Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Am Sabbat — Isidor Kaufmann (1853-1921)

signed Isidor Kaufmann (lower right)

oil on panel

58.5 by 44 cm

102 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Austrian silver Hanukah lamp, maker’s mark CW probably for Carl Warmuth Jr., Vienna, early 20th century

167 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Bezalel silver and gem-set Esther scroll case, Jerusalem, circa 1920

etched with stylized exotic birds among scrolling foliage, applied with a plaque of Esther kneeling before the King, borders of applied filigree, the top set with cabochon oval turquoises, etched in Hebrew “Scroll of Esther”, and embossed on the pull with Hebrew signature Bezalel Jerusalem, complete with scroll

length: 29 cm

130 notes

·

View notes

Photo

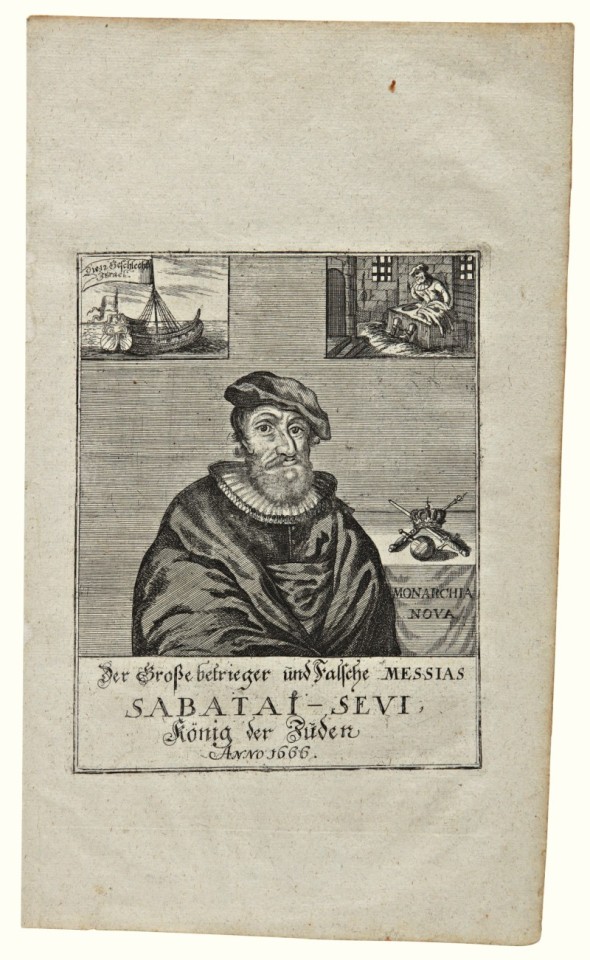

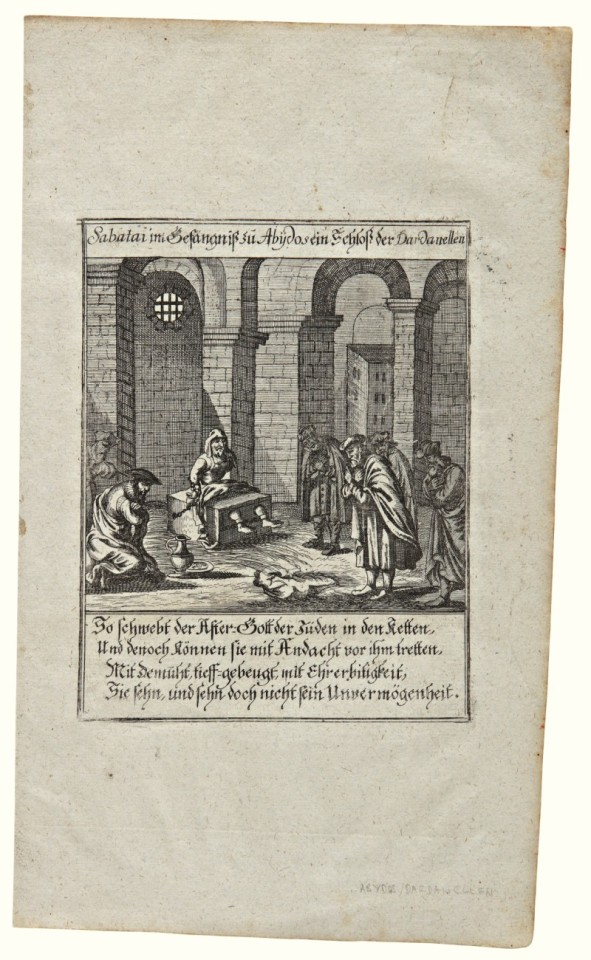

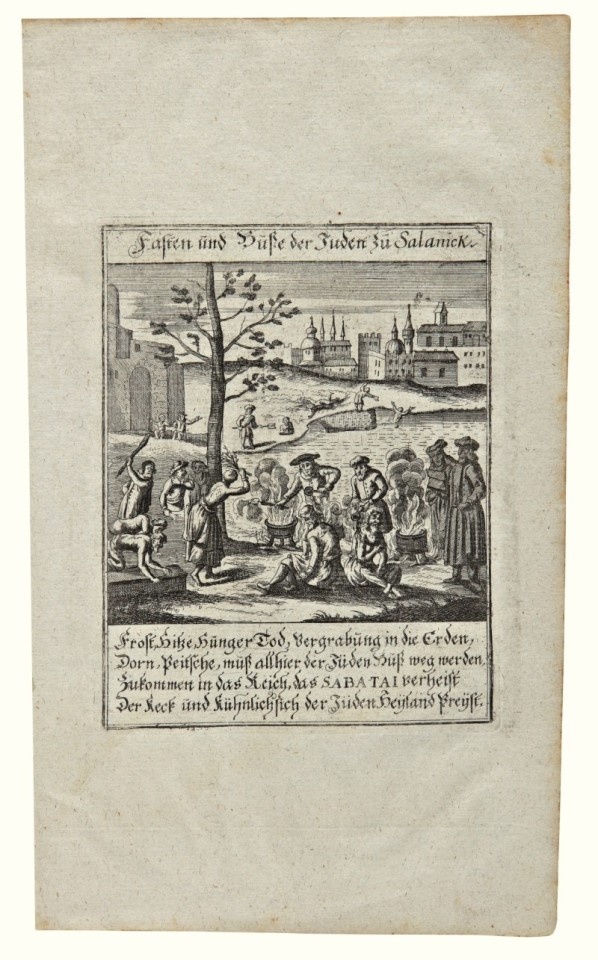

Three engravings depicting the false messiah Shabbetai Zevi and episodes relating to his life, Köthen, 1701-1703

3 broadsides (330 x 197 mm) on paper

Sabbatianism was the largest and most momentous messianic movement in early modern Jewish history. The founder of the movement was Shabbetai Zevi, who was born in Smyrna (Izmir) on 9 Av 5386 (1626). Shabbetai received a traditional Jewish education; he studied under the most illustrious rabbis of the time and seems to have been ordained as a hakham at the age of eighteen. He suffered from severe mood swings, and in his manic periods he would sometimes deliberately and spectacularly break the law of Moses. Expelled by the rabbis of various communities throughout the Ottoman Empire, Shabbetai eventually found his way to the Holy Land, where he sought out the company of the kabbalist Nathan of Gaza. The latter helped to convince Shabbetai Zevi that he was the messiah, and he proclaimed this fact in 1655, announcing the good news to the Jewish communities of Italy, Holland, Germany, and Poland, as well as to the cities of the Ottoman Empire. Messianic excitement spread like wildfire across the Jewish world, aided in part by the widespread acceptance of Lurianic Kabbalah in this period.

When Shabbetai arrived in Istanbul in January 1666, he was arrested as a rebel and imprisoned. Forced by the sultan to choose between conversion and death, he became a Muslim and apparently remained so until his demise ten years later. The news of his conversion devastated his supporters, many of whom instantly lost their faith. But astonishingly, numerous others remained loyal to Shabbetai.

The present lot comprise three very rare engravings bearing witness to the widespread and lasting impact of this popular and polarising figure. The first is a large portrait of Shabbetai Zevi with two smaller insets portraying the ship he sailed to Istanbul and his imprisonment in that city. After two months’ internment there, Shabbetai was transferred to the state prison at Abydos, on which journey some of his friends were allowed to accompany him. As a result, the Sabbatians referred to the fortress as Migdal oz (Tower of Strength). The second engraving is an image of Shabbetai in the second prison at Abydos, with his supporters paying him homage. The third depicts former followers of Shabbetai Zevi in Salonika performing acts of penance to atone for the sin of believing in a false messiah.

This group of engravings was first published in Köthen in 1701 and subsequently republished in 1702 in Anabaptisticum et Enthusiasticum Pantheon, a work compiled by Johann Friedrich Corvinus that attacked heretics, mystics, false messiahs, and anyone who was not of the strict Lutheran faith. These exceedingly rare engravings thus provide valuable insight into how Shabbetai and his movement were viewed beyond the confines of the Jewish community. [x]

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Two decorated ketubot from Tehran, 1867 and 1870

1. Celebrating the wedding of Ephraim ben Joseph and Toti bat Hakim Ezekiel on Thursday, 1 Tammuz 5627 (July 4, 1867).

2. Celebrating the wedding of Abraham ben Mordechai and Zulekha bat Arzani on Thursday, 8 Tammuz 5630 (July 7, 1870).

These ketubbot are elaborately ornamented with richly colored floral designs that amply fill the documents. This non-representational decorative program is characteristic of marriage contracts created in lands under Islamic cultural influence, where Jewish artists adopted the dominant aesthetic and refrained from incorporating figural imagery into their ketubbot and megillot. Tehran was one of the most important centers of ketubah decoration in the Middle East, and it is here that a distinctive style emerged wherein a series of text frames is surmounted by an enlarged ornamental panel.

171 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Torah finials, Silversmith: Joseph Mamun, Algeria, ca. 1869, silver, repoussé and cast

68 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A decorated ketubah from Rome, 1800

Celebrating the wedding of Shabbetai Gerson ben Moses Elijah Citoni and Mazzal Tov bat David Israel of Sienna on Wednesday, 4 Sivan 5560 (May 28, 1800).

This text of this ketubah is set within a monumental archway, which alludes to the new home that the young couple is about to establish. Vibrantly painted flowers emerge from an ornamental pot at base and embellish the inner border beside the text. A decorative frame at the top and around the outer border of the document encloses Hebrew text written in oversized, ornamental square Hebrew letters, expressing good wishes for the couple and quoting celebratory verses from the book of Ruth (4:11-12):

“All the people at the gate and the elders answered, ‘[…] May God make the woman who is coming into your house like Rachel and Leah, both of whom built up the House of Israel! Prosper in Ephrathah and perpetuate your name in Bethlehem! And may your house be like the house of Perez whom Tamar bore to Judah—through the offspring which God will give you by this young woman.’”

71 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Torah shield with three medallions, silversmith: Johann August Gebhardt (1790–1860), Berlin, Germany, 1825

Silver, repoussé, engraved, cast, and partly gilt

Inscribed in Hebrew: “Judah Leib son of Benjamin, of blessed memory, Blumenthal, before your Judgment they shall stand today, Thursday, 1 Tishrei 5585 [=1825], with his dear wife Cyrel, daughter of Isaac Itzik of blessed memory of Wurlitz”

H: 45.5; W: 25.7 cm

253 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Crescent-shaped Torah shield, Turkey, ca. 1944, Silver, cut, repoussé and engraved

Inscribed in Hebrew: “Dedicated to the holy community Beit Israel, the year 5704 [=1943/44]”

H: 25; W: 28 cm

233 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jews of Kurdistan, 1940s, by Anthony Kersting.

For much of Kurdish history, Jews were an integral part of cultural life in Kurdistan. Tradition relates that the Aramaic-speaking Kurdish Jews are the descendants of the Ten Tribes from the time of the Assyrian exile 2500 years ago. In the first century CE, the kingdom of Adiabene in Iranian Kurdistan became a Jewish one, after the monarch’s wife converted to Judaism and encouraged her subjects to do the same. It lasted until 115 CE, when Roman forces crushed its leaders, but Kurdish Jews continue to regard its descendants as part of their community. In the 17th century, Iraqi Kurdistan’s Jewish community had a female religious leader, Asenath Barzani, who was a renowned Torah scholar. Until their emigration to Israel in the 1950s, tens of thousands of Jews lived in isolated Kurdish mountain villages in harmony and friendship with their Christian and Muslim neighbors. Most worked as farmers and merchants, and their insular communities developed distinct customs, many of which have now vanished.

160 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jewish bride and her mother in Djerba, Tunisia, 1983

The Tunisian Jewish bride was hennaed first by her mother-in-law, and then the following day again by a professional artist. The bride would sleep with the henna and strings overnight. In the morning, the women come to the bride’s house to check if the henna came out nicely; if it is good, they kiss her fingers and praise her beauty. If the colour is not strong enough, then they henna her again; all in all, the bride is hennaed about four or five times over the course of a week. The Jews of Djerba continued this tradition well into the 20th century.

363 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Mur des Juifs un vendredi — The Jews wailing place, a friday.”

From P. Latteux’s Voyage en Orient (1895), in which he recounts his journey to the Middle-East, abundantly illustrated with photographs.

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

jewish wedding in vilnius, lithuanian ssr, 1968-1969

177 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Portrait of a Jewish Boy — Lazar Krestin (1868-1938), Polish

oil on canvas, 1923

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tomb of Esther and Mordechai, Hamadan, Iran. Believed by Iranian Jews to be their resting place, and a historic site of pilgrimage.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

“(Kafka) began studying Hebrew in 1921. According to his teacher, Puah Ben-Tovim, ‘he already knew he was dying’ and seemed to regard their lessons ‘as a kind of miracle cure,’ preparing ‘long lists of words he wanted to know���; rendered speechless by coughing, he would implore his teacher ‘with those huge dark eyes of his to stay for one more word, and another, and yet another.’”

— Kafka’s Last Trial (via kafkamilktea)

1K notes

·

View notes