Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

*pre act 1, somewhere in the outerplanes or whatever* gods: what the hells are the dead 3 doing now?? what is that?? a netherbrain?? ugh right then, what are we gonna do about it shar: i have a plan SO EVIL AND PERFECT and a chosen locked and loaded she's already on her way to retrieve that stupid githyanki prince and then im going to fucking destroy that asshole ketheric

mystra: bitch please the only one around here with a shiny red fix it button is me. when i tell you my former chosen is obsessed with me. no way will he deny me, all i gotta do is ask and he'll detonate the problem in one go. ace in the hole.

Jergal [a big fan of the avengers]: i have a plan to bring together a group of of remarkable people to see if they could become something more. To see if they could work together when we need them to, to fight the battles that we never could.

gods: ugh shut the hell up jergal this is basically your fault

Jergal: im stealing all your feral chosen and you can't stop me

silvanus: would you like a bear in this trying time?

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

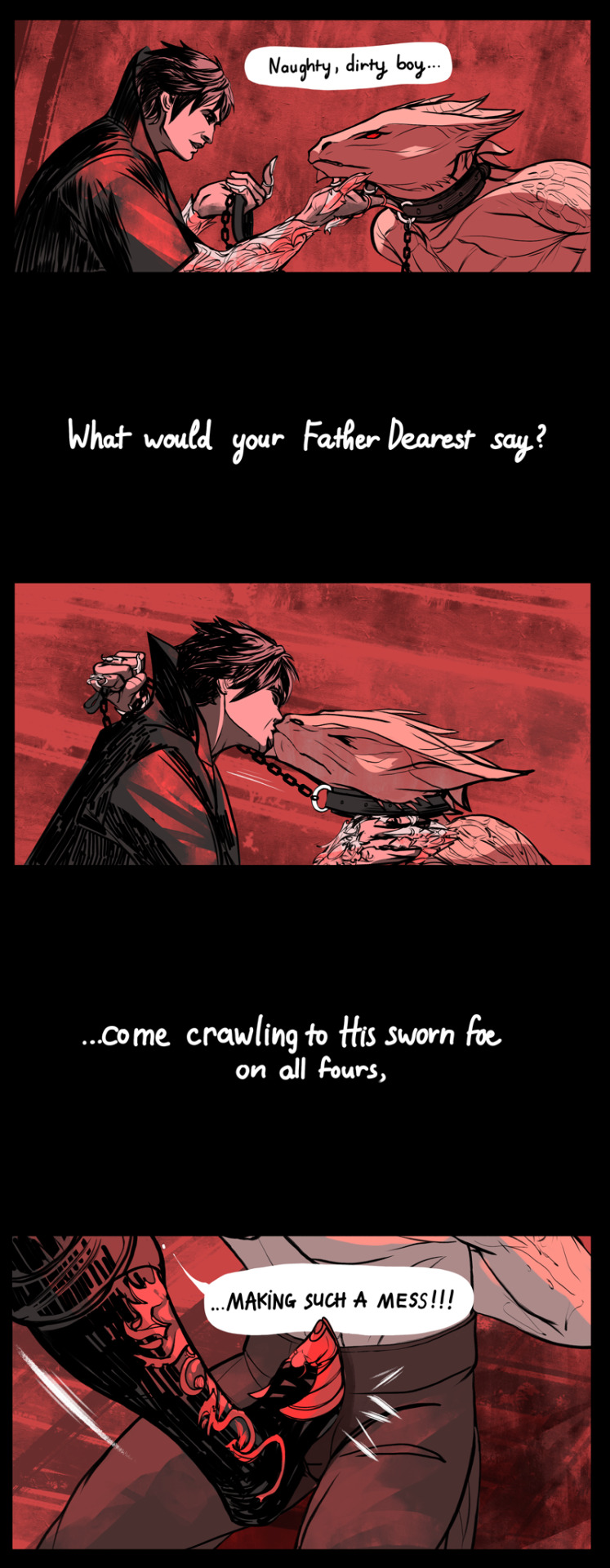

Durge came to his dearest and nearest to help dealing with his episode. Gortash was happy to give a hand, not for free though.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

if I were an npc in skyrim I would never leave my house because there are giant spiders out there. My one line of radiant dialogue would be "I don't leave the house, there's giant spiders out there."

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

bitches be like "I love this person more than most of my family I want to hold them forever" and it's a fictional character with twenty lifetimes worth of trauma

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

Voluntary Hell in Inferno (bib. Included)

*Disclaimer: Old College Paper!*

The concept of Hell is like an allegory of sorts to explain the afterlife of people who have sinned against God, never having been forgiven or never forgiving themselves. A common church teaching would also say that Hell is just to be without God, fire and brimstone not included, though that wouldn’t be the majority’s consensus. The Hell created and reworked by Dante in the first part of The Divine Comedy isn’t just about being alone and without God; it is about punishment and a refusal to accept the faults that transpired in the sinners’ lives. This a world of choice and self-deception, the inability to finally grieve the life they lost and look to the future and be forgiven, only able to retell the same distorted stories and comfort themselves with the knowledge that they weren’t wrong. Sinners like Ulysses, a famous player in the Trojan War, are examples of the denizens of Hell not necessarily feeling guilty for their actions in life. Ulysses, like many Greek heroes, suffered for his own hubris and deception in life, condemned to burn forever.

In the Twenty-sixth canto of the Inferno, Dante and Virgil continue to meet the fraudulent sinners and, amongst the flames, they meet Ulysses and Diomed. The sinners here burn for their sins, however, two are conjoined in one flame for both incurring God’s wrath during the Trojan War. Virgil identified them by name and by crime saying, “’In their flame they

mourn the stratagem of the horse that made a gateway through which the noble seed of Rome came forth’”(Inf. 26 58-60), which is an obvious reference to the Trojan Horse. Ulysses and Diomed are the ones responsible for this creation and strategy, deceiving the Trojans and lying about its significance, claiming it was a symbol of Athena and that possessing it would gain her favor in the war. This was all a trick, of course, as there were soldiers inside, and they attacked the Trojans after breaking out. Virgil chastises them for this deception and poses as Homer to do so, clearly not ascribing to the motto that “all’s fair in love and war,” while Dante seems to sympathize with them, as he does for many of the sinners he meets, saddened by how easily people slip into sin and pay for eternity. A modern audience, however, with the lack of literary and historical context that Dante has, would have no idea who many of these people were and would only be able to pass judgement based on what they have read in the poem. While the trope of the Trojan Horse can be considered common knowledge for many people, the context of the war and heroes may not mean as much, especially when it’s debated a debated subject as to whether or not the war ever happened. As far as an ignorant audience is concerned, the sinners are bad, as evidenced by them being in Hell, and they should just follow along for the ride. The reader must look at Dante as the expert during this expedition and have faith that their fellow man knows what he’s talking about.

Humans, obviously, are multifaceted beings, never able to be defined by one action or personality trait, and Dante knew this. People make mistakes and are never perfect, many repent and right their wrongs, while others are content with the wrongs they’ve done and never change. Despite knowing this, he did weave an epic about a hell broken down into several circles, some containing their own sub-circles, and sinners were punished according to one specific sin they committed in life. Dante never clearly defines how the hierarchy of sins work per sinner,

although the circles do deal with more severe sins the further down the reader goes. The lack of a clear categorization can really be attributed to creative liberty; Dante had to put certain people in specific circles in order to drive his poem, purposefully ignoring the fact the one person can easily commit multiple sins and technically have claim to multiple circles. This goes back to Ulysses in particular, he is a thief in God’s eyes and committed fraud, but he was also prideful and arrogant. Like Adam and Eve, Ulysses wanted the knowledge of the world, only he did it at the expense of his family and fellow soldiers. This is why Virgil reprimands him so much, as his hero, Aeneas, was the exact opposite; compared to the empathetic and sometimes scatter-brained hero of the Aeneid, anyone would look like a villain.

Focusing on Ulysses’ pride, he admitted to leaving his family behind, blaming his “’fervor... to gain experience of the world and learn about a man’s vices, and his worth’” (Inf. 26 97-99). This shifting of blame is a parallel to Francesca much earlier in the poem, blaming both love and the story of Lancelot and Guinevere. Dante’s Hell is filled with people unable to accept their own mistakes or see why they were misguided, therefore, never finding redemption for themselves and getting a chance to go to Heaven. The sinners are also unaware of what’s happened in the world since they died, allowing them to continue reaffirming themselves with their delusions that they were in the right and were unfairly punished. For them, reality is only what they make it, or what Dante says they do. Ulysses’ reality was one of him being a man of great intellect and that he deserved to know everything, but if he had listened to his own speech, he would’ve realized how he had flown too close to the sun and damned himself and his crew to a watery grave. Through his own death, he should have seen that seen that he took his ambitions too far, but he feels no guilt for it. There is no redemption for him, as he’s so lost in his own fantasy that he can’t make out the truth, like dying at sea, he went overboard. Though his actions

aren’t commendable, they don’t seem very condemnable either; the only voice that is really speaking is Dante, so the source is biased. To put it simply, humans live in a cycle of success and error; Ulysses had succeeded in his goals to find the end of the world, his error was how he had gone about it.

Traversing a Hell pioneered by Virgil and remade by Dante, a reader is transported to a realm of despair and vice, just as confused as the poet’s younger self. The sinners condemned attempt to garner sympathy from the reader and Dante, while also maintaining the façade that they are content to suffer, even if they claim to be unjustly persecuted. Hell is a contradiction, teeming with figures from history and literature that refuse to forgive their enemies or themselves, while bombarding the audience with how they were wronged and really didn’t deserve their eternal sentence. They all continue to exist in sin by choice, whether they are still aware of that or not, as Christianity teaches its followers that all will be forgiven and that God’s love is unconditional, but it would appear that too many have been drowning in their own selfpity for so long that they can’t remember the Word of God. Dante is their last chance at living again, forever immortalizing them and their stories through poetry. With any luck, the Inferno will only be the first part in every sinner’s journey to be redeemed in God’s eyes.

Bibliography: Alighieri, Dante, et al. “Canto 26.” The Inferno, First ed., Anchor Books, 2000, pp. 475–485.

0 notes

Text

Pietà Analysis Paper (bib. Included)

*Disclaimer: it's an old assignment that I didn't put the most effort into, just wanted to post it for public viewing!*

The emotion and fluidity of movement of figures set in stone, in contrast with the rigidity of the material, create the illusion of the middle ground between life caught in a candid moment and subjects being frozen in time. Stone, on its own, is lifeless. There is no varnish or amount of polishing that can make it otherwise. It is then that an artist must be employed, commissioned to convince an audience into believing an illusion, and immortalizing the subjects in the stone forever. One such artist was Michelangelo. Between the years 1498 to 1500, Michelangelo was commissioned and worked on his Roman Pietà, not the first of its kind, nor the last of his, as he later struggled over finishing another in Florence towards the end of his life. Serving as his first truly consequential sculpture in the eyes of patrons and the Church, the Pietà depicts the youthful Virgin Mary, cradling her lifeless son after his removal from the cross. Blending the ideal human form of the Classical Greeks with the dominant religion of the region: Catholicism, the Pietà stands as a paragon of the Humanist Italian values of dignity, intellect and the greatness of Man during the Renaissance. Michelangelo created greatness, not out of experience and training, at least not at first, but with sheer natural born talent.

Southern Europe’s Renaissance, specifically in Italy, was not led by the idealism of the Classical Age and an education of that past, in an attempt to reconnect with both the country’s Roman ancestry and the history of the next-door Greeks. It then fell upon the Catholic Church and royalty across the Italian peninsula to dictate the way art could be presented and expressed by an artist. According to author Bruce Cole of The Renaissance Artist at Work, “Around these men [Italian princes and the Pope], courts sprang up that attracted artists and writers,” like Dante and Michelangelo, “who worked often worked on projects to glorify the [patron]” (Cole 3). This practice of royal and Papal courts took away the necessity for an artist to glorify a faith, so long as the patron was sufficiently satisfied. Patronage and religious zeal were often intertwined during the Renaissance, with the Church being the largest patron for artists. Michelangelo’s Roman Pietà, in fact, was actually commissioned for the French Cardinal Lagraulas’ tomb chapel, as pietàs were the common funerary decoration in France. Perhaps not completely related to patronage or artistic age, the statue is also heavy in symbolism, though not as apparent to a modern audience who would lack the social and cultural context of such symbols.

Contemporary audiences are more detached form the time of the Renaissance then they often realize. Onlookers re unaware of symbols and references that would have been immediately obvious to a Renaissance age one. People before the Enlightenment and beyond were less acquainted with what the modern world considers secular rational thought, believing the Devil to be lurking behind every corner and that symbols around them had omens, good or bad. While a modern audience may have its own superstitions, they pale in comparison to how deeply a Renaissance audience was affected by them. “In an age that understood but did not fully trust the written word, a picture of the Madonna, the coat of arms of a noble family, or the emblem of a saint carried with it a cargo of associative meanings” (Cole 10-11), therefore, making it much harder for the modern audience to appreciate the images in a similar way. Cole also continued to say that “we have to constantly remind ourselves that every image made by the Renaissance artist was seen through the powerful lens of its own time” (11). To restate Cole, as a contemporary audience, it is harder to interpret Renaissance art the exact way it was intended, in relation to who and when it was made for. Luckily for the modern audience, religious images, like the Pietà, can retain their symbolic value and meaning due to the implications behind the piece, explained through the given faith.

While cemented in place, movement of the figures of the Virgin and Christ cannot be considered dynamic, their movement is more akin to a film still. The scene depicted is the moment after Christ is taken down from the cross and allowed to lie in the lap of his mother, although, as art historian and critic Edward Lucie-Smith points out in his book The Face of Jesus, “there is, in fact no reference to this in scripture” (203). Michelangelo cannot be credited with starting this genre though, as pietà images were in existence during the 1300s in Germany (Lucie-Smith 203). Nonetheless, the idea of such a scene was popularized to modern audience’s by the marble Roman Pietà, thanks to Michelangelo. Moving away from the subjects, Paul Barolsky, an author and art history professor, commented on the illusion of Michelangelo’s craft. In his book Michelangelo and the Finger of God, the artist’s persona is explored, as well as how his works are also fictitious representations of their marble. His marble works, like the Pietà and Bacchus are “paradoxically a finished form of the non finito, since they are the illusion of stone that has been faceted by [Michelangelo] to resemble stone that has no be carved at all” (Barolsky 22-23). Truly, it is a much more long-winded explanation than necessary, but concise wording removes Barolsky’s own literary artistry and could risk losing the most important point: the work is an illusion of reality a top the illusion of carved stone that doesn’t look carved. In relation to the stone and its carving, the way the subjects are carved and how they flow with each other is another point to make note of.

The Virgin and Christ rhythmically complement each other in the Pietà, creating a natural fluidity and formal relationship. The figures are depicted in relation to each other, as opposed to being at odds, and this was a planned maneuver artfully performed by Michelangelo. In the art history textbook, A History of Western Art by Laurie Schneider Adams it is stated that Michelangelo “creates an emotional and formal bond between two figures who, though separated by death, will eventually be reunited as King and Queen of Heaven” (287-288), which heavily weighs into the faiths of both artist and patron. Another purposeful move on Michelangelo’s part was the magnitude of Mary’s figure and his lack of mutilation after dying as “most spectators do not notice that the Virgin, cradling a full-grown man of heroic proportions, has become a giantess to support his size and weight,” as Christ is more Herculean than cadaverous, and Mary is made bigger than life, as Christianity is impossible with her existing first(Lucie-Smith 203). This was not an uncommon convention for the Renaissance, but it was unconventional for the specific theme that is a Pietà, whether by Michelangelo or otherwise, as it’s not a typical Italian Renaissance theme. Pietàs are German and Gothic in origin, and were popular in France, and only became popularized after Michelangelo completed his Roman one. Michelangelo simply blended two different ages of art with the faith of his patron, as well as his own psychological state while creating it.

Suspended in time, and seemingly asleep, Jesus is cradled in his mother’s lap as she gazes at him in contemplation, which contrasts the conventional appearance of pietàs, since they are representations of Mary’s ultimate grief. This, of course, is by no fault of Mary, or anyone, but is the result of an artist not being familiar enough with a theme to deliver what was required of it. Not intimate with the theme of tomb Pietàs in France, Michelangelo used his commission to express his desire for such a mother as Mary, “the most profound and driving emotion in Michelangelo’s life was the early terror of maternal disappearances. This prompted a lifelong quest for the reconciliation of mother and son”, as he had been passed off to a wetnurse as an infant himself(Hilloowala & Oremland 91). This serves as an explanation as to why the Pietà doesn’t have the same mournful intimacy that the traditional French ones; Michelangelo was simply a young artist trying to do his job well enough to prove he was talented, all while not completely matching the credentials of the theme. It is important to restate that that does not discredit the statue as a proper tomb pietà, authors of “The St. Peter’s ‘Pietà’: A Madonna and Child? An Anatomical and Psychological Reevaluation” further cement this assertion by stating that “the theme of the Pietà had been chosen not by him but by the French Cardinal,” and that these types of statues had been a “national tradition in France since the end of the fourteenth century” (Hilloowala & Oremland 90). This tradition started after the original theme had been founded in Germany and spread to France, where it gained much more popularity, but never gained such in Italy. It can be concluded that while the Pietà is true to its name, it does not convey the gravity of somber emotions that it should, and this lack of appropriate emotion can be accredited to the young age of Michelangelo at the time of creating the piece and lack of worldly perspective.

The first Pietà of Michelangelo, still in Rome today and house in St. Peter’s Cathedral, stands as an anomaly both in theme and time. Previously belonging to the Gothic Age, it was reborn during the Renaissance, alongside the styles of Greek and Roman antiquity. Michelangelo brought to life a scene of death, with his own young mind influenced by the want of such a mother and cemented his own name amongst the greats of the Italian Renaissance. The Pietà is an artistic theme depicting the time after Christ had been removed from the cross, where his mother solemnly holds her firstborn son, the Messiah. This is not an idea or theme present in the scripture, and stems from the words of religious people interpreting the Crucifixion in a more human light. It sheds light on the relationship between mother and son, and though both knew Christ was destined to die, his mother is still grieving, unless she’s carved by Michelangelo, who made her contemplative. Both interpretations of Mary’s reaction to her son’s death could be accurate and true to the theme, as she would be grieving as a human mother, but contemplative as a Christian who knew her son would return and ascend into Heaven, where she would be with him again, forever. Form and emotion create the Pietà, and Michelangelo was the artist who could bring life to the stone that the two most important members of the Holy Family were encased in.

Works Cited:

Adams, Laurie. A History of Western Art, McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, 2011, pp. 287–288.

Barolsky, Paul. Michelangelo and the Finger of God. Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, 2003.

COLE, BRUCE. Renaissance Artist at Work: From Pisano to Titian. Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 1983.

Hilloowala, Rumy, and Jerome Oremland. “The St. Peter's ‘Pieta’: A Madonna and Child? an Anatomical and Psychological Reevaluation.” Leonardo, vol. 20, no. 1, 1987, pp. 87–92., https://doi.org/10.2307/1578217.

Lucie-Smith, Edward. The Face of Jesus. Abrams, 2011.

#michelangelo#renaissance#art history#bibliography#la pieta#christianity#catholic#college paper#art#rome

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

turning off your computer by clicking the digital shut down button = softly kissing it goodnight

turning off your computer by holding down the physical power button = strangling her to death

120K notes

·

View notes