my name's annie and i write about the movies i like sometimes

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

“King Kong vs. Godzilla” (1962) vs. “Godzilla vs. Kong” (2021)

One of the top reviews on Letterboxd for the new Godzilla vs. Kong (2021) movie reads “I think this movie is good but also I saw it in Imax after not setting foot in a movie theater since March 2020 so honestly ANYTHING would have made me indescribably happy.” Peter: I’m glad you had a good time. Unfortunately, I also saw Godzilla vs. Kong in IMAX after not setting foot in a theater for a year, and the film did not make me indescribably happy. In fact, it did the opposite. What could’ve possibly gone wrong?

For one thing, I was upset that my friend made the decision for me to see the movie in IMAX instead of the regular theater - the screen didn’t look any better to me, and the seats were less comfortable. What did I pay six dollars extra for? The extra loud sound? Petty complaints aside, I had just seen the 1962 version of the film which I had a lot more fun watching. Tastes differ; here is why I liked the original more.

King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962) was directed by Ishirō Honda who also directed the original Godzilla film in 1954. Honda’s version of the battle between these two monsters recognizes that what the viewers want to see is a fight, but also jumps on the opportunity to make a mockery of its human characters. The framing of the fight between King Kong and Godzilla is an ad campaign by a pharmaceutical company, who found some berries on the island where King Kong lives that have a “non-habit forming narcotic effect.” Discovering King Kong, and dissatisfied with his current television ratings, the head of the pharmaceutical company kidnaps Kong from his island and brings him back to the mainland. Coincidentally, American submarines have just accidentally unleashed Godzilla from an iceberg, and he’s also headed for the mainland!

Indisputably, King Kong and Godzilla are natural enemies, although no one really understands why. One commentator gives “the best explanation” for this, saying, “It appears that King Kong … is determined to destroy Godzilla. Thus: a battle of the giants which may or may not have taken place millions of years ago, may be recreated soon.” The human characters in this movie are dull, greedy businessmen who basically just take up runtime until we get to see the monsters. This is a classic formula for kaiju movies (taken to its mind-numbing extreme in Hideaki Anno’s 2016 Shin Godzilla): the audience isn’t really meant to care about the human characters, and, if anything, the monsters are there to reveal something unlikable within humanity.

The best part of King Kong vs. Godzilla is, unsurprisingly, the fights. Yes - it is just two men in suits, and the use of miniatures is obvious, but, for me, there is undeniable charm in those aspects of old monster movies. The focus cannot be on the special effects so the filmmakers have to make these scenes entertaining in other ways. Cuts to the television producers with binoculars - shamelessly enjoying the interactions between Kong and Zilla, trying to predict the outcome and rooting for their favorite fighter - inform (and mirror) the audience’s reactions. This isn’t scary stuff; it’s fun! King Kong beats his chest and Godzilla does some weird stuff with his arms in intimidation: it’s cheesy, but it successfully builds tension.

Fast-forward to 2021: King Kong and Godzilla are no longer played by men in suits, they are computer generated. We can see every individual hair on King Kong’s body blowing in the wind. We’re not afraid to zoom in really close on these monsters. We have the technology to make them look really cool, and they sound cool, too. Shouldn’t that be enough to make the fights cool? It’s been nearly sixty years since the original King Kong vs. Godzilla movie came out, and you can tell. But does all this new technology necessarily make for a better movie? I’m not so sure.

All of my criticisms of this movie are inherently personal, but one of my biggest ones comes down to unabashed preference: I love Godzilla. I think Godzilla is really awesome. To my disappointment, the new Godzilla vs. Kong doesn’t seem to share this opinion. The opening scene shows us King Kong lounging around, swinging on branches and being cool and likable. This movie doesn’t want you to forget that King Kong is a monkey, and monkeys are a lot like humans. Now, I’m not opposed to some King Kong humanizing! I’m not immune to his charms. But for god’s sake - show me Godzilla every once and a while!

Godzilla vs. Kong also features a television crew who films King Kong in some sort of Truman Show situation(?). I didn’t really get it, but the important distinction between this movie and the 1962 version is that the newer one tries to make human characters that the audience is supposed to like. This was annoying. Not one, but two storylines followed different groups of people - one of them featuring Millie Bobby Brown, of Stranger Things fame. Unfortunately, I found all of these characters to be uninteresting, and even the best of these characters, Jia - a young girl, native to Kong’s island - felt like a tired cliché.

And then there were the fights. This is, of course, the most important part of the film - all you know, going into either of these movies, is that King Kong and Godzilla are going to fight - and where, I think, the 2021 version failed miserably in comparison to its predecessor. Maybe they looked more epic or more “real” (they were certainly flashier and louder), but it was, at times, hard for me to tell what was going on. These fights were so focused on the special effects - how cool CGI King Kong and Godzilla looked (not that cool, really) - that the actual choreography of the fights were lacking. The zooms were so frequent that I couldn’t get oriented in the scene, and, sadly, Godzilla and Kong mostly just punched each other in the face.

Contrast this with the second and last fight scene in the 1962 film: King Kong is transported to Godzilla’s location using balloons, and dropped from the sky - he falls down a hill and takes out Godzilla while he tumbles. Kong knows that hurling rocks at Zilla do absolutely no damage, so he hides under a ledge and waits. When Zilla shows up, he can’t see Kong (he’s right behind you, silly!), and Kong takes a chance at grabbing Zilla’s swinging tail. It’s a failure! Kong gets swung around by its pendulum-ic power. In a desperate stupor, Kong forgets that hurling rocks is no good, and starts throwing, but Zilla turns around and uses his tail to launch a boulder back at Kong!

Okay, so I won’t detail the entirety of this fight, but needless to say: it’s creative. Coming off of the high of this epic battle, I was majorly disappointed to see Kong and Godzilla’s lacklustre brawls, even in IMAX. The creators of Godzilla vs. Kong knew that the technology had improved majorly since the last Honda version, and relied on that fact to make an exciting monster movie, but there is more to a film like this than special effects. The popularity of the kaiju movies of the 50’s and 60’s are a testament to that: sometimes, less is more.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Themroc” - The Satire That Doesn’t Need Language

“In order to seriously deal with ideas, one must create a new film language for expressing them.” - Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation

Although it was made by the french director Claude Faraldo, you won’t need subtitles for his 1973 abstract comedy, Themroc, because there is no discernible dialogue. This film focuses its attention on a man, seemingly in his late thirties or forties, who, one day, rejects all aspects of socially constructed norms and causes an uprising of similar behavior in his neighborhood. Although there are no words articulately spoken, there is a clear narrative facilitated by the actors using what may be the most accessible language to all human beings: grunts, moans, coughs and screams. What is left after words are removed? Cinema of pure emotion which calls into question foundations of daily life that humans take for granted, most significantly the way we communicate.

The life of the main character (is his name Themroc? The movie doesn’t make this clear) starts off as normal as anyone’s: by making coffee before going to work. During this process of making breakfast for himself, the main character coughs incessantly, the sound of which will become very familiar to the viewer by the end of the film, as it is one of the only noises he makes. A young girl wearing almost nothing passes in front of him, and goes into a room, and the older man follows after her. Their relationship is not clear, but the older man’s manner suggests that it is taboo for him to be sneaking into her room and smelling her naked body. Maybe they are brother and sister, or father and daughter.

These ambiguities in the plot highlight the language of cinema: the ways in which characters, scenarios and tones are created through camera movement and editing alone. While the main character is on his way to work, shots of his face are juxtaposed with shots of an older woman that lives with him gesturing towards the clock (an action that seems to happen everyday, as the main character recalls her in multiple different outfits), and shots of him passing by a young woman in the hallway of his apartment. Through this editing trick, the audience is able to ascertain that the main character is frustrated with the monotony of his life, is yearning for something different.

At his job, where the main character is part of a painting crew, is the first instance where gibberish in place of language is used. In the locker room where the men are getting dressed, a fight breaks out between two sides of the lockers. The camera pans back and forth between two “factions” separated by a row of lockers. Again, this camera movement helps establish different groups. It is not clear what the men are fighting about, since they are shouting “words” that cannot be understood by anyone, but it isn’t important to the plot what they are saying; the audience knows what is happening.

Over and over again, different types of gibberish are employed in different scenarios and by different people in order to convey something particular about them. When the main character gets arrested for spying on a man and a woman in a building, the police officers have a specific tone to their babble that suggests stupidity and dullness. In one deliciously satirical scene at the office of the policemen, a man with an apparently large amount of authority is shown sharpening a row of over twenty pencils, then a few minutes later, systematically breaking the tips off of each freshly sharpened utensils.

In the same way that, in this film, the gibberish utterances of characters are meaningless and signify nothing (besides, of course, raw emotion), the actions of the characters are not explained using any underlying motives and are basically meaningless as well. This is the state that the rest of the film inhabits: one of pure action - signifier without signified - in which the audience must either attempt to understand why, or else let the events unfold as they will. The main character appears to have some sort of mental break after escaping from the police and, with the young girl that he lives with - and is by this point having a full-fledged affair with - goes to a junkyard and collects a wheelbarrow full of bricks. He takes them home, and walls himself up into a room of the apartment, secluding himself from the older and younger women, then takes a sledgehammer and breaks down the outside wall, revealing himself to his neighbors and everyone on the street. He throws every piece of furniture in the room onto the streets, attracting much attention from the people below.

The neighbors across the street are inspired by the main character’s actions, and follow suit, breaking down their own wall and throwing their possessions back and forth across the street with the main character and the young girl, who climbed her way up to the room using a ladder. By the end of the film, the action devolves into a cannibalistic orgy in which new people are lured up to the room to have sex loudly in the public eye, and the characters are roasting and eating police officers. This open display of social deviance inspires many people on the streets below, including a man who has been painting his car for several scenes to take a sledgehammer to the automobile he clearly cares a great deal for. The final montage of sex and violence is interspersed with images of buildings, cementing this movie’s thesis about social constructions that serve to bring us closer together, yet wrench us farther apart, including the walls of homes and apartment buildings, and most importantly, the way we communicate. Language, instead of allowing humans to easily express themselves, has become convoluted and confusing, leaving emotions, the true depths of our being, far in the dust. Maybe we’d be better off just grunting.

0 notes

Text

“Tux and Fanny”: An Appreciation Post

The hardest part about learning to be an adult hasn’t been teaching myself to do taxes or figuring out car insurance policies - although those have been really hard - it has been trying to maintain excitement with tasks that I have to perform everyday, struggling to find joy in monotony.

Of course, an easy solution to this problem is to do new things. “Mix up your schedule!” they tell me; and I have, to a certain extent. But really, my schedule can only take so much mixing up before I’ve fundamentally changed the way I live: I have to work a set amount during the week, I have to eat a couple of times a day, and ideally I leave the apartment at least once every 24 hours. So, although a walk before breakfast instead of after lunch is a welcome change, it is still a walk around the same neighborhood which often leaves me feeling bored and unfulfilled. Who can get excited about getting out of bed in the morning when the day doesn’t greet you any differently today than it did yesterday?

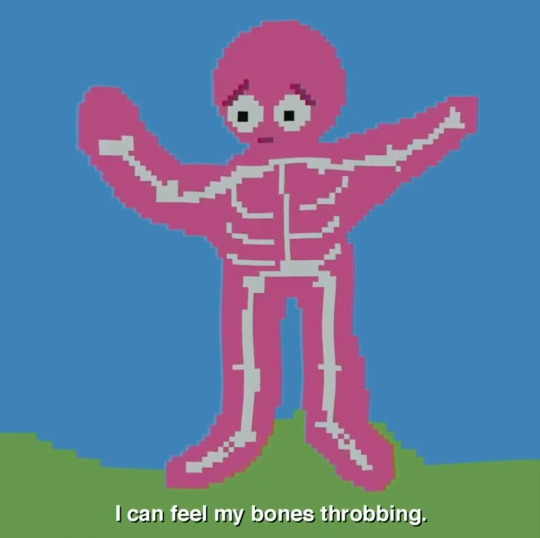

Alas, there is always a new movie to watch once the sun goes down. A recent dive into the world of Letterboxd lists introduced me to Albert Birney’s Tux and Fanny, a compilation of 79 1-minute long animated shorts originally posted on Instagram. The description reads: “Tux and Fanny are two friends living together in the forest and these are their adventures!” Being a notorious lover of all things fun (especially when they only take 82 minutes of my time), I was hooked. The concise blurb and pixel-art style led me to believe that it would be a simple, entertaining watch - which it was! What caught me off guard was the emotional depth of the characters, and the ways in which the film explored mundanity and absurdity with an equal amount of weight and humor.

Tux and Fanny does exactly what it promises: follows two characters named Tux and Fanny through a whole lot of day to day activities, although it would be a stretch to call most of them “adventures.” Tux is pink and speaks in a lower voice than Fanny, who is purple. They live in the same house in a forest and sleep in separate beds (in the same room). Beginning with a very basic premise, the film goes to some pretty bizarre places. The first segment shows Tux and Fanny kicking a soccer ball back and forth in their yard when a black cat walks up. Tux wants to bring it inside, but Fanny worries that it might be flea-infested. They bring it inside anyway, and it turns out the cat is infested with fleas. Thus begins the first conflict of the movie: how to stop the itching? The internet sayeth: Peanut Butter! So, our protagonists lather themselves with peanut butter, and: sweet relief. But how to get it off? While Fanny opts for the ol’ hose technique, Tux goes a different route: “I’ll lay down on this ant hill and feed thousands.” Unfortunately, the ants not only eat the peanut butter off of Tux’s skin, they eat his skin, too.

Peppered among these absurd situations are moments when Tux or Fanny pauses and ponders a lofty philosophical question. Covered in peanut butter, Tux picks up a dandelion and says “Look at the shape, the structure. Millions of years of evolution has brought it to this design. These gentle pilgrims will disperse to the four corners of this vast universe. Fanny, we are like these seeds. The day will also come when we must float away and seek our destiny.” He promptly blows the seeds away which inevitably land on Fanny and stick to the peanut butter on her skin. It is juxtapositions like this one that help bring comedy to lofty topics like eternity, while injecting some much needed wonder into seemingly dull moments.

Aspiring to a world view like Tux and Fanny’s would probably be unsuccessful and maybe even undesirable, but there is certainly something about the way they interact with their day to day activities that struck a chord with me at this moment in my life. The fact that Tux can still see beauty in things like “the sunlight through the leaves, the sun dappled grass,” and “the butterflies, so light and free” when he is a literal skeleton is truly inspiring. I have been at a place in my life when everything looked new, and every day gave me a novel insight. It pains me to acknowledge how fleeting the feeling of awe can be: how do I get it back once it’s gone? Is it just a part of getting older?

The film raises more questions than it answers, like, “are Tux and Fanny humans?”, and “Why can’t they go to the store to get food if they’re hungry?” Maybe they can go to the store - where did they get the peanut butter in the first place? - but these characters constantly turn to absurd solutions for simple problems (like keeping a chicken trapped inside of Tux’s ribcage as a source of food). More often than not, Tux and Fanny are involved in situations that seem drenched in mundanity, like eating turkey on Thanksgiving, standing outside on a windy day or playing a computer game, yet inevitably take a turn for the absurd: the growth hormones in the turkey cause Fanny to grow extra limbs, Tux gets whisked away by the wind, and Fanny gets sucked into the computer when lightning strikes the house. These instances offer a new perspective on the tedium of adulthood. There is always a new way to see things.

Even if I can’t live just like Tux and Fanny (would I even want to?), I can learn lessons from their attitudes. “What if for every grain of sand here, there exists another universe out there. And in each universe, there exists another version of us.” “That’s a lot of us. If we do exist out there, I hope we have sunsets.” To display reverence for the small, and nonchalance towards the lofty. Why should I entertain ideas I can’t comprehend but ignore the richness of my immediate surroundings? The best lesson I can take away from this silly, hilarious and beautiful movie is to slow down and appreciate each moment as I live it. I may be able to notice something I’ve never seen before.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Videodrome” and Humanity’s Technological Evolution

I think that massive doses of Videodrome signal will ultimately create a new outgrowth of the brain that will produce and control hallucination to the point that it will change human reality. After all, there is nothing real outside of our perception of reality, is there?

In 2020, many people saw their daily activities rapidly shift from in person to, suddenly, being mediated by a screen: not only meetings with coworkers, but holidays, education, concerts and even grocery shopping. This has been shocking to many, and it should be, since it represents a new way of interacting with the world being grafted onto humanity, almost like a brand new digital organ. A decade ago, you could get along fine without a cellphone, but now, everything from our friendships to our money seems to be moving towards the technological. These frightening observations may seem better suited to a science fiction novel, but they have been around much longer than the iPhone: I found them at the forefront of David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983)!

Videodrome is a movie about augmenting our humanity and our reality using technology. Sound familiar? This film came out almost forty years ago, and it shows - the accepted medium for sharing videos is VHS - yet it still has much to say about the age of the internet, and our relationships with our devices. The audience follows Max Renn, the CEO of a small, smutty television station, as he searches for new, shocking programs to air that will attract viewers. With the help of a “pirate” (no, this isn’t thepiratebay) who uses a satellite dish to lock onto and record television broadcasts from all over the world, Renn becomes familiar with a show called “Videodrome”: a plotless exhibition of torture and muder.

What is unclear, and here is where Videodrome becomes conceptually fascinating, is whether or not the depictions of death in this program are simulated or not, and whether or not this matters. Renn is advised to seek out Professor Brian O’Blivion about his inquiries into Videodrome, and finds that the man only appears on television - never in person. O’Blivion’s daughter gives Renn a VHS tape to watch in which the professor pontificates thus: “The television screen is the retina of the mind’s eye. Therefore, the television is part of the physical structure of the brain. Therefore, whatever appears on the television screen emerges as raw experience for those who watch it. Therefore, television is reality. And reality is less than television.” Renn scoffs at these statements, as many audience members might, yet this line of reasoning is both provocative and valid.

What is experienced by characters in television programs is experienced vicariously by viewers, although differently. This fact creates within viewers a novel and unique reality that exists both on the screen and within their minds. This concept isn’t specific to television; books can have a similar effect, but we interact with words on a page much differently than we do real-life images on a screen. Hearing people speak, seeing them smile, watching them die, all have a much heightened level of reality in comparison with staring at text. But to what extent is Professor O’Blivion correct when he says that television is more real than reality?

Technology allows its users to exercise a heightened level of control over their own identities. It is revealed that Professor O’Blivion is dead, and has been for almost a year, but he lives on through his tapes. He still makes television appearances, and has conversations with people. His daughter remarks that “at the end he was convinced that public life on television was more real than private life in the flesh.” O’Blivion died of a brain tumor, that he claimed were caused by “video hallucinations” - a product of watching Videodrome. Max is informed that, since he has seen Videodrome, he is also growing a brain tumor caused by his hallucinations. These visions are what allow Brian O’Blivion to communicate directly with Max - he refers to him by name, and advises him on his specific problem. He has literally been able to transfer his being to the television realm, and continue to exist beyond death.

The internet does not allow us to exert this amount of control over our existences - not yet, that is - but people are able to present certain sides of themselves online that they may not show in person. The television show Catfish brought this particular trend to the public’s attention: there are plenty of people out there that are manipulating their internet presences, and sometimes straight-up lying about who they are, all while creating relationships with people who are ignorant of the “truth.” This is where Professor O’Blivion would tell us that other people’s perceptions of a fabricated identity online were just as real as a person in the flesh. Most people don’t abide by this logic, and are hurt when they feel that others are lying to them; O’Blivion’s perspective points to a new era of humanity that would exist entirely within screens, and be dominated by hallucinations. In other words, this new existence would allow humans to control what they saw, and how others saw them: controlled hallucinations, or, simply a manipulation of reality.

When reality is this malleable, there enters the concern of who is in control? Brian O’Blivion’s old business partners who sabotaged him enter the narrative as the antagonists, who have an evil scheme to use Videodrome as a destructive force. Of course, this is Cronenberg, and with augmented reality comes augmented physicality; Max Renn is able to open up his stomach and store things inside of himself, additionally allowing VHS tapes to be inserted in him like a video player, controlling his actions. “They can program you. They can play you like a video-tape recorder,” O’Blivion’s daughter (Bianca) tells Renn. Luckily, Bianca is able to help Max de-program himself (in an awesome scene where a television screen literally mirrors his torso), giving him a new objective and catchy tagline: “Death to Videodrome. Love live the new flesh!”

Renn’s triumph over those who would wish to make a robot assassin out of him is an encouraging look at the new age for the modern viewer. Things aren’t as cut in dry in a world where physical media has become virtually obsolete. How can I know if I’m being controlled by my devices, and to what end? To what extent have my devices become an outgrowth of myself, in the same way that video hallucinations cause brain outgrowths in Videodrome? As we spend more and more time interacting with screens, it may become necessary to step back and ask ourselves where this relationship is headed, and whether or not it’s positive. Brian O’Blivion was incredibly optimistic about “the next phase of man as a technological animal,” that is, until the wrong people took over for the wrong reasons. Maybe the question we should be asking in addition to “Do I want to see human evolution continue down this path?” is “Who is in control of this path, and why?”

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rob Savage’s “Host” Is Innovative Zoom-Horror

The first time I saw The Blair Witch Project with my sisters - none of us any older than 12 - and my dad, the scariest part about it was that my dad told us that it was real. This gimmick is what sets found footage films apart from other movies that make no claim to reality, and why they can only thrive within the horror genre: their implications are legitimately terrifying.

Now that I’m older, I don’t fall for the premise that all found footage movies try to scare you with - that this actually happened - but I do have a sincere affection for them. I saw the first three Paranormal Activity movies several times while I was in elementary and middle school, upgrading to Patrick Brice’s Creep when I got older, along with a slew of other less memorable features with the same general idea that something scary is happening and someone involved (for whatever reason) is filming it. These movies are unique, often low-budget, innovative, and often short in runtime, since, at a certain point it doesn’t make any sense for characters that are in danger to continue holding a camera.

In a lot of ways, horror that takes place entirely on a computer screen, of which Rob Savage’s Host is a part, feels like a logical progression of the found footage genre. In an age where more and more of our lives are mediated through technology, it is exciting to see filmmakers embrace new opportunities for experimenting with storytelling in all of the forms it can take. Host is certainly not the first of its kind (video-chat horror has been around since the early 2010’s), and most reviews for this 2020 release can’t help but mention its 2014 predecessor, Unfriended. While I haven’t seen Unfriended, I have seen The Den (2013), and was very impressed with Host’s use of Zoom-specific features to create scares, and its production and release during quarantine emphasizes human and spiritual connection through the internet in a way that is interesting and effective.

The film takes place entirely during a Zoom call between six friends, one of which has come up with the idea that they should conduct a seance together over video chat. Two of the participants are nervous about the process, while the rest of the friends seem incapable of taking it seriously; one of them proposes that they take a shot each time they hear the term “astral plane.” After a short section at the beginning in which the characters chat mindlessly and catch up, the woman who is supposed to guide them in the seance joins the call. She admits that she has never done this before over a video call, and that it might make them more vulnerable - to what, she doesn’t mention.

Like any movie involving spirits, there is pressure by a few that these matters must be treated with reverence in order to show respect to the dead, but inevitably, there are those who make a joke out of it. After one of the friends leaves the meeting while everyone is supposed to be focusing, things are looking grim. They only get worse when one girl, Jemma, makes up a story about a schoolmate that she knew who hung himself named Jack. This becomes, according to the leader of the seance, a mask that any type of spirit can wear; an invitation to manifest itself. To me, this was a very clever way to introduce a potentially demonic presence which I hadn’t seen before in my paranormal forays, providing a simple image around which the movie’s scares can revolve, while making the spirit eerily unknowable.

Once the jump scares start, they don’t stop, and while at a certain point I felt that they were becoming repetitive, the 56 minute runtime saves this from being a problem. And a lot of it is damn scary! The parts that were the most fun, though, were the Zoom gimmicks: one in particular stands out in which one of the characters, Caroline, shows everyone the background that she made - a video of herself in her bedroom walking in and brushing her hair - in order to combat quarantine loneliness. After all of the girls are convinced that they are safe, Caroline disappears from her screen for a moment. By the time the others notice that she’s gone, her specially crafted background starts moving: an image of her walks into the room. The girls think that Caroline is actually there and try to get her attention. Attentive viewers may remember that what they are calling out to is merely a phantom of Caroline, creating a moment of tension that is unique to the medium of Zoom.

At the same moment that Caroline’s face breaks through the background for only long enough to smash the keyboard and disappear again, Emma, who has been playing with filters on her face for most of the call, sees a computer generated mask floating in her living room. Of course, she can’t actually see the mask, or what it’s being generated by, anywhere outside of her computer screen. The webcam has become an eye through which extra information about the world can be observed.

Although Host is by no means the first within its genre, these computer-based scares are where the movie shines. Especially given the circumstances of its production and release, the themes of connection of all kinds through electronic devices are particularly timely. The movie was released in July of 2020, and made while the director and actors were actually quarantined due to Covid. Rob Savage directed all of the actors remotely, and everyone was responsible for their own lighting, cameras and stunts. There seems to have been no better time to make a movie like this, when viewers are all too aware of the mechanisms and social cues that dominate virtual conversations.

And what better time to explore all of the things - good and bad - that can be shared over the internet? No, luckily, we can’t exchange germs, but apparently we can pass spirits from one household to another. After shit has been critically hitting the fan for about fifteen minutes, Teddy, the character who abandoned the Zoom call just as the seance was starting, reappears. Emma, the only girl who is still active in the call at this point, urges him to “get out”, but he doesn’t take her seriously and almost immediately gets visited by the same spirit that has been tormenting his friends. He was evidently fine before he rejoined the call, but, like a hacker tracking down your IP address, the (demonic?) presence was able to visit Teddy in his home just because he connected to his friends over the internet.

So, while I didn’t consider Host to be the best found footage film I’d ever seen, I think it utilized its form extremely well, and brought fresh ideas to the genre that could only be played with at this moment in time. The webcam movie may well become tired within the next couple of years, but, to me, it is still a lot of fun. I’m looking forward to seeing Unfriended, but for now, would recommend this movie for a short, scary, quarantine pick.

0 notes

Text

“The 400 Blows” and the Radically Personal

Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel in The 400 Blows

François Truffaut’s debut feature, The 400 Blows, may not exhibit the avant-garde tendencies of those filmmakers who completely disregarded narrative (and even visual!) “rules”, but, unlike the creators of most Hollywood blockbusters, he centered his focus entirely on the personal. The film follows Antoine Doinel, a french schoolboy whose narrative mirrors many biographical details of Truffaut himself. He is shown struggling to behave at school, and mostly failing to win his parent’s affections at home. As the movie progresses, more and more details about the parents’ pasts are revealed, and eventually they decide that they don’t want to (or cannot) live with him anymore, and he is sent to a camp for juvenile delinquents.

While the narrative is fairly straightforward - an easy way to criticize any French New Wave film’s claim to avant-gardism - Truffaut’s portrayal of Antoine is intimate in a way that only personal cinema can achieve. The first scene is centered in the classroom - one of the main locations for the film - and shows a young student pass around a lewd picture of an older woman while the kids are supposed to be writing. When the picture gets to the main character, he takes his pen and draws on the photograph. Inevitably, he is the one that gets caught by the teacher, and must stand in the corner, even through recess. This seemingly trivial moment in the life of a young boy has the distinct mark of memory written all over it, especially in the way that children often perceive negative events: as things that happen to them, without their influence.

Truffaut’s affection for youth is most apparent in these classroom scenes. The schoolteacher, only ever referred to as “sourpuss”, is afforded long, boring scenes in which he writes poetry on the chalkboard that the boys are intended to copy, while the children make a mockery of him behind his back. While special attention is paid to Antoine, in the first ten minutes of the film, Truffaut doesn’t hesitate to fix the camera on other students - one in particular stands out, who is given a full minute of screentime to accidentally smear ink on one page after another, until he has ripped out nearly every page in his notebook - with fondness.

The other location that is featured at length is the apartment where Antoine and his parents live. The scenes that take place here are often banal - taking out the trash, gossip-filled conversations at dinner - yet their specificity grants them a certain realness that is part of this movie’s charm. How many of the scenes are fabricated it is hard to say for sure, but the success of this film rests on the fact that - maybe owing to Truffaut’s personal knowledge of the story - the characters and events are alive. Verisimilitude of this degree may be considered the antithesis of experimental cinema, but in the world of mainstream movies where stories are created and distributed solely for profit, a confessional movie like The 400 Blows should be considered subversive.

Truffaut’s emphasis on the personal culminates with the final scene, in which Antoine runs away from the camp for juvenile delinquents during a game of soccer. After a lengthy shot following the boy running through down a street in a rural community, Antoine finds himself at the ocean - which, earlier in the film, he told his friend he had never seen. He runs through the water in his shoes, and walks up to the camera, looking directly into it. Again, this is not formally an experimental film; this is not some cheap cinematic trick. Through the eyes of Antoine Doinel in the last shot, and even throughout the narrative, Truffaut reaches out to the audience, dying to be heard, trying to tell his story and let it be heard as his own.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Publicity in John Waters’ “Serial Mom”

Second only to his love of portraying freaks on screen is John Waters’ obsession with publicity. Although no one can forget the second to last scene in Pink Flamingos in which Divine invites “the press” to the trial and murder of Connie and Raymond Marbles, and they thank her for the good story, his 1994 feature Serial Mom shows an increased awareness of the dangers - and comedies - of America’s mass proliferation of sensational images and stories.

From the very beginning, the film is obviously intended to be a biting satire of American suburbia, at the center of which is a mother who, to the public, refuses to say an inappropriate word, won’t allow chewing gum in her house, and is an adamant recycler; but who, in her private life, harasses her next-door neighbors with obscene phone calls and letters, and very easily makes the decision to murder her son’s math teacher over an insulting remark. The audience doesn’t see Serial Mom’s descent into madness: Waters presents it as if it were there all along, maybe even looming underneath the mattresses of many “sane” housewives.

Serial Mom harassing her next-door neighbor, played by Mink Stole

The PTA meeting dispute that sets off Serial Mom’s fury consists of her son Chip’s math teacher remarking that Chip is obsessed with horror movies to a disturbing degree, and that this obsession reveals that she has done something wrong in raising him. This sentiment lies at the very core of Waters’ exploration of the effects of media in this film: what has violence, placed so prominently in the public eye, done to its psyche? Of course, this film doesn’t answer this question directly, and often approaches it more jokingly than would be preferred (but, really, what else can you expect?); Waters makes fun of everyone in this movie, from the cloistered suburban family to the excessively violent punk band, and leaves you feeling that no one is safe from being poisoned by publicity.

This is, to a large extent, what Waters seems to be going for here. One of the most poignant moments is when Chip, who runs a video store with his girlfriend, encounters an unpleasant customer who refuses to rewind her VHS tapes when she returns them, despite store policy. When his girlfriend calls her a bitch after the woman leaves the store, Chip says, “It’s the influence of all those family films,” subverting the trope that the movies that you watch directly influence your actions (it’s even funnier remembering Matthew Lillard, who plays Chip, and his role in Scream). Chip and his girlfriend are not violent, despite their genre inclinations, but it does affect how they react to the murders going on. When Chip’s girlfriend, Birdie, first hears that their math teacher has been killed, she calls Chip and says, “This is so cool, it’s just like a horror movie!”

Chip, played by Matthew Lillard, in his horror fanatic bedroom

These types of reactions to Serial Mom’s crimes are numerous throughout the film, and constitute a larger part of Waters’ interest with publicity than whether or not violent imagery creates violent actions. Serial Mom light-heartedly explores the ways in which violent movies, true crime novels, and television influence our responses to violence in real life. When Chip’s sister begins to suspect that their mom is a murderer and tells him about it, Chip responds with, “That’s a cool idea, Misty. Hey, let’s make a gore movie about mom!” Serious, emotional moments are turned into opportunities for publicity, when the brother of one of Serial Mom’s victims accosts Chip at her trial. Instead of engaging with him, or attempting to make reparations, Chip asks if he’s signed off yet, and they discuss who’s going to play who in the movie version of the events. Serial Mom’s daughter Misty also capitalizes on the situation, teaming up with a reporter to sell novelizations and “Serial Mom” t-shirts outside of the court.

But what influences Serial Mom to kill people? Waters never explicitly answers this question. Although a treasure trove of true crime books are found in her possession, it’s not clear if that reading interest came before or after the psychotic break (if there was one). This ambiguity underscores what Serial Mom markedly avoids: serious condemnation. John Waters isn’t trying to say that watching gory movies will turn you into a criminal - he loves gory movies, too! At its heart, this movie is a light-hearted, comedic exploration of what could be very serious topics; but that’s for a different director to make.

14 notes

·

View notes