Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

From Sales to Access: How Streaming Services Have Revolutionised Music Business Models

Main Text: Music Business Worldwide. (2018). How Streaming Will Continue to Change Everything in the Music Business. [online] Available at: <https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/how-streaming-will-continue-to-change-everything-in-the-music-business/> Accessed 5 May 2018.

Since the birth of streaming services just over a decade ago, this business model has become the topic of conversation as many debate how these platforms will shape the future of music. While many believed that these services contributed towards “devaluing art” (Rolling Stone, 2014) and the exploitation of music in return for minimal royalty payments (Guardian, 2015; Guardian, 2013), there are many benefits which remain overlooked.

As described by Denis Simms (Music Business Worldwide, 2018), streaming services have transformed the music industry from a “sales model to an access model”, whereby artists can expect to prosper from the economic benefit of long-term royalties. This access model has also had a great impact in offering consumers an attractive platform which has reduced the rate of pirated music significantly (Music Business Worldwide, 2018), contributing to a higher return in royalties.

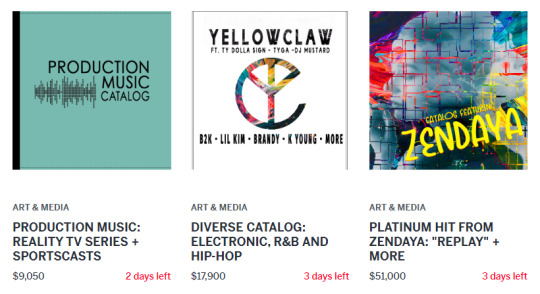

As a result, streaming has lead to the emergence of an innovative funding model which could alter the view of copyright ownership forever. Royalty Exchange, an online service providing rightsholders the ability to auction off their royalties to investors (Royalty Exchange, 2018), is a prospect that offer artists an alternate financial route to that of traditional label models (Music Business Worldwide, 2018).

(Source: Royalty Exchange, 2018)

Instead of “signing away” their copyright ownership in return for an advance (Music Business Worldwide, 2018), rightsholders retain all copyright, while receiving a fund from the investor alongside any remaining portion of royalties. If successful, this business model is likely to alter the current perceptions of copyright ownership to a serious “bankable asset” for investors (Music Business Worldwide, 2018), assigning considerable power to artists and other rightsholders.

While one could argue that this model has the potential to negatively impact record labels (Music Business Worldwide, 2018), investments of this kind are likely to be targeted at artists with established audiences and large sales forecasts. Hence, this model is more likely to be utilised as a complementary financial route to the traditional label model.

A business model that does threaten the role of labels, however, is the label services model, inspired by the world of opportunity created by streaming platforms. Artists Without A Label [AWAL] are a services label owned by Kobalt, with the aim of partnering with artists in order to develop prosperous and long-term careers in this modern industry (Kobalt Music, 2017).

The fundamental difference of label services models, like AWAL, is that artists maintain full ownership of their copyright (Music Business Worldwide, 2018); only 15% of revenues are expected once the artist obtains revenue (AWAL, 2018); ensuring financial security for artists (Music Business Worldwide, 2018).

(Source: AWAL, 2018)

As label services companies customise their services to the artist’s “individual needs” (Music Business Worldwide, 2018), this has attracted many artists which wish to bypass the assistance of a major label, however, this has not gone unnoticed. Universal, Sony and Warner Music are reported to be actively incorporating the label services model as a way of creating an opportunity in this new market (Music Business Worldwide, 2018).

In an age when the production and distribution of music is so easy, it is appropriate for there to be a number of career paths which artists can choose from. Even if the funding and label services models do capture a large segment of modern artists, there will still be those that require a traditional approach and, therefore, ensure a demand for the services of major labels.

REFERENCES

AWAL. (2018). How it Works. [online] Available at: <https://www.awal.com/how-it-works> Accessed 6 May 2018.

BBC. (2012). How Fan-Funding is Changing the Face of Music Finance. [online] Available at: <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-18788054> Accessed 6 May 2018.

Burnes, B., Graham, G., Langer, J., & Lewis, G. J. (2004). The Transformation of the Music Industry Supply Chain: A Major Label Perspective. International Journal of Operations & Production Management. 24

(11). p.1087-1103.

Financial Times. (2010). The Music Industry’s New Business Model. [online] Available at: <https://www.ft.com/content/92d98d1c-bae9-11df-9e1d-00144feab49a> Accessed 6 May 2018.

Guardian, The. (2014). Can Fan Campaigns Reinvent the Music Industry? [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/music/2014/jun/17/can-fan-campaigns-reinvent-the-music-industry-kickstarter-crowdfunding> Accessed 6 May 2018.

Guardian, The. (2008). Don’t Just Buy the Music, Fans Told - Now You Can Invest in Big Names of the Future. [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/aug/27/musicindustry.investing> Accessed 6 May 2018.

Guardian, The. (2015). Prince Pulls Music from All Streaming Services Except Tidal. [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/jul/02/prince-pulls-music-from-all-streaming-services-except-tidal> Accessed 6 May 2018.

Guardian, The. (2013). Thom Yorke blasts Spotify on Twitter as He Pulls His Music. [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/jul/15/thom-yorke-spotify-twitter> Accessed 6 May 2018.

Kobalt Music. (2017). AWAL Demystifies Streaming Data for Independent Artists. [online] Available at: <https://www.kobaltmusic.com/press/awal-de-mystifies-streaming-data-for-independent-artists> Accessed 6 May 2018.

Music Business Worldwide. (2018). Can this Company Attract £1BN for Songwriters in the Coming Years? [online] Available at: <https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/can-company-attract-1bn-songwriters-coming-years/> Accessed 5 May 2018.

Music Business Worldwide. (2018). How Streaming Will Continue to Change Everything in the Music Business. [online] Available at: <https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/how-streaming-will-continue-to-change-everything-in-the-music-business/> Accessed 5 May 2018.

Music Business Worldwide. (2017). Royalty Exchange Raises $6.4M as Industry Veterans Join Its Board. [online] Available at: <https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/royalty-exchange-raises-6-4m-industry-veterans-join-board/> Accessed on 6 May 2018.

Music Business Worldwide. (2017). Where is the Accountability in a ‘Label Services’ Deal? [online] Available at: <https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/accountability-label-services-deal/> Accessed 6 May 2018.

Music Week. (2018). ‘You Don’t Need a Major Label to Have Success’: Why the Label Services Sector is Bigger Than Ever. [online] Available at: <http://www.musicweek.com/labels/read/you-don-t-need-a-major-label-to-have-success-why-the-label-services-sector-is-bigger-than-ever/071315> Accessed 6 May 2018.

Rolling Stone. (2014). Taylor Swift’s Label Pulled Music from Spotify for ‘Superfan Who Wants to Invest,’ Says Rep. [online] Available at: <https://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/taylor-swift-scott-borchetta-spotify-20141108> Accessed 6 May 2018.

Royalty Exchange. (2018). [online] Available at: <https://www.royaltyexchange.com/> Accessed 5 May 2018.

Virgin. (2014). How Marillion Pioneered Crowdfunding in Music. [online] Available at: <https://www.virgin.com/music/how-marillion-pioneered-crowdfunding-music> Accessed 6 May 2018.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ARTificial Intelligence: The Hologram Revolution of Live Music

Main text: Holt, F. (2010). The Economy of Live Music in the Digital Age. European \Journal of Cultural Studies. 13 (2). P.243-261.

“Maybe the future of live isn’t live at all” (Billboard, 2012)

As expressed by Holt (2010; Kopiez, 2015), there is a significant importance surrounding live performance and visuals as complementary components of the musical experience. While recorded music is a timeless product that consumers can indulge in upon demand, there is an undeniable exclusivity embodying the live experience due to its inability to be replicated beyond that “time and space” (Holt, 2010, p.244).

The term “live” once referred to a performance that was created and played in real time, with no “pre-produced” material (Holt, 2010, p.245), however, the adoption of technology in performance has since normalized the use of “pre-produced” sounds and effects. Copious technological developments including the microphone, amplifiers, MIDI controllers and even digital audio workstations [DAWs] have been big contributors to the newfound creativity in live music (NEXT, 2015), empowering artists regardless of their budget or audience.

In contrast, it could be suggested that the most recent technological developments involved in the live sector are actually working to empower the consumer (Hypebot, 2017). Live-streaming of events like Coachella and Glastonbury (Hypebot, 2017) now provide music consumers with the opportunity to participate in this live experience without leaving their houses. While this is a relatively detached experience, the LA Times (2018) have reported that over forty-one million people viewed Coachella in its premier weekend of 2018. In consideration of the festival’s capacity, 125,000 people (NBC San Diego, 2017) represented approximately only 0.3% of the 41 million viewers, leading many to question whether technology has the potential to harm ticket sales (Hypebot, 2017).

The technological development that is provoking the thoughts and opinions of many, however, is; the Hologram (Billboard, 2012). Michael Jackson and Tupac are just two of many notorious instances in which this “digital resurrection” (Billboard, 2017) has been showcased and although it requires large financial investment, there is a possibility that holograms will, one day, become an affordable and normalised part of performance (Billboard, 2017; Noisey 2017).

(Source: Billboard, 2017)

Due to the vital condition that an artist must be alive to perform, this significantly reduces the lifespan of an individual live experience, making it extremely exclusive. With the ability to “resurrect” an artist through technology, however, this offers unimaginable opportunities for the industry to profit, as well as the chance for consumers to engage in an event that was once impossible. Although holograms are not simply restricted to the resurrection of deceased artists, are there moral implications for profiting from the recreation of another’s identity (Noisey, 2017) and is this really a live experience (Billboard, 2012)?

Billboard (2012) argues that while holograms hold big potential, this technology may be received in an uneasy manner by loyal fans. The Tupac hologram of Coachella 2012 has been described as similar to a “stage prop” (Billboard, 2012), and while this moment defined an incredible revolution in performance, it is appropriate to suggest that the celebration of an artist should remain exclusive to those present in that “time and space” (Holt, 2010, p. 243).

Holt (2010, p. 245) suggests that it is a “co-presence” among the physical environment of a performance which truly makes it live, and as holograms embody the artist’s presence it could be suggested that this truly does fit the description of live.

REFERENCES

BASE Hologram. (2018). BASE Entertainment Announces New Cutting Edge Live Entertainment Company: BASE Hologram. [online] Available at: <https://basehologram.com/news/base-entertainment-announces-new-cutting-edge-live-entertainment-company-base-hologram> Accessed 3 May 2018.

Bennett, R., J., & Creswell Jones, A. (2015). The Digital Evolution of Live Music. Kidlington: Chandos Publishing.

Billboard. (2017). Are Biggie and Bowie Next Up For the Hologram Treatment. [online] Available at: <https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/magazine-feature/7717065/holograms-peter-martin> Accessed 3 May 2018.

Billboard. (2012). Opinion: The Problem With The Tupac Hologram. [online] Available at: <https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/the-juice/494288/opinion-the-problem-with-the-tupac-hologram> Accessed 2 May 2018.

Billboard. (2017). Tupac, Michael Jackson, Gorillaz & More: A History of the Musical Hologram. [online] Available at: <https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/pop/7717042/musical-holograms-history-dead> Accessed 2 May 2018.

Eco-Bridge. (2016). Digital Disruption: The Music Industry. [online] Available at: <http://www.eco-bridge.com/2016/08/08/digital-disruption-the-music-industry/> Accessed 4 May 2018.

ET Canada. (2018). Roy Orbison Returns to the Stage as a Hologram as Glastonbury 2019 Rumours Continue. [online] Available at: <https://etcanada.com/news/294829/roy-orbison-returns-to-the-stage-as-a-hologram-as-glastonbury-2019-rumours-continue/> Accessed on 2 May 2018.

Eventbrite. (2018). An Insider’s Look at Live Events & The Music Industry. [online] Available at: <https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/blog/live-events-the-music-industry-ds00/> Accessed 3 May 2018.

Frith, S. (1998). Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Guardian, The. (2017). UK Music Industry Gets Boost From 12% Rise in Audiences of Live Events. [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/jul/10/uk-music-industry-gets-boost-from-12-rise-in-audiences-at-live-events> Accessed 4 May 2018.

Holt, F. (2010). The Economy of Live Music in the Digital Age. European Journal of Cultural Studies. 13 (2). P.243-261.

Hypebot. (2017). How Do Advances In Technology Change the “Live Experience”. [online] Available at: <http://www.hypebot.com/hypebot/2017/10/how-do-advances-in-technology-change-the-live-experience.html> Accessed 3 May 2018.

Kopiez, R., Platz, F. (2015). When the Eye Listens: A Meta-Analysis of How Audio-Visual Presentation Enhances the Appreciation of Music Performance. Music Perception. 30 (1). P.71-83.

LA Times. (2018). Coachella Racks Up a Record 41 Million-plus Livestream Views on YouTube. [online] Available at: <http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/la-et-entertainment-news-updates-2018-coachella-racks-up-record-41-1524000028-htmlstory.html> Accessed 5 May 2018.

NBC News. (2016). How Virtual Reality is Re-defining Live Music. [online] Available at: <https://www.nbcnews.com/mach/innovation/how-virtual-reality-redefining-live-music-n687786> Accessed 3 May 2018.

NBC San Diego. (2017). Highest Attendance Ever Expected at Coachella Festival. [online] Available at: <https://www.nbcsandiego.com/news/california/Highest-Attendance-Ever-Expected-at-Coachella-Festival-419329504.html> Accessed 5 May 2018.

NEXT. (2015). The History (and Future) of Live Music. [online] Available at: <https://howwegettonext.com/the-history-and-future-of-live-music-147ecde437b7> Accessed 5 May 2018.

Nielsen. (2016). Keeping It Real: Understanding Live Event Behaviour and Sponsorship Opportunities. [online] Available at: <http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2016/keeping-it-real-understanding-live-event-behavior-and-sponsorship-opportunities.html> Accessed 3 May 2018.

Noisey. (2017). Inside the Shady World of the Musical Hologram. [online] Available at: <https://noisey.vice.com/en_uk/article/434vv3/musical-hologram-usa-tupac-whitney-houston-digital-domain-pulse-evolution> 3 May 2018.

Odyssey. (2016). The Importance of Experiencing Live Music. [online] Available at: <https://www.theodysseyonline.com/appreciate-live-music> Accessed 3 May 2018.

Undefeated, The. (2017). The Strange Legacy of Tupac’s ‘Hologram’ Lives On Five Years After Its Historic Coachella Debut. [online] Available at: <https://theundefeated.com/features/the-strange-legacy-of-tupacs-hologram-after-coachella/> Accessed 2 May 2018.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Transparent Future For Copyright: Is AMRA The Answer?

Main text: Kobalt Music. (2017). A New Type of Collection Society for the Global Digital Streaming Market. [online] Available at: <https://www.kobaltmusic.com/blog/a-new-type-of-collection-society-for-the-global-digital-streaming-market> Accessed on 26 April 2018.

The music industry is notorious for its non-disclosure, complex nature, however, the digitalisation of music has indicated that an innovative but simplified system is essential for accurate royalty collection and payment (Kobalt, 2017). Within the past several years, ‘transparency’ has become a concept conquering the music industry (NPR Music, 2015), declaring a congruent business mission for many sectors and organisations as they prepare to accustom to the digitalised world.

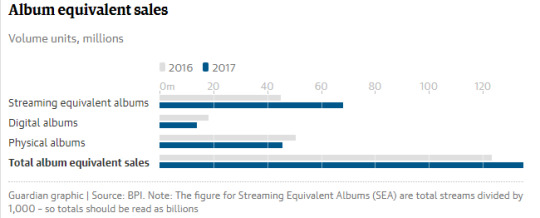

In 2017, BPI recorded the quickest growth in music consumption in the UK, lead by a rise in the use of streaming services (Guardian, 2018) with figures exceeding physical and digital sales for the first time (Independent, 2017). Although this format still has a long way to go before surpassing the revenue figures collected in the industry’s healthiest period (IFPI, 2003), streaming is likely to be an important form of musical consumption for some years. Hence, it is within the industry’s best interests to adapt its operations to these new trends in consumer behaviour.

(Source: Guardian, 2018).

The current dilemma with the collection of digital royalties is the result of an outdated model being applied in an age that requires modernized approaches (Huffington Post, 2016). Since the emergence of Spotify in 2008, there has been an evident rise in the uncertainty of artists, forming the popular perception that misconduct is carried out by streaming services regarding royalty payments (Independent, 2014). However, it could be suggested that the focal point of the industry’s concern should be on the operations of performing rights organizations [PROs] and their contributions to this issue (Kobalt, 2017).

At present, PROs operate in fragmented and localised systems inappropriate for the collection of digital streaming royalties which necessitate the ability to collect on a global scale (Kobalt, 2017). As a consequence, PROs are unable to sufficiently track the increasing number of revenue streams (Kobalt, 2017), causing payments to take long periods of time to be processed, while some royalties are even lost (Wired, 2015).

Within recent years, much action has taken place to modernize the collection process of royalties, including the ‘Transparency in Music Licensing and Ownership Act’ (NPR Music, 2017), the ‘Music Modernization Act’ (Billboard, 2018) and the Global Repertoire Database project [GRD] (PRS, 2011). While the former two projects are currently in their infancy, the GRD project, established in 2009, failed due to a lack of funding and consensus among publishing companies and PROs (Complete Music Update, 2014).

While these projects all sought a similar goal; a global database for “quick and efficient compensation” (PRS, 2011); AMRA, a digital collection society launched by Kobalt is the first of its kind (Kobalt, 2017). AMRA combines high quality technology with a globalized system in order to quickly, efficiently and accurately collect and distribute payments by communicating directly with digital service providers [DSPs] (Kobalt, 2017). This approach also offers artists access to data, enabling them to monitor the royalty collection process (Kobalt, 2017), minimising the aforementioned issue of uncertainty.

(Source: Kobalt Music, 2017)

On the contrary, by revolutionizing the collection of royalties, AMRA is likely to threaten the role of PROs, or in an extreme case render these organizations redundant (Complete Music Update, 2014), as the industry adapts to this innovative collection system. Similar to arguments posed surrounding the ‘Music Modernization Act’, AMRA has the potential to create an anti-competitive environment (Billboard, 2018) due to the ever-growing demand for one central database responsible for the collection of royalties (Complete Music Update, 2014).

Despite these possible implications for the music industry, it is clear that a central database is becoming increasingly crucial as technology transforms its operations and broadens its revenue streams, with no signs of stalling (Guardian, 2018). While AMRA has far to go before becoming a collection society that monopolises and threats the industry, it is going in the right direction to strengthening trust in artists and creating a transparent royalty payment experience.

REFERENCES

AMRA. (2018). Launch Statement. [online] Available at:<https://www.amra.com/#launch-statement> Accessed on 26 April 2018.

Artist Rights Watch. (2017). Content Creators Coalition (c3) Warns Congress About Artist and Songwriter Opposition To “Transparency in Music Licensing and Ownership Act”. [online] Available at: <https://artistrightswatch.com/category/transparency-in-music-licensing-and-ownership-act/> Accessed on 25 April 2018.

Billboard. (2018). Music Modernization Act Expected to be Introduced in Congress Tuesday. [online] Available at: <https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/8300501/music-modernization-act-introduced-congress-tuesday> Accessed on 25 April 2018.

Complete Music Update. (2014). PRS Confirms Global Repertoire Database “Cannot” Move Forward, Pledges to Find “Alternative Ways”. [online] Available at: <http://www.completemusicupdate.com/article/prs-confirms-global-repertoire-database-cannot-move-forward-pledges-to-find-alternative-ways/> Accessed on 24 April 2018.

Digital Music News. (2017). War Erupts Over Whose Global Music Rights Database is Better. [online] Available at: <https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2017/08/04/riaa-ascap-bmi-congress-shared-music-database/> Accessed on 24 April 2018.

Guardian, The. (2018). Digital Streaming Behind Biggest Rise in the UK Music Sales for Two Decades. [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/jan/03/digital-streaming-behind-biggest-rise-in-uk-music-sales-for-two-decades> Accessed on 26 April 2018.

Guardian, The. (2008). What Does the Future Hold for Songwriters’ Royalties? [online] Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2008/aug/21/whatdoesthefutureholdfor> Accessed on 25 April 2018.

Huffington Post, The. (2017). How the Department of Justice is Shaping the Future of Music. [online] Available at: <https://www.huffingtonpost.com/zach-katz/how-the-department-of-jus_b_11427250.html> Accessed on 24 April 2018.

IFPI. (2003) The Recording Industry World Sales: 2002. [online] Available at: <http://www.ifpi.org/content/library/worldsales2002.pdf> Accessed on 26 April 2018.

Independent, The. (2017). Streaming Set to Overtake Physical Music Sales in the UK. [online] Available at: <https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/streaming-physical-sales-uk-music-industry-vinyl-spotify-apple-deezer-ed-sheeran-bpi-a7681431.html> Accessed on 26 April 2018.

Independent, The. (2014). Taylor Swift Reveals Why She Quit Spotify: ‘I Will Not Dedicate My Life’s Work To An Experiment’. [online] Available at: <https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/taylor-swift-reveals-why-she-quit-spotify-i-will-not-dedicate-my-lifes-work-to-an-experiment-9845941.html> Accessed on 30 April 2018.

Kobalt Music. (2017). A New Type of Collection Society for the Global Digital Streaming Market. [online] Available at: <https://www.kobaltmusic.com/blog/a-new-type-of-collection-society-for-the-global-digital-streaming-market> Accessed on 26 April 2018.

MIC Coalition. (2017). Transparency in Music Licensing and Ownership Act Promotes a Vibrant Music Licensing Marketplace. [online] Available at: <https://mic-coalition.org/news-posts/transparency-music-licensing-ownership-act-promotes-vibrant-music-licensing-marketplace/> Accessed on 26 April 2018.

Music Business Worldwide. (2015). Kobalt’s AMRA Signs Its First Global Collection Deal… With Apple. [online] Available at: <https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/kobalts-amra-signs-first-global-collection-deal-apple/> Accessed on 26 April 2018.

Music Business Worldwide. (2018). Spotify Sued for $1.6 Billion By Wixen in Huge Copyright Infringement Lawsuit. [online] Available at: <https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/spotify-sued-for-1-6bn-by-wixen-in-huge-copyright-infringement-lawsuit/> Accessed on 25 April 2018.

Music Business Worldwide. (2017) The UK Music Industry Tried to Agree a ‘Transparency Code’ for Streaming Royalties. It Collapsed - Here’s Why. [online] Available at: <https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/the-uk-music-industry-tried-to-agree-a-transparency-code-for-streaming-royalties-it-collapsed-heres-why/> Accessed on 24 April 2018.

Music Business Worldwide. (2016). Who Will Build the Music Industry’s Global Rights Database? [online] Available at: <https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/who-will-build-the-music-industrys-global-rights-database/ > Accessed on 24 April 2018.

NPR Music. (2015). Is Transparency The Music Industry’s Next Battle? [online] Available at: <https://www.npr.org/sections/therecord/2015/07/14/422707429/is-transparency-the-music-industrys-next-battle> Accessed 1 May 2018.

NPR Music. (2017). New Bill Calling for Transparency in Music is Surprisingly Opaque. [online] Available at: <https://www.npr.org/sections/therecord/2017/08/01/540655528/new-bill-calling-for-transparency-in-music-is-surprisingly-opaque> Accessed on 25 April 2018.

PRS. (2011). Global Repertoire Database Working Group Launches. [online] Available at: <https://www.prsformusic.com/press/2011/global-repertoire-database-working-group-launches> Accessed on 25 April 2018.

Reuters. (2011). Music Industry Working on Global Copyright Database. [online] Available at: <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-rights/music-industry-working-on-global-copyright-database-idUSTRE70K56420110121> Accessed on 25 April 2018.

WIPO Magazine. (2015). Streaming and Copyright: A Recording Industry Perspective. [online] Available at: <http://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2015/02/article_0001.html> Accessed on 26 April 2018.

Wired. (2015). Kobalt Changed the Rules of the Music Industry Using Data - And Saved It. [online] Available at: <http://www.wired.co.uk/article/kobalt-how-data-saved-music> Accessed on 1 May 2018.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Commodification of Culture: Popular Music Culture and Marketing

Main text: Stratton, J. (1983). Capitalism and Romantic Ideology in the Record Business. Popular Music. 3. Pg 143 - 156.

The industrialisation of music emerged in the late nineteenth century upon the inflation of the availability of new sound technologies, the gramophone and the cylinder (Libraries). Due to the utilisation of affordable raw materials, these new musical products were able to be mass-produced, simultaneously repositioning music from an affluent market, to a large middle class audience (Libraries).

Akin to businesses of contrasting industries, as the music industry’s audience massified, this major increase in demand required a profitable solution that would meet the needs and exceed the expectations of the masses. This solution became the standardisation of music (Stratton, 1983, pg 143) which made the music publishers of Tin Pan Alley (Libraries) main sources of the formation of popular culture in music.

As expressed by Stratton (1983, pg 149, 150), the capitalist economic system of the major record company poses as a paradox for the music industry, one which commodifies music as a standardised product to market to a wide demographic, but also one which requires innovation through features of romantic culture such as self-expression and individuality in order to continue to generate revenue.

Mass-production methods like standardisation have been described as Ford-ist, (Negus, 1999, pg 17) “factory-like” processes (Meiers, 2017, pg 22) whereby the majority of commercial music is similar through a ‘formulaic’ pattern (Stratton, 1983, pg 148) often found within song structure, lyrics and song lengths. Philosopher Theodor W. Adorno argued that this process of capitalist production within popular culture promotes a passive experience which lacks the stimulation of critical thinking (Stratton, 1983, pg 143) as all popular music is similar in ways and, therefore, “pre-digested” material (Listen To Better Music, 2014).

From a marketing stance, applying a specific formula to a product which is targeted to an undifferentiated audience is controversial to the essence of the marketing concept. In order to fully satisfy customer needs profitably (Jobber, 2016, pg 5), varying customer demands must be taken into account by segmenting markets into those that share similar characteristics (Jobber, 2016, pg 204).

Despite this, the record industry operates in a production oriented fashion, with the mission of aggressively manufacturing and selling music in an efficient and cost-effective manner (Jobber, 2016, pg 6-8). However, in order to be effective as a business, marketing aspects need to be considered in order to ensure the provision of products that meet consumer needs. According to Jobber (2016, pg 12) if a business is efficient but lacks effectiveness, the business will gradually diminish as competitors offering effective products and services are likely to grasp the attention of that market.

The market oriented Information Technology [IT] sector has become a strong competitive force against the modern music industry (Hesmondhalgh, 2017, pg 2) with its mission of implementing innovation into its products and services, revolutionising the consumer experience and detaching artists from the capitalism of record companies. Among its arrival in June 1999, infamous peer-to-peer network Napster caused much disruption by arguably de-commodifying music, (Hesmondhalgh, 2017, pg 9) exposing consumers worldwide to a limitless library of free musical works.

However, in the context of Adorno’s theories on popular culture, if all popular music are standardised products with minor differential factors (Stratton, 1983, pg 146), then are IT companies really offering choice?

REFERENCES

Denisoff, R. S. (1975). Solid Gold: The Popular Record Industry. New Brunswick: Transaction Books.

Ellis-Chadwick, F., & Jobber, D. (2016). Principles and Practice of Marketing. 8th ed. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education.

Heathwood Press. (2013). On Adorno’s Critique of Popular Culture and Music. [online] Available at: <http://www.heathwoodpress.com/on-adornos-critique-of-popular-culture-and-music/> Accessed on 15 April 2018.

Hermogen. (2012). Why Capitalism is Inherently Romantic. [online] Available at: <http://hermogen.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/why-capitalism-is-inherently-romantic.html> Accessed on 15 April 2018.

Hesmondhalgh, D., & Meiers, L, M. (2017). What the Digitalisation of Music Tells Us About Capitalism, Culture and the Power of the Information Technology Sector. Information, Communication & Society. Pg 1 - 16.

Huffington Post, The. (2015). Can Marketing Improve Capitalism? [online] Available at: <https://www.huffingtonpost.com/fixcapitalism/can-marketing-improve-cap_b_8516126.html> Accessed on 15 April 2018.

Libraries. 6.2 The Evolution of Popular Music. Understanding Media and Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication. [online] Available at: <http://open.lib.umn.edu/mediaandculture/chapter/6-2-the-evolution-of-popular-music/> Accessed on 17 April 2018.

Listen To Better Music. (2014). On Popular Music, by Theodor Adorno. [online] Available at: <https://listentobettermusic.wordpress.com/2014/08/16/on-popular-music-by-theodor-adorno/> Accessed on 15 April 2018.

Marketing Journal, The. (2016). The Relationship Between Marketing and Capitalism. [online] Available at: <http://www.marketingjournal.org/the-relationship-between-marketing-and-capitalism-phil-kotler/> Accessed on 15 April 2018.

Meiers, L, M. (2017). Popular Music as Promotion: Music and Branding in the Digital Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Midnight Media Musings. (2014). Social Media and The Hegemony of Capitalism - A Digital Essay. [online] Available at: <https://midnightmediamusings.wordpress.com/2014/10/12/social-media-and-the-hegemony-of-capitalism-a-digital-essay/> Accessed on 15 April 2018.

Musicology for Everyone. (2016). How Tin Pan Alley Transformed the Popular Music Industry. [online] Available at: <http://music.allpurposeguru.com/2016/07/how-tin-pan-alley-transformed-the-popular-music-industry/> Accessed on 17 April 2018.

Negus, K. (1999). Music Genres and Corporate Cultures. London: Routledge.

Open Democracy UK. (2012). Capitalism, Creativity, and the Crisis in the Music Industry. [online] Available at: <https://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/jeremy-gilbert/capitalism-creativity-and-crisis-in-music-industry> Accessed on 15 April 2018.

Roadrunner Theorist, The. Pseudo-Individualisation. [online] Available at: <https://roadrunnertheory.wordpress.com/2014/03/08/pseudo-individualization/> Accessed on 15 April 2018.

Shapero, D. (2015). The Impact of Technology on Music Stars’ Cultural Influence. Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications. 6 (1). Pg 1, 2.

Social Revolution. (2017). Music and the Decline of Capitalism. [online] Available at: <https://socialistrevolution.org/music-and-the-decline-of-capitalism> Accessed on 15 April 2018.

Stanford Business. (2005). When Does Culture Matter in Marketing? [online] Available at: <https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/when-does-culture-matter-marketing> Accessed on 17 April 2018.

Stratton, J. (1983). Capitalism and Romantic Ideology in the Record Business. Popular Music. 3. Pg 143 - 156.

4 notes

·

View notes