The travels & travails of two western metropolitan individuals on a permaculture inspired journey through the Americas, now back in the UK We are currently blogging at Permaculture People UK - our tour of England, Scotland and Wales

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Friends. We'll be at our "sister" site permaculturepeopleuk.tumblr.com as we begin our journey throughout the UK.

Having travelled across the Americas in a bid to obtain practical experience and a solid foundation in permaculture we came to the decision that we needed to see what was happening back home.

We're still catching up on our time in the Americas in blog la la land so we decided to begin a tandem blog focused solely on our UK tour.

The UK leg of our self steered, self guided "permaculture design course" is really the first stage of research. We hope to get a sense of the permaculture scene at home (and in a temperate climate) before beginning our own project in the years to come. Our vision: a natural self build home, off-grid, homestead, forest garden and social/educational space.

If you'd like to know where we're going and who we're meeting please do contact us:

@permapeople

www.permaculturepeopleuk.tumblr.com

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chachapoyas

The passage from Ecuador to Peru was perhaps one of the easiest and most gentle border crossings we had the pleasure of doing. Leaving from Zumba (Ecuador) we bussed it to La Balsa, the crossing, where friendly officials chatted away as they stamped our passports without a care. As evening approached and offers of a ridiculously expensive taxi to nearby San Ignacio we got chatting to a large group of Peruvian tourists who had spent the day at the river. We ended up getting mildly drunk with them and found out they were soon returning to San Ignacio. Their driver, sober, squeezed our stuff in the car as we trundled to the nearby town, pee stops on the way, a few more beers, a quick and dirty meal in town, and a lost pair of socks we were ready to travel to Chachapoyas after a nights sleep in a cheap and cheerful hotel.

[the views as we approached the border]

[the border/river between Ecuador and Peru]

According to the Oxford dictionary of place names, Chachapoyas means ‘Cloud People’ in Aymara (a major tribe of native south Americans who live in the highland of Peru and Bolivia) - a reference to the fact that the town sits high in the mountains at an altitude of over 2000 metres. Despite this the city is capital of the Amazonas Region of northern Peru. But geography and names, as we would come to learn, are not always the most accurate indication of a thing in this part of the world.

The earthen brick buildings and walls that led to the quaint centre lent the historic town a village air as we searched for a hostel where we would be comfortable for a week's worth of blog catch up without blowing the budget. Thankfully we found Aventura Backpackers Lodge, a hostel owned by Ricardo, a jovial Peruvian who worked as a tour guide for French (and English) speaking groups. An avuncular man with bright eyes and a sweet smile Ricardo and I had many interesting conversations in the reception area where the computer and sound system were. He was incredibly helpful and knowledgable and really enjoyed meeting people. We felt at home as we cooked and watched backpackers come and go.

The highlights of our stay where trips to Kuelap, an old fortress whose ruins are now grazed by llamas and quick-snap, rushed photographers, and Gocta, a perennial waterfall dropping 2,531 feet in two leaps, or stages.

Our trip to Kuelap was with a tour group, that despite our grumblings was a decision we made because we wanted to understand the archeological site and because we didn't have enough time (which we were dedicating to writing and photo organising) to plan it ourselves. Our guide, Augosto was a very impressive man. Like a peruvian version of Johnny Depp's Willy Wonka crossed with an ump lump, Augusto was a mine of information. He told us about Quechua legends as he switched from Spanish, to French and English conversing with the group as the minibus drove up the slow, windy hills.

Augosto told us of the The marvellous spatuletail hummingbird (Loddigesia mirabilis) that is endemic to Peru. He regaled us with anecdotes about ancient culture and how Chachapoyas got its name, we learnt of the celebrated battle of the condor and the bull as celebrated in the Yawar Festival, or Blood Party. The post-colonial theatre ritualising the brutal conquest of the Andes by the Spanish conquistadors. The condor, symbol of Incan mythology and the indigenous people, grapples in deadly throes, with the bull, the rapacious beast that represents the Spanish colonists. We learnt about plants and got to dip into a nearby river as everyone was eating lunch in a nearby comedor.

The site itself consists of massive exterior stone walls containing more than four hundred buildings situated on a ridge overlooking the Utcubamba Valley.

[a small tomb with ancient bones]

[a model of what the houses could have looked like]

The trip to Gocta was by our own steam and we perhaps hadn't anticipated that the walk up to the town where we paired to enter the park would be nearly as steep and as long as the walk proper. On these occasions, trekking would allow the tune of thought to match our steps as we spoke about population of humans, permaculture and possible solutions! The cloud forest trail was like sucking in green, juicy air before we arrived at the top tier waterfall and proceeded to get drenched. The falls were a local legend until their "discovery" by German Stefan Ziemendorff who compelled the Peruvian government to make it a protected area. Its splendid wash and falls runs even throughout the dry season.

Our vista lunch dried us out.

We trudged the steep path down the cloud forest, across the river and up again to the base of the second, and taller, waterfall where we passed the less intrepid visitors who were just visiting this second easier access fall.

Walking back to the small village of Gocta we saw how the land was changing from lush green to coffee and cow pastures. We had a passing conversation with a barefooted farmer who had a chemical spray back pack. We asked him about what he was doing and he politely engaged us in a brief back and forth.

We couldn't resist a river dip by the bridge outside of town before taking the long road downhill to the passing bus to return home to Chachapoyas and another round of blogging.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finca Verde - Nurse Mike

A short(ish) ride south of Vilcabamba we headed toward Nurse Mike's, our last stop in this jewel of a country. Road works had changed the picture illustrated by the directions Mike had sent us. Thankfully we were able to consult with a family who had got off the bus at the same time as us and they pointed us toward a steep and narrow footpath.

The earth path turned into thick claggy mud as we neared Mike's, the cleaving soil covering my already battered shoes. Arriving at the back entrance we walked along a path made of wooden planks and rice bags placed on the ground to counter the subsuming mud. The hillside setting in the folds of the lush Ecuadorian countryside was stunning.

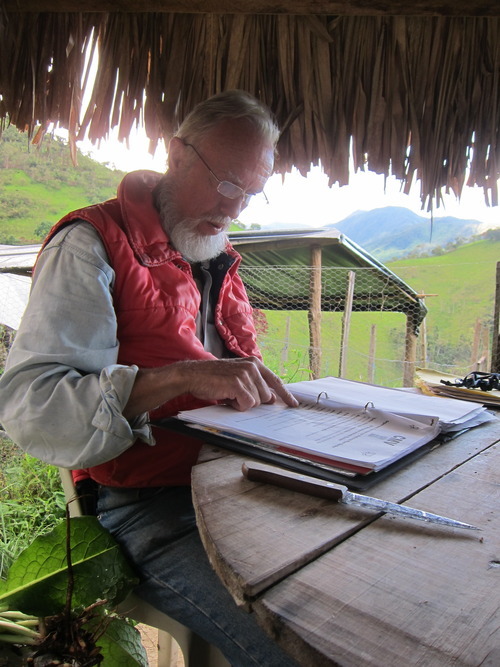

Tall with brilliant white hair and beard, and glacial blue eyes hidden behind specs, Mike had a biblical presence. After a short rest and brief introductions we were soon set to work where we met Janet from Ireland and English couple, Emma and Anthony. Weeding in the gardens we realised our shared interests and passions and all three were clearly really into this thing called permaculture.

Emma and Anthony are absolute dudes who we had the pleasure of getting to know and learning a lot from. Their moneyless voyages were an insight and inspiration into how to travel in a very different way. When we met them in late September they had travelled from north Colombia without money and since meeting them in south Ecuador they have travelled to south Patagonia and BACK to Colombia and are now literally in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean on a sailboat, England bound. Incredible.

We talked a lot about the gift economy, putting your trust into complete strangers, opening yourself up to have faith that, no matter what, there would be a place to sleep and something to eat and drink. Utterly and truly putting yourself well out of your comfort zone but being rewarded with a richness and happiness that money cannot buy. We have been brought up to repay people's favours but we have learnt that giving and taking can be more cyclical, one can receive from one person and offer to the next, with timing and monetary value being unimportant.

We learnt a lot from this intrepid duo, they gave us a lot of confidence to travel in different ways further south when our budget wouldn't allow hostels, buses and nice meals.

We also realised that we had some connections back home. Anthony and Emma met working at the New Internationalist magazine where Anthony had worked closely with Rob Norman, a close friend of my brothers and legend of Canterbury, we delighted in the coincidence as we stepped down the muddy path to the main section of the grounds.

I would thoroughly recommend checking out their blog here.

Our first afternoon and Mike had promised us his 'Comfrey 101' course. A plant forever associated in my mind with Engurland, we were given the low down on this versatile herb. The widely travelled cross hybrid comfrey Symphytum × uplandicum (as referenced in the masterful 'Edible Forest Gardens') is a potent fertiliser and medicinal. A perennial herb (top permaculture points) in the Boraginaceae family, the broad hairy leaves and nodding cluster of small brilliant purple/blue/white flowers are a favourite of the bee. Native to Europe it enjoys damp and grassy grounds. Known as a dynamic accumulator the plant "mines" nutrients from the soil which then find their way into the prolific leaves and then the top soil. Soft and lacking any serious fibre the leaves break down quickly making them ideal for "chop n' drop" mulch, compost tea, or vital additions to compost heaps giving that pile of goodness a nitrogen fix (excuse the permaculture placed nerdy pun). Its healing properties are well known, one of its given common names "bone-set" suggesting why. Modern uses of Comfrey as a herb tend to be strictly topical - that is, pertaining to the surface of the body - and so used as a skin treatment. Some use the leaves like spinach in meals but there is evidence that they contain alkaloids that can cause liver damage hence warnings not to eat it.

[chickens enjoy comfrey too]

[Mike applying a comfrey poultice to a scrape on Anthony's neck]

Check out this video illustrating why Comfrey is a pin-up permaculture plant.

One evening after Mike invited us to his ten breathes meditation routine after dinner I caught a glimpse of something out of the corner of my eye. A brilliant orange and large comet-like object in the sky to the north appeared to move toward the earth. It was travelling slowly. Time enough to get everyone's attention and for us to all stare. For a brief, horrifying moment I fancied that the world was going to flash up and everything was going to end. I remember the feeling as the beat, in the instance of my thought, skipped my heart. The comet continued behind a mountain and to god knows where. The comet, which we later learned from one of Mike's friend who he phoned, is called a fire ball. According to the The International Astronomical Union a fireball is "a meteor brighter than any of the planets" and bright it was.

Work consisted of a varied mix of active and more relaxed tasks. Clearing the duck pond, hauling compost up and down the steep steps, composting, building and stringing trellises, machete-ing, comfrey collection and cutting, harvesting peas, transplanting peanuts and of course, weeding. Walking up and down the steps alongside the neat rows of beds that are fenced off, I noticed how a section of steps would veer off into a new path on the bank, and then rejoin the built in wooden steps a little further down. The grass bank reclaiming the steps, it struck me how easy it is to overlook things. The idea of history, from an ecological perspective, is not very present in our minds. It's easy for the path of the past to be occluded by current events. I was reminded of the concept of the 'shifting baseline' an idea employed by some ecologists. The name refers to the shift, over time, of what a healthy ecosystem is remembered as. Generationally speaking what implications does a shifting baseline in the natural world (e.g. biodiversity and carrying capacity) have when as a wider society we aren't ecologically literate. Historical ecology attempts to address these questions looking at relationships between groups of people and their environment over long periods of time. I was reminded of the word Christopher Nesbitt's spoke when we were sat with him in his corn field surrounded by ancient Mayan ruins. Was the collapse of the Mayan civilisation due to an unforeseen environmental disaster prompted by mismanagement and myopia? Having recently watched Ken Loach's excellent film 'The Spirit of '45' about the history of our blessed NHS I appreciated the thought that in our fast paced, pop culture world we often take the ahistorical view of the present as the end and beginning of all things.

[coffee 'cherries' being skinned]

We were all staying at the bunk house and I noticed that the compost bucket loo area was overgrow. Sat with a view to pooh to I was the only one up as the others were still sleeping. The abiding sound of the nearby waterfall and the flitting diving swallows that carved the air with their wings seemed to be the only movement in the still morning where mountain ranges stood timelessly against the ever changing sky. Permaculture, I had come to appreciate, is hard work. Two ideas that are often implicit within people's understanding of permaculture when we chat to them is that it means you can all of sudden grow anything, and that permaculture is "easy". As a design system permaculture is about directing energies in the most economical and least harmful way. Intelligently designed landscapes require work and planning and being out there, whether farming or gardening, it is physical. In this sense permaculture is hard work. An observation that I'm glad I have arrived at.

The basic wood structures, cups and tools marked with numbers, the u.s. army desert boots under a pile of boxes and books, the bunker (perhaps i shouldn't be saying that bit) and the five gallon bucket compost loos gave the appearance of functional frugality. Light on aesthetics, and rugged enough to weather constant usage, lent the farm a boot camp kind of feel. Perhaps that feeling was toned by Mike's story of his time as a vietnam wartime nurse that he shared with us. A loving and generous spirited man Mike enjoyed the company of the many people that passed through his farm.

During our stay it was time for the sugar cane processing. The local workers rising with the sun to start the laborious process of putting the freshly cut cane through a juicer, filtering the juice, cooking it for hours and hours until a thick syrup then pouring it into moulds to dry as the naturally delicious sugar loaf 'panella'. The whole thing smelt divine.

[cane being fed through the machine run by a very loud generator]

[the left over dry fibre of the cane]

[juice running through series of troughs]

[the final trough for juice underneath which a continuous fire it stoked to cook the juice]

[the final pouring into moulds, this stuff is seriously addictive]

We ate very well and we enjoyed cooking. Mike was gracious enough to allow us to experiment and he enjoyed the meals we prepared and shared. With his comfrey course in mind I was excited to bring together my first 'permaculture people pesto' part inspired by my medicinal travel kit of garlic, ginger and turmeric. Ingredients: garlic, mustard leaf (two types), peas, rosemary, salt, pepper, gotu kola, sesame see, linseed, olive oil. Food after all is medicine.

[the low tech food dryer used for herbs and emma's delicious bread rising]

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vilcabamba

From the watery highs of Cuenca and Cajas National Park our next stop was the heralded hippy haunt of Vilcabamba in the south of Ecuador.

An agreeable climate set in a scenic valley Vilcabamba is fabled for its long lived residents. Referred to as the Valley of Longevity, tourists as well as new agers have descended on this otherwise quiet place in such of the elixir of youth. The name Vilcabamba is said to be a combination of the Quecha words "huilco", a sacred tree (Anadenanthera colubrina) common to the area, and "bamba", meaning plain or lands.

A prosperous place with a french bakery, sacred dance classes and numerous hostels we sought the Rumi Wilco nature reserve and ecolodge that our friend Monika from Rhiannon Community had told us about. I was intrigued to see how such a place would compare with Rio Muchacho. As their website states in that charming off-tilt yet somehow poetic "incorrect" English, "Earth travellers, no longer mere passive tourists - unaware and unconcerned passersby - become instead doubly satisfied, with their active partaking in the welfare of the regions she/he is temporarily enjoying."

Started by Argentine conservationist couple Orlando and Alicia, Rumi Wilco worked to ensure the preservation of a 40 hectare tract of land that combines the lodge grounds and neighbouring properties. Support for their bid arrived in 2000 when the government awarded a protection status to the demarcated land and initial funding was given. Wood and adobe houses now sit beside the reserve, aback a little from the stream, where a self guided trail runs up and along the ridge looking over to the other side of the valley. Once again, from Rumi Wilco's webite: "In our view, this [desertification] is due to the insignificant value ecosystems attain within our actual economy. So low a value in fact, that peasants opt for burning the immensely complex and diverse nature they own, only to hurry a few years' crops before the land loses its fertility for just about everything except grasses and thorny scrub. A few cows, donkeys and horses become the final users of these now barren, steep mountains. And only during 3 or 4 months per year, while the rains last. This predicament now threatens to eliminate the last 8 to 10 percent of natural ecosystem remaining in the province of Loja, much of which is weakly protected by the National Park status of Podocarpus (the name applies to the only Andean genus of native conifer trees of Ecuador -a relic from the ancient past). It is, therefore, of imperative necessity that alternate models be implemented whose top priority would be to stop the burning and any other form of environmental degradation, by means of valuation - also in monetary terms - of our Natural Heritage."

I quote this at length because it's important for us to not pretend we know what we are talking about or assume, with our western privileged eyes, that what we see is as it appears. Back to valuing nature monetarily I agree completely with the necessity - and urgency - of assigning a value to our natural world so that we can all enjoy and prosper the earth in an equitable fashion. I was reminded of the The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) study that aims to highlight the economic worth of biodiversity. I need to read more about the idea as my initial unchecked, and admittedly unreasoned, reaction is that placing a price tag on nature is open to all kinds of abuse. We live in a world awash with finance, money often the only currency of understanding. We live too in the natural world, where in one way or another ecosystems, and the attendant biodiversity, has, and 'is' the basis of our economics. It's not just a question of balance. The permaculture ethics of fair shares, earth care and people care are a dynamic matrix from which wise and rational decisions can be made about managing resources and ensuring that there is enough for all.

We enjoyed sharing our understanding of permaculture to some fellow long terms 'earth travellers' at Rumi Wilco, newly weds Lucy and Elad originally from Poland and Israel but residing in Kent, and Yvonne from Switzerland. It is always a good challenge to communicate to others what one feels passionately about!

You can check out Lucy and Elad's travels at their blog here

With this is mind we made the visit to Podocarpus National Park. Walking up the steep winding roads to the lower montaine forest, it was clear that, despite being within the park ground, the effects of farming and deforestation where keenly felt. Clumps of trees clung to the side of steep mountains as all around forests where broken into a mosaic of cattle pasture. Cloud forest veterans we enjoyed the walk very much delighting in the unassuming yet beautiful flowers of the páramo tufted top - the "high, tropical, montaine vegetation above the continuous timberline" as defined by some ecologists. The park, named after the sole Andean genus of the native conifer tree. Returning to the park's entrance we were lucky enough to see a grey fox that one of the workers later told us often loiters near the guard's homes scavenging.

Another fleeting visit, another ecosystem or two, the sweep and breadth of our travels were becoming increasingly inspiring and thought provoking.

To find out more about Podocarpus National Park click here and for Rumi Wilco click here

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cuenca and Parque Nacional Cajas

From the countryside to the city we were thrust into the groovy bosom of Cuenca. Lauren's birthday happened to work out with our stay in the student town and UNESCO World Heritage Site.

We found a lovely hostel next to a book shop just in the centre where we enjoyed a beautiful homemade breakfast. A walk away from the river that runs through the city we were able to explore and delight in the market squares, street graff and hip bars. We packed in museums and sight seeing on a beautiful September day delighting in birthday ice-cream.

[the local museums were fascinating with displays of the ancient practice of head shrinking!]

[party at the end of the bridge]

For the evening we returned to a bar that we saw had a capoeira class. I couldn't help but join in. Sat watching the tables it was clear we were in another Ecuador. Smart phones in hand, a meeting huddled around a new mac laptop on one table, fancy beer behind the bar, and music blaring out it was more like London than Logroño. A world away from what we had been doing. Travelling can propel mind and body into a collision of realities of which we would enter and leave just like that.

What would be a Lauren and Phil weekend away if it didn't include a walk. A mere 30km up into the Ecuadorian highlands, we travelled to Cajas National Parl (CNP) with our new friend, Amalia, from Spain staying at the same hostel. With one of the highest densities of lakes in the world, Cajas was all about the waters. The cold humid climate of the mountain ecosystem in the southern Ecuadorian Andes contains cloud forest, evergreen high mountain forest, and high grassland - the park's most typical plant community. The high grassland cover acts as a cushion. The cool weather and low atmospheric pressure combining with the spongey soils allows for high water retention and water regulation/relinquishments cycles. CNP produces over 60 per cent of the water consumed in Cuenca and its surrounding town.

Drinking from the many streams and rivers that feed the park's 167 lakes and 807 bodies of water we were smitten. We dipped naked in the glacially cool waters drying ourselves under the sun. The vital yet mysterious combination of two hydrogen atoms and one atom of oxygen is fundamental to our existence. Understanding that we too are composed of these same elements is part of our dignity - and humility. Our journey through the Americas had been a communion with water and Cajas National Park was a recognition and celebration of this understanding.

Walking through grassland and descending steep slopes through cloud forest we passed the Quinua tree (paper tree), part of the Polylepis ("many scales") genus made of twenty eight recognised shrub and tree species endemic to the high Andes. The papery, rufescent peely bark characterises the tree that often forms strange contortions and close canopies (as a result of the winds and cold) lending Quinua tree woods an enchanted forest feel.

Climbing down the mountain the rush and gurgle of the parallel stream was so tantazling that we had to dip in again forgetting almost how cold the clear waters were. The generous sun filled the late afternoon as families and fishermen were returning from their walk around one of the low lakes to return home. After 8 hours walking we were full of fresh air and clean water and ready to keep moving south.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finca Logroño

Finca Logroño was to be our first WWOOFing experience for some time. Excited about the prospect of getting to live and work with an Ecuadorian family, we were picked up by Rene who took us to his family home and 9 hectare (22 acre) farm on the outskirts of Logroño, the town that bears the same name.

[the plaza of Logroño]

Tucked away at the end of a long drive the large house had kids and dogs waiting for us. Behind the building and falling down into a bowl was the main stretch of land that included fields of bananas, yucca, and secondary growth forest. It was clear there was a lot going on. Our room, small and simple was tucked into the corner under the roof on the upper floor. Outside were bags of rice and piles of corn as well toys, trinkets and shoes.

It was clear that mixed with the natural abundance was the proliferation of junk. Prams, food wrapping, plastics, old tyres, and tins were strewn across the drive outside the house. It was hard not letting my immediate judgement baulk at such a scene. The house was visibly dirty and the first notion that came to mind was that it couldn't be healthy for the family. After one evening meal of the staple rice and lentils, I was doing the washing up and picked up a few pieces of plastic that were on the floor. Rosa, mum of seven children and Rene's wife, her eyes belying a sadness so deep that seemed to stretch back long ago, asked me if i found their home ugly. How could I respond? I did. I freely chose to help with washing up as she worked to feed her family and us. I somehow evaded the question and continued.

We were strangers unto one another. Despite this I had to remind myself that hear was a family that had allowed us into their lives and shared their table with us. We would all eat breakfast before the kids went to school and share evening meals around the cramped wooden table in the corner of the main living room that doubled as the kitchen. On some occasions, if the children weren't engrossed by the small TV in the next door room where four slept to a bed, I would help Solomon or Elias, two of the boys, with their English homework. The children would add heaps of sugar to their water some of them having badly decaying teeth. With the abundant sugar cane around, which, admittedly, needs processing, a tradition of drinking 'jugo de cana' had been replaced by adding packaged white sugar.

Ostensibly Finca Logroño has it all. Land, crops, animals, and water. One afternoon we were harvesting, cleaning and cooking nampi, a tuber, very much like potato, which is highly nutritious and grows very easily. This was for feeding the pigs that they kept near the house in simple pens. It struck me that a lot of energy was used to feed a pig that was housed, rather than left to root and scrabble around in a larger fenced area. The abundant nampi could go directly to the humans? We spoke about this, and Lauren, in her wisdom, made the observation that although having all the necessary elements, the design was missing. To be clear, we weren't dismissing their practice off hand as we have no idea about running a farm in a tropical climate. Our observation was simply exploring how the farm might look from a permaculture perspective.

Alongside feeding the pigs nampi, banana leaves and sugar cane, we helped clear some paths, harvest yucca and did plenty of corn shucking. Many idle moments were spent as Rene went about his business coming and going. Rosa, shy, and untalkative would never readily ask for help but when she was out in the gardens or on the grounds we lent a hand. As the week progressed it became clear that it was much stranger than we had thought.

[Harvesting yucca]

[Cooking ñampi to feed the pigs with friend and employee Irena]

One day Rene encouraged us to go and visit some cows of his he was planning to sell. After a thirty minute drive to where the road ended by a bridge over a beautiful little stream, we trudged for forty minutes to a very remote house where Rene's brother lived part time looking after cattle and sheep. In toe, were two guys from a nearby village interested in buying some cows. Rene took us to where the cows grazed. Discussions about prices and logistics went back and forth as a decision was finally made. This was all happening in a fenced off field with dozens of cows whose curiosity was piqued by our presence. The walk back involved chasing and cajoling the chosen cows as we tried to keep them on the same path. Perhaps most bizarrely of all was the attempt to load two humungous ruminants onto the back of Rene's tied together pickup along with eight people. In the end they were taken one at a time with a few people hanging back to wait with the other cow for the second lift.

[Above - Rene waiting for our lunch to be ready in the family hut in the hills where the cattle are kept. Below - friends and neighbours helping for the day]

[Rene's brother]

[the natural surroundings were beautiful]

The grandfather (Rene's father) was a taciturn and thankless man and we often saw him ambling off in the mornings with a jet pack, applying pesticides to the rice plantations. At meal times he would occasionally talk with Don Segundo, an employee who lived in a house of theirs across the main road and who on occasion would not be seen for days after a drinking binge. We didn't really get to know him but we were told he had left his family to seek work and found Finca Logroño. One afternoon I saw him sat outside his house as the rain crashed onto the tin roof. His left hand listlessly fallen by his side, head slumped, the beating rain stirred him from his slumber. We never got a chance to say goodbye to him as he went on one of his benders before we left and Rosa hadn't heard from him.

One evening Rene told us something extraordinary. He didn't believe in evolution and cited various examples of miracles that had happened to him proving a supernatural god's existence. He talked cryptically about god and catholicism and how the man of the house was to work while the woman's role was to stay at home and look after the children. He spoke how Ecuadorian culture, especially campesino culture, is very machismo. Our conversation became more strained as we felt Rene would be telling us, rather than talking to us. One evening washing up, I noticed a photo of a younger Rene, with leather jacket and smile, posing beside a fountain that I could only assume was New York and I thought it very strange that a seemingly travelled and educated man was talking to us in such a way.

Running a house, looking after six children (the eldest Diego was studying in the nearest city), working with cattle, employees and trying to sell crops is no easy task. We had a reality check. Our ideas are to run a small homestead. We have never been under the illusion of wanting to grow all our own food and meet our nutritional requirements throughout the year. But seeing how the family lived we both strongly felt that whatever it is that we want to do, we want to do it with meaning and enjoyment. We had seen that it was possible, so what made Finca Logroño different? Another telling moment was when Rosa had said that they were very poor. I wondered how she defined this and what such a concept meant to her as both an idea and a reality. We had seen how they were able to buy things for the children. The trail of rubbish told a story of money spent. It wasn't simply a case of being cash poor, but it was something else. Poverty of mind and poverty of aspiration were notions that came to me. Who was I to say one way or the other? How did my own culture and upbringing inform my perspective. We had met many Ecuadorians, spent time with a family at Finca Mono Verde, and the day we arrived to Logrono town we were sat in a cafe having eaten a nice lunch, checking our emails on wifi, talking to the family who owned the place about their move back from Canada. It seemed to me that there was something else going on. A culture of poverty, rather than actually being poor. Perhaps by the level of material comfort and wealth enjoyed by a post-industrial modern society, Rosa and her family would be deemed poor. Their eldest soon, Diego, 19, was at home for a weekend visit from university, the first of the family ever to go. Rene, had travelled and worked in New York. It was something else that we were not privy to that seemed to be going on.

A huge factor in our permaculture peregrinations is that choices can be made. For us permaculture means a life of abundance. An abundance of experience, a wealth of ideas, a richness of feeling and being. Very idealistic but what are we if we can't dream. Are we simply going to be tethered to the land, or our desks or our fears and preconceived ideas? In Mollison's weighty tome, A Designers' Manual he writes how a move away from dull oppressive work and mechanised overcomplexity can be realised. Permaculture aims to reduce unrewarding work and drudgery. By no means an answer, Permaculture is more subtle than that. By asking questions, and making observations, permaculture has helped us to navigate our realities as we work to make it happen, but has this perspective and ambition only come to us through our privileged education and worldly travels? We live in a very different reality to Rene, Rosa and their children.

During our stay we visited a local Community, where a strapping young Shuar got into his traditional garb and invited us to a personalised ceremony at the a waterfall where he told us about the Shuar culture and their reverence for water. After, we spoke in the community hut where they sell trinkets and crafts. Like most villages, they are dependent of subsistence agriculture but with tourism they have clubbed together as a community to organise events, tours and, we hope in not too tacky a way to preserve their traditions.

Perhaps one of the scariest things was going caving with one of the start up tour guides listed on the local community board in the re-vamped, beautified Logroño Square. It was all a bit touch and go as we had to find out if caving was possible or not due to far off rains that would affect the water levels inside the Caverna de las Cascadas. His young, fearful face didn't instill me with any confidence as we clambered up rocks and through narrow passes with exacting foot precision to reach the waterfall that dropped into the cave from the outside world. It was thoroughly exhilarating and the young chap proved he knew how to safely get people to the waterfall despite his inability to exude confidence.

To relax our racked nerves and warm our cooled bodies we finished the day out with a visit to the natural hot springs, next to the beautiful Rio Upano. A small sandy paddling pool, a stone's throw from the strong, cool currents of the river are pleasingly warmed by the volcanic heated waters that are coming straight up from the ground. In the softer parts of the natural pool, you could stuff your leg down a quicksand type hole feeling the temperature rise as your toes would be tickled by the bubbling pressured water. Heaven!

[Lauren's shoes left behind after their last outing in the caves, they served her well]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baños de Agua Santa

Nestled in the verdant foothills of the Tungurahua volcano, Baños de Agua Santa is famed for the thermal springs that give the town its name. Baños, as it is popularly known, ambles along in the shadow of the active Tungurahua volcano that last erupted in 1999.

We were there for some R&R after all the hard walking and thinking we had been doing. We cozied up to locals and tourists as we splashed about in the most appetizing of the town’s thermal baths, the Piscinas de la Virgen. Open in the evenings, the whole town descends on the most sought after thermal baths hopping from hot to cool. The larger of the upper outdoor pools sits below a waterfall that is dramatically lit from below for the evening crowd.

We enjoyed the fancy food culture in the day and the colourful street art as we ate our way around some fine eateries and some not so fine but more charming market food.

Our customary walk was a hike to the Casa del Arbol which was sadly closed. Our view of the volcano was obscured by clouds. Before leaving we did, however, catch a brief glimpse of Carlos, the resident volcanologist who we had heard about in town. Like a seemingly reluctant yet obliging caretaker, Carlos, has been living in a rickety looking wooden house just next to the Casa del Arbol for 30 years. Tasked with keeping an eye on any activity from El Volcan as it’s known locally, our brief interaction gave me the sense that here was a man who bore on his shoulders the burden of potentially catastrophic news, while tending to sensitive volcano reading equipment stored in his home, while tourists and townsfolk went about their business. Either that, or he was in a particularly bad mood as we had heard he often gives people a tour of his house.

Touristy as it was we couldn’t not go. To our relief it wasn’t just a grimy backpackers destination but a place where Ecuadorians went. A pilgrimage site for many, the Church of the Virgin of the Holy Water, Nuestra Señora del Agua Santa, where the town gets its name is said to be a site where miracles have occurred.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Puerto Lopez - Parque Nacional Machalilla

The humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) is the star of the show in this otherwise sedate seaside town. The numbers of humans swell from mid June to October when its whale watching time.

We had to see thess famously curious mammals that we heard would sea saunter to boat loads of puny humans. As usual we did our homework before choosing a tour operator, who, ten a penny, throng the main strip along the sea front.

What can we say. I've never seen anything so big. A young male drew close and began showing off, drawing ohhs and ahhs as we all snapped and had our fingers poised and eyes sharp for the next sighting. Humpback whales display what is known as breaching behaviour which includes such dynamic sounding displays as spyhopping, lob-tailing, tail-slapping and peduncle throws.

Our young male indeed gave us a show. Sadly, it was on one occasion that it was clear for all to see that his tail was ensnared in a fishing net. According to WWF research cited by the Cetacean Bycatch Resource Centre, "More whales, dolphins and porpoises die every year by getting entangled in fishing gear than from any other cause." A sad reality, entanglement poses a mortal threat to these gentle giants of the sea.

As well as the breeding Humpbacks that come to Machalilla National Park's waters, the protected area incorporates a diversity of habitats. A spattering of islands including the big two, Salango and Isla de la Plata "Silver Island", famed for the supposed silver that was hoarded and left by Sir Francis Drake, also known as the "poor man's Galapagos". Los Frailes beach, a beautiful stretch of sand and sea, and dry forest nearer the coast and cloud forest further inland.

We decided to hike to Los Frailes beach through the forest. The seemingly still forest was a whisp of its wetter self, trees and plants baring all in a bid to beat the pounding sun. Hotfooting to a spectacular mirador that looked over the crescent shaped stretch of Los Frailes and into the ocean we passed a stretch of the Palo Santo tree, its heady fragrance unmistakable. "Holy wood", Palo Santo (Bursera graveolens) has been used by cultures throughout the history of south America. Its pungent, thick smell alludes to its potent properties. Used by pre-Incans and Incans for rituals of purification, the burnt wood, is often found being sold next to churches in the cities as an incense. It is also reputed to be an effective Mosquito deterrent.

The walk, despite the lack of shade was punctuated with sea dip pit stops. As we were perhaps the only people walking without a personal vehicle we managed to hitch a ride with a tourist bus of local Ecuadorians back to the main road. We then waited for a ride (on a motorbike) to the village of Agua Blanca, a small community descended from the Manteño people, where a small municipal museum houses artefacts and tools of the pre-Incan culture. The incongruously named Agua Blanca, set in the dry tropical forest, is also famed for the sulphur-water hot pool which relaxed our muscles after the hot walk.

[No photos as camera battery died!]

It was interesting to see how a National Park, busy with people "consuming" nature, managed its resources. Of course, we didn't have the full picture, but we got a sense that the park, created in 1979, is a stressed place. Despite the dryness, the park, was named as an internationally important site under the Ramsar Convention, an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable utilisation of wetlands - perhaps one of the world's most important yet misunderstood ecosystems. The Machalilla National Park has attracted the support, and funds, of the Parks in Peril program (http://www.parksinperil.org/) as illegal fishing, deforestation, and tourism strain and overwork the park.

With this is mind we were very conscious of how our enjoyment of the park was contributing to the double edged sword of giving and taking. We often wonder, how could permaculture inform conservation strategies? What would they look like? How would an understanding of permaculture help conserve and contribute to a fairer, cleaner and healthier park for all? A whirlwind naturalist weekend, we were humbled by the sheer magnificence of the Humpback.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rio Muchacho

Canoa, a small fishing village on the Pacific coast known for its surf and itinerant artisans, is also home to the office and operations team of Rio Muchacho, an 11 hectare (27 acres) sustainable farm, agro-tourism and education centre.

We spent the afternoon and evening in Canoa strolling the traveller thronged beach front sampling the street food and exchanging words with stall holders and hawkers.

With our continuing forage into permaculture in practice it was time to get our mind mulch and see what good large scale land practice informed by permaculture design looked like in a dry/transition forest climate.

Driven to the site along dirt tracks passing farms with bare fields churned up by the corralled cows and cut trees, it was clear that the once verdant Ecuadorian coast was stressed under clear cutting for cash crops.

Rio Muchacho began life in 1990 when New Zealand horticulturist Nicola, and Ecuadorian environmentalist husband Dario (who we sadly didn’t get to meet) worked to show that another way was possible. Through reforestation and permaculture inspired design the land had been transformed. Noticing the shade offered by the trees and greenery it was immediately apparent how much cooler and varied the Rio Muchacho grounds were compared to their neighbours.

We started off with a delicious lunch part picked from the gardens and otherwise locally sourced. The beautiful spoons and cups were made from site grown calabashes (also known as bottle gourd, long melon and mate in some places, the mature fruits of this vine are used for making utensils) alongside locally handmade ceramic bowls lent the meal not just an aesthetic twang but a different flavour.

The tour began with one of the on site workers taking us to the beautiful gardens at the foot of the house. Nicola, with kids on hip and in tow, soon took over and walked us through the impressive array of systems they have in place.

[guinea pig beds over a veg bed]

[worm beds underneath the palm fronds on the left]

[a delicious bread fruit to be served for dinner]

[a solar dryer for herbs, seeds and fruits, above and below]

Pigs, cows, guinea pigs and worms the animal systems, although looking a little tired were managed in a way that resources such as manures where used for biogas and as a fertilizer. Perhaps most inspiring were the large gardens which were bursting with life. An ardent horticulturist Nicola was clearly most enthused and energised when talking plants.

[the unripe fruit of the sacha inchi vine which produces a delicious nut rich in the omegas, a new superfood]

[The loofah plant, the fruit once dried is used to bathe with]

[the annual garden beds]

Reforestation had begun about 30 years ago but as Nicola told us, working to plant trees in a wet/dry climate was not so easy – especially in a tropical climate on ruined ground. Regardless, their efforts have led to reforestation work in the community.

Privately owned, the farm is a beacon of environmental stewardship. Our visit came at a good time as we had become increasingly aware of the physical damage cattle and conventional farming can do, seeing it, rather than knowing it abstractly. The aim of the farm, as Nicola told us on our tour was to act as a model.

Alongside demonstrating a combination of techniques and technologies, Rio Muchacho prides itself on its education. Running a number of adult education course perhaps most important and proudly, the Rio Muchacho Environmental School works to educate children in an area lacking in resources and time for such pursuits. The school curriculum is built around environmental education. Rio Muchacho regconises that to change inset practices can’t just come around by doing it differently but by showing and incorporating that change in the lives of locals.

And what better way to celebrate the majesty of trees by getting up close and personal. We were taken to a grand old strangler fig tree made for climbing.

[The Blue-crowned Motmot (Momotus momota)]

We have been incredibly fortunate to have visited so many projects. An education in the making as we learn more and more we often reflect on the sustainability of such projects from a human and social perspective. Seeing how, and why, things are done has helped inform our own ideas and aspirations. Listening to people's struggles, preoccupations, dreams, and ideals is instructive and goes toward framing our own future. We are immensely grateful to those people that combine their work with conservation and education in an open way.

Despite our brief day visit we drew alot from Rio Muchacho and the work they do.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finca Mono Verde

Ecuador is a biologically rich and diverse land. From the Amazonian interior in the east our next stop was on the north western coast to visit Finca Mona Verde (FMV), a 22 acre ecological farm. Nestled in the sweeping tropical dry forest hills of Tabuga in the Manabi province, from one end of the site you can see the Pacific Ocean and lime and banana groves as you turn and descend toward the other end.

We were told about FMV from a young chap we had met in Colombia. A WWOOFing site, we knew that FMV was up to some good stuff so we had to make the trip. In 2010 three friends purchased the land. Soon after one of the founders, Andrea, met with Monica and Arnaud who are the resident family, caretakers and permaculture bad asses. With baby Mael, they were perhaps the most beautiful family we had the pleasure of meeting.

The land before and after FMV was set up.

The day's activities were varied and there was time for reading, cooking and plenty of conversing.

[we ate very well]

[the best chocolate brownie ever from Mindo's finest chocolate factory]

We shared the table with three other volunteers. Patrick, a returning volunteer and friend of Monica and Arnaud's, is an intelligent and sensitive phD student, and yoga instructor, researching organic farming practices. Natalie, a young thoughtful undergrad from California was finishing up her degree, and Ben, the stoic, hard working French mundivagant was tripping the world.

[Mael, Monica, Arnaud, Patrick, Natalie and Lauren]

[Ben working hard building new steps up to Monica and Arnaud's house]

Monica, a Quitena, was a strident yet caring person who was confident in her opinion. Having quit a 9 to 5 change the world office job she began to learn about permaculture and was headed for a lifestyle reset. Super smart with a no nonsense approach it was clear that what she was doing was a radical departure from her past and her family's idea of making it good. She made a memorable quip about how things began to make sense to her searching and questioning mind with the introduction of permaculture into her life. The psychic rupture characterised by the marked difference between her life pre and post permaculture, when most things began to make sense. The turning point and ensuing discovery a sentiment we very much share and are learning about ourselves.

[Monica and Arnaud]

Arnaud, her French husband, a straggly Breton who had travelled through the Americas before meeting Monica was to become lovingly known as the Perminator. A self-confessed perma-nerd, Arnaud was really into it. He worked super hard and was always having ideas. He was also a very funny man who enjoyed playing his cello, harking back to his days on the road making money as an itinerant musician and performer with a couple of friends.

And from the union of two permaculturists came Mael, a beautiful boy. It was an utter marvel to watch him exploring, playing, touching and staring at his natural surroundings. Lauren and I reflected on how this education was incredibly special to a young mind that was stimulated and responding to its environment. Lauren would comment how Mael would exercise an intrinsic caution and curiosity that steered his natural explorations. An absolute cutey he wasn't immune from the odd table tantrum at dinner time. His name, Mael, in Breton, the celtic language of Britanny, means “chief or prince.”

Work included harvesting velvet bean and jack bean, clearing areas for growing, tending the gardens, building compost, mulching the coffee, fixing stuff, digging stuff and over a three day marathon moving a mahoosive mound of bokashi – a Japanese method of turbo composting. Housed under the house, the huge medley of forest soil, rice husks, chopped up banana leaves, chicken shit, molasses and EM (effective microorganisms) had to be turned and mixed twice a day. A massive job that was helped to the tune of loud music. Bokashi is a fermenting process that makes quick turnaround and odourless compost. As an anaerobic process fermentation only happened in the unexposed mass of the pile and the turning would allow every particle to ferment equally. The finished product would be applied to the thin tropical topsoil to boost fertility ready for plantings.

Other jobs included finishing the natural build shower. The plaster made up of finely sifted sand, clay, wheat paste, linseed oil, and fermented cow shit – a recipe Arnaud had learnt during his time at CIDEP, in Argentina during his travels. Natalie artfully applied the same finish to the beautifully designed cob oven.

One task involved the irregular collection of dried leaves that would carpet the seasonal stream at the foot of the property. Their neighbours interestingly would, along with the waste created from plastics and other materials, sweep the leaves from their property down to the dry stream bed. Arnaud very much saw one man's waste as another man's gold recognising the richness of a resource that would otherwise be swept away or often burnt. We collected the leaf mulch by the truck load and put it to good use.

One day I lost my leatherman in the velvet bean field on the rare occasion I had placed the tool in my pocket rather than returning it to its pouch. The ground thickly coarsing with clumping grasses, vines, and all kinds of plants, was, as Monica said, like a black hole, eating up anything that was forgotten or dropped. I was distraught. After I made Patrick and Natalie scour the ground with me. I kept returning with Lauren to the area I knew I had dropped it (I had been for a pee and for some reason I decided to let my trousers fall down in the moment of rapid relief. I suppose it was then that the knife had slipped from pocket into the grassy void). Set jawed I was determined. I couldn't lose, after the iphone, what perhaps was my most valued and used tool. It had been days and I knew I had to find. Returning to the spot I saw a silvery glint and yelped and hopped all the way back up the drive to the house shouting my victory.

Finca Mono Verde uses its sloping inclines and steep trajectories to its best effect growing a wide variety of crops. Plants and tree include coffee, cacao, pineapple, plantain, bananas, velvet bean, jack beans, greens of all shades and sizes in the greenhouse, courgettes, aubergines, tomatoes, passion fruit, air potato, chayote, mangos and much more.

On one occasion Monica and Arnaud invited us all for an overnight trip to a seed swap and storytelling shindig that was really a knees up for the locals. Curated by a bearded revolutionary, we shucked some peas and shared some stories before a night of loud music and dancing.

Finca Mono Verde have ties with the Lalo Loor Dry Forest, a 500 acre reserve a 30 minute walk away from FMV. The forest sits in the transition zone between the wet forests to the north and the very dry forests of the south being a meeting place for a large number of animals from both ecosystems. In Ecuador less than 2% of the originally standing dry tropical forests exists. A dry tropical forest is characterised by the adaptations made to cope with the unusually long dry season weather that can see little to no rain for many months at a time.

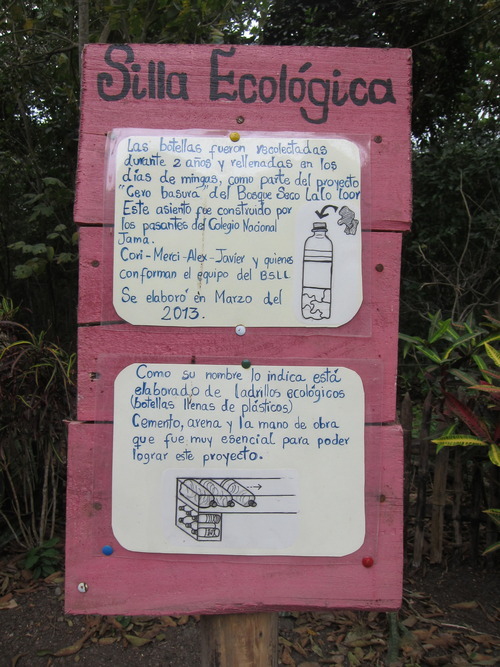

[a bench made from 'eco bricks', plastic bottles stuffed with plastic rubbish]

We went on a hike with Natalie with the knowledge in my mind that we were visiting a precious and fragile ecosystem that was possibly the last of its kind. Thankfully the Ceiba Foundation www.ceiba.org work to preserve, protect and educate people about the forest.

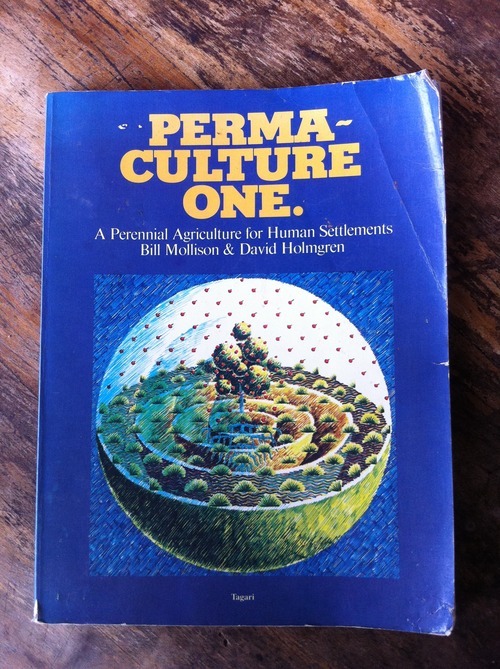

Alongside the many conversations we had, we also caught up on some reading, perhaps most notably, Sepp Holzer's Permaculture. A large gruff Austrian man who has transformed the Austrian mountainside where he resides, the self titled book is full of practical anecdotes and ideas, especially around mixed orchard and animals systems.

A really inspiring example of a young family working hard to grow and create, FMV was an incredibly welcoming place. It was encouraging to see how land, intelligently designed and well managed, could create a space for humans and wildlife alongside a caring cultivation. Heartening too. Despite the challanges, Monica and Arnaud, relatively young had directed and put all their energies into this idea called Finca Mono Verde which we had the could fortune to be a part of for a very short, yet felt, way.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Amazon Rainforest - Tiputini Biodiversity Station

Facts about this planetary ecosystem are as vast as the countries that it spans (those countries being Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana).

Millions of years old, more than half the world's species of plants and animals are found here. The Amazon makes up over half of the world's rainforests. With such sobriquets as “the world's lungs” and the “world's pharmacy” their global significance is no understatement.

But these are just words. These dense, pornographic forests are seething. And we had the pleasure to get up close and personal.

Not wanting to miss an opportunity to see these ecosystems that we felt had informed so much of tropical based permacultures, it was almost a homecoming of sorts to see this terrestrial biome.

Thank goodness we discovered the Tiputini Biodiversity Station (TBS), located in the pristine* eastern Ecuadorian Amazon tract of lowland rainforest, in the Yasuni Biosphere Reserve. Established in 1995 the research station takes its name after the Tiputini river, a tributary of the Napo River, which itself is a tributary of the mighty Amazon River – the second longest river in the world.

Our journey began in the jungle town of Coca (after a delightfully bumpy night bus from Quito). We met at a tacky riverside hotel and bar awaiting our ride. Details were vague and timings were off as we were told last minute that a film crew from one of the state TV channels would be joining us as Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa abandoned the radical Yasuni conservation plan despite Ecuadorians working to push a referendum on the question of whether oil companies could drill in one the most biodiverse places on earth.

Like the beginning of some drama, we meet our characters, who, pensively waiting, played at introductions in the oppressive afternoon heat. Lauren and Phil, permaculture know-it-alls, a young and green Scottish lad named Rory, an aspiring journalist Jason and a man and wife team Nancy and Jacob, one part worldly travellers, one part conspiracy crackpots (yes, they were from the U.S. of A). Boarding the boat with our incongruous pack lunch of cellophane’d sandwiches, packaged biscuits and saccharine juices, we were headed to one of the most abundant places on planet earth.

The wide Napo river drew in soon after we passed the gas flares from the oil extraction that is currently taking place in parts just outside of the Yasuni Biosphere reserve. After two hours on board we took a bus (another two hours) to the Tiputini river, picking up two avid scientists and TBS manager, Diego as our passports were checked by the Spanish owned petrochemical company operating nearby. There a motorised canoe swept us down the river for the last two hours as we saw the Amazon River Dolphin, and passed through tropical showers.

Arriving at the foot of a wooden staircase we ascended to a large open aired room which functioned as the cafeteria where Diego gave us the lowdown on the weekends activities. The research centre is made up of a two-storey lab, nine cabins, a library and classroom as well as electricity for the daytime. We soon settled in and were off on our first trip into the jungle. A serious field study facility with proper scientists meant we were in the company of people who cared and knew what they were talking about. We were delighted to meet one of their seasoned guides, Meyer. An absolute charm of a guide, his impish smile that would reveal a half broken front tooth took us on some memorable walks. Incredibly knowledgeable and patient with our questions, Meyer’s eyes would light like a schoolboy discovering something for the first time as he led us through the extraordinary world of the Amazon.

[Our wonderful guide Meyer]

We met the Sangre de Drago (Dragon’s Blood) tree, a wild crafted resin famous for its wound healing properties (he always carried a vial of the stuff); we cracked open some coconut like nuts and drank sweet water; he picked and played with mushrooms and insects; showed us the peripatetic palm Socratea exorrhiza, or, in common parlance the walking palm that takes its genus name ‘socratea’ after the itinerant rabble rousing philosopher Socrates. We had met the walking palm at Peter Kring’s wonderful La Isla botanical centre in Costa Rica; we were fed lemon ants, who, using their own "herbicide" (formic acid) create what myrmecologists (love that word, say it out loud and sound out why) call a devil’s garden: an immediately recognizable area where most of the plants have been killed by the ant’s acidic excretions except the one used as a home by the ants!; bird spotting with the monocular up a 30 plus metre observation tower.

[The healing dragons blood]

[The walking palm with its newly formed roots]

[Lemon ants eaten from their pod in the only tree they let grow in their acidic habitat]

[Nothing is wasted in nature, ants making quick work of a dead tarantula]

[Termites]

[A strangler fig tree doing it

s thing]

Despite the poor soils (acidic and typically red due to the oxidation of iron oxide in the topsoil which can often turn rivers and streams a copper colour after rain) the Amazon rainforest is incredibly rich biotically because of the volume of light and water that falls on it.

Meyer took us to the suspended walkways allowing us access to the upper canopy, where so much life occurs. Sighting birds and blown away by the views, one of the scariest things had to be ascending a rickety ladder up to a metre squared platform at the top of a tall tree reaching above the canopy layer. A sea of green the seemingly boundless rainforest was magnificent. Later on we heard from a distance the incoming rain that swept over us while we were still up in the trees. Our walk back was torrential but all the more memorable for the super soaking. What would a weekend in the Amazon be without a thorough drenching.

[The sketchiest ladder climb ever]

Our final excursion was a river tour. Invited to float with the current we got in the water and experienced heaving jungle on both sides as we were washed and whirled around as the boat sped off. Jokingly panicking about giant caimans, anacondas, deadly pirahanas and all the other things we could be prey too, floating down the Tiputini was a humbling perspective. After all, it's the water that defines much of the Amazon with season variations being in the metres and a matter of life or death for many animals.

The Teleamazonas crew wanted to get some nice cut away shots of us in the jungle. They also wanted to interview us! Jason, the NY based journalist who we shared many a good conservation with alerted us to these Youtube clips, emailing us about his story and writing, “Lauren you have a speaking role, Phil your impassioned pleas fell on dead ears apparently, but you are at least an extra.”

Check the videos out here. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0oae8BC1mx8 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JNSrmP44aFQ

My inchoate cry to the Ecuadorian people was either so radical that it had to be cut, or perhaps it was just plain garbled spanish. Alas, the world will never know. (I had suggested that the Ecuadorians ask some very hard questions as to where the money for all the oil drilling would go and to who).

That evening we were invited to Diego’s presentation on the use of their camera traps at the field centre. He underlined the value of camera traps in conservation work as they would often reveal a world of life and movement that would otherwise conduct itself furtively in the presence of humans. The star of the show no doubts being the noble Jaguar, Panthera onca. The world’s third largest feline the highly adaptive Jaguar once ranged from southern USA to northern Argentina. Prominent in ancient Mayan and Aztec mythology, the Jaguar retains its near mythical qualities as our modern culture draws upon its grace and strength for the inspiration of stuff to sell us. Declining numbers have given the Jaguar the unwelcome appellation of near threatened, “a species considered threatened with extinction in the near future.” The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) publish a Red List updating the conservation status of the world’s flora and fauna. Like a reverse dictionary, the world is lighting up species, that soon gone will diminish not just our vocabulary but understanding of the planet.

[A giant armadillo]

[Short eared dog]

[Red brocket deer]

[An ocelot]

[A pecari, wild pig]

[a puma]

[The true king of the jungle, the jaguar]

[fresh proof of their local existence]

TBS are currently looking for funds to continue their research into the jaguar population of Ecuador, a study that has never been done before which would create crucial information to protect them from further depletion. Get in touch with TBS to help out.

We left feeling buoyed by the fact that good people like Diego and Meyer are not only knowledgeable, but generous with their time. In a world where wilderness is disappearing and under threat from our own appetites we have to revisit our relationship to nature and reflect on our place in the ecology of things. As humans we have seen the stars, and plumbed the depths of the ocean. Aboard spaceship earth we can choose to pilot our way to a future that encompasses the life of all living things or charge our way along a path leaving a wake of destruction toward an unknown tomorrow.

That's all folks!

[The plum throated trogan]

For information about the TBS and the Amazon rainforest:

www.usfq.edu.ec/programas_academicos/Tiputini www.ran.org www.amazonwatch.org www.worldwilfe.org/places/amazon *natural, unspoiled or undeveloped** ** if you discount the TBS buildings

#Tiputini Biodiversity Station#Yasuni#universidad san francisco de quito#Jaguar#Ecuador#Amazon#Rainforest#Conservation

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Quilitoa Loop

Time to get our ramble on. South America was proving to be a very big place with plenty of walking to do. We had heard that the Quilatoa Loop, a trail that passes through Andean country of remote villages, black sheep and stunning scenery, was one of the best hikes to do.

First, we stopped off at the grubby and unappetising market town of Zumbahua. Products, people and livestock jostled side by side as huge trucks were toing and froing as fly by tourists made fleeting visits. A quick walk around and some deep fried chips later we managed to find a ride in the back of a pick up with sheep and locals returning home to the nearby village of Quilitoa, our first stop.

Lauren's long golden hair flapping in the wind, was an object of curiosity and delight to some of the women in the back with us with one smiling lady feeling it between her fingers. I, on the other hand, was trying to get the attention of the bemused sheep as we hurtled around the curving roads.

Quilitoa, also the name of the emerald green crater lake, sits at 3,900 metres above see level. The only attraction in town, the many hostels receive swathes of day trippers and ardent hikers. Half an hour down takes you to the foot of the the two mile wide lake, green-hued waters lapping your toes. The return, steep and at high altitude takes twice the time – or for a tidy fee in no time at all on the back of a donkey. Legend has it that the lake is connected to the sea.

The emerald green would change to steely blues and grey in the fading light as the sun fired the cloud covered mountain ranges in the west. High up and exposed the whipping winds and low temperatures kept us indoors as dinner was served to all the guests on a large table. Thankfully our small room had a wood fire stove that we kept going overnight.

The next day we walked around the rim of the lake affording us spectacular views, before descending toward Chugchilan. This was our first real hike in the Ecuadorian Andean countryside populated by small villages. The profile stood in sharp contrast to the neat plaid pattern of the rolling English landscape. Sharp, steep and vast the immediate terrain was of a sandy coloured brown, dotted with the alien, yet ubiquitous, eucalyptus tree busy sucking its surrounding soil dry while raising the acidity. It was dry season to be fair, but high up contrasts are more clear. Where there was water we saw clumps of greenery clutching for life to the flow of the life giving element. It was clear that the forests and trees of the area where stressed under the twin pressures of food and fuel. But is was incredible to see, when looking up close, the colours of the flowers that suited this high, dry climate.

Our arrival at the town of Guayama was occasioned by the appearance of all the townsfolk for some unknown civic event. Crossing the field, following the clear written instructions, we passed a football field with a bunch of kids playing a game. I wasn't sure, but some little chap had been following us at a distance from the town centre and ran across the football field anticipating our path. Watching us pass at a safe distance, whilst sucking on his two ice lollies, one in each hand, he shot his left arm in the air directing us to the correct path that took us to a winding trail into the canyon towards Rio Toachi. A short break for lunch at the bottom and a steep walk later we arrived at Chugchilan.

We stayed at Hostel Cloud Forest where we met a Robert de Niro look-a-like who was supposedly the head chef. With more walks to do we had a couple of nights to explore the area.

The labelled ridge walk began badly but ended well. We soon got lost and arrived at the house of a family. By chance, it was the home of one of the hostel workers who we thankfully recognised. We all had a laugh and were led by her grandfather who was heading out to move his cows. Setting us on the right path we got on the ridgeline where we had stunning views on both sides. We visited a local cheese factory that was underwhelming and overpriced and failed to find a nearby waterfall. Undeterred we carried on and made our way to town after a long day of walking.

The easiest hike was the short walk out of town to the Canyon Plateau where cultivated land abruptly ended over a sheer drop cleaving the land to form a verdant canyon.

One of the highlights was our visit to The Black Sheep Inn – a posh eco-lodge that was just outside of town and way out of our budget. Thankfully they allowed us to have a snoop around for some inspiration.

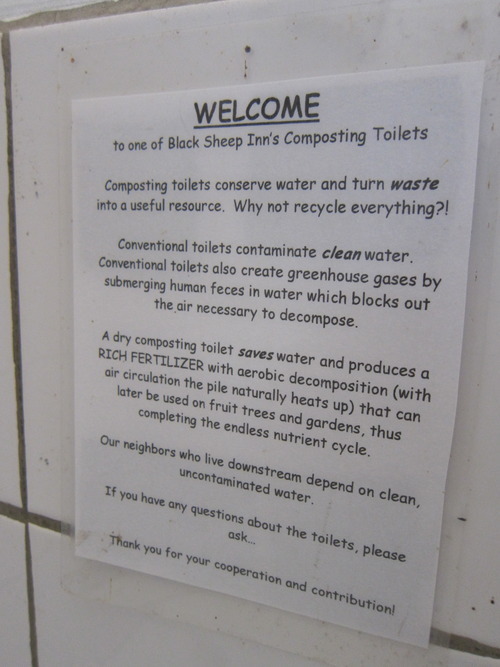

Charmed by the beautiful rooms, bottled walls, and wood burning stoves was particularly taken by the beautiful compost loos. Designed with small indoor flower gardens fed with water from the roof and the wash basins, each toilet proudly displayed a copy of 'The Toilet Papers' by Sim Van der Ryn, a new book to me. The Black Sheep Inn website dedicated a lot of space to their compost toilets, proclaiming proudly how it is often the subject of dinner time conversation and people's photos. A brief entry from the beginning of the book offers readers a thoughtful reflection on the concept of 'waste':

“The idea of waste, of something unusable, reveals an incomplete understanding of how things work. Nature admits no waste. Nothing is left over, everything is joined in the spiral of life. Perhaps other cultures know this better than we, for they have no concept of, no word for, waste.”

This idea appears to form the backbone of the Black Sheep Inn's philosophy as we met one of the founders Andres, whilst out feeding kitchen scraps to the pigs. He then showed us to their cuy (guinea pigs) that live in a six foot deep pit allowing them to express their natural habit of borrowing holes. Alongside their animals, appropriate tech and food systems a big part of the Black Sheep Inn's work is in the field of local education and conservation, most notably their efforts in preserving the nearby Iliniza Ecological Reserve that we sadly didn't get to see. A working, functional and beautiful site we were encouraged by their good work.

Check them out: www.blacksheepinn.com twitter @blacksheepinn www.facebook.com/BlackSheepInn

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I hope you had a great time in Bogota, but people from the city are called "bogotanos" or "rolos".

thanks for this!

0 notes

Text

The Tinku Centre

Built on an abandoned basketball court, The Tinku Centre in a leafy suburb of Quito is a permaculture paradise afloat in a sea of city.

We had learnt of the place from our friends, Ryan and Leticia of comuntierra.org We were really excited to see how permaculture would look in an urban setting in what textbooks and teachers say is a third-world country. Markos, founder and manager of the site, kindly invited us to visit on a stunningly sunny day.

We walked into a permaculture design course with a small group of people made up of a travelling Argentine cobbler, a few Quitenos, and a local engineering student amongst others. Markos was in class mode as he enthused about how permaculture could look in an increasingly crowded world.

Everyone was incredibly welcoming as we shared a snack of biscuits, tea, and nibbles before moving outside with the class to talk about best practice when it comes to mixing mud for adobe bricks. It was clear from the outset that Markos's eagerness was shared with the students as we literally got our feet and hands dirty.

We were also very grateful to Markos for taking some time out to do a little tour with us. We were struck by how busy, yet organised, such a tight little space could be. A fair portion of the grounds are devoted to growing, but at its core Tinku is a space for people to come and learn, play and do – valuable tools in our technological society where work is increasingly something that is done to you, rather than something you choose to do. A nice touch was seeing the rows of seed balls, having recently read Fukuoka's 'Sowing Seeds in the Desert.'

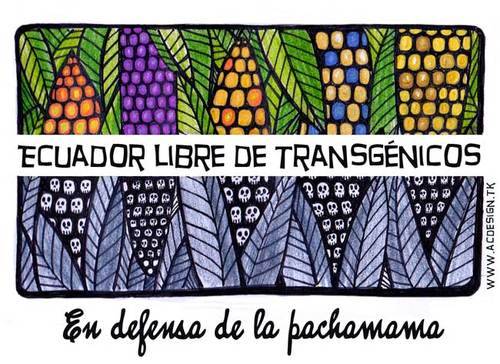

Markos also showed us a beautiful seed bank in the making – seed saving a large part of Tinku's mission and culturally prominent past time in Ecuador that is proud of its heritage corn and GM free maize (corn).

We left feeling inspired, touched by the fact that there are people who care and work to make change in a positive and sharing way. One thought that did strike me, having just returned from the Galapagos, was the idea of islands as places where things happen in their own time and their own way. Seeing how such seditious thoughts as saving seeds and promulgating food sovereignty was happening in a city, made us appreciate the rarity and import of such a place. On the way to the Tinku we passed a road by the name of La Isla, and seeing the centre, tucked between a car park a scratch of lawn mown green, the idea of a sanctuary, a green haven really struck home.

So far we had travelled overland from Mexico to Ecuador, with most of the huge South American continent still in front of us. We had seen so much beauty and so much ugliness. How, in a global culture of commerce and capital, was the natural world to stand a chance I would often think. What, as humans, is our role on a planet being cannibalised? How are we to set ourselves against the tide of inevitable species loss, destruction and the narrowing of food chains? How, if at all, could permaculture help answer these questions?

Appreciating the earth as a system is founded in the knowledge that the spheres of the solid earth, the biosphere, the atmosphere, and the atmosphere is one of interaction.

Along the road we would comment to our hosts and friends that we had met along the way, how the realities that they had carved out were pockets of sanity. But like the many islands we've encountered interaction is key. It's not just a question of turning inwards, of turning away, as some choose to do, but of this island earth, and such models and spaces as the Tinku Centre are sanctuaries, of being a place people come to and along the way create their own archipelago of hope.

As a lover of words, particularly the sound 'Tinku' makes when spoken I was intrigued as to what the word means. According to Wikipedia, Tinku, a Bolivian Aymara tradition is a ritualistic combat. In Quechua, the tongue of many modern day Ecuadorians, it means 'encounter'; in Aymara, a different peoples and language, who also live in what is known as Ecuador, it means 'physical attack.' I like this dual meaning as from a permaculture perspective one has to train oneself for a form of “attack”, or ridicule for ideas that may seem outré or simply non-tenable in a conventional society. As Bill Mollison quipped, permaculture is a form of environmental ju-jitsu.

For more info about the Tinku Centre:

http://runakawsai.org www.facebook.com/runakawsai/info twitter.com/runakawsai

0 notes

Text

Galapagos

My brother was going to disown me. We had to go. Galapagos wasn't just a place, it was a concept, an idea, firmly rooted in the mind of man as Darwin's living laboratory. It was a place that had been BBC'd by David Attenborough, where extraordinary images of a strange world had been broadcast into our minds. We had to go.

Out of our league - and budget - we sweated over a carefully worded email to our families asking for a loan to get to pay for the flight and an all expenses cruise. Their response was a quick and unanimous yes. Phew! What, after all, is money other than a lien against the planet... as well as an IOU against your parents.

We were very excited and so set to do our homework. After hours of traipsing around the city we returned to the first place we had found, CarpeDM Adventures. Led to the Galaven, an 88 foot expedition vessel for 20, by ex-pat Brighton British chap, Dorian we were booked!

Our first flight for a long time, we were a little awed by the shiny airport and the shiny people with their shiny equipment and wrist watches. This is where the Ecuadorian rich hangs out.

Our eight day, seven night itinerary went as follows. For a more economical version just see the pics.

Tuesday, our first day, was arrival at San Cristobal island, settling in, and then an afternoon at the 'Jacinto Gordillo' turtle breeding centre. We walked a little around the port, the funk of sea lion apparent as they lolled on benches, slept across paths, and lounged on the beach. As well as their distinctive smell you'd often hear them sighing and snorting. Fat and lazy, the sea lions had done well in wet season when the sea provided plenty of fish in the sea.

[a galapagos mockingbird]