Text

Two things have happened recently. I read Thomas Wartenberg’s Thinking on Screen, and I re-watched the first Lord of the Rings for the first time in a long while. There’s a lot to process in Wartenberg’s little book, but my experience with Lord of the Rings, or more precisely with its DVD box, seems to have attached itself to an early throw-away comment in the book, and I want to push that connection a bit.

Somewhere within his opening preamble, Wartenberg decides to get clear on some terminology. He talks about how we use the term ‘film’ rather loosely, referring as often to filmstock as to DVDs. He points out the distinction between these different incarnations of a film – projected in a theatre, aired on TV, viewed on some form of home video or digital file – only to collapse them all back into the term ‘film’ for simplicity’s sake (one term to rule them all). So, he tells us that what he really means when he says ‘film’ is ‘film and its cognate media.’ We can note how this formulation seems to privilege the film – itself a difficult thing to fully define – over its cognate media.

Now, I turn to my old extended edition DVD box set of the first Lord of the Rings movie. The ‘film’ itself opened in theatres smack dab on my 11th birthday, and my mom made damn sure we had tickets for opening night. I loved it, and I couldn’t wait for the next one. So, when I heard that an extended DVD edition was going to be released, I was thrilled. I got all three films in their box sets, and I used to put the bonus features on in the background while I did homework. Eventually I upgraded to a Blu-ray box set of all three films, but they weren’t the extended cuts, so I got a digital version of those onto a hard drive. But I always kept my DVD box sets, nostalgic as I am.

So, when Wartenberg takes things like DVDs to be copies of the film whose distinctness is trivial enough to be erased by simply expanding the meaning of the term ‘film,’ I pause for a moment and wonder if such cinematic appendages really are as trivial as all that. When I went to put on Lord of the Rings the other night (as a background film while I sorted through emails and made project timelines, some things haven’t changed), I chose to open up my old DVD box set instead of my hard drive. I doubt I had actually opened that box since my teens. It was a nostalgic process that affected my viewing of the film, making it somehow even more comfortable. And it had material effects too. The image quality was notably lower, and the sound mix was less dynamic. But I wanted that quality. It was the image/sound quality that I grew up with and that I remembered. That was the experience I was after.

One of the things I liked most about Wartenberg’s book was the emphasis on how we experience films. His argument for the philosophical significance of both The Matrix and The Third Man relied heavily on our experience of certain formal and narrative techniques. But I’m also interested in our experience with other aspects of film. Here, I think (perhaps too vaguely) of John Mullarkey’s comments about building a more expansive ontology of film, one that doesn’t simply capture the elements of a film but all of the elements that surround it too (things like viewing contexts, what we say/write about films, and so on). I start to wonder if our experience with film’s ‘cognate media’ might not have a more significant role to play in film-philosophy.

Wartenberg might agree with this shift in focus, but probably not in the way I’m imagining. For Wartenberg, films don’t have agency; they don’t ‘do’ things, even if he claims they can ‘do’ philosophy. In another terminological shell game, he really takes himself to be saying that filmmakers ‘do’ philosophy through their films. But I’m far less invested in authorial intent, and I’m more interested in exploring the power of objects to do things, something Daniel Frampton develops very nicely. And Lord of the Rings is the perfect film to have playing in the background while considering the power of objects.

5 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

“How often does a fish get a chance to eat some of the finer cheeses?”

I love how this thing just exists, for no apparent reason, like the rest of us.

0 notes

Photo

Untitled 1965-68 (Memphis Tennessee) - William Eggleston

I think about this woman’s hair constantly.

(On a more ‘serious’ note, I’m about to start Graham Harman’s introduction on speculative realism - especially excited for the chapter on objet oriented ontology - and Eggleston will be in the back of my mind the whole time)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’ve been wanting to read more film-philosophy this summer, especially articles. I want to feel out how this approach gets applied on a smaller and more concrete scale, close conversations with particular films or particular images. I find my ideas get lost in their generality and have a hard time coming back down to specific encounters with film. Reading the latest volume of Film-Philosophy, I seemed to hear an echo of this concern.

There are three featured articles, and the first two are heavy hitters: Jeff Fort’s essay attempts to re-read Bazin’s entire ontology (I’ve only read the abstract on this one, but it sounds very promising), and Jiri Anger develops an elegant account of ‘accidental aesthetics’ within the context of new digital technologies interacting with the materiality of filmstock. Both are grappling with film’s ontology, and both are trying to develop new ideas in relation to old traditions. Then, there’s the third article, by Silvia Angeli and Francesco Sticchi. At first glance, it seems far humbler in scope, simply applying concepts form the good old Deleuze/Guattari toolbox to a couple of European arthouse films. But there’s a germ of an idea nestled in this seemingly simple textual analysis, which might too easily be dismissed as a mere application of philosophical concepts to some films, and this idea interests me.

The idea has to do with how we experience a film, and, while it gets expressed succinctly at a few points within the article, it never seems to move to the foreground and become the point of what we’re reading. Textual analysis always occupies this centrality, and the notion of experience merely hovers around this analysis. Maybe the idea isn’t foregrounded because it’s been developed elsewhere, or maybe its significance is meant to be obvious. Whatever the reason, I want to foreground the idea for myself, if only to get a better grasp on it, to work through what it might mean for the film-philosophy relation.

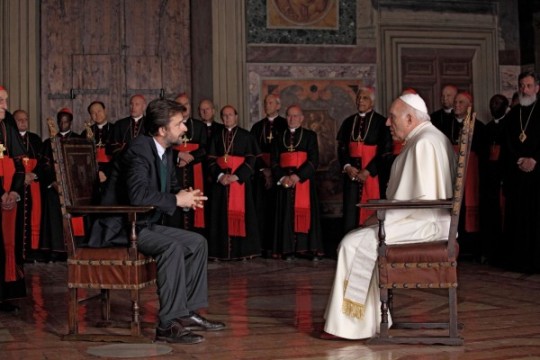

The article looks at two films with explicitly Christian themes, Moretti’s We Have a Pope and Rohrwacher’s exquisite debut Corpo Celeste. It applies the concept of a ‘line of flight’ to these two films in order to argue that each film ruptures with itself, opening up a line of flight that allows it to produce change and move in new directions. Because of each film’s theological themes, these lines of flight are seen as challenges to established traditions of understanding reality. So far so good. We have films that play with thematic preoccupations, and they seem to be leveling critiques or advancing a worldview. Good for them. But the idea of experience that the article wraps around this account seems to push these films past merely representing a pattern of thought. These films also provide viewers with the experience of these ideas, they “allow the audience to experience a major problematization of the institutions surrounding the two main characters” (4). This emphasis on experience seems to link the lines of flight that exist within each film’s formal construction with the viewer, putting that viewer through the very process of these lines of flight.

This idea might sound trivial, but it strikes me as a fundamental part of the film-philosophy relation. We experience films; they are objects of sensation that carry us through an (often-times) allotted unit of experience. This motivates some of my interest in the connections between viewership and ritual, but here I’m more interested in how this frames film as a specific kind of object, one that does things and takes us places.

At this point, my mind jumps to Sarah Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology, which I read recently and will doubtlessly misremember here. But what brings me back to this text is her interest in objects that can take us places, specifically ones that can pull us into new directions. She talks about how queer objects can manage such a pull. What makes these objects queer isn’t so much the objects themselves. Rather, it’s about our reaction to an encounter with these objects, which itself has to do with how we’re oriented toward them, and how this can give them a queer quality. Basically, a queer object is one that manages to pull us off the ‘straight line’ at the moment of encounter. In a simple sense, this is a process of estrangement, of suddenly noticing how everything we take for granted is in fact ordered in a specific way, rather than simply being given naturally. When something, an object, is out of place, we tend to rearrange it into place, to pull it in-line. But the out-of-place object also has the ability to reverse this process, pulling us off-line by making us suddenly aware of the strangeness within the order we intuitively maintain. Now, none of this sounds very queer, not yet. But, for Ahmed, these seemingly natural arrangements of objects in space are often constructed around heteronormative assumptions, which subtly reinforce the naturalness of such heteronormativity through arranging our bodies in particular ways around such objects.

As the title of her book evokes, Ahmed gets the notion of a ‘straight line’ from phenomenology, specifically Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception. This line actually starts out as an issue of perception, with Merleau-Ponty’s observations about how we tend to straighten our perception along a vertical axis in order to bring order to that perception. From there, Ahmed develops an entire analysis of how this process of alignment continues throughout other facets of experience. The family unit, with its basis in an assumed heterosexual line of procreation and continuance, structures much of this cultural alignment process. So, we’re in-line when we’re experiencing reality from the starting point of – and moving along the trajectory of – heteronormative reproduction. Anything that takes us off this trajectory, even for a moment, pulls us off-line.

Film can be such a queer object, without a doubt. I still remember noticing Steve McQueen’s ass, in pristine white pants, from The Sand Pebbles. That was a sudden encounter, somewhere in the nebulous mire of middle school, that could be said to have pulled me off-line, if only briefly. The pull of desire is just that, a pull. It opens up new trajectories, sometimes followed and sometimes not. However, this would be an account of film as a kind of brute queer object, something that evokes a sudden response to singular moment of encounter. But the way that films take us through an experience with their structure, as touched upon by Angeli and Sticchi, is more complex than this. It takes into account the formal properties of the film and, more importantly, how they interact to create a more prolonged experience. When I think of films that could be thought of as queer objects in this way, my mind turns to Claire Denis and Beau Travail.

The main conflict is between Galoup, a French Legionnaire of some mid-range stature, and one of his soldiers, Sentain. The nature of the conflict remains ambiguous throughout the entire film, but it’s interesting that Galoup feels this conflict immediately after his first encounter with Sentain. Sentain sticks out to him, and Galoup then talks about a ‘vague and menacing’ feeling that takes hold, which will drive his obsessive resistance to Sentain for the rest of film. But what’s really at the root of this feeling, so suddenly evoked? Given the way Denis films the sensual rhythms of male bodies, a homoerotic tension is clearly foregrounded, but there appears to be something more to it than that.

Ahmed’s notion of being pulled off-line comes with the complementary idea of being maintained on-line. She talks of ‘straightening devices’ that function somewhat in opposition to queer objects. Such devices work to keep us on the straight line by both maintaining our on-line position and erasing off-line alternatives. In Beau Travail, Galoup seems to take on the function of an ever-active straightening device. His role is to train the troops and keep them ready for combat. As such, he is constantly ordering and structuring their bodies according to his regiment. He leads them through single file runs across the deserts, and he makes sure the pleated lines of their uniforms are ironed to perfection. In one particularly intense scene, he leads his men in a push-up routine that repeatedly maintains their bodily alignment to a simple up/down momentum. So, Galoup literally keeps his men in line. While this process seems to serve a merely military function, the film works to infuse this military context with a constant sexual tension. This tension reimagines the military apparatus as a sexual one, and Galoup’s functional straightening begins to be seen in a different light.

Sentain’s arrival seems to pull Galoup off-line, creating the vague and menacing feeling. But instead of becoming a story about a man who can’t handle his homosexual desire, the film’s form makes it more of an investigation into the failure of the straightening process. Ahmed stresses that the process of maintaining straightness comes at a cost, the cost of systematic denial (some big and some small). Here, it’s helpful to remember that the film is told retrospectively, from Galoup’s memory. What’s interesting to me is how the film differs so much from the rigid linearity of Galoup as straightening device. Denis films male bodies from every angle imaginable, constantly adopting new orientations of vision that work to create potentially threatening positions. The film is always looking through new angles to see what might pull things off the straight line, while Galoup is fighting to maintain this very same line. It’s as if we’re seeing Galoup’s work in the state of orientational flux that Sentain’s pull of desire causes, a state that he distinctly remembers. This is the tension of the film, and it constantly works to pull us off-line, while producing a narrative about the failure of the straightening process.

youtube

So, along our initial lines, Beau Travail gives us an experience of being pulled off-line. This isn’t the kind of accidental experience that The Sand Pebbles gave me, but rather an experience designed into the form of the film. The question then becomes: what does this experience amount to? Is Beau Travail just a handy example of ideas articulated by Sarah Ahmed? It seems to me that focusing on experience takes the film in a different direction than this reduction. There’s a difference between reading and understanding the logic of Ahmed’s idea of being pulled off-line, on the one hand, and actually being pulled off-line, on the other hand. Beau Travail gives us the experience of Ahmed’s idea, rather than trying to articulate it. How significant is this observation? I’m not sure yet, but it does highlight one of film’s interesting philosophical capabilities. What I like is that it takes us away from ideas of ‘cinematic thought,’ pulling us instead toward an understanding of the thoughtfulness of cinematic experience.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Let’s start with some silence from my favourite weirdo. An interview with no questions, just a relentless gaze.

2 notes

·

View notes