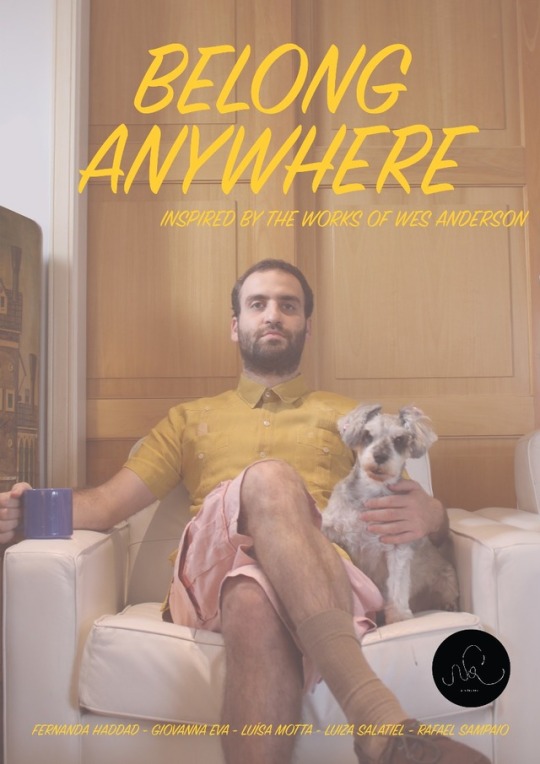

Registro do Processo Criativo do trabalho de conclusão da disciplina Semiótica Aplicada, realizado pelos alunos Fernanda Haddad, Giovanna Eva, Luísa Motta, Luiza Salatiel e Rafael Sampaio. Turma PP3E, ESPM-2018/1.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Auto Avaliações

RAFAEL SAMPAIO

8/10

Acredito que consegui contribuir ativamente para o desenvolvimento dos trabalhos dessa disciplina, dando sempre meu melhor nos momentos que participei e conseguindo entender os conceitos trabalhados. Meu desempenho só foi um pouco afetado pela falta de organização, que fez com que o tempo fosse mais curto e as atividades precisassem ser realizadas sob pressa e pressão.

LUIZA SALATIEL

8/10

Durante a realização de todo o trabalho, busquei estar sempre disponível pro meu grupo e solicita a ajudar. Com isso estive presente desde a criação da produtora, gravação do curta e auxiliando na montagem da apresentação.

GIOVANNA EVA

8,5/10

Creio que produzi ideias e contribui com o andamento do trabalho da melhor maneira. Desde a montagem da apresentação até o desenvolvimento do roteiro. Apesar do tempo, que poderia ter sido mais bem aproveitado, acredito que a minha participação contribuiu diretamente com a qualidade do trabalho.

LUISA MOTTA

7/10

Contribui com ideias e na execução do trabalho. No entanto, meus horários de trabalho não batiam com os dos demais membros do grupo. E de última hora, mudamos a data do dia de filmagem para um dia em que eu trabalhava. Assim, não pude contribuir o quanto eu queria para a produção final.

FERNANDA HADDAD

9/10

Contribui para o grupo da melhor forma que pude, no desenvolvimento do site, criação de postagens e na ideia para o curta, apenas não consegui comparecer no dia da filmagem porque os horários não batiam, mas fiquei responsável pela parte de edição.

AVALIAÇÃO DO GRUPO

9/10

O grupo trabalhou bem sem longos problemas ao longo do semestre, quase sempre foi possível dividir as tarefas de maneira equilibrada, sem grandes problemas de sobrecarga. Sempre conseguimos chegar a conclusões conjuntas e desenvolver o trabalho em grupo.

0 notes

Text

CENAS ESCOLHIDAS PARA ANÁLISE

youtube

No trecho acima, além de Richie e Royal, um terceiro elemento entra em cena, sendo esse a ave da família Tenenbaums a qual Richie teria libertado anos antes. Nomeado Mordecai, o pássaro retorna a ele, não coincidentemente, no mesmo momento em que Richie é sincero com seu pai a respeito de seus sentimentos por Margot. A volta de Mordecai representa a conquista de Richie por finalmente ter conseguido expressar o amor romântico que sente pela sua irmã.

Na cena seguinte, Mordecai repousa ao lado do casal quase como se fosse um aliado, representando a transparência emocional de Richie, que agora, depois de anos, volta a pertencê-lo.

1 note

·

View note

Text

CENAS ESCOLHIDAS PARA ANÁLISE

youtube

Na cena acima, o personagem Richie entra no banheiro após descobrir da vida de Margot com o atual marido, para em frente ao espelho e começa a raspar os seus pelos do rosto e da cabeça, e após uma pausa, diz que vai se matar no dia seguinte, porém depois de instantes, pega a lâmina e corta os pulsos na vertical. Essa é uma cena do filme na qual há um momento de mudança, não só no rumo da narrativa, mas também na forma como a edição é feita. Os ângulos, a ambientação, a tonalidade anestésica que compõem a cena marcam a singularidade desse momento.

Quando Richie comete suicídio, seguido de flashbacks de sua infância e da imagem de Margot, fica clara a influência dela naquele acontecimento. A mudança de sua aparência visual, a retirada de todos os elementos que o caracterizavam desde o início do filme representam uma ruptura, não só com suas características estéticas, mas principalmente com o desejo cultivado desde a infância, de no futuro poder viver um romance com Margot, sua irmã adotiva. Esse desejo é de certa forma descartado quando o personagem descobre que sua irmã está casada, e portanto o que ele tanto sonhou durante anos não se realizaria, isso é evidenciado durante o seu processo de mudança de aparência. Porém, mesmo dando a impressão de que Richie realmente esteva disposto a seguir a vida como o seu novo eu, essa sua nova versão não via sentido em viver uma vida sem objetivos, desejos, enfim, uma vida sem Margot. Então quanto a isso, a única solução que ele encontrou foi na lâmina de barbear, que de repente, assim como ele próprio, para de fazer sentindo exercendo a sua função comum (que no caso seria barbear) e todo o seu sentido se molda em torno de uma função um tanto quanto óbvia porém inimaginável, a de instrumento mortal.

0 notes

Text

COME TOGETHER - COMERCIAL H&M

O curta feito para a marca de roupas H&M, conhecida mundialmente teve como temática o natal e o ano novo em um trem, na ótica de Wes Anderson. A preferência pela simetria, por personagens com aparências diferenciadas e o movimento da câmera, são características que levam o espectador a acreditar que está prestes a assistir um filme do diretor. De maneira sutil mas interessante, os personagens passam pelo corredor do trem peculiar com roupas da marca. É a mescla perfeita entre a estética de Wes e a demanda da marca nessa época do ano em países mais frios.

youtube

0 notes

Text

FILMES A SEREM TRABALHADOS

Os Excêntricos Tenenbaums.

Stella Artois - Comercial

0 notes

Text

REFERÊNCIAS

Crítica Rushmore

Rushmore is the best film Wes Anderson has ever made, and it would take something incredibly special for him to top it. Not because the filmmaker has less talent now than he did 15 years ago, but because the Anderson that made Rushmore has, more or less, disappeared.

The movie tells the story of ambitious, eccentric, insecure 15-year-old Max Fisher, a kid at a prep school who spends way too much time on extra-curricular activities, not enough time on his studies and is always trying to make his mark on his beloved Rushmore Academy.

Right from the start of Rushmore I still get that jolt that I’m watching something special. It’s such an original, efficient, beautiful, sad, hilarious work. Anderson is completely confident in his ability not just with his eyes, but also with his heart.

Before I talk about that film, though, it’s important to look at the film in the context of Anderson’s career. As it stands now his fans unofficially divide his films into two categories: The first consists of his first three films (Bottle Rocket, Rushmore and The Royal Tenenbaums). The second includes everything he’s made since. His first three films can easily be described as his most universally loved while his later efforts like The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou and Moonrise Kingdom are met with a more mixed reaction. That’s not to say that they don’t have their defenders, but the number of them is much smaller. I still attest that The Darjeeling Limited and Fantastic Mr. Fox rival his best work, but I do concede that there’s still some magical, unexplainable element missing. Some have argued that Anderson’s films post-Tenenbaum lack a powerful emotional element, but I don’t buy that. Instead I think the emotions are there, but they are somewhat sacrificed to what has become a slightly bloated visual style.

Anderson’s films have these very easily noticeable qualities: a distinctive, detail-focused visual style and an equally discernible comedic dryness and emotional subtlety. You know a Wes Anderson movie from the first frame. That’s what makes him so special and that’s why even his lesser efforts are still pretty great.

His later films have a larger scope and budget that gave him the freedom to experiment, but that freedom also causes him to lose focus on his characters. The LIfe Aquatic is a funhouse of visual gags and really bonkers characters (especially Willem Dafoe’s Klaus), which makes it very entertaining. But the film’s core emotional story between Zissou (Bill Murray) and his possible son (Owen Wilson) doesn’t have the emotional pull it should. By the end we’re supposed to feel for this relationship, but the film becomes so muddied in its own gleeful imagery and imagination that we don’t. Moonrise Kingdom falls prey to the same problem. For me, The Darjeeling Limited and Fantastic Mr. Fox find Anderson moving back in the right direction, and the more I watch Fox the better it gets, but, for me, they don’t reach the height of his early career trifecta.

There’s no denying that for the first part of his career he found a beautiful balance with his unique visual and emotional styles. You can see as he evolved with Bottle Rocket, Rushmore and Tenenbaums his visual style slowly took a larger and larger place in his films.Bottle Rocket’s minimal budget (it’s claimed to be $7 million, but I just don’t believe it) made him disciplined visually. We still have the yellow jumpsuits and the great fireworks montage, but the film feels beautifully minimalist and Anderson leans heavily on his great comedic instincts (“Is that tape on your nose?” “Exactly.”), deft emotional touches and unique characters to make the film so memorable.

Two films later with The Royal Tenenbaums, Anderson had a much larger budget ($21 million) and an ensemble cast that included the likes of Gene Hackman, Anjelica Huston, Gwyneth Paltrow and Ben Stiller. There’s absolutely nothing minimalist about this movie. It’s big and bold, but it still maintains the strong emotional resonance of his early works. When Stiller’s Chas, an energetic ball of rage, finally concedes his love for his father it’s a beautiful moment because we care so much. The film’s third act is littered with one emotional payoff after another. It’s one of Anderson’s true masterpieces, but it is now obvious, looking at its ambitious visual sense, this was the film that began Anderson’s move into, for lack of a better phrase, style over substance.

In between Bottle Rocket and Tenenbaums, though, Anderson made Rushmore, a film that announced to the world that he was indeed a first-rate filmmaker. It’s also remains the pinnacle of his already decorated career.

The two main characters in Rushmore are Max Fisher (Jason Schwartzman) and Herman Blume (Bill Murray). While one is a teenager at a prep school and the other a 50-something, self-made millionaire the two men share many of the same qualities. For starters they’re both secretly lonely and inherently immature. So, of course, they instantly form a friendship.

It’s only fitting that they both fall for the same woman, Rosemary Cross, a first-grade teacher at Rushmore. It’s obvious she’s too old for Max and too mature for Herman, but the two men fight for her love even if it costs them their newfound friendship.

Just going over the bare bones of the film’s plot reveals that it’s a screwball comedy underlined with sadness. This is perfect for Anderson, who always seems to sneakily go for big laughs. And Murray’s brilliant delivery only makes things easier. Like when he stares sadly at his wrestling twin boys and admits, “Never in my wildest dreams did I ever think I’d have sons like these.” Anderson also uses Murray in brilliant and simple physical bits like his embarrassing attempt to spy on Rosemary by hiding behind a tree, getting caught and then trying to play it cool. And Schwartzman just kills it as Max in all his insecure and arrogant glory. He makes the now infamous exchange of “These are O.R. Scrubs.” “Oh, are they?” one of the film’s centerpieces. Rushmore is laced throughout with jokey comedic moments like these and they work because Anderson, and co-writer Owen Wilson, are just being genuine to their characters. If you make childish characters you should have them doing childish things. In fact the war of pranks that comes out of Max and Blume’s rivalry over Rosemary, which includes Blume driving over Max’s bike and Max getting him back by putting bees in the man’s hotel room, could be in a comedy for kids. This film is so zany when you think about it that it’s amazing how emotional things get.

As much as the comedy in the film is great, and RUSHMORE is, first and foremost, a comedy, it’s the meticulous and subtle scenes of pathos that make this Anderson’s true masterwork.

If you watch Rushmore closely you understand that a line of dialogue, a look, a shift of a hand can tell you everything about what’s going on inside a character. The film is filled with so many important small moments that when it’s over it feels like you’ve gone through a journey that could not have been squeezed into a breezy 93 minutes.

In fact the main emotional conflict in the film, Max dealing with the death of his mother, is only mentioned about a handful of times. But it’s the key to who Max is. He’s a busybody because he doesn’t want to spend time at home missing his mother. He’s dismissive of his father sometimes because that’s the only link he still has to her. He loves Rushmore because it was his mother’s idea he go there. Anderson never dwells on any of this, but instead allows Max’s actions to reflect these feelings.

And the visual style of Anderson is apparent throughout, but never feels overdone. There’s the breathtaking, French New Wave-inspired montage of Max’s numerous after-school groups and clubs (my personal favorite being “The Bombardment Society”). Also Murray’s The Graduate-esque cannonball-turned-underwater-solace scene comes to mind as well as the continuing theater curtain that covers the screen whenever the film story moves to a new month.

By the end, the world that Anderson creates and the characters than inhabit it come to a massively satisfying conclusion as Max premieres his latest Vietnam-set play. It’s a beautiful collage of images and music and emotions that comes to a head when Max asks Rosemary, whom both he and Herman fail in wooing, to dance. He asks the DJ to play a certain song. We hear The Faces’ “Ooh La La” and are treated to one of Anderson’s signature slow-motion closing shots that he’s used throughout his entire career.

In general terms Rushmore is Anderson’s greatest achievement because it’s his perfect balance of style and substance. His visual eccentricity doesn’t overshadow his characters and the emotional resonance of the film and, in fact, accentuates it beautifully.

After his first three films the potential of what a Wes Anderson movie can be has been brought down by his need to make his film’s visual sensibility overshadow its story and characters, especially with The Life Aquatic and Moonrise Kingdom. They are all still pretty fantastic and some get close to finding that magic, but until he can strike that balance of style and substance that make his first three films, and Rushmore in particular, so loved, we’ll just have to keep revisiting his masterpiece.

http://birthmoviesdeath.com/2013/09/16/rushmore-and-the-style-and-substance-of-wes-anderson

comentários

Como uma das primeiras obras de Wes Anderson, Rushmore tem algumas características que merecem ser destacadas. Max Fischer, o principal personagem do filme, é um personagem com diversas peculiaridades e detalhes que são desenvolvidas e vem ao público ao longo do filme. Sua relação incomum com os outros personagens também têm muito a dizer, principalmente quando se refere à Herman e Rosemary. Em todas as cenas em que as personagens interagem, o diretor consegue trazer mensagens e diálogos repletos de significado. Ao mesmo tempo, o filme também não deixa a desejar no âmbito visual, que é hoje um dos principais focos do artista. Esse equilíbrio entre visual e significado pode ser considerada a grande virtude do filme, que foi produzido no início da carreira de Wes, enquanto seus orçamentos eram menores e a necessidade era fazer menos com mais.

Crítica O Grande Hotel Budapeste

The cinema of Wes Anderson is nothing if not mechanical. Watching his movies is less like marvelling at the silent workings of a Swiss watch than goggling at the innards of a grandfather clock, cogs and pulleys proudly displayed. Theatrical framing devices are everywhere, from book bindings to doll's houses to miniature stages and fluctuating screen ratios, with chapter headings a recurrent feature. As for the performances, one imagines that if Anderson were ever to include a "gag reel" of outtakes from his movies, it would include shots of an actor raising an eyebrow a millimetre too high, or placing a teacup an inch to the left of its allotted space upon a table.

Such choreographed precision and overwrought artifice can make Anderson's movies seem emotionally sterile – the all-too-arch constructions of a "smart cinema" icon whose idea of casual dress is (non?)-ironic corduroy. Yet rigorous physicality is also the key to screen comedy, following a tradition that dates back to the silent era and the carefully constructed pratfalls of Chaplin and Keaton. Significant, then, that The Grand Budapest Hotel is both Anderson's most tightly wound and funniest film in years, lacking the melancholy charm of The Royal Tenenbaums or Moonrise Kingdom perhaps, but more than making up for it in terms of elegantly capering contrivance.

The action centres upon the titular establishment, a once-grand confection of a building located in the imaginary European state of Zubrowka, lurking somewhere between the Best Exotic Marigold and the Overlook hotels, with Anderson's prowling, panning cameras occasionally resembling a cartoon caricature of Kubrick on speed. As ever, the story unfolds as a series of boxes within boxes. Our first narrator, a writer (variously played by Tom Wilkinson and Jude Law) hands the baton to a second storyteller, Mr Moustafa (F Murray Abraham, embodied in younger years by Tony Revolori) who in turn draws our attention to the real heart of the matter: the charismatic concierge, M Gustave (a splendidly rancid and randy Ralph Fiennes). Back in the 30s, Gustave was the hotel's primary attraction, a vision of purple-clad slickness attending the guests with oily efficiency, bedding the dowagers whose patronage was his fetish. When one such dowager (an unrecognisable Tilda Swinton) expires, leaving Gustave a priceless painting, the family revolts, and a frenetic caper is set in motion involving art theft, murder, love, prison breaks, steam trains, cable cars, occupying armies (non-specific war breaks out), dead cats, a clandestine order of fraternal concierges and elaborate cakes. In boxes.

With Lubitsch and Hitchcock his guiding lights, and author Stefan Zweig providing inspiration for a screenplay co-written with Hugo Guinness, Anderson conjures a fictional vision of Europe that nods its head towards the Hollywood backlots upon which so many émigré directors worked their magic in the golden age of the studios. Everything looks like a set, and deliberately so, with the screen oscillating between classic Academy ratio and more panoramic widescreen (both 1.85 and 2.35) to differentiate between the various time periods, ancient and modern(ish).

The overriding air is one of carefully controlled craziness in which even the outbursts of sporadic violence (a spontaneous gunfight shatters the hotel's studied serenity) are politely staged. It's a rigid structure in which the players flourish, most notably Fiennes, who caught Anderson's eye in a stage production of the savage farce God of Carnage, and whose brittle manner here proves the director's perfect tool. Relishing rapid-fire dialogue that veers incongruously between the oleaginous and the obscene (his clipped diction lends bizarre gravitas to the phrase "shaking like a shitting dog"), Fiennes is in roaring form, his timing note-perfect down to the last demisemiquaver, his mannerisms piercingly angular, from the set of his arms to the arch of his back, the curl of his lip, the bristle of his manicured moustache. Even more so than the mannequins of Fantastic Mr Fox, Fiennes has the appearance of an expertly animated creation, painstakingly captured frame by frame, each gesture rich in detail.

Around him a rogues' gallery of regular players is augmented by a growing gaggle of the great and the good, with fleeting turns from Bill Murray and Owen Wilson fighting for space alongside Harvey Keitel's shaven-headed comrade-in-crime, Saoirse Ronan's perfect partner, Adrien Brody's conniving son, Willem Dafoe's feral thug, Léa Seydoux's inquisitive maid, Mathieu Amalric's elusive butler, Jeff Goldblum's Freud-like lawyer, Jason Schwartzman's third-rate concierge, and more.

Sometimes the level of fleeting celebrity spectacle threatens distraction, with too many guests for even this sprawling hotel to accommodate. Yet each time we return to Abraham's ageing narrator the story coalesces once more, allowing the deeper undercurrents of personal loss and historical tragedy to breathe, albeit briefly.

With its signature zooms, satirical tableaux, and fiercely ordered visual palette (architecture is everything, from the hairstyles to the shot compositions) this is Anderson-world writ large: a hermetically sealed environment in which reality is something you only read about in books, and the upheavals of the interwar years provide tonal rather than political background. What slices the surface is the rapier-sharp wit, with Fiennes on point at all times, a dashing foil for his director's comedic cut and thrust.

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/mar/09/the-grand-budapest-hotel-review-wes-anderson

Comentários

O Grande Hotel Budapeste é um dos filmes mais reconhecidos de Wes Anderson. Sua notoriedade se dá principalmente por motivos estéticos, visto que até os mínimos detalhes são pensados e executados de acordo com um padrão. A obra cria uma realidade a parte, em que tudo e todos adotam características, comportamentos e até histórias extremamente originais, que, apesar de fazer referência à elementos históricos e culturais, conseguem manter uma grande autenticidade.

0 notes

Text

AS MARCAS DE AUTORIA DO DIRETOR E SUAS RELAÇÕES DIALÓGICAS

Modo de filmagem

O plano frontal/horizontal da cintura para cima é recorrente, assim como cenas de objetos (mapas, diários, cartas) ou ações handmade são mostradas pelo plano de cima. Além disso, cenas em slow motion, a utilização de zoom, simetria e câmera acompanhando o movimento/olhar da personagem também são marcas presentes em filmes do Wes Anderson.

Separação cronológica e por quadros

Em Três é demais, ocorre uma separação por meses e a cada mês que passa, uma cortina com o letreiro do mês vem para introduzir o quadro a seguir. Em Os Excêntricos Tenenbaums a separação dos quadros é feita por capítulos, como se fossem de um livro. E em O hotel Budapeste a história é separada por datas.

Trilha sonora peculiar

A composição sonora vai desde músicas medievais (que não acompanham cenas medievais) até músicas de John Lennon tocadas de forma orquestral e músicas típicas dos anos 30. Isso traz uma peculiaridade às cenas pois o que está sendo tocado não necessariamente seria a melhor composição para a cena, mas de alguma forma, a composição final acaba combinando e trazendo um aspecto peculiar.

Paleta de cores

Em cada filme há uma paleta de cores muito bem definidas, entretanto, cores pastéis remetendo ao retrô e aos anos 60 são marcas do diretor.

Figurinos caricatos

Dificilmente roupas tiradas dos filmes de Wes Anderson seriam usadas no cotidiano atual. As roupas chegam a ser quase uma fantasia. São coloridas, assinadas por estilistas de grife e próprias para cada personagem. Os figurinos, embora parecidos com fantasias, conseguem descrever muito sobre a personalidade de cada personagem.

Apresentação das personagens

A apresentação das personagens é feita de forma bastante objetiva, os hobbies e peculiaridades de cada um são descritas através de takes rápidos e com letreiros característicos do diretor.

Atores

Atores como Bill Murray, Owen Wilson e Jason Schwartzman são escolhas recorrentes do diretor e aparecem em pelo menos três de suas obras.

youtube

0 notes

Text

FILMOGRAFIA DE WES ANDERSON

Filmes

Bottle Rocket/Pura Adrenalina (1994) - Curta metragem

Bottle Rocket/Pura Adrenalina (1996)

Rushmore/Três é demais (1998)

The Royal Tenenbaums/Os excêntricos Tenenbaums (2001)

The life aquatic with Steve Zissou/A vida marinha com Steve Zissou (2004)

The Squid and The Whale/A Lula e a Baleia (2005) - Produção apenas

Hotel Chevalier (2007) - Curta metragem

The Darjeeling Limited/Viagem a Darjeeling (2007)

Fantastic Mr. Fox/O fantástico Sr. Raposo (2009)

Moonrise Kingdom (2012)

Castelo Cavalcanti (2013) - Curta metragem

O Grande Hotel Budapeste (2014)

She´s funny that way/Um amor a cada esquina (2014) - Produção apenas

Isle of Dogs/Ilha de cachorros (2018)

Comerciais

My Life, My card - American Express (2004)

Softbank (2008)

Apartomatic - Stella Artois (2010)

Talk To My Car - Hyundai (2012)

Prada: Candy (2013)

Castelo Cavalcanti - Prada (2013)

Come Together - H&M (2016)

Prêmios:

1996: Melhor Diretor Estreante pelo filme Pura Adrenalina no MTV Movie Award.

1999: Melhor Diretor pelo filme Três é Demais no Independent Spirit Awards.

2007: Little Golden Lion pelo filme Viagem a Darjeeling no Festival de Veneza.

2009: Melhor Roteiro pelo filme O fantástico Sr. Raposo no Annie Awards, prêmio para animação.

2014: O Grande Prêmio do Júri pelo filme O Grande Hotel Budapeste no Festival de Berlim.

2015: Melhor Filme de Comédia ou Musical pelo O Grande Hotel Budapeste no Globo de Ouro.

2015: Melhor Roteiro Original pelo filme O Grande Hotel Budapeste no BAFTA, premiação anual britânica de cinema.

2018: Melhor Diretor pelo filme Ilha dos Cachorros no Festival de Berlim.

O diretor foi indicado diversas vezes ao Oscar, ao Globo de Ouro, entre outros prêmios. O filme Os excêntricos Tenenbaums foi indicado ao Oscar em 2001 na categoria de melhor roteiro original, assim como o filme Moonrise Kingdom em 2013. O Grande Hotel Budapeste, em 2015, dominou os prêmios técnicos e ganhou quatro estatuetas, entre elas melhor trilha sonora, melhor design de produção, melhor figurino e melhor maquiagem e cabelo.

1 note

·

View note

Text

VIDA E OBRA DE WES ANDERSON

Wes Anderson, renomado roteirista e diretor, nasceu no dia primeiro de maio do ano de 1969 na cidade de Houston. Porém, foi somente quando iniciou sua graduação em Filosofia na Universidade do Texas, que ele teve a primeira experiência com o audiovisual.

Durante esse período universitário, Wes conheceu Owen Wilson, e juntos eles começaram a produzir curtas. Uma dessas obras que ganhou destaque foi o chamado Bottle Rocket, que posteriormente originou um longa de mesmo nome.

Ao levar adiante o seu interesse pelo mundo cinematográfico, Wes Anderson revolucionou a maneira de produzir filmes. A partir de análises de suas produções, é possível notar características presentes em todas elas, como por exemplo, uma filmagem predominantemente simétrica sem profundidade, a utilização rigorosa de paletas de cores, cenas em slow motion, assim como cenas aéreas e com zoom.

Não é difícil reconhecer quando se está assistindo um filme de Wes Anderson, porque diferente de outros diretores, que têm o objetivo de fazer os espectadores se emergirem na narrativa e esquecerem que estão vendo a um filme, o design de Wes é planejado para transmitir exatamente o contrário, isso evidencia o aspecto artístico que predomina em suas obras.

0 notes

Text

SOBRE NÓS

NOSSO NOME

Qualquer narrativa depende de nós para acontecer.

São nós que amarram tramas, personagens e histórias.

NOSSA FILOSOFIA

Valorizamos o papel poderoso que o cinema pode assumir nas relações interpessoais.

Questionamos padrões. Questionamos como produções audiovisuais são feitas e como narrativas são construídas.

0 notes