Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Day 15: Period

I’m on my period. I also have lost count of what day it is.

The break from fasting and praying is a welcomed one. I would be ashamed to say that, if it wasn’t for the struggle I’ve been experiencing in both those areas for the last week or so (let’s keep it real, since the beginning of Ramadan).

I’m also pretty sure this is the first time that I feel this type of relief from getting my period (during Ramadan). We’ve talked about this before. Besides the fact that my menstrual cramps take away any feeling of “vacation” (due to the fact that they are excruciating), there’s the added social stigma of being a woman on her period - especially during Ramadan. All of a sudden, you’re forced to hide away, to sneak about, to make yourself invisible so as not to offend the sensibilities of those around you with your dirty, faatra status.

I won’t lie, in the past, I fed into this narrative - that I should keep my shameful situation a secret; that I should keep my eating to a minimum, and out of sight (and, when I was younger, that I shouldn’t eat at all). But my period is not the type that can be hidden. Screaming in agony, vomit, losing consciousness - these are all things that can hardly be done discretely. So eventually, I gave up. And luckily, the men in my family (my father and brothers) are enlightened enough to not make me feel like crap for this thing I have no control over and this rule I didn’t make.

But outside the comfort of my home is a different story. In the (Muslim) world and on the internet, the Oppression Olympics torch burns bright. “Don’t eat around us, you’re hurting our fast! Have you no heart? How rude!” “Women say that men are weak when it comes to fasting, but we’re not the ones who get to have a break in the middle of the month!”

I’m rolling my eyes.

There are two types of folks who make this “it’s just your period” argument: men who don’t have a strong grasp of biology, and women who don’t get cramps (those unicorns). The rest of us understand the physical, hormonal, emotional and mental overhaul that accompanies menstruation.

But even if we were to assume that being on your period is this fun, relaxed, carefree time - to say that seeing me nibble on a sandwich or take a swig of water “hurts your fast” and ruins your life is more of a statement about you than it is about me. Part of the jihad (and, dare I say, the point) of fasting and Ramadan is to exercise self control, to take charge of your body and mind, to test your will.

Consider my non-fasting self part of that test. And if you have a problem with it, take it up with God.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 11: “وصف لي”

Have you heard of it?

It’s a Sudanese Facebook community, much like Craig’s List (does that still exist? I might be old), where folks living in Khartoum post their inquiries on where to get this or that. The range of “this or that” is wide - anything from the best place to fix your Nokia phone, to “I’m looking to buy a newborn Siberian Husky - any sellers?”

A few weeks ago, a man posted asking about where in Khartoum he could find ballet classes in which to enroll his daughter. His post ended with, “When I was her age, I was selling lemons in the souq, lol, how times change!” I chuckled at the observation, and was touched by this father’s desire to make his daughter’s wish come true.

My amusement and admiration, however, was short lived. The comments flowed underneath the post like a raging river of negativity and unnecessary aggression.

“Astaghfirullah, instead of teaching your daughter something useful like Quran, you want to teach her ballet??”

“Where have all the real men gone? This guy actually wants his daughter to become a dancer!” (English doesn’t do the negative connotation of the word رقاصة justice)

The comments became increasingly angry and disrespectful, until this:

“A3uthu billah! [I don’t know you but] this post made me hate you.”

I had to stop reading after that (I don’t know why I never learn to just not read the comments).

That post, like I said, was a few weeks ago, but I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I was confused; what about this post made people react this way? How is this man (a stranger to them) wanting to sign his little kid up for dance class a reflection of his masculinity, of his piety, of his decency as a human being? And even if it was, how is that anyone’s business? What gives them - random strangers in a Facebook CLASSIFIEDS group - the right to judge him in this way?

More than that, it was aggravating (though not surprising, unfortunately, this isn’t even the only post in this group that has devolved in this way) to see people use their alleged religiosity as a gateway and tool to be vile and abusive - and for something as petty and insignificant as this. Since when is it Islamic to berate and insult people? Is it not part of the instructions of our deen to be kind, compassionate and respectful to one another?

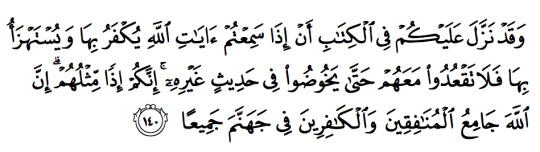

Last week, as I was reading through surat AlNisa (back when I could actually read), I came across this verse, and it immediately reminded me of that post:

And it has already come down to you in the Book that when you hear the verses of Allah [recited], they are denied [by them] and ridiculed; so do not sit with them until they enter into another conversation. Indeed, you would then be like them. Indeed Allah will gather the hypocrites and disbelievers in Hell all together. [verse 140]

If when folks are ridiculing the actual word of God, we are told to just get up and walk away until they change the subject, what in the name of everything good and holy makes you think that you can curse a man for asking about ballet classes for his kid?

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 10: Slipping

So, I’ve been absent. If you noticed, you’re really sweet; and if you didn’t, you’re really sweet.

I spiraled shortly after writing my last post. Actually, it’s more accurate to say that I’m still in mid-spiral, and it’s not exactly because of what I wrote on Day 7, although I’m sure it has a lot to do with it.

My anxiety has been in a state of flux the last few months; it is consistently there, but some days are “lighter” than others. When Ramadan started, I thought that this could be a time for me to experience some relief from it - and for the first week, I kind of did. But the more triggers occurred, the less I was able to control it, and the less I was able to function.

By Day 8, I was starting to feel my resolve drop. It became more difficult to be in the spirit. I began to lose concentration during prayer more easily, which I didn’t really pay much attention to since my ability to focus on tasks has been severely compromised for the last few months that my anxiety has been at its highest (even now, it is very, very difficult to focus on writing this). But the two pages of Quran I read per rak3a became increasingly difficult to get through. This was particularly frightening, because I couldn’t understand why all of a sudden I was unable to read. I became so distraught by this that I gave up reading the pages, and went back to just reciting small surahs to get me through prayer. In fact, I stopped reading Quran altogether.

Yesterday, I received an urgent job from a client, and was so frustrated with my lack of focus that I started to smack my head, harder and harder, until I had developed a headache. Halfway through the job, I felt tears well up in my eyes. (I didn’t cry)

And therein lies my dilemma. We are told that the best cure for anxiety is spirituality - reconnecting with the higher power, engaging in deep acts of worship to recenter our minds and spirits. In a Muslim’s case, you achieve this through your khushoo3 in prayer, through zikr, through reading the Quran. But what do you do when you can’t do any of those things? When you physically can’t?

I keep trying to read Quran - the least 3ibada I can do - and each time as soon as I look down at the page, fear bubbles up to my throat. My heart races, the page becomes blurry. I shake my head, close my eyes, open them again and wait for them to focus. The writing looks like a completely different language. I trip and stumble over the words, I come to a complete stop, staring intently at the page, trying to figure out what the grouping of letters makes, and with each delay in my reading, with each mistake I am hit with another wave of anxiety, of frustration, of fear, of shame.

I am at a point where everything has become a trigger that exacerbates my anxiety. In a WhatsApp conversation, someone sent me a fun “Where’s Waldo” type image. The wave of fear washed over me once again (I’ve lost count of how many times it has hit me today). I closed the image, and responded: “I can’t. It makes me nervous. Everything makes me nervous these days.”

Perhaps the worst part of all this is how it affects my interaction with the people around me - my family. To them, I am tense, cranky, mean. They don’t understand why.

Neither do I. And it scares me.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 7: “Deen” II

I feel like I didn’t say everything I wanted to say in yesterday’s post. Actually, I feel like I censored myself from saying everything I wanted to say - perhaps because I was afraid of how it would come off, but more likely because I felt uncomfortable putting it in writing and thus officially admitting it to myself.

I believe. But deen scares me.

It terrifies me. It feels unattainable, a mirage I keep chasing and every time I come close it slips through my fingers and dissipates from view. Most of the time, I feel like it doesn’t belong to me, that all my attempts to claim ‘ownership’ of it (for lack of a better term) would fail because, at the core, I feel like I’m not worthy. I worry that I am beyond redemption; one of those people described in the Quran as being plunged deeper in their waywardness and destined for hell.

Deen has never been easy for me, not for a single day in my life. I watch as others walk the tightrope with such ease, flipping and spinning and reveling in the joy of it. They talk about the lightness it brings. Meanwhile, I feel bogged down by the burden of it, clinging on to the rope for dear life, my fingers straining under the weight, slipping off one at a time, until I drop into the abyss of hopelessness, from which it takes me months to crawl back out.

Committing to prayer is hard. Actually, it’s physically painful. Duaa is impossible - I don’t know what to say, how to say it, I get tongue tied, I put my hands up and I’m speechless, my mind blank. By the end of it, I feel humiliated and defeated. Ironically Ramadan, with all its difficulty, is the one time I feel remotely secure in the deen. Something about the season makes it somewhat less agonizing to follow the rules and commit. I don’t know why, I just know it’s not because my “demons” are locked up. I’ve long since dispelled that theory - I know full well that the problem is me.

I watch how other people around me live. I tally and rank their actions. I spend hours considering where they would land on the deen scale. Then I hold myself up for comparison. I know that all of this is time wasted, that none of their actions will help me on the day that counts, that I won’t be compared to anyone but myself. That terrifies me more.

I try to think of the possible reasons why this is so difficult for me. Maybe I was made this way. My brain drifts back to those eternally wayward people referenced in the Quran, rendered deaf and blind to sense and redemption by Allah for their disobedience. Maybe, as they were, I’m meant to be an example, a lesson for someone else. But where does that leave me? I think about all the different times that example was mentioned in the Quran. I think about all the times the steps to redemption are mentioned in the Quran. So why weren’t those people given another chance to redeem themselves? Is my inability to commit to the straight and narrow a sign that I, too, have used up all my chances?

I’m not a bad person. I treat people with respect. I take care of my family. I try to do what’s right, to stand up for what’s right. But I’ve made some mistakes - big ones. Unforgivable ones, as I’m told. And I guess they are, because I can’t seem to forgive myself. Everything around me tells me my goodness isn’t enough. It won’t save me.

But I haven’t wronged anyone but myself. What about people who wrong others? Who hurt others? What about the people who have hurt me? Do they get redemption for what they’ve done?

I’m back to comparing. It doesn’t matter. It’s not about them. It’s about me.

I’m terrified of hell, and every day I’m more and more sure that I’ll end up there.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 6: “Deen”

(Let’s just pretend I wasn’t absent yesterday)

The extent of my “formal Islamic schooling” was until 5th grade. After that, we moved out of Sudan and my parents took over. Looking back, I’m surprised that my parents didn’t enroll me in an Islamic Sunday-school type program while we were abroad. Did it not exist where we lived? Were my parents aware of the dangers and preferred to have control over my religious education? Who knows.

I mean, they know, and I could probably ask them, but like... yeah.

In Sudan, 7issat aldeen/tarbeya islaamiya [Religion class/Islamic Education] was where two terror-filled worlds collided: on the one hand, you had the fear-driven general education system, where students were taught via threat and violent punishment; on the other, a carefully formulated strategy of “piety through fear” - i.e. scaring kids to death and (thus?) making them into good little Muslims.

It is probably for this reason that I don’t remember much if anything of what I was taught during those first five years of schooling. I truly believe that my brain repressed all that information because it came with some traumatizing experiences. In the only memory I remember vividly (perhaps it was too traumatic to repress), third or fourth grader me is spending all Friday (at that time, the only day off in the week) memorizing a particularly long surah for class. On Saturday, I recited the surah perfectly (fear is a powerful motivator). I was one of only 5 kids to have fully memorized the chapter. Our teacher marched us out into the courtyard, where the principal of our school (a large, heavy set man who was notoriously vicious) was waiting for us, horsewhip [sot 3anaj] in hand. We were all whipped that day, including those of us who had done the assignment and passed the test.

Unfortunately, this strategy of terror hasn’t changed with time; a few years ago, my uncle was telling my father and I about his daughter (a third grader at the time) who was having nightmares because of how vividly Jahannam (hell) was described to her in class, and all the ways the teacher said they would end up in hell.

But it’s not just school; God and religion are often used to strike fear in children of all ages at home, as a means to persuade, discipline, control - which is what makes it confusing to me when I see folks wonder why their children might have an aversion to religion, or have a hard time following “the straight and narrow”. It seems that in their desperate attempt to pass on these tenets and values of our deen, they forget some the directives Allah gave Sayyidna Mohammed (pbuh) to do the very same (in bold below):

There shall be no compulsion in [acceptance of] the religion. The right course has become clear from the wrong. So whoever disbelieves in Taghut and believes in Allah has grasped the most trustworthy handhold with no break in it. And Allah is Hearing and Knowing. (Al-Baqarah, verse 256)

So by mercy from Allah, [O Muhammad], you were lenient with them. And if you had been rude [in speech] and harsh in heart, they would have disbanded from about you. So pardon them and ask forgiveness for them and consult them in the matter. And when you have decided, then rely upon Allah . Indeed, Allah loves those who rely [upon Him]. (Ali Imran, verse 159)

It wasn’t until college that I gathered up the interest, courage and motivation to try (formally) learning about Islam again. I joined the MSA and became heavily involved. But even then, it was soured by my experiences within the organization as a non-hijabi and, in many ways, a non-Islamic school trained Muslim. They were things that I didn’t know; for example, that folks just didn’t shake hands with the opposite sex. I grew up with the understanding that only Ansar Sunna did that, but after being left hanging while others whispered in shock around me a few times, I realized that this was “the norm in America”. People’s less than kind (to put it mildly) reactions to me and my ignorance on various other points of ‘Muslim etiquette’ put me off, and I retreated once again.

There’s also the issue of racism within the Muslim community in America (and other places, I’m sure), which keeps folks like me from joining Islamic spaces like mosques, classes or conferences. And from what I’ve seen and heard from people about their experiences in Islamic schools, it makes me immensely grateful that my parents never enrolled me in these institutions. To give some context, check out this Twitter thread that a Latina Muslimah shared a couple of days ago. Here is an excerpt:

I don’t know if I have a point to this. I just wish that deen wasn’t so linked to fear, damnation and shame in my mind.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 4: Amr Khaled

My earliest memory of famous Egyptian TV preacher Amr Khaled: I am 14 or 15 years old, on vacation in Khartoum, sitting in a room full of my cousins watching TV. Scratch that, my earliest memory was a day or two before that. My cousins were engaged in a fervent discussion about some things he had said. I had no idea who they were talking about, and was too embarrassed to ask - inquiring about anything remotely tied to religion, especially as a mughtarib [emigrant], would often result in ridicule and tacit judgement of your piety.

Thankfully, I didn’t have to, because a day or two later I watched as my cousins sat huddled around the television, mesmerized by the man on the screen. There sat Amr Khaled, looking intently and lovingly at the camera (/studio audience?), and telling the story of Sayyidna Mohammed (pbuh). At one point, his voice cracks (later, I would discover that this happens quite often), and in my studio audience, someone got teary-eyed. It was fascinating.

Amr Khaled was my introduction to the “youth-friendly”, ‘celebrity’ sheikh, who spoke in colloquialisms and dressed in “regular clothes”. He was a far departure from what young Muslims across the Middle East were used to seeing: solemn-faced sheikhs draped in abayas with large, intimidating beards who spoke in a fear-inducing mélange of ayaat and fus7a [formal Arabic]. Amr Khaled smiled. He laughed. He cried. And though he too was assigned a larger than life quality by his followers, he was still human.

But I just wasn’t convinced; perhaps because I couldn’t understand him (his Egyptian accent and [now trademark] speech impediment). Or maybe it was because anything relating to deen terrified me no matter how it was packaged. In any event, the fandom that my cousins displayed made me uncomfortable, and seemed somehow inappropriate, so all their efforts to “put me on” and bring me into the fold were unsuccessful.

Yesterday, Amr Khaled’s name and likeness appeared on my Instagram feed, in the form of the following:

youtube

In case you can’t view the video, it shows Amr Khaled featured in an advertisement for chicken. In it, he addresses all the “shabab w banat” [guys and gals], urging them that “this Ramadan, we want to do everything right: we want to fast right, we want to worship right, and we want to eat right!” He goes on to introduce Asia Osman, a chef/nutritionist/something (it doesn’t matter). A little later in the ad, he tells Asia, “I want to give you a spiritual tip: they say that when you’re fasting, it is not just your stomach that is fasting; every part of you is fasting as well. Your eyes are fasting from what is haram, your mouth is fasting from what is haram, your ears are fasting from what is haram.”

He then declares, “With Asia’s recipes, inshallah, your meeting with Allah during Taraweeh and in qiyam alleil [late night worship] will be much sweeter!”

<cue public outrage>

As you can imagine, the ad was pulled, and Amr Khaled issued an apology, saying “Allah knows my intention”. And it’s true, only He knows his true intention behind what us mere mortals naturally interpret as a flagrant use of his influence and ‘religious clout’ to sell chicken.

As an adult, my issue with TV preachers and religious scholars is the result of years of trauma (which I wrote about here), as well as years of disappointment in the face of incidents such as these. For Amr Khaled to use his position as a spiritual teacher and leader in this way is disgusting and - sadly - predictable.

Once again, their inflammatory actions set their soapboxes alight, and we are reminded that they are just like us: mere men.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 3: Tilawa

Every year, I do my best to achieve at least one khatma [complete reading of the Quran] during Ramadan. In general, my technique for reading it has always been the same: to recite along with a qaari [reciter] in my ear. This is for several reasons:

1. I hate the sound of my own voice: why listen to my shaky, grating, unmelodious voice when I could listen to someone whose voice was blessed to unlock the heart and fill the soul with the word of God?

2. Reciting the Quran is hard: I know what you’re thinking, “it’s probably your shoddy Arabic.” But I promise you, it isn’t (just) that. Reading through the Quran with perfect pronunciation, taking into account all the tashkeel and recitation prompts, is difficult. People go to school for it, they study it. So reading along with a professional qaari acts as a pleasant guide to correct recitation (especially for someone like me who suffers from social anxiety and doesn’t wish to experience the terror of stumbling over the words in front of others in a class setting). There are surahs [chapters] such as AlKahf that I can now read correctly (I wanted to say perfectly, but like, lol, let’s not get carried away) thanks to repeated reading with the help of the qaari (Mishari Rashid got me togetherrrrr).

3. I am still intimidated by the Quran: yes, at my big age. When I was younger, and my mother was trying to convince me to read the Quran more, she said something that was supposed to make me feel better but instead left an indelible imprint on my mind. My mother told me that when she was younger, she was afraid of reading the Quran because of “the great responsibility of handling the word of God” (I wrote about this incident before). If my mother, the woman whom I regarded as the epitome of piety, whom I considered a veritable saint, felt unworthy to hold these words in her mouth, then who was I to even try? The first few Ramadans that I attempted to read through the Quran, I would be overcome with anxiety and would give up after just a few aayat [verses].

This year, however, I have decided to take the plunge and go solo. My goal is to complete at least one khatma unaided, for several reasons:

1. I need to challenge myself: yes, it’s difficult, but I need to train myself to read unassisted, otherwise I will forever be intimidated. You might argue (as I have many times with myself), what’s the problem with always listening to a qaari while you read? There isn’t, except how old did I say I was? That. Also, see #3 below.

2. I’m too old to be scared: like, seriously? Get it together. Ironically, my fear of the power of the Quran (and my clumsy tongue’s inadvertent disrespect of it) is keeping me from experiencing the advantages of that same power. (As you may have noticed, my life is full of cyclical dilemmas.)

3. It helps with focus: yes, it’s about reciting correctly, but it’s also about the words themselves. It’s about absorbing what’s being said, and with a qaari to lull me into a false sense of confidence - and literally lull me through the surah - I feel like I’m missing out on many more moments of connecting with the text. One of the awe inspiring qualities of the Quran is the beauty of its language, the poetry in its phrasing (I explored this briefly before). It is one that, as a writer, I am constantly drawn to and amazed by. But sometimes, it’s also in the details, the (comparatively) insignificant descriptions that make me stop and think, “Wait, is that where that came from?”

For example :

“Here you are loving them but they are not loving you, while you believe in the Scripture - all of it. And when they meet you, they say, "We believe." But when they are alone, they bite their fingertips at you in rage. Say, "Die in your rage. Indeed, Allah is Knowing of that within the hearts." [Aali Imran, verse 119]

If you are Sudanese, you know what it is to bite your fingertips in rage. All of our mothers have, at one point or another, done this to signal that they have reached the outer limits of their patience with our behavior (almost exclusively the index finger). I myself have bitten many a finger when faced with some of the unnecessary and infuriating things my little nieces do.

As I read through Aali Imran today, I stopped at this aaya and exclaimed, “Wait, is that where we got it from??”

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 2: Adjustment

I physically felt it, the exact moment I had tipped the scales, entering the danger zone of post-iftar incapacitation.

I had just finished the sambuksa pinned between my fingers, and took a long sip from my water bottle. Something told me to stop, but the sensation of perfectly chilled liquid rolling down my parched throat was too sweet to cut short.

And then it happened.

Something cold and not weightless, the size of a pebble found at the bottom of a stream, suddenly lodged itself in my stomach. I stopped, raising my head with a surprised jerk. “Uh oh”.

In a matter of seconds, the pebble grew outwards, assuming an oblong shape, and began fighting my diaphragm for its turf.

“I shouldn’t have had that water...”

My mother, who was sitting beside me and had already warned me yesterday not to overdo it with the liquids, ignored my pitiful expression of regret.

Almost 34 years old, with what I can confidently estimate at over 25 years of experience in fasting, and I still haven’t figured out a solid strategy to do Ramadan right.

The month is an upheaval: for 29-30 days (depending on the moon), you must readjust to a whole new mode of living. For 14-21hours out of each of those days (depending on where you live and the season), you must eliminate all sustenance from your life, making it not only a physical adjustment, but also a complete revamp of your daily routine. The food breaks that give your day structure are now gone, leaving you twisting in the wind with all this extra time (which, of course, feels like double the time when you’re hungry and thirsty).

Of course, I’m not even mentioning all the other behavioral adjustments you should make. One at a time.

But anyway, ideally you would repurpose the extra minutes of your day not encumbered by food or drink to work on some of your spiritual goals. And even if you didn’t, you could always take advantage of the (alleged) clarity that fasting provides to achieve more - professionally, academically, whatever.

I don’t think I ever give myself enough time to experience this mental clarity. Half a task in, I start to think about how tired I should be right now (regardless of how I actually feel). I convince myself that a nap is what I need. I convince myself that what I should actually do is work after fatoor. Energized by the nap and food, I will surely fly through my tasks, and even find some time late into the night to dedicate to pure, uninterrupted, focused ibada [worship].

Tonight, 750 milliliters into fatoor, I experienced what I can only describe as brain death. It’s now been an hour and a half since I began writing this post. I haven’t prayed Isha yet. I don’t even know if I’m going to be able to pray Taraweeh. At least twice, my mother has called my name, concern audible in her voice. “Malik mutanni7a kida?? Are you okay??” [Why are you staring off into space like that]

It’s because I can barely function, Mother.

I pride myself on not being “one of those people who just sees Ramadan as a time to obsess about food” - and it’s true. I’ve never found it difficult to adjust to the hunger, and I’m always amazed at how this season turns into a challenge on how many dishes one can make, how many types of juice will be available, how much we can eat and for how long.

Because it’s not just about the food. But in my smugness, I fail to realize that I have adjusted to no other aspect but the food, effectively still making it just about the very thing I said it wasn’t.

Welp.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 1: Euphoria

I don’t remember the last time I started my day with anything less than a scowl. But this morning, I woke up like a Disney princess - facial muscles relaxed, body light, eyes fluttering. Yes, the heart palpitations from what is now a 13-day anxiety attack were still there, but I didn’t feel like I was going to throw up, and that is a victory. Alhamdulilah.

The whole day just seemed to fly past (in a good way). The hunger was minimal, the thirst was just noticeable enough to remind me I was fasting, without being strenuous or bothersome. I’m doing this, I said to myself. This must be that elation people feel about Ramadan, and I’m feeling it. I’m one of them, now. One of the pious ones.

In my defense, I didn’t use that exact term. But yes, at some level, that is how I felt. Because it’s what I’ve been striving for. I still yearn to experience the excitement others exude at the approach of Ramadan (and if this sounds familiar, it’s because I’ve probably written about it in the previous years - hence the italicized “still”). I want to feel deserving of Ramadan, as opposed to being confronted with it.

Last year, I wrote about Ramadan being another opportunity I desperately needed to realign myself with the right path, to bolster my commitment and basically get my spiritual self together. I’m disappointed to report that nothing has changed, that once again I find myself standing in front of the mirror of this blog with a sheepish look on my face and my head hanging low. I’d laugh at the Groundhog Dayness of it all, if it wasn’t so disgraceful.

“And seek help through patience and prayer, and indeed, it is difficult except for the humbly submissive [to Allah]”

This afternoon, as I struggled to get through my daily couple of juzus (more on that struggle tomorrow), I came across the above aya, and came to a grinding halt. I was transfixed, reading the last half of the aya over and over again.

“And indeed, it is difficult except for the humbly submissive”

What does that mean? What does that say about me? Are my struggles with consistency in prayer a sign of my lack of submission? This journal alone is proof of the never-ending cycle of spiritual disappointment in which I’m caught. Surely, this repetitiveness holds some type of meaning. How do I crawl out of the abyss?

Am I beyond help and hope?

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Here (?)

This has been a surprise - in more ways than one.

2018 has been moving at the speed of light. Sometime in January, someone made the joke that “Ramadan garrab” [Ramadan is almost upon us], and we all laughed at the funny witty thing and then went about our conversation.

Yesterday, I sat at the kitchen table in disbelief as my mother discussed Ramadan preparations with her sister over Skype. How did we get here so soon? Panic set in. Google said Ramadan was to start on Tuesday, while my aunt’s tinny, robotic voice over Skype (connectivity issues are a staple in my family) said that it was between Wednesday and Thursday. As the day went on, my panic gradually melted into resigned acceptance - Ramadan will most likely be on Wednesday, and I better get with the program.

This morning, my aunt called, and after the routine struggle, her voice burst through the iPad: “galu Ramadan yom alkhamees - walai alyom da kunna mu7tajinnu!” [Ramadan is on Thursday, thank goodness because we needed that extra day]

What?? Thursday?? My mind swirled with confusion. But I had prepared myself for Wednesday! I felt disoriented, and disappointed, but that didn’t last long as the plans for kham alramad quickly began to take over my headspace. “Sushi!” was my father’s suggestion, and a good one at that. Yeah, sushi sounds like the right way to binge before we begin fasting. My muscles relaxed. I decided against the coffee I was going to drink - “I have another day”. I went about my day.

Three hours ago, I decided to check Google one more time, “just to be sure”. The Islamic Community Center of Tempe’s website was unceremonious in its announcement, opting to simply paste the Ramadan prayer times on the page.

“Day 1: Wednesday, May 16th - Fajr 4:09am”

UM, EXCUSE ME?

A wave of fear washed over me. Then I looked at the top of the page, where a clock was counting down - 17 hours until Ramadan.

I should have just minded my business.

I frantically clicked back to the Google search page to find some other, more reliable source (sorry, ICC Tempe). ISNA! They’ll know! But the bold yet dull font on the ISNA page only confirmed what I had read before. For some inexplicable reason, America has decided to fast a day earlier than everyone else.

The emotional whiplash has left me completely unprepared - for fasting, and for this edition of Ramadan Notes. Sure, I could have been like any other self respecting Muslim (especially one documenting their journey through the Ramadans) and not waited til the last moment to ready myself, but like... leave me alone.

So thus begins another round of fasting and introspection while worship. The last few years, I’ve opted for a loose theme. This time, for (the) obvious reason(s), I’m winging it.

So here goes... something. Ramadan Kareem everyone! :)

(PS: If you’re a new reader, are fasting on Thursday and/or are generally underwhelmed by this post, feel free to check out the entries from the last few years of Ramadan Notes. They’re much better put together - for the most part.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Fasting and Periods

It’s that excruciating time of the month. No, Ramadan hasn’t gotten so difficult that I’ve just decided to give up. I’m on my period. (great timing, uterus)

Those words are surprisingly difficult to write so overtly. Because for all my boldness, progressiveness and “liberation”, I still struggle to talk about this - thing - in mixed company, particularly during Ramadan. It’s so juvenile to feel that way.

In the Lord’s infinite wisdom, he decreed that women should not fast while on their periods - which makes complete sense, because at the very least, not eating and losing all that blood is a terrible combination. But even though it’s a rule written in the texts, that everyone knows, we all act like it’s a secret. Men act like they don’t know, asking stupid questions like “Did I just see you drink water?! Are you not fasting?!?” Women act like they should be ashamed, like they’re terrible Muslims for not fasting while on their periods, which is what I used to do for a long time. Fast while on my period. Because I was afraid someone (read: any Muslim man in the world) would see me eating or drinking and reprimand me for it, even though it’s none of his business and, more importantly, even though God told me not to.

I think the worst part is that people (read: Muslim men) assume that you’re somehow lucky. Like you’re on vacation. “At least you’re not fasting.” Like fasting is really the most difficult thing my body can go through.

So allow me to make this a wildly uncomfortable read for everyone by telling you, dear reader, about the “break” that is my period:

[note that this experience is *mine* and doesn’t necessarily speak to the experience of all Muslim women across the world. Also note that, while the language used below may seem like it, it is not an exaggeration.]

Almost every month, I go through a death of sorts. I’m not trying to be poetic when I say this, although sure, one could say that like the phoenix, the lining of my uterus is reborn every month. I mean I almost die.

My menstrual cramps are not the ones depicted in Motrin commercials, where the woman hugs her stomach and cutely winces at the camera, and then in the next shot she’s taking a (singular) Motrin pill and then skips off in her white pants to have lunch with her friends. My menstrual cramps are not even limited to my ��menstrual area”. For about 5-7 days (plus two weeks; see below), my menstrual cramps take over my entire body.

It starts with pain attacking all the joints, two weeks before my period has even started. During this time, there’s also the light flirtation with actual menstrual cramps - random stabs of searing pain here and there (usually at night) to remind me of the impending, looming doom. As we get closer to D-Day, these symptoms start to intensify and attack more regularly. By the time Aunt Flo has arrived, I am veritably alight with pain from my stomach all the way down to the soles of my feet. My wrists, knees and ankles, which before just ached, now feel like they’re about to explode. Iron nails (like the ones used to secure train tracks) feel like they’re being hammered into my hips and down through my legs to fasten me to the ground.

When I’m feeling this way, my appetite is obliterated and food is the literal last thing on my mind. But there’s still vomiting, which in my younger years was a 100% certainty. Violent, gut-wrenching vomiting that doesn’t stop once my stomach is empty, and occurs even if my stomach is already empty because my body is trying to kill me. I have spent many a time passed out by the toilet bowl after wishing for the sweet respite of death.

(I have a lovely anecdote from my college days on one such occasion in which I almost passed out in the street trying to get home. Let me know if you’re interested.)

But I prefer the vomiting to the alternative, which is extreme bloating. If I don’t vomit, then you can bet your bottom dollar that I’m bloated larger than a hot air balloon. My abdominal area is so distended that my skin feels like it’s going to rip open like a zipper and show my internal organs. During these times, even the lightest fabric feels like acid is being poured on my belly.

(So you can imagine how being fully clothed would be a problem)

And nothing helps. My current starting dosage of ibuprofen is 600mg, and it doesn’t even cause a dent (or maybe it does, but by then I’ve already lost consciousness, so what’s the point). Last night, after (only) 4 hours of continuous, uninterrupted, excruciating pain and bloating, I started to cry in the middle of the street while waiting for my father to come drive me home. Because even worse than the pain is the frustration at being in so much pain, and not being able to do anything about it.

I won’t get into what it feels like to be going through all this, and still be forced to interact with people in a normal fashion, without letting them know that you’re being murdered by your own body and literal blood is coming out of you, fielding their questions about why you’re drinking water so you won’t embarrass yourself or make them uncomfortable, and (if they’re progressives) smiling politely while they tell you how "lucky” you are that you’re not fasting, I’ll just end with this:

I would rather fast 24 hour days for a full month, than go through one day of this.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sideways

That’s how this blog has gone - sideways.

Every evening since my last post, I’d sit on the couch with my family after breaking fast, and try to convince myself to write. And every evening, I’d eventually peel myself off the couch and go to bed.

I lost my grip on the momentum, slipped through a crack, down a rabbit hole and couldn’t climb back out. Life got in the way. I got tired. I got lazy. And I’m disappointed.

I broke a two-year run, one that I had been particularly proud of. You know this by now, but I have a problem with consistency, and this blog has been proof to myself (and you?) that I can overcome that problem. Until now, that is.

I could say that this Ramadan has found me (willingly) shouldering the responsibility of preparing iftar for my family and their weekly guests, and that’s what’s been keeping me from my daily writing ritual. And that would partly be true. But in reality, I could have pushed myself to write. I should have. But I think ultimately, I was afraid that if I did, whatever i wrote wouldn’t be genuine; that it would be uninspired, a product of obligation and not in the true spirit of this initiative.

So I didn’t. And one day turned into two, three, almost a week.

Yesterday, as I sat on the couch, staring off into space, having the usual internal battle - “get up, go get the laptop and write. Inshallah satrein. Just write.” - my mother looked over from where she was sitting across from me and said, “You know, you’re so lucky.”

“What?”

“You’ve been putting all this effort into feeding everyone - I mean, before I came, you were doing this by yourself. This is a big thing in Ramadan. God has given you a great opportunity to earn 7asanat [good deeds].”

She was right, and it only dawned on me when she mentioned it. Here I was stressing about these daily reflections, which I considered my most personal (meaningful?) form of ibaada [worship], when God had offered me a different (and, lets face it, probably more substantial) way to put in work and live in the Ramadan spirit.

And just like that, disappointment checked out and motivation checked back in. Alhamdulilah.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Personal is Too Personal?

Facebook reminded me that on this day last year, I posted my first Ramadan Note of 2016. I captioned the link with, “Last year, I reflected on a Quran verse a day. This year, it's a lot more general (and personal).” It seems that with each passing year, my reflections become more specific to my own circumstance, and in the process, a lot more revealing of my self.

Last night’s post was the epitome of that. I “bore my soul”, as it were, and shared something I never thought I would so blatantly and honestly discuss [in a public setting]. I haven’t described something about my life in such a raw and unfiltered way in a while, if ever. For a long time, I refused to accept that this is how my brain processed these situations. I downplayed my feelings, or ignored them completely. I was afraid to admit it to myself, let alone to someone else. Writing about it seemed almost exhibitionist.

My family is very private. We are firm believers in keeping things to ourselves, and being very careful of who we choose to share our selves with, even within our unit. This might be characteristic to my family, but it is also most likely a characteristic and product of our culture. For a society that stresses communal living so much, Sudanese people are strangely secretive (usually about the wrong things). This stems from many things, I’m sure, but most prominent of which is the concept we call sutra - the Islamic sitr. Literally meaning “veil”, it is the idea of “drawing a blind over something that should not be revealed”. In layman’s terms, not airing dirty laundry.

Much in the way that sitr and awrah [shame] go together, so do sutra and 3eib [shame]. Of course, what’s 3eib and should be mastoor is incredibly relative, and sometimes clear off the mark (see parenthesized comment above). In 2009, I wrote this piece about exactly that. It took a lot of hard work to get myself to ask those questions and reevaluate my stance, and I’m glad I did it.

While I of course believe that not everything is meant to be shared and some things should and need to remain private, I think I (now) draw my line at a different spot than others - and certainly my family. Some things should be shared because they shine a much needed light, not just in our dark corners, but in others’ as well. Some things should be shared because they serve a greater purpose. And some things should be shared because, well, they’re not 3eib at all, and we’re carrying their weight for nothing.

When I share things, particularly in writing, it is an out of body experience. It’s as if I’m speaking about someone else. The act of writing it down frees me, it removes any sense of intimidation or shame that I may feel (in that moment), and allows me to be open and honest. Of course, this doesn’t apply to everything, and doesn’t permanently get rid of the feelings of intimidation and shame - they are bound to return, whether on their own, or prompted by commentary.

But nonetheless, I appreciate the chance to feel liberated, even if just for a moment.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On (Social) Anxiety

If you’ve been following this blog for more than the last ten days, then you’ve probably come across me talking about this topic before.

I don’t do well around strangers. Well, it’s a bit more than that; I’m incredibly uncomfortable around people I don’t know. More still, I have intense anxiety (in general, but for the purposes of this post) when around people, and particularly in groups. This, as you can guess, affects my life in many ways. It keeps me from socializing and striking new friendships, makes me both physically and behaviorally awkward in public, and even hinders my professional development.

So, you can imagine how Ramadan - a time for people to get together, often in large groups, to break bread, socialize and worship - might be difficult for someone like me. I avoid breaking fast at other people’s houses. I tell my parents/friends that it’s because I don’t like going out during Ramadan, that I am used to the routine we’ve built at home. And that’s true, to some extent. But what I don’t mention is that I don’t want to go because I won’t know how to carry myself - literally. My body is heavy, clunky, foreign to me when in other people’s homes. I am hyper aware of my movements: I’m tapping my spoon too loudly against the bowl; I’m getting bread crumbs all over the table; I don’t want to sit at the table with all those people, but I’m scared to balance the plate on my knees, it’s going to fall and break and I’m going to get food everywhere and everyone is going to look at me. I don’t want them to look at me.

My social anxiety is highest during group prayer. Whether at someone’s home or in a mosque, it is an experience that I dread and try to avoid as much as possible, because the whirlwind of thoughts and feelings I go through before and during are agonizing and overpowering, nullifying any prayer I might attempt to perform. I spend the time obsessing over my wudu, my posture, my scarf, my clothes, the position of my hands, convinced that the women to my left and right are judging me, convinced that I’m doing it wrong. In those moments, the pain is physical.

If I can’t avoid being in a social situation, then I spend time beforehand preparing myself mentally and emotionally. Besides the “pregame pep talk”, this also involves keeping myself busy during the function (you can find me in the kitchen or other labor-intensive area). The prep time helps me to be a functional human being for as long as possible - which, from experience so far, is about two and a half hours.

That is *not*, however, what happened yesterday (also known as the day I just wrote a title and called it a night). I knew my brother had invited his neighbors for iftar, but I didn’t know what time they were arriving and hadn’t taken the necessary precautions. So when I came out of my bedroom and walked into the kitchen to find the neighbor lady talking to my sister-in-law in the kitchen, I panicked - in the literal sense of the term. I froze, then backed out of the kitchen, spinning around to run back into the bedroom, only to be met face to face with the neighbor’s husband. I stuck my hand out at him, but I couldn’t tell you what I said to him, or what he said to me. I couldn’t hear anything but the blood rushing in my ears. Cornered by him, I had no choice but to go back to the kitchen (to appear normal) and say hello to his wife.

After that, I lost control. I could feel my insides vibrating; my mind was in overdrive. I heard my brother tell them about gongoleis [baobab fruit] as I turned on the blender to make the juice. I ended up spilling the entirety of the blender’s contents all over myself and the kitchen counter. I panicked at wasting the juice, I panicked at making a mess, I panicked at facing the guests who were told about and were now looking forward to the juice I had just spilled.

I spent the remainder of the evening in almost complete silence. I couldn’t make eye contact with anyone - not the guests, who were kind enough to look at me and (try to) include me in conversation, not my brother or his wife. I wanted to leave the table and go to my room, but I didn’t want to (further) embarrass my family. So I kept my head down, staring at my lap, fighting the blunder replay happening in my head, distracted and then embarrassed by the two crumbs on my legs, suddenly aware and disgusted by the thickness of my thighs pressed against the seat. I wondered if anyone else saw, and just in case they did, I lifted my legs up from the chair, balancing on my toes to minimize their size.

Eventually, they left, and I, drained and distraught, headed to my room and tried not to fall apart.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Maybe Later

We had people over tonight.

Friends of my brother. It was an interesting experience. I want to tell you all about it. I want to tell you about how we introduced them to Ramadan, to Islam, to Sudanese culture and food. I want to tell you about how it felt to help my brother share this part of his life and self with his friends. I want to tell you about what Ramadan does to my social anxiety.

But I’m exhausted. I’m struggling to keep my eyes open. The sentences in my head have evaporated to form word clouds, and the ideas are becoming less tangible with every tap of the keyboard.

I want to tell you all about it, but not now.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who Are You Doing This For?

It’s easier when there are other people around.

"Alduhur azzan”. They get up to pray, and so do you. Not because you want or need to, but because that’s just what you do - that’s what everybody does. It’s less about the act, and more about the communal action. So you follow. You stand in line, your body firmly on the mat, your mind totally elsewhere.

You do it because you’re scared of what they would say and how they would see you. You don’t want to disappoint your parents. You don’t want to be branded and rejected by your community. You’ve seen people written off for much less, and you know the destructive power of ‘reputation’. You know that the damage will radiate to affect more than just you.

Or maybe you do it to spare yourself the discussion. You don’t want to have to explain why you’re not getting up to pray. You don’t want to be subjected to their unsolicited advice - or worse, their chastisement. Because maybe tough love and nagging don’t work for you; they make you even more stubborn, hardheaded, less inclined to comply.

Maybe you’re like me, and you don’t want to be a hypocrite. You don’t want to put your hands to your heart and recite a prayer meant more to placate the people around you than to please your maker. So when they get up to pray, you make yourself scarce. You pretend to be busy. You head off with purpose to a bathroom, or a bedroom, where you wait until it’s safe to come back out.

Maybe you just want to be alone, to have room to think, to look inside yourself and find out what you truly believe. You want to do your own spiritual ijtihaad to find the interpretation that makes the most sense to you. You’re tired of following blindly, and want to discover your faith for yourself without the pressure of watchful eyes and judgmental mouths.

Or maybe you don’t, because you’re afraid that if you’re alone, you’ll realize that you’re not as secure in your faith as you thought. That staying committed is hard work. That all this time, it was just easier because there were other people around.

5 notes

·

View notes