Text

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

The whole self love thing is good and all but some people can’t fathom being loved. They can’t imagine there being anything good about them. So they can’t simply just stop doing unhealthy things, there’s a process.

230K notes

·

View notes

Text

not 2 exaggerate but the good place’s thesis of “if the modern pressures of life were removed, we would inherently seek out opportunities to learn and become better and kinder people” is a more interesting and valuable thing to say about society than anything that’s ever been said about cell phones

218K notes

·

View notes

Text

please don’t forget you’re loved. anxiety lies. people care. you are loved. It’s ok.

86K notes

·

View notes

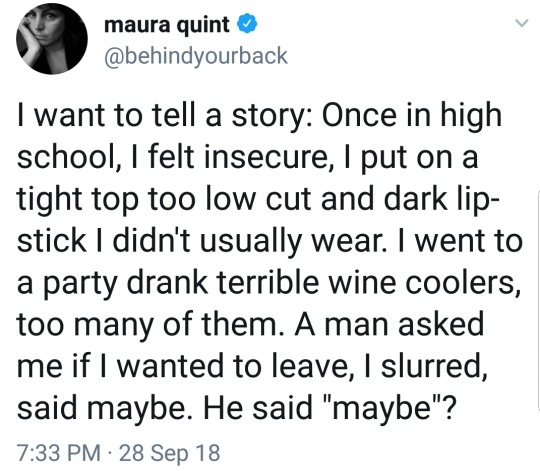

Photo

You don’t love me the same It’s such a fucking shame I’ll never be enough Until it’s too late. You wanna hear my art But only on your terms So learn these fucking words.

136 notes

·

View notes

Photo

You don’t love me the same It’s such a fucking shame I’ll never be enough Until it’s too late. You wanna hear my art But only on your terms So learn these fucking words.

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Feeling Worse After Therapy

Pop culture depictions of therapy often present the idea that therapy is cathartic- that simply attending the session and expressing your thoughts and feelings to your therapist will lead to a release of emotions that will bring you closure, peace, and acceptance, improving your mood immediately.

And that can happen!

But it is very common to leave therapy feeling mentally, physically, and emotionally exhausted, potentially experiencing negative emotions, stress, and/or an increase in other symptoms including urges to engage in dysfunctional coping behaviors. Sometimes that lasts for just a bit after therapy, or for the rest of that day, but sometimes it can linger throughout the week until the next session.

As unpleasant as that is, it is not necessarily a sign that therapy isn’t working. In fact- that exhaustion and increase in negative emotions and symptoms can even be a sign that the therapy is working.

Why?

For a few major reasons:

1. The experience of engaging in therapy- dealing with uncomfortable and distressing emotions, thoughts, experiences, and behavior head-on, disclosing and processing those issues with your therapist, thinking deeply about issues and their cause, making big life decisions –is exhausting. It is hard work! And that work, although it is exhausting, is helpful. It’s like going to physical rehab after an injury- you have carefully but diligently work to build your strength back up. Doing that work is really tiring in the short run, but in the long run you will be stronger, experience less symptoms, and be able to handle emotional things without experiencing as much fatigue.

2. Although disclosing and processing something big (like trauma, but other things too) can be cathartic, it can also have the opposite effect. Particularly when a person has been suppressing or avoiding thoughts/emotions/experiences for a long time, finally releasing it can often feel both cathartic (relief from finally disclosing/expressing) but also painful. It can be difficult to put the emotions back afterword, and the experience of processing can lead to increase re-experiencing symptoms (like flashbacks).

3. Therapy can help people decrease emotional suppression and avoidance. This is great, because when we suppress emotions, we do it unilaterally- by trying to suppress negative emotions, we also suppress positive ones. So when the suppression/avoidance decreases, the amount of both positive and negative emotions is expected to increase. In this case, it’s actually a sign of doing better, although it may not feel that way immediately.

4. The work in and out of therapy often includes dismantling existing but dysfunctional coping mechanisms, and replacing them with new, functional coping mechanisms. That doesn’t all happen in one session- it takes time to identify helpful/functional new coping mechanisms, learn how to use them effectively, and make using them a part of your routine. That means that there are often periods where people are working on reducing use of dysfunctional coping mechanisms but don’t have a totally reliable and effective new coping strategy yet. For example, many people use some sort of avoidance as a dysfunctional coping mechanism. Reducing or ending use of avoidance means approaching emotions/thoughts/behaviors that the person previously felt incapable of approaching, and so starting to reduce avoidance will usually cause an increase in symptoms (like anxiety). After practicing approach strategies instead of avoidance for awhile, those symptoms will decrease and hopefully go away entirely. So again, it’s like physical rehab. In the short term, doing your rehab or your therapy is painful and exhausting and may feel worse than doing nothing at all. But in the long run, all of that work builds you up stronger and gives you new and better ways to manage distress.

Essentially, we expect that some of this will happen for most people. It’s an important although unpleasant part of the therapy process. Again, sort of like recovering from a medical illness or injury- the pain is part of the healing.

So, then, if sometimes good therapy can make you feel worse, how do you know whether your therapy is good-but-painful, or whether it’s just painful? A few things to consider:

1. Did your therapist explain any of this to you? Did they help you understand the potential short-term impacts of therapy, or help you prepare for how to manage short-term increases in symptoms?

2. Did your therapist do any kind of emotional containment at the end of sessions, to help you ‘put the emotions back’ before you leave? Or did they teach you how to do emotional containment on your own?

3. When you told your therapist about your increase in symptoms, were they validating and helpful? Did they respond in a way that helped you understand what was happening? Did they help you figure out what to do about it?

4. Does your increase in fatigue, negative emotions, or other symptoms seem to be tied to specific things happening in therapy? For example, are you more tired after a session of delving deeply into your emotions?

5. Do you find that you are experiencing a mixed bag of improved symptoms vs. worsening symptoms? For example (from the avoidance example above) are you decreasing your avoidance and finding that your anxiety is higher?

6. Do you have clear therapy goals? Are you and your therapist tackling those goals? Do you see yourself making some movement on one or more goals?

If most or all of your answers to the above are ‘yes,’ then probably you are experiencing good-but-painful therapy. If not, it’s worth discussing with your therapist and considering how to improve your experience- either with that therapist or another one.

become a Patron | buy me a coffee | academic consulting | send an ask

631 notes

·

View notes

Photo

HOW TO WRITE A HIGH-GRADE RESEARCH PAPER

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The first time I had to write a research paper for university was one of the most stressful experiences I’d ever had - it was so different to anything I’d ever done before and caused me so much anxiety! It turned out that I’m pretty damn good at writing research reports and I’m now looking to pursue a career in psychological research.

I have never received less than a First (or 4.0 GPA for you American studiers) in my research papers so I thought I’d share my top tips on how to write a kick-ass, high-grade research paper.

*disclaimer: I am a psychology student, my tips are based on my personal experience of writing up psychological research (quantitative and qualitative); therefore, they may require some adaptation in order to be applied to your field of study/research*

These tips will be split up into the different sections a research paper should consist of: abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion.

ABSTRACT

The aim of an abstract is to summarise your whole paper - it should be concise, include key-words, highlight the key points of your paper and be written last.

When I say concise, I mean concise! The abstract is what other students and researchers will read in order to decide whether your research is relevant their own work and essentially determines whether or not they’ll read on - they want to know the key details and don’t want to be overwhelmed with information.

I always aim to keep my abstracts under 250 words. I set myself this limit to stop myself waffling and dwelling on unimportant points, it helps me to be really selective of what I include and ensures I’m gripping the reader from the start.

Your abstract should discuss the research rationale, the methods and designs used, your results and the general conclusion(s) drawn. One or two sentences on each of these topics is enough.

Make sure you’re using key-words throughout your abstract as this will also help the reader decide whether your work is relevant to theirs. You can make key-words super obvious by highlighting them in a key at the bottom of your abstract (see below) or just used jargon consistently. Using key-words is also important if you’re looking to get your work published, these words will help people find your work using search engines.

Finally, write your abstract last! An abstract is a summary of your whole research paper which makes it practically impossible to write well first. After writing the rest of your paper, you will know your research inside and out and already have an idea of what key things you need to highlight in your abstract.

INTRODUCTION

For me, the introduction section is always the most intimidating to write because it’s like painting on a blank canvas - massively daunting and leaving you terrified to make a mistake!

The aim of an introduction is to provide the rationale for your research and justify why your work is essential in the field. In general, your introduction should start very broad and narrow down until you arrive at the niche that is your research question or hypothesis.

To start, you need to provide the reader with some background information and context. You should discuss the general principle of your paper and include some key pieces of research (or theoretical frameworks if relevant) that helps your reader get up to speed with the research field and where understanding currently lies. This section can be pretty lengthy, especially in psychological research, so make sure all of the information you’re including is vital as it can be pretty easy to get carried away.

This background should lead you onto the rationale. If you’ve never written a research paper before, the rationale is essentially the reason behind your own research. This could be building on previous findings so our understanding remains up to date, it could be picking up on weaknesses of other research and rectifying these issues or it could be delving into an unexplored aspect of the field! You should clearly state your rationale and this helps lead into the next section.

You should end your introduction by briefly discussing your current research. You need to state your research question or hypothesis, how you plan on investigating the question/hypothesis, the sample you plan on using and the analysis you plan to carry out. You should also mention any limitations you anticipate to crop up so you can address these in your discussion.

In psychology, references are huge in research introductions so it is important to use an accurate (and modern as possible) reference for each statement you are making. You can then use these same references in your discussion to show where your research fits into the current understanding of the topic!

METHODS

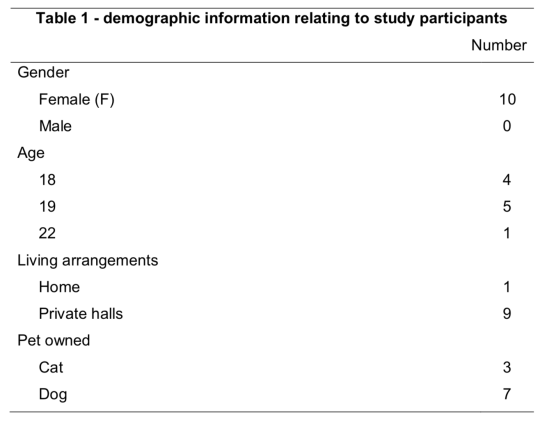

Your methods section should make use of subheadings and tables where necessary and should be written in past tense. This can make the (potentially) lengthy section easier to navigate for the reader. I usually use the following headings: participants, materials, design, procedure.

The participants section should describe the sample that took part in your research. Age, gender, nationality and other relevant demographic information should be provided as well as the sampling technique. Personally, I use a table (see below) alongside my continuous prose as an alternative way of viewing my sample population. Please note, if you’re using a table make sure it adheres to your university guidelines.

The materials section of your methods should include any equipment, resources (i.e. images, books, diagrams) or any other materials used in your data collection. You should also reference the program that helped you conduct your analysis. For example, if you are writing a qualitative research paper, you may want to include Microsoft Word in your materials if you use the program to transcribe interviews.

You should then describe the design used in your research. All variables should be identified in this paragraph, if relevant. You should also discuss whether your research is within-groups or between-groups, again only if relevant.

Last is your procedure section - the most important one! You must write this section with enough detail so that anybody could pick it up, read it and conduct the same experiment with ease. You should describe what participants were required to do, how data was collected and it should be written in chronological order! While it’s important to provide enough information, try not to overwhelm the reader with lengthy sentences and unnecessary information.

RESULTS

Your results section’s sole purpose is to provide the reader with the data from your study. It should be the second shortest section (abstract being first) in your research paper and should stick to the relevant guidelines in regards to reporting figures, tables and diagrams. Your goal is to relay results in the most objective and concise way possible.

Your results section serves to act as evidence for the claims you’ll go on to make during your discussion but you must not be biased in the results you report. You should report enough data to sufficiently justify your conclusions but must also include data that doesn’t support your original hypothesis or research question.

Reporting data is most easily done through tables and figures as they’re easy to look at and select relevant information. If you’re using tables and figures you should always make sure you’re stating effect sizes and p values and to a consistent decimal place. Illustrative tables and figures should always be followed by supporting summary text consisting of a couple of sentences relaying the key statistical findings in continuous prose.

DISCUSSION

The discussion section should take the opposite approach to your introduction! You should start discussing your own research and broaden the discussion until you’re talking about the general research field.

You should start by stating the major findings of your study and relating them back to your hypothesis or research questions. You must must must explicitly state whether you reject or accept your experimental hypothesis, if you have one. After stating your key findings you should explain the meaning, why they’re important and where they fit into the existing literature. It’s here that you should bring back the research you discussed in your introduction, you should relate your findings to the current understanding and state the new insight your research provides.

You should then state the clinical relevance of your research. Think about how your findings could be applied to real-life situations and discuss one or two practical applications.

After this, discuss the limitations of your research. Limitations could include sample size and general sample population and how this effects generalisability of findings, it could include methodological problems or research bias! These limitations will allow you to discuss how further research should be conducted. Suggest ways in which these limitations could be rectified in future research and also discuss the implications this could have on findings and conclusions drawn.

Finally, you need to give the reader a take-home message. A sentence or two to justify (again) the need for your research and how it contributes to current understanding in the field. This is the last thing your audience will read so make it punchy!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

That’s it folks! My tips for writing a kick-ass, high-grade research paper based on my personal experience. If you have any questions regarding things I’ve missed or didn’t provide enough detail of, then please just send me an ask!

Also, if any of you would like to read any of my past research papers I would be more than happy to provide you with them :-))

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the reasons men didn’t have an issue with Wonder Woman is because they can objectify her. She’s basically in a metal swimsuit. Now, I think they did a really good job with her costume considering what they had to work with. It looked like real armor and something that an Amazon woman would wear, way better than past iterations where she was literally in lingerie. Captain Marvel, on the other hand, is in a full suit that covers her entire body. It fits her well, but it’s not a skintight bodysuit like what Black Widow has worn before. It’s practical and isn’t something that men can easily objectify. They didn’t have problems with some of the feminist stuff in Wonder Woman because they were too busy staring up her skirt. Men don’t have an issue with a woman on screen if it’s someone they can objectify.

54K notes

·

View notes

Text

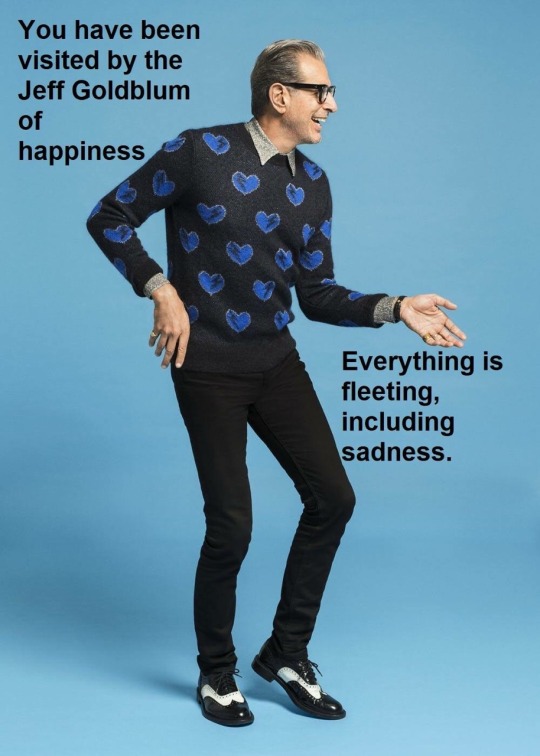

Someone I’ve known for 20+ years just posted this on my Facebook wall and I’ve never felt more seen in my entire life.

125K notes

·

View notes

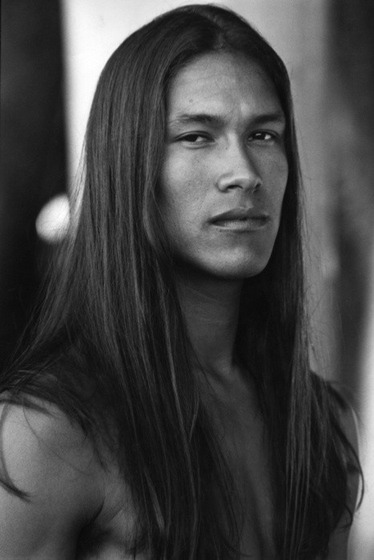

Text

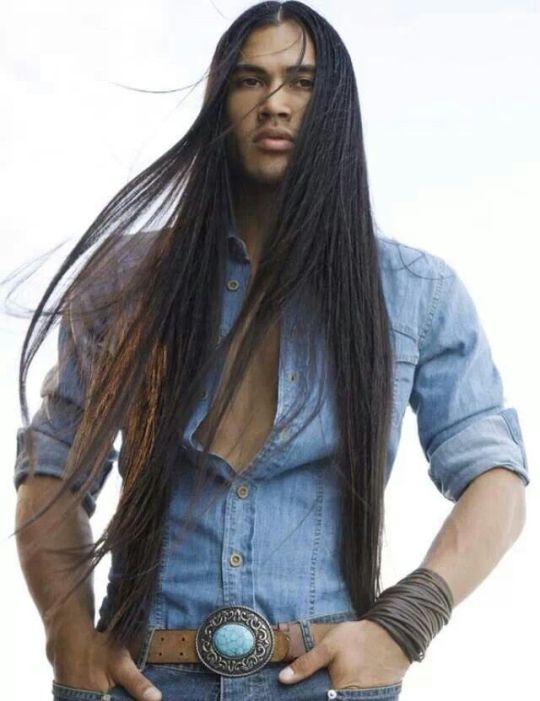

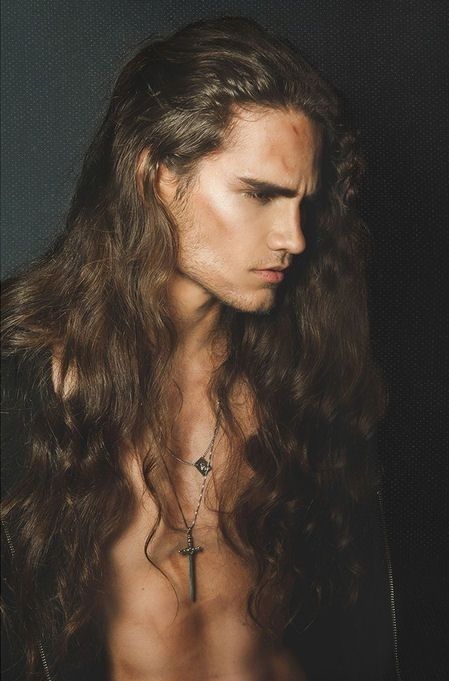

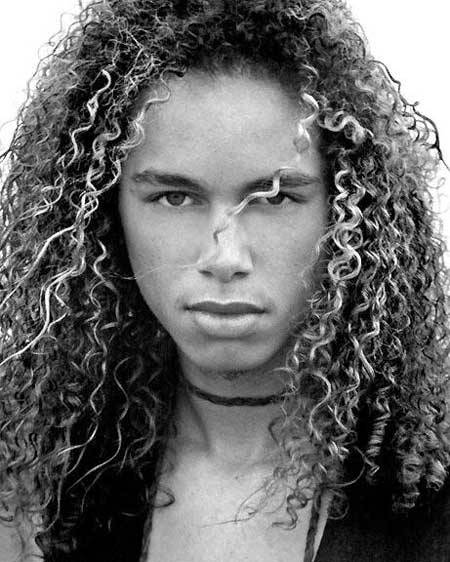

okay but

fuck your stereotypes

long hair is not “girly”

the same way short hair is not “manly”

hair has no gender

hair is just hair

&as long as you’re not disrespecting a culture with the way you do it

you keep on doing you

334K notes

·

View notes

Text

SHOUT OUT TO EVERYONE WHO STILL TRIES TO GET BACK INTO THE SWING OF THINGS AFTER DEPRESSION HIT THEM HARD. THERE ISN’T ENOUGH RECOGNITION FOR THOSE PEOPLE WHO KNOW THAT THEY’RE GOING TO LOSE INTEREST AND MOTIVATION AGAIN BUT PUSH THEMSELVES TO DO STUFF ANYWAYS. YOU ARE FIGHTING A DAILY BATTLE WITH YOUR OWN THOUGHTS AND YOU’RE STILL COMING OUT ON TOP, YOU’RE ALL BRAVE AS FUCK

1M notes

·

View notes

Text

dystopia au where we are all assigned one of two chosen genders at birth

304K notes

·

View notes

Text

i gotta say tho, readin nietzsche and platos republic while incredibly sleep deprived is kind of a whole new level of weird brain shit

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fighting Literary Figures and Philosophers

Charlotte Bronte: Please fight her, hell fight her sisters too while you're at it. Her books are so boring and I'll never forgive her for writing that fucking Jane Eyre long-winded pice of shit.

Voltaire: You could fight him but why would you want to? Hes a dapper french man who wants to separate church and state. If you do fight him make it clean because you'll kick his ass no problem.

Edgar Allan Poe: Do not fight Poe, the man is literally the embodiment of sadness. He just needs a hug and a cup of tea (just punch him a few times for marrying his cousin)

Sylvia Plath: NO NO NO NO why would you even think about fighting her?! She is literally a wonderful person who just wanted happiness.

William Shakespeare: Yes please fight him, you two can fight until dawn and you'll probably lose in the end out of exhaustion since the whole time it will probably be him giving a long-winded intro.

Nietzsche: You can fight him but he would probably kick your ass since that moustache of his gives him special powers of some shit.

Sigmund Freud: NO NO NO HELL NO DO NOT FIGHT SIGMUND FREUD!!!! Not because you could kick his ass or him yours. It's that if you could he would probably gain easier out of it thus making the entire thing awkward and unpleasent.

Oscar Wilde: Go right ahead and be my guest, he was a tall man and Irish so he would kick your ass. He also would look fashionable while doing so.

Ayn Rand: PLEASE FOR THE LOVE OF GOD FIGHT AYN RAND!!! DO I EVEN NEED TO EXPLAIN WHY?!?!

Karl Marx: fight him but watch him bring in Ingles and then they will both beat you up while telling to you free yourself from your chains or something like that.

1K notes

·

View notes