McMillian and Scott Benzel.

Special Thanks to Optima Funeral Home, Tunic Sound and Cauleen Smith.

Rodney McMillian lives and works in Los Angeles. McMillian explores the complex and fraught connections between history and contemporary culture, not only as they are expressed in American politics, but also as they are manifest in American modernist art traditions.

Photos by Christel Robleto, courtesy of the artist and The Underground Museum.

↩

0 notes

Text

SOMETHINNNGISALWAYSSSSWRONGGGG by Barnett Cohen

Hannah Spears on SOMETHINNNGISALWAYSSSSWRONGGGG

A woman stands in the center of a rapt audience, emitting a single, high-pitched note that erupts into a shriek. Another note crescendos and fades. Then a gasp. She’s just finished describing her mundane nightly ritual and “the voice”—a familiar voice, one with a personalized ringtone—that had interrupted it. Signaling an abrupt, unnamed calamity, this shriek is also perhaps what best encapsulates the overall sentiment of Cohen’s latest performance piece.

Written entirely in verse, Cohen’s script peaks and plummets, its darkest moments met with absurd humor. Tirades culminating in outbursts precede restrained, matter-of-fact statements. As if scrolling through a news feed, topics like environmental degradation and police brutality filter in and out. One performer wonders, passively, “Where do all the plastic bins painted with peanut butter end up? Is that smog in the distance coating my lungs from afar?”

Cohen dramatizes the latent horror of the national news cycle. Three of the five performers wear jumpsuits in different shades of red—not exactly prison uniforms, but close enough. The remaining two are in white hoodies that, combined with their pallor, intense stares, and Lynchian vocal distortions, suggest straight jackets. The lighting—a sickly, yellow-green—turns the whole space into an asylum.

This is the American dream turned nightmare—the sinister underbelly of what was once superficially bright, like the shiny, all-white baby grand piano that serves as the production’s only prop. Like the parts of its score that are pleasant and melodic before dropping off a cliff. Cohen’s piece portrays with palpable fatalism the gradual unraveling of what one performer can only describe as “whatever the fuck this is.”

Hannah Spears is a curator based in Los Angeles.

Asha Bukojemsky on SOMETHINNNGISALWAYSSSSWRONGGGG

“A story should have a beginning, a middle, and an end, but not necessarily in that order.”

Jean-Luc Godard

When I first experienced Barnett Cohen’s SOMETHINNNGISALWAYSSSSWRONGGGG during an intimate dress rehearsal, I was reminded of Godard’s quotation and the Dennis Hopper film that captured its sentiment. In The Last Movie (Hopper, 1971), the film’s narrative order is intentionally scrambled so one has to piece it together. In doing so, the film becomes a commentary on Hollywood, American influence, capitalism, and nostalgia. Like that film, SOMETHINNNGISALWAYSSSSWRONGGGG had me working to make sense of the characters and plot.

When I saw the piece in its final form I realized my desire to make sense was preventing me from experiencing SOMETHINNNGISALWAYSSSSWRONGGGG for what it really was: a performance. The actors were so talented and intensely engaged that I could let go of making sense and just take it in; fragments about love, fear, and the things we know but cannot name. Elusive and funny, the language was nostalgic, with old-fashioned words sprinkled amongst contemporary sentiments. SMS and Shakespeare. One performer exclaimed, “who goes there?!”, while another described a “beachy vacay” attended by handsome waiters—in a language not their own—before anxiously describing that something was “afoot”. Echoing formal theatrical roots, the piece was firmly planted in contemporary malaise.

There were moments when I wondered if the performers were still acting, or if I was meant to participate. Greek tragedy mixed with Beckett and Bausch. One of my favorite parts—a highly stylized, new age Greek Chorus—mirrored the incessant chatter of our own brains. The piece felt honest in not trying to make sense of our disordered, fluctuating lives: allowing anxieties of disconnectedness, earthquakes, guns, the fear of missing out and not doing enough, facing colonial pasts, race privilege and flawed history, dying alone.

Reveling in its own existential crisis, SOMETHINNNGISALWAYSSSSWRONGGGG was as much about living in today’s fucked up world as about the attempt to produce art within it. Like The Last Movie, the anxious state that produced it became its final form. The stylized presentation—saturated yellow lighting, red jumpsuits, white grids on the floors—all felt symbolic until it became apparent that it was only my wanting to make it so. Being lost, anxious and out of order was what the work was about.

Asha Bukojemsky is a Canadian / American independent curator and writer based in Los Angeles.

SOMETHINNNGISALWAYSSSSWRONGGGG happened at JOAN on November 22 & 23, 2019. It was created by Barnett Cohen in collaboration with performers Deja Bowen, Elisa Noemi, Danielle Swords, Bree Wernicke, and Roksana Zeinapur. The score was composed and performed by Daniel Bruinooge. Styling by Jenni Lee. Make up by Hayley Farrington. Technical Direction by McKenna Warde.

Barnett Cohen is an artist based in Los Angeles. He makes performances and paintings.

Photos courtesy of Barnett Cohen.

0 notes

Text

See You at the Funeral! by Tova Katz

Puppett on See You at the Funeral!

After Act I, my neighbor in the audience said something like “I don't know her. Is that how she actually is?” The performer had disappeared and all that stood before us was her character. “No. That's not how she is.” Our experience lived somewhere between the birth of this production and a baby in the woods. I was immediately the fan I was called on to be for this gay country singer. The audience brimmed with laughter -- engaged, at the ready. So when grief, infanticide, and PTSD infected the stage, the audience was absorbed and invested. We were surprised and anxious. Still engaged. And then she was gone and someone else emerged.

The set seemed to come from another time, but then it was seamlessly included and incorporated in Act II. Medusa strolled onto the stage and dominated it, commandeering both space and time -- our time. We revisited Greek mythology with feminist perspectives, revised our assumptions, questioned our judgements of good and bad. At the same time, we sat in the present, hoping for the worst, and knowing it. Getting excited when it came. Do we look away?

The set had become part of the story, only to be torn away and turned into something else. Act III began with rolling waves, oozing across the stage. It was the Broadwater, but no longer just the Broadwater. Now we sat outside place as well as time. Were we dead, or merely contemplating on the future prospects of our demise? A constant evolution. Evaluations, questions, humor, and introspection. An invitation to think about what we deserve. A chance to transform. Maybe we changed how we judge others and how we judge ourselves. And now we can reach for what we want without questioning our worth.

She walked slowly offstage. The cane clicking, banging, ringing. Echoing and fading into an introspective silence.

Puppett is a filmmaker and actor with a background in editing and post-production. Their films have premiered at Slamdance Film Festival, Inside Out, and Outfest, and in 2019 they played Max in the LA premiere of Taylor Mac's HIR at the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble.

Jason Lipeles on See You at the Funeral!

I'm looking over my notes scribbled in my journal. I circled "red lips" twice and "eyes" three times. I circled "question" and underlined "trembling." It was dark, I was scribbling, and I kept coming back to the actor's eyes— glittering and focused. I kept having this feeling like this black glitter would pour out of the actor's mouth. I imagined the glitter taking up her entire face and then swallowing the stage. Holding her fist over her heart she beat her chest and asked us to do the same. Creating music from nothing.

Her boots looked tan in the light but I learned from my friend that they were a dusty rose. I circled "control" and "stone" or is it "stare"? "ANGER" in all caps and "DO WHAT YOU LIKE" next to it. My notes don't capture it exactly, but they get close to the feeling of being between states.

Jason Lipeles is a Los Angeles-based poet, artist, and human-being-with-feelings. He is an alum of the AJU/Asylum Arts’ Reciprocity Artist Retreat. He graduated with a Master of Fine Arts in Image + Text from Ithaca College in 2018.

See You at the Funeral! happened at The Broadwater on November 29-30, 2019.

Tova Katz (writer/composer/performer) is an LA-based queer interdisciplinary theatre artist, creating visceral and socially engaged work that explores the intersections of relational, cultural, and mystical forces. Imagination saves her life every day. @tovakatzartist

Photos by John Klopping.

0 notes

Text

Kestrel Leah: Together (there) and Happy (here)

Kestrel Leah interviewed two different makers in two very different locations. Both identify as female, both are mothers, and both use autobiography in their work but with distinctly different approaches. She attended Lia Haraki’s rehearsal of her latest work, “Mazi (Together)” in Limassol, Cyprus in August, and sat in on actress Cristina Fernandez's rehearsal of her first solo show, “I'm just happy to be here”, which was presented as a Work-in- Process at LAPP's Word of Mouth, in Los Angeles in September.

Missive From Cyprus: Kestrel Leah encounters Lia Haraki

I tell Lia I’m not sure what time we’ll make it to rehearsal. I don’t drive in Cyprus—I’ve never driven on the left side of the road and I don’t have an international license. Here, I’m completely dependent on my partner to drive me everywhere, and with our sixteen-month-old in tow, this means my commitments revolve around naptime. Lia, a single mother of two, tells me to bring everyone to rehearsal. We enter the studio (late) to a room full of grins with a wide-eyed toddler in their midst. My partner shuffles our daughter to a corner, where she sits quietly mesmerized throughout rehearsal, mouth gaped open, at times tightly squeezing her papa’s hand.

Lia and her dancers are playing a beautiful game, it seems. Lia uses a made-up language of onomatopoeia to give direction, driving them with sounds like DJAH! DJAAAH! WA-WA-WAAAH! “I find numbers limiting,” she says, “One, two—what is that word?—because I think the sounds of some made up words have the energy of what you want.” Her collaborator Arianna Marcoulides comments that Lia has a special connection with voice, and rhythm, and how the voice vibrates the organs. This doesn’t give the whole picture. In 3 For Random, for example, Lia and Arianna improvise a non-stop vocal choreography of word-play, transforming text through relentless repetition while following verbal tempo-rhythms and psychological associations with their bodies as accomplices. Lia’s most recent work, Body Unmuted, is a sound installation where she only appears at the end.

The dancer’s faces are willing, open to receiving her, and without stress, as they feel their way through clunky hand movements, oozing ensemble gestures and primal murmurs. She is among them, animated by the rhapsody of inter-body collaboration, coaxing them towards unfamiliar depths of body and mind, but with a light hand. She’s giving direction as if she cares more that each individual feels what she’s getting at, rather than whether she gets to see it from the outside. One thing she’s sure of these days, she tells me, is that she’s a sharer. The title of the piece is Mazi (Together).

Meanwhile, it’s 40°C in Limassol and Lorca’s thirsty. As she grabs at my boob to feed, Lia’s face lights up. All she wants to do after rehearsal, she says, is put her boobies in the sea. Lia was recently diagnosed with stage one breast cancer, and had the operation to remove part of her breast. She wasn’t a good patient, she told me—she had a performance the week after her operation. Nevertheless, she’s taking it all as a lesson, she says—something she refers to as the transformation. “Big alarm. Big. I was in a space where I was not totally loving myself, and it was like, c’mon—it’s now or never. I was crying but … saying goodbye, to previous trauma, to previous selves, and at the end of these goodbyes … I knew there was so much happiness of what is to come.”

It’s no accident that this is what Mazi is about. Lia is transparent that each of her works is a reflection of what’s happening to her at the time. “This is the healing process,“ she says. “I can’t divide, I’m a very open person—whatever is happening in my life, that’s what it’s about.” Even though, to hear her talk about process, this isn’t a conscious decision: “What’s useful to me about the past few years is that we create intuitively, with the trust that later we’ll be able to understand what it’s about, so for me lately it’s a reverse process to what I was used to. It’s not a mental process. It’s a calling … It’s as if the piece is in another realm and we’re downloading it.”

As unearthly as this sounds, Lia’s work never feels out of reach. I first met her during last summer’s Athens Festival when I visited her pop-up The Performance Shop for a participatory one-on-one encounter called SKIN. Blindfolded, I was danced, spun, and seamlessly led by an undefinable number of limbs and mouths (a duo, only, it turned out) through a tour of my senses, using merely everyday stimuli like water, breath, pop music. Three months into the heightened psycho-physical state that caring for a newborn dictates, the total body surrender SKIN offered was exactly what I craved, as if the whole thing was just for me. It wouldn’t surprise me if this was a common response to Lia’s work. It seems that whatever the unique nature of each piece, through the candid personal narrative, through the profound playfulness, there is always an invitation to feel, and set free, something we don’t normally permit ourselves to—relief, pain, a dirty joke.

LIA: Why are people so emotional?

ARIANNA: I dunno … we gave them the space. It’s not something they’re offered, or that they ask for.

LIA: In rehearsal.

ARIANNA: I think maybe generally, in their life.

Kestrel Leah in conversation

with Cristina Fernandez

I made a thing.

I hope you like it.

I hope I like it.

I focus on the taped-off vinyl floor occupying a corner of the warehouse, and the few things it contains: an empty mic stand, the microphone casually snaking across the floor, a swath of purple fabric draped over a generic plastic chair. The magic potentiality contained within a dormant stage composition is one of the things that make theater, and waiting for theater to happen, feel like a ritual undertaking. Even in rehearsal. Or especially in rehearsal. Did I mention, there are unlit candles, and an invitation to light one.

(At this moment I cluelessly stumble over Jennie’s glass flask of water, turning it into a treacherous mess under our bare feet. Several-months-pregnant Jennie, graciously, marvels at how it was supposed to be shatter-proof, and we all agree we’ve gotten far clumsier since giving birth.)

Cristina too, begins as a threat of action. In a racy dance leotard and tights getup, she displays upon a small crate, every so often melting from one Olympian-like posture to another. Eventually, she slithers off her makeshift podium and hesitantly fingers the microphone. Once her lips receive it, it’s a soft “Hi.” “Hello.” Then a nasal “Hiyeeeeeeeee . . .” as if greeting the audience is to be rehearsed in perpetuity. Words shuffle and morph until Spanish starts to flow out of her, and she breaks into another, distinctly maternal voice. Again more repetition, again more neurosis: “I made a thing. I hope you like it. I hope I like it.”

This may or may not be a piece about making, but the struggle to make is present—maybe also the struggle to be—and with it a potential catharsis for maker and audience.

CRISTINA: I was excited, honestly, to tackle the solo—all of the tropes, and all of the magical things that can come from it. Literally conquering the solo. It’s just you on stage—but are you really alone? It’s so collaborative, you almost cannot do it alone. If you’re asking someone to do anything, to operate anything …

I think when I’m doing stand-up I’m trying to get at something more like this. It doesn’t have to be like “punchline, punchline, punchline,” there’s something really exciting about creating something new. I keep thinking so much about what you said, which is “You’re just gonna have to get in a room”. You were like, “Maybe the way you’re going to work hasn’t been invented yet”, and that was really true, there’s something about attempting that. Remember that?

The word-play and improvisation take more form and more force once Cristina lands at the microphone stand. I see the stand-up artist revealed, but she’s shape-shifting, toying with expectations and identity. Chatty quips roll out in an improvised auto-fiction that hints at geopolitics through a very personal lens. Sometimes tentative, sometimes gritty, here she finds her feet—literally and figuratively—and her voice.

WHAT IS GOING ON???

I read an article in the New York Times …

Do NOT go to the rainforest!

I AM GOING TO THE RAINFOREST!!!!!!

I’ll just strap my babies on my back!

It’s all about the gear!

CRISTINA: Yeh, there are these set markers, but there’s a lot of improvisation. It’s scary and super vulnerable … but there’s like a deepness to it, because it’s really all of the ways you are with other people all the things you’re performing, in your life. You’re bringing all this stuff from the subconscious and even you don’t realize how much of you it’s revealing until you see how someone is receiving it. You’re like, oh, other people are thinking about these things, we’re all just kind of coping …

I went back to my writing from when the hurricane had hit—I had forgotten about that—my mom was the face of something that was on the news … I’m thinking about Puerto Rico … I’m thinking about everything that’s happening … legacy and patterns and loops … and of course being a mom is in there. But in a larger sense, where am I coming from? And what am I leaving behind? That connection to Puerto Rico is getting really loud because I feel far away. I think there is this need to pass on to my kids some of that beauty and some of those traditions but also let go of some other ones.

When Cristina leaves the microphone, it’s as though she has exorcised fragments of a conversation in her head that is very much unfinished, and still waiting for its audience. In silence, she slips into a pair of sneakers, and perfunctorily begins to make rounds of merengue-salsa combinations that squeak and squeal across the vinyl. Gradually her hip-swiveling becomes more assertive, more concentrated, and with each loop of the dance floor she grows in intensity. The steps become exaggerated—not exactly expressive—but demanding. She tires herself, looking like this is something to get through, and dances right off the dance floor, making her exit.

CRISTINA: Work-in-progress is a tricky one because there’s an element of feeling not ready but allowing people to come in. The work is a practice—even if you’re opening the doors, how do you treat it as a continuation of that? There’s definitely the hangover afterwards where you’re like, “Performing is insane”. You reveal a part of yourself … and then there’s this wave of “What IS this?” But I’m excited to keep delving in. You’re touching on something, and then the audience is touching it, and you know it has some power.

I feel young in making my work, I’m really just a toddler. And, who cares? Who cares? I mean really, “Who cares?” is a good one. The time is now. It’s fleeting, it’s going to go away. It feels so important—and it is important—and it’s not important. You’re going to take yourself seriously, but not too seriously.

photos by Kestrel Leah

Kestrel Leah is a Los Angeles-based performer and director who loves documenting other artists' work.

0 notes

Text

Hi, Solo # 9

Hi, Solo is 1 evening of 3-minute solos, happening 2 times a year at Pieter Performance Space, Los Angeles. #9 was 9 artists, curated by Alexsa Durrans and Miles Brenninkmeijer, and took place on November 9, 2019.

solos by: Alana Frey, Autumn Randolph, Cheng-Chieh Yu (in collaboration with Sarah Jacobs and Darrian O’Reilly), Chris Emile, Christopher Argodale, Emily Lucid, Sebastian Hernandez, Simone Forti, Tamsin Carlson

Simone Forti on Alana Frey’s ‘Flour’ and Emily Lucid’s ‘Guardian Angel’

Hearts and Minds

Flour. A balloon is blown to size and fitted with a reed. Alana Frey, situated forward and to the side, her hands as if full of milk dripping from the fingers, eyes rolled back, is being played by the sound of the prepared balloon emptying, her internal energies simultaneously sinking and rising with the drone. When the air stops sounding the reed, the action will end.

Alana writes that this is a practice of the pelvis and that which dangles below and above it. Her attention is clearly inward on sensation but also on the concept, the focus and parameters of the piece.

The sound, too, is conceptual- as composer Jamie Green fills the balloon-horn with 4 and 1/2 breaths of air, which is equal to three minutes of body performing.

To make 3 Standard Stoppages, Marcel Duchamp dropped three one-meter-long threads from the height of one meter. The random curves they assumed upon landing were transferred to three wooden slats with edges shaped to match the curves of the threads. Thus, the alternate ruler.

Guardian Angel, (Choreography by Emily Lucid and performed by Emma James and Camilla Carper) could have taken place eons ago in a dark forest full of predatory beasts. The hunter-gatherers huddle around the campfire listening to this familiar song, “He called me a homosexual. Knocked me to the ground. He said, ‘Stay there for three minutes’”. And the song is about the beloved protecting angel. At one moment the angel rests her head on the singer’s shoulder.

I too have an angel, who one time kept me safe in a dark street on a late night when confronted by two muggers. The singing voice, full and familiar, brings sensation to the listeners’ hearts.

Simone Forti likes to juxtapose different elements, leaving energy space between them.

Alana Frey on Simone Forti’s ‘Window’

small call whenever there is air, or the presence of fate. the body is soft around the small stick of bamboo. if sound is wanting, it comes vibrating (i am familiar with this too).

air can be a hollow in the body. i think Simone is discreet, like this. air might whistle out. a clear passage, a window.

the feet are in black shoes, weightless in her wearing of them. an exquisite softness like this. there are no directions available to face. Simone not facing the wall, nor the audience, nor the corner. she does not meander and she is not casual. there, that occasional presence of sound. and that occasional presence of the feet in the shoes, on the floor. they are not planted, they are certainly not taking flight. they’re pretty good as is.

then, like window and how you can put your hand through when it’s open, and touch the glass when it’s closed, and it’s cold- the wandering ceases, the small bamboo is placed on the floor. the lights go bright.

a horizontal presentation and the slight smile from this, and the softening of face and attitude that must follow.

the horizontal presentation is: both arms go open. one to the left, one to the right. there is no extension or reach in it. nothing happening in the arms and hands to exclaim direction, but rather the Left and Right is indicated through Simone and the Action. still, a definite energy, an expansion, a burst even, when the arms go, out to the sides.

with arms go one foot and one leg, one at a time. right, together, left, together.

right: the right foot steps out to the right side and takes some weight so that the right knee bends and, because of this, the right arm appears more energetic than the left. that is subtle. then the right toe on the rubber sole of the black right shoe skims the floor, like a child might, towards “together.”

“together” means: where both feet and arms greet the body.

left: the left foot steps out to the left side and takes some weight so that the left knee bends and, because of this, the left arm appears more energetic than the right. then the left toe on the rubber sole of the black left shoe skims the floor, like a child might, towards “together.”

this does go. there is no Anatomy to speak of, but i still like to describe the movement and directions. this is a wonderful situation.

the bamboo is on the floor.

Alana Frey is currently at work with dance and sound. she is invested in a non-invested rigorous research practice of performance-making (or, letting performance make).

photos by Alexx Shilling

0 notes

Text

Zena Bibler and Barry Brannum on An Instance of This

[Editor’s note: In the spirit of Jennie Liu and Alana Frey’s reflections on Water Will by Ligia Lewis, Zena Bibler and I exchanged questions, notes, and insights about An Instance of This. We were both reeling after the performance — described as “an ephemeral micro-community” by creator-performers jose e. abad, Carlos Medina-Diaz, Justin Morris, and Randy Reyes — and wanted some time to process what we’d seen. What you see here is a lightly edited version of the ideas we generated together (via email) in the subsequent days. -BB]

BARRY: A lot of people we'd lump under the umbrella of 'postmodern improvisers' claim they're interested in the erotic. To what extent do you believe that's true? For yourself? For the work you're interested in? For this piece?

ZENA: A lot of things come up for me in response to this question. When I was watching An Instance of This, I remember thinking about an "erotics of giving oneself over." I actually scrawled it down in a little notebook in the dark. I'm thinking specifically of a moment early on in the piece when I saw Justin standing on top of the stairs, taking big bites out of a rose. His mouth was near a mic, so we could hear the crunch of the petals and hear him sort of fluff/spit/blow them out of his mouth onto Randy who was below on his hands and knees arranging little pieces of paper that Justin had dropped earlier. The petals floated down to the ground and Randy gathered them one by one, making them into a ring to encircle some other materials he had collected. Later Justin drank from a bottle of wine and spit it/dripped it/let it fall down onto Randy's back. It soaked his white shirt, which he removed, rung out, and added to the little altar he was making.