maybe if I collect enough references I'll actually make something

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

some words for worldbuilding (pt. 1)

Air

billow, breath, bubble, draft, effervescence, fumes, puff, vapor

Arena

aquarium, bazaar, coliseum, field, hall, mecca, stage

Building

abbey, architecture, armory, asylum, bakery, bar, booth, cathedral, club, construction, court, department store, dock, edifice, emergency room, factory, food court, fort/fortress, framework, garrison, greasy spoon, hacienda, hangout, headquarters, hotel, inn, institute/institution, jetty, laboratory, mansion, mental hospital, monastery, mosque, museum, nursing home, office, pavilion, penitentiary, plant, prison, rampart, repository, ruins, sanctuary, shrine, skyscraper, stockade, storeroom, structure, temple, theater/theatre, treasury, warehouse, wharf

City

capital, metropolis, town, village

Furniture

altar, banister, bench, booth, bunk, cabinet, chair, couch, crib, davenport, dresser, furnishings, futon, jetty, lectern, partition, perch, platform, pulpit, rail/railing, screen, secretary, stand, wardrobe

Geographic division

area, county, desert, dynasty, kingdom, outskirts, quarter, sector, suburb, territory, tract, zone

Habitat

abode, ecosystem, environmentalist, habitat/habitation, harbor, home, land, nest, paradise, premises, refuge, settlement, tent

Habitat, human: accommodations, apartment, barracks, cabin, castle, condominium, convent, domesticity, dungeon, element, encampment, estate, grange, hacienda, home, house, housing, hut, jail, lodging, madhouse, monastery, neighborhood, old country, palace, prison, reservation, resort, sanctuary, shanty, suite, vacancy, villa

Habitat, rural: barn, burrow, conservatory, desert, farm, forest, grange, jungle, sanctuary, wilderness/wilds, wood/woods

Land

abyss, avalanche, bank, bay, bed, bluff, campus, cape, cavern, cliff, compost, cove, crevice/crevasse, dirt, downgrade, dune, elevation, estuary, expanse, field, fossil, garden, glacier, gorge, green, ground, gulf, harbor, hillock, inlet, knoll, landscape, lawn, lot, marshy, menagerie, mine, moat, mound, mountainous, nature, outlook, park, patio, pit, plateau, plaza, porch, prairie, projection, property, quagmire, ravine, ridge, savanna, shelf, soil, stack, table, trench, tundra, valley, well, wood/woods, yard

Nation

country, home, land, nationality, soil, state

Personal item

adornment, amulet, beads, best-seller, briefcase, cache, cargo, charm, contraceptive, disguise, effects, equipment, favorite, gem, glasses, handbag, jewelry, knickknack, luggage, marionette, memorabilia, necklace, novelty, object d’art, odds-on-favorite, paraphernalia, pledge, possession, pride, puppet, purse, resources, ring, souvenir, stuff, supplies, sustenance, thing/things, trappings, trifle, valuable

Planet

cosmos, Earth, galaxy, moon, planet, sphere, world

Region

capital, commonwealth, quarter, region, settlement, suburb

Room

alcove, attic, bath, bedroom, boutique, cellar, den, enclosure, foyer, gin mill, hall, lavatory, loft, outhouse, parlor, restaurant, saloon, shop, stage, store, tenement, theater/theatre, vestibule

Shape

angular, beaten, billowy, checkered, concave, conical/conic, crescent, curly, deformed, elliptical, flat, gnarled, kinky, misshapen, obtuse, round, shapeless, spiral, straight

Vehicle

camper, conveyance, motorcade, transport

Vehicle, air: aircraft, armada, blimp, dirigible, helicopter, shuttle, UFO

Vehicle, land: ambulance, bicycle, car, cherry-picker, dolly, excavator, model, traffic, truck

Vehicle, water: armada, boat, craft, fleet, sailboat, yacht

Water

abyss, aqueduct, basin, beach, blackball, brook, cape, channel, condensation, creek, deep, estuary, fountain, gulf, heading, inlet, lake, oasis, pond, promontory, reservoir, sea, spray, strait, tide, wash, wave, whirlpool

NOTE

The above are concepts classified according to subject and usage. It not only helps writers and thinkers to organize their ideas but leads them from those very ideas to the words that can best express them.

It was, in part, created to turn an idea into a specific word. By linking together the main entries that share similar concepts, the index makes possible creative semantic connections between words in our language, stimulating thought and broadening vocabulary.

Source ⚜ Writing Basics & Refreshers ⚜ On Vocabulary

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Skip Google for Research

As Google has worked to overtake the internet, its search algorithm has not just gotten worse. It has been designed to prioritize advertisers and popular pages often times excluding pages and content that better matches your search terms

As a writer in need of information for my stories, I find this unacceptable. As a proponent of availability of information so the populace can actually educate itself, it is unforgivable.

Below is a concise list of useful research sites compiled by Edward Clark over on Facebook. I was familiar with some, but not all of these.

⁂

Google is so powerful that it “hides” other search systems from us. We just don’t know the existence of most of them. Meanwhile, there are still a huge number of excellent searchers in the world who specialize in books, science, other smart information. Keep a list of sites you never heard of.

www.refseek.com - Academic Resource Search. More than a billion sources: encyclopedia, monographies, magazines.

www.worldcat.org - a search for the contents of 20 thousand worldwide libraries. Find out where lies the nearest rare book you need.

https://link.springer.com - access to more than 10 million scientific documents: books, articles, research protocols.

www.bioline.org.br is a library of scientific bioscience journals published in developing countries.

http://repec.org - volunteers from 102 countries have collected almost 4 million publications on economics and related science.

www.science.gov is an American state search engine on 2200+ scientific sites. More than 200 million articles are indexed.

www.pdfdrive.com is the largest website for free download of books in PDF format. Claiming over 225 million names.

www.base-search.net is one of the most powerful researches on academic studies texts. More than 100 million scientific documents, 70% of them are free

247K notes

·

View notes

Text

writing advice for characters with a missing eye: dear God does losing an eyes function fuck up your neck. Ever since mine crapped out I've been slowly and unconsciously shifting towards holding my head at an angle to put the good eye closer to the center. and human necks. are not meant to accommodate that sorta thing.

62K notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any tips on identifying plot holes during revisions?

10 Tips for Identifying Plot Holes

1) Create a "Big Picture" Overview of Your Story

Whether you use a scene list, chapter by chapter summary, timeline, flow chart of events, or some combination of the above, having a "big picture" overview of your story allows you to see all the smaller parts and how they fit together. Not only can it help you spot problems as you're creating it, it also gives you something to follow as you're revising to help make sure everything makes sense.

2) Create a List of Plot Points and Subplot Points

Make a list of your story's plot points and subplot points. Once again, not only can the creation of this list help you spot potential problems, it will also be a crucial tool during the revision process as well as helpful for the next exercise.

3) Follow the Chain of Cause and Effect

Good continuity in your story means having a tight relationship between cause and effect. For each plot point and subplot point, you should be able to ask "why did this happen" and answer "because this other thing happened." You should also be able to look at each plot point or subplot point and say, "Because this happened, this next thing happens."

4) Look at Character Choices

Since stories are ultimately about people who want something trying to get that thing, plot points and subplot point are often the result of character choices and actions. So, for every choice a character makes or action they take, ask why? Did that choice make sense for that character's personality, situation, and back story? Did it make sense for that particular moment?

5) Make Sure Subplots Are Tied Up

Make a list of your subplots and make sure they're all tied up by the end. Pay attention to how and when they branched back into the story and what they accomplished.

6) Create Character/Setting Continuity Tables

Create a table of important characteristics like hair color, eye color, current age, birthday, etc. and when you're reading through your story, any time a detail like that comes up, check it in the table to make sure you've got it right. You can do the same thing for setting details.

7) Create a Technical Detail Checklist

For every technical detail you include in your story, whether that's the moon being out and in a certain phase in a particular scene, the amount of time it takes to travel a particular distance, how a particular weapon works, the ingredients of a particular spell or potion, the types of berries your character forages, an historical garment or costume... put it in a checklist. Then, when you're revising and you get to that item, double-check the details you've included in the actual story against your research (or look them up again), and check them off when you're sure they're accurate.

8) Create a "Things That Need Reviewing" Checklist

You can do the same while you're writing/editing for general things you want to double-check, like maybe you recall your character mentioning something about their childhood home in a chapter, and now they're saying something else about it and you want to go back later and make sure the two things are coherent.

9) Review Your Manuscript with Fresh Eyes

When you've been with your WIP for weeks or months or years, it becomes tough to see mistakes that would be obvious to anyone else. If you can, try stepping away from your manuscript for a few days or weeks so that you can come back to it with fresh eyes. Another trick you can use (especially if you can't step away for long or at all) is to change the font style and/or color in your manuscript. This can trick your brain into feeling like it's seeing everything for the first time. Reading it out loud or trying to to visualize it like a movie can also help.

10) Get Feedback from Other People

If you plan on posting or publishing your story anyway, it's crucial to get critical eyes on your story during your revision process. Critique groups, writing groups, critique partners, beta readers, and editors are all great ways to get feedback on your story before publication. These folks can help you spot problems, like plot holes and continuity errors, before you share, query, or publish your story.

I hope that helps!

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Have a writing question? My inbox is always open!

Visit my FAQ

See my Master List of Top Posts

Go to ko-fi.com/wqa to buy me coffee or see my commissions!

2K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I've been trying to plan for a novel, and I've come to a huge setback where I don't know how to fill in "gaps" in the storyline so that the pacing doesn't seem to rushed or too slow. Do you have any tips about how to pace a plot? Thank you!!

Pacing a plot…

As I’ve said in the past, pacing issues can usually be solved by examining the story’s subplots. Your subplots should be functioning as formative tools to the main plot line. Tracing their progression to find areas where you can utilize events to speed up, slow down, or reveal key information which balances the story is imperative to moving the story forward in a way that feels intentional and effective.

When you’re planning individual scenes, focusing on tone can help with pace more than you may assume. Eliciting certain feelings in the reader can make events seem faster or slower than they are actually moving in the timeline. The more exciting or intense a scene is in tone, the more the reader will think has occurred in a potentially short amount of in-universe time.

Pacing issues can also come about due to a lack of elaboration in key scenes or developmental moments. The story can feel rushed if important details seem to fall through the cracks, or too slow if you’re emphasizing insignificant description or explanation. Reviewing the scenes you’ve got and how they connect can reveal where you are lacking elaboration or where you can make cuts.

Here are a few resources you may find helpful…

Pacing Appropriately

Coming Up With Scene Ideas

Expanding Scenes

Tackling Subplots

A Guide To Tension & Suspense In Your Writing

Ways To Fit Character Development Into your Story

–

Masterlist

If you enjoy my blog and wish for it to continue being updated frequently and for me to continue putting my energy toward answering your questions, please consider Buying Me A Coffee, or pledging your support on Patreon, where I offer early access and exclusive benefits for only $5/month.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Giving Quality, Motivating Feedback

A guest post by @shealynn88!

The new writer in your writing group just sent out their latest story and it’s...not exciting. You know it needs work, but you’re not sure why, or where they should focus.

This is the blog post for you!

Before we get started, it’s important to note that this post isn’t aimed at people doing paid editing work. In the professional world, there are developmental editors, line editors, and copy editors, who all have a different focus. That is not what we’re covering here. Today, we want to help you informally give quality, detailed, encouraging feedback to your fellow writers.

The Unwritten Rules

Everyone seems to have a different understanding of what it means to beta, edit, or give feedback on a piece, so it’s best to be on the same page with your writer before you get started.

Think about what type of work you’re willing and able to do, how much time you have, and how much emotional labor you’re willing to take on. Then talk to your writer about their expectations.

Responsibilities as an editor/beta may include:

Know what the author’s expectation is and don’t overstep. Different people in different stages of writing are looking for, and will need, different types of support. It’s important to know what pieces of the story they want feedback on. If they tell you they don’t want feedback on dialogue, don’t give them feedback on dialogue. Since many terms are ambiguous or misunderstood, it may help you to use the list of story components in the next section to come to an agreement with your writer on what you’ll review.

Don’t offer expertise you don’t have. If your friend needs advice on their horse book and you know nothing about horses, be clear that your read through will not include any horse fact checking. Don’t offer grammar advice if you’re not good at grammar. It doesn’t mean you shouldn’t give feedback on things you do notice, but don’t misrepresent yourself, and understand your own limits.

Give positive and constructive feedback. It is important for a writer to know when something is working well. Don’t skimp on specific positive feedback — this is how you keep writers motivated. On the other hand, giving constructive feedback indicates where there are issues. Be specific on what you’re seeing and why it’s an issue. It can be hard for someone to improve if they don’t understand what’s wrong.

Be clear about your timing and availability, and provide updates if either changes. Typically, you’ll be doing this for free, as you’re able to fit it in your schedule. But it can be nerve wracking to hand your writing over for feedback and then hear nothing. For everyone’s sanity, keep the writer up to date on your expected timeline and let them know if you’re delayed for some reason. If you cannot complete the project for them, let them know. This could be for any reason — needing to withdraw, whatever the cause, is valid! It could be because working with the writer is tough, you don’t enjoy the story, life got tough, you got tired, etc. All of that is fine; just let them know that you won’t be able to continue working on the project.

Be honest if there are story aspects you can’t be objective about. Nearly all of your feedback is going to be personal opinion. There are some story elements that will evoke strong personal feelings. They can be tropes, styles, specific characterizations, or squicks. In these cases, ask the writer to get another opinion on that particular aspect, or, if you really want to continue, find similar published content to review and see if you can get a better sense of how other writers have handled it.

Don’t get personal. Your feedback should talk about the characters, the narrator, the plotline, the sentence structure, or other aspects of the story. Avoid making ‘you’ statements or judgements, suggested or explicit, in your feedback. Unless you’re looking at grammar or spelling, most of the feedback you’ll have will be your opinion. Don’t present it as fact.

Your expectations of the writer/friend/group member you are working with may include:

Being gracious in accepting feedback. A writer may provide explanations for an issue you noticed or seek to discuss your suggestions. However, if they constantly argue with you, that may be an indicator to step back.

Being responsible for emotional reactions to getting feedback. While getting feedback can be hard on the ego and self esteem, that is something the writer needs to work on themselves. While you can provide reassurance and do emotional labor if you’re comfortable, it is also very reasonable to step back if the writer isn’t ready to do that work.

Making the final choice regarding changes to the work. The writer should have a degree of confidence in accepting or rejecting your feedback based on their own sense of the story. While they may consult you on this, the onus is on them to make changes that preserve the core of the story they want to tell.

Some people aren’t ready for feedback, even though they’re seeking it. You’re not signing up to be a psychologist, a best friend, or an emotional support editor. You can let people know in advance that these are your expectations, or you can just keep them in mind for your own mental health. As stated above, you can always step back from a project, and if writers aren’t able to follow these few guidelines, it might be a good time to do that. (It’s also worth making sure that, as a writer, you’re able to give these things to your beta/editor.)

Specificity is Key

One of the hardest things in editing is pinning down the ‘whys’ of unexciting work, so let’s split the writing into several components and talk about evaluations you can make for each one.

You can also give this list to your writer ahead of time as a checklist, to see which things they want your feedback on.

Generally, your goal is going to be to help people improve incrementally. Each story they write should be better than the previous one, so you don’t need to go through every component for every story you edit. Generally, I wouldn’t suggest more than 3 editing rounds on any single story that isn’t intended for publication. Think of the ‘many pots’ theory — people who are honing their craft will improve more quickly by writing a lot of stories instead of incessantly polishing one.

With this in mind, try addressing issues in the order below, from general to precise. It doesn’t make sense to critique grammar and sentence structure if the plot isn’t solid, and it can be very hard on a writer to get feedback on all these components at once. If a piece is an early or rough draft, try evaluating no more than four components at a time, and give specific feedback on what does and doesn’t work, and why.

High Level Components

Character arc/motivation:

Does each character have a unique voice, or do they all sound the same?

In dialogue, are character voices preserved? Do they make vocabulary and sentence-structure choices that fit with how they’re being portrayed?

Does each character have specific motivations and focuses that are theirs alone?

Does each character move through the plot naturally, or do they seem to be shoehorned/railroaded into situations or decisions for the sake of the plot? Be specific about which character actions work and which don’t. Tell the writer what you see as their motivation/arc and why—and point out specific lines that indicate that motivation to you.

Does each character's motivation seem to come naturally from your knowledge of them?

Are you invested (either positively or negatively) in the characters? If not, why not? Is it that they have nothing in common with you? Do you not understand where they’re coming from? Are they too perfect or too unsympathetic?

Theme:

It’s a good idea to summarize the story and its moral from your point of view and provide that insight to the writer. This can help them understand if the points they were trying to make come through. The theme should tie in closely with the character arcs. If not, provide detailed feedback on where it does and doesn’t tie in.

Plot Structure:

For most issues with plot structure, you can narrow them down to pacing, characterization, logical progression, or unsatisfying resolution. Be specific about the issues you see and, when things are working well, point that out, too.

Is there conflict that interests you? Does it feel real?

Is there a climax? Do you feel drawn into it?

Do the plot points feel like logical steps within the story?

Is the resolution tied to the characters and their growth? Typically this will feel more real and relevant and satisfying than something you could never have seen coming.

Is the end satisfying? If not, is it because you felt the end sooner and the story kept going? Is it because too many threads were left unresolved? Is it just a matter of that last sentence or two being lackluster?

Point Of View:

Is the point of view clear and consistent?

Is the writing style and structure consistent with that point of view? For example, if a writer is working in first person or close third person, the style of the writing should reflect the way the character thinks. This extends to grammar, sentence structure, general vocabulary and profanity outside of the dialogue.

If there is head hopping (where the point of view changes from chapter to chapter or section to section), is it clear in the first few sentences whose point of view you’re now in? Chapter headers can be helpful, but it should be clear using structural, emotional, and stylistic changes that you’re with a new character now.

Are all five senses engaged? Does the character in question interact with their environment in realistic, consistent ways that reflect how people actually interact with the world?

Sometimes the point of view can feel odd if it’s too consistent. Humans don’t typically think logically and linearly all the time, so being in someone’s head may sometimes be contradictory or illogical. If it’s too straightforward, it might not ‘feel’ real.

Be specific about the areas that don’t work and break them down based on the questions above.

Pacing:

Does the story jump around, leaving you confused about what took place when?

Do some scenes move quickly where others drag, and does that make sense within the story?

If pacing isn’t working, often it’s about the level of detail or the sentence structure. Provide detailed feedback about what you care about in a given scene to help a writer focus in.

Setting:

Is the setting clear and specific? Writing with specific place details is typically more rooted, interesting, and unique. If you find the setting vague and/or uninteresting and/or irrelevant, you might suggest replacing vague references — ‘favorite band’, ‘coffee shop on the corner’, ‘the office building’ — with specific names to ground the setting and make it feel more real.

It might also be a lack of specific detail in a scene that provides context beyond the characters themselves. Provide specific suggestions of what you feel like you’re missing. Is it in a specific scene, or throughout the story? Are there scenes that work well within the story, where others feel less grounded? Why?

Low Level Components

Flow/Sentence Structure:

Sentence length and paragraph length should vary. The flow should feel natural.

When finding yourself ‘sticking’ on certain sentences, provide specific feedback on why they aren’t working. Examples are rhythm, vocabulary, subject matter (maybe something is off topic), ‘action’ vs ‘explanation’, passive vs. active voice.

Style/Vocabulary:

Writing style should be consistent with the story — flowery prose works well for mythic or historical pieces and stories that use that type of language are typically slower moving. Quick action and short sentences are a better fit for murder mysteries, suspense, or modern, lighter fiction.

Style should be consistent within the story — it may vary slightly to show how quickly action is happening, but you shouldn’t feel like you’re reading two different stories.

SPAG (Spelling and Grammar):

Consider spelling and grammar in the context of the point of view, style and location of the story (eg, England vs. America vs. Australia).

If a point of view typically uses incorrect grammar, a SPAG check will include making sure that it doesn’t suddenly fall into perfect grammar for a while. In this case, consistency is going to be important to the story feeling authentic.

Word Count Requirements:

If the story has been written for a project, bang, anthology, zine, or other format that involves a required word count minimum or maximum, and the story is significantly over or under the aimed-for word count (30% or more/less), it may not make sense to go through larger edits until the sizing is closer to requirements. But, as a general rule, I’d say word count is one of the last things to worry about.

*

The best thing we can do for another writer is to keep them writing. Every single person will improve if they keep going. Encouragement is the most important feedback of all.

I hope this has helped you think about how you provide feedback. Let us know if you have other tips or tricks! This works best as a collaborative process where we all can support one another!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Masterpost: How to write a story?

Compilation of writing advice for some aspects of the writing process.

How to motivate myself to write more

How to get rid of writer’s block

Basic Overview: How to write a story

How to come up with plot

How to create a character

How to make a character unique

How to start a story

How to write a prologue

How to write conversation

How to write witty banter

How to write the last line

How to write a summary

How to write a book description

How to write romance

How to write emotional scenes

How to write an argument

How to write yelling

How to write betrayal

How to title fanfiction

How to write an unreliable narrator

How to write character deaths

How to use songs in a fanfiction

How to name fictional things

Introducing a group of characters

Large cast of characters interacting in one scene

Redemption arc

Plot twists

Fatal Character Flaws

Good traits gone bad

More specific scenarios

Slow burn

AU ideas

Favourite tropes

How to create quick chemistry

How to write a bilingual character

How to write a character with glasses

How to create a villain

How to write a polyamorous relationship

How to write a wedding

How to write found family

How to write forbidden love

How to write a road trip

How to create and write a cult

How to write amnesia

How to write a stratocracy

How to write the mafia

Criminal past comes to light

Reasons for breaking up while still loving each other

Relationship Problems

Relationship Changes

Milestones in a relationship

Platonic activities for friends

Settings for conversations

Introducing partner(s) to family

Honeymoon

Date gone wrong

Love Language - Showing, not telling

Love Language - Showing you care

Affections without touching

Giving the reader butterflies with your characters

Reasons a couple would divorce on good terms

How to write enemies to lovers

How to write lovers to enemies to lovers

How to write academic rivals to lovers

How to write age difference

How to create a coffee shop atmosphere

How to write a college party

How to write modern royalty

Arranged matrimony for royalty

Paramilitary Forces/ Militia

Inconvenient things a ghost could do

A Queen’s Assassination Plot

Crime Story - Detective’s POV

Evil organization of assassins

Evil wins in the end

Causes for the apocalypse

Last day on earth

If you like my blog and want to support me, you can buy me a coffee or become a member! And check out my Instagram! 🥰

38K notes

·

View notes

Text

that whole "make your characters want things" does so much work for you in a story, even if what your characters want is stupid and irrelevant, because how people go about pursuing their desires tells you about them as a person.

do they actually move toward what they desire? how far are they willing to go for it? do they pursue their desires directly or indirectly? do they acquire what they desire through force, trickery, or negotiation? do they tell themselves they aren't supposed to feel desire and suppress it? does the suppressed desire wither away and die, or does it mutate and grow even stronger? is the initially expressed desire actually an inadequate and poorly translated different desire that they lack language for? does the desire change once the language has been updated, or when new experiences outline the desire more clearly? do they want something else once they have better words for it, or once they know that they definitely don't want something they thought they wanted before?

how does the world accommodate those desires? what does the world present to your character and in what order to update and clarify their desires? how does your magic system or sci-fi device correspond to those desires and the pursuit of them?

there's so much good story meat on those bones; you just have to be brave and decisive enough to let characters want specific things instead of letting them float in the current of the plot.

21K notes

·

View notes

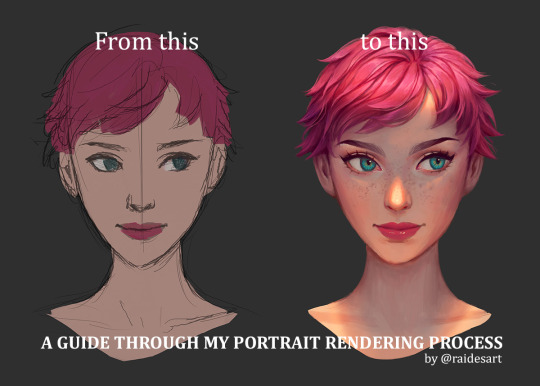

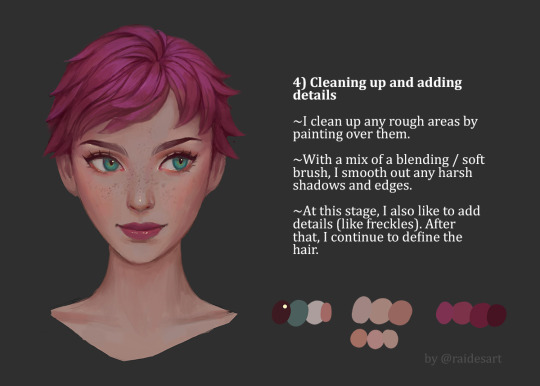

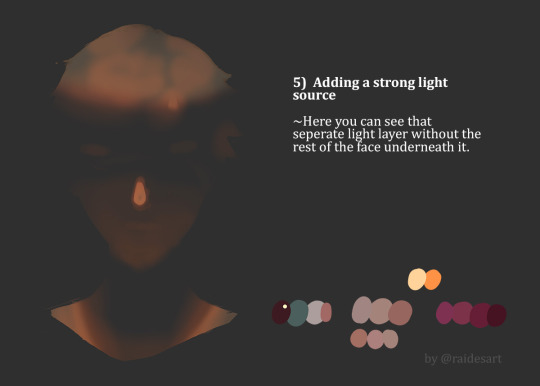

Photo

Throwback to this portrait tutorial that I made last year ^^ Do you find this helpful? If you are interested in learning more about my techniques and process, then feel free to check out more tutorials on my Patreon page! (link in bio)

13K notes

·

View notes

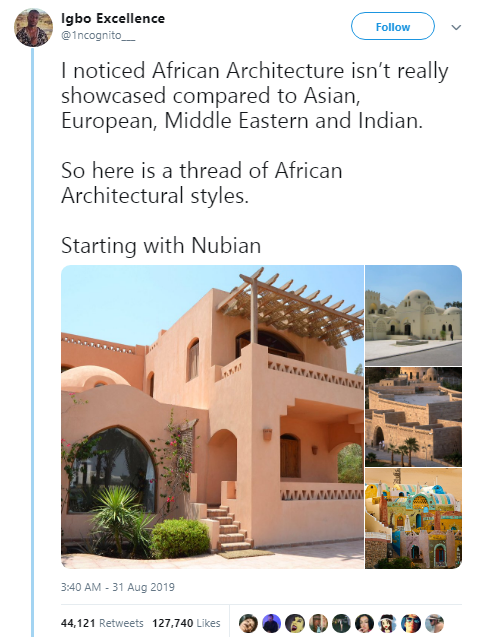

Photo

i feel like we don’t talk about things like this enough

314K notes

·

View notes

Text

A bit of incredibly straightforward writing advice I wish someone had given me years ago:

Suspense = unanswered questions in the reader’s mind

If you want to create suspense in your story, raise a question and delay the answer. You can do this on the story-level by raising what’s called a “story question” (Will Jack find the murderer?), but you can also do it on the scene or sentence level. And the questions don’t have to be big, either. Witness the tantalizing glory of simply withholding some basic information in the first line of a scene:

After twenty years of truffle-hunting, I thought I knew everything. But what I found in the forest that day deeply disturbed me. I’d never seen anything like it.

At this point, the reader’s like, HOLY SHIT WHAT IS IT?? You’ve dangled a question, they want the answer, and they’ll probably feel anxious until they get it. That’s suspense. Want to keep it going? Delay gratification.

Around noon I noticed something shiny sticking up from the mossy leaves around an old oak tree a few miles from the lake. Instinctively, I patted my holster: My pocket knife hadn’t fallen out, and my satchel of coins was also accounted for. I bent down, squinting. The jagged shard of metal glinted blue, then red. It seemed to be vibrating, too, as if it had an electrical charge.

WHAT IS IT HOLY FUCKING CRAP WHAT IS IT????

There’s a bit of an art to this, of course. You’ll eventually want to answer this question, then raise another. Generally, smaller questions (what’s that shiny thing in the leaves?) deserve quicker answers than bigger ones (will Keith and Jeremy fall in love?). You’ll need to experiment with proportion; feel out how many unanswered questions is too many (readers can only hold so many questions in their minds at a time), how to toggle between plot lines, when something is deserving of suspense and when it is not, etc. But the overall principle is really basic and adaptable.

Hope this helps.

1K notes

·

View notes

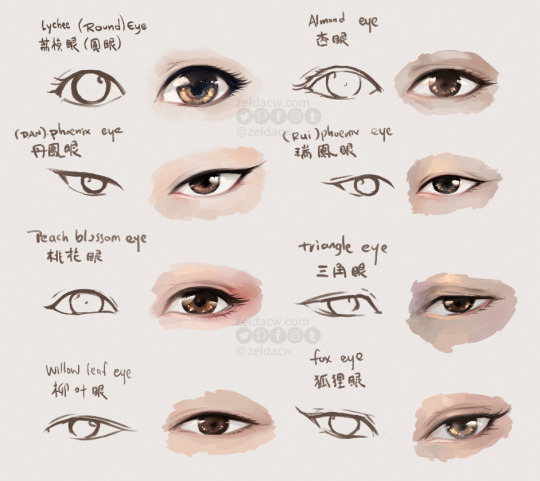

Photo

I sketched various eye shapes that were often mentioned in Chinese literature :3

♥ Read my comic | zeldacw on Patreon | Shop for prints & more ♥

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

When your Character...

Gets into: A Fight ⚜ ...Another Fight ⚜ ...Yet Another Fight

Hates Someone ⚜ Kisses Someone ⚜ Falls in Love

Calls Someone they Love ⚜ Dies / Cheats Death ⚜ Drowns

is...

A Child ⚜ Interacting with a Baby/Child ⚜ A Genius ⚜ A Lawyer

Beautiful ⚜ Dangerous ⚜ Drunk ⚜ Injured ⚜ Shy

needs...

A Magical Item ⚜ An Aphrodisiac ⚜ A Fictional Poison

To be Killed Off ⚜ To Become Likable ⚜ To Clean a Wound

To Find the Right Word, but Can't ⚜ To Say No ⚜ A Drink

loves...

Astronomy ⚜ Baking ⚜ Cooking ⚜ Cocktails ⚜ Food ⚜ Oils

Dancing ⚜ Fashion ⚜ Gems ⚜ Mythology ⚜ Numbers

Roses ⚜ Sweets ⚜ To Fight ⚜ Wine ⚜ Wine-Tasting ⚜ Yoga

has/experiences...

Allergies ⚜ Amnesia ⚜ Bereavement ⚜ Bites & Stings ⚜ Bruises

Caffeine ⚜ CO Poisoning ⚜ Color Blindness ⚜ Food Poisoning

Injuries ⚜ Jet Lag ⚜ Mutism ⚜ Pain ⚜ Poisoning

More Pain & Violence ⚜ Viruses ⚜ Wounds

[these are just quick references. more research may be needed to write your story...]

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Notes & References

Alchemy ⚜ Antidote to Anxiety ⚜ Attachment ⚜ Autopsy

Art: Elements ⚜ Principles ⚜ Photographs ⚜ Watercolour

Bruises ⚜ Caffeine ⚜ Color Blindness ⚜ Cruise Ships

Children ⚜ Children's Dialogue ⚜ Childhood Bilingualism

Dangerousness ⚜ Drowning ⚜ Dystopia ⚜ Dystopian World

Culture ⚜ Culture Shock ⚜ Ethnocentrism & Cultural Relativism

Emotions: Anger ⚜ Fear ⚜ Happiness ⚜ Sadness

Emotional Intelligence ⚜ Genius (Giftedness) ⚜ Quirks

Facial Expressions ⚜ Laughter & Humour ⚜ Swearing & Taboo

Fantasy Creatures ⚜ Fantasy World Building

Generations ⚜ Literary & Character Tropes

Fight Scenes ⚜ Kill Adverbs

Food: Cooking Basics ⚜ Herbs & Spices ⚜ Sauces ⚜ Wine-tasting ⚜ Aphrodisiacs ⚜ List of Aphrodisiacs ⚜ Food History ⚜ Cocktails ⚜ Literary & Hollywood Cocktails ⚜ Liqueurs

Genre: Crime ⚜ Horror ⚜ Fantasy ⚜ Speculative Biology

Hate ⚜ Love ⚜ Kinds of Love ⚜ The Physiology of Love

How to Write: Food ⚜ Colours ⚜ Drunkenness

Jargon ⚜ Logical Fallacies ⚜ Memory ⚜ Memoir

Magic: Magic System ⚜ 10 Uncommon ⚜ How to Choose

Moon: Part 1 2 ⚜ Related Words

Mystical Items & Objects ⚜ Talisman ⚜ Relics ⚜ Poison

Pain ⚜ Pain & Violence ⚜ Poison Ivy & Poison Oak

Realistic Injuries 1 2 ⚜ Rejection ⚜ Structural Issues ⚜ Villains

Symbolism: Colors ⚜ Food ⚜ Numbers ⚜ Storms

Thinking ⚜ Thinking Styles ⚜ Thought Distortions

Terms of Endearment ⚜ Ways of Saying "No" ⚜ Yoga

Compilations: Plot ⚜ Character ⚜ Worldbuilding ⚜ For Poets ⚜ Tips & Advice

all posts are queued. will update this every few weeks/months. send questions or requests here.

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

Full offense but your writing style is for you and nobody else. Use the words you want to use; play with language, experiment, use said, use adverbs, use “unrealistic” writing patterns, slap words you don’t even know are words on the page. Language is a sandbox and you, as the author, are at liberty to shape it however you wish. Build castles. Build a hovel. Build a mountain on a mountain or make a tiny cottage on a hill. Whatever it is you want to do. Write.

146K notes

·

View notes

Text

You will not use AI to get ideas for your story. You will lie on the floor and have wretched visions like god intended

151K notes

·

View notes