Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Sensing

Jan 1, 2017 – Of Vietnam, from Nom Khiaw, Laos

And now I exhale. Before a 1,000 foot looming karst that plays hide and seek in the mist of the Laos cloud forest, I embrace the rainy day while I sit on the thatch-roofed porch of my well-appointed bungalow at the interstices. These spaces in between, neither of this world nor outside it, not attached to past or future, breed reflection like no other.

Preceded by a particularly immersive weekend meditation retreat, this travel experience, more than most, has allowed me to almost watch the ebb and flow of my reactions as a detached observer. I always find that displacing oneself from the familiarity of home conjures feelings of every extreme. The elation of a strong, steaming shower, after days without, can be replaced with shocking swiftness by the devastation of a boat trip to a coveted landscape cancelled due to unseasonable rain. Just as mercurial was the titillation I felt, on Christmas Eve in Vietnam, when my hotel staff performed a hilarious choreographed version of Uptown Funk in Santa suits – too soon followed by a sleepless night because India’s bureaucratic and labyrinthian e-visa website threatened to thwart my ability to gain entry in the country where I am committed to deliver a youth arts project in just 2 weeks.

However, I am no longer surprised when such unabashed joy erodes the moment another travel aspiration is dashed. I’ve ventured far from creature comforts often enough to realize that my daily happiness on the road is inextricably linked to the management of my expectations. And so I secretly hoard my hopes, like one does their vices (whisky under the bed or sweets in a hard to reach cookie jar). And instead I strive to absorb each travel experience like a sponge – neutral and receptive, as open to saturation as I am ready to be wrung out to dry.

Hanoi boasts more cafes than Vancouver, Seattle, and Portland combined. And one of our favorites was the Notes Café. Visitors are invited to leave messages on pastel sticky notes that wallpaper this three-story, 10-by-10 sliver, in the centre of town. On mine I wrote, “live every day like a traveler” by which I mean to savor every sensation like it’s the first time you’ve ever encountered it.

A lofty goal, but one far more easily achieved when a routine day includes the blood-curdling squeals of a giant pig as Hmong tribesman try to tie it, alive, to the back of their moped; the ubiquitous smell of fish sauce, cigarettes and singed flesh; the glories of a woman’s firm hand kneading all of your worries from between your toes; the taste of a liquid hot coconut pancake bought on the street for a quarter; or the hourly site of a mother tenderly picking lice from her child’s hair on the sidewalk, their family’s “dirty laundry” laid bare, the way it seems everyone lives their lives in this part of the world – in public, proud and shameless. Perhaps it’s why all their café chairs face outwards, where an endless array of stimuli abounds. Weddings are held in open downtown patios; men can get a shave or a haircut on every street corner; electrical wires hang in exposed, tangled webs draped from block to block; and cyclists ride past, dwarfed by enough wares to fill a whole floor of a department store. I envy such candor. We could all learn from their honesty. And I think such transparency lends itself to much deeper compassion.

Sense-making

Jan 1, 2017 – Of Vietnam, from Nom Khiaw, Laos

Another favorite aspect of travel, for me, is sense-making. It was three days before we learned that the balloons cryptically sold at every Hanoi bar were filled with shisha (a flavored smoke enjoyed in Hookah clubs around the world). The same amount of time was required to realize that the amplified chant which woke us every dawn was communist propaganda emanating from the loud-speakers of their garbage trucks. Conversely, the donut ladies and shoe repair boys were a much quicker read. Not two minutes off our airport bus, we were accosted, unawares, by a woman in a triangular straw hat who popped free TimBits in our mouths. This seemed like a friendly welcome, but it turns out the same ruse happens every 15 minutes in Hanoi. So, we learned to keep our mouths closed when we passed them to avoid the pressure to buy more. Just a minute later, with our sore-thumb status confirmed by our rolled suitcases, a sharp-eyed, young male bent at my feet and proceeded to glue the sole of my shoe, near the toe, where it had begun to detach. While I reached for a 5,000 dong note (30 cents) to thank him, he had already grabbed his needle and mismatched thread, ripped my sneaker off my foot, and continued to repair the undamaged heel. Then, he asked for the equivalent of a whopping $10 for his unsolicited 2 minutes of labor and mismatched gold scar which he left on the treasured shoes that I’d bought on my last adventure, in Colombia. We settled on a buck, and I chocked it up to a great tale. Now, I’m just hoping that I’ll get them polished in Kenya then stolen in Paris so I’ll eventually collect a story from every continent.

There are sensations I count on as sort of traveler’s homing-devices in every part of the world. Rooster wake-up calls, unidentified prickly fruits, chromatic bird calls, steaming street food, traffic chaos, and smoky sunsets. Then, there are those unique to certain regions. And I have to confess that Asia’s tickle me most. The constant waft of Buddhist incense. The colorful light that paper lanterns lend to almost every setting. The gorgeous silks and embroidered textiles that line the markets like flags attesting to the efforts of the women who have toiled over these precious pieces. And then, of course, the delectable food that no amount of Delhi belly can deter me from trying. There is noodle soup, sticky rice, hot pots, curry, sweet iced coffees, teas, and fried bananas to name a mere few. My mouth is watering as I write. So much so, I think it’s time to break for dinner….

Travel Lessons

Jan 5, 2017 – Of Vietnam, from Luang Prabang, Laos

Certain insight can be revealed about a culture through one’s own eyes. The art nouveau propaganda posters that abound in Vietnam act as souvenirs that loudly scream of their unabashed hatred for the US during the “American War”, as they aptly call it. Conversely, a crowd of children yelling in a public park turned out to be a game of Tug of War – an ironic demonstration of their more peaceful present times. Thoughtfully restored French colonial structures and fresh baked baguettes at every café infer a certain reconciliation with their former imperialists. As did our experience on Christmas Eve, when we accidentally happened upon thousands of locals singing Silent Night in front of a jumbotron outside St Joseph’s Cathedral, where several hundreds more attended the service. Though a vestige of their colonizer’s religion, the profound sincerity of their adopted faith gave us chills.

Other truths have to be gleaned from more deliberate research. Hanoi’s impressive Women’s Museum (an institution I wish existed in every nation) taught me that females have been leaders in Vietnam for centuries (politically, militarily, scholarly and otherwise). Perhaps influenced by the history of numerous matrilineal tribes, women seem largely respected and included in Vietnamese public life – not only relegated to domestic responsibilities as we’ve observed more in places like India and Morocco. Of course, along with this has come grueling physical and low-paid labor, in sweat shops, on farms, and everywhere on the streets where you see them carry burdensome wicker baskets dripping with vegetables or chickens or toys, balanced by a mere bamboo pole that rests on their probably thickly calloused shoulders.

But I always learn the most interesting things from my direct interactions with locals. Hanoi is not without its hipsters. Microbrew culture is budding. Latte art and mojitos are easy to find. And the trendy Tadioto Bar was certainly the best example. This dimly lit, art-gallery-slash-20-seater drinking hole hosts Vietnam’s artsy literati types, along with the few foreigners who can find it. The 27-year old manager, who did not look a day over 16, returned to his hometown to swap philosophical banter with his clientele after a grad school stint in Wisconsin as a poetry major. And we were privileged to a long chat with him once the place had emptied. He spoke about a small but thriving educated class, eager to study abroad. He criticized the hypocrisy of the blatant consumerist values he perceives in Vietnam while it remains a Communist state. His female companion, (an actual 16-year old far too big for her britches, sipping tea amidst her adult peers while home on holiday from her New Jersey prep school), added that many of her compatriots were quick to capitalize on the ease with which a clever person could make good money in her country. And when we asked about the danger of dissent (like we’d previously observed in Cuba, for example), they shared that because many “revolutionary” thinkers can relatively maintain the comfortable lifestyle they want, within the current regime, their objections remain more ideological than action-based because their need to make waves is not great enough. Of course, such a conversation is merely a glimpse of their political reality, and received only through the lens of a few select opinions. However, it still added much richer hues to the picture of Vietnam that I had before my visit.

Tours and Chores

January 6, 2017 – Of Vietnam, from Luang Prabang

While I travel primarily to gain cultural insight, not all of my travel choices have such lofty intentions. I am also hungry for new experiences and certainly allow myself to indulge in occasional not-to-miss attractions along the way. In Vietnam, one of those was HaLong Bay, where thousands of mythically shaped karst mountains hold court in the South China Sea, like creatures out of a horror film. One can’t avoid sharing this World Wonder with 2,000 other travelers who dot the coast in orange-sailed junket boats on any given day. And whether you want to or not, you are shuttled through an action-packed itinerary that includes a cave trek, kayaking, and a cooking class. Not a bad combo at all, but the constant demands on our minute-by-minute behavior had me wondering if they’d dictate when I could pee or even breathe too. Such guided programs do, however, offer some surprises. And while I dreaded the visit to a cultured pearl farm, for fear of aggressive sales pressure, I was astounded by the lengths to which our species manipulates nature to mine it for the tiniest gems. After a test tube baby-like breeding process that mixes a dead oyster’s shell lining with organic flesh, they inject this into a living mollusk in the hopes that a drop will fuse with sand and other solid ocean matter to produce the coveted pearl. Of course, it only works 3 out of 10 times, and then only 10% of those pearls are “perfect” sellable specimens. So, with a 3 % overall success rate, it’s no wonder this laborious process reaps such expensive jewelry. I was left wondering who ever thought up such craziness and why, but that’s a disorienting state in which I often find myself as I travel, and I invite it.

At the end of our two-day tour, we were mildly disappointed with the overcast weather that never lifted. But, for the most part, this only meant one less screen saver shot than we’d hoped. And, of course, that is never a real reason to travel. Meanwhile, the shrouded look did lend its own magic, and I still feel very grateful to have seen this one-of-a-kind landscapes.

Insights

January 9, 2017 – Of Laos, from Siem Reap, Cambodia

There are few places that can surprise anymore. Facebook, Instagram, the Amazing Race, our intrepid friends’ travel slideshow parties, and much cheaper, easier flights than ever before mean that at least someone somewhere has told you/showed you about nearly every place on earth. And though Laos is far less traveled to than most spots, surely some of our adventurous buddies had already ventured there. However, we’d resisted looking at their photos, or others, as much as possible prior to our trip. So, the country’s fifty shades of green, which barely resemble the same number that paint BC’s Sea to Sky corridor, were wonderous to discover.

The design sensibilities of the tribal weavers, the Buddhist temple-builders, and the interior decorators of Luang Prabang’s stylish cafes constantly exceeded our expectations. And the unwavering calm, clear-eyed joy of the Laotian people continued to amaze us while we failed to witness an exceptional case by our tenth day there.

But most shocking was the 100-year-old film, Chang, that documented daily Hmong life, deep in the Northern jungle, in a way that has not been rivalled before or since. It follows a loving family of four, in a scant stilted home, who lived at times in harmony and at others in discord with a host of creatures that surrounded them. Chickens, pigs, goats, giant lizards, pet baby bears, and howler monkeys they counted as friends or food. But leopards, tigers, cobras and a full herd of 400 elephants threatened them daily. It’s difficult to say what astounded us more - the boldness of this courageous filmmaker, or the preposterousness of this family’s efforts to outwit their far fiercer foes. Even more strange is the fact that the film is virtually unknown, and went entirely missing for almost 65 years until its recent rediscovery. So, while part of me wishes to keep Laos’s secrets amongst the few who are willing to go there and see for themselves, it would certainly benefit the study of Mekong’s indigenous people, and perhaps the anthropological understanding of other aboriginal cultures if this deserved film were to receive global circulation. However, for now, it is only available in the most quaint and romantic bike/walk-in theatre ever, each night at 7:30, in the garden of one of Luang Prabang’s most chic hotels – popcorn, beer and all.

We were granted another privileged and intimate peek into Laos culture when we took a slow boat up the Nam Ou river with our guide Wong, whose story spoke volumes about his people. Wong was born in a remote Northern farming village, the middle child of 11 siblings – the boys outnumbering the girls by only 1. Raised by parents with a strong value for education, Wong woke at 3 am, from the age of 5, to have enough time to steam rice for his “lunchbox” and then walk a whopping 3 hours to the nearest primary school, only to study from 7-1 and then repeat the whole journey home, every afternoon, before dark. Wishing to improve his access to learning, Wong chose, of his own volition, to become a monk at the age of 11, which meant that he had to move to Vientiene, 600 kilometres from home, to study at a temple school there. He generously shared that he cried non-stop for his first 3-days, but his homesickness abated when he soon began to make close friends. It was 7 years before he even once returned to his village, but his parents did make the long bus trek, once per year, to see him.

At 18, again by choice, Wong incurred a self-imposed fast, during which he remained in his room for 8-days of contemplative meditation, to determine if the monastic life was truly for him. He emerged spiritually strengthened but physically weakened, and his retreat was followed by a 6 days in the hospital. But his resolve to seek further university study and to one day marry caused him to disavow celibacy and asceticism. Most Laotians follow Therevadan Buddhism which allows for men and women to enter and exit monastic life (unlike the Dalai Lama’s Mahayana branch which requires a lifetime commitment), so Wong was not alone in his life transition. More than half of his childhood mates also left the monkhood and he sadly lost touch with all of them. His desire for love has not yet panned out either. He confessed to his discovery of Lao whisky and beer when he nursed a broken heart after his first love ended because he could not abide a possessive or jealous girlfriend. But his career aspirations did successfully lead him to complete degrees in English and Law. He also acknowledged that he knew he could be much more effective as a lay person, providing legal counsel to people in villages like his own, because many hill tribe people are not Buddhist and are thus less receptive to Buddhist monks.

So now, he has reached the arduous internship phase that his country requires of all bureaucrats. And this means that he must work full-time, without pay, potentially for several years, until he passes a very demanding exam to qualify as a legal officer. Meanwhile, he has to work weekends to pay for his living expenses, which is why we found ourselves scrambling into a limestone cave, swimming in jungle waterfalls, passing gargantuan 10-inch amphibious millipedes en route to a jungle waterfall, and kayaking cavernous river valleys with our charming guide who taught us so much.

View from Two Wheels

January 10, 2017 – Of Laos, from Siem Reap, Cambodia

Life is always observed most vibrantly for me from a bicycle. This slower two-wheeled pace, though faster than walking, still allows for careful observation of the people, places and things you pass along the road. And rather than to simply watch it, you are truly in it, moving as so many others do in the world, by human-powered pedal. Our Laos trip covered 300 k in 4 days, a manageable distance that still enabled us to cover some real ground.

Slipping towards and away from the Mekong and then Nam Ou waters, we were hugged by stunning views at every turn. But a few sights stand out in particular, for better or worse. -Triangular-hatted women working impossibly green rice fields, just like you might mythically imagine in any rural Southeast Asian scene. -Formerly-adorable, brown and black decapitated goat heads, on sale at the side of the road for god knows what culinary purpose. -Straw roofs covered in drying river weed to prepare one of our favorite Laotian treats, kaiphen, a scrumptious nori-style roasted greens served with sticky rice.

-Another seemingly unnecessary gas station, no less than every 10 k (5 times more prevalent than guest houses, for sure). We figured this gave the residents of the tiny villages en route a way to fill up their motor bikes without having to travel too far, but the infrastructure for these fossil fuel beasts seemed incongruous amidst the primitive nature of the surrounding communities. -And Hmong tribal children honoring their New Year celebration (Pei Mei) in incredibly festive traditional dress.

But the worst blight to our senses were the series of imposing dams which the Laos government has hired China Energy to build all over the country. I don’t think that there is any edifice that serves as a greater physical manifestation of humanity’s raping of Mother Earth than a giant concrete dam. And the thoughtless red spray-painted numbers scrawled across hundreds of families’ homes, slotted for demolition, were a stark reminder of the displacement such projects incur. Even more tragic is the fact that Laos is overdeveloping its hydro power for its population’s needs. So, it plans to sell it to its neighbors. Little beautiful has been built in the name of greed and these Mekong scars are no exception.

Massage Dynamics

January 10, 2017 – Of Laos, from Siem Reap, Cambodia It seems unfair that the aches and pains gained from a one-week bike tour could be so instantly and cheaply alleviated at your destination. But Luang Prabang is, indeed, the perfect landing spot for saddle sores, throbbing quads, and nagging shoulder injuries. The full menu of body treatments is available there (foot, Thai, Swedish, hot stone, or head massages). And we availed ourselves of all of them. When I pay a pretty penny for this luxury at home, I think I take for granted the true preciousness of the exchange. But somehow, when such bliss is doled out for less than $10 an hour, I am struck by the intimacy and privilege of having a complete stranger come into such close and loving contact with your flesh. Usually these are wordless encounters delivered by nameless people, which should not seem so touching (pardon the pun). However, the Laotian touch moved me. And because some of my former foreign masseuses have so mindlessly dialed it in (checking Facebook as they annoyingly rub the same 4 inches of my calf for ten minutes), I know the difference when I feel it. Such a blessing.

Post-massage bliss:

Expat Reflections

January 11, 2017 – Of expats I met along the way, from Kuala Lumpur

So, I’ve taken to waiting to record my travel thoughts until I reach each subsequent country – letting the tastes of Vietnam marry before writing about them in Laos; weaving the lessons from Laos into a story once I’ve arrived in Malaysia. And so it is here, in an Aussie style coffee shop in Kuala Lumpur, complete with its chalkboard menu scrawled in trendy font and wistful songstress tunes, that I sip a flat white and continue my reflections from Luang Prabang. And oh, how I love to let these foreign place names tickle my tongue. My next destination is my favorite – Kaliyampoondi, the Indian village where we will lead our youth arts project. And if the piece we create with the kids there is anywhere near as musical as its name we’ll be in great shape!

Throughout the journey we’ve met a host of ex-pats, (living and working in these countries). And I’ve become increasingly interested in understanding the dynamics of their lives abroad. So, since it is during this phase that I am the guest of my KL-based friend, Lisa Sauer, (the most intrepid traveller I know , with only 3 countries left on the globe unvisited) and her husband Jeff, I have been able to gain a keener insight into this topic. As someone who has had at least temporary residence in 7 countries, I am sensitive to the rewards, challenges and ethical quandaries that foreign living can pose. And each of the characters we’ve met on this trip have handled these in quite disparate ways.

Harps was a brawny Aussie who served as the virtual impresario of Nong Khiaw – a hostel owner and an expert on everything from the best river guide, to the coolest locals’ New Years Eve party, to the cheapest beer in town. He was already three sheets to the wind when we met him, at around 6 pm on December 31st, which added several hues to his usual colorful delivery. And he tipped us off to the riverside ritual, where locals floated banana leaf boats decorated with flowers, candles and incense to send their new year’s intentions down the Nam Ou.

We gratefully joined in, then later saw him at the town’s midnight bash, participating in a traditional Laotian dance (that oddly resembled American square dancing) while the mayor and his wife provided “musical” accompaniment with completely tone-deaf karaoke (seemingly the only kind in Laos, as I documented on the attached sound file recorded in Luang Prabang two days later). Harps seemed fairly well integrated into the culture, but was also quick to criticize several locally-run outfitters who he warned were out to fleece tourists. Interestingly, we met one such local competitor the following day, and this charming 32-year old bar/hostel/travel agent owner had similarly controversial things to say about foreign business owners (though, respectfully, without naming names). So, these two simple exchanges revealed volumes about the tensions that arise with ex-pat ownership.

I was made aware of another ex-pat conundrum in Siem Reap, Cambodia when I checked out a yoga studio in the town’s tourist hub. Paul was the South African owner of Ahimsa Yoga. And while the Sanskrit word ahimsa translates as non-harm, his demeanor was anything but harmless. When I inquired about the class style, schedule, etc. I was barraged with an uninvited litany of complaints about the LA hard-body divas who come to his classes thinking they have nothing to learn, the phony instructors who have commercialized yoga world-wide, and the foolishness of the scantically-clad co-eds that prance through his studio as well as the Siem Reap streets and then complain when local Buddhist men (not accustomed to seeing a women’s knee or shoulder in public) harass them. I took that as my cue not to return for the sunset flow class and chalked it up to another angry escapee, seeking refuge from the discontent of home only to swap it for frustrations of another ilk.

We did, however, meet several far more exemplary models of ex-pats doing genuine good abroad. The Aussie manager of Luang Prabang’s Saffron Café, another perfectly first-world styled coffee shop, partners with a local owner. They use only Laotian beans, roasters and staff and contribute 100% of business profits to Laos communities of need. And Joanna was the British owner of Ok Pok Tok, a divine respite perched over the Mekong, where we stayed for two nights. The four romantic villas are surrounded by lush gardens and adorned with top-quality textiles crafted by the tribal women they employ from around the country at the weavers coop which is located on the same grounds. Sandra and her Laotian business partner travel widely to discover and support indigenous artisans. From some they purchase wares in their remote communities and take on all the risk to sell them to tourists in the city. And for another 30 villagers, they offer a home and a job on their beautiful premises.

Inspirations

January 11, 2017 – Of Southeast Asian NGO’s, from Kuala Lumpur

Foreigners were hardly the only philanthropic folks we met either. Local social enterprises abound in Laos and Cambodia. Friends International is an awesome organization that provides drop-in centres, transition homes, and education to marginalized youth. It also trains street kids from both countries in gourmet cooking and then employs them in one of their 8 restaurants (in LP, Siem Reap, Phnom Penh and more). We ate at Luang Prabang’s branch, Kaiphen (named after the aforementioned riverweed snack). And it was hands-down our best meal in South East Asia. Laotian-style fish tacos with mango salsa, smoked eggplant puree on homemade baguettes, as well as prawn corn fritters offered us a delectable twist on local cuisine. And I scored a funky wallet, repurposed from Cambodian magazines, at their gift shop too.

Another notable project, and one quite relevant to my work, is Phare, the Cambodian circus troupe we saw perform in Siem Reap. Their pole climbing, silks flying, fire juggling acrobatics were astounding. But even more impressive was the Art for Social Change aspect that similarly trained street youth in circus arts intent on creating professional opportunities for them. The act included high-quality live music, dance, acting and storytelling as well, because their school provides a fully interdisciplinary training. And the end product, whose narrative had a powerful social message about bullying, could easily rival Cirque de Soleil standards too.

But the most fascinating NGO I discovered is run by Fi, who sat next to me on my flight from Siem Reap to Kuala Lumpur. His company’s innovative app, AgriBuddy, is serving thousands of rural farmers to digitally track their GPS location, size, crop inventory, fertilizer needs, etc., so that they can legitimize these small businesses and act as intermediaries to arrange bank loans for growth and sustenance. All very inspiring as I embark on my next social venture abroad.

Nature of Memory

January 12, 2017 – Of Southeast Asia, from Kuala Lumpur

I find so fascinating the fleeting nature of our memory stores. Images, senses and experiences which I have not called up in years come flooding back with the simplest triggers when I travel. Particularly with unfamiliar or infrequently encountered sensations, my brain scrambles to make associations, perhaps to ground my mind and body into my new surroundings. The Bugs Café in Siem Reap immediately conjured up reminiscence of the ground ant coated fish we ate in Oaxaca or the larvae Geoff accidentally ingested in Thailand, when he mistook the honeycomb he was served for actual honey. The blinged-out Cambodian tuk-tuks, no-pun intended, took me right back to Northern India where we guiltily let a geriatric man bike us up an outrageous hill. (Luckily, they are motorized in Siem Reap.) The sweeping frenzy that is pervasive throughout Asia, to keep the constant dust at bay, reminded me of the great pride Cubans took to keep their small patches of land or front stoops immaculate. And certain landscapes instantly harken an inventory of similar features I’ve seen before. As if my brain keeps all waterfalls stored in the same folder, Laos’ cascades brought me back to Bolivia, Switzerland, and of course the Sea to Sky highway in my backyard. The harrowingly steep karsts of HaLong Bay bore a striking resemblance to Norway’s fjords and New Zealand’s Milford Sound. The songs of Cambodia’s monkeys and frogs reminded me of my favorite critters’ croaks and howls in Bali, so much so that just hearing them made me imagine a distant gamelan. And while I’d heard each of the individual auditory elements from Siem Reap’s Pub St. before, its syncopated soundscape of motorbikes, limbless beggars, men hand-churning ice cream, and house music blaring from its street bars was a melange unlike any other. Then, the crowds thousands deep, jockeying at the Angkor Wat night market for a myriad of plastic silliness, fried food or colorful local crafts, took me back to every other Asian market I’ve ever braved. Finally, joining the armies of mostly tourists who flocked to the summit of Siem Reap’s Phnom Bhagan or Luang Prabang’s Pu Si mountain, for the most advantage view of the “best sunset in the world”, felt exactly like the lemmings we followed to do the same in Santorini, Greece or Cinque Terre.

Of course, I know that I may not be doing justice to the uniqueness of each of these places by comparing them so closely. Perhaps, also, this need for recognition defies my ability to fully appreciate their nuanced differences. However, I cannot deny my synapses’ tendency towards such filing. And, admittedly, the fact that land formations and human behaviors tend towards common patterns across the globe actually both touches and comforts me. I am, after all, the daughter of a Jew and a Catholic raised to look more for parallels than conflicts amongst ideologies. So, I won’t resist doing the same when I step in mangy Indian street doggy doo and think that it smells like Yukon husky poop.

Visiting Giants

January 12, 2017 – Of Siem Reap, from Kuala Lumpur

As is often said, travel is about the journey rather than the destination. But some end points are, in fact, the point. And a handful actually do live up to and beyond all the hype. Angkor Wat certainly tops this list. Before we travel to various places, Geoff and I both resist seeing too many photos, particularly of hugely popular sites. And though we could not avoid having seen a handful of images from these temples throughout our lifetime, the extent of their beauty and magnitude remained a secret until we were there for ourselves. It is difficult to put into words the mystique of witnessing her majesty revealed as the sun rose over her five-crowned glory. That we shared this moment with 10’s of thousands of other tourists, mostly Chinese clicking their Canons at a shot a second, took nothing away from this experience I’d wished to have for my entire adult life.

Extra surprising were the uniquely beautiful aesthetic qualities of several other temples in the region. My absolute favorites were the four-Buddha faced pillars that serenely smiled against spotless skies at Angkor Thom.

And as I wound my way around the creepy roots that have strangled but still preserved the stones of Ta Prohm, I felt I was in my own Indiana Jones adventure and am only grateful that they have not let more Hollywood producers co-opt this setting, to let it maintain its mystery for most.

A numbers buff, I also adored the endless layers of wings and corridors at Preah Khan, whose hall of mirrors-like effect gave me the sensation of being embedded in an architectural fractal.

So, for those who shun the roads most travelled, all I can say is that this world wonder is certainly worth shedding a hang-up or two.

New Realities

January 12, 2017 – Of Cambodia, from Kuala Lumpur We are all now bound to each others’ realities in so many ways. Internet, films, and other rapidly spread media images mean that many children in African can recognize Spiderman, and a good number of North American adults can identify a burka, a burrito, or a banyan tree by sight. To me, the Buddhist Tree of Life, pictured below, represents the many intertwined branches that comprise humanity.

These global ties help build empathy and break down “us and them” barriers. However, they also leave increasingly fewer mysteries and surprises. This is why I relish, all the more, those rare new discoveries that travel still sometimes affords, even if the lessons are harsh. The ubiquitous landmine music bands, in Cambodia, were a shocking introduction to the vestiges of the civil war under the Khmer Rouge – thousands of limbless, deformed, blind and deaf performers lovelessly sawed at violins, hammered on dulcimers, and pounded on drums in what appeared to be an empty government gesture to create some kind of paltry vocation for their injured citizens (funded only by the donations from tourists). More cheerful was the realization that Cambodians celebrate their marriages in grand but casual style – up to 50 guests (in everything from jeans to gowns) gather in sprawling outdoor covered patios, over mounds of food and drink, with music blaring from giant subwoofers. One of our drivers taught us that each guest is asked to give an ample minimum contribution, (generally equivalent to $40 USD or more) to cover the festivities cost and to set up the happy couple with several thousand dollars for their new life together.

Solo Travel

January 12, 2017 – Of Cambodia, from Kuala Lumpur

I’ve now been in Asia without Geoff for 4 days, and I’ve been surprised to find myself somewhat disoriented as I’ve proceeded with my trip alone. I’ve done plenty of solo travel before, but rarely have I been “abandoned” part way through a journey. So, even as fiercely independent as I consider myself, I cannot deny that I experienced an unsettling feeling of being untethered when Geoff first left. Of course, as a couple whose greatest compatibility lies perhaps in the way we approach travel, we get into a comfortably flowing rhythm on the road that, as my Grandpa Barron always used to say, “makes beautiful music together.” Therefore, it has taken me a few days to get “in tune” with my new song. To do so, I gravitated to the familiar. My first night I dropped into a hippie bar, where I shared pillowed papasan chairs with chatty foreigners, as we exchanged travel tales over margaritas. Geoff and I crave connection with strangers when we travel, but invariably opportunities infinitely expand when you’re on your own. The crew at the Asana Bar included a divorced American mom who’d taken her two teenage girls out of the US as fast and far as she could, so disgusted by the latest political turn there. She’s got hardly a penny to her name, yet they plan to stay in Cambodia indefinitely, each finding ways to make ends meet (café jobs for the kids, a coop grocery gig for mom, homeschooling and more to learn from the School of Life than any American public school could ever provide.) The coop owners were there too – a gay couple – one guy from Africa and the other from the UK, well settled into a Siem Reap groove. I also really bonded with a French woman who has traveled the globe and worked remotely, for years, as a filmmaker and editor involving local amateurs in her work wherever she goes, and educating them in her art form.

My second attempt to find my own wings, of course, involved a bicycle. I rented a one speed for the day, for 2 bucks, and headed 12 k south of town to check out Tonle Sap Lake – apparently the most fish-rich lake in the world, and a point of pride mentioned by every Cambodian we met. Western ways are the norm in Siem Reap (short shorts and halter tops, beer drinking, and pop music). But I should have known that exposed shoulders and knees (even in 35 degrees Celsius) would get me too much unwanted male attention the moment I was inches from the city boundaries. Nonetheless, this venture let me see working waterwheels, rural villages, rice paddies, my first Southeast Asian mosque and more. My first day on two wheels instead of four served as a healthy refresher course in the mindfulness that solo travel brings. And as I felt my uneasiness begin to settle, I slowly became moored to my surroundings – no longer untethered.

Austerity and Indulgences

January 13, 2017 - Of Transitions, from Kuala Lumpur

That I’m booked to leave for India on a full moon and Friday the 13th certainly adds to my trepidation about the unknowns that await me. But now, as I take my 6th flight in half as many weeks, I marvel at the ease with which most travel plans flow. That I can be walking in freezing rain in Canada one moment, and swimming under tropical sun only hours later never ceases to amaze me. And almost nothing fills me with greater glee than seeing a smiling gentleman in a Cambodian airport with a huge MISS LAURA sign in his hands simply because I sent my hotel an email ride request. I still consider it a minor miracle every time a travel plan actually comes to fruition. And though I’m usually an optimist, I’ve lost enough luggage, missed enough flights, and arrived to enough overbooked hotels to almost expect major mishaps every time I set off on another adventure. But the truth is, almost things actually do work out. And my 90+% successful track record is what gives me the chutzpah to take some leaps even though they still terrify me in certain ways.

Geoff and I like to leave lots of room for spontaneity. So, most of our rooms or internal fights are never pre-booked. But the greatest risks we’ve taken have been during our bike tours in Cuba and Laos, where there was no guesthouse info available en route. And most accommodations were about 50-100 kilometres apart. This was the case when we left Luang Prabang on rented mountain bikes, loaded with only 2 outfits each and a few repair tools for the week ahead. 65 k into our ride, as dusk approached, we had not seen a guesthouse for hours and we could tell form GPS that the next “town” was at least 10 k further. This had me as thrilled as I was scared, while I peeked in the few barebones bungalows that we passed along the road trying to imagine how I might humble myself to ask a local villager if we could sleep on their floor for the night. I’ve met several far braver travelers than I who’d almost exclusively survived this way, and I was always inspired by their courage. So, It hardly seemed a bad last resort. But it was also no guarantee. However, just as dark set in, we came across the sparse Pak Nga guesthouse where we managed a comfy bed and a hot shower in a windowless room for just $3. And again, I percolated with wonder at our fortune.

I’ve also always prided myself on such bargains. And I sort of wear, as a badge of honor, my ability to endure the meagerist of housing amenities on the road. But on the cusp of my 2nd half century of life, with a lower tolerance for undesirable odors, a bum neck that whines without a proper pillow, and ahubby hubby with an excellent paying job and a penchant for good design, I’ve surrendered some of my low maintenance ways. And I must admit that I’ve savored the subsequent perks along the way. In Laos, we scored three different spacious riverfront bungalows with private balconies, daily fresh fruit and bottled water in the room, fragrant toiletries and safes for our valuables. The comfort and security usually still only cost us less than $50 a night, so I could barely resist.

I even got so accustomed to our new standards that I agreed to splurge, for our last 4 nights in Siem Reap, on an $80 room at the incredible Mulberry Hotel, the luxuriousness of which you could probably not book in North America for less than $500. At any rate, accounting was the last thing on my mind as we finished every sweat and dust filled morning temple visit hilling at Mulberry’s glorious pool, surrounded by Buddhas, frangipani, and geckos while we ate complimentary spicy peanuts washed down with tamarind mojitos. The good life is not so bad after all.

All that said, I have only 1 more night of spoiling, at my flutist friend Shashank’s home in Chennai. When Geoff and I stayed there in 2007, we were treated like royalty with 3 multi-course gourmet veggie meals a days, a four poster bed, and a driver. But after their place, it’s back to basics for me, where I’ll share a room with other Child Haven volunteers, sleep on a cot, take cold bucket showers and eat dal for most meals along with the children who live at the home. And, of course, that is all just as it should be, and I plan to relish such immersive living. But of course, I hope my tangled curls, my belly and my cervical spine have not become too “soft” to handle it!

on their floor for the night. I’ve met a few far braver travelers than I who’d almost exclusively survived this way, and I was always inspired by their courage. So, It hardly seemed a bad last resort. But it was also no guarantee. However, just as dark set in, we came across the sparse Pak Nga guesthouse where we managed a comfy bed and a hot shower in a windowless room for just $3. And again, I percolated with wonder at our fortune.

Loss

January 15, 2017 - Of Sparks and Wings, from India

This was far from the entry I imagined I would write today. I have arrived at Child Haven International, in Kaliyampoondi. The distorted sound system of a Tamil film blares across the dirt field of the Home, no longer filled with young cricket players because they are all riveted to the screen inside their dining hall. This special form of entertainment is their treat for the occasion of today’s holiday, Pongal, Tamil Nadu’s harvest festival. Rangoli designs adorn the concrete foundations of the campus buildings, each chalked in multi-colors to create the beautiful mandala-like designs that honor this festival. And yet I struggle to feel festive today, despite the hugs and kisses and hand holding that every child and staff member greeted me with upon my arrival. Because they should be showering Maggie too. But instead, in a tragic turn of events, she is on a plane headed home after receiving the shocking news that her father suddenly died of respiratory failure on a jungle trek in Peru. We were apart when she heard, awaiting our rides to the Home from separate friends’ places in India. She learned over Facebook – something no daughter should ever have to experience. I learned on a video chat with her, while long pauses and glassy eyes showed how little either of us were able to truly process this.

Morton Winston was an exceptional man, and while we are often inclined to say that of people once they pass – with him it is entirely true. For years, he served as the President of the Board of Amnesty International. Maggie was raised in a family that, at times, harbored Burmese refugees; at others, spent years abroad helping the unjustly served in Nepal, Thailand, South Africa. Though little can be of solace in the wake of such a loss, I have to hope that her father’s adventurous soul would have wanted to come to rest in a place as wild and wonderous as the Amazon. Inspired by her father’s example, intrepid travel and community service have been second nature to Maggie. Morton also married into a remarkable family of women, each power house arts activists in their own right. Together, they have collected Canada Council honors, film and dance awards, and accolades too numerous to mention. Maggie always jokes about holiday family dinners, where simple “what’s new?” catch-up conversations rival Nobel Peace Prize presentations. And in keeping with this generosity of spirit, amidst her moment of crisis, Maggie still managed to secure a fellow theatre artist, living nearby in India, who could take her place as my collaborating facilitator for these two weeks. She said she found it a helpful distraction while she could do little for 2 days as she waited for her changed flight to depart. I am deeply grateful to her for this gesture. I will meet Kaeridwyn for the first time tomorrow, where she lives in the intentional community of Auroville (below) – perhaps one of the most sustainable and successful of its kind in the world. Since the 70’s, this non-denominational autonomous society has grown to a thriving community of 5,000 from over 50 countries. I relish the chance to learn about her alternative living, and to learn from her artistic expertise in physical theatre and some of her own forms of puppetry.

How ironic though that, only two entries ago, I marveled that most things actually do go to plan. Yet, of course, I’m now harshly reminded that this is only true except in those 1 % of times when they absolutely do not. As I sit alone in the Home’s library, digesting this sad and sudden change of plans, wondering if I can still be of true value here, I pass the day reflecting and reading, as I will do until our project begins on Tuesday. And here, I quickly came upon several texts, left by former volunteers, which my intuition somehow knew I needed to discover.

· A Tagore verse: “The butterfly counts not months but moments and has time enough.”

· Gary Zukav’s Soul Stories that claims “the journey of a hawk depends on both the hawk and the wind. Sometimes the wind takes the hawk where it wants to go, and sometimes it doesn’t. When it doesn’t, the hawk doesn’t mind. Either way, hawks are masters at flying, always in control of their own wing and tail feathers. This is what elegant spirts do.”

· And the charming biography of Child Haven’s founder, Bonnie Cappuccino, written by her “long-suffering” husband Fred. They opened their first of nine homes and schools (serving almost 2,000 youth in India, Nepal, Bangladesh and Tibet), 30 years ago, at the ripe young ages of 53 & 60, after raising their own 21 children into adulthood (19 of which they adopted). For their astounding efforts they have received the Order of Canada and a UNESCO Human Rights Award. Their inspiring book’s final words read: “Glowing deep within each one of you is a divine spark. Some of you may be skeptical, or feel you are unworthy, yet the divine spark glows. This divine spark may surprise you as the future unfolds. It may lead you to risk much in some wild act of compassion. You are of infinite worth; you possess a dazzling beauty that is irresistible. Trust this divine spark glowing in your deepest being.”

Thank goodness Bonnie trusted hers. And thank goodness the wind seems to have been on her side when she’s needed it. Not when they found a brain tumor that paralyzed the right side of her face. Not when one of her treasured children committed suicide. But certainly when her second cancer surgery succeeded. And several times, when she has managed to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles, immigration nightmares, civil wars, natural disasters and more to create and sustain Child Haven’s nine thriving homes. Bonnie was on the Air India plane that left Montreal in 1985, crashing and killing 190 people. Only she took its incoming flight to YYZ, before those fated passengers boarded on their way to London. The wind was with her that day. It is hard to understand what the wind intended for those 190 others. None of us can ever answer such questions. I guess we can only keep flying and continue to be the master of our own wings.

Wayfinding

January 19, 2017 Of Kuala Lumpur, from Pondicherry, India

After Cambodia, Air Asia’s wings took me to Malaysia for an extended layover before my India project began. My whirlwind arrival reminded me that finding my way in a new surrounding is one of my favorite travel pastimes. I landed at the Kuala Lumpur airport solo, soared through immigration, collected my luggage, scored local currency from the airport ATM, located the train terminal, successfully navigated the ticket machine, boarded the correct train, managed a station transfer without a hitch, and then walked straight to my hotel front door, all in just one hour. My feat gave me a rush equivalent to winning the Amazing Race. But thanks to GPS and surprisingly clear wayfinding signs, this was actually quite doable and not really as impressive as it might seem.

For my first night, I stayed in the commercial district of Bukit Bintang, in the heart of the city just meters from the fabled Petronus towers. On first glance, downtown KL appears nothing but a conglomeration of neon, highways and malls. The latter rival the opulence of Fifth Ave, with marble floors, high speed escalators, and posh stores like Prada and Sephora, built in post-modern architectural style. But no amount of polish is able to hide the same litter, sewerage stench and stray dogs that one can find almost anywhere in Asia.

My Canadian friend and Malaysian resident, Lisa Sauer let me know that her new home is a nation rapidly striving to attain first world status, but too fast for its capacity. Thousands of luxury high-rise condos stand empty, built over-ambitiously and without proper amenities to service them. A government program to mass distribute Western toilets throughout the country has dramatically failed to meet its targets. And an ever-increasing disparity of wealth keeps many still living in squalor while others enjoy every continental comfort. Craft beer, high speed wifi, pools and tennis courts in most middle to upper class apartment buildings, quinoa and kale smoothies at Whole Foods-like grocery stores, and even flat whites at Aussie-inspired cafes are the norm in the mostly ex-pat neighborhood of Mont Kiara, where Lisa generously hosted me for my final three nights.

Such economic imbalances trouble me, just as they do at home. But I can’t deny that a few more days of indulgence did provide a welcomed breather for me as I prepared for the intensity and austerity of India. And I can certainly understand the appeal for many to stay in this city, surrounded by the familiar while still only a $100 flight from an endless stream of exotic destinations. Lisa and her partner Jeff are able to spend long weekends in Bali, have Christmas holidays in New Zealand, and take quick jaunts to Hong Kong with the ease of a trip from Vancouver to Seattle. It was a privilege to witness the full life that they’ve carved out for themselves there. It was also a treat to discuss books, share concerns and criticisms of “the orange man who will remain nameless”, and to swap travel highlights and travails. Lisa is the most intrepid person I know. She can only keep track of the countries she has NOT visited, because this list falls only in the single digits, while the count for those hundred plus principalities that she has experienced keeps changing with history’s shifting geographical borders. Though a rhythm-loving musician and chronic counter myself, I have resisted the urge to innumerate my own travel destinations, for years, realizing that a qualified life is always more well-lived than a quantified one. However, I learned in Morton Winston’s obituary that he always aimed to visit more countries than his current age. And that someone as substantive as he set himself this challenge gave me permission to do so as well. So after my own tally, I realized that Lisa’s new home marked 46 for me, leaving me close to my new 50 by 50 goal, with only 16 months to go. If all goes to plan by then, I’ll make it to Brazil for another school project, to Nicaragua for some Spanish practice, to Australia to teach some university Art for Social change workshops, and finally to Burma, where I will sail with several of my best buds to mark my passage into the second half century of my life. But I’m also open to wherever the wind might take me…

Imprints

February 8, 2017 Of India, from Vancouver

One week after my return to Vancouver, I stare at the red faded swirls on my left palm, willing the mendhi design to last just a bit longer, in much the same way I strive to keep the lessons of my trip alive. I can still practically count the hours since 15-year old Sangitha, one of our most keen Indian students, artfully applied the henna to my limbs on my last night. Yet, I can already feel the glow of my skin, the bloom in my heart, the sparkle in my eyes starting to dim despite my best efforts. I remember when I attended the Dalia Lama’s 10-day Kalichakra teachings, in Dharamsala in 2007, and I finally understood why people go to church. Between five daily hours of exposure to his wise words, 10,000 global visitors engaged in high-minded discourse at every café, hostel and momo shop, inspired to live better, be better. I got caught up in this too. But with every passing day after leaving his Himalayan refuge, my behavior slipped ever so subtly, and I wished I could be in the presence of his radiance yet again. I needed the nudge that I now realize church provides for the most earnest seekers, whatever their faith.

Like then, for two weeks in Kaliyampoondi, I easily relinquished coffee, alcohol, cursing, and even ill thoughts of others while I was immersed in my purposeful existence there. But it took only two days home for a Canadian friend’s “us and them”ing of Americans, (the very same dangerous thinking that led “the despot who won’t be named” to implement his dreaded immigration ban), to set me off into a temperamental rage, the negative effects of which lingered for several hours. Gone seemed the equanimity and compassion that so grounded me when I faced numerous cultural differences in India and throughout my trip. Only a day later, a string of unnecessary expletives escaped my mouth after a simple computer glitch, as I mourned for the analog-nature of my intimate face-to-face Indian exchange. And finally, a third Saturday night cocktail, sipped only out of habit not need, had Geoff and I walking home from a dinner party on separate sides of the street over a trivial thing I’ve already forgotten.

Art is my temple. And the privilege to witness its transformative power, despite language barriers and gaping cultural differences, is what nourishes my soul. There is also something undeniably sacred about India. Beneath the cow dung, beyond the open sewer stench, besides the archaic gender dynamics that still perpetuate inexcusable oppression and violence towards women, there is a palpable grace. Just to watch the sincerity in the Child Haven kids’ closed eyes and furrowed brows as they chant their simple pre-meal prayer is to truly know this. I was reduced to tears, daily, by similar profound expressions of spirituality. Indians also bring exquisite beauty and ceremony to every occasion, as seen in the stunning saris that Child Haven students wore for their Republic Day school dance performance.

In only my two brief weeks there, I experienced 5 state holidays and 4 additional rituals for special occasions at the Home. Pongol is South India’s harvest festival. And I was treated to its chromatic splendor the instant I landed. I arrived in Chennai just prior to midnight, terrified that there would be some grave error in my visa-upon-arrival form, and that I’d have no way to get cash for a cab. I’d heard that India’s prime minister had taken 5 & 10 thousand rupee notes out of circulation to prevent black market counterfeit. Consequently, this had left the country with a currency crisis and practically no working ATM’s as they scrambled to print more small denominations. However, to my surprise, I waltzed through immigration in a record 5 minutes (faster than YVR), and successfully exchanged my last $100 USD for 4,000 rupee (a crap rate since the Global Bank quoted 6,000, but I was happy to take anything at that point). Then, I braved the sea of pre-paid taxi stands to secure the best deal, proceeded to be accosted by a team of drivers jockeying for the right to my fare, and chose the most geriatric of the bunch figuring he was my safest option. I gave him the address of my friend Shashank’s posh neighborhood which he pretended to recognize. But of course, he proceeded to stop a half dozen times for directions. Luckily though, Pongol had most families still up at that hour, diligently chalk-painting their stoops with amazingly symmetric Rangoli mandalas. This vibrant display of communal art-making let me know I had, indeed, arrived in India. And she instantly got under my skin.

Detours

February 8, 2017 Of India, from Vancouver

Geoff and I stayed with Shashank exactly ten years earlier, mid-way through our year-long trip around the world. We’ll never forget our lively discussions with his family, about art, politics and travel. And we can still taste the epic 6-course meals that his mother and wife prepared for breakfast, lunch and dinner every day, as they did on this visit too. That Shashank is also a world-renowned Karnatic flutist only added to the richness of our visit, as we were treated to daily rehearsals in his living room. And this time, his ten-year old daughter Swara (aptly named after a musical note, and still in Siri’s belly last we came), was the one displaying her own virtuosity on the blues guitar.

But sadly, it is the Skype call that I had with my dear Flagstaff colleague, Michael Sullivan, on that first morning in India, January 15th, 2007, which I most remember. With shock and horror in his eyes, Michael revealed to me that he had just learned he had a terminal bone cancer, the ravages of which took him before we even returned home in June. So, a mere glance at Shashank’s desktop computer made me long for my friend. How odd, then, that it was on that very same screen I read Maggie’s message about her father’s death, again on my first morning at his home, this time on January 14th, 2017.

And so the detours began. Maggie’s to Baltimore, and mine to Pondicherry and Auroville, to meet my new artist partner, Kaeridwyn, where we’d revise a plan that would best align with our complementary skill sets. Of course, our sessions had been scheduled to begin on Monday, but as has seemed to become the norm on these global projects, the Child Haven director neglected to mention that Pongol celebrations continued through Tuesday evening. To lose 20% of our scheduled 10-day engagements would have normally set me into a panic. But instead, I seized the opportunity to pivot, explore another Indian destination, and bond with my new colleague. That I also fit in long walks on Pondicherry’s seaside boardwalk, marveled at parades of sari-clad women in their holiday finest, visited their Ghandi statue, and enjoyed one more night in a cush b&b was only a bonus. But I’ve come to appreciate that detours are always full of such perks.

Silverware and Other Taboos

February 8, 2017 Of India, from Vancouver Another of my favorite aspects of India is her cows, who roam her city streets, lighten her chai, and transport her people and goods. Cows were the talk of the town during my visit, as the state had just outlawed the ancient Pongol practice of jallikattu,which is South Indian’s version of “running with the bulls”. So, while blue Americans and their global peers hit the streets to protest the horrifically racist policies of the “man who shall not be named”, Tamil Nadu’s streets were alive with their own activists. But these were not the PETA version that one might expect (animal-lovers standing up to support the abolishment of a practice that is cruel and violent to the bull, and which kills several bold and foolish men each year). Contrarily, the prevailing sentiment of the protesting citizens (largely university students) favored the maintenance of this ritual, as these deeply traditional people feel their government too often threatens their ancestral connections. As I’m partial to protecting animal and human rights, I was, no doubt, very surprised to learn about the nuances of this controversy. But I realized I was ill-equipped to understand such a complex and age-old battle.

I was born in bovine country myself. And cow-tipping was a high school pastime for me and my friends. But our version involved only a harmless ringing of their bells, rather than a full body topple which I’d learned some rural US farm kids preferred. For most Hindus, cows are sacred, revered for their gentle nature and agricultural assets. Perhaps this, too, inspired me to become a vegetarian as well as an ice cream fanatic by a very young age. I virtually started my career in the industry, with jobs in five different parlors between the ages of 13-20. With such a shining for these adorable heffers, I also invariably took a preponderance of cow photos on my routine bicycle excursions to neighboring Uthiramerur. Most amusingly, Indians paint the horns of these honorific beasts for Pongol, the brilliance of which lasted throughout my fortnight. And while close sleeping proximity to animal feces is not usually something I would celebrate, I was actually comforted when a Child Haven staff first walked me to my room and I was greeted by the Home’s five dairy cows whose pen was just five feet from my door.

Eating meat was the easiest of India’s taboos for me to avoid. But their other eating practices took more getting used to. In keeping with the rock-hard mattress that I slept on, our meals were served on the floor of a giant chairless, concrete dining hall. So, three times per day, I joined all 250 children, 30 staff, and a half dozen other volunteers as we ate cross-legged and with only our hands to ingest the splendor they served us each day. The puffy rice flour dumplings, called idly, which the cooks miraculously prepared by the thousands to perfection, were the easiest to eat without cutlery. But rice with spicy mango stew, chickpea curry, or ginger chili pesto posed tougher challenges. And I found that tearing chapati (their rice flour pancakes) one-handed was the trickiest feat of all. But, of course, this was essential because their lack of toilet paper meant that all self-cleaning was done with the left hand, leaving only the right free for dining. However, whatever discomfort these new habits caused became quickly overshadowed by the children’s infectious joy and gratitude during meals.

Adapting to their dress code, though, did not come as rapidly. Kaliyampoondi is located deep in traditional Southern India where gender roles are clearly delineated. The public domain is largely male, and the home female. Throughout rural Tamil Nadu, girls and boys sit on opposite sides of their school classrooms, as they did in the dining room at the home. This persists despite Child Haven’s strongly imparted Gandhian beliefs of gender equality which result in their generously funding every single child’s university tuition (male and female). However, in keeping with such contradictory divisions, we were only allowed to work with each gender in separate sessions throughout our project, and this led to a variety of interesting observations. While boys wore short-sleeved button down shirts and tailored pants to school, and then changed into Western shorts and t-shirts for afternoon play, girls (by the age of only 10) had to wear chudigar in most contexts. This oppressive uniform included large, knee-length, polyester shirts with baggy pants and an additional shawl (or dupita), carefully pinned to their shoulders to cover even the smallest bloom of a bosom. Additionally, these heavy layers are worn throughout the year, which peaks to 120 Farenheit in the summer months! And girls had to wear similarly unrevealing clothing around the home, even as they ran 800 metre dashes in preparation for their State-wide Sports Day competition, which was scheduled for my departure day. Here they are with my new buddy and volunteer, Andy Rush, as they arrive home on the new bikes that every Grade 11 child was gifted under a special government program.

This dress code was also enforced with female volunteers at the home. And though I am eager to honor foreign traditions when I’m abroad, it was difficult to abide, while I watched male staff and volunteers wear jeans or whatever else they liked. Some even enjoyed topless morning runs. However, what I found most disturbing was the community policing that the girls did with each other, as well as with the volunteers, to adjust a slight slip of the shawl or accidental exposed bra strap. Of course, I was keen to avoid being corrected or perceived as disrespectful in any way, so I soon found myself routinely fussing with my own scarf. And I quickly came to imagine the body shame and self-consciousness that these strictures could breed. Consequently, it became highly evident that the boys exhibited far greater self-esteem and exuberance, as well as a willingness to improvise and be playful. That said, I was amazed how much the girls’ confidence grew throughout our project. So, I soon forfeited my inclination to fight such bewildering practices, and recognized that my time would be better spent focusing on scalable transformative change through our arts engagements rather than on massive systemic change.

Superheroes

February 9, 2017 Of India, from Vancouver

Inspired by the ideals of Mahatma Gandhi, Child Haven International was founded in 1985, by Bonnie and Fred Cappuccino, the superhero couple that I previously mentioned. Their non-profit has built nine healthy, sustainable homes for almost 2,000 children and women in India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Tibet. And each of these “havens” provides food, shelter, clothing, health care, educational and moral support for their residents. Most children go on to pursue post-secondary education, and Child Haven even funds their university tuition. The homes are fully run and staffed by locals, along with a handful of volunteers from abroad (largely Canadians). And Gandhi’s principles of gender equality, no caste (or class) recognition, non-violence and vegetarianism, simple living, as well as respect for all religions and cultures breed a positive, life-affirming energy that I felt during every moment I spent at their homes in both Kathmandu (for a 2015 arts project) and Kaliyampoondi. This fertile ground provided the ideal environment for our arts engagements. So, it is no wonder they resulted in, perhaps, the most impactful project for Instruments of Change, to date.

Amidst cicada and frog song, morning starts at Child Haven with the children’s 5 am wake-up bell which elicits an occasional bark from Puppy, the resident dog. As the children are meticulous about cleanliness, they proceed to pridefully brill cream and braid their hair, wash their bodies, and press their uniforms to perfection. These thorough ablutions are followed by meditation, non-denominational chanting, and a jog around the large grounds of the home. Then, they queue up for their daily protein, a sweet, warm cup of soy milk, made from soybeans that are crushed, right there on the property, by the machine they affectionately call the “soy cow”. They form similar lines to receive breakfast, lunch, snack and dinner, and this 300+ person dance proceeds with remarkable order.

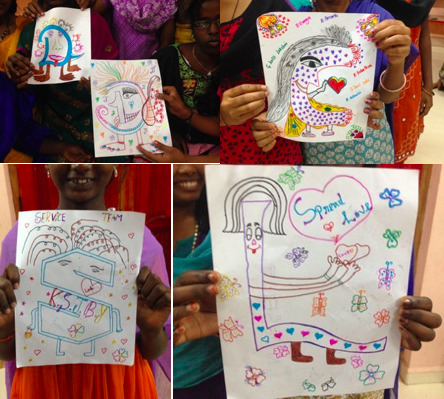

In fact, observing these young people choreograph their shared space, day in and day out, was perhaps the most moving part of my experience there. In the spirit of simple living, each child’s entire worldly possessions (clothes, shoes, jewelry, toys, toiletries, photos) fit into one small metal suitcase. Consequently, there is little sense of “mine, mine, mine”, just like we witnessed in the Nepal home. Throughout our project, the children cooperatively shared supplies, decorations, and tools without incident. They were equally gracious about returning things promptly, in good condition and exactly where they found them. Our limited stock of erasers presented the only sharing challenge, as they took the same pristine approach with their work as they take with their appearance. Of course, we are always careful to dispel notions about “right or wrong”/”good or bad” art in our projects. But habits run deep. So, there was nothing left of our 10 inches of rubber erasers by the end of our two puppet-designing sketch sessions. However, their diligence certainly paid off, as seen by these fanciful characters that they created.

During our project, entitled Repurpose Our Purpose, we asked kids to express their feelings about their own unique value and purpose (or, in other words, their superpowers), through story and song. At the same time, they harnessed the value of everyday objects and trash by repurposing these materials to make puppets and instruments for a final original theatre piece. And finally, we introduced a variety of interdisciplinary collaborative activities designed to cultivate an appreciation for the power of a collective sum that is greater than its parts. The first of these exercises asked students to identify with certain Jungian archetypal personality types (IE. Jester, Creator, Explorer, Sage, Leader, Caregiver, Innocent, Hero, or Rebel). Then, we organized them according to their chosen type, and these became their working groups for the duration of the project. Subsequently, they performed physical gestures that represented their Archetype’s character, demonstrated by our Boy Jesters, with their thumbs to their noses.

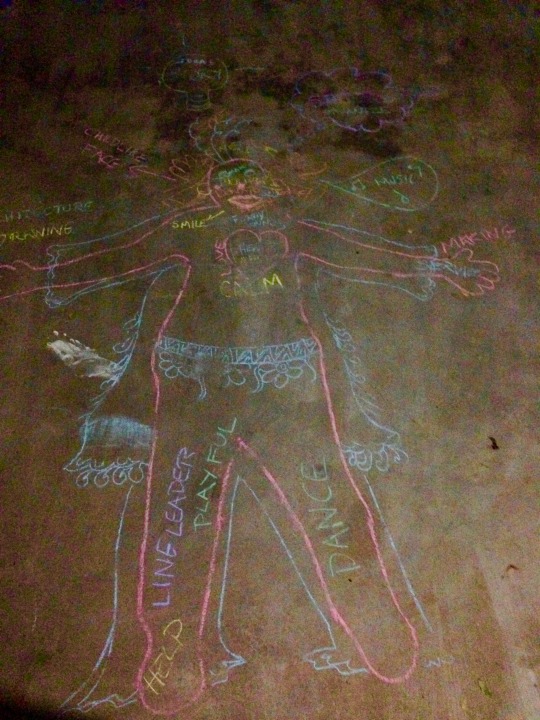

They also collectively brainstormed a vocabulary of words related to the assets of their chosen superhero characters. And while we relied heavily on the excellent translation provided by 4 helpful staff members, Ganesh, William, Johnson, and Poppy, this activity revealed that the students had a stronger command of English than we had realized earlier in our project. Below are their own words, placed anatomically correctly, on the Body of a Superhero that they chalked on their playground.

Ultimately, each archetype group chose the most resonant word to describe their character’s superhero, and the first letter of this word became the body shape for their puppet design (IE. M for Meditation as the Sage’s superpower, and D for Dance as the Creator’s superpower). Then, they brought these creatures to life using reclaimed cardboard, bicycle tires, scrap paper, styrofoam and newspaper waste. Predictably, their creations were full of saturated color and ingenuity, as is everything in India.

And the designs did not divide along typical gender lines, as the sweetness of this Caregiver Boys’ heart-balloon covered puppet illustrates. These resourceful children also took the upcycling aspect of our project to a whole new level as they proceeded to cut scrap gold metallic paper into hundreds of tiny bits to make their own glitter!

To further develop narratives for their characters, we presented the children with a scenario (much like a videogame simulation), where each puppet (1 per archetype group) had to collectively pass through a series of obstacles. However, we set the rule that each challenge could only be solved using one of the puppet’s superpowers, (referencing the idea that the whole is stronger than the sum of its parts). So, each archetype group invented both an appropriate problem and a solution with which their superhero could “save” the day for all their peers. The girls and boys created separate narratives, each with their own host of diverse characters. And some of their most memorable storylines were when the Boy Sage taught everyone to meditate so they could levitate over a cold, impenetrable river; and when the Girl Creator drank a magical chocolate soy power drink after all the puppets became immobilized by the scorching sun. Then, she led them all in a dance that revitalized their energy. These are both, interestingly, very Indian solutions. I was also thrilled to learn that the Boy Hero group chose Music as their super power. In their creative storyline, after the whole puppet group gets trapped in a house, set ablaze by fire, the singing hero puppet plays his guitar and the musical notes that emanate from it magically transform into water that puts out the flames. Additionally, to develop their dramatic skills, Kaeridwyn led the kids in found object animation activities. Below, they are enacting a “fart” scene (or “susu” in Tamil). It was, of course, heart-warming to see that adolescent poop jokes transcend cultural boundaries. And clearly, our young-at-heart translator, Johnson, thought so too.

Here I am listening intently to the Boy Leader’s plan out their scene.

And this is Kaeridwyn directing the whole crew of boy puppeteers in their opening scene.

Over two weeks, we were allotted one hour per day with each gender group. However, the children were so invested in our project that they went over and above the call of duty, spending several additional hours writing their stories, practicing their actions, and fabricating their puppets. This is exactly the ownership we always strive to cultivate in our work.

We also put in our fair share of extra time, administering puppet triage and other vital work, graciously helped by Jackie, (in the back of the photo below). It was incredibly fortuitous that she and her husband, Andy (in the bike photo from Feb. 8th’s entry) happened to be volunteering during our visit, because they are, respectively, a retired music and English/drama teacher. They supported nearly all of our sessions with their expertise and cheery presence, and Kaeridwyn and I could not believe our good fortune to have their help.

For the music component of our piece, the kids brainstormed about qualities essential for good team work. Then, we analyzed the musicality of this language by breaking the words into rhythmic syllabic categories, according to spoken stresses (IE. Re-spect; Leading, Sharing, Kindness; Unity, Confidence, Discipline; Following; Concentration; Cooperation). These evolved into both chants and drum beats that they performed with their voices and found object instruments. To warm-up these budding percussionists, we used stray firewood for sticks and turned their playground into a drum kit. And for their instrument scavenging, which I’ve previously led in Vancouver alleys and Kathmandu streets, we had to go no further than the grounds of the home itself, for they had a plethora of sonorities right on the premises (10-gallon water jugs for drums, empty 10-litre bottles and beans for shakers, damaged tin plates and cups for cymbals, and giant 5-foot rice barrels for bass drums).

A most boisterous time was certainly had by all. And we’ve received reports that the children have continued to chant the lyrics around the home, since we left two weeks ago. Another legacy of our project has been the re-mount of their puppet show for Bonnie, when she visited just one week after our departure. Their sports director, William, had so skillfully translated for us, that he was able to hold up the fort by himself, rehearsing and directing their repeat performances. Jackie sent me this photo of all the kids’ animated faces while they sat through the entire hour-long show for the second time.

Excitingly, the children may even get a chance to “take it on the road” if Kaeridwyn succeeds in securing them a showcase at Auroville’s Upcycling Festival in mid-March. It is this kind of sustainability that we aspire to achieve in all of our work. But the nature of two-week arts engagements run the risk of merely serving as “hit and run” projects, particularly with communities who have little additional exposure to artistic activity, like in Kaliyampoondi where their schools’ rigorous academic expectations emphasize a STEM rather than a STEAM (Science, Technology, English, Arts, and Math) curriculum. In fact, on top of their 6-hour school day, Child Haven kids diligently study at least 3 more hours per day. We even witnessed those approaching state-wide exams (Grades 10 & 12), downing chai until the wee hours of the night to pack in a few extra hours of study. Academics aside, there was at least one artistic discipline with which the kids had lots of experience - dance. That’s because they are treated to a Tollywood (Tamil Nadu’s version of Bollywood) film every Saturday night, and they’ve memorized the moves from all of their favorite scenes. So, we knew we had to end each of their puppet shows with a dance number.

What we never could have counted on, though, was the spontaneous eruption of all 250 kids in the audience, when they began to dance along, after the boys’ last piece. The enthusiastic Director of Child Haven, Ganesh, consistently voiced how impressed he was by the efficacy of this type of arts-infused learning. In fact, he was the one who made the final call to keep the Tollywood music blaring after the show, lending itself to what we learned was the first ever time that Child Haven boys and girls danced together in one room, at the home. So, maybe systemic change is not impossible after all.

In addition to the meaningful encounters that I had throughout our engagements with the children who participated in our program, there are so many moments I keep returning to, now that I am home. Showers of hugs and nose kisses from kids young and old, never too-cool-for-school to demonstrate their appreciation, as many adolescents at home would be. Afternoons, sitting with the other volunteers, on the kitchen’s dirt floor, thumb wrestling, hair braiding, bean cutting, and playing paddy-cakes with the kids. And 7 am theatre games with the irresistibly adorable littlest ones who were too young to participate in our main project.