Welcome to the Picturebook Makers blog – where the world's finest picturebook artists take you behind the scenes.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Fanette Mellier

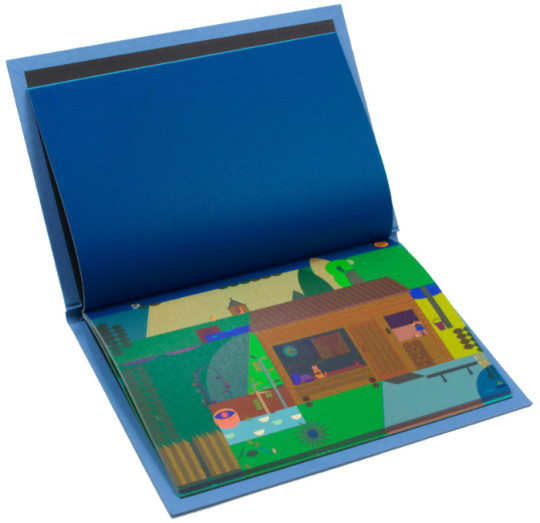

In this post, Fanette talks about the creation of her picturebook Panorama, an ingenious visual feast in which layers of ink reveal the subtle yet intricate changes which occur over the course of one particular spring day.

Visit Fanette Mellier’s website

Fanette: My book Panorama was conceived in a unique way. It reflects an event in my personal life: the acquisition, along with my husband Clément, of a small chalet not far from Paris, where we live. To us, this place represents a "dream location" nestled in the heart of "no man’s land", the one and only we own.

I wanted to build Panorama around what this place represents, both materially as well as metaphorically. For a long time, I wanted to create a truthful and exclusive colourful narrative. In reality, the story of the book isn’t really about the chalet, it’s about the colour.

As with my other works, I began by sending a letter of intent to my publisher Alexandre Chaize. This letter referred to the definition of the word panorama:

• A circular picture painted in optical illusion. • A vast landscape that can be seen from all sides. • A succession of images perceived by the mind as one complete visual experience.

It also included the following intentions: The book follows in the footsteps already explored at Éditions du livre (cycle, colour, temporality, composition in sections, title volatility, absence of words...). But the project takes on a slightly more illustrative dimension, providing a pretext for exploring the form (unchanging) through the colour (whereas in Matryoshka, the form also evolves). So it’s a more detailed and narrative experiment, but also a more radical one. The overall form (shaping) is simple, but reverses the reading, in a vertical dimension.

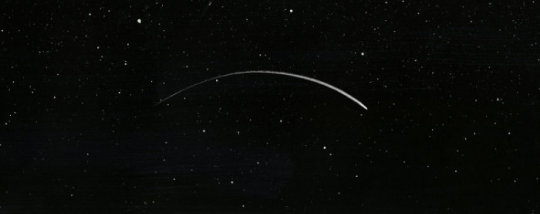

On the publisher’s website, you’ll find this text, which sums up the book’s intentions in retrospect: “Panorama invites us to contemplate the same landscape, printed 24 times. Page after page, the colour variations reveal the passing of the hours and micro-periods of life. From the gentle warmth of a spring afternoon to the frost of night, nature awakens and then falls asleep. Observing the details becomes a child’s play: a chalet, a clock, a cat, a balloon, a glistening green... Fanette Mellier creates a world where ink layers draw a subtle and dizzying horizon.”

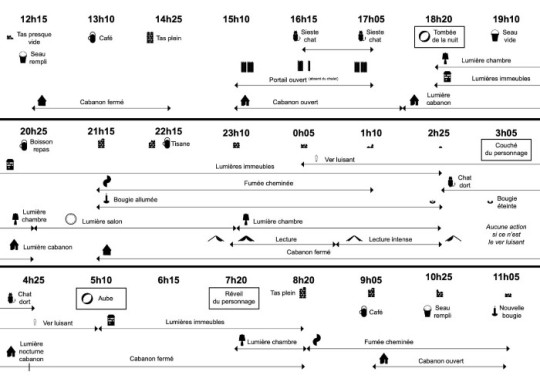

While I was working on the drawing, which took several weeks, I made progress on the synopsis of the book by writing all the narrative passages in advance, hour by hour and page by page. These passages correspond to the colour changes of the various elements, which are described in detail in my notes.

This synopsis was the subject of many discussions with Alexandre, who went so far as to create illustrations in order to check that the narrative flow was consistent.

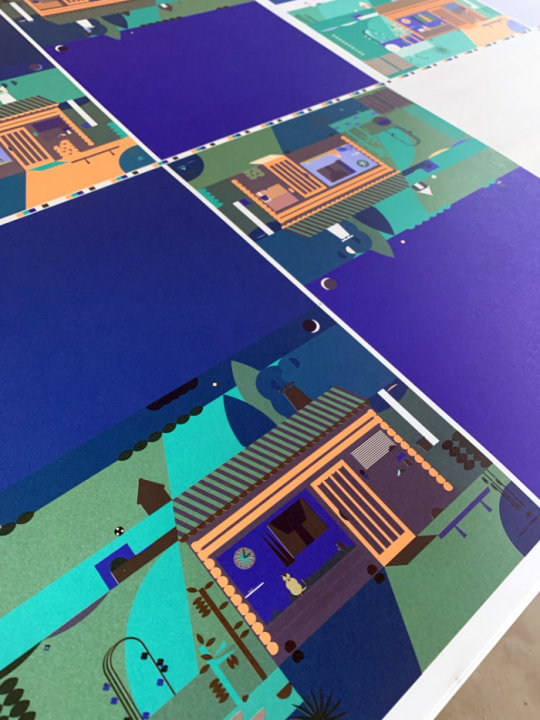

Then, once the layout of the book had been completed (which was a very tedious phase!), I was involved in the final layer setting at the Art et Caractère printing house in Lavaur. Printing the book, which was supposed to take a day, took more than three, and I thought we’d never get to the end of the final layer setting... to the point where it seems to me that it would be out of the question to reprint the book one day.

Panorama is printed in a special way, as it is a mixture of four-colours and direct shades. The four-colours, in their "standardised" aspect, are used as a realistic coloured canvas.

The entire landscape was coloured beforehand in CMY, to form a chromatic base. The CMY inks were therefore printed first during the layer setting.

The 3 Pantones, black and white were then printed in stages. The Pantones correspond to the narrative: PMS 807 brings light, PMS Green intensifies and nuances the presence of green, and PMS 072 brings the night and refreshes the landscape.

Black is only used on 6 pages, between 12.05am and 5.10am, to vividly draw in the night shadows. White takes over from black. Between 6.15am and 11.20am, it brings the colours to life with a morning frost that gets lighter over the pages.

The complexity in terms of printing comes from the intersections and overlapping of the colour zones, because printing in several steps causes the paper fibres to move and makes it difficult to reproduce these mixtures of colours on a very fine scale...

To me, the result of this book is halfway between the impressionism of Water Lilies and In Search of Lost Time on the one hand — and the pop art of Maya the Bee and Où est Charlie? (Where’s Wally?) on the other...

The book has become such an integral part of my life that I often feel like I’m walking around “in my book” when I’m at the chalet.

And a strange thing to mention is the presence of animals. The main character in the book, the cat, was completely fictional when I wrote the book. After the book was published, he arrived and settled down overnight in the same place as in the book, in front of the window. This cat, who’s called Austin and belongs to the neighbours, always comes by when we spend time in the chalet. The frog and the glow-worm have also appeared over time, in the same place as in the book. It gave us goosebumps!

This permeability between the real world and the book has a mystical resonance to me.

Illustrations © Fanette Mellier. Post translated by Gengo and edited by dPICTUS.

Buy this picturebook

Panorama

Fanette Mellier

Éditions du livre, France, 2022

Panorama is the contemplation of a single landscape printed 24 times, once for each hour of the day. Page after page, the changing colours reveal the passing hours and the little miracles that are part of any given day in a life.

0 notes

Text

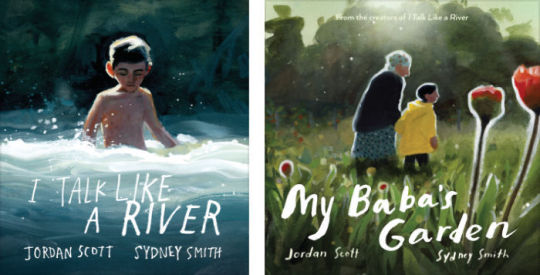

Sydney Smith

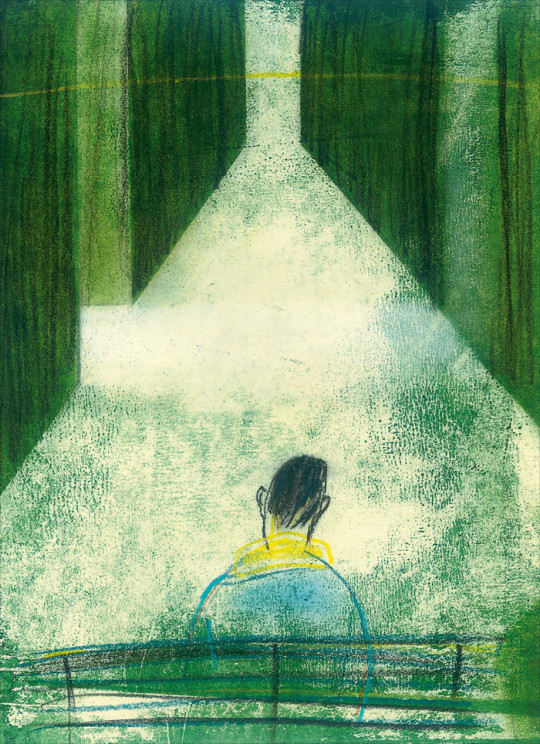

In this post, Sydney talks about Do You Remember?, a contemplative and deeply moving picturebook, told from the perspective of a young boy who is moving home and is trying to understand his emotions. To be published by Neal Porter Books in October 2023.

Visit Sydney Smith’s website

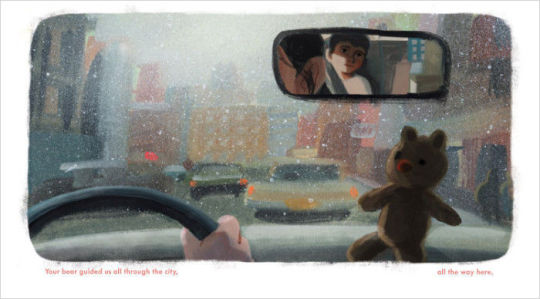

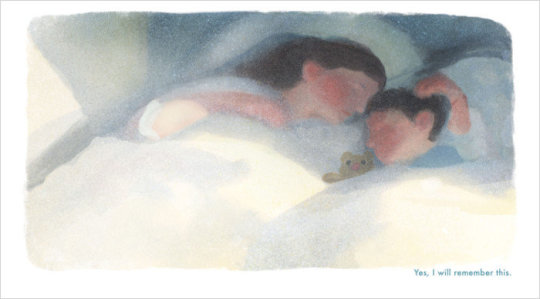

Sydney: At this moment I am sitting on my doorstep waiting for a book to arrive in the mail. I am waiting for that complicated moment of holding something in my hand that is final and limited in its form. Something that had filled my days, months, and years and brought more struggle than I expected and uncovered more of myself than I was prepared to face. It started as a book about memory. I should’ve guessed I was in for a challenge.

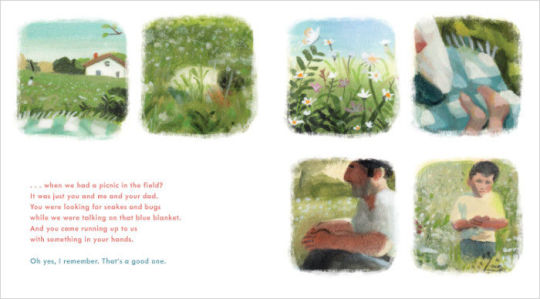

I had experimented in past books with painting softly and playfully. Those images looked like how a memory might appear if we could project our mind on a screen and show others that time when we were young.

Memory is something that is inherently personal and private but universal. As a visual artist I could try to communicate that feeling and the look of a memory. I wanted to speak to readers about the nature of memory, but I soon found out that I was swimming the deep end without my water-wings. It is vast area of the human experience, and I was unsure about my ability to tell an interesting story and relate it to the theme to which I was committed.

Hindsight tells me I was going about this all backwards. Starting with the theme and trying to fit a story to that theme requires too much forcing and manipulation and often makes for an awkward and stilted flow. I was not alone on this journey, my Virgil was my editor, Neal Porter. He gave me the freedom to explore and with every draft we shared we went deeper into the weeds, all the while Neal asking the only real question worth asking, “What is it about?”

It was a book about remembering the past and making a memory of the present with someone you loved. But the characters, a mother and son, were sharing memories that were mine. They were real memories about living in the country, about picnics in the field, and riding my bike on the driveway then leaving all that behind and moving to the city. The two characters are in a bedroom on the first night in a new home in the city far from the farm. The book was working but I couldn’t even look at it. It felt deeply wrong. I was omitting a major element of the story, of my story. The part that made each memory worth recalling.

What actually happened was my parents divorced and my mother and I relocated far from our home in the country. Everything was uncertain and my world was turned upside down. My mother still calls it the Great Upheaval. I knew that if the story wasn’t true to our experience, I would be denying a part of my history even though it was painful to everyone involved. At the time of the divorce my role was to convince those around me who were in such pain that I was unaffected and stable. I understood that my sadness would make others sad. I felt like a custodian for the emotions and guilt that surrounded me. As the book evolved into a story of a broken family, I understood that my feelings of discomfort were there because I was pushing against the instinct that formed when I was that 8 year old. I was showing my sadness and it was ok. But that was not all. I was also answering the question my parents have silently asked for 36 years. It’s the same question I am asking now with children of my own. What will you remember? What will your memories of this time look like? Will you remember the upheaval, the darkness, the uncertainty?

The answer is that I remember love. Unconditional and ever present.

This book is for my mother, but she has not seen it yet. I am sitting on my doorstep, waiting for this book to arrive in the mail. With its 40 pages and a handful of words, it could never say it all but it says enough.

Illustrations © Sydney Smith.

Buy this picturebook

Do You Remember?

Sydney Smith

Neal Porter Books, United States, 2023

Can you hear the morning wind in the trees? Can you feel the snowflakes landing on your wrist? Can you taste the sweetness of the warm berries?

A boy describes the memories that are so meaningful to him as he is about to move into a new home. Sydney Smith takes us into the mind of the boy as he processes the complex emotions that he experiences as he contemplates his new surroundings.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

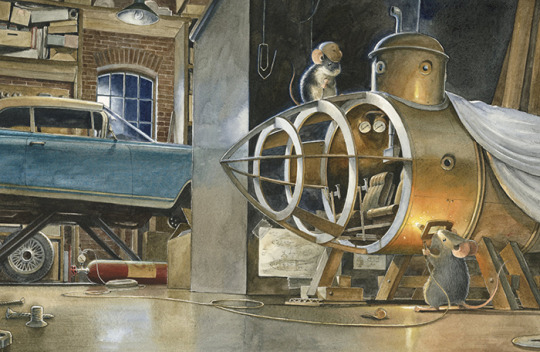

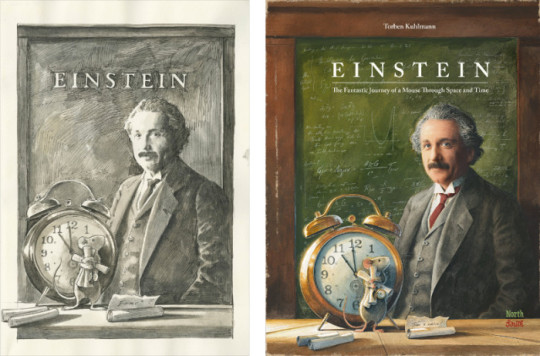

Torben Kuhlmann

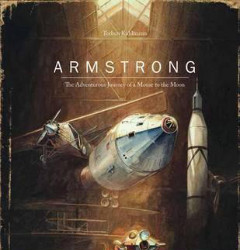

In this post, Torben talks about the creation of his mouse adventures: Lindbergh, Armstrong, Edison, and Einstein. Originally published in German and English by NordSüd and NorthSouth, this incredible series has been translated into over thirty languages.

Visit Torben Kuhlmann’s website

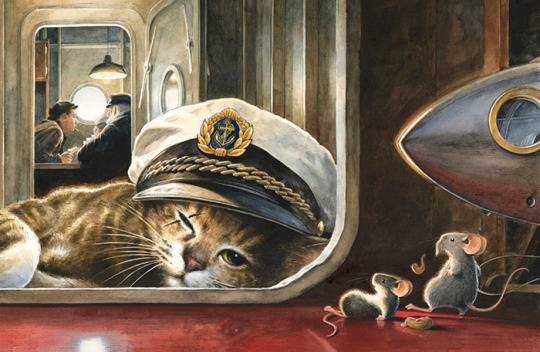

Torben: It’s been eight years since my mouse adventures series started with the book Lindbergh.

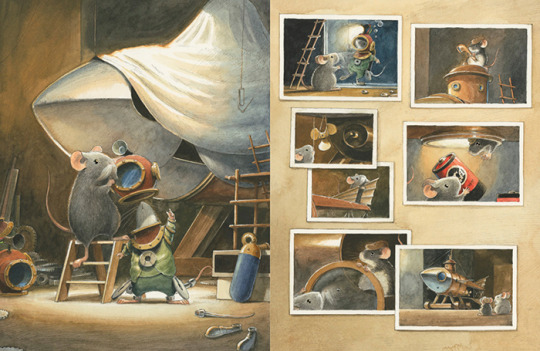

A lot has happened since then and three other inventive mice have had even greater adventures in my books: Armstrong, Edison, Einstein.

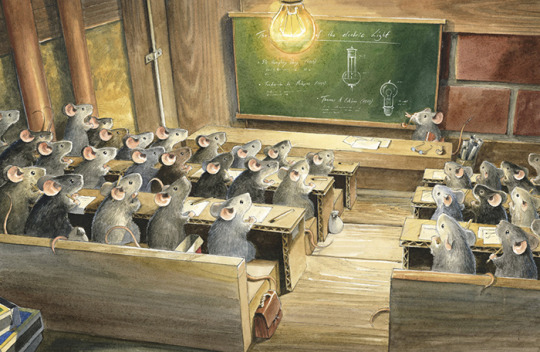

However, a few peculiarities are the same for all mouse adventures. At the beginning there is always the big question: What if...? What if many great pioneering feats and achievements in human history were actually the work of ingenious mice?

That thought was the starting point for Lindbergh and along with it came creative decisions that have defined the series ever since. One goal is always a degree of realism. I see a special appeal in drawing a realistic portrait of a bygone era.

And on this realistic stage, I tell the fantastical story of mice influencing human history in hitherto unknown ways, for example: by inspiring a famous pilot or a Nobel Prize winner in theoretical physics.

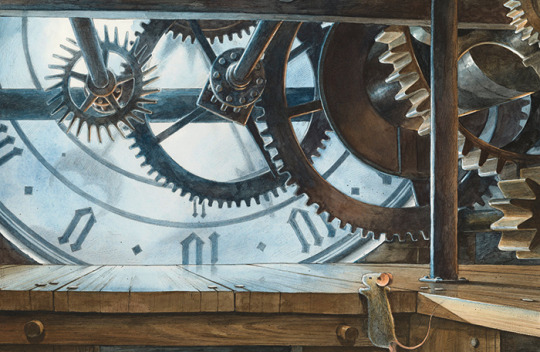

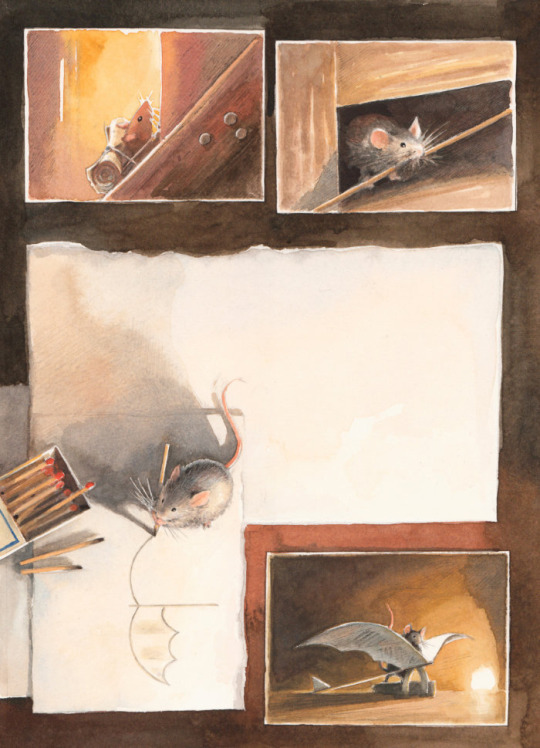

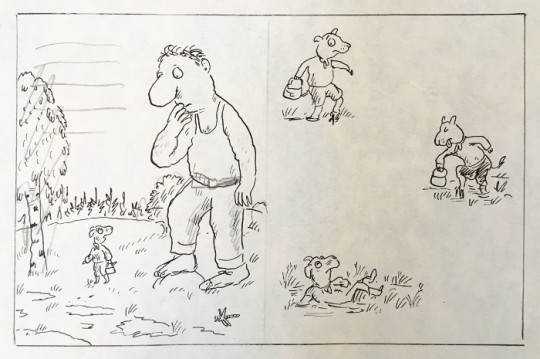

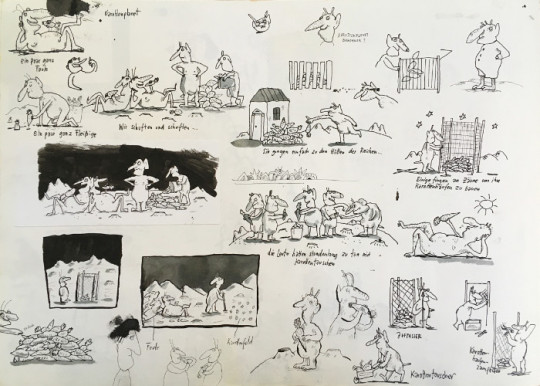

At the beginning of my process stands a sketchbook. The first task is to find some key scenes. Most of the time, a rough overall picture of the story emerges quite quickly. In Lindbergh it was a mouse’s meeting with a bat that got everything rolling.

The first sketches depicted that encounter and were soon joined by the mouse’s first inventions: flying machines that were clearly inspired by the anatomy of bats.

I then develop the concept further throughout the sketchbook and collect ideas in the form of rough scribbles, story bits, and early text ideas. Gradually, a typical storyboard emerges from this, not dissimilar to that of a movie.

My latest mouse adventure, Einstein, was also created this way, although the process was much more streamlined compared to the rocky start with Lindbergh. In Einstein the initial question was: What if a time-traveling mouse had inspired Albert Einstein’s thoughts on the relativity of time? Unlike the previous books, however, it was clear from the outset who would be the namesake of the story. And so the first sketches were portraits of a young Albert Einstein with a mouse hiding from him.

The topic of time and time travel is also indicated here visually, since several clocks appear in the picture. These first sketches later became the cover illustration. It was a nice opportunity (and a challenge) to have the namesake finally appear as a portrait on this latest book cover.

In general, the appeal of this fourth mouse adventure was the opportunity to play with paradoxes and time loops; something that is only possible thanks to the time travel theme. Within the story, the mouse—seeking to build a time machine—is inspired by Einstein’s work. And in turn, a young Einstein—writing his theories about space and time—is inspired by the mouse who is stranded in the past. It’s both a causality loop and a paradox if you think about it. A complete storyboard of the story developed very quickly in my sketchbook.

One idea quickly led to the next. It was very satisfying to see how these pieces of the puzzle emerged and gradually fit together: a late arrival to a cheese festival in Bern, stories of Swiss watchmakers, and last but not least Einstein’s Bern miracle year in 1905.

In addition to completing the sketchbook, work on the final text begins, first in handwritten sketches and gradually in a refined form. In the final picture book, the text and images should fit closely together. I often allow the illustrations to take on the narrative focus. Why should I repeat something in the text that can easily be observed in the pictures?

The last step is to create the illustrations. I use a combination of several techniques here. It begins with a pencil drawing on watercolour paper. This drawing is worked out more and more precisely and finally executed with waterproof ink. This drawing is then coloured layer by layer with watercolours. For a 128-page book, 64 double pages have to be planned and illustrated. But it is all the more fulfilling when all the elements come together in the end and you see the result of the work that has occupied you for a solid year.

This is a good moment to announce that the series of mouse adventures is far from over. I am playing with some early ideas at the moment. Let’s see which one will grow into a new picture book. There are still many groundbreaking inventions and pioneering acts that might have some as-of-yet unknown connections to inventive and inquisitive mice.

And slowly but steadily the 10th anniversary of Lindbergh is approaching. Let’s see what the ingenious mice have up their non-existent sleeves for that occasion.

Illustrations © Torben Kuhlmann. Post edited by dPICTUS.

Buy this picturebook

Einstein: The Fantastic Journey of a Mouse Through Space and Time

Torben Kuhlmann

NordSüd Verlag, Switzerland, 2020 NorthSouth Books, United States, 2022

When an inventive mouse misses the biggest cheese festival the world has ever seen, he’s determined to turn back the clock. But what is time, and can it be influenced? With the help of a mouse clockmaker, a lot of inventiveness, and the notes of a certain famous Swiss physicist he succeeds in travelling back in time. But when he misses his goal by eighty years, the only one who can help is an employee of the Swiss Patent Office, who turned our concept of space and time upside down.

German: NordSüd Verlag

English: NorthSouth Books

Chinese (Simplified): Ginkgo (Shanghai) Book Co. Ltd.

French: Editions Mijade

Japanese: Bronze Publishing

Catalan: Editorial Juventud

Korean: Booknbean Publishing

Greek: Psichogios Publications

Dutch: De Vier Windstreken

Persian: Houpaa Books

Romanian: Corint Books SRL

Russian: Polyandria Print LLC

Swedish: Lilla Piratförlaget

Spanish: Editorial Juventud

Czech: Dynastie s.r.o.

Buy this picturebook

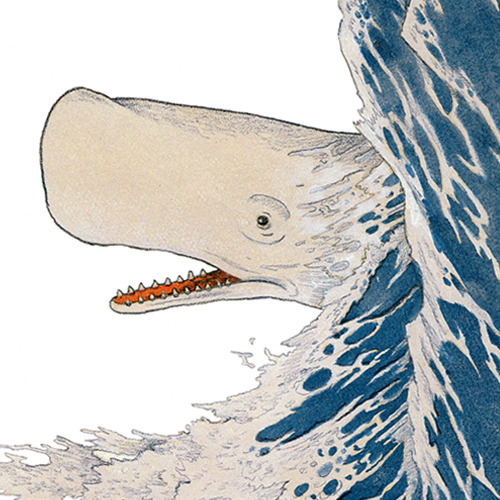

Edison: The Mystery of the Missing Mouse Treasure

Torben Kuhlmann

NordSüd Verlag, Switzerland, 2018 NorthSouth Books, United States, 2018

A long time ago, one mouse learned to fly, another landed on the moon... what will happen in the next Mouse adventure?

When two unlikely friends build a vessel capable of taking them to the bottom of the ocean find a missing treasure—the truth turns out to be far more amazing.

German: NordSüd Verlag

English: NorthSouth Books

Chinese (Simplified): New Buds Publishing House

Finnish: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava

French: Editions Mijade

Italian: Orecchio Acerbo

Japanese: Bronze Publishing

Catalan: Editorial Juventud

Korean: Booknbean Publishing

Greek: Psichogios Publications

Dutch: De Vier Windstreken

Persian: Houpaa Books

Romanian: Corint Books SRL

Russian: Polyandria Print LLC

Swedish: Lilla Piratförlaget

Slovenian: Desk d.o.o.

Spanish: Editorial Juventud

Czech: Dynastie s.r.o.

Buy this picturebook

Armstrong: The Adventurous Journey of a Mouse to the Moon

Torben Kuhlmann

NordSüd Verlag, Switzerland, 2016 NorthSouth Books, United States, 2016

Torben Kuhlmann’s stunning new book transports readers to the moon and beyond! On the heels of Lindbergh: The Tale of a Flying Mouse comes Armstrong: The Adventurous Journey of a Mouse to the Moon—where dreams are determined only by the size of your imagination and the biggest innovators are the smallest of all. The book ends with a brief non-fiction history of human space travel—from Galileo’s observations concerning the nature of the universe to man’s first steps on the moon.

German: NordSüd Verlag

English: NorthSouth Books

Chinese (Simplified): Ginkgo (Shanghai) Book Co. Ltd.

German-Arabic: Edition bi:libri

German-English: Edition bi:libri

German-French: Edition bi:libri

German-Italian: Edition bi:libri

German-Russian: Edition bi:libri

German-Spanish: Edition bi:libri

German-Turkish: Edition bi:libri

Finnish: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava

French: Editions Mijade

Italian: Orecchio Acerbo

Croatian: Planet Zoe d.o.o.

Greek: Psichogios Publications

Dutch: De Vier Windstreken

Persian: Houpaa Books

Polish: Wydawnictwo Tekturka

Romanian: Corint Books SRL

Russian: Polyandria Print LLC

Swedish: Lilla Piratförlaget

Slowenian: Desk d.o.o.

Language: Dynastie s.r.o.

Buy this picturebook

Lindbergh: The Tale of a Flying Mouse

Torben Kuhlmann

NordSüd Verlag, Switzerland, 2014 NorthSouth Books, United States, 2014

One small step for a mouse; one giant leap for aviation.

These are dark times... for a small mouse. A new invention—the mechanical mousetrap—has caused all the mice but one to flee to America, the land of the free. But with cats guarding the steamships, trans-Atlantic crossings are no longer safe. In the bleakest of places . . . the one remaining mouse has a brilliant idea. He must learn to fly!

German: NordSüd Verlag

English: NorthSouth Books

Armenian: Zangak Publishing

Chinese (Simplified): New Buds Publishing House

German-Arabic: Edition bi:libri

German-English: Edition bi:libri

German-French: Edition bi:libri

German-Italian: Edition bi:libri

German-Russian: Edition bi:libri

German-Spanish: Edition bi:libri

German-Turkish: Edition bi:libri

Estonian: Rahva Raamat

French: Editions Mijade

Hebrew: Agam Publishing House

Italian: Orecchio Acerbo

Japanese: Bronze Publishing

Korean: Booknbean Publishing

Mongolian: Amar-Urguu LLC

Greek: Psichogios Publications

Dutch: De Vier Windstreken

Persian: Houpaa Books

Polish: Wydawnictwo Tekturka

Russian: Polyandria Print LLC

Swedish: Lilla Piratförlaget

Slovenian: Desk d.o.o.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Johanna Schaible

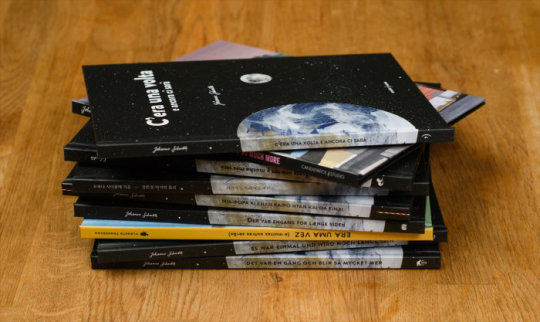

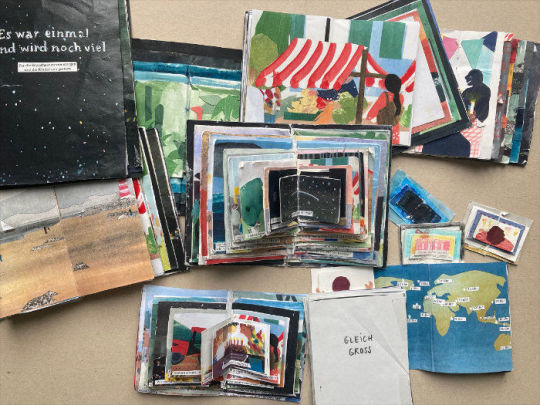

In this post, Johanna talks about her incredible debut picturebook ‘Once upon a time there was and will be so much more’. In the first dPICTUS Unpublished Picturebook Showcase in 2019, this project was voted for by 23 of the 30 publishers on the jury, acquired by Lilla Piratförlaget, and then published as a co-edition in nine languages.

Visit Johanna Schaible’s website

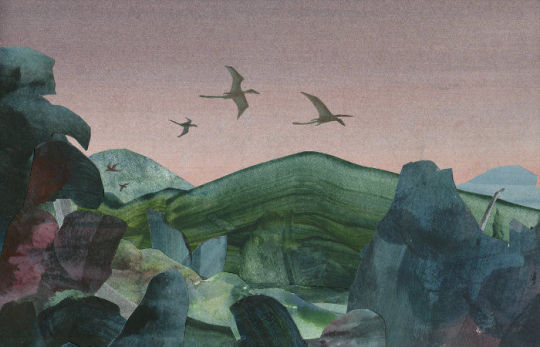

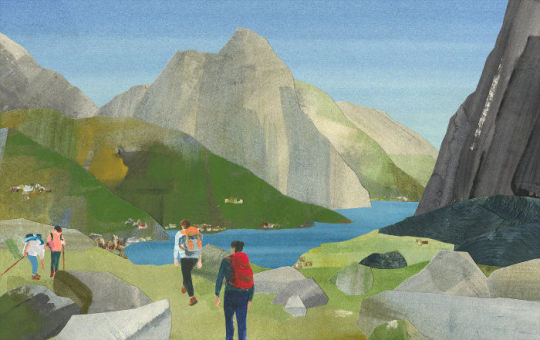

Johanna: I will tell you about my picturebook ‘Once upon a time there was and will be so much more’. It takes us on a journey through time. The book begins in the distant past, catches up to the present halfway through, and then leads us with questions into the future.

Millions of years ago, dinosaurs lived on Earth.

One hundred years ago, a journey took a long time.

A month ago, it was still autumnn.

What will the weekend bring?

Will you have children one day?

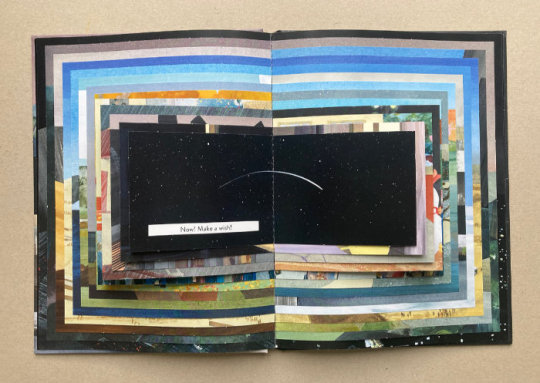

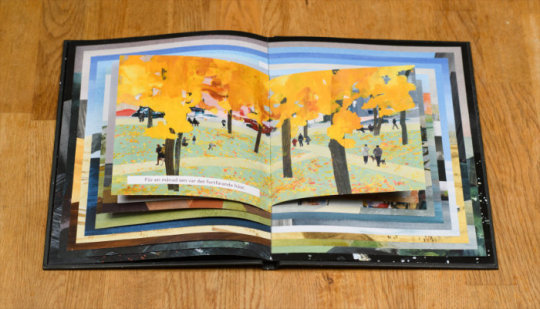

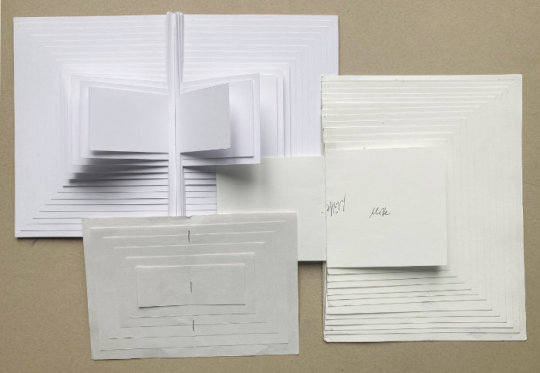

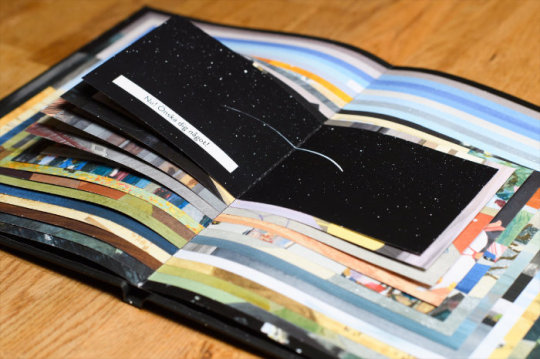

The time is depicted in a special way. If you open the book in the middle it looks like this:

The pages of the book become smaller as we draw closer to the present and grow larger again as we move into the future.

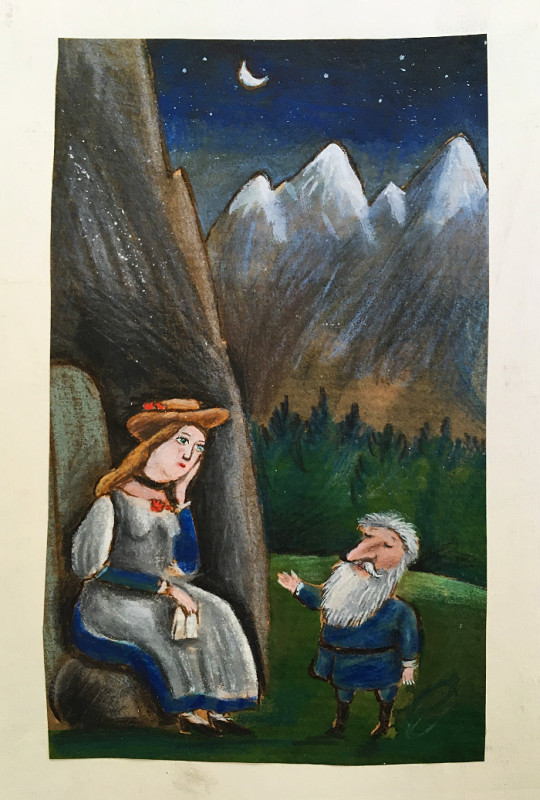

This is one of the first dummy books I made.

Back then, it was hard to believe that this would turn into a real book one day. For a long time, I heard from the publishing world that it is very difficult to produce a book like this and it would be even harder, if not impossible, to find a publisher who would take the risk, effort and cost to produce it. It took some time, but here it is!

The book’s journey started with Bolo Klub, which was founded several years ago by the Swiss illustration duo It’s Raining Elephants. Bolo Klub supports illustrators in completing a picturebook, and provides networking opportunities with professionals from the publishing world. I had the chance to take part in the first edition from 2018–2019. We were a wonderful group of fifteen illustrators that came together once a month to push our book projects forward, and to benefit from each other’s feedback.

Photograph by E.Ettlin.

I do a lot of projects moving between art and illustration. To make a picturebook sounded very challenging to me, especially because I rarely work on narrative.

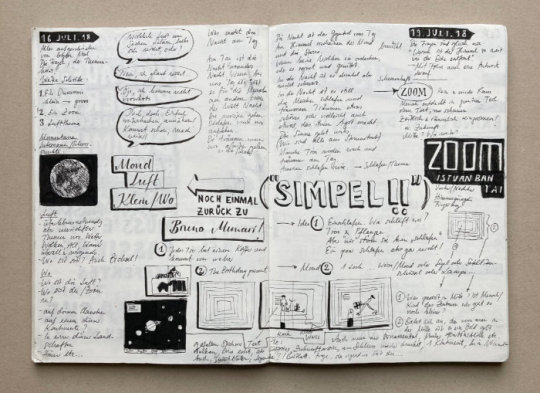

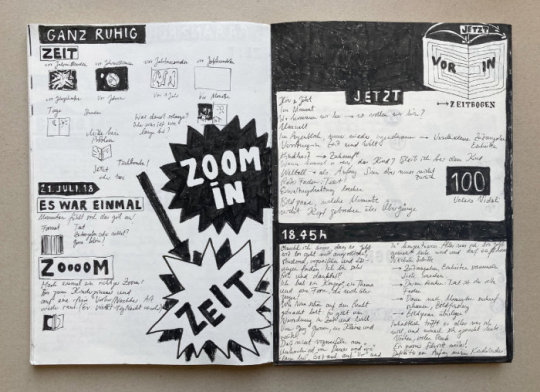

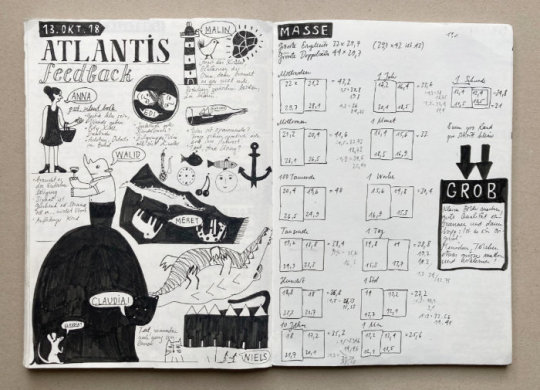

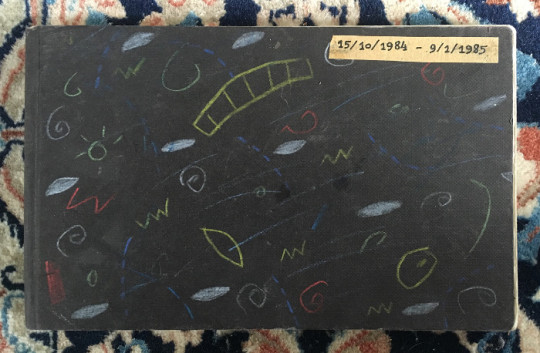

I always keep a logbook where I write about the project I‘m working on, including the inspiration and input I receive. This is the logbook from the meetings with the Bolo Klub.

From the beginning, I was attracted by books with exciting formats, and I wasn’t up for creating a regular one. I didn’t want a main character, and my starting points were thematically very open and global. My keywords, for example, were ‘night’, ‘air’ and ‘time’.

With the aim to really make progress on our projects, we spent a working weekend together. Besides the working, it was so enriching to exchange thoughts and ideas. In a creative process, we all face similar challenges.

Photograph by E.Ettlin.

I was working on two ideas: The first idea was a zoom, starting far away and coming in close to one child. The second idea was a dummy book with the topic ‘time’. Combining the two ideas was the turning point, and I had finally found the theme and concept I was looking for.

Photograph by E.Ettlin.

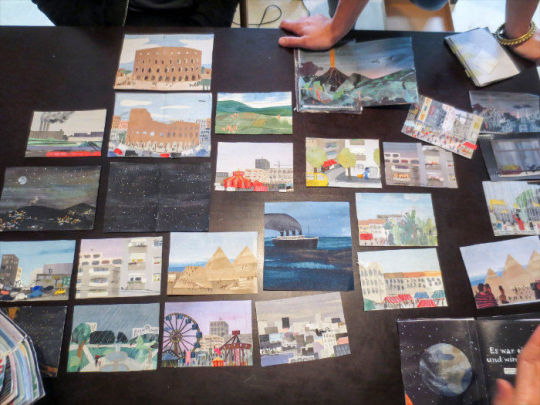

I often work with collage and painting for my illustrations. I also do my sketches using this technique because I want to see the atmosphere of an image and idea straight away.

To start with, I made some little sketches the size of postcards. In this case I work more roughly, and I appreciate the liveliness that inhabits these sketches. I feel comfortable working quite fast. It helps me to develop the images intuitively.

Photograph by E.Ettlin.

I made a lot of little dummy books to observe what happened while turning the pages. I had to find simple sentences that gave the timeline and structure to the book.

Alongside the development of a coherent journey through time, I had to think about the feasibility of my idea. When I did my little dummy books, they were very imprecise. It was only when I started to measure the pages and make examples of the real book size that I realised that my pages didn’t just get smaller, but their format changed completely.

This became one of the most important pages for me in the logbook: the one with the measurements of each image.

The format changes from a more common picturebook size...

... to a wide panorama format, and then back again.

To be sure about the size, it helped me to use frames that I put over my collages, to be able to change and move elements until the end.

With the Bolo Klub and my dummy book, I travelled to the Bologna Children’s Book Fair 2019.

Photograph by E.Ettlin.

In Bologna, some publishers told me they were interested. But I never heard from them again. One publisher seemed particularly interested, but didn’t propose me a contract at that time.

It was another call that boosted this project. I sent my dummy book to the first edition of the dPICTUS Unpublished Picturebook Showcase in 2019, and was thrilled when I heard that 23 of the 30 publishers on the jury voted independently for my project. It made me very happy because it showed me that, even if that didn’t mean that they would publish it, my book was touching them in some way.

Frankfurt Book Fair 2019 photographs by Theodore Bauthier (@b.c.theodore).

It was also through The Unpublished Picturebook Showcase that my book project found the publisher that accepted the big challenge of making it a reality. I was very lucky with my Swedish editor Erik Titusson from Lilla Piratförlaget, and Sam McCullen from dPICTUS / Picturebook Makers on the graphic design. In our collaboration, I felt a big trust in me and my work.

My creative process for this project was similar to how it very often is for me: Some pictures came easily and stayed very close to the original sketch...

But for some of the other pictures, I had to do them over and over again until they felt right to me.

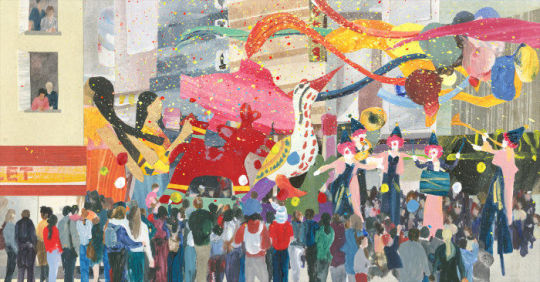

With my technique of mixing painting and cutouts, I really like to develop sceneries and creating atmospheres. To show humans inhabiting these scenes was a challenge in the beginning. It became easier after I decided to paint the figures at a larger size. For some images I made the whole setting first. Then I cut out the figures and inserted them digitally.

Whenever I got stuck, it helped to go outside and take photos of the daily life around me.

This, for example, is a house in the old part of Bern, which inspired me for the following image.

To make this book was a precious experience to me. The companionship and support from the Bolo Klub was very helpful and enriching. On this journey, I’ve had the chance to meet a lot of inspiring people who shared their knowledge and offered me their help. I‘m so thankful to all of them, and especially to my closest allies and friends who support me in all of my projects.

I hope that this book will offer to people of all ages the possibility to talk about what kind of future we imagine and want to build together.

Illustrations © Johanna Schaible. Post edited by dPICTUS.

Buy this picturebook

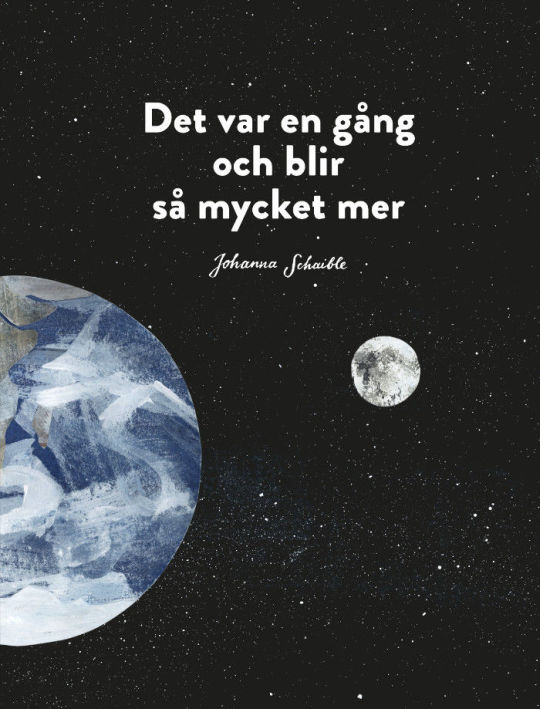

Det var en gång och blir så mycket mer / Once upon a time there was and will be so much more

Johanna Schaible

Lilla Piratförlaget, Sweden, 2021

Billions of years ago, land took shape. Hundreds of thousands of years ago, people built some very large things. A month ago, it was still autumn. Where will you be in an hour? How will you celebrate your birthday next year? What will impress you forever? What do you wish for the future?

This book takes us on a journey through time. It begins in the distant past, catches up to the present halfway through, and then leads us with its questions into the future. Both the fleeting present and the enormity of time are depicted in a truly unique way: the pages of the book become smaller as we draw closer to the present, only to grow larger again as we move into the future.

Swedish: Lilla Piratförlaget

English: Candlewick Press (late 2021)

Italian: Orecchio Acerbo

German: Carl Hanser Verlag

Portuguese: Planeta Tangerina

Spanish: Leetra (Mexico)

Danish: Turbine

Greek: Martis

Korean: LOGpress

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harriet van Reek

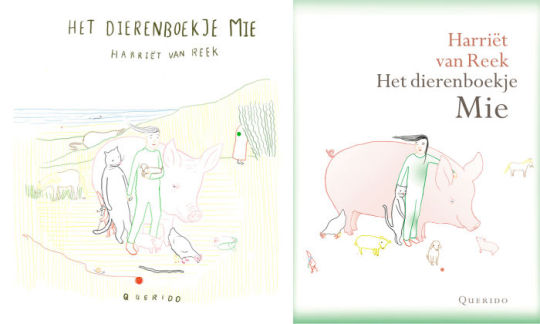

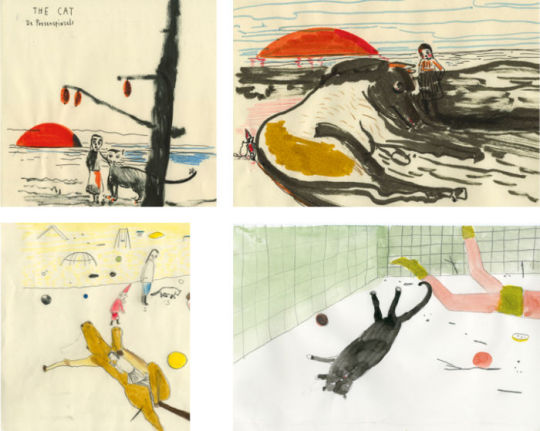

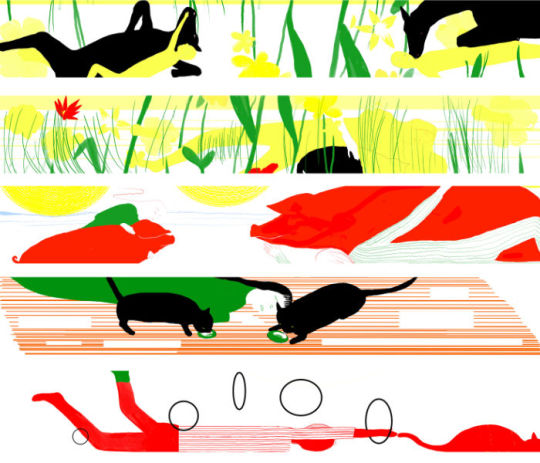

In this post, Harriet talks about several of her books, including her latest publication ‘Het dierenboekje Mie’ (The animal booklet Mie), and her stunning picturebooks which focus on letters and handwriting. She also shares fascinating insights into her creation process.

Visit Harriet van Reek’s website

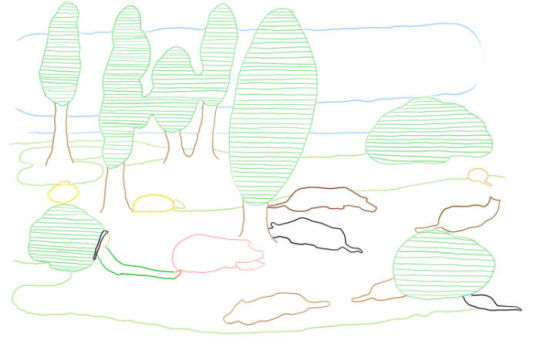

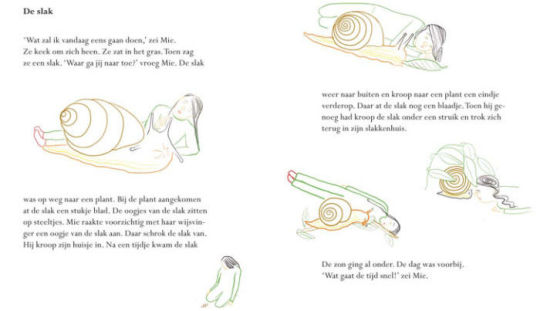

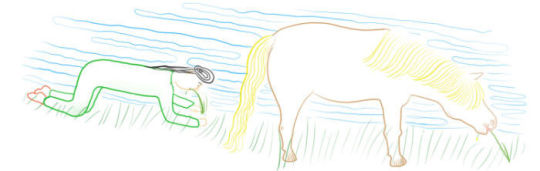

Harriet: Let me tell you something about the book that I just handed in to the publishing house Querido: ‘Het dierenboekje Mie’ (The animal booklet Mie). It’s a gentle book; there’s a lot of lazing around. A bit of lying down, a bit of stroking, licking, and caressing. Nothing special. It’s like a counter-reaction to the rush and constant requirements. I wanted to draw attention to the senses and the adventure of touching, feeling, hearing, and looking closely. Presenting ordinary things in a different way, allowing you to actually see them again, with a surprised look.

I had also been looking for a more ecocentric approach, based on empathy and respect for animals and nature.

Before I knew exactly where I wanted to be, in language and image, I went on a search. It’s kind of like peeling until you get to the pit. It started with two different leporellos, the first of which I got rid of because I thought it was all nonsense, and the second I got rid of because I thought it was too boring, too romantic, too soft.

During the first lockdown, in April 2020, I found the right approach. I first wrote the text and then drew the book on a drawing tablet, a Cintiq. I had never done that before. Until that point, I worked on paper, with watercolour, coloured pencil, a drawing pen, and ink.

The most difficult thing for me is to be free. To find freedom. Finding openings to the imagination, to language. The wheel has to be reinvented over and over again. This also makes creating a new book challenging. It’s like a complicated game, having to find the secret rules of the game to solve the riddle.

The idea must be good and the text must be good. The subject of the book must have a certain urgency and meaning. So it’s always a matter of waiting for something like this to arise. I don’t want to just make something up.

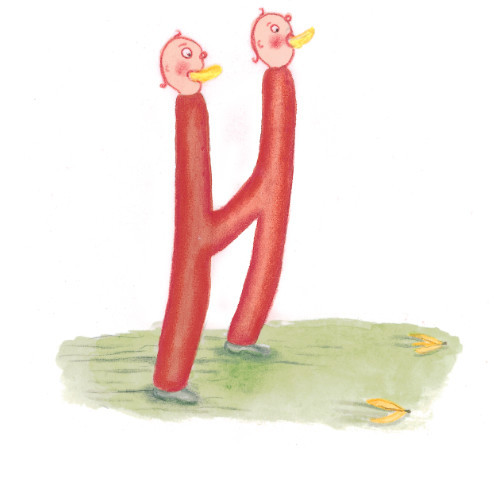

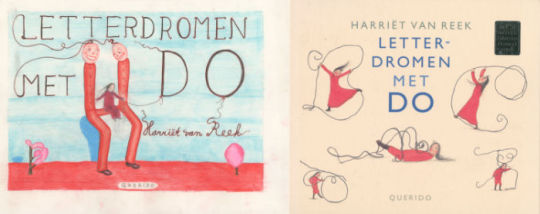

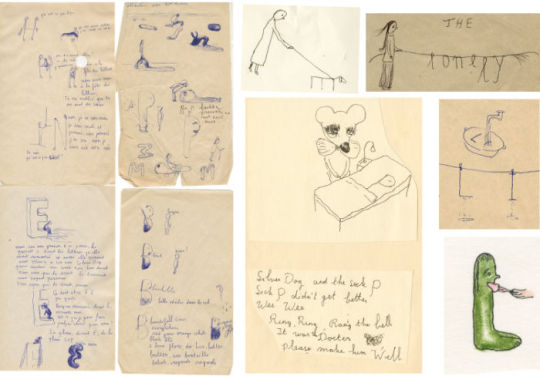

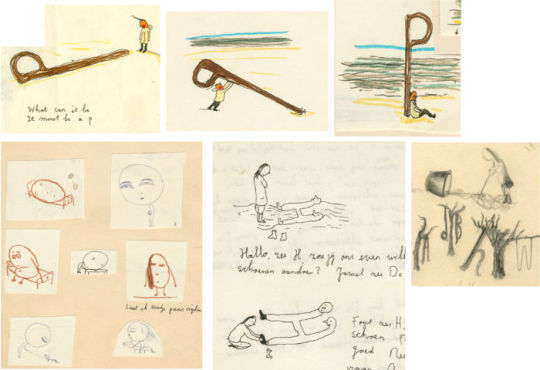

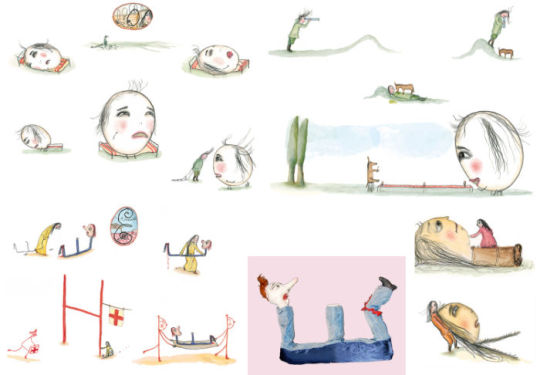

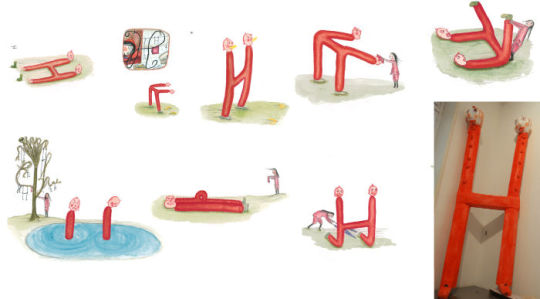

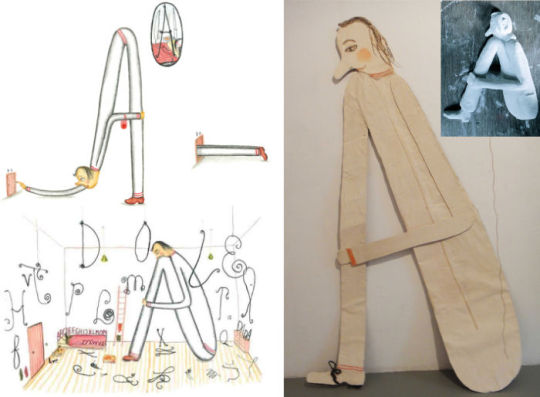

Another topic I’ve worked on before is letters and handwriting. Handwriting seems to be lost in our keyboard society. I created two books on this subject. First, there was ‘Letterdromen met Do’ (Letterdreams with Do). I turned the letters into living beings. They come to life by themselves, if you write by hand.

The letters challenge you to create stories with them, simply because of their shape. This way, I hoped to lure the reader towards the letter and to be carried away by it myself as well.

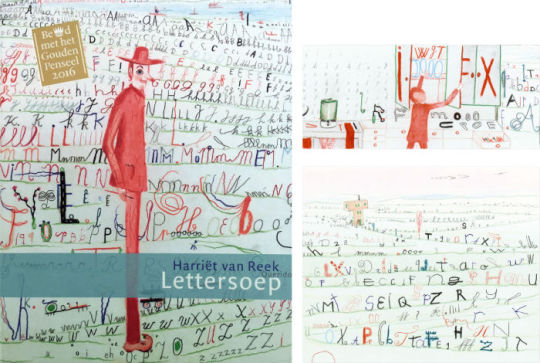

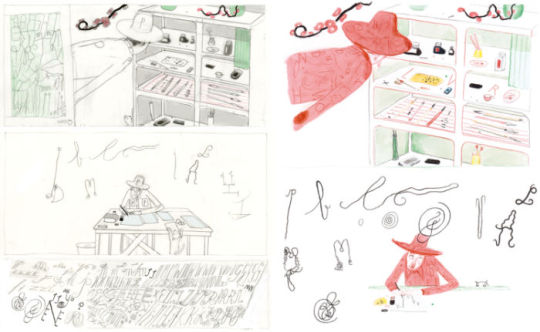

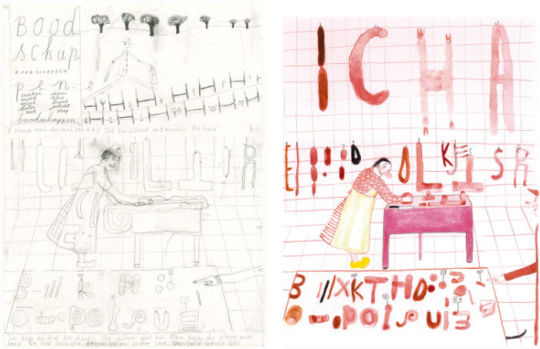

After Letterdreams with Do, I made another book about letters. This time, there was a strong emphasis on writing and the personal expression which is possible through handwriting: ‘Lettersoep’ (Letter Soup).

The main character is an L, he lives in a T, together with a P, a cat. There are all kinds of puns in the text and the images, which makes the book, just like ‘Letter Dreams with Do’, difficult or perhaps impossible to translate. The book also covers various professions that are either dying out or are a craft.

I actually like the sketches more than the final work. I often think, “why did I go this far, I was already there.”

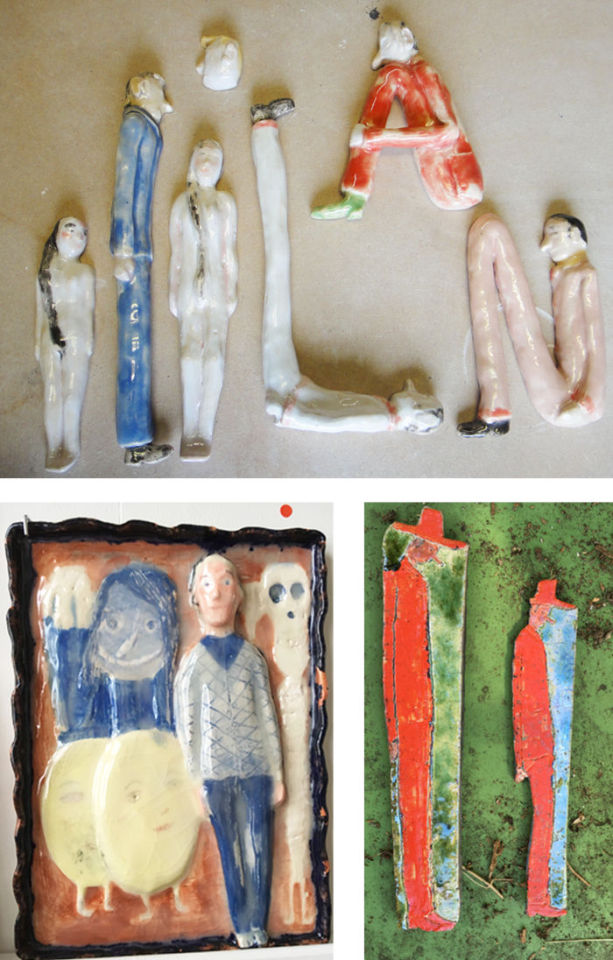

It usually takes several years between one book and the other. In the meantime, I do other things. I sometimes spend my time creating ceramics, freehand drawing, or weaving.

Along with Geerten Ten Bosch, I create visual theatre and performance. In this photo, we’re performing actions on a few spectators. The aim of our work is always to stimulate the viewer’s imagination in an associative way.

We also created an experimental picturebook together.

‘Ei! Ei!’ (Egg! Egg!) was made by cutting out drawings and merging them into new images through collage. It’s very nice to alternate solitary work with working on projects together.

I like antique Japanese ghost stories drawn on book scrolls, the Yokai-ga, Jockum Nordström’s ‘children’s’ picturebooks about Sailor and Pekka, and I love 19th century picturebooks.

Furthermore, I wish the studio Fotokino in Marseille was located in Rotterdam, my home town, because of the exhibitions and the attention they have for illustration and art.

Walking along coasts and through fields helps me to think about a book, and I am always looking for a place where I can work in peace for a few months, somewhere outside, far from the hectic city. (If you know any places, I’d love to hear about them.)

I hope I was able to inspire you with my contribution and thanks for reading!

Illustrations © Harriet van Reek. Post translated by Gengo and edited by dPICTUS.

Buy this picturebook

Het dierenboekje Mie / The animal booklet Mie

Harriet van Reek

Querido, Netherlands, 2021

Sixteen stories about Mie, a girl who spends every day with the animals. She takes the cow to the sea, or she keeps an eye on the hen, which has just given birth to chicks. She tickles the pig, brushes the cow, and pets the cat while it is raining outside. When the pony does pony things, Mie tries to imitate it all. And at the end of such a tiring day, Mie falls asleep in the grass.

A disarmingly simple and soft picturebook to calm you down, completely.

Buy this picturebook

Letterdromen met Do / Letterdreams with Do

Harriet van Reek

Querido, Netherlands, 2008

Do is busy making letters all day long. She gets so into it that the letters come to life for her. In her dreams, Do even experiences the most fantastic adventures with them! A picturebook for children who are starting to discover letters themselves, but also for anyone who likes letter adventures.

Buy this picturebook

Lettersoep / Letter Soup

Harriet van Reek

Querido, Netherlands, 2015

I’m going to make nothing of anything. I’m going to make a BIKE out of NOTHING, says Letterel. How are you going to do that? Lettercat asks. Very simple, says Letterel. Cut the N into three pieces and lay it out a little differently, and if I cut ANYTHING into 6 long sticks, 4 short and two curves, I can make a lot more. Letterel lives with a Letter cat in a letter house. He loves letters. Cut letters, look at letters, dream letters, and write letters! He conjures a beautiful colourful world where the imagination has no limits.

Buy this picturebook

Ei! Ei! / Egg! Egg!

Harriet van Reek & Geerten Ten Bosch

Uitgeverij Philip Elchers, Netherlands, 2018

An experimental picturebook by Harriet van Reek and Geerten Ten Bosch. Together they present a crazy and far from traditionally designed story about two eggs and a puppet show. A book about friendship and courage, a feast for the eyes and the heart, in which you are challenged to read and look carefully.

0 notes

Text

Marika Maijala

In this post, Marika talks about ‘Ruusun matka’ (Rosie’s Journey), her wonderfully fresh debut picturebook as an author and illustrator, published in Finland by Etana Editions. She talks openly about her intimate creation process, and the challenges of writing.

Visit Marika Maijala’s website

Marika: When writing this blog post, I am completely stuck in my writing process. I am trying to write a new story, but it keeps escaping me. Actually, even this blog post makes me a bit nervous, because it is a story as well: How did the book turn out the way it did?

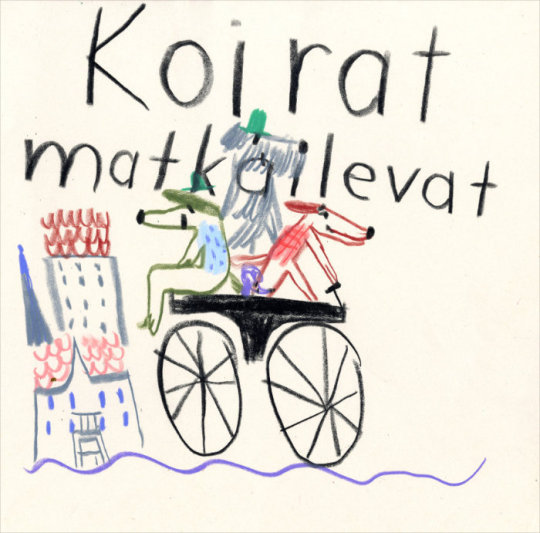

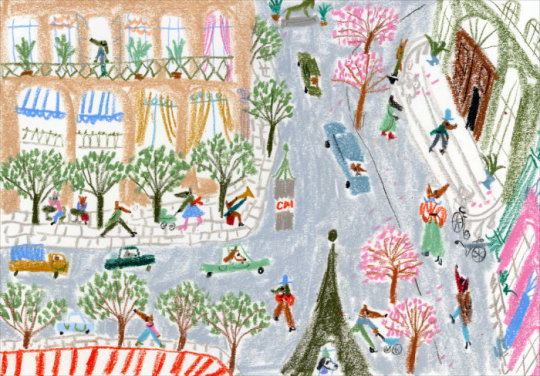

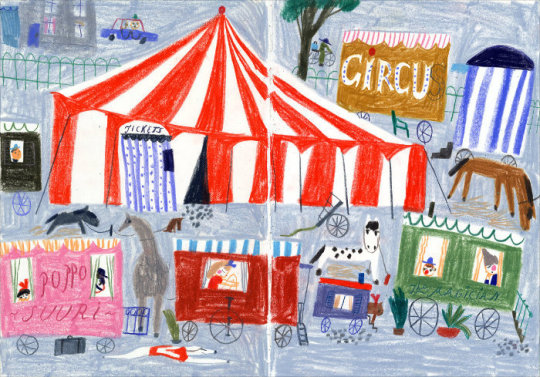

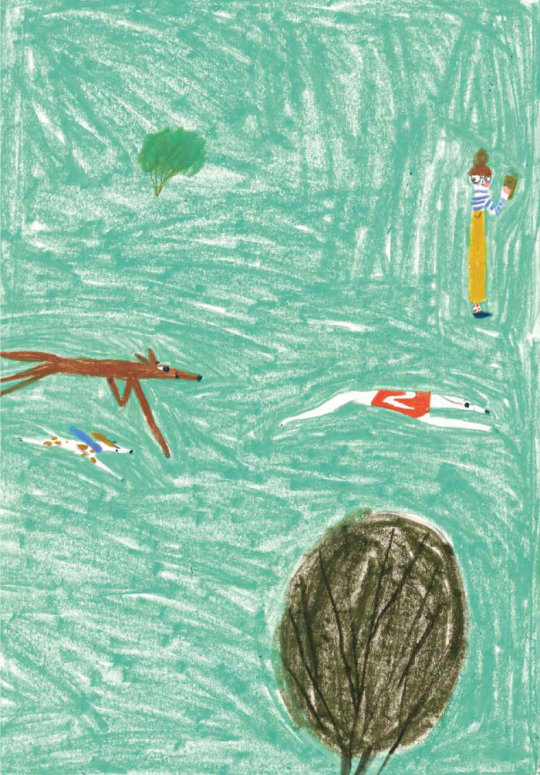

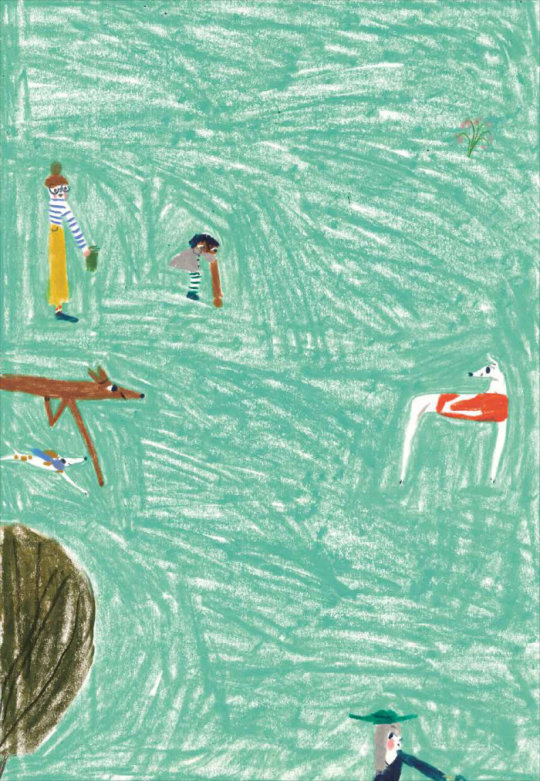

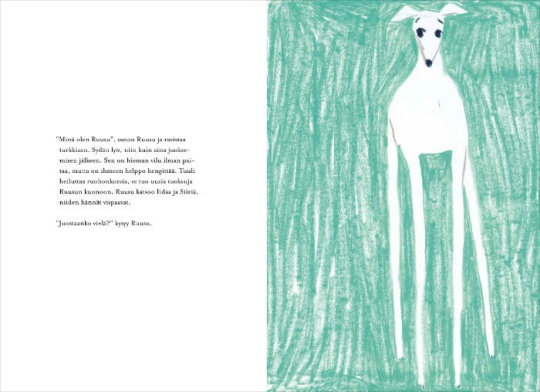

Rosie and the race dogs in ‘Rosie’s Journey’ (Etana Editions, 2018)

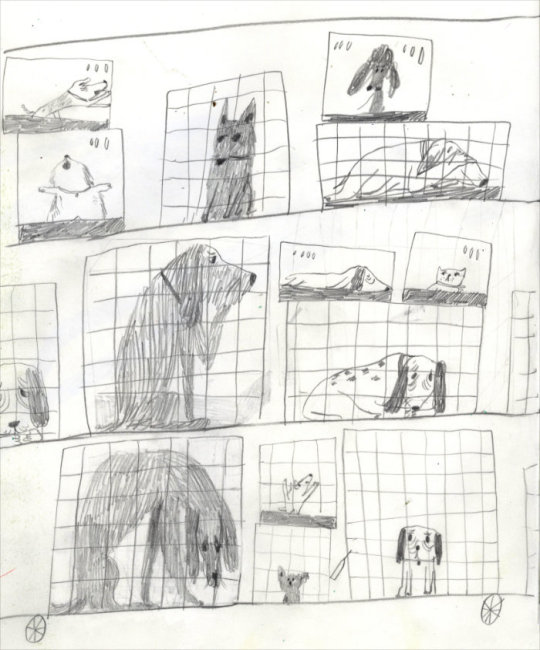

My first picturebook as an author was ‘Rosie’s Journey’. It’s the story of a race dog, who runs away from the race track to find a place where she can run the way she likes to. Now, as I am struggling with my writing, I have returned to this project often and tried to figure out how I did it. It is hard to reach, as now, looking at it after a couple years have gone by, I only remember chaos, randomness and doubt, exactly the same feelings I am having now. I think I need to go further back to see how it started.

I remember sitting in a book meeting in a publisher’s office a few years back. We were discussing a forthcoming book project. There were two stories on the table, and the publisher asked which would I rather illustrate, this other story, or this one, with two happy dogs? I remember replying immediately: “the one with happy dogs”. The other story got selected, and it turned out to be a great book, but I think that deep inside of me I only want to draw happy dogs. In the end I even made a very stupid story for myself about four dogs driving around in their car. They are happy.

So maybe that’s why the main character in my first authored book is a dog. She just appeared in my sketchbook one day. Here is the first sight of Rosie. She seems happy.

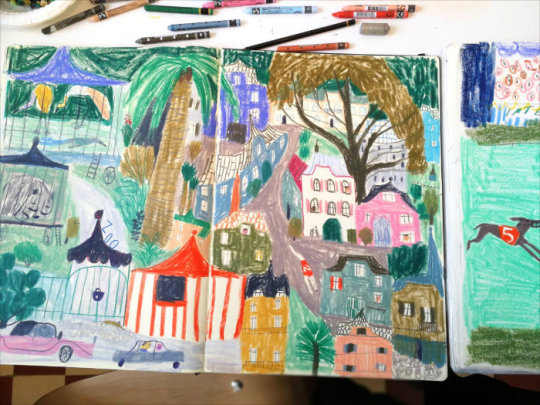

This was a new notebook – an A3 Moleskine I had bought on one Interrail trip in Italy, and I carried it all the way home through Europe; how stupid. Especially as it was still empty after two years. That was a time when I was very tired of my work. I had illustrated children’s books for over a decade, worked with wonderful writers and received nice reviews for my illustrations. But I felt I didn’t really enjoy drawing. I used computer a lot, because I didn’t trust my drawing skills. So I took out this huge notebook and started scribbling, messing around. Drawing badly. Pictures came out. They were bad, but I enjoyed making them.

Around that time, I was selected for a masterclass with some other Finnish illustrators. Our teacher was Kitty Crowther, whom we all admired very much, so this was a special weekend for all of us. January was cold that year in Helsinki, and the course took place in a spooky old house by the sea. We were running on the frozen sea and making all kinds of exercises to free our creation and find our inner stories.

That weekend, I showed my new drawings for the first time to other people and got encouraged by the feedback I received from Kitty and other illustrators. Maybe I really was going in the right direction? We still often talk about this weekend with those artists, and looking back at it now, I think it was an important turning point for many of us. For me it was.

This is one of the drawings I did on the course. I still look at it when I am having a bad day, or I feel lost. Depending on the day, I am either the lion or that person getting eaten by the lion.

More drawings of Rosie started to appear in my notebook. I dared to show them to my publishers Jenni Erkintalo and Réka Király at Etana Editions. They were also encouraging and said that there was a story building up. I think it has always been difficult for me to see value in my work and ideas; this is why having friends and colleagues whom I can trust has been so important. When I doubt, they say just go ahead. I try to do the same for them. Through this whole process I was not alone, and so many decisions concerning the images and the story we made together with Jenni, Réka as well as the editor Kirsikka Myllyrinne, who encouraged me to keep the story very simple.

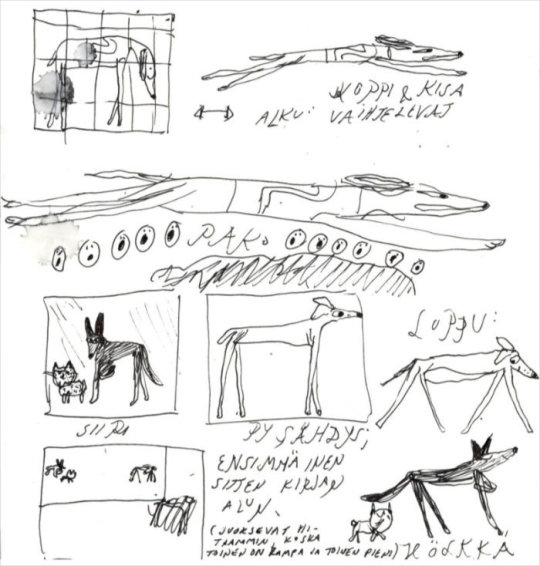

Here we get to the point where I always struggle: the story. When I was forced, I was able to produce this synopsis for the book:

The story goes: First, Rosie runs at the stadium, then she runs to escape the stadium, and in the end, she runs with friends because she wants to. And at the turning point, she stops. How did this scribble grow into a picturebook with 25 spreads (normally the picturebooks I illustrate have about 12 spreads)?

I think this book grew out of drawing – the joy of drawing. In a way, this is the content of the story as well, to find your own way of being, your own expression. For Rosie it is running, maybe for me it is drawing. And when I found the enjoyment in drawing, I got enough courage to finally write the words too, which so often escape me.

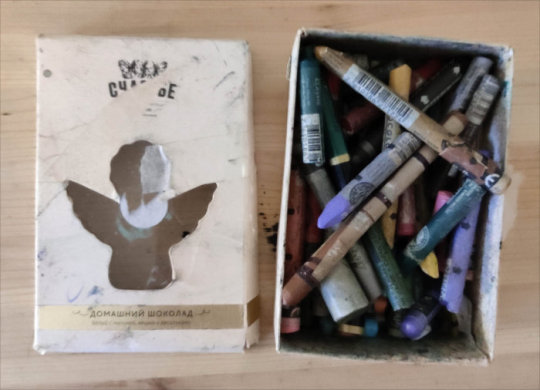

And maybe, in the end, it was just about finding the right tools for drawing. I remember an exercise from Kitty’s course, in which we were drawing, eyes closed, only feeling the paper, and the pen touching the paper. I really love how the crayon feels

on this particular type of paper. And funnily enough, to approach a visual task through some other sense than vision, helped me to create an image I felt was also interesting to look at.

Drawing in these notebooks was a very physical act: I filled five of them, drawing dozens and dozens of pictures. Also, scanning the images from these books required some patience as they are large, heavy and annoying to handle.

One of my crayon boxes is an old Russian box of chocolates given to me by Finnish writer Hannu Mäkelä. We have made many books together. He is also the creator of my favourite books from childhood: the ‘Herra Huu’ (Mr. Boo) series.

It is quite an exhausting method to search for the story through drawing. I guess I sort of needed to live the story myself, to know how it goes. There are a large amount of drawings that did not end up in the final book. But I think I still needed to draw them.

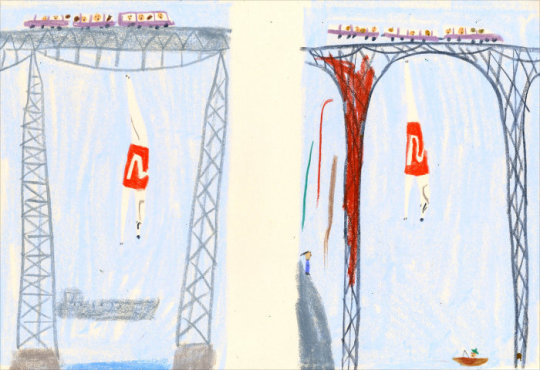

Life on and under the bridge in a sketch for ‘Rosie’s Journey’. Unpublished.

Rosie makes a leap. Unpublished.

I don’t like to put morals in my stories, because who am I to teach anyone. I would rather let people find their own meanings in the story. Maybe I am more trying to find out about things myself, I have questions in mind, not answers. And some questions get answers during the process, some don’t.

Maybe the questions in this story were: What is it to be happy? What is it to be free? What is keeping us from doing things we love? Why do we hurt, imprison and enslave each other: humans, animals? Can I do something? If I save myself, what happens to the others? What can be discussed in a children’s book?

In the story, I combined my own history and happenings during the past few years with the story of a real rescue dog, Rosie. My friend saved her from a bad place and took her to her home, where she lived peacefully with three other dogs. She was a hound dog, just like Rosie in the book, the most elegant creature I have ever seen. I thought that maybe through my experiences I was able to understand her, that there are feelings, desires, experiences, all living creatures share.

An early sketch for ‘Rosie’s Journey’.

Race depot in ‘Rosie’s Journey’.

This I try to keep in mind when I draw and write children’s books: we share so many things, even with those we think we don’t share anything with at all. In a way I want to stress that, as much as we are and will always be focused on our own little lives, and the ups and downs in them, there are millions of others doing the same thing. And these ups and downs are very precious for those experiencing them. Kindness I also like a lot.

A sketch from my Italy notebook.

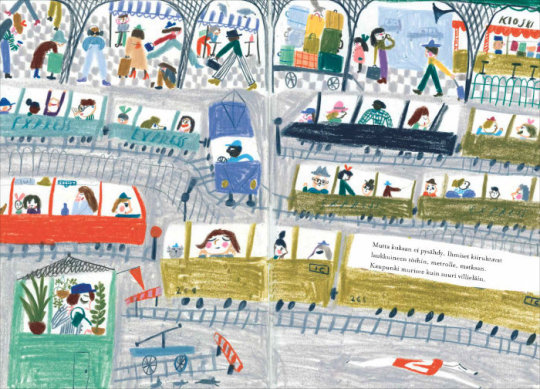

I love to watch people and animals doing their things. At the stations, in malls and supermarkets. On the streets and in the parks.

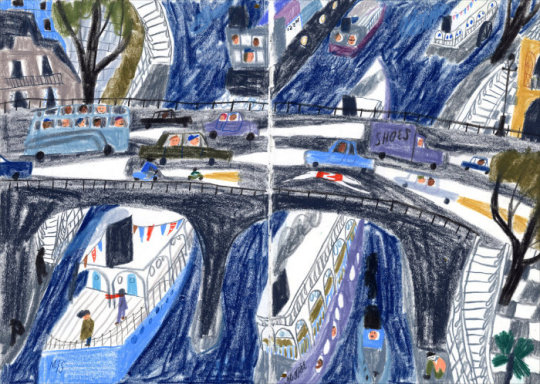

The train station in ‘Rosie’s Journey’.

I love to draw so many details in my illustrations that they often almost steal the story. Or they become the story, which actually I don’t mind. Something I really was fighting against in Rosie’s story as well was its linearity, the basic narrative structure it follows. Maybe I was trying to show options of where the story could go. Or that in a way our stories depend on other stories.

Spring in the city from my second authored picturebook ‘Suden hetki’ (Etana Editions, 2020).

People and animals living their lives in ‘Joulu juksaa’ (Etana Editions, 2019), a Christmas story written by Juha Virta and illustrated by me.

For many of the ‘best’ pictures (in my opinion) in ‘Rosie’s Journey’ I don’t have different/alternate versions. The pictures came out in one moment, with no effort, no planning, no pain. I didn’t want to redraw them; they had everything I wanted in them. In a way, I had made it easy for myself, as the concept of the book is so clear: Rosie is just running through different sceneries and settings; all I needed to do was to draw them. The themes – freedom vs imprisonment – I had in my mind and they can be found in the pictures when you study them.

I said that creating the story was a challenge for me. Still, I guess I know what I like in a story. I wanted it to be a simple story. And I didn’t want there to be any big climax in the end. Rosie just finds two friends and they run together. As simply as it sometimes goes in life. But we made a little change in the way of telling things, when the dogs start to run together. Until this point, Rosie has been running alone through large panoramic scenes, in an undefined time. In this important moment, when the dogs find each other, the story time is slowed down, and cut into a sequence of images, like in a film.

Rosie, Siiri and Iida in ‘Rosie’s Journey’.

In a way ‘Rosie’s Journey’ is a classical coming-of-age story, which pictures the growth of a protagonist to selfhood. I think the story became clear to me only when I made the last image. And it really is the last one in the book (although of this portrait there are at least five different versions). Also, the text on the last page was the last thing I wrote in the book. It came after long discussions with many friends, having gone through some small hardships in life, having tried terribly hard to find the right words, and then they came, immediately when I stopped trying:‘I am Rosie’, says Rosie. — ‘Shall we run again?’

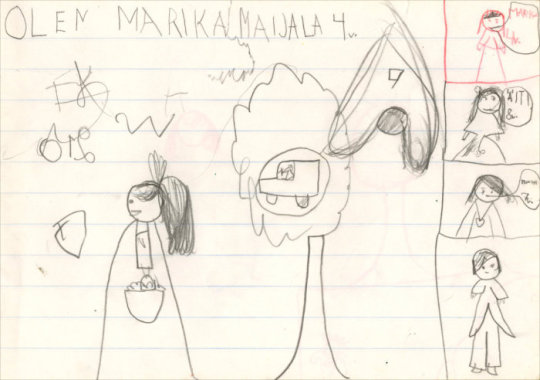

There are so many ways we can express ourselves, and no way is above or below. I guess it depends on each of us which we find most important, or dear, easy or hard. I noticed that for me, when making this book, it was important to utter words as well. At first, we had thought with the publishers that it would be a book without words. But to dare to use words, and to use my own words, felt very important to me. Maybe for me, an essential way to express my thoughts and feelings about this life is to combine words and images. A long time after finishing the book, I found this drawing in my childhood home.

“I am Marika Maijala. I am 4 years old, my sister is 7 years, and my mum 8 years.”

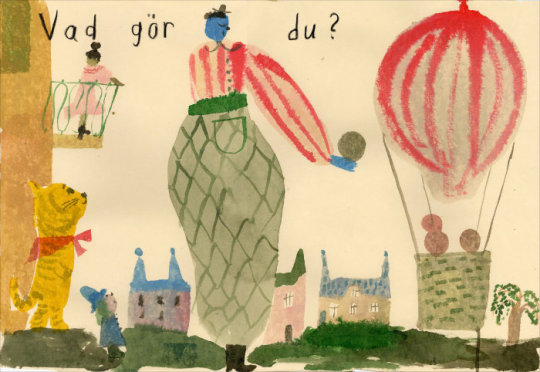

I tried to draw a picture of my writer’s block. I am the tall creature piling heavy stones into the hot air balloon. A little girl asks, “What are you doing?”. I am making an easy thing difficult. Instead of just letting the balloon fly, I fill it with stones. Or, maybe I am making the impossible: I’m going to fly with a balloon that really cannot fly. I guess I can choose.

Illustrations © Marika Maijala. Post edited by dPICTUS.

Buy this picturebook

Ruusun matka / Rosie’s Journey

Marika Maijala

Etana Editions, Finland, 2018

Rosie is a race dog. By day she runs at the track. By night she sits in her little room. One day she doesn’t stop at the end of the track. She jumps over the fence and runs away. Rosie keeps running. Where does she go? A sensitive portrayal of a special journey by award-winning illustrator Marika Maijala. This large-format book is Marika Maijala’s debut picturebook as both author and illustrator.

Finnish: Etana Editions

Swedish: Förlaget

French: Hélium

Spanish: SM

Italian: Clichy

Korean: Munhakdongne

Chinese (Simplified): Gingko/Post Wave

Chinese (Traditional): Pace Books

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

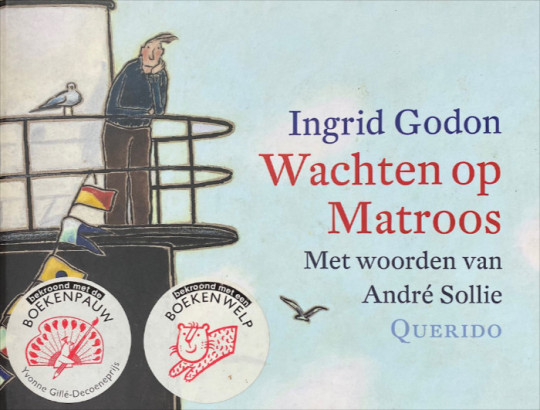

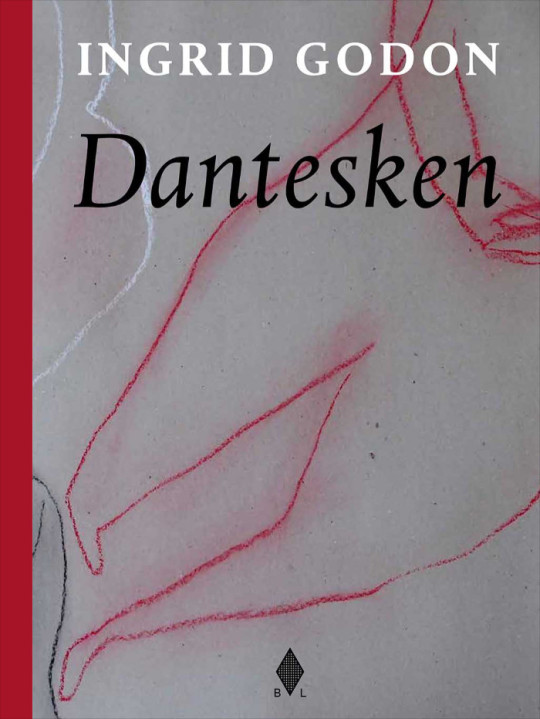

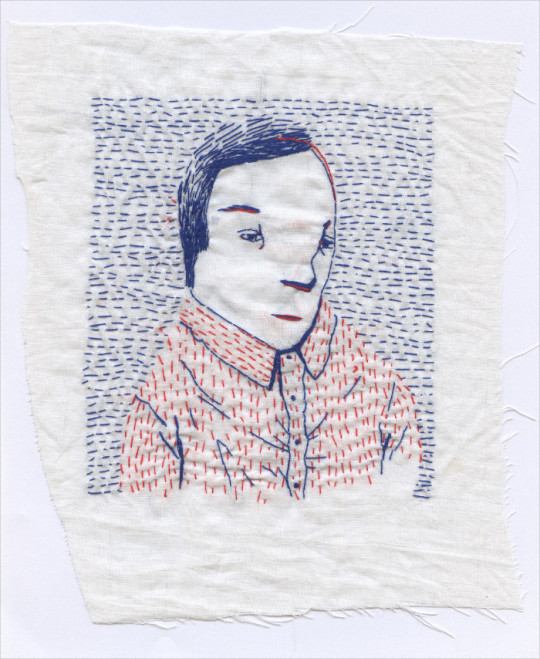

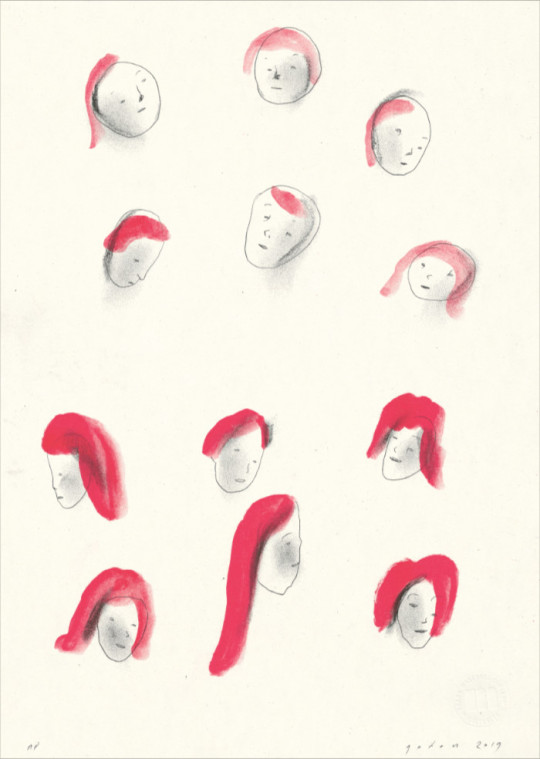

Ingrid Godon

In this post, Ingrid talks about her working process, and she shares stunning illustrations from some of her books, including the ‘Ik Wou’ trilogy with words by Toon Tellegen, and ‘Dantesken’ which features over 600 pages of autonomous drawings. She also shares wonderful fabric sculptures, ceramics and textile art.

Visit Ingrid Godon’s website

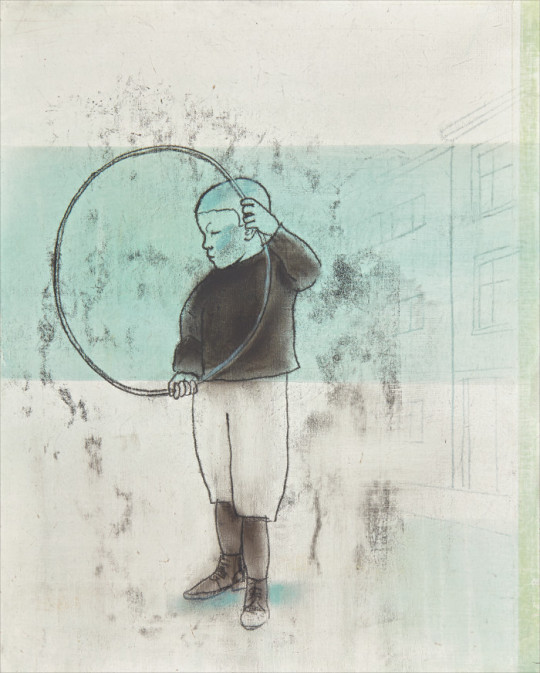

Ingrid: When I was a child, I was always watching. From a distance. Who did what, and how they did it. I drew. Not what I saw, although I did store the images in my mind. One day, they would come out. Drawn. School didn’t work out, but I kept drawing. I met Rik Van den Brande, an illustrator and teacher, at the academy. He took me under his wing and I kept drawing. I soon got assignments as an illustrator. I was working! Drawing became my work.

Educational publishers gave me assignments. This led to the creation of ‘Nellie & Cezar’ in 1995, which, via an educational detour, turned into a short book which remains popular with toddlers and teachers to this day. It became a success in many versions, animated movies were made from it, and Nellie & Cezar became great puppets. And I kept drawing, especially for children.

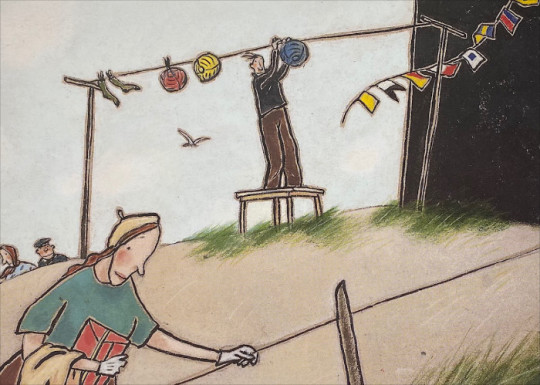

I made ‘Waiting for Sailor’ in 2000, and took the initiative for a story of my own for the first time. My dear colleague André Sollie wrote my story and I drew. That was the start of an international story. The book won many awards, and was published in English, French, German and Korean.

Foreign publishers were now asking me to make books for them as well. Often the German, French, Swedish or English books were never even published in Dutch. I received more awards, and in 2020 I was longlisted for the ALMA for the fourth time.

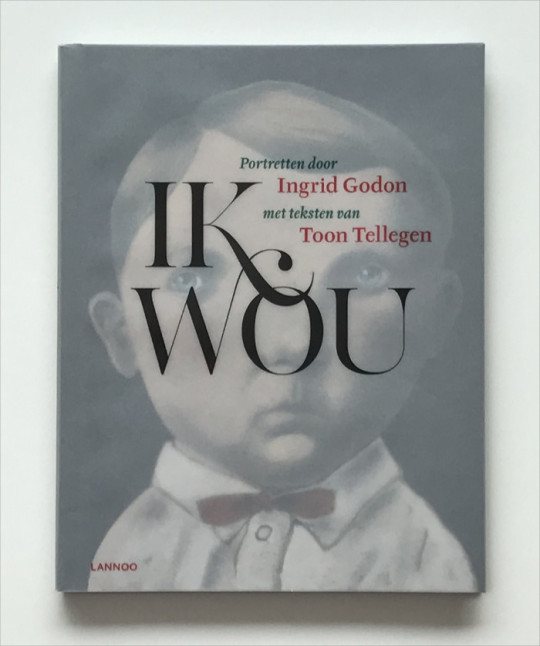

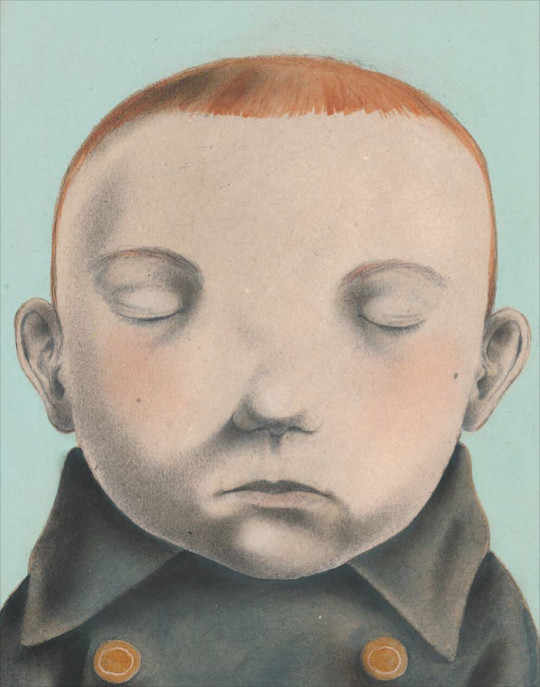

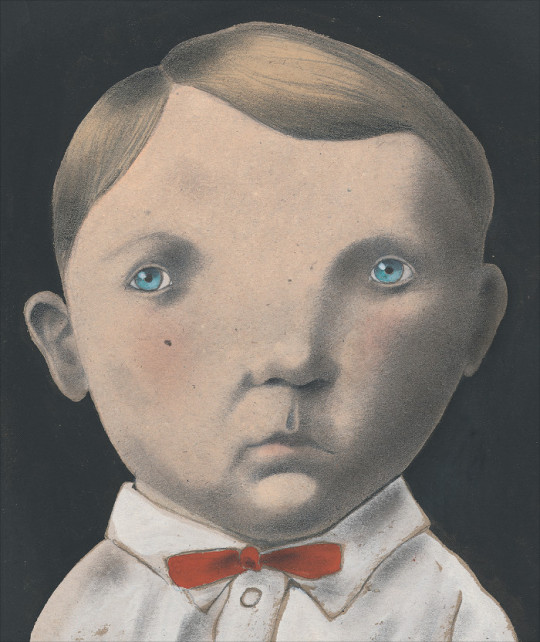

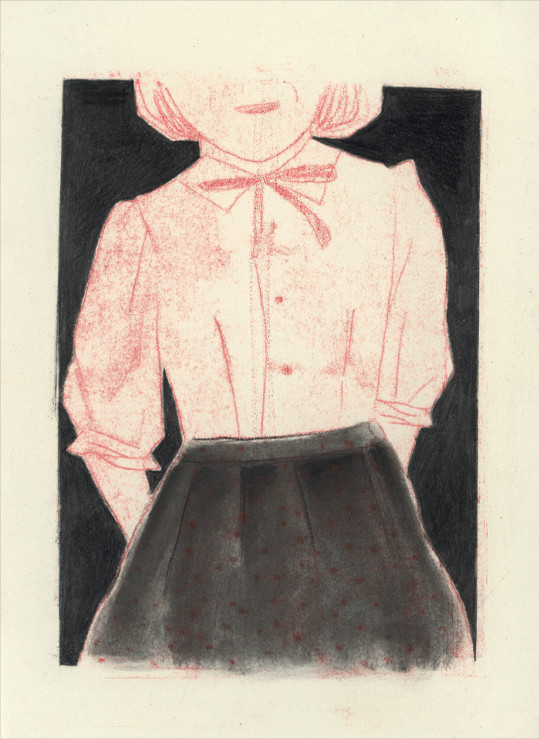

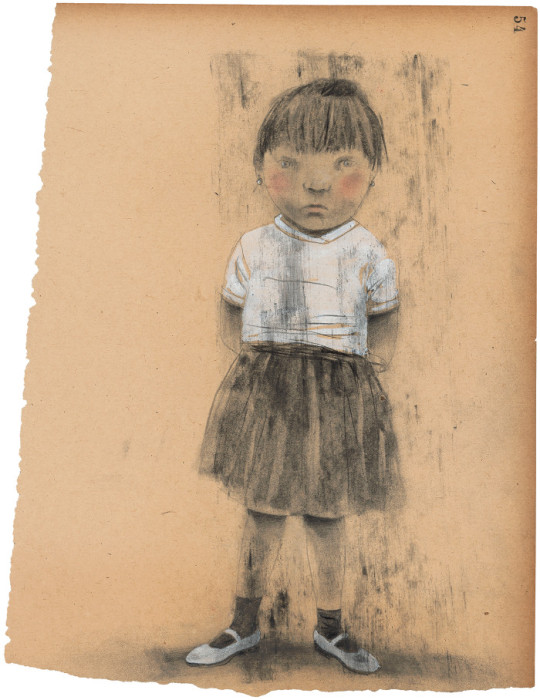

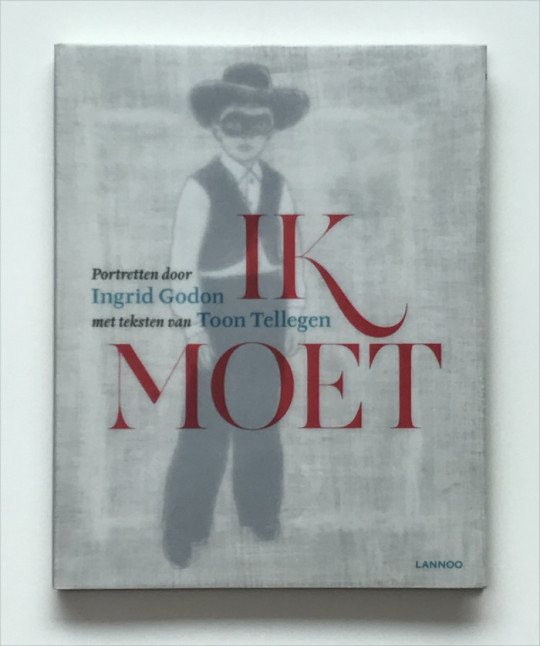

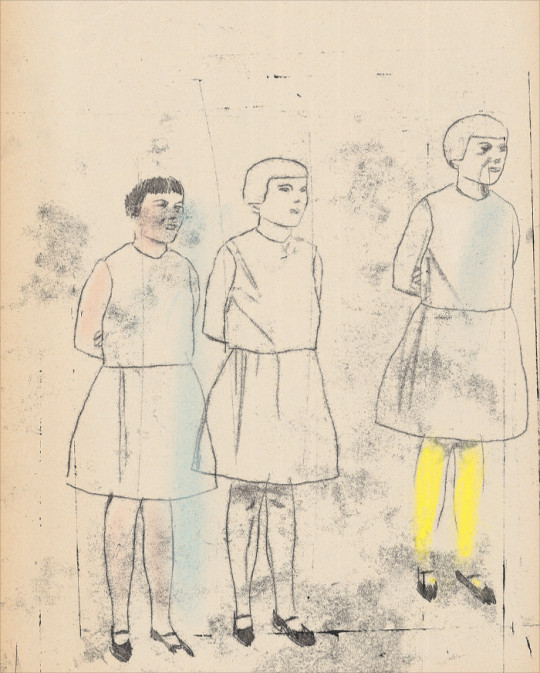

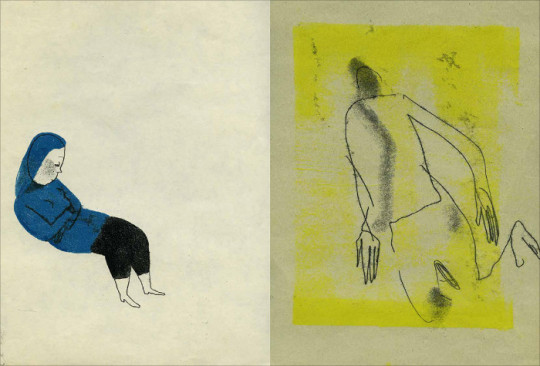

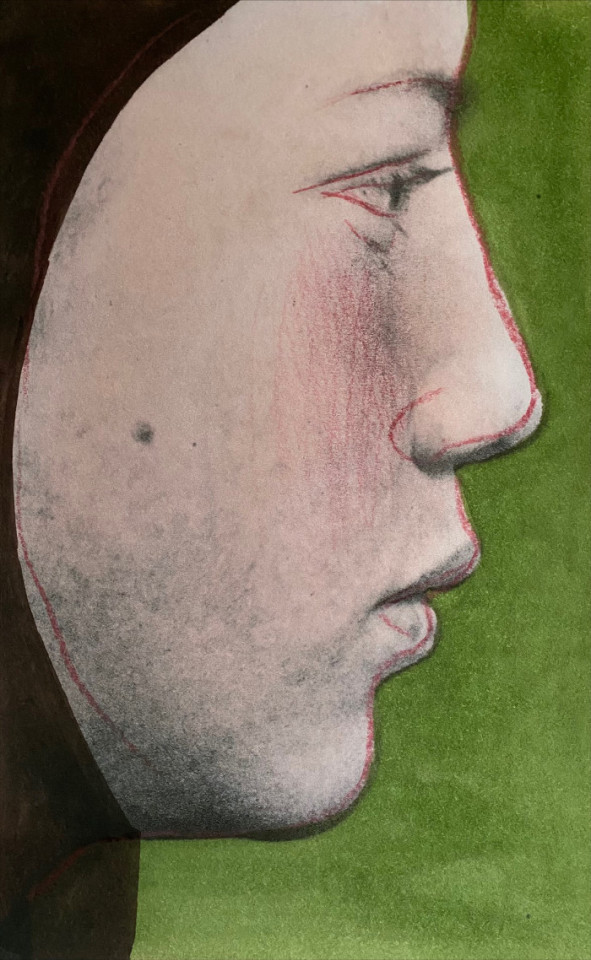

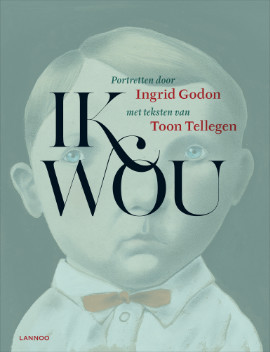

Photography has played an important role in my life for a long time now. A series of photographs could grab me, and I could go to work with it. For instance, I became enthralled by the work of Belgian photographer Norbert Ghisoland. He made portraits of ordinary people in his studio in the Borinage, an industrial region, each of them dressed to the nines, but there is a great deal of misery behind the well-groomed facade. This became the foundation for my work which was mainly aimed at adults: IK WOU (I Wish). Toon Tellegen wrote the text for the first series of portraits for this book; 33 portraits of serious people. Dressed to the nines. I drew them.

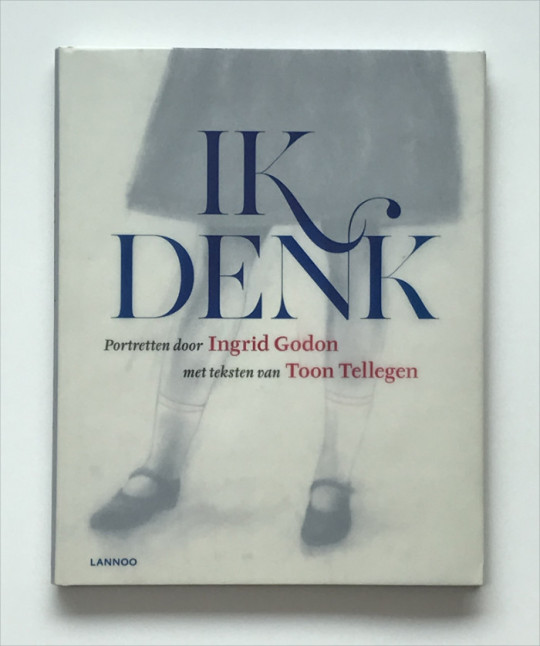

IK WOU became a trilogy, with IK DENK (I Think) and IK MOET (I Must) as parts two and three.

The trilogy has been successful, not just in Belgium and The Netherlands, but also in the French and German-language regions. It also led to beautiful exhibitions, with a large exhibit in Frankfurt being the tentative highlight. In Cologne, I displayed the works from IK WOU in combination with the children’s portraits of August Sander in 2016. I WISH, the American edition of IK WOU, was published in the spring of 2020. At the end of 2020, its portraits were supposed to be in an exhibition at C.G. Boerner in New York City, but this was cancelled due to Covid-19.

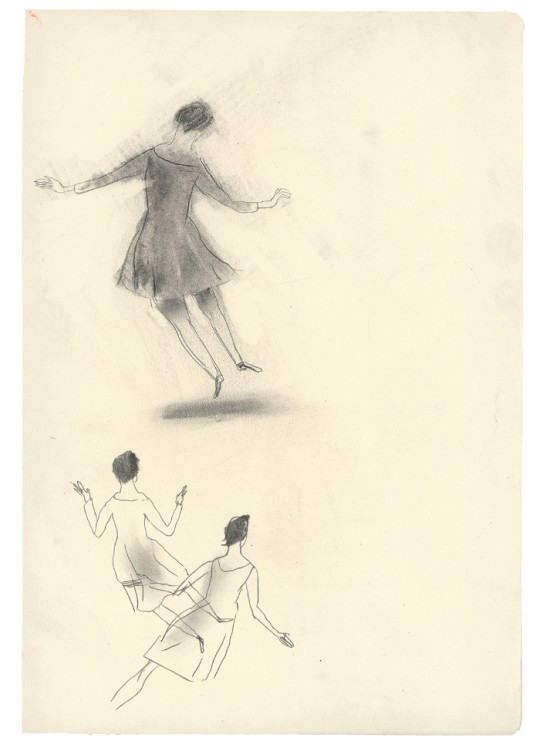

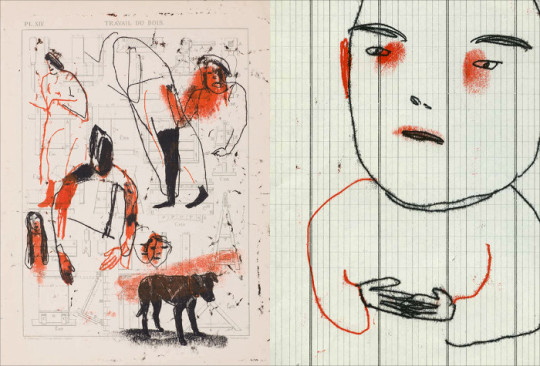

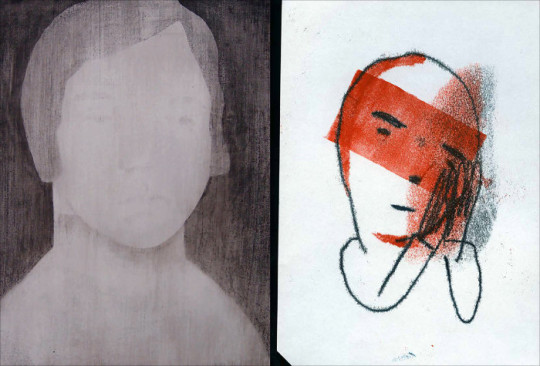

2018 was an important year for me. For the first time, I made a book without a story. Unless the viewer finds a story in there, of course. DANTESKEN: over 600 pages of drawings, an explosion of what goes on in my head. For me as an artist – because that is how I finally started seeing myself as well – this was an important step. More than ever before, I realised the importance of entrusting the paper (or canvas or wood or printing press or clay or fabric) with lines and shapes. I can do no different. I keep drawing.

Recently, I started making little sculptures out of fabric: three-dimensional drawings, like puppets stepping out of my drawings.

I’ve also been working more and more with ceramics and textile art.

My work is becoming increasingly autonomous, and diverges more and more from merely illustrating. Drawings live lives of their own, become works in their own right, sometimes with a story, sometimes starting from a story, sometimes from nothing.

I have no style; I have the Ingrid Godon style. I’m continuously looking for the right way to tell my story, rustling around in my box of materials, alternating between pencil and paint, covering it with a paint roller, cutting into wood and printing it, scribbling on photographs. I keep searching.

I mainly draw people who – like me – look in all directions and are curious about what goes on in front of them. They sometimes look away, but they are always very present. I have at times – on request – drawn landscapes. But even then, I could not resist placing a person in the landscape here and there. Looking, like I do. I search continuously, take different paths, and keep looking. Full of wonder.

In the meantime, I keep working on commissions, I take the initiative to make books, I keep searching for the right pen line or brush stroke, the images keep flowing from my head, and I keep drawing. I draw and I draw.

Illustrations © Ingrid Godon. Post translated by Gengo and edited by dPICTUS.

Buy the English edition

Ik Wou / I Wish

Ingrid Godon & Toon Tellegen

Lannoo, Belgium, 2011

‘Pairs portraits with poetry to articulate wrenching individualism, yearning, humour, desires, and pathos. This probing psychological journey makes for an exciting exploration in empathy.’ —Kirkus Reviews

‘Each face is round as the moon, with small shining eyes that sit curiously far apart... One boy wears a bellhop’s uniform; another, a red jersey and cap... By voicing the fears, angers, and secret desires of the figures, Tellegen spurs readers to embrace those of others, and their own.’ —Publishers Weekly

Dutch: Lannoo

English: Elsewhere Editions

German: Mixtvision

French: La joie de lire

Buy this book

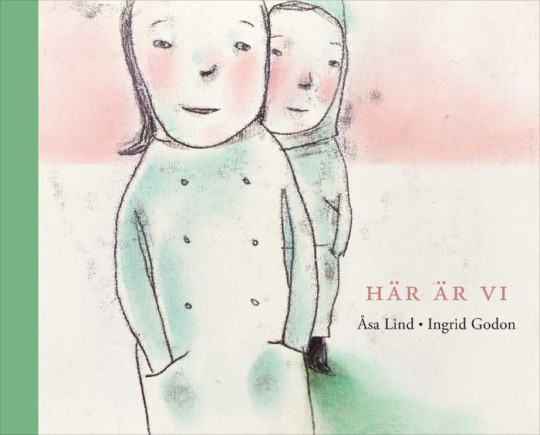

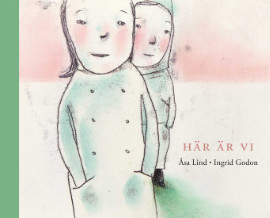

Här är vi / Here we are

Åsa Lind & Ingrid Godon

Lilla Piratförlaget, Sweden, 2017

What happens when we become us? And how do we look at them? Belonging and not belonging is the theme of this poetic picturebook. Åsa Lind is one of Sweden’s most loved authors, and Ingrid Godon is an award-winning Belgian illustrator. Together they have created an unforgettable story about us and them.

Buy this book

Dantesken

Ingrid Godon

MER / Borgerhoff & Lambrechts, Belgium, 2018

Who are the creatures that populate Ingrid Godon’s drawings? They are people, sure. But what is there of a person who only exists as an image? In this book we travel through the works of a gifted artist, illustrator and image maker.

Who will we meet? Who, or what, will we recognise? A book with 800 images which speak for themselves.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Axel Scheffler

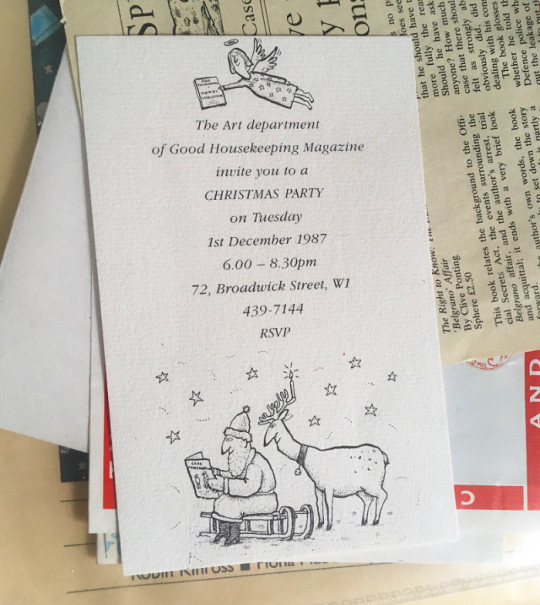

In this post, Axel takes us on a journey through his art studio and career. As well as sharing wonderful development work from some of his much-loved picturebooks, he shows us unseen sketchbook pages, early illustration commissions, etchings he made as a student, and his recent work to educate children about the coronavirus.

Visit Axel Scheffler’s website

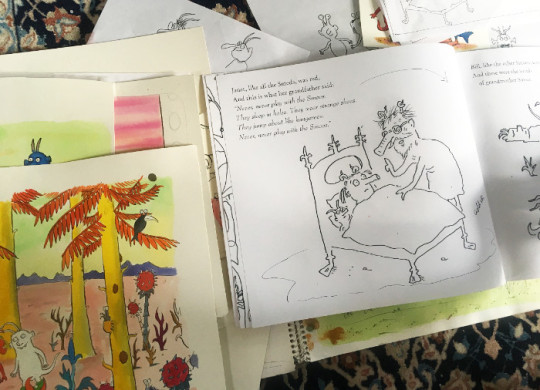

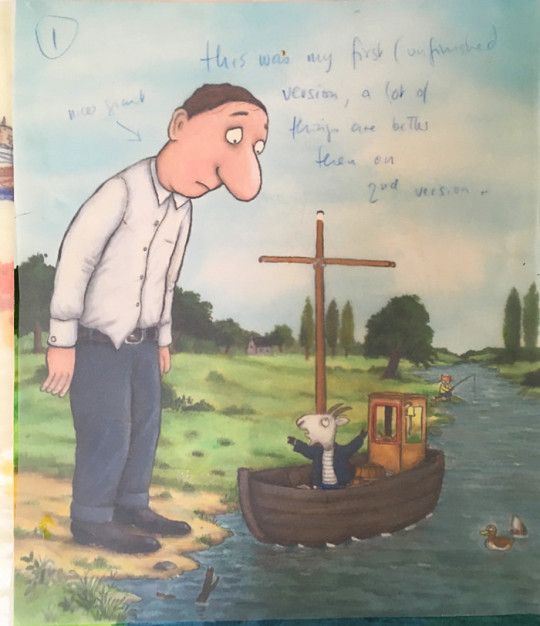

Axel: I’m not really sure how many books I’ve illustrated in the 30+ years that I’ve been working. Over 150. I mostly work for the UK market, but occasionally I do books with German publishers. Not picturebooks though, so nothing that collides with the co-edition market.

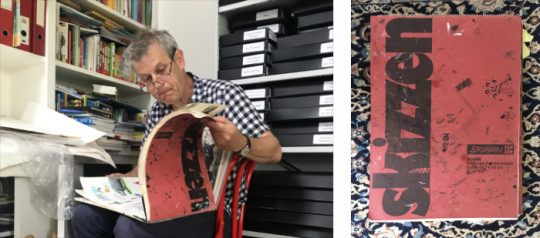

Each of the boxes you see here contains one of my books: the sketches, illustrations, dummies, alternate versions of covers, everything.

I organised these boxes with Liz, my assistant, to have all the main books there so we can find things for exhibitions. There’s still lots of drawings in these boxes which aren’t sorted yet. Liz is such a great help, but it’s very difficult for me to keep on top of everything. I think I would probably need two Lizes, or perhaps three.

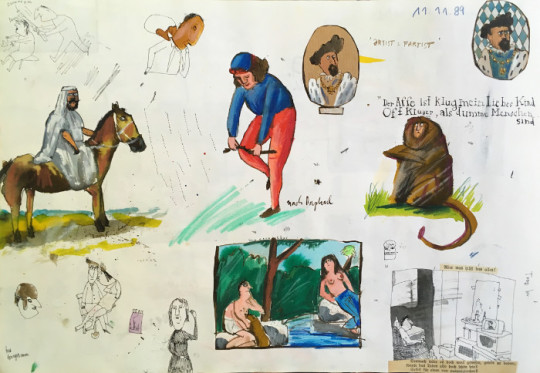

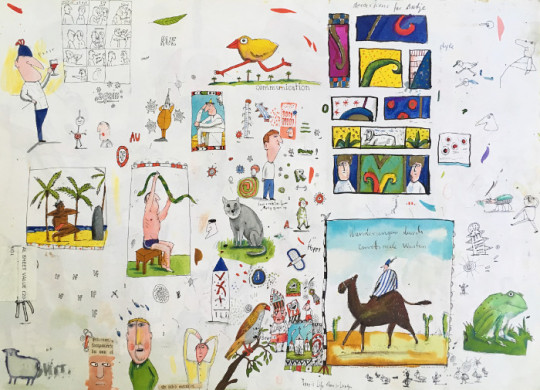

So yes, I don’t really know where to begin... I’ve got endless sketchbooks and little drawings on paper. I’ve got some really old sketchbooks I could show you.

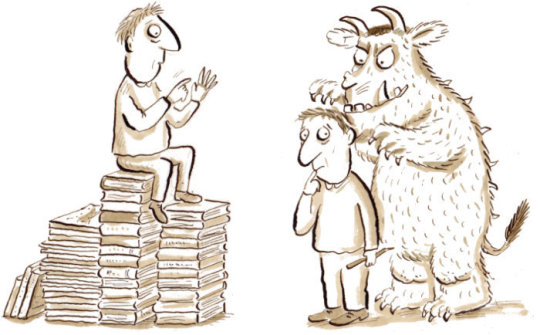

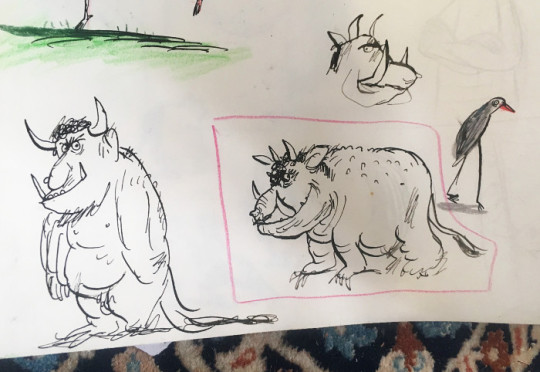

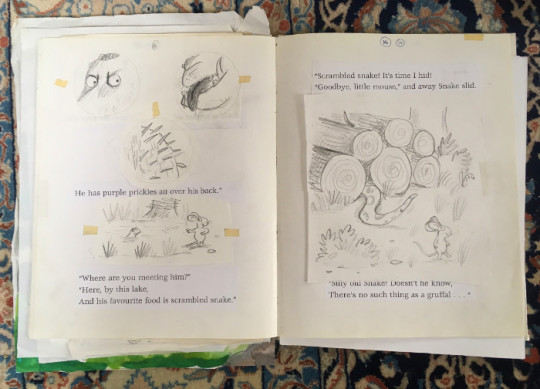

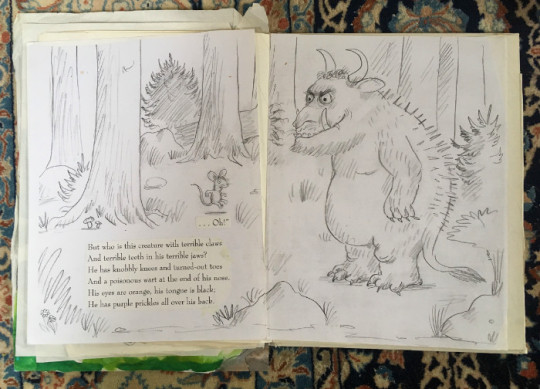

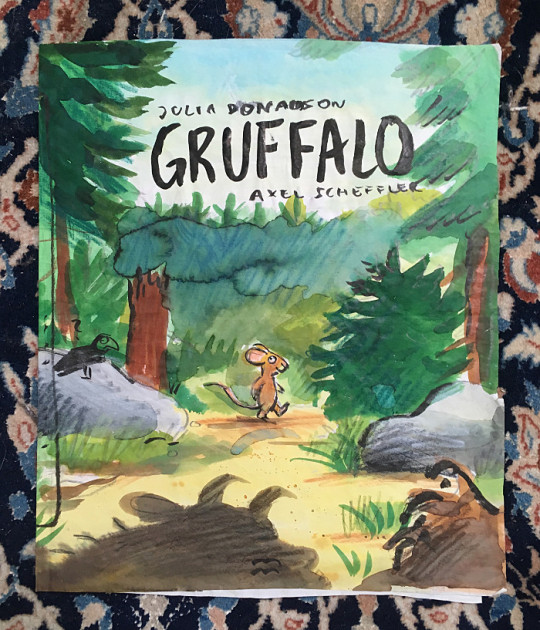

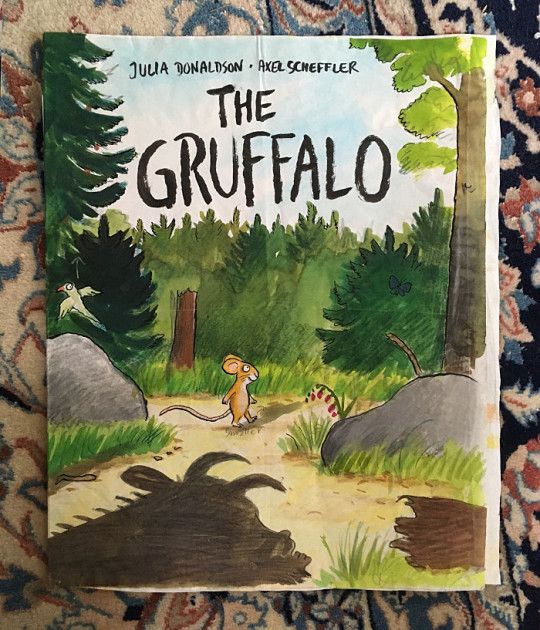

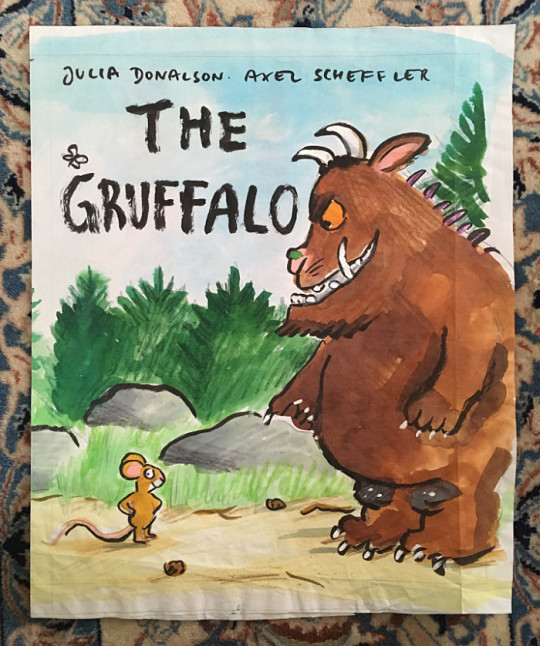

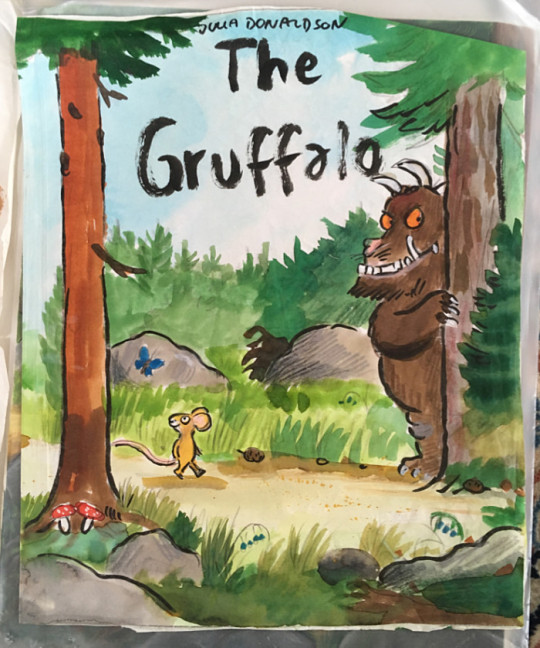

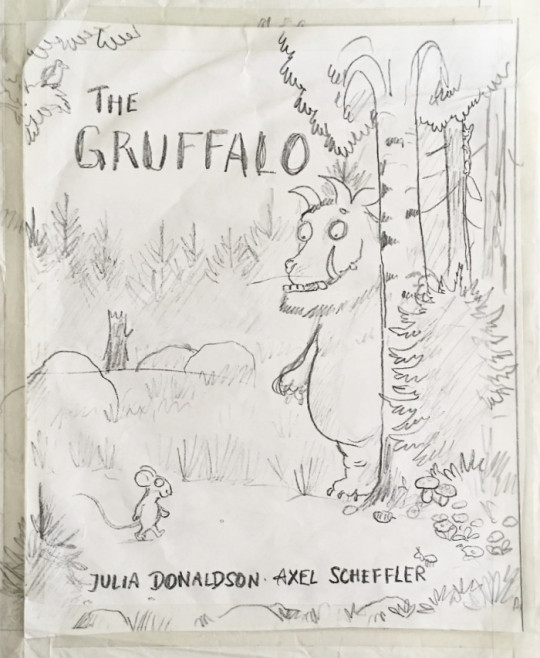

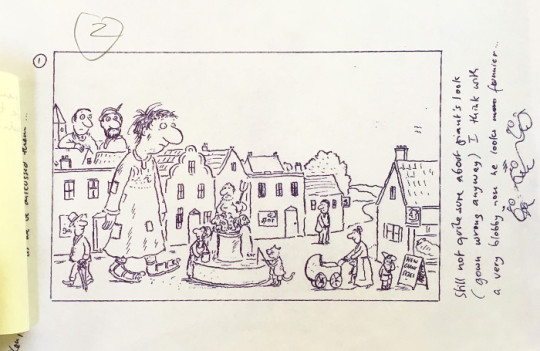

Shall we start with The Gruffalo?

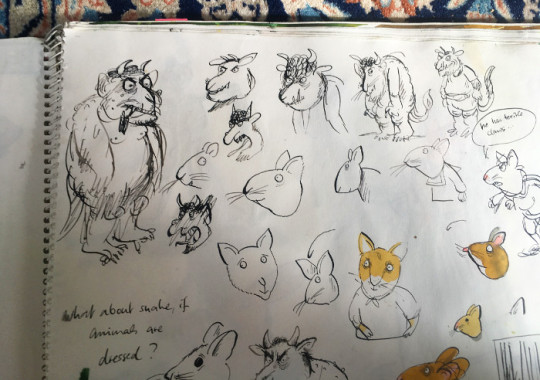

My early sketches of the Gruffalo were thought by my editor to be too scary for small children. So I had to make him a bit rounder and more ‘cuddly’. Initially, I‘d also thought that all the animals would be wearing clothes, as they often do in picturebooks. But Julia had different ideas, and to be honest I was relieved. How would I have dressed the snake?

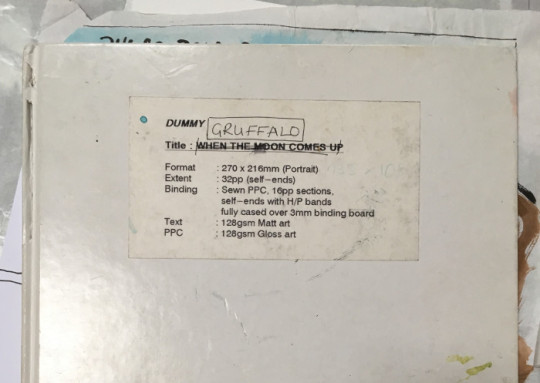

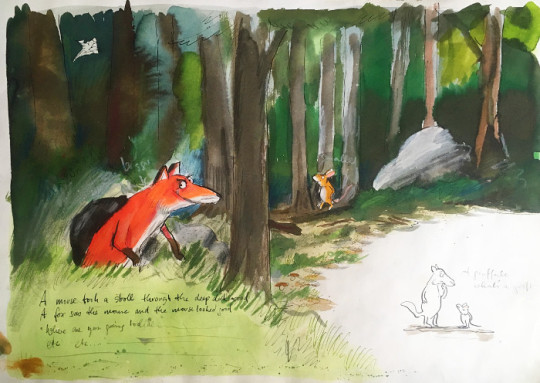

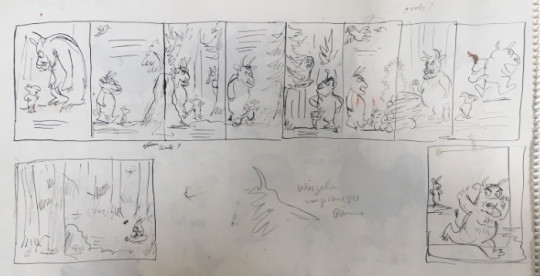

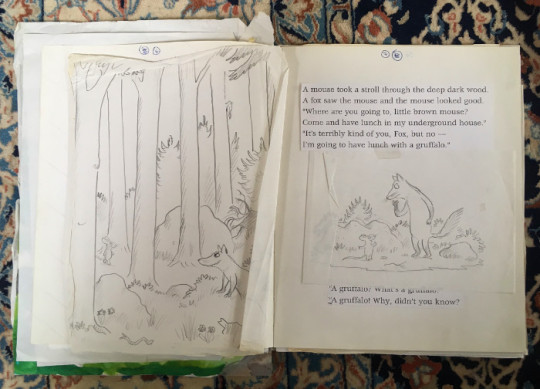

Here’s some spreads from the dummy...

I tried a lot of alternate covers for this book; I think there were twelve in total. There’s some where the Gruffalo doesn’t even feature on the cover.

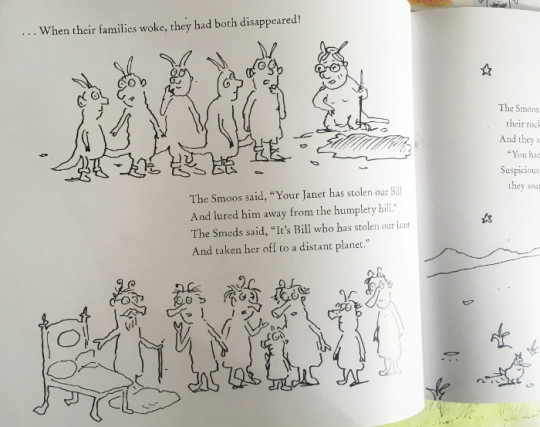

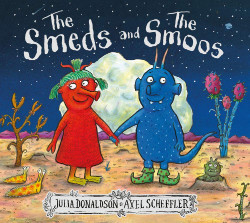

My latest book with Julia is called ‘The Smeds and The Smoos’. It was quite nice to work on because it’s so different from the other books we’ve done together. The text is a bit like a mixture between Dr Seuss and Lewis Carol; it has this nonsense element. But it’s basically Romeo and Juliet in outer space.

It’s an alien story, so I didn’t have to draw any rabbits or squirrels for a change, and I could invent more. I had more freedom. But like always, I got bored with drawing the same characters over and over again. But that’s picturebooks.

There was quite a lot of development work in the case of this book. But when it’s a story about a fox or a squirrel, I don’t do this kind of stuff. Over the years, it’s become much quicker and easier working on my books. I do far less research than I used to. Now I generally just do a quick pencil sketch then go straight to artwork.

Sometimes I have to start again because things go wrong though. This was a finished piece that was abandoned. I think I suddenly thought that the rocket was far too big or something. I do that; I work on something for ages, and then I suddenly look at it from a distance and realise that something needs redoing.

Did you spot the little Gruffalo in this picture? Since ‘The Snail and the Whale’, I’ve hidden a Gruffalo in each of my books with Julia (not ‘The Ugly Five’ though).

For almost all of the books Julia and I have done together, our editor has been Alison Green. We’re an old established team. And I’ve always worked with the publisher Kate Wilson; I followed her from Macmillan to Scholastic, and then to Nosy Crow. Julia moved from Macmillan to Scholastic, and decided to stay there. So Julia and I have some of our joint titles with Macmillan and some with Scholastic. Julia does books with other illustrators for Macmillan, and I illustrate other books for Nosy Crow.

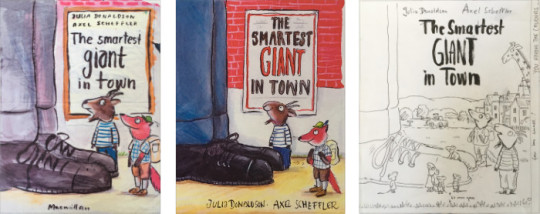

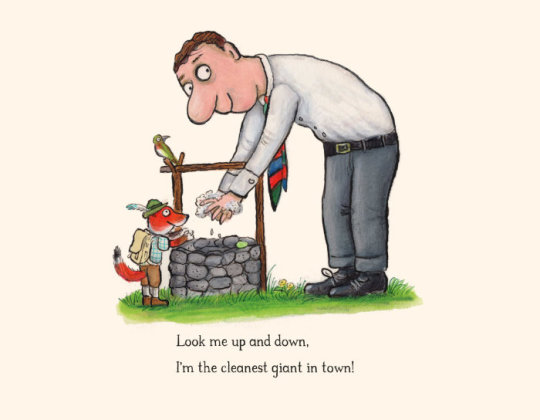

People often ask me which of the books I’ve done with Julia is my favourite. It’s quite hard to choose, but I enjoyed working on ‘The Smartest Giant in Town’. I liked the way I could do a crazy world with animals, giants, fairytale characters, everything mixed together without anyone caring or questioning it. I’ll show you a few things from the box...

For this book, the cover was changed at the last minute. The original design had the title written on a poster stuck on a brick wall, but the sales people said they wanted a landscape, so I did another one. Years later, they used the original design for a new paperback edition, so it wasn’t completely wasted in the end.

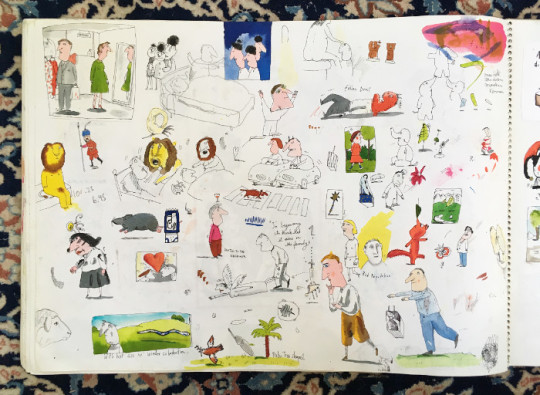

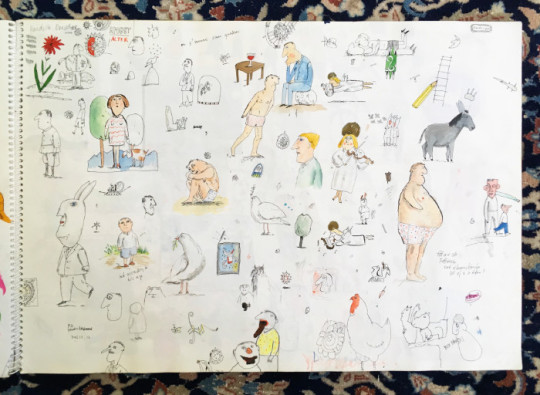

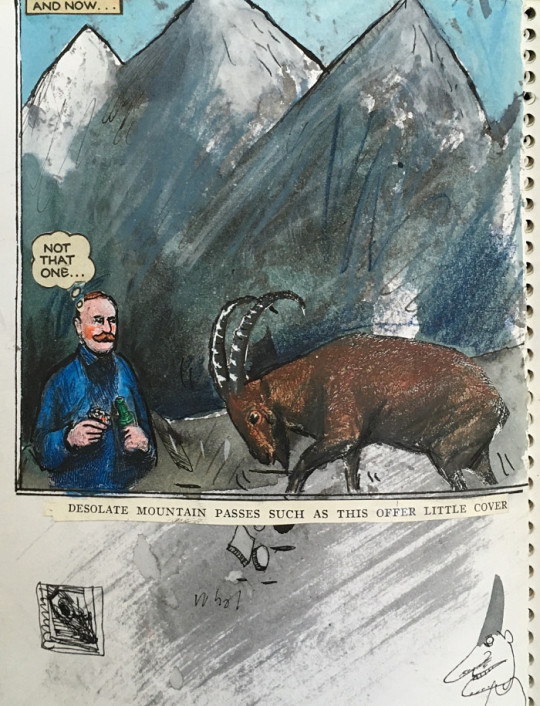

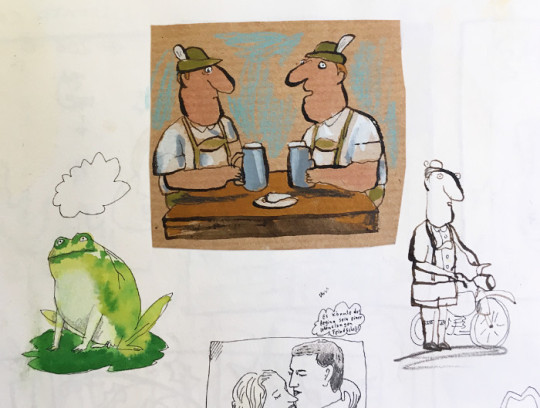

I mentioned my endless sketchbooks earlier. I’ll show you a few of them. This was mainly me playing around without thinking about what I was doing; it wasn’t a conscious thing.

I haven’t looked at these sketchbooks for ages. It was such a long time ago. I don’t work in sketchbooks like this anymore, and I no longer doodle. But for fun, I make illustrated envelopes for friends.

I often think about doing a book with just pictures, but I’m always too busy doing other things. Posthumously, perhaps there will be time to do this. I’d also love to experiment and be more spontaneous; it’s been my dream for decades to do something completely different. But when I receive a book project, I always feel under pressure to finish it, and I’m always late with everything, so I end up doing it the way I’ve always done it.

This is my drawing table, which is and always has been too small and too messy. I think I have to accept it will always be this way.

I use Saunders Waterford paper for my illustrations. It’s funny how we all have our special paper. My rough sketches are often quite small, so I have them blown up to the correct size. Then I trace the sketches on a lightbox onto my watercolour paper. After that, I draw the outlines in black ink with a dip pen. I colour everything with Ecoline inks using brushes, and then coloured pencils on top of it (I use Faber Polychromos and Prismacolour crayons). I might then need to redraw some of the black lines, or use some white gouache for highlights.

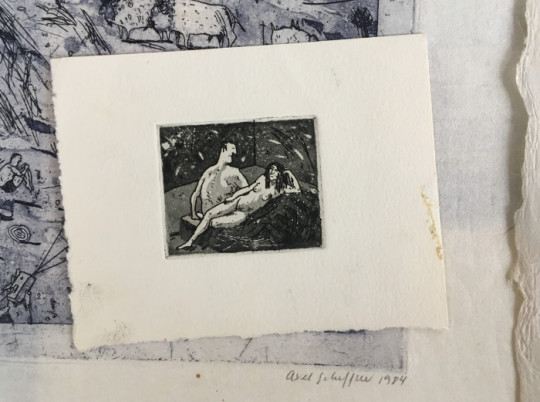

I studied History of Art in Hamburg, but left before graduating. I realised this wasn’t what I was good at; I’m not an academic.

Then I had to do my alternative service as conscientious objector. Sixteen months. There was still conscription then; that’s how old I am. I worked with mentally ill people in their homes. It was during this time that I had a friend studying ceramics at Bath Academy of Art in England. I went to visit her. I really didn’t know what else to do, so I thought maybe I could move to Bath and go to the art school. So this is what I did. The course was Visual Communications, so it was design, printmaking, photography, all that stuff. But I realised I only wanted to do illustration.

I’d gone to art college hoping to learn something. I don’t think that necessarily happened, but drawing intensively for three years was, I think, what I had needed to do. I don’t remember actually finishing any projects though.

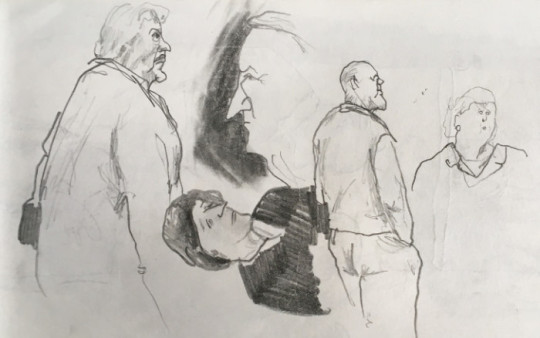

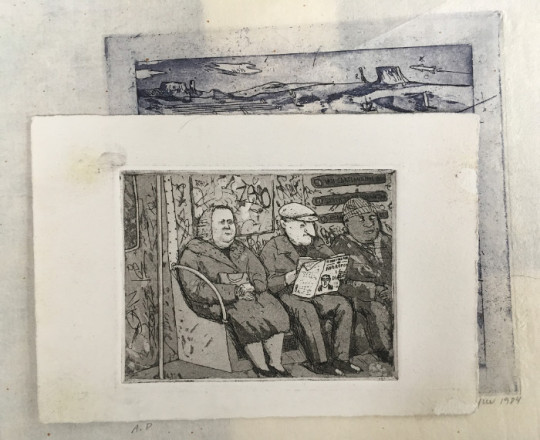

Here’s some drawings from my student sketchbooks. I did lots of observational drawing back then, which I don’t anymore. I did it then because they told us to. I’m an obedient person!

While I was a student, I did an exchange in New York: Cooper Union Art College for three months. These drawings are of Jewish immigrants, meeting for coffee. It was 1984, so many of them were still alive; refugees from Germany or Austria. I heard them speaking German, so that’s how I knew.

Sketchbooks are such a good way of memorising things. Nobody really knows about these sketchbooks; I used to take them to interviews, but they’ve been hidden away for years.

After I graduated, I moved to London and took my portfolio around. My art teacher had suggested I should do this to get work, so that’s what I did. In those days, you had to ring them and ask to come around. I got two commissions straight away, and it’s been busy ever since, really. I’ve always had something to do.

Here’s some of my early commissions. Starting from 1985, I guess. Very pointy noses...

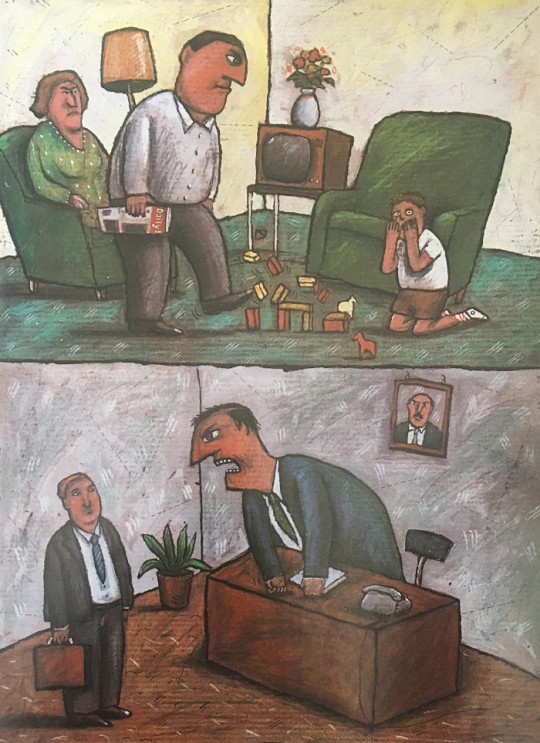

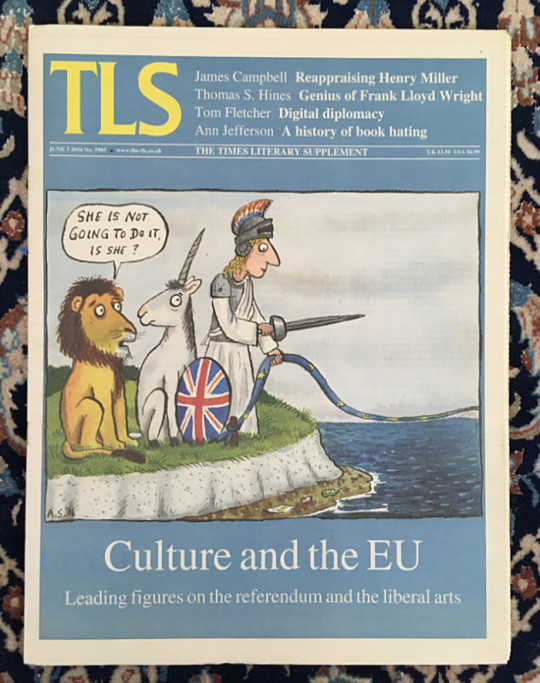

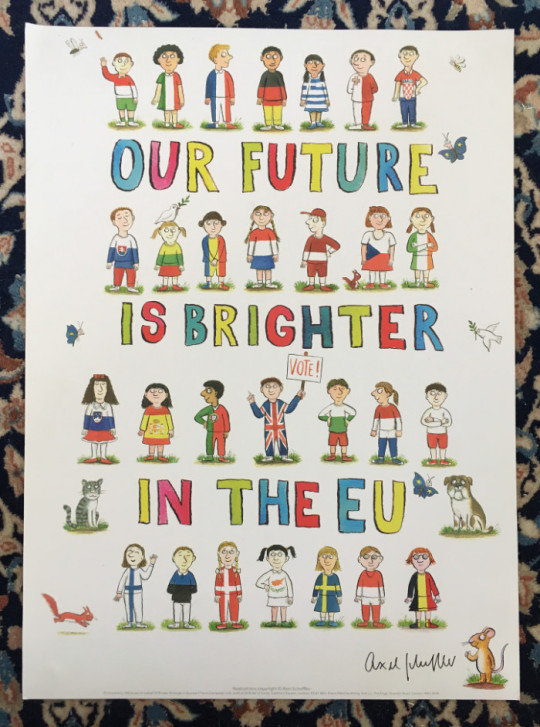

I did so much of this kind of work. It was a good way of earning money quickly. Occasionally, I still do editorial. I did some Brexit drawings for the remain campaign. Sadly, it didn’t help. Maybe I wrecked everything!

I’ll say a few words about the KIND book... 38 wonderful artists donated a picture to illustrate some of the many ways children can be kind. Such as sharing their toys or helping people from other countries to feel welcome.

One pound from each book sold goes to the Three Peas charity, which supports refugees from war-torn countries. It’s been a big success so far, and Three Peas has received a lot of money from sales in the UK and co-editions.

I’d quite like to do the UNKIND book next! I think illustrators would probably enjoy that, but I don’t imagine it would sell very well.

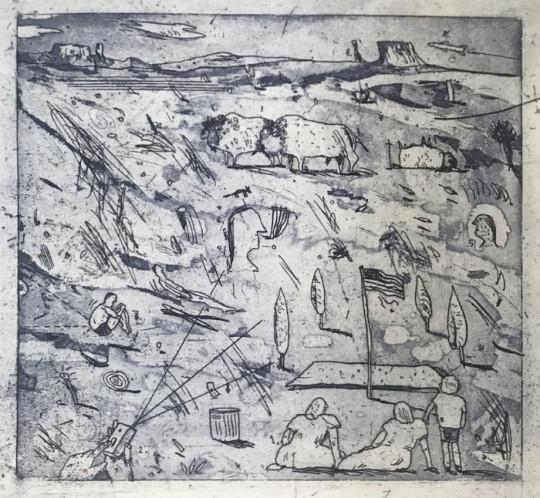

And now for something completely different! Some etchings I made when I was a student.

People often ask me which illustrators I’m inspired by. I don’t seek any direct influence on my work, but I’ve always said that Tomi Ungerer had the greatest influence on my approach to illustration. Although his style is quite different to mine, this humour and wackiness is something that has always appealed to me. And the details.

William Steig is someone I got into later, when I was already illustrating. And Edward Gorey of course. And Saul Steinberg. I think the Czech artist Jiří Šalamoun is wonderful. And I like Eva Lindström from Sweden a lot. She’s so great.

Okay, to finish with I’ll talk about the coronavirus work I’ve been doing...

I asked myself what I could do as a children’s illustrator to inform, as well as entertain, my readers here and abroad about the coronavirus. So I was glad when Nosy Crow asked me to illustrate a book on the subject. I think it’s extremely important for children and families to have access to reliable information in this unprecedented crisis.

You can download the free digital book in English here, and in over 60 other languages here.

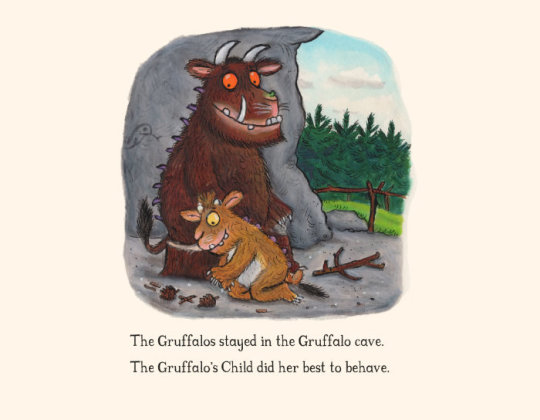

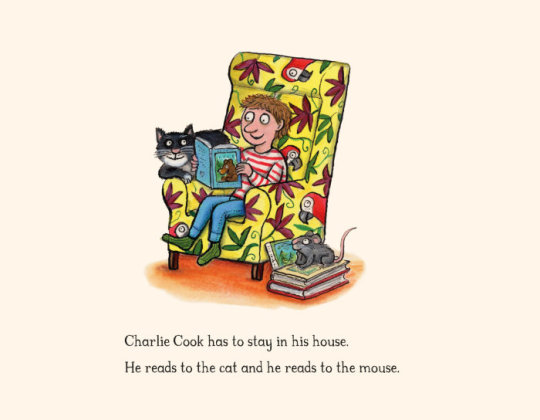

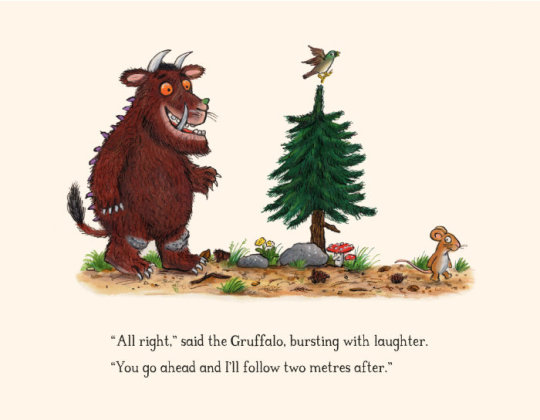

I also wanted to do something light-hearted to cheer people up, and I thought, “What if I imagine some of our characters in corona situations?” Julia liked the idea and wrote rhymes for the new scenes. This was really more about entertainment than serious information.

Artwork and verse © Axel Scheffler and Julia Donaldson 2020. Based on characters from ‘The Gruffalo’s Child’ (2004), ‘Charlie Cook’s Favourite Book’ (2005), ‘The Smartest Giant in Town’ (2002), and ‘The Gruffalo’ (1999) — © Macmillan Children’s Books.

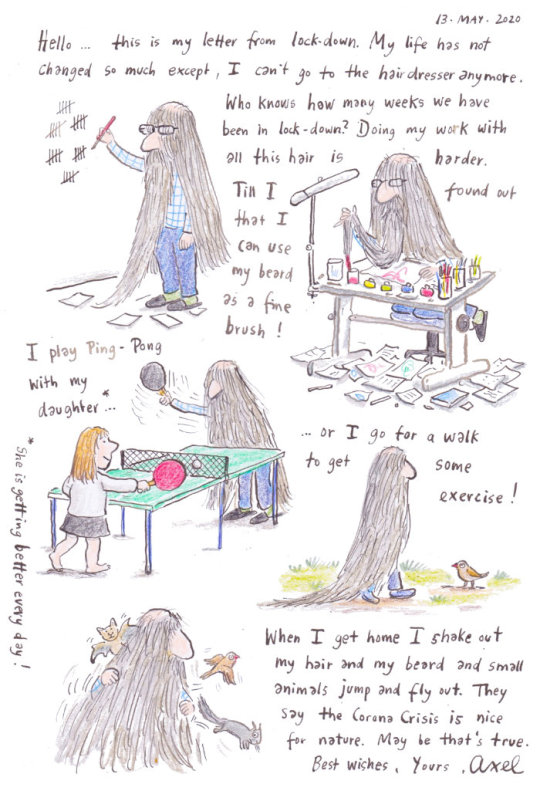

And here’s one more thing: my ‘letter from lockdown’. On The Children’s Bookshow website, you’ll find lockdown letters from lots of other wonderful authors and illustrators.

Illustrations © Axel Scheffler. Post edited by dPICTUS.

Buy this picturebook

The Gruffalo

Julia Donaldson & Axel Scheffler

Macmillan Children’s Books, UK, 1999

‘A mouse took a stroll through the deep dark wood. A fox saw the mouse and the mouse looked good.’

Walk further into the deep dark wood, and discover what happens when a quick-witted mouse comes face to face with an owl, a snake... and a hungry Gruffalo!

‘The Gruffalo’ has become a bestselling phenomenon across the world. This award-winning rhyming story of a mouse and a monster is now a modern classic, and will enchant children for years to come.

PUBLISHED IN THE FOLLOWING LANGUAGES & DIALECTS

Afrikaans

Albanian

Arabic

Australian

Azerbaijani

Basque

Belarusian

Bengali

Breton

Bulgaria

Catalan

Chinese (Simplified)

Chinese (Traditional)

Corsu

Croatian

Czech

Danish

Doric

Dundonian

Dutch

English

Esperanto

Estonian

Faroese

Farsi

Finnish

French

Frisian

Gaelic

Galician

Georgian

German

Glasgow Scots

Greek

Guernésiais

Hebrew

Hindi

Hungarian

Iceland

Indonesian

Irish

Italian

Jèrriais

Kazakh

Kölsch

Korean

Latin

Latvian

Lithuanian

Low German

Lowland Scots

Luxembourgish

Macedonian

Maltese

Manx Gaelic

Maori

Marathi

Mexican Spanish

Mongolian

Norwegian

Orcadian Scots

Polish

Portuguese

Portuguese (Brazil)

Romanian

Russian

Sami

Schwabisch

Serbian

Sesotho

Setswana

Shetland Scots

Slovakian

Slovenian

Spanish

Swedish

Swiss German

Tamil

Thai

Turkish

Ukrainian

US English

Vietnamese

Welsh

Xhosa

Zulu

Buy this picturebook

The Smeds and The Smoos

Julia Donaldson & Axel Scheffler

Alison Green Books, UK, 2019

The Smeds (who are red) never mix with the Smoos (who are blue). So when a young Smed and Smoo fall in love, their families disapprove.

But peace is restored and love conquers all in this happiest of love stories. There’s even a gorgeous purple baby to celebrate!

PUBLISHED IN THE FOLLOWING LANGUAGES

Afrikaans

Catalan

Croatian

Dutch

English

Finnish

French

German

Hebrew

Hungarian

Italian

Korean

Luxenbourghish

Polish

Russian

Slovenian

Spanish

Swedish

Turkish

Ukrainian

Buy this picturebook

Kind

Alison Green, Axel Scheffler & 38 illustrators

Alison Green Books, UK, 2019

Imagine a world where everyone is kind; how can we make that come true? With gorgeous pictures by a host of top illustrators, KIND is a timely, inspiring picturebook about the many ways children can be kind, from sharing their toys and games, to helping those from other countries feel welcome.

One pound from the sale of each printed copy will go to the Three Peas charity, which gives vital help to refugees from war-torn countries.

PUBLISHED IN THE FOLLOWING LANGUAGES

Bulgarian

Catalan

Chinese (Simplified)

Chinese (Traditional)

English

French

German

Greek

Hebrew

Italian

Korean

Netherlands

Portuguese (Brazil)

Romanian

Spanish

Swedish

Turkish

Vietnamese

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

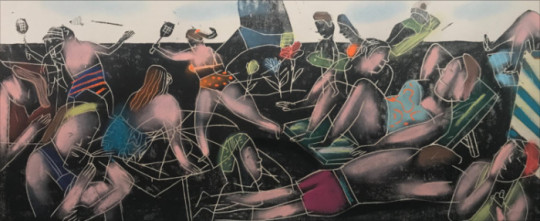

ATAK

In this post, ATAK talks about his fascinating creation process and he shares illustrations and development work from some of his wonderful books – including sketchbook pages for his forthcoming picturebook ‘Piraten im Garten’, which is due to be published in 2020.

Visit ATAK’s website

ATAK: My process is like hip-hop. Mixing and sampling.

I have a big box where I put material that I’ve found on the street or in magazines. Then in the summer, when I’m sitting in the summer house, I stick everything into sketchbooks.

These are important books for me. I often use them when I’m looking for an idea. I like to make connections between this and that.

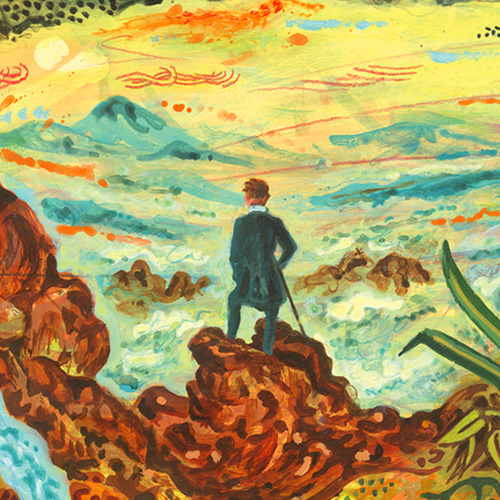

Sometimes I steal things. Here’s an example of where I used a painting by Caspar David Friedrich in one of my images. This is a very important painting for the German culture; it’s romantic. It’s the first painting that’s like a window. You see with him and you’re led into the picture.

‘Wanderer above the Sea of Fog’, Caspar David Friedrich, 1818.

When I take something to use in my own work, it’s more about the idea of composition and atmosphere. It’s not just a reference that people will know.

This is the sketchbook for my picturebook ‘Topsy Turvy World’. The publisher asked me for a book for children, and as I was tired of working with long texts, I thought this one should be a wordless book, where the images tell the whole story.

We have a German tradition from the 18th century of ‘bilderbogen’. This is like the origin of comics. They’re one-page stories. I was looking at some of these and I found some interesting ideas for ‘Topsy Turvy World’.

Here are some pages from the sketchbook.

Not everything made it into the final book; some of it was too heavy for my publisher, so he kicked it out. The smoking people had to go, otherwise we couldn’t have sold the rights in America.

Then there was a problem... My sketches had a lot of life and were fully-worked, so to transform them into the final artwork was very hard. After the rough version, I had this feeling that I was already finished with the book. Making the final ‘clean’ artwork felt like a kind of discipline.

My original paintings are always much bigger than they appear in the books. I never work to the correct size or format.

I often sell my paintings, but here is one I’ll never sell. It was done for the first children’s book I made, called ‘Comment la mort est revenue à la vie’ (How death came back to life), written by Muriel Bloch and published by Thierry Magnier.

It’s an important painting for me. I came from the comic world – black and white graphics – where I would draw out the whole scenes with all the details. In the middle of working on this painting, I had to go out to buy some food, and then I came back and thought, “Oh, it’s enough.” There’s a big difference when you work with colour. It’s like a sound, like a kind of music. This painting was very important for me in understanding colour.

Before I start working on an image, I often have a rough idea of what’s going to happen in the scene, but I leave a lot of space for other things to come in... And when I’ve started to work, I might see something in my studio or in a book, and it goes into the image.

I like this open process. And I like to be surprised. It’s very important for me that I don’t know in the beginning exactly what’s going to happen.

My way of painting is very old school. Traditional. Sometimes I paint over the top of something and you can see the trace of it behind. You can’t really fake things like this on the computer. For me, my original artwork is more important than the finished book. I once had an interesting discussion about this with Blexbolex. It’s completely the opposite for him: he sees his books as being the original artwork.

After ‘Topsy Turvy World’, I made a book called ‘The Garden’.

The original German edition was almost like a book for bourgeoise women... But for the French edition, they reimagined it for kids. It’s much bigger; you can really go inside. And the French publisher asked me to make some flaps to open up on the pages, which were not there in the original edition.

The sketches for ‘The Garden’ are almost nothing. It was very important that I didn’t repeat the process of ‘Topsy Turvy World’, where the sketches were very close to the finished artwork. I couldn’t work like this again. So the sketches here are very loose, but I knew exactly what was supposed to be in the pictures.

Working like this, you must have a very strong relationship with the publisher – one of absolute trust. I also have big problems with deadlines; I’m always late. With this book, my publisher Antje Kunstmann was so good. She phoned me every morning: “Hallo, here is Antje!” It was so important to know she was there, almost like a mother. It was a similar story with Wolf Erlbruch and his book ‘Duck, Death and the Tulip’. He was working for four years on this book. In the end, Antje came to his home and was waiting on his sofa for two days to take the last drawing!

The latest children’s book I made is called ‘Martha’.

I started working on it after reading an article in National Geographic about the passenger pigeon. I was fascinated. Because it’s a real story, it was not easy for me to make this book. It’s easier when I’m given a text because I have more distance.

Again, I worked very loosely in my sketchbook. These sketches are just indications – so I know something is here or somebody is there. It does help me that things are more open.

I don’t have sketchbooks where I draw from reality. I’m not good at this. You’ll never find me sitting in a crowd, making sketches. I watch and I observe instead. And I have books where I write ideas or note down interesting forms and shapes that I see.

Here are some pictures from ‘Martha’.

And here’s an idea for the dust jacket, where the kids could cut and draw on the paper, and make origami out of it to give a kind of rebirth. Martha is gone, but maybe she’s not gone if the kids could bring her back. The publisher didn’t go for this idea.

I went to art school but never finished. Just after the Berlin Wall came down, I was studying visual communication. There wasn’t a good atmosphere at my art school. I wanted to find like-minded people and work as a team, but it felt like most of the students were only interested in being artists, but not in working together. Then my daughter was born, and I never finished art school.

I’m now teaching art as a professor. The other teachers have diplomas, and I feel like I’ve come from the working class. I do like intellectual work, but when I work with students, I want to see something. I can only talk about what I see. I need it very visual. It has to catch me.

From when I was nine years old, I wanted to be an illustrator. In east Germany, illustration was a part of publishing. All the novels had illustration. It’s still unique now to see this, but in east Germany it was normal... So my plan was always to be an illustrator. This way I could wake up when I wanted, have no boss, listen to my music all day, and make my own work.

Speaking of music... The type of music I listen to when I work depends on the specifics of the book. For example, I made a book for Nobrow called ‘Ada’ (from a word portrait by Gertrude Stein). The idea for the artwork was to make handmade pixels, so I listened to a lot of electronic music; ping–ping–ping! It’s about energies. And for me, the music is also very important because I travel a lot and it can be hard to come back to your work – but when I listen to the music, immediately I’m back in the project, in the zone. It’s all connected – the music with the book.

Here’s my playlist for ‘Martha’.

Distortions – Clinic Go – Sparklehorse & The Flaming Lips VCR – The XX Song For A Warrior – Swans Avril 14th – Aphex Twin Quiet Music – Nico Muhly First Song For B – Devendra Banhart Last Song For B – Devendra Banhart How Can You Mend A Broken Heart? – Al Green Ash Black Veil – Apparat I Know They Say – Spectrum Opus 55 – Dustin O’Halloran Lost Fur – Karen O & The Kids Unfinished Business – The Go-Betweens Sometimes – My Bloody Valentine Lies – Sin Fang Bous Debussy: Suite Bergamasque, L 75 - Clair De Lune – Alexis Weissenberg Nimrod (Adagio) – David Hirschfelder Atmosphere – Joy Division Still Life – Elliot Goldenthal The Lake – Antony & The Jonhsons Flying Birds – RZA

I used to make hardcore comics with friends. This was our first, which we made before the wall came down. My work has changed completely. I can’t understand this now; it’s like another man made it! And they are not funny. It’s a very small humour; you really have to look for it.

Then, after my daughter was born, I did my own comic series called ‘Wondertüte’. In the comic scene, everybody told me that this wasn’t a comic. But for me, it was totally a comic. I liked the comic medium, but I didn’t see why there had to be only one way. From all my old comics, this is the one I like the most.