Straeon Cwiar Cymru - Queer Welsh Histories https://linktr.ee/queerwelshstories

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Terrence ‘Terry’ Higgins was born on the 10th of June, 1945, in Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, Wales, where he left as a teenager because of his sexuality. He worked in London as a reporter in the House of Commons, a nightclub barman and travelled to Amsterdam and the USA as a DJ. He was working when he collapsed at the Heaven nightclub in London.

Terry died on the 4th of July, 1982. He was one of the first people in the UK to die of an Aids-related illness, at the age of 37. The 10th of June, 2019, would have been his 74th birthday.

The Terry Higgins Trust was started in 1982 by Terry’s partner Rupert Whitaker, and Terry’s friends Martyn Butler, Tony Calvert, Lee Robinson and Chris Peel. In 1983 it formally became the Terrence Higgins Trust, ‘the first charity in the UK to be set up in response to the HIV epidemic.’ It remains the leading HIV and Aids charity in the UK and the larget in Europe.

The Terrence Higgins Trust: Website and Twitter.

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Balchder hapus! Happy Pride!

Ar ddiwrnod diwethaf mis Balchder, dyma gyfieithiad Cymraeg o erthygl ysgrifennais ar gyfer Art UK, ar fenywod cwiar Cymreig yn y celfyddydau.

On the last day of Pride, here's an article I wrote for Art UK on Welsh Queer Women in the arts (it is also in English).

#art uk#lgbtqia#wales#welsh#cymraeg#cymru#lgbt history#lgbtqia history#sapphic history#lesbian history#trans history#history#etc.

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On the 29th of June, 1985, LGSM and Welsh miners striking in the 1984-5 national Miner’s Strike led London’s Lesbian & Gay Pride parade. They marched with the ‘Lesbians & Gays Support the Miners’ and miners’ banners, such as the ‘Blaenant Lodge’ banner. As the largest group to march, they were asked on the day to lead - on the 30th anniversary in 2015, it was Barclays Bank who led the Pride in London parade.

Photographs via LGSM and Colin Clews.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

'Queer Welsh Women in Art' - including Ladies of Llangollen, Cranogwen, Gwen John, Nina Hamnett, Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, Jan Morris and me!

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

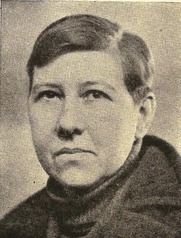

The Queer Life of Cranogwen

‘Cranogwen’ (9 January 1839 - 27 June 1916), or Sarah Jane Rees, was born in Llangrannog, the daughter of Frances Rees and mariner John Rees. Unusually for the time, Cranogwen was educated at the local school along with her brothers, until the age of fifteen. Often regarded as most unusual about Cranogwen’s life is her experience as a sailor, having then joined her father on the sea, trading along the coast and sometimes to the mainland of Europe. It was however not uncommon for girls and women to accompany male members of their family to work. Sailors’ wives and children did accompany them, though this was disallowed on Royal Navy ships in 1869. Some other female sailors who could now be regarded as queer, and some sailors now could be regarded as trans men. Cranogwen, however, returned to education after three years on the sea, to navigation schools in New Quay and London, and in 1859 set up her own in Llangrannog. Though there is evidence of criticism towards women running navigation schools, from churches and the ‘Blue Books,’ there is no record of such criticism towards Cranogwen.

In 1865 Cranogwen won in the National Eisteddfod at Aberystwyth with ‘Y Fodrwy Briodasol’ (The Wedding Ring), which expresses criticism of the expectation on women to marry through the viewpoints of four brides, including one suffering domestic abuse. She beat famous male poets such as Islwyn. Her bardic name was made up of the names of Saint Caranog, who Llangrannog was named for, and the nearby river Hawen. With continued success at Eisteddfodau, Caniadau Cranogwen was published in 1870 and Cranogwen spoke across Wales, and toured as a Methodist lay preacher, including two American tours.

In 1874, Fanny Rees, from Llangrannog, contracted tuberculosis and moved into Cranogwen’s family home to die her arms. Cranogwen’s grief at the tragic end of her first same-sex relationship is described in autobiographical writings, as are her poetry to women thought of as her most passionate writing, such as ‘Fy Ffrynd’ (’My Friend’). (There is also a passionate poem to her, by Buddug, which describes how she nearly worships and admires the ‘immortal’ Cranogwen.) As Cranogwen continued to live with her parents, Jane Thomas lived next door, as her supportive and committed partner. When Cranogwen’s parents died, she sold the house and lived with Jane for the last twenty years of her life.

From 1878, Cranogwen was editor of Y Frythones - not the first magazine for Welsh women but the first edited by a woman - which had more proto-feminist and even queer messages than its predecessor, though still contained lessons on being a respectably middle class and religious woman. But within these lessons, Cranogwen promoted Welsh women’s writing, ensuring Y Frythones was written for women by women, told her readers they did not all need to marry, like ‘the woman here by our side’ (Jane Thomas) and would give answers, in the ‘Questions and Answers’ column, that can now be analysed as queer. In 1887, when a reader wrote in questioning short bob hairstyles on women, saying she could not tell whether those with these hairstyles were girls or boys, Cranogwen answered: “First of all, then, ask that person which he or she will be, a boy or a girl? Then proceed with your business.” When readers asked about women becoming preachers, like Cranogwen herself was, she concluded that, “Gender difference is nothing in the world.”

Cranogwen was a sailor, teacher, poet, writer, editor, temperence activist and much more. Her legacy is a feminist legacy - ‘Llety Cranogwen’, a shelter for homeless women and girls was founded in the Rhondda by the South Wales Temperance Union and Cranogwen was one of the women who contributed to Welsh women’s writing and education. She continues to be an inspiration, to the Welsh group ‘Cywion Cranogwen’ and to modern Welsh magazines by and for Welsh women, such as ‘Codi Pais.’ Her legacy is also a queer legacy, inspiring queer women and people, and Cranogwen was open about her relationships in her own lifetime (though as 'romantic friendships), which are now too often erased in the teachings about this ‘immortal’ woman. Fanny Rees and Jane Thomas, who loved and supported Cranogwen, and the queer themes in poetry by and to Cranogwen, should now be permanently included in her history. Their histories should not be erased and neither should the significance of Cranogwen’s legacy to LGBT+ people, and especially queer women.

Sources & further reading: - Cranogwen, Caniadau Cranogwen, & Cranogwen ed Y Frythones. - Jane Aaron, ‘Gender Difference is Nothing,’ Queer Wales, ed Huw Osborne & ‘Developing Women’s Welsh-language Print Culture’ Nineteenth Century Women’s Writing in Wales. - Katie Gramich & Catherine Brennan ed Welsh Women’s Poetry, 1460-2001: An Anthology. - Norena Shopland, Forbidden Lives: LGBT Stories of Wales. - Sian Rhiannon Williams, ‘Y Frythones: Portread Cyfnodolion Merched y Bedwared Ganrif ar Bymtheg o Gymraeg yr Oes,’ Llafur, IV, 1 (1984).

Photo via National Library of Wales | Llun o Lyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru.

146 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Gwen John was born Gwendolen Mary John on the 22nd of June, 1876, one of four children of Edwin William John and Augusta John (née Smith). Gwen was 8 years old when Augusta passed away, when her family then moved from Haverfordwest to Tenby, where they would often sketch the Pembrokeshire coast.

Her earliest surviving works are from when she was 19, when she began to study at the only art school in the UK that would take female students, Slade School of Art. She developed a relationship with artist Ambrose McEvoy (a portrait by him of Gwen survives), but she also had a relationship with another woman at Slade - her identity is unknown but the relationship was known to Gwen’s brother to be so intense that the woman’s ‘love’ for Gwen ‘turned to hate’.

Gwen won the Melville Nettleship Prize for Figure Composition at Slade, and first visited Paris in 1898, studying under Whistler. She exhibited in London when she returned in 1899, living very poorly, before returning to France in 1903. Gwen was an artist’s model in Paris in 1904, including for Rodin, who she developed a relationship with - she was devoted to him for the next decade.

Despite the famous European artists Gwen met, she preferred to work in solitude. She could afford to work independently and no longer work as a model when patroned by John Quinn from 1911. She continued to exhibit but could be too perfectionist to complete some works. After the end of her relationship with Rodin, Gwen became increasingly Catholic.

Of course, she also lived in solitude, except for her cats. She possibly remained living in France to avoid personal relationships, like with her family. However, she still developed feelings and relationships in France that could be intense and sometimes one-sided.

It is certainly known that Gwen was attracted to men and women, and was likely bisexual. Rodin drew Gwen erotically with Hilda Flodin, his assistant who he also had a sexual relationship with, but Gwen’s own main subjects in her work are women (and cats). Certainly it’s possible to see Gwen’s interest in women in her paintings of various women, whether or not she had relationships with those women.

As well as the women already mentioned, Gwen also was infatuated with another unnamed woman, a married woman in France, and German artist Ida Gerhardi herself was infatuated with Gwen. This was unrequited, as was Gwen’s most intense infatuation with Véra Oumançoff. Gwen wrote 2000 letters to Rodin, especially when she could not get his undivided attention in person, telling him of different aspects of her day and her life. He died in 1917 and it was in 1926 she developed an attachment to Véra, who she also wrote letters to, some (but not many) of which survive at the National Library of Wales. Though these aren’t many, in one of them, Véra asks Gwen whether she needs to write to her every day.

“I don’t think so,” Véra wrote, in French, “- and I even think that it is bad for your soul - for you are too attached to a creature, without ever knowning it, so to speak. I am well aware that you have great sensitivity, but you must direct it towards Our Lord, towards the Blessed Virgin.”

Gwen also sent Véra about 100 drawings, which were discovered in a cupboard after Véra’s death in 1959. This one-sided relationship ended in 1930 as Véra’s family wanted to concentrate on prayer.

By 1933, Gwen had stopped painting, and lived the end of her life in isolation, leaving to Dieppe in 1939, with a will and burial instruction, and dying in a public hospital there on the 18th of September.

The grave was unknown until it was found that Gwen had been buried as ‘Mary John’ in a Dieppe Cemetary, in the 2015 S4C documentary Mamwlad, presented by Ffion Hague. A memorial plaque was added in Dieppe in 2015, finally marking the rest place and celebrating one of the most famous artists from Wales - or perhaps even the most famous artist from Wales, and not just the most famous female artists from Wales either. (Though of course how Welsh her identity was can be also debated.) As she is herself more recognised, rather than just her associations with men, her bisexuality also is increasingly recognised, and perhaps Gwen John is also better understood.

The plaque is inscribed with a quote from a letter of Gwen’s:

Mae pobl fel cysgodion i mi ac fel cysgod ydwyf innau.

(People are like shadows to me and like a shadow I am to them.)

Sources & Further Reading:

Gwen John Self-Portrait.

Gwen John sources at National Library of Wales.

Ceridwen Morgan-Lloyd, Gwen John: Letters and Notebooks

National @museumwales blog ‘LGBT Figures from Welsh History.’

Norena Shopland, Forbidden Lives: LGBT Stories from Wales, 2017.

155 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kathleen Freeman was born on the 22nd of June, 1897, in Yardley, Birmingham. By 1911, she and her parents, Charles H Freeman, a commercial traveller, and Catherine Freeman (née Mawdesley) had moved to Conway Road, Cardiff. Kathleen attended Canton High School and University of South Wales and Monmouthshire (Cardiff University).

After graduating with a BA in Classics, Kathleen stayed on at the University as a Greek lecturer, being awarded an MA and D.Litt. During the Second World War, she lectured for the Ministry of Information and HM Forces in South Wales. In 1946, having become a senior lecturer, she resigned from Cardiff University to focus on her writing and research.

As well as publishing academic texts on Classics and Greek translations, Kathleen was a mystery and detective writer. She was admitted into the Detection Club in 1951, a group of mystery writes which included Agatha Christie. Mary Fitt was her most used and well-known pseudonym, under which she published 27 novels and short stories from 1936, but she also wrote as Stuart Mary Wick, Clare St Donat, Caroline Cory and ‘T’other Jane Austen.’

From the 1930s until her death on the 21st of February 1959, Kathleen lived with her partner Dr Liliane Clopet, a GP and writer, at Lark Ride, Druidstone Road, St. Mellons (outside Cardiff). Several of her books were dedicated to Liliane. Liliane died in Newport in 1987, aged 86.

Sources:

‘FREEMAN, KATHLEEN (‘Mary Fitt’; 1897 - 1959), classical scholar and writer,’ The Welsh Biography

‘Inspirational People: 3. Kathleen Freeman – Classicist and Fiction Writer,’ Judith Dray, Cardiff University Blogs

‘How to Conceal a Female Scholar; or, the Invisible Classicist of Cardiff,’ Edith Hall, The Edithorial

Kathleen Freeman, A Brief Biography & Bibliography, M. Eleanor Irwin, University of Toronto

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

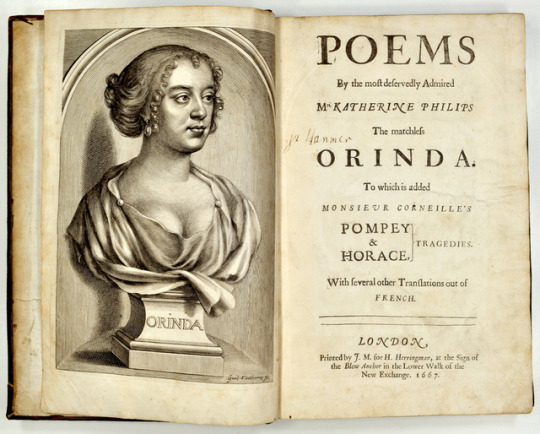

Katherine Philips was known as the “Matchless Orinda,” or sometimes, the “Welsh Sappho”. Born Katherine Fowler in London in 1632 to a wealthy family, she was an intelligent child - could read and write from a young age, learned the Bible and several languages, and was even sent to school.

One of Katherine’s closest friends at school was Mary Aubrey, who would become ‘Rosania’ in Katherine’s poetry - some of the earliest romantic friendship poetry known of in Britain. This was perhaps when Katherine began her ‘Society of Friendship.’

Katherine’s father died when she was 10 years old and when her mother remarried, they moved to Wales. Katherine herself got married at about 17 years of age, to a distant cousin James Philipps, who was certainly older, though there is debate around his age, which may have been mid-20s, or mid-50s. This was shortly afted Katherine penned the poem “A Marry’d State,” which was certainly critical of marriage.

She then moved to Cardigan Priory, which became central to her ‘Society of Friendship,’ where she, ‘Orinda,’ wrote poetry to other women, and was herself admired by women in poetry, as the ‘Matchless Orinda’. As Katherine lived between London and Wales, perhaps rural life in Wales more isolated and lonely, she expanded her Society of Friendship, taking on new members such as Anne Owen from Pembrokeshire, who was known in Katherine’s poetry as “Lucasia”.

Katherine’s relationship with Mary Aubrey ended bitterly when she didn’t invite Katherine to her wedding, perhaps because of Katherine’s intense poetry (it’s difficult to know what Mary’s reaction would have been as her responses don’t survive), Katherine wrote ‘On Rosania’s Apostacy, and Lucasia’s Friendship.’ This made clear her feelings for Lucasia, as did ‘To My Excellent Lucasia on our Friendship’ and ‘To my Lucasia, in Defence of Declared Friendship.’ This relationship ended when Anne Owen remarried in 1663. Before her death, Katherine also wrote poetry to ‘Berenice,’ whose identity is unknown.

Katherine’s sexuality and the nature of her poetry has been debated, but it is clear that Katherine shared romantic relationships with women, and had strong feelings for them, which survive in her poetry. She herself mentioned Sappho in her poems and was compared to Sappho after her death.

Katherine died of smallpox on the 22nd of June, 1664, only 32 years old, in Rosania’s arms in London. Katherine was survived by 1 daughter, who she’d named Katherine, and also had 1 son with James, Hector, who had not survived. Though her poetry was published posthumously, Katherine became obscured, but has been appreciated again since the 20th century, as one of the first British female poets to be celebrated in her own lifetime, as well as one of the first British poets to write romantic friendship poems.

Katherine Philips can certainly be appreciated as an acclaimed Anglo-Welsh poet who was highly influential in her writing of female same-sex love. Katherine’s poetry certainly mostly focussed on women and, as her Society of Friendship was influential to women in her lifetime, at least 2 of which she had passionate relationships with, Katherine continued to be an inspiration to other woman poets after her death.

Sources & Further Reading:

Katherine Philips Manuscript c. 1655 on People’s Collection Wales.

Katherine Philips, National Library of Wales.

Katherine Philips poems held by the British Library.

Some more biography on Poetry Foundation.

Norena Shopland, Forbidden Lives: LGBT Stories from Wales, 2017.

See more sources from Oxford DNB.

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

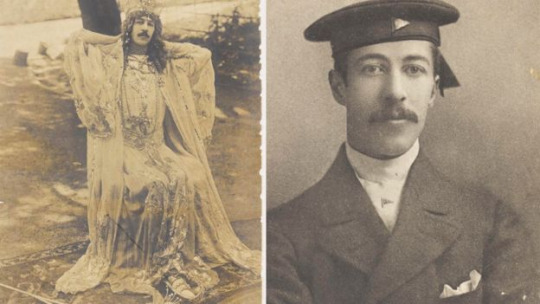

Portrait of John Gibson by Penry Williams, 1845 (via Tate) & John Gibson by Charles Edward Wagstaff, after Penry Williams, 1845 (via NPG).

John Gibson was a sculptor and Penry Williams an artist. Both were from Wales and both settled in Rome in the early 19th century and became famous there. It is believed they had a relationship in Rome, until Gibson’s death in 1866.

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

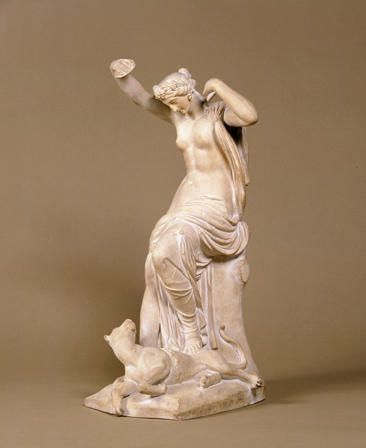

Sculptures by John Gibson at the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff; ‘The Wounded Amazon,’ ‘A Bacchante diverting the Attention of a Tiger,’ ‘Aurora,’ and ‘Nymph and Cupid.’ @museumwales

John Gibson was born on the 19th of June, 1790 in Conwy and died in Rome on the 27th of January, 1866. Welsh lesbian sculptor Mary Charlotte Lloyd and the American lesbian sculptor, Harriet Hosmer both studied at Gibson’s studio in Via della Fontanella, which was also a tourist spot for a number of other lesbian and feminist women.

John Gibson is thought to have had a relationship in Rome, until his death, with the Welsh artist Penry Williams.

77 notes

·

View notes

Photo

John Menlove Edwards was born on the 18th of June, 1910 at Crossens near Southport, Lancashire. The son of a ‘radical’ socialist vicar, he was educated at boarding school and Liverpool University, to become a psychologist, and was a conscientious objector during the Second World War. He became a child psychologist at Great Ormond Street and Tavistock Institute.

John Menlove is most remembered for his rock climbing, particularly his ‘pioneering’ climbs in Snowdonia (Yr Wyddfa). He wrote about his climbing and was written about - he authored books on Cwm Idwal, Tryfan and Lliwedd.

He has also been written about as ‘homosexual,’ perhaps openly so, having had a relationship with another climber, Wilfrid Noyce, whose life he saved in 1937 and who went on to climb Everest, in the first exhibition in 1953 (which was reported on by none other than Jan Morris).

However, John Menlove suffered from mental illness, particularly paranoia, and was sectioned at North Wales Hospital in Denbigh (a psychiatric hospital), where he was given electroconvulsive therapy. He died after taking a cyanide pill on the 2nd of February 1958, aged 47. His sister Nowell Mary and her husband Hewlett Johnson scattered his ashes on a Welsh hillside near Hafod Owen.

Sources & Further Reading:

“Edwards, John Menlove (1910-1958), rock climber,” Ioan Bowen Rees, Dictionary of Welsh Biography

“A Black Rainbow: The Life and Times of Menlove Edwards”

“Paying homage to an openly gay talented rock climber of the 1930’s,” Pride Exhibitions

Life of John Menlove Edwards by Jim Perrin

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Victor Spinetti was born Vittorio Giorgio Andre Spinetti on the 2nd of September, 1929 in the coal-mining village of Cwm, in the historic county of Monmouth, to Welsh parents, and of Italian descent.

Victor was educated in Monmouth School and the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama. His acting career spanned from the late 1950s to early 2000s, during which he appeared in 30 films, including the first three Beatles’ films, ‘A Hard Day’s Night,’ ‘Help!’ and ‘A Magical Mystery Tour, as well as ‘The Krays,’ ‘Return of the Pink Panther’ and ‘Under Milk Wood.’

His acting on theatre won him a Tony for his role in ‘Oh! What a Lovely War’ and he also directed theatre productions such as ‘The Biography Girl,’ ‘Jesus Christ Superstar’ and ‘Hair.’

Victor was also an author and a poet, having written a memoir, poetry and prose in various publications.

In college, Victor met Graham Curnow, an actor from Pontypridd who appeared in ‘Horrors of the Black Museum,’ who also was gay. They were partner for 44 years, until Graham’s death in 1997. In 2006, Victor said of Graham, who he’d lived with in Brighton, “He was home to me.”

Victor went on: "We were together for 44 years, but we never showed any emotion when we were in public - it wasn’t the done thing and we would have been classed as criminals for loving each other.

"Even when he was ill and I was watching him dying, I wanted to reach out and touch his hand. But I think he would have pulled it away. You had to be careful about expressing this love, the love that ‘dare not speak its name’.

"And that is why, today, my heart sings for young men holding hands.

He was my life’s companion.”

Victor died on the 18th of June, 2012, in Monmouth, aged 82.

93 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In 1841, Welsh landlowner and Conservative MP Stephen Glynn, 9th Baronet, sued ‘The Chester Chronicle’ for allegations of homosexuality during his election campaigns, who were forced to apologise.

Born on the 22nd of September 1807, he inherited the baronetcy from his father aged 7, which included Hawarden Castle. He was MP for the Flint Boroughs from 1832 then for Flintshire from 1837 to 1847. He was also an antiquary and studied Church architecture. He died on the 17th of June, 1874, unmarried and childless, so the baronetcy died with him.

Image via ‘Welsh Pride - A Timeline of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, & Transgender (LGBTQ+) History In Wales’ by Norena Shopland - download here.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Updated! Wedi'i ddiweddaru!

🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏴 2025 Prides in Wales - Digwyddiadau Balchder 2025 🏳️⚧️🏳️🌈🏴 Again, so many Prides happening in Wales this year! Here's a list of them, with more details to be added and updated once they're revealed by the Pride! Sut gymaint o Balchder yng Nghymru eto! Dyma rhestr - wnai adio mwy pan bydd mwy o fanylion yn cael eu datgelu! May - Mai 11 - Colwyn Bay Pride Bae Colwyn @togetherforcolwynbay 17 - Balchder Machynlleth Pride @balchder_mach_pride (with other events in the week before) 17 - Swansea Pride Abertawe @swanseapride 18 - Swansea Family Pride / Abertawe Pride Teuluol at the National Waterfront Museum @museumwales 24 - Blaenau Gwent’s 1st Pride! From 12:30pm at @bedwelltyhouse @blaenaugwentcouncil June - Mehefin 7 - Bridgend Pride @bridgend.pride 7 - Llanelli LQC Mardi Gras @llanelliqueercollective 7 - Monmouth Pride Trefynwy @monmouth.pride.trefynwy 7 - Porthcawl Pride Party @ The Beachcomber Porthcawl (on Facebook) 7 - Prestatyn's first Pride! 7 - Torfaen Pride (on Facebook) 14 - Barry Pride Y Barri @barry.pride 14 - Pontardawe Pride (on Facebook) 21 - The Big Queer Picnic Cardiff @thebigqueerpicnic 21 - Pride Cymru Cardiff @lgbtpridecymru 28 - Abergavenny Pride Y Fenni @abergavennypride 28-29 - Towyn Pride Weekend @knightlysbar 29 - Cowbridge Pride Y Bont-faen @cowbridgepride July - Gorffennaf 5 - Pembrokeshire Pride Sir Benfro, Dewsley Farm @pembspride 5 - Caerffili Pride @pridecaerffili 5 - Caldicot Pride / Balchder Cil-y-coed @caldicotpride 5 - North Wales Pride Balchder Gogledd Cymru, Bethesda @northwalespride 19 - Flint Pride 26 - Brecon Pride Balchder Aberhonddu @breconpride 26 - Wrexham Pride Balchder Wrecsam @pridewrecsam 28-29 - Llansteffan's first Pride! August - Awst 2 - Llandovery Pride @heartofwaleslgbtq 9 - NPT Pride (NPT Pride 2025 on Facebook) @nptpride 17 - Glitter Pride @glittercymru 22-24 - Trans Pride Cardiff @cardifftranspride 30 - Carmarthen Pride / Balchder Caerfyrddin @carmarthenpride

September 6th - Newport Pride in the Port @prideintheport.newport + Pride in Aberystwyth @prideinaber will return on the 25th of April 2026 Anything left out? Let me know in the comments or in a DM please! Diolch! 🌈

Full post (with images) on Instragram

56 notes

·

View notes

Link

Henry Cyril Paget was born on this day, 16th June 1875.

You may have seen that a film about Henry Paget is being made called 'Madfabulous' and starring Callum Scott Howells and directed by Celyn Jones.

“The Anglesey Tiara was at one time owned by Henry Cyril Paget - fifth Marquess of Anglesey.

It is expected to fetch a six-figure sum at the event in the Netherlands.

But behind the jewel-encrusted treasure lies a story of squandered wealth, Edwardian scandal, and an accusation of “erasing Welsh queer history”. “

Shorter article in Welsh.

#I thought I had a proper blog on#henry cyril paget#I'll need to write one#making a note of it#reserving judgement on the film until I see it#a lot of famous faces in it so we'll see!

249 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Margaret Haig Thomas, known as Lady Rhondda or 2nd Viscountess Rhondda, was born on the 12th of June, 1883, and died on the 20th of July, 1958.

Born in London as Margaret Haig Thomas, her father was politician David Alfred Thomas, the first Viscount Rhondda, and her mother was Sybil Thomas, a suffragette, who prayed that her daughter would become a feminist.

Margaret was raised at Llanwern House, near Newport, until she went to boarding school, and then Oxford, and she was an only child. She became a debutante, and worked for her father at Consolidated Cambrian in Cardiff.

In 1908, she joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), becoming their Newport secretary, and married Newport landowner Humphrey Mackworth, becoming Margaret Haig Mackworth.

Margaret campaigned for suffrage across South Wales and in July 1913, attempted to destroy a Royal Mail postbox with a chemical bomb. After refusing to pay a £10 fine, she was sentence to one month in jail, in Usk. She went on hunger strike and was released after 5 days, receiving a Hunger Strike Medal.

On the 7th of May, 1915, travelling with her father and depressed over tensions in her marriage, she was on the RMS Lusitania when it was torpedoed. Though she suffered from hypothermia, she was rescued by an Irish trawler and recovered at home with her parents for months.

On the 3rd of July, 1918, Margaret’s father died and she became Viscountess Rhondda. She tried to take his seat in the House of Lords but was rejected. She also inherited his title as chair of his company, and was director of 33 companies in her lifetime, 28 of which she inherited from her father.

In 1920, Margaret founded ‘Time and Tide’ a left-wing feminist magazine, a mouthpiece for the Six Point Group, also set up by Margaret, to focus on equality and rights of children.

She divorced her husband in 1923 and lived with the first editor of ‘Time and Tide,’ Helen Archdale, and then had a relationship with author Winifred Holtby (who was in a relationship with Vera Brittain). Her partner of 25 years however was Theodora Bosanquet.

After her death in 1958, women soon were allowed to enter the House of Lords, and Time and Tide continued to run until 1979.

Margaret is pictured and named as ‘Margaret Haig Viscountess Rhondda (1883-1958)’ on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in London. There is also a campaign for a statue of Lady Rhondda in Newport.

Further reading: Angela V. John, Turning the Tide: The Life of Lady Rhondda, Cardigan, Parthian Press, 2014.

67 notes

·

View notes