Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Slavery in the Dar al-Islam

Slavery is a word which, in the context of the modern Western (and particularly American) world, carries with several disturbing connotations. This is due to the recent Western experience with slavery through the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Among these bequeathed sentiments are: exploitation, the complete stripping of self-determination, and severe racism. Though all of these are somewhat present as themes in Medieval Middle-Eastern history, these connotations are overly harsh in the context of the Medieval Islamic world. These connotations are particularly inaccurate in regard to the Mamluk phenomenon.

There was certainly a certain amount of exploitation within the Mamluk system. However, not in anywhere near the extent present in the post-Enlightenment American context. Mamluks, for a start, were not completely beholden to the will of their owner. Partly, this was because Mamluks were usually a collective. They were bought and sold together with other members of their tribe. Because of this, their owner had to take into account the sentiments of the entire group before rendering any punishment or reward upon any specific individual. Thus, when a Mamluk corps felt mistreated, they often, as a group, left the household of their master. In having the ability to do so, Mamluks also had some measure of self-determinence (albeit, in a collective sense). Therefore, the common conception of slaves as being unable to shape their own destinies is demonstrably not applicable here.

This phenomenon plays itself out most often in Egyptian history. This has lead to scholars having a wide repository of textual evidence for the often non-exploitative nature of the Mamluk system. Therefore, engaging in extreme exploitation was, most of the time, simply untenable in the Middle-Eastern context.

The resistance to domination of the Mamluk classes led to many negative psychological conceptions of them in the Medieval Muslim mind. As Miller states, “The most potent characteristic, the most dangerous characteristic of the slave was precisely that he fell between categories, into the "interstices of definition" where power, negative or positive, inheres” (Miller 593). Miller, here, is speaking more broadly. However, her basic intuition holds true in a wide sense. Arab non-slaves were caused no small measure of psychological stress due to the incongruence of slaves who held temporal power. This uneasiness, bordering on fear, of the Mamluk manifested itself in unpleasant ways. For one, due to, as Miller points out, slaves being traditionally psychologically associated with death, the Mamluk, in their capacity as soldiers, rationalized as appropriately possessing the authority to deal death upon others. Those this may, at first, not seem to be an entirely negative conception, one must also consider the implications: for one to be conceived of as already dead (in a sense), one must first be conceived of as lacking the virtues of the living. Thus, Mamluk slaves were seen as lacking the humanity inherent in the other social classes.

For another, Mamluks were often ostracized and kept at an arm’s length from normal Arab citizens within the state. This ostracization was made easier by the fact that Mamluks were almost always from the frontiers of the Islamic world (Miller 597). Most often, Mamluks hailed form the various Turkistani regions of Central Asia. Often, they were taken in the course of warfare and made to transition from POW to slave-soldier. But, interestingly, many Mamluks also chose to sell themselves into slavery. We may posit that they did this for a couple of previously mentioned factors.

1. They coveted the power granted as a matter of course to Mamluks.

2. They coveted the security, whether in terms of food or protection from old enemies, the Mamluk institution provided.

However, Mamluks were not the victims of systematic racism. Drawing on the Islamic philosophical idea that all peoples of the world have a certain character, determined by the clime from which they hail, Mamluks (almost entirely consisting of Turks) were postulated to have a variety of positive characteristics: loyalty, bravery, and toughness/resilience (For more information, see Hillenbrand. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. ch. 5). This philosophical system also ascribed some negative attributes, like lack of intellectual curiosity and irritability, but this was not an entirely damaging stereotype. These traits, interestingly, were not considered wholly bad traits for one with military power (like a soldier or monarch) to possess. Thus, though Mamluks were subject to racism, they were not necessarily victims of it.

Works Cited

Hillenbrand, Carole. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012.

Miller, D. A. "Some Psycho-Social Perceptions of Slavery." Journal of Social History 18, no. 4 (1985): 587-605. doi:10.1353/jsh/18.4.587.

0 notes

Text

Bibliography

Abu Dawud, Hafiz. Sunan Abu Dawood. (~850 CE).

Ard Yasht Avesta. (~200–600 CE).

Bosworth, C. E. “The History of the Saffarids of Sistan and the Maliks of Nimruz.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 59, no. 02 (1996): 380.

Cohen, Mark R. Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Cook, Micheal. Muhammad. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Donner, Fred M. Ibn ʻAsākir and Early Islamic History. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 2001.

Drory, Rina. “The Abbasid Construction of the Jahiliyya: Cultural Authority in the Making.” Studia Islamica, no. 83 (1996).

Hagler, Aaron. “The Shapers of Memory: The Theatrics of Islamic Historiography.” Mathalno, 5, no. 1 (2018).

Halm, Heinz, and Allison Brown. Shia Islam: From Religion to Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1999.

Hillenbrand, Carole. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012.

Hodgson, Marshall G. S. “How Did the Early Shîa Become Sectarian?” Journal of the American Oriental Society 75, no. 1 (1955): 1. doi:10.2307/595031

Maalouf, Amin. The Crusades through Arab Eyes. New York: Schocken Books, 1985.

Miller, D. A. “Some Psycho-Social Perceptions of Slavery.” Journal of Social History 18, no. 4 (1985): 587-605. doi:10.1353/jsh/18.4.587.

Schiltberger, Johannes, and J. Buchan Telfer. “Bondage and Travels of Johann Schiltberger.” 2009. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511697593

Sizgorich, Thomas. “Narrative and Community in Islamic Late Antiquity”. Past & Present, No. 185, pp. 9-42. (2004).

Sullivan, Nate. “Post-Modernism & Historiography in the 20th Century.” Study.com. Accessed September 19, 2018. https://study.com/academy/lesson/post-modernism-historiography-in-the-20th-century.html.

Tajddin, Mumtaz Ali. "Jahilliya.” Ismaili.net. Accessed September 18, 2018. http://ismaili.net/heritage/node/10495

Tavadia, J. C. “A Rhymed Ballad in Pahlavi.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 87, no. 1-2: 29-36. (1955).

Wallis, Wilson. Messiahs: Christian and Pagan. Hardpress Publishing, (2012).

0 notes

Text

The Dhimmi

The Christian and Jews (along with, at times, Hindus, Zoroastrians, Buddhists, and Jains) of the Medieval Islamic world had a varied lot. Designated as "People of the Book" or Dhimmi, in Jurisprudencial terms, the non-pagan subjects of Middle-Eastern states were, in some places, such as early Medieval Ummayad Iberia, treated as near equals. As evidenced by the success of such scholars as Maimonides, it was sometimes quite possible for non-Muslims to find a great measure of success within the Islamic word. At other points, such as during the time and reign of Almohad caliphs, this state of affairs was reversed. Muslim rulers in the same vein as the Almohads often sought to Islamicize their lands. Thus, the dhimmi (and their protected status) presented a problem for such rulers. Interestingly, Maimonides' life gives us an example of both of these sentiments. Early in his life, Maimonides was able to progress far in the grand city of Cordoba, finding success as, first, a rabbi, then, a doctor. He did this under the rule of the Almoravid Sultanate. However, when Cordoba was taken by the Almohads, whose state was characterized by fanaticism and intolerance, the dhimmis residing therein were forced to convert, die, or enter into exile. Thus, due to Islamic religious persecution, Maimonides was forced to leave his home (Cohen xvi). Other, less dramatic forms of oppression were also extant in many lands. Due to Prophet Muhammad's directive against making Muslims slaves, the lion's share of the slave population in lands, such as Egypt and Asia Minor, were from a dhimmi background. Ironically, many of the enslaved were then forced or strongly encouraged to convert to Islam. Thus, even the most basic protections traditionally granted to the dhimmi (lack of compulsion in religion) were sometimes taken away.

Another important point to be examined within any discussion of the dhimmi is that of the Jizya tax. What is often misunderstood about Muslim/non- Muslim relations is the intentionality behind the imposition of the Jizya tax. Often, it is construed and presented by non-Muslims (most often in the West) as malevolent and a deliberate, vindictive, and resentful move to punish non-Muslims for their ignorance. In reality, however, the Jizya, speaking purely on the intentionality behind its implementation (we shall next address the morality of its de-facto consequences), was imposed as a mercy upon the dhimmi. The evidence for this is to be found in the fact that, with the placing of the obligation of the Jizya tax, came the emancipation from the obligation to fight in the wars of Muslims. This was a trade off nearly any sane individual living during the Medieval period would have taken, gratefully.

Going back to, seemingly, the Rashidun period, leader saw that, given the near-constant state of war the State found itself in, as well as the religious nature of said wars, it would be unfair to compel, or even allow, non-Muslims to die or become orphans and widows as a result of a cause they did not believe in. The de-facto effects of the Jizya tax, however, were often more negative. After the initial golden period of Caliphal power, when armies began to consist almost entirely of Turks, the dhimmi populations ceased benefiting from being excluded from the draft, as Turks were going to be used as soldiers, regardless. Thus, without this benefit, the state of the dhimmi population became one of an unjustly oppressed populations. Works Cited

Cohen, Mark R. Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

0 notes

Text

Potential Grad Thesis

When taken with the context of Islamic Iranian history, Shuja-ud-din Timur’s (presumably) exceptional cruelty and geopolitical might (always, a deadly combination) are, in fact, anything but. Shuja-ud-din Timur and his attributes merely represented the next natural iteration in a trend within the eastern Medieval Middle-East; a trend which has several distinctive characteristics:

Ever increasingly ferocious and vicious conquerors and/or warlords (hereafter, referred to as “military adventurers”) sequentially manifest in the traditionally Persianized regions of the Easter Middle-East.

Each iteration, possessed of an ever-decreasing capacity for mercy and/or compassion.

Each subsequent military adventurer attaining more and more geopolitical clout.

Indeed, this trend is undeniable to even those uninitiated. From the first major military adventurer of the Medieval Iranian landscape, Ya'qūb ibn al-Layth al-Saffār, to the last, Shuja-ud-din Timur, exists a wide gap: one which displays all three of the characteristics of this trend. A reasonable and curious individual might then ask themselves, why does such a trend appear to exist? One from soft-handed rule by military adventurers operating in Iran, to rule characterized by more harshness and cruelty? Herein, we shall attempt to describe and explain this. We shall find that this this trend is not metaphysically teleological, as one might wonder at first glance. Rather, we shall come to an answer using purely materialist theories.

A final note to keep in mind: for the purposes of this post, a military adventurer shall be defined thusly: a male individual, invested with de-facto independent martial power and authority, whom uses it for personal gain (whether taking the form of wealth or prestige), whom is not possessed of any strong royal mandate to rule independently, often leading to the military adventurer placing de-jure power in the hands of a puppet monarch, while hoarding all de-facto power for themselves.

Methodologically, we shall approach this topic through a guiding lens of a pragmatic Marxian Materialist theory of history. Therefore, for the purposes of this post, we shall hold, steadfastly, to the following axioms:

Nothing spiritual or metaphysical in nature acts upon the world in tangible ways. Therefore, no postulations involving such abstract concepts as fate, destiny, or national characters shall be given credence or allowed to factor into our descriptions or explanations.

Human actions and motivations can and are assumed to be ignoble in nature and, ultimately, aimed at the selfish gain of power and/or wealth, relative to their peers.

With these axioms in mind, let us now turn to laying out a description of the aforementioned phenomenon, arcane as it is.

To acquire an understanding of the proposed trend, we should start by examining its beginning. Through the trend we are examining is entirely containing within the post-emergence-of-Islam, we must advance close to two hundred years after the eastern Middle-East was brought into the realm of Islam to find out first major warlord of the Iranian plateau, Ya'qūb ibn al-Layth al-Saffār. Born into a peasant’s life as a coppersmith, Ya'qūb ibn al-Layth al-Saffār, born Rādmān pūr-i Māhak, rose to claim the mantles of Shah of Baluchistan, Shah of Khorasan, and Shah of Sistan. As such, he essentially possessed no mandate to rule. Nonetheless, he was able to expand and consolidate his power and domain, conquering the Tahirids of Khorasan early into his career. Despite his status as a military adventurer, al-Saffar is widely renowned as a just and righteous king, not given to cruelty or discompassion (Bosworth 86).

Ya'qub ibn al-Layth al-Saffar set the bar, so-to-speak, for being taken seriously, for lack of a better phrase, and he set it rather low. Naturally, this is essential for any military adventurer which wishes to have any hope of success. It was set low because he establish a cultural norm in which ethics can fetter the military adventurer without it having necessarily negative consequences on his prestige. Thus, future military adventurers needed not cast off the fetters of morality and, with it, some measure off their humanity. However, were they to go farther, and cast off more of the self-imposed limitations on their actions, they could more easily gain the gravitas and legitimacy any upstart warlord needs to establish themselves geopolitically.

And this is what we can observe with the next major military adventurer: Arp Arslan. The most famous of the Seljuk Turks, Arp Arslan led a great Turkish migration (or invasion, rather) into the Middle-East from its north-eastern border. Arp Arslan, being only nominally Muslim (as many of the pagan-born Seljuk Turks) never abided by Islamic norms, customs, and imperatives regarding warfare and conflict. Though disregarding chivalry lost him the chance to be remembered as a Saladin or an Ali ibn Abu Talib, it did further his goals in life. So fearsome, was he perceived to be, that, when he sent a subordinate tribe related to the Seljuks into Asia Minor, the Basileus in Constantinople called for aid from his Catholic rival, the Holy Father, the Pope, due to the ferocity and efficiency of this new style of war and warlord that Arp Arslan set the standard for.

Genghis Khan was a truly terrible evolution of the eastern Middle-Eastern military adventurer. He razed cities entirely, enabled and/or participated in the rape of thousands of women, and committed cultural genocide, seemingly without a shred of regret. Truly, this was a more dramatic form of the military adventurer model, prior defined by Seljuk rulers like Arp Arslan.

The real zenith of this trend, however, was to come with the emergence of Timur onto the eastern Middle-Eastern landscape. For evidence of this, one only need read to account of one Baravian prisoner being kept by Timur, Schiltberger. Schiltberger writes,

“Then he ordered the women and children to be taken to a plain outside the city, and ordered the children under seven years of age to be placed apart, and ordered his people to ride over these same children. When his counsellors and the mothers of the children saw this, they fell at his feet, and begged that he would not kill them. He would not listen, and ordered that they should be ridden over; but none would be the first to do so. He got angry and rode himself [among them] and said, ‘Now I should like to see who will not ride after me?’ Then they were obliged to ride over the children, and they were all trampled upon. There were seven thousand” (Schiltberger 28).

This account speaks for itself. The horror of Timur’s methods are simply undeniable.

One might now ask, now that we have established the existence of and defined this phenomenon: why did this occur in such a manner? We have already somewhat touched upon the answer: the cultural zeitgeist in which each military adventurer found themselves was such that, in order to make manifest in the minds of both their prospective subjects and their geopolitical peers, they had to top, so-to-speak, their predecessor. In pursuit of this goal, prospective military adventurers, from Arp Aslan to Timur, proved themselves willing to commit any act, no matter how heinous or non-conforming to current (at the time) norms. The author of this post posits that this willingness is a direct consequence of their individual selfishness.

Other explanations could be posited, it bears mentioned. Some, like those involving fate, can be dismissed out of hand. Others, such as those which include national or geographical characters, as in, positing that, in line with Ruth Benedict’s postulations in her book, “The Chrysanthemum and the Sword” (which specifically examines the Japanese national character), the geographical character of the Iranian plateau is such that evermore fearsome and powerful military adventurers are encouraged, are more difficult to dispel. However, in line with our methodology, we shall dismiss it nonetheless.

Ultimately, one is forced to conclude that the described phenomenon is a remarkable point of study. Unfortunately, this is a point which often goes unexamined. Further study of this phenomenon would hopefully:

Further elucidate the psychological progression into cruelty, as acted out by eastern Middle-Eastern military adventurers.

Explain why each iteration of the eastern Middle-Eastern military adventurer was significantly militarily more mighty than the prior.

Discover if, as is the author of this post’s intuition, and to what extent, the military adventurers’ identity as horse-lords (for lack of a better term), contributed to this trend.

Hopefully, more work will be done on this subject in the future.

Works Cited

Bosworth, C. E. "The History of the Saffarids of Sistan and the Maliks of Nimruz." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 59, no. 02 (1996): 380.

Schiltberger, Johannes, and J. Buchan Telfer. "Bondage and Travels of Johann Schiltberger." 2009. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511697593

0 notes

Text

Being Crusaded

The Crusades were a traumatic time for Muslims residing in the Levant. Their homes were looted, their mosques were burned, and their sacred spaces were violated. Any people who experienced such trauma could be expected to change their prior conceptions of the outside group which perpetrated such horrors. However, the manner in which Levantine Muslims changed their views on these outsiders (hereafter, referred to as Franks, despite their multi-ethnic character) is different than one might assume. Indeed, for the most part, their pre-Crusade ideations remained mostly intact, though new ideas emerged to form a new synthesis.

The pre-Crusade Islamic conception of the Franks was one characterized by savagery, untrustability, and stupidity (Hillenbrand 274). But they were also thought to be loyal, tough, and effective fighters. Interestingly, this is somewhat similar to Muslim sentiments toward the Turks. Though one might experience confusion when attempted to reconcile this supposed similarity, it begins to make some measure of sense when one takes into account the traditional philosophical model of the world as being divided into several climes, which determined a peoples’ national character (More or less, these climes correlated, one for each race. For more information, see Hillenbrand. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. ch. 5). In this model, the Turks and Franks inhabited the same clime and, therefore, were possessed of similar national characters. This comparison, present in the medieval Levantine Muslim mind, introduces us to the first revelation of this study: that the Franks were not purely conceived of in negative terms.

Furthermore, the sixth clime in which the Franks resided also bequeathed them other attributes. According to al-Qazwini:

“Its people are Christians, and they have a king possessing courage, great numbers, and power to rule. He has two or three cities on the shore of the sea on this side, in the midst of the lands of Islam, and he protects them from his side. Whenever the Muslims send forces to them to capture them, he sends forces from his side to defend them. His soldiers are of mighty courage and in the hour of combat do not even think of flight, rather preferring death. But you shall see none more filthy than they. They are a people of perfidy and mean character. They do not cleanse or bathe themselves more than once or twice a year, and then in cold water, and they do not wash their garments from the time they put them on until they fall to pieces. They shave their beards, and after shaving they sprout only a revolting stubble. One of them was asked as to the shaving of the beard, and he said, "Hair is a superfluity. You remove it from your private parts, so why should we leave it on our faces?" (Hillenbrand 272).

Indeed, the Levantine view of their Christian neighbors across the sea was one of the prototypical barbarian. However, this was soon to change.

With the arrival of the Crusaders, and their subsequent conquest of the Mediterranean coast, came a new view: one which characterized the Franks as inherently devious, or even diabolical. The taking over of several of Islam’s holiest sites by the Franks did much to stoke the fires of this new ideation. Franks had always been considered unclean, temporally and physically (Hillenbrand 284). The custodianship of Islamic holy sites by Frankish Christian kings was, therefore, unfortunate for Muslims. The idea that the uninitiated could have free access to holy sites, like the Dome of the Rock, drove horror into the heart of many a pious Muslim.

Furthermore, the mere fact that the al-Quds (Jerusalem) could be held by the Dhimmi (Christian, Jews, and sometimes Zoroastrians and Hindus. Litt. “People of the Book”) was an affront to many Muslims’ world-building techniques and, indeed, the Muslim worldview, generally. The Dhimmi were, by definition, wrong in their theological beliefs and, therefore, unworthy of possessing the honor of holding the Holy land in the name of their faith. Once the Islamic mind was forced to grapple with and adjust to these new geopolitical realities, they could no longer merely conceive of the Frank as a witless barbarian. Now the Frank, as well as the Christian, was a rival and equal and, what’s more, right within the Islamic heartland.

The sultans of the Middle-East quickly adjusted, however, to this new reality. The Anatolian ruler, Yaghi Siyan, swiftly exiled the Christians from the lands under his control (Maalouf 19). We should note here, though it is somewhat auxiliary to our purposes, that the exile only applied to adult Christian men. This was the natural consequence of the idea, not at all unique to Muslims, that women and children were not fully people and, therefore not subject to the rights or responsibilities of full male citizens.

Other rulers, such as the young Seljuk sultan, Kilij Arslan, began to tap into rhetoric ahead of their time. Arslan began attempts to strengthen pan-Turkic identity, calling on all Turks to come together to resist the Frank (Maalouf 14). In prior times, Turkic tribes were endlessly locked in inter-tribal conflict. This state affairs can be most easily observed by examining the so-called “Anarchy at Samarra”, which occurred a mere two centuries before the Crusades. By and large, the was no love lost between Turkic tribes. That the circumstances warranted a call for Turk fraternity, and in a medieval setting no less, demonstrates the new respect Turks, and Muslims generally, were beginning to have for the Franks and Christians.

Old stereotypes persisted, nonetheless, however. Writing after the First Crusade had found success in the Levant, Usama b. Munqidh portrays the Franks using “stereotyped phrases of contempt” (Hillenbrand 260). Thus, the new attitudes of Muslims towards the Christian Franks did not supplant the prior Islamic biases but, rather, merely complemented them.

Ultimately, the Crusades did lead to a marked shift in Islamic sentiments toward their Christian and Frankish neighbors. Though, in some ways, the Franks’ image was slandered, as in the case of their immorality in presuming to rule the Holy land when they had no right to do so, in other ways, such as in the higher level of respect granted to them, the Franks’ image improved, from a certain point of view. Overall, one must conclude that the Crusades effect on the Muslim psyche, as it relates to the Franks, was surprisingly mild and even complementary to their prior conceptions.

Works Cited

1. Hillenbrand, Carole. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012.

2. Maalouf, Amin. The Crusades through Arab Eyes. New York: Schocken Books, 1985.

0 notes

Text

The Emergence of the (Religious) Shia

Continuing on from the prior post about early Islamic historiography, before we can even begin to touch upon the actual subject of this post (the Shia), we must next consider how the modern Islamicist scholar may discern the accuracy (approximately) of an early Islamic historical compilation. As Donner states, and as we have seen, merely accepting at face value the word of the Muslim sources is fraught with issues (Donner 46-47). Donner instructs one to pay attention to the author’s “strategy of compilation” (Donner 47). That is to say, there is an imperative to closely scrutinize the author’s selection of texts he chose to include, how they are placed within the texts, how and when sections repeat, and whether any manipulation or altering seems to have occurred. Though the corpus of work in this area is vast, applying, rigorously, this sort of methodological approach is certain to assist on in discerning some measure of the historical, objective truth. Though we shall not be diving into the primary sources on the development of the Shia in enough depth to make much use of this methodological approach, it is, nonetheless, essential to keep this methodology in mind when delving further into Islamic history.

Having put an end to the topic of historiography for the moment (doubless, it is be picked up again, so-to-speak, in later posts), let us now address an equally important topic: how the Sunni-Shia divide transformed from a political distinction to a religious, sectarian one. Though one may be tempted to assign sectarian staus to the arlist partisans of the Prophet’s son-in-law, Ali, ibn Abu Talib, this is a position prone to folly. During the Rashidun period, so the mainstream Sunni narrative states, the Muslim community was still of one mind, so to speak, at least in the religious sense. Indeed, until the proto-Shia community came under the influence of the 6th Imam in the Twelver tradition, the Shia, as one knows them in the modern age, had not yet emerged. On that not, let us now turn to those most internally controversial of Muslim sects: the Shia.

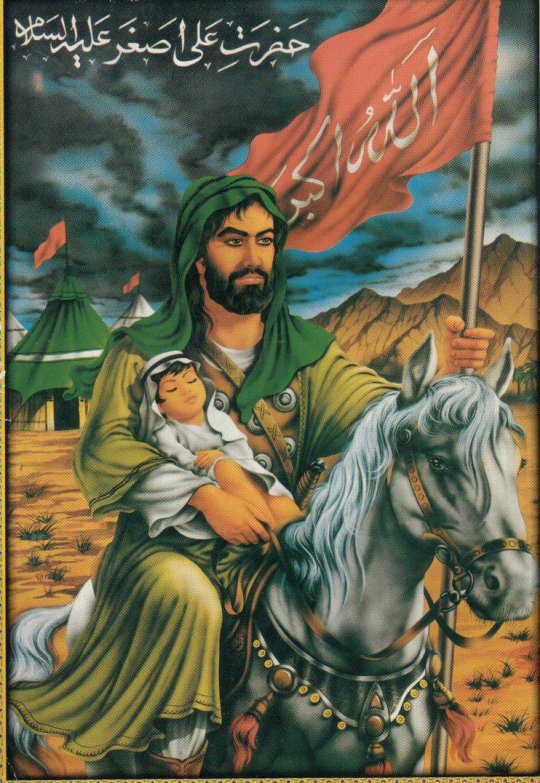

What is often surprising to the layman about the early Shia is that they, in many ways, bear little resemblance to their modern counterparts. The difference is most striking when comparing them to those Shia most well-known to the West and on the international stage: the Twelvers of Iran. Indeed, the early Shi’ites were, merely, a political faction in support of the Alids (the descendants of Ali) and not a realized ideo-religious sect. Naturally, the question then presents itself: how did this change in nature arise? In pursuit of an answer to this question, we must turn our attention to the early medieval period of Islamic history, and, especially, to the 6th Shia Imam, Jafar al-Sadiq.

It was during the “reign” of Jafar al-Sadiq that some of the most recognizable Shia traditions began to crystallize. Many of these traditions were, interestingly, evolutions of the practices of the Pre-Islamic Bedouin tribes. For example, during this time, the old Bedouin tradition of raja, the idea that a hero might rise from the dead, was adopted by many despairing Shi’ites hoping for the return of Ibn al-Hanafiya or, even better, the return of Ali ibn Abu Talib, himself (Hodgson 6). Naturally, this bears a striking similarity to the later Twelver conception of the return of the Mahdi. Further, divination and prophecy, characteristic of Pre-Islamic Arabia generally, began to reassert itself amongst the partisans of Ali (Hodgson 6). Though at first confusing, given the generally held modern view of the Prophet Muhammad’s sentiments towards future individuals holding supernatural abilities (that there will not exist any more such individuals), Hodgson illuminates, within the early Ummah, this later interpretation of Muhammad’s statement about the Prophet being the ‘seal of the prophets’ was far from solidified, stating “ After all, there is nothing very explicit in the Qur'an, apart from the ambiguous phrase about Muhammad's being the 'seal' of the prophets, to debar even major prophets from appearing after him; to say nothing of God's speaking through minor figures to confirm the faith given as had admittedly happened among the Jews” (Hodgson 6).

This reemergence of the old tribal Arab ways which began to assert itself more prominently during the time of the 6th Imam doesn't, at first glance, seem to have anything at all to do with Jafar al-Sadiq, himself. However, it is my assertion that Jafar al-Sadiq's withdrawal from the contest for temporal power over the Dar al-Islam (roughly, the lands where Muslims are dominant) allowed for a certain degree of spiritual and intellectual autonomy. Without a source of legitimate condemnation of certain quasi-heretical beliefs, the Shi’ites turned to the seductive pagan beliefs of the old ways, which could grant them some solace during such turbulent times for them. Thus, had the 6th Imam somehow seized the Caliphate and chosen to assert both secular and religious authority, such innovations would likely have never emerged.

Also, it must be mentioned, other, less dramatic, distinctions also arose during this time. An example of this type of innovation is to be found within the de-tabooification of speculation on the appearance of God, particularly, his face (Hodgson 7). Mainstream non-Shia Islam had always discouraged this kind of philosophical speculation.

Finally, we must address the man, himself: the Iman, Jafar al-Sadiq. The most obvious way the 6th Imam contributed to the establishment of the Shia as a sect, separate from the mainstream Islam being spread in the conquered territories, was in making the distinction between spiritual and temporal leadership within the Shia community. In making the transition (interestingly, of his own accord), from the presumptive secular ruler of the Shi’ites to the purely spiritual leader of the devotees of Imam Ali, Imam Jafar laid the foundation for a new direction for the Shia community: one characterized by and emphasizing the religious devotion towards his lineage. As if to drive home this new direction, Imam Jafar, after the ascension of the proto-Sunni Abbasid dynasty to the mantle of the Caliphate, made the journey to the Abbasid court, likely to pay homage or even tribute (Halm 22).

Ultimately, the emergence of the Shia as a distinct religious sect was a complicated and multi-faceted phenomenon. It resists, therefore, many rigid methodological approaches. The Diffusionist approach works, but only somewhat. Given the influences of the pre-Islamic Arabs on Shi’ism, the chief Diffusionist postulation, that the main way new traditions and innovations arise is through the appropriation of certain practices and ideas, intact, from outside, does apply. However, given the independent actions of the 6th Imam, predicated on the geopolitical realities of his time, the Diffusionist model is necessarily deficient. The Post-Structuralist model, furthermore, is also flawed in this context. The Post-Structuralist axiom that material pressures are the dominant motivations for historical events, cannot hold strictly true around this topic, as there are far more pressing historiographical concerns within Shi’ite history, this approach is simply unhelpful. In conclusion, the Shia, and their metamorphism into their modern form is extremely multi-faceted and interestingly complex. Thus, we must, as so often occurs within Islamicist studies, not allow ourselves to be too concerned with the Sunni narrative, especially if it comes at the expense of the Shi’ite narrative.

Works Cited

1. Donner, Fred M. Ibn ʻAsākir and Early Islamic History. Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 2001.

2. Hodgson, Marshall G. S. "How Did the Early Shîa Become Sectarian?” Journal of the American Oriental Society 75, no. 1 (1955): 1. doi:10.2307/595031

3. Halm, Heinz, and Allison Brown. Shia Islam: From Religion to Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 1999.

0 notes

Text

Muhammad and Early Islam

224–651 CE The Prophet, Muhammad and his thoughts (or at least what have been considered to be his thoughts), as is importantly distinguished from the Qur’an by its tradition appraisal as the divine word of God alone, are obviously massively important to Muslims in the Middle-East. The potential reasons and explanations for this are somewhat self-evident, given his importance in the dominant religion of the area. However, it is important to mention that these areas are outside of the purview of this post. Rather, we shall take the cultural importance of this as a given and, instead, turn our focus onto the ways in which Medieval Muslims brought their value of Muhammad’s era to bear when engaging in the creation of historical works.

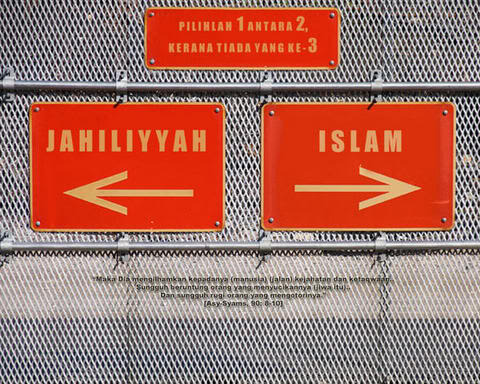

One must begin with what we factually know to be true of the historical period our subjects chose to concern themselves with. Here, However, we encounter a problem: that there is a near complete lack of historical records and, therefore, objective certainty about said period (Sizgorich 13). This, the modern historian must simply accept. Once, accepted, they shall then concern themselves with merely noting and cataloging the varied ways in which believers have treated the Jahiliyya (time of ignorance in Arabic, denoting the pre-Islamic period of Arabia), the reign of Muhammed, and the Rashidun (rightly-guided in Arabic, denoting the period immediately succeeding the death of the prophet Muhammad) periods... at least at first.

Muslims have often approached with derision the Hijazi pre-Islamic period and culture, traditionally associated with and identified as the Jahiliyya. Indeed, even the root from which the term is derived, jahala (meaning, roughly, to be barbaric or engage in barbarism in Arabic), implies a sort of inherent inferiority to the post-Muhammad age (Tajddin). Part of their hostility toward this time is, perhaps, understandably, a result of their hesitation to implicitly legitimize a way of life, the rejection of which was a foundational aspect of their self-conception. Though this negative conception was likely less present in the Rashidun period, certainly by the time we observe the emergence of sources in any real volume (that is to say, in the early reign of the Abbasids), this attitude was thoroughly entrenched. For example, as Rina Drory, a well-respected scholar of Medieval Muslim and Jewish history, states about the state of poetry (an indisputable staple of Arab culture in the pre-Islamic period) in the cultural landscape during the reign of the Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur, “...official Islam impugned poetry in general, as well as anything that smacked of pre-Islamic values..." (Drory 34).

It must be noted, however, that this view, while seemingly dominant in the era from which the earliest copies of sources survive, was not the only one held by the early Islamic community. Sizgorich identifies two primary and foundational sentiments present in the early Islamic era: the “Pious” and the “Tribal” (Sizgorich 22). The aforementioned sentiment, common to the cities and governments, is an example of the “Pious” sentiment, characterized by a mental and symbolic vocabulary of individualistic and character-focused conceptions. The alternative view, the “Tribal”, as Sizgorich calls it, glorifies the Arabs as a people and the varied Arab tribes which made it up. This sentiment was, presumably, more common among nomads, country-dwellers, and, perhaps within the Arabian peninsula itself. The presence of this “Tribal” view, therefore, is prominent enough to warrant a mention, for the sake of fairness, if nothing else.

The period corresponding to the life and reign over the Arabian peninsula of the Prophet Muhammad is similarly shrouded by the base psychological want to decisively settle upon culturally convenient convictions concerning the foundational historo-mythological pillars of one’s society or civilization. In this case, Islamic historiography has, it seems, tended to impose the values of the society at the time, as well as the individual(s). Often, this has meant directly fabricating, or at least exaggerating, Muhammad’s “virtue”, as subjectively defined by the writer.

For evidence of this, one need only turn to the popular (but likely untrue) hadith, as recorded by Abu Dawud, compiler of the third “canonical” Sunni hadith collection, stating that the Prophet Muhammad’s said, “Allah shall send for this Ummah at the head of every hundred years a Mujaddid (Abu Dawud, Hadith 4278). A “Mujaddid” (from the Arabic root, tajdid, meaning “renewal”) is a Sunni term referring to those prophesized to come and “cleanse” the religion of God of any heretical or Pagan influences which may have crept in. The concept bears a deathly similarity to the role of the prophets in the Islamic tradition and, therefore, this hadith is unlikely to be true because it violates the spirit of a statement in the Qur’an (itself, an older and more legitimate source), which states that the Propet Muhammad is the last prophet of God. One might suggest that God might still send, in accordance with the Islamic tradition, individuals which bear many of the aspects and traits of a prophet, such as their prophecied arrival or their role of purifier of the Lord’s religion, but to assert this would be to devalue the meaning of word and concept “Prophet” down to the level of being a mere title. Therefore, one may take this hadith to be false and evidence of the values of a Persian religious foundation creeping into the accounts of the Prophet Muhammad and his reign (perhaps unsurprisingly, as Abu Dawud was a scholar of Persian origin).

As this is an assertion which severely requires explanation, let us next examine exactly how the religious axioms of the Persian civilization seem to be present here. Firstly, popular Zoroastrian folk tradition asserts similar sentiments about future “purifiers”. Examples abound, from the Shah Bahram legends to the Saoshyant prophecy. The Shah Bahram, according to tradition shall be a resurgent king who shall revivify and purify Iran and Zoroastrianism of the dragon that is foreign influences, oppression, and unvirtuousness (Tavadia 29-36). Similarly, the prophesized Saoshyant (the Zoroastrian equivalent of the Jewish Messiah and the Muslim Mahdi) will come, according to tradition, to restore the faith to its former glory and, in so doing, save the world (Wallis 18). Furthermore, there will be multiple “Saoshyants”, as written in the Ard Yasht Avesta (Yast Avesta, verse 17.1).

Given these Persian conceptions, one may cast doubt onto Abu Dawud's historiographic methodology concerned the Prophet Muhammed, since the likelihood of him being completely unbiased by his geographic and cultural environment seems to be slim. Clearly, it is fair to assert that Abu Dawud’s Persian at least subconscious theological psychological background, at the very least, clouded his methodology when compiling his hadith collection. A similar case may be made for a vast number of Muslim historical sources.

Before continuing, it should also be noted that non-Islamic sources often also fall into this error. As Cook states of an Armenian late-antiquity source on the Prophet Muhammad and Islam, the Armenian source asserts, “Muhammad told the Arabs that, as descendants of Abraham through Ishmael, they too had a claim to the land which God had promised to the seed of Abraham.” (Cook 76). Muhammad may indeed have thought this but this statement is not to be found in the Qur’an, nor in any of the earliest Muslim sources. Given this, one should assume that the Armenian source was simply ascribing his own understanding of religion onto Muhammad’s motivations. Therefore, in the interest of fairness, let one not conceive of the Muslim scholars as particularly biased.

At other times, the want to assign features to the Prophet Muhammad which are culturally convenient has meant ascribing to Muhammed an openness to outside, non-Semitic cultures. One can observe this when examing the hadith detailing the Prophet’s dictation of letters to both the Christian Eastern Roman Empire’s Basileus, Basil, and the Zoroastrian Sassanian Shahanshah, Yazdgird, informing them of a new revelation from God and emploring them to convert to Islam. It goes without saying that this certainly did not occur. Muhammed would’ve surely, to mention one problem with ascribing any sort of truth to this hadith, have likely been far too busy with the administration of a state and the leadership of a large ethno-religious community to engage in what would’ve been an obviously fruitless and meaningless endeavour, such as is purported.

One might object(and many do) that the Prophet Muhammad truly believed it was his duty to inform and implore all to embrace his new religion and submit to God’s will, regardless of the political clime. There exists a problem with this objection, however, which is that such a grievance arises from an exceptionally gracious historiographical perspective: one which is now uncommon to academic historians and, generally discouraged. Indeed, the Marxist and Post-Modernist historiographical methods have become increasingly popular in recent years and are infamous for their particularly harsh presuppositions about historical figures (Sullivan).

Moreover, some traditions began, in the aftermath of the consolidation of the Islamic Empire, that Muhammad had been the subject of scrutiny and, subsequently, verification by an ascetic Christian monk (Sizgorich 11). As Sizgorich states,

“In asserting the authenticity of Muhammad's revelation, for example, several early Muslim narratives depict the Prophet as being recognized first by Christian monks. In so doing, these narratives deploy a figure - the monk - which had been recognized and acknowledged for more than four centuries in communities of variant confessional alignment as a discerner of truth and godliness to support truth claims crucial to early Muslim programmes of communal self-fashioning” (Sizgorich 11).

Clearly, the cultural convenience of such a story precludes it from having any sort of basis in objective fact. The point to take away is, to be blunt, that the traditional Muslim sources’ assertions about the events which occurred in 7th-century Arabia are to be considered mostly untrustworthy.

A further example that illustrates the difficulty in attempting to discern any modicum of objective truth from the early Islamic narrative is to be found in, by far, the most contentious time period for Medieval Muslims: the Rashidun Era, as it is known to Sunnis. It would be uncontroversial to assert that major source of disunity in the narrative accounts of this period is the major sectarian divide in the Islamic faith: the Sunni-Shia divide. The early Islamic narrative is quite often the subject of this agent of sectarian distortion. Examples abound of this phenomenon. One concerns the reaction of Ali to his failure to succeed to the leadership role in the Ummah to the 3rd Caliph, Uthman. Sunni historical accounts describe Ali as humble and completely fine with Uthman’s succession, immediately pledging an oath of his loyalty to him. It is interesting to note here, that, as is perhaps surprising to those uninitiated in Sunni Islamic thought, the Sunni historical sources also hold Ali in high esteem and, generally, approve of his eventual ascension. Shia sources, in contrast, hold that Ali only begrudgingly pledged loyalty to Uthman. Virtually all aspects of the early Islamic narrative are affected similarly.

Given all of the aforementioned issues facing the modern Islamicist historian, a question presents itself: what methodological approach should one take when attempting to address this issue? One approach, as put forward by Dr. Aaron Hagler is to approach the topic through the unconventional lens of theater. Hagler proposes that the modern Islamicist treat the varied sources and historians as “actors” essentially (Hagler 4). Though theatre may initially conjure within one’s mind the image of a performance meant chiefly to entertain. However, as Hagler states, various authors have conceived of their work as, chiefly, a way to, “ argue, persuade, teach, and communicate information” (Hagler 5). Given this interpretation, the Islamicist can grant some measure of scholarly legitimacy while simultaneously providing a framework upon which to lay all of the reservations which one shall have towards them, given the aforementioned issues. Furthermore, this method has the advantage of allowing easily for the accounting of the author’s intentions concerning his audience (Hagler 12). This is an especially important component of historiography within the Islamic context, it should be noted.

Ultimately, there are obviously many factors which make the study of the early Islamic period difficult and problematic. However, it is important to not judge the sources or scholars of the period terribly harshly. After all, it was never their intention to complexify the work of Western scholars over a millennium in the future removed. There are even reasons for hope, as new methodological approaches are attempting to lay out potentially better and clearer ways of engaging in interpretation. In conclusion, we must simply attempt to do the best we can with what we have. We should not wax discouraged because of the extent of work and care which must be taken with regards to Medieval Muslim sources.

Works Cited

1. Sizgorich, Thomas. “Narrative and Community in Islamic Late Antiquity”. Past & Present, No. 185, pp. 9-42. (2004).

2. Tajddin, Mumtaz Ali. "Jahilliya." Ismaili.net. Accessed September 18, 2018. http://ismaili.net/heritage/node/10495

3. Drory, Rina. "The Abbasid Construction of the Jahiliyya: Cultural Authority in the Making." Studia Islamica, no. 83 (1996).

4. Abu Dawud, Hafiz. Sunan Abu Dawood. (~850 CE).

5. Tavadia, J. C. "A Rhymed Ballad in Pahlavi." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 87, no. 1-2: 29-36. (1955).

6. Wallis, Wilson. Messiahs: Christian and Pagan. Hardpress Publishing, (2012).

7. Ard Yasht Avesta. (~200–600 CE).

8. Cook, Micheal. Muhammad. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

9. Sullivan, Nate. "Post-Modernism & Historiography in the 20th Century." Study.com. Accessed September 19, 2018. https://study.com/academy/lesson/post-modernism-historiography-in-the-20th-century.html.

10. Hagler, Aaron. "The Shapers of Memory: The Theatrics of Islamic Historiography." Mathalno, 5, no. 1 (2018).

0 notes