Text

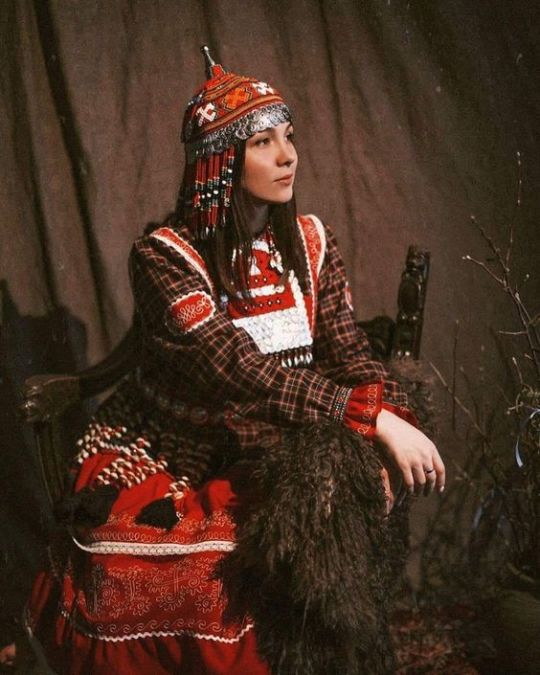

Traditional clothing from Ruse, Bulgaria

source

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Our mothers are always dressed in black

Ivan Milev, Bulgaria, 1926.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

Esquire Photoshoot with Lee Soo Hyuk

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Girls, braided in "плителчета" style"/ Hairstyles of Banat Bulgarian girls from Bardarski Geran

Source

378 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“KENSSHI” POSTER // масло черного тмина

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maslo Chernogo Tmina – “Kensshi” (dir. Aisultan Seitov)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

„Odchádza clovek“ / "Отива си човек" / "The man leaves" is a documentary on Bulgarian funeral rites by Martin Slivka, a Slovak documentary filmmaker, director, screenwriter, and ethnographer.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women's hair in Bulgarian folk beliefs

(Translation of this article, written by Anelia Krumova)

Since young age, girls were taught from their mothers and grandmothers to put special care to their hair. This learning began with the most important rule - "Hair must not be cut from the ends, for that's of ones soul and head!". If needed, the ends of the hair would have been carefully removed with the help of a stone. Hair that would fall out during combing, would be gathered and be used for the makings of braids, which were additionally adjusted. The woman would never part with them and the braids would even be buried with her. In rare cases, the hair was buried under trendafil, walled up in a hole in the wall or burned.

People believed that "one must look at woman's waist and hair". Women with lush hair were thought as strong and hardworking, capable of bearing childen. This is why, when young men would choose a bride, they'd check out the hair. In response, young women would show off the thickness, volume and length of their hair, as well as accessories to it, demonstrating sexual power.

Having your hair uncovered was a privilege of the young unwed women, so they could be seen. Married women were forbidden to do so. Headcovering was defined as the main sign of the woman's marital status - the headscarf showed that the bride was subdued. Dimitar Marinov, for example, reveals the obligation of a married woman to hide her hair from the world and to reveal it only to her husband. The same statement was made by Lubomir Miletic in his study of the population of Northeastern Bulgaria. He even went on to clarify, that removing the headscarf from a married woman and showing open hair is, according to customary law, tantamount to dissolving the marriage. The bride's hair was hidden or trimmed, and decorations were formed over her forehead, so that the hair of the already married woman could not be seen.

However, it is interesting what made a society, which admired hair so much, go to another strict extreme and impose its concealment. The only explanation could be related to the fact that according to popular belief, in the beginning people were all hairy, and when they began to be baptized, they were left with hair only on the head, armpits and abdomen. Thus, the hair remains outside the boundaries of the sacred sign, it becomes a sin. The sexual power of the woman, expressed in the lush and voluminous hair, became the property and possession only of the husband. Even the hair that fell out during the wedding braid was sent to the girl's new home, back with the chaise, wrapped around a dogwood stick with red woolen thread.

The most severe ban on hair is related to its unraveling in public - girls would braid it secretly all night. This was done to hide the unbraided hair from others. It was believed that it belonged to another world - of the night, of death. In folk beliefs, this was the essence of the somodivas, the plagues and other supernatural beings. The demonic female beings, that belonged to the so-called "restless souls" who remained on the border between the two worlds, had their hair loose. Uncombed, tousled hair, the people referred to as "plague - like".

A woman can have her hair untangled only in certain ritual situations: during lazaruvane and when she has given birth. The closest relative of the deceased could have their hair loose - in most cases it was the daughter. Unbraided hair was considered a sign of transition.

Another ban was that a man was not allowed to see a woman washing her hair.

The braiding done at a funeral, when entering that world, asymmetrical to the earthly, social, was different. Unlike the living woman, the dead woman had her hair braided the other way around,from the inside out. Women that were loved by zmeys had their hair the same way. The dragon's lover intertwined in the same way. In folk songs, this braiding was known as "zmeychevo".

In the past, hair not only marked spaces - social or beyond, but overturned them if the rules are not followed. Hence the belief in the strong magical vulnerability of hair. She gains resilience only through strict adherence to certain rules of hairstyle and veil.

182 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paintings by Czech artist Jan (Ivan) Mrkvička created during his time in Bulgaria

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aguševi Konaci (Aga's Konaks), enclosed living room on upper level

Mogilica (Mogilitsa), Bulgaria

This large corner room on the upper floor of the northern konak is called a kiosk (кьошк, k'ošk), richly appointed in woodwork and textiles, a space for special gatherings. With windows on three sides, this space overlooks the second and third courtyards and the slate roofs of buildings below. The carved wooden ceiling is especially ornate, a testament to the builders' talents. (photo 2000)

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rusi Čorbadži house, interior of čardak

Žeravna, Bulgaria

The čardak (meeting and working place), has an elevated sofa (sitting area) that is well lit and ventilated. The traditional wooden grills have exterior shutters to protect the space from inclement weather. The furnishings show the traditional use of such a space with a low table set at the proper height for those sitting on the floor. The columns and paneling have been shaped and edged and the high shelving provides storage for plates and other objects used in the space. (photo 2000)

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daskalova kăšta, view within čardak

Tryavna, Bulgaria

The čardak overlooks the entrance garden and formerly incorporated a projecting sitting platform (kiosk). The wood columns have carved bases at the top of the railing to form cylindrical shafts and carved capitals that support the curved bolsters and beams above. The stair at one end leads to the ground level, while handsome living rooms, with carved woodwork, open to the right. (photo 2000)

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Best Picture 2020

Winner:

Nomadland (Chloé Zhao)

Runners Up:

Beanpole (Kantemir Balagov) I’m Thinking of Ending Things (Charlie Kaufman) Possessor (Brandon Cronenberg) The Father (Florian Zeller) The Invisible Man (Leigh Whannell) The Hater (Jan Komasa) The Nest (Sean Durkin) She Dies Tomorrow (Amy Seimetz) Matthias & Maxime (Xavier Dolan)

36 notes

·

View notes