What's old is new again: restoring and reassessing George Washington's "new room" at Mount Vernon--formerly known as the Large Dining Room.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Refurbishing and Reinterpreting the New Room

The New Room, 2014. Photograph by Gavin Ashworth.

In March of 2014, Mount Vernon opened the Mansion’s restored and refurbished New Room. A number of changes were made to the architecture, which deputy director for architecture Tom Reinhart wrote about here, as well as to the room’s furnishings. We had the opportunity to research many aspects of Washington’s “New Room” this year, but three topics form the foundation for our new interpretation:

the room’s 18th-century name

how George and Martha Washington used the room

furnishing the room as a picture gallery

“Distinguished by the Name of the New Room”

Visitors to Mount Vernon in recent years were introduced to the New Room as the “large dining room,” but from the room’s beginnings, it was referred to as the “New Room.” In the agreement for ornamental plasterwork for the room, executed in February 1786 by Tench Tilghman on Washington’s behalf, the room is referred to as “a Certain Room at Mount Vernon ... distinguished by the Name of the New Room.”

Of course, the room was unfinished in 1786, so it literally was the “New Room.” However, from the time of construction through the end of his life, the General consistently referred to the space as the “New Room.” A key word search the Washington papers online finds Washington making a total of 27 references to the “New Room,” often capitalized, as a proper name, between 1775 and 1797. Martha Washington also called this space the “new room” in her will, and the executors of both estates call it the “New Room” or the “large room.”

The “Banquet Hall” at Mount Vernon in a 1910 postcard.

Only in later years were more functional names applied, as subsequent generations struggled to make sense of this decidedly 18th-century space. From the 1880s until 1974, the preferred name for the room was the Banquet Hall, a name that evokes the grand houses, lavish entertaining, and ancestral pretensions of America’s late 19th-century elite. In 1981, the room received a new identity, officially re-christened the “Large Dining Room,” a term Washington used rarely.

In Samuel Vaughan’s 1787 presentation drawing of Mount Vernon, he labeled the New Room “Drawing Room 16 feet high.” Learn more about Vaughan’s drawing here.

We know from extensive surviving correspondence that Samuel Vaughan was a key source of information on English architecture and interiors as Washington was decorating Mount Vernon’s north wing in the mid-1780s. Vaughan personally supplied the marble mantel that became the room’s centerpiece, together with English porcelain garniture and a historical painting to ornament the chimney breast. Surely if Washington had intended this space for a dining room, Vaughan is the one person we can expect to have known this. Yet on his 1787 presentation drawing of Mount Vernon, Vaughan clearly labeled the space “Drawing Room” and also noted its unusual height.

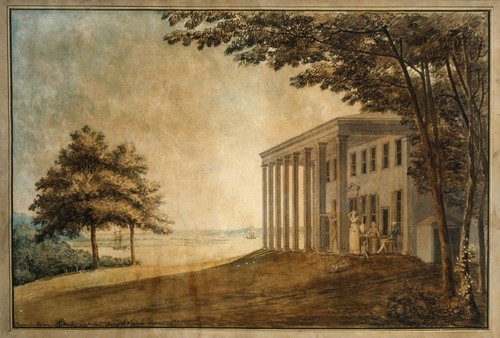

View of Mount Vernon with the Washington Family on the Piazza, drawn by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1796, ink and watercolor on paper. Purchased with funds provided in part by an anonymous donor, 2013 [W-5307]

Eighteenth-century visitors to Mount Vernon used a variety of terms for the Mansion’s north wing, suggesting a focus on its form, as well as a fluid, multi-purpose functionality. Samuel Powel of Philadelphia called the north wing simply “a magnificent Room”; Joshua Brookes, an English visitor, called it “the drawing room”; and Polish nobleman Julian Niemcewicz called it “a large salon.” Only English architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe called it “a good dining room,” and his professional training and familiarity with the recent fashion for adding large formal dining rooms onto English country houses may have colored his vision.

Room Use

Photograph by Renée Comet.

First and foremost, the north wing functioned as a necessary architectural element, maintaining the formal symmetry required of any self-respecting Georgian mansion house. From this standpoint, the New Room’s function was arguably secondary to its form; what mattered most was simply that Mount Vernon’s north wing existed, balancing the south wing (whose spaces answered the Washingtons’ practical needs for a more private bedchamber and study).

That being said, it is hard to imagine the eminently practical George Washington not putting such a large space to some purpose—be it practical, social, or symbolic.

The 18th-century saloon at Saltram House near Plymouth, England, was designed by Robert Adam circa 1768. It features green walls, a high coved ceiling, densely hung artwork, and a carved mantelpiece, which faces a Palladian window (not shown).

The New Room clearly served as a “show room” or statement room, in the tradition of grand saloons in 18th-century British country houses. A saloon was defined less by practical functions than by formal characteristics—notably great volume and height exceeding that of surrounding rooms and a strict adherence to symmetry—characteristics that combined to make these spaces feel out-of-the-ordinary.

The New Room seen from the door to the Little Parlor. Photograph by Gavin Ashworth.

Like saloons in grander English houses, the New Room could be pressed into service as a dining room when circumstances warranted, as when large numbers of guests or guests of high rank needed to be entertained. Analysis of Washington’s diaries between 1797 and 1799 suggests the Washingtons rarely had more than ten dinner guests, the number that would likely have fit comfortably in what we call the small dining room. Notably, George Washington’s 1799 probate inventory does not list any dining tables in the New Room; the only two dining tables listed in the Mansion are those located in the small dining room.

Symmetry on the New Room’s north wall. Photograph by Gavin Ashworth.

In line with the shift in interpretation from dining room to New Room, the new installation highlights the formal qualities of the space and its multi-purpose character. One of the most striking aspects of the inventory for this room is a strong sense of symmetry. Virtually every item has a counterpart—two large looking glasses, two sideboards, two candle stands, two pairs of John Trumbull’s Revolutionary War prints, two religious pictures, even two copies of a popular British print, The Dead Soldier.

The New Room as a Picture Gallery

In addition to highlighting that symmetry, the new installation showcases the room’s function as a picture gallery—a function echoing the furnishing of English saloons, and one certainly encouraged by the marvelous north light admitted by the Palladian window. The New Room’s function as a picture gallery is the room use for which we have the strongest and most concrete evidence—not only the documentary evidence of the inventory, but also physical evidence of the surviving works of art. Unlike dining equipment, the art works were there all of the time. If the room was sometimes a dining room, it was always a picture gallery, at least after the Washingtons returned from Philadelphia in March 1797.

Landscape paintings, religious pastels, and popular prints on the New Room’s south wall. Photograph by Gavin Ashworth.

The inventory lists a total of 21 pictures in this space—most in impressive and expensive gilt frames and all but two acquired by Washington after the beginning of his presidency. By the standards of the day, Washington’s art collection was an extraordinary one. With its seven large landscapes, it was effectively the earliest gallery of landscape paintings in America. Washington’s collection also gave prominent place to American subjects: the landscapes that celebrated the beauty, power, and potential of America’s natural resources, four engravings by John Trumbull that captured the dramatic moments in the United States’ war for independence, and a cabinet-style portrait of America’s first commander in chief, Washington at Verplanck’s Point by John Trumbull. For visitors to Mount Vernon in Washington’s day, the collection testified to Washington’s pride in the new nation and his hopes and dreams for its future.

With the New Room’s reopening, there are now twenty pictures on view, including at least seven of Washington’s original paintings, his two original pastels, and five of his original prints.

The New Room’s east wall. Photograph by Gavin Ashworth.

As visitors enter the room from the west door, they see the east wall, highlighted by a much denser display of framed artworks and new window treatments. The new arrangement of artwork is what is known as a “salon-style hang,” which means that artworks are hung floor-to-ceiling, often in vertical columns, creating a massed effect. Salon-style hangs were typical of installations in 18th-century English country houses, and are well documented in paintings and prints of the period.

For conservation reasons, several of the original Washington artworks will only be on view in the New Room through Memorial Day. For the present moment though, visitors can see the most accurate and comprehensive furnishing of the room since the Washingtons walked these floors. The recovered drama and beauty of the New Room helps us to understand what fueled the imaginations of the Washingtons and their guests, and to more fully appreciate his understanding of himself and his vision for America.

Susan P. Schoelwer, Robert H. Smith Senior Curator

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Architectural Restoration of the New Room: What Did We Learn?

Since the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association purchased Mount Vernon in 1858, the New Room has been restored about every 30 years, each time using new technology and methodologies to uncover physical evidence of the room’s appearance during Washington’s lifetime. This restoration, based on the cumulative research of 160 years, was no different. We made many discoveries that resulted in changes both subtle and striking to the room’s appearance.

The New Room’s south wall, before (above) and after (below) the restoration. Photographs by Walter Smalling, Jr.

The most immediately noticeable change is the new paint colors. These colors were selected after Dr. Susan Buck conducted careful microscopic analysis of the paint layers in room.

The restored ceiling and cove, newly whitewashed. Photograph by Walter Smalling, Jr.

Perhaps the most significant alteration is to the cove, which is now whitewashed to match the ceiling. Paint analysis conducted in 1980 had determined that the cove was green, but the current investigation could find no evidence of that color. Multiple paint samples taken from the original plaster on all four sides of the cove indicated that before 1869 the cove was always white. The overall effect is to visually associate the cove with the ceiling, rather than the walls, making the room seem taller and lighter.

Detail of the wooden molding, painted buff, and composition ornament, picked out with whitewash. Photograph by Walter Smalling, Jr.

We also found new evidence for the color that Washington called “buff inclining to white,” which is used on the wooden trim and wainscot. The linseed oil paint had sufficient yellow ochre pigment in it to result in a darker and tawnier color than previously thought. Paint analysis also indicated the composition ornament on the chair rail and friezes was whitewashed, and only the wooden elements of the trim were painted buff. The alternating use of buff and whitewash created a striped effect. The room’s friezes also received an updated color, a deep green made from the pigment verdigris.

Paint drying on rolls of wallpaper.

The vertical and horizontal seams in the wallpaper are much more subtle. Photograph by Walter Smalling, Jr.

Though we originally intended only to repaint the existing wallpaper, installed in the 1980s, consultation with our colleagues at Colonial Williamsburg prompted us to reexamine the paper and strive for a more authentic approach. The existing wallpaper had been installed sheet by sheet, creating a grid-like effect with visible seams. But by the time Washington purchased paper for the New Room, wallpaper was available in rolls created of sheets that were seamed together and painted before hanging. After examining comparable examples at Colonial Williamsburg, we decided to change course. Eleven-yard-long rolls of seamed sheets were hand painted at Mount Vernon using a green verditer paint before being hung in the room. The construction of the rolls before painting means the horizontal seams of wallpaper are less visible than the vertical ones.

Design from 18th-century pattern book in the Réveillon archive, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris.

Fragment of wallpaper found in the New Room (above) and Adelphi Paper Hanging’s new reproduction paper (below).

In addition to the green verditer paper, we also updated the wallpaper border that runs around the chair rail, doors, and windows. Fragments of the original border were first found in the room in 1902 and 1950, and reproductions were made for two restorations in the 20th century. As it turns out, the fragments found in the New Room were incomplete, meaning the reproductions had been as well. In 2012, wallpaper curator Bernard Jacque identified the complete pattern in an 18th-century pattern book in the Réveillon archive at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. Thanks to this discovery, Adelphi Paper Hangings was able to reproduce the wallpaper border in its entirety.

Andy Compton grains the doors.

The New Room’s four doors were also grained, a technique popular in the 18th century to make inexpensive woods (in this case, pine) look like exotic, expensive mahogany or other highly figured varieties. Graining takes three layers of paint: a pale peach base coat, a coat of varnish and brown pigment, and a final coat of varnish. While second coat is wet, the painter “figures” the paint to imitate the grain of mahogany. The new graining on the New Room’s doors is consistent with the high level of artistry seen throughout the room.

The west wall of the New Room, before (above) and after (below) the restoration. Cleaning the floor removed a 20th-century varnish that was trapped beneath the visitor carpet. Photographs by Walter Smalling, Jr.

Finally, we investigated the history of the New Room’s floor. Though its appearance is humble compared to the rest of the stylish room, the floor offered one of our most exciting discoveries. Documentary records indicated that in 1787 Washington purchased 24’ long yellow pine planks to be installed in the New Room using dowels and a blind nailing technique, meaning no nails were visible. This was the most expensive way to install a floor in the 18th century. The fact that nails are clearly visible in the floor today led to the longtime assumption that the floor had been replaced.

Examination of the floorboards from the below revealed that the boards dated to the 18th century. The identification of old dowels, cut in half, together with an analysis of the visible nails and current floorboard length (most of which are 24’, some having been repaired) led to the conclusion that this was indeed Washington’s original floor. It likely was pulled up and reinstalled with the nails you see today sometime between 1795 and 1820. With newfound respect, the floor was cleaned to remove grime and remnants of old varnish. Following 18th-century practice, no new finish was applied.

The north wall of the New Room after the restoration. Photograph by Walter Smalling, Jr.

As a result of this yearlong project, we are confident that the New Room is as close to its appearance during George Washington’s lifetime as it has been since the general himself was in residence. Please come visit and take a look for yourself.

Thomas A. Reinhart, Deputy Director for Architecture

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hanging Around: Cornice Boards, Part 3

Catch up with our investigation into Mount Vernon’s cornice boards here and here.

One of the Mount Vernon cornice boards rediscovered in storage.

Once we determined that the cornice boards were original to the room, we needed to determine the best way of presenting the cornice boards in the New Room. Unfortunately, we had a little bit of a problem with the antique cornice boards—the tulip poplar board on the face of each piece had been heavily eaten by powder post beetles, and as a result, we could not put much stress on the originals.

Additionally, the cornice boards had been painted so many times that the details of the composition ornament were obscured by paint accumulation. Each layer of paint contains valuable information about the history of the piece, and we didn’t want to remove that information by removing the accumulated paint.

We came up with a compromise that allowed us to preserve the original artifact and to represent the cornice boards in the room. We decided that we would use the paint evidence provided by Dr. Susan Buck and reproduce the cornice boards as they would have appeared when Washington purchased them.

For the wooden frame, we asked Jeff Headley of Mack Headley & Sons to make reproductions of our cornice boards. He made our reproductions in a very similar manner to the way they had been made in the 18th century and used the same materials—yellow pine and tulip poplar. The only difference between the originals and the ones Jeff produced is that Jeff steamed three laminated (or glued together) pieces of poplar and bent them to conform to the front curvature, while on the original the piece was a single piece of wood carved out on the front and the back.

One of the original cornice board (bottom) and the two reproduction boards, in various states of completion. The dark areas on the original cornice board show where conservator Karl Knauer removed layers of paint so we could take a mold of the composition ornament.

The next step in the process was the decoration, which would be by far the most difficult and time consuming aspect of the project. Our collections conservator, Karl Knauer, removed the paint from a single swag, bow, and rosette on one of the original cornice boards, taking it back to the first layers of paint. He then placed an extremely thin barrier on top of the ornamentation to protect it, and cast silicone molds of the elements.

We took the reproduction cornice boards and the silicone molds to conservator Tom Snyder in Williamsburg for the application of the ornament. Tom cast the ornaments in composition, a combination of animal glue, linseed oil, and resin that is malleable when wet, but dries to form a hard surface. He applied these to the surface of the wooden cornices and then began to apply the decorative finish.

One of the original cornice boards (top) and the two reproduction boards after they were completed.

To prepare the wood for gilding, Tom first applied multiple layers of gesso to the visible surfaces of the cornice board. Gesso is a combination of animal glue, chalk, and white pigments that creates a smooth surface when applied to wood. The material can only be applied in very thin layers, so Tom needed to coat the surface multiple times to build up the finish. He then applied a bole, or red clay substance, and then gold leaf to the composition ornament and molding profiles and burnished the gilding to an appropriate shine. The result is magnificent and really compliments the architecture of the room.

The cornice boards in the New Room, ready for installation.

On ladders, architectural conservator Neale Nickels (left) and assistant curator Adam Erby (right) install the cornice board, while textile consultant Natalie Larson and preservation specialist Sarah Martin (in the foreground) hold the curtain, preventing it from becoming wrinkled.

But what about the curtains? We decided that while it is likely that the cornice boards made up at least some portion of the value of the window curtains, the textiles themselves accounted for the vast majority of the assessment. The most reliable account is contained in Martha Washington’s will, where she bequeathed the “white dimity curtains in the new room” to her grandson, George Washington Parke Custis. Cotton dimity is a lightweight, sheer white fabric with a ribbed pattern. It was an incredibly popular option for curtains, bed hangings, slipcovers, and fashionable clothing in the neoclassical period. As Mount Vernon was Martha Washington’s home and she would have had a clear voice in selecting fabric furnishings, we felt her word should be privileged over other contemporary accounts.

The New Room's curtains were inspired by those shown in plate LXI, "A Plan and Section of a Drawing Room," in Thomas Sheraton's The Cabinet-maker and Upholsterer's Drawing Book, first published in 1791. The third edition, published in 1802, is digitized here.

Throughout the process, historic textile specialist Natalie Larson has guided us to sources for materials, advised on the search for hardware evidence, and she even made the curtains for us. Her hard work has been one of the keys to the success of this project. We chose to use an appropriate and popular pattern found in Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet-maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book. Natalie made the curtains with cotton dimity from Context Weavers of England. The white dimity curtains match the slipcovers on the chairs in the room, creating an appropriate en suite appearance. We also had a green trim produced by Ellen Holt of Houston, based upon a popular 18th-century trim pattern.

Natalie Larson installs the curtains to the cornice boards.

Natalie Larson completes the curtain installation.

The cornice board and curtains as they appear in the New Room today. Photograph by Gavin Ashworth.

Adam T. Erby, Assistant Curator

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Even More “Exceedingly Handsome”: The Vaughan Vase Reunited

On December 15, 1994, archaeologists excavating in a test unit outside of the New Room door on the Mansion’s west front made an amazing discovery. This small soft-paste porcelain molded and overglaze gilt handle once retained a more prominent position on George Washington’s mantel as part of a group of vases gifted by Samuel Vaughan in 1786—or at least that was the hypothesis! The color of the paste, the decoration, and the size of the archaeological handle looked identical to the garniture on display above the fireplace in the New Room. The only way to test this hypothesis was to remove the reproduction handles and see if the archaeological find fit.

The handle discovered outside the New Room’s west door.

A drawing of the handle by Karen E. Price.

After two decades of research, careful examination, some debate, and lots of patience waiting for the reproduction handles to be removed, we are finally able to say with certainty that the archaeological handle fits back onto one of the smaller vases. Instead of putting the reproduction handle back on the vase, the decision was made to mend the archaeologically recovered handle back in its original location. This might be the first instance of an archaeologically-excavated artifact being mended back to a museum object—truly a unique project.

This is where patience paid off. In the past 20 years, major advances in technology have improved our ability to document objects. Though the conservation treatment is reversible (meaning we can remove the archaeological artifact if needed), we wanted to create an identical replica for the archaeological collection through 3D scanning and printing. We worked with Direct Dimensions to laser scan the archaeological handle and print a life-size, archivally-stable handle to hold the place of the original in the archaeological collection.

The handle being scanned.

Following the identification of the archaeological handle, the goal of the conservation treatment was to remove the misaligned and oversized replacement handles that had been applied in a much earlier restoration to the vase, probably in the 19th century or early 20th century.

The vase with its old reproduction handles. Garniture vase, Worcester Porcelain Manufactory, 1768-1770. Purchase, 1963 [W-972/A]

The degraded adhesive used to adhere the old replacement was tenacious, and had to be removed slowly by injecting appropriate organic solvents and careful mechanical cleaning with micro-tools. But the payoff was really satisfying—after a few days, the aged adhesive had loosened enough to allow the handles to be removed.

The vase after its reproduction handles were removed.

At this point, we could see that threaded brass rods were used to hold up the fabricated replacement handles. In the past, the restorer had filed down and drilled holes into the original ceramic of the vase in order to adhere these rods into place. These methods are very invasive and would no longer be used in a conservation treatment.

The original archaeological handle held in place.

With the replacement handles removed, we could finally see where the original archaeological handle was most likely to fit; although much of the original break edge on the vase was lost from the past restoration, the remaining extension from the base of the archaeological handle matched the conchoidal chip-loss on the vase section to the proper left side of the tigers. Even the decorative grooves of the ribbing along the concave curve matched!

The original handle adhered to the vase.

Following the 3D scanning by the archaeological team, the archaeological handle was adhered to the corresponding area on the vase.

Additionally, the archaeologists had a 3D print made of the handle in an inert material. Because the printed handle is an exact replica of the original, and therefore a better version than the reproductions mended to the vase years ago, we opted to replace the missing handle with a printed version. This replica handle was perfectly suited to be used as an accurate fill at the loss on the opposite side because the vase would clearly have been symmetrical.

The vase with both original handle (right) and the replica handle (left) attached.

The areas that comprised voids on the handles were filled with conservation materials to visually complete their profiles.

Karl inpaints the fill to match the glaze.

These fills were made of partially translucent materials to mimic the effect of the porcelain. Finally, these fills were inpainted to match the subtle glazes and gilding. Additionally, to make sure the archaeological origins of this handle are always know, the object’s number was applied in an “invisible” paint made up of acrylic medium dyed with fluorescein, so it can be easily seen with an ultraviolet source. A miniature note about the handle was printed on acid-free paper and incorporated into the fill as well.

After the treatment was complete, we welcomed the vase, reunited with one handle and with a more accurate representation of the other, back into the New Room where it is now on display on the mantel.

The vase on the mantelpiece in the New Room. Photograph by Gavin Ashworth.

Eleanor Breen, Deputy Director for Archaeology, and Karl Knauer, Collections Conservator

0 notes

Photo

It's opening day for George Washington's New Room! We'll share more about wrapping up the project in the coming weeks, but for now, check out more photos of the fully restored room here.

Whether you visit in person or virtually, let us know what you think!

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Among the many pieces of the puzzle that fell into place this week was the arrival and installation of the reproduction Chinese grass matting, to represent the “East India Mat” described as being in the room in 1799.

Working with our talented team of conservators and Prism Carpets of Timonium, Maryland, we developed a modular covering, enabling us to setup the room as it might have appeared in Washington’s day (shown in the first image), with the matting covering the whole floor, or alternately, to remove sections to accommodate a more durable carpeting path for the visitors (the setup we will use on a daily basis).

To protect the original floors and prevent slippage of the matting (or collections personnel who may need to walk across it!), our conservator (and resident genius) Karl Knauer created a non-skid under-layer by applying silicone to polyester felt. Stable, inert, non-invasive and historically accurate in outward appearance -- it’s a satisfying solution.

Amanda Isaac, Associate Curator

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Interview with Walter Smalling, Architectural Photographer

Throughout the year, we’re featuring the many folks involved in the New Room’s restoration and their roles in the project. Today, we interview Walter Smalling, architectural photographer.

Greetings, Walter! Thank you for agreeing to be interviewed. Tell me about your job and your role in the New Room project.

I am an architectural photographer specializing in historic preservation. For ten years I was the photographer for the National Park Service and the National Register of Historic Places. I had also been assigned as a photographer to the Historic American Buildings Survey, known as HABS.

Walter Smalling sets up his camera to photograph the mantel in the New Room. Photograph by Karen Price.

It is in part because of this background that I am involved with the New Room project. I am photographically documenting the restoration, both before and after the work is completed, and both digitally and with good, old fashioned 4x5 black and white film.

It’s not unlike the way Matthew Brady worked in the 1860s. There is a wonderful symmetry, don’t you think, to photographing an historic building like Mount Vernon not only with the latest digital equipment, but also with a camera that has not really changed much in a century and a half!

Walter took this photograph in January of 2013, before any restoration work had occurred.

I think some people might be surprised to hear that you use black and white film as well as digital—why do you use it?

Mount Vernon has never been recorded for the HABS files at the Library of Congress and that is why we are doing the black and white photos.

The process of doing a HABS documentation is very thorough and lengthy. The HABS division of the Park Service was started as a make-work Farm Security Administration project for out-of-work architects during the Depression. It was a way of recording the architectural patrimony of the United States and having a record of any buildings that could someday be destroyed.

A building is drawn, photographed and described in words. My part is the photography. The idea is that the clarity of the large format negatives permits someone in the future to be able to count bricks or to replicate architectural details exactly. Also, as technology changes, it may be difficult or impossible to open digital files but these negatives can be held up to the sun and viewed!

Walter (right) is behind a black and white film camera while his assistant, Jason (left), is assessing the exposure with digital color SLR camera. The cloth over Walter’s head blocks light and makes it easier to through the viewfinder. Photograph by Karen Price.

What else have you been working on lately?

I am always working on a couple of books at any given time. At present I am under contract to do two books for the Italian publisher Rizzoli. But my first love really is this “old camera” large format photography.

What is your professional background and how did you get interested in doing this kind of work?

I got my start with the National Park Service, but I have spent a career working with architects, writers, preservationists, architectural historians, magazine editors, book publishers, museum staffs and the Library of Congress; I’ve been the photographer for about fifteen books, most of them on architecture and historic preservation. The books have ranged from Shaker architecture to the tea trade, from a couple of cookbooks to the White House complex, from architecture of America’s college campuses to farms of Virginia. I try to vary what I do to keep it interesting and fresh.

Walter in the New Room. Photograph by Karen Price.

I was starting my career in photography when a friend who was the director of a historic preservation society in Florida asked me to photograph an endangered building there. Alas, the building was torn down eventually, but I was hooked and old buildings have excited me ever since.

Walter took this photograph in February of 2014, when all the architectural restoration work was complete.

How does the New Room compare to some of the other historic interiors you have photographed?

Without question, it is one of a handful of the most beautiful rooms in America, as well as, of course, being one of the most important historically. The perfect proportions are immediately apparent and very satisfying. One is very aware of the personality of the man who built it. The restoration has been truly stunning; it has been a real privilege for me to be there as part of that team. Every craftsman I think likes working on a project where everything has been done right. It’s very satisfying.

Thank you, Walter!

Interview conducted and edited by Hannah Freece, Project Manager

0 notes

Note

So is the cove in the New Room Staying White?

The cove in the New Room will indeed remain white. This is based on the physical evidence found during paint analysis in 2012.

In 1979, the first paint analysis done in the room determined that the cove was green, and so for the last 30+ years it has been so. But in 2012, the paint analysis found no evidence for green paint on the cove prior to the 1980 paint. Multiple samples were taken on all four walls and the results were identical.

The paint history indicates that the cove was whitewashed in the 18th century and remained white for decades. The first layer of paint found on top of the whitewash was gray. Documentary evidence records that the Ladies painted the cove gray in 1868, so between 1787 and 1868 the cove was white. We are not sure where the green color came from in the 1979 analysis, but we are sure we have it right this time.

Thomas A. Reinhart, Deputy Director for Architecture

0 notes

Text

The Dead Soldier in the New Room

The Dead Soldier, engraved by James Heath after Joseph Wright, 1797. Purchase, 1936 [M-93/EE-2]

Just ask anyone who has tried to make sense of a chaotic gift table in the aftermath of a wedding or birthday party—problems arise when a present gets separated from its card. George Washington encountered this frustrating scenario in April of 1798, when a case containing a pair of prints arrived at Mount Vernon with no accompanying note.

It was not until July that Washington finally received a letter from Henry Philips, a Philadelphia merchant, explaining that the two prints were a gift from his brother. Francis Philips, who lived in England, had met Washington in Philadelphia two years prior. After returning home, he decided to send the prints to Washington, via his brother, as a token of his admiration. “I sent it [the case with the prints] about two months ago to Your address by one of the Packets bound to Alexandria,” Henry Philips wrote, “but the letter intended to accompany it was I find, too late for the vessel” (Henry Philips to George Washington, June 24, 1798).

Washington’s response conveys his satisfaction at having cleared up a mystery that likely vexed a man who valued order and etiquette: “I have been favoured with your obliging letter,” he wrote, “explaining a matter which before the receipt of it, was to me, an enigma” (George Washington to Henry Philips, July 8, 1798). Having opened the case to find “two elegant Prints… unaccompanied by a letter,” Washington suspected that they might have been delivered by mistake and considered returning them, except that the package also lacked a return address. Gratified to learn of the prints’ origin, Washington thanked Philips for his and his brother’s generosity and proceeded to hang the engravings in the New Room, where they appear in the 1799 inventory of Mount Vernon.

The prints contained in Philips’s package were two copies (one of which was a proof, or an impression taken before the printing plate was finished) of an English print entitled The Dead Soldier, engraved by James Heath and published in May of 1797. The source for the print was an oil painting by Joseph Wright of Derby, which had been exhibited to much acclaim at the Royal Academy in London in 1789. Wright’s painting was held in private hands for many years and is now in the collection of the University of Michigan Museums of Art and Archaeology.

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797), The Dead Soldier, Oil on canvas. The University of Museum Museums of Art and Archaeology 2006/1.156.

The painting (and by extension Heath’s engraving) depicts a woman cradling an infant and mourning the death of her husband, whose body lies beside her. The only visible face in the scene belongs to the child, who has fallen away from his mother’s breast in a portentous symbol of the family’s future poverty.

Detail of The Dead Soldier.

Much of the artwork in the New Room came back with Washington from Philadelphia and represented the retired president’s deliberate vision for the grandest space in the house. While these two prints arrived in a more unexpected fashion, Washington clearly saw a place for them in the design scheme of the room. Perhaps he was just being polite or needed something to fill space on the walls. Given how intentional Washington’s other choices were, however, it seems more likely that he found the poignant scene to be a sobering representation of the costs of war, a fitting counterpart to the dramatic battlefield deaths depicted in John Trumbull’s Revolutionary War prints.

Washington’s original copies of The Dead Soldier have not been located, but two period impressions of the print will be displayed in the New Room when it reopens.

Jessie MacLeod, Assistant Curator

0 notes

Text

An Interview with the Installation Team

Throughout the year, we’re featuring the many folks involved in the New Room’s restoration and their roles in the project. Today, we interview Elizabeth Chambers, Mount Vernon's director of exhibitions and collections management, and Bruce Lee, president of ELY, Inc.

Hello, Elizabeth and Bruce! Thank you for agreeing to be interviewed. Let’s start by telling me about your jobs.

Elizabeth Chambers (EC): I am the director of exhibitions and collections management at Mount Vernon. I manage the fine and decorative arts collection, which includes ensuring proper documentation for gifts and loans and maintaining proper storage for the artifacts. I also oversee the exhibition program in the Donald W. Reynolds Museum and Education Center as well as objects on display in the Mansion and outbuildings.

Bruce Lee: (BL) I am the president and a project manager at ELY, Inc., a museum services company.

What have your roles been in the New Room project?

EC: My role is to coordinate the deinstallation and then reinstallation of all the fine and decorative art objects in the room. I also coordinated the logistics of all the movement of objects in the interim, between conservators, storage, and the like.

BL: We design, fabricate, and install the mounts for the 3D objects, as well as attach the cleats and install the framed objects and mirrors.

What is a mount?

BL: A mount is a bracket that safely holds a museum artifact where it’s being displayed. It’s a display armature that protects the piece from falling or movement or theft. But also it needs to be invisible. Or that’s the request! You can’t make it invisible. It needs to be as unobtrusive as possible, yet secure.

Bruce Lee holds the custom mount ELY, Inc., fabricated for one of the mirrors in the New Room. The prongs he is pointing to will serve as the mount for the candelabra that rests on the bracket.

David Schlaegel and Bruce Lee install the mirror and bracket on their mount.

Once installed, the mount is nearly invisible. Read more about this mirror here.

You just completed the installation of all the hanging pieces in the room. What were some of the challenging aspects of accomplishing that?

EC: I would say the most challenging aspect was not knowing what was in the walls and what we were attaching the artwork to. We have pieces that are quite heavy and large and we have to make sure that they stay on the walls. Bruce bought a boroscope to help us with this.

What is a boroscope?

BL: It’s a little camera-like probe that you can stick into a hole in the wall and see if there are places where you can anchor, studs, or lath, or whatever’s in there. Then you’re not willy-nilly putting holes in 18th-century plaster. We’re trying to be as noninvasive as possible in the attachments to the building, but yet, as secure as possible.

Tom Reinhart, deputy director for architecture, and Neale Nickels, architectural conservator, use the boroscope to investigate inside the New Room’s walls.

EC: We worked with our preservation colleagues in a team effort to collaborate and find the best possible, least intrusive, most secure way to hang everything.

BL: And we also coordinate with the curators. It’s one thing to say we need to put the vases up here on the mantel, but you have to consider where exactly you want them. That changes how the mount works and what kind of mount you use. When you’re hanging the paintings, even if we have the drawings and dimensions in advance, when you see it on the wall you might look at it differently. You have to adjust, and in an 18th-century building you can’t throw all these holes in the wall every time.

EC: You can’t just spackle it.

BL: It’s not like working in a gallery where you could hang something, and then take it down and hang it five inches to the left. You don’t have that option.

Dermot Rooney and Bruce Lee hang William Winstanley’s Morning on its cleats in the New Room.

Elizabeth, you oversee installation of exhibitions here at Mount Vernon’s museum, and Bruce, you have experience installing artwork in many other museums. Would you say that dealing with the wall structure is the main consideration that makes this different, to be in a historic house rather than a museum?

BL: Right, a museum is designed for exactly that purpose, hanging stuff on walls. Usually there’s structure back behind the sheet rock or plaster that you can attach to, and usually you know where it all is and what you can do. Here, you don’t know that. So, for instance, the 180-pound mirror needs a substantial amount of support, but because of the nature of the building, minimal anchors and holes. We have to balance the two and make sure that the mirror doesn’t come crashing down.

Sarah Martin (left), preservation specialist, and Elizabeth Chambers (right) discuss the installation plan.

How did you get interested in museum work?

EC: I was a history major with no idea about what I wanted to do. I did an internship in museums and worked my way into collections management. I started working as exhibitions registrar at Mount Vernon, before eventually becoming collections manager, and now, director of exhibitions and collections management.

BL: I studied painting and worked construction to put myself through school. I had a construction background and I understood how paintings are structured and how they work, and that kind of happened because I needed to eat—I got a job working for art handling companies and museums and doing installations.

What are you most excited about for the New Room project?

EC: I am most excited to see the different interpretation of the room. It’s always been a dining room as long as I’ve been at Mount Vernon, and to see it more as a salon-style room I think is very exciting. And I don’t have to worry about the security of all the china on the table!

BL: I’m most excited about meeting all the folks who have worked on it, preservation folks, faux finishers, and all those guys. It’s amazing, the skills and trades that work here to do all this. Karl is fantastic. These people are really skilled and it’s a pleasure to be working with them.

Thank you both!

Interview conducted and edited by Hannah Freece, Project Manager

0 notes

Video

vimeo

Assistant curator Adam Erby describes the history and design of the decorative marble mantelpiece that sits at the heart of the New Room, a gift to Washington from Samuel Vaughan.

0 notes

Text

Graining the New Room's doors

The finishing touches to the architectural phase of the New Room are under way. Conservator Andy Compton is hard at work graining the pine doors to give them the appearance of mahogany. This technique of applying a faux finish to inexpensive woods to give them the appearance of costly exotic woods was very popular in the 18th century. Andy is using the same multi-step technique that was used in Washington’s day.

First, a light-toned ground coat, in this case a peachy color, is applied. Then the painstaking process of applying the faux graining begins. Andy starts by painting the door with a glaze made of varnish, linseed oil and red-brown pigments. The surface of the glaze layer is then worked or “flogged” with special brushes until it is “figured” to approximate the appearance of the desired wood. Finally, several layers of varnish are applied to preserve the surface.

After his return to Mount Vernon at the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, Washington embarked on a major campaign of repainting in the house. Starting in 1786, he seems to have adopted graining as a particularly favored method of surface embellishment. In that year Washington had the woodwork in his study, including a new glass-fronted press built to hold his 900-book library, grained to approximate the appearance of walnut. In 1797, he had the paneling and all other woodwork in the central passage and the upper hall and the doors on the first floor grained to resemble mahogany. It is not known for certain which paint campaign accounts for the graining of the New Room, but in either case Andy’s talents are bringing this eye-catching part of the room’s finish back to life.

Thomas A. Reinhart, Deputy Director for Architecture

0 notes

Text

An Interview with Jessie MacLeod, Assistant Curator

Throughout the year, we’re featuring the many folks involved in the New Room’s restoration and their roles in the project. Today, we interview Jessie MacLeod, Assistant Curator.

Hello, Jessie! Thanks for agreeing to be interviewed. Tell me about your job at Mount Vernon and your role in the New Room project.

I am an assistant curator, so my job is to research and care for our collection of fine and decorative arts and work on exhibitions in the museum. In the New Room project I’ve been responsible for researching the prints and pastels as well as developing the hanging plan for where we’re going to hang the artwork on the walls. I’ve also been working on researching the bisque porcelain figures that Washington displayed in the room and acquiring period pieces that are similar to the ones he had.

A mockup demonstrating how artwork might be hung on the east wall of the New Room. Paper cutouts represent the works of art.

Most recently we finalized the hanging plan, which we came up with by looking at examples of interiors in paintings and other print sources to see how Washington’s contemporaries were hanging their artwork and what the style was at the time.

Is that because we don’t know how he hung is artwork?

Yes. We have wonderful documentation about what those items were, but most of them are listed in the inventory by type, so you have two landscape paintings, two prints of the Dead Soldier, that kind of thing.

So that doesn’t necessarily tell you where they were.

Exactly. We don’t know how Washington arranged his artwork, so we have been looking at other period examples. We also haven’t previously displayed all of the artwork that’s in the inventory on the walls of the New Room. Now, for the first time, we will have nearly everything.

One interesting thing that Washington did is display two copies each of three different prints. That increases the amount of artwork that we previously had. We had two of the Dead Soldier print before, but we only had one of each Trumbull and now we’ll have two of each. We’ll also have two pastels whereas before we only had the Virgin Mary. We’re adding in the four small prints which previously we had not even identified.

There’s a greater volume of artwork that will hang on the walls, and that will require us to think creatively about where we hang things. It is also going to make the walls look denser and give the room more of a salon or gallery-style feel. Washington probably would have been influenced by country houses in England, at least peripherally, even though he never saw them himself. We think he would have wanted the room to be a showcase for the artwork that he acquired, much of it while he was in Philadelphia. It’s been something of a challenge to arrange the artwork because certain things can only fit in certain spots because of how big they are. It’s a bit like solving a puzzle. And there are other considerations like not having important pieces in places where they’re vulnerable because of doors opening or people walking close by. Those are practical considerations.

Another mockup, this time made using paper maquettes, of artwork on the east wall.

We have to take into consideration things that Washington may not have had to take into consideration.

Yes, because we are both replicating his design and vision and functioning as a museum that welcomes a million visitors a year. He did have a lot of visitors, but not that many!

One challenge that we’ve had is that symmetry was really important in salon-style hangs, but the walls in the New Room are not symmetrical. The east and west walls are not symmetrical because of the windows and doors. As we’ve been putting this together, people have had reactions that it looks kind of weird. But even though Washington was perhaps aspiring to an ideal aesthetic, he would have had to make concessions to the architecture and physical space available to him in his own room.

This digital mockup shows a third potential arrangement for the artwork. Come visit the New Room when it is open to see what arrangement we selected!

That reminds me of the west façade of the house. You can see that the desire was for the house to appear symmetrical, but the front door is slightly off center. Symmetry was the aspiration.

Yes. We’re functioning within the same constraints that Washington did, which is an interesting way to put yourself in his shoes. It’s times like these when you wish you could know what was going on in his head.

Tell me about your discovery about Washington’s “four small prints.”

On the inventory of the New Room, most of the artwork is identified by name and because those things have been preserved very well we’ve been able to identify if not the original, at least what the item was. There’s one somewhat cryptic listing that just says “four small prints” and I was tasked with trying to identify them.

I was able to determine a probable identity for them by looking at Washington’s lists of prints from when he returned from Philadelphia. He brought a number of items, including prints, back with him and he listed their dimensions. There are four listed that are smaller than all the rest. Two of those on his list don’t have names, but by looking at some price lists from print sellers at the time I was able to find some prints that match the dimensions and for a few other reasons seem to be likely candidates for the prints that he ordered.

One of Washington's "four small prints," Urania, engraved by William Wynne Ryland, after Giovanni Battista Cipriani, 1784. [M-5328]

For the first time, when we reopen the room we will be interpreting those prints and fully realizing the inventory in a way that we haven’t done before, and that’s exciting. We’ll have everything listed except for the one unidentified painting. We’re leaving an open spot on the wall for it in case it ever turns up!

What are some of your other projects at Mount Vernon?

The main thing that I’m starting to delve into is our next exhibition which will open after Gardens & Groves closes in 2016. We’ll be doing an exhibition on slavery at Mount Vernon, looking at the lives and identities of the enslaved people who lived and worked here. A lot of research has already been done, so I’m building on that and doing some additional research in order to come up with the best possible way to interpret this important story to our visitors.

Have you found any connections between your research on the New Room and your research on slavery?

Actually, researching slavery has made me to think about the New Room differently. Although it was the grandest room in the house and a showpiece for Washington to display all of his artwork to his visitors, that space would have been occupied at various times by the enslaved people who worked there. They would have been there first thing in the morning to light a fire in the stove, they would have dusted the bisque porcelain figures, which as we have learned attract dust really quickly. They would have lit the candles and the Argand lamps when the Washingtons were entertaining in the room. When the Washingtons had large dinner parties, late at night, they would have cleaned up. They would have been the ones to move the table from the small dining room into the New Room when there were lots of people to entertain. Just like every room in the house, the New Room was also a site of slavery and labor, which is often obscured by the grandeur that we tend to associate with it.

Some of our most useful records of the New Room come from visitors’ accounts, and they might not have seen any or most of that work going on.

Right. Although interestingly, some of those same visitors who have really great descriptions of the New Room also have great descriptions of slavery. They wouldn’t have seen the work that went on in the house because that would have been deliberately behind the scenes. But those outsiders are often our best resource for observations on the slave quarters, for example, or what enslaved people were doing. For some of them, especially foreigners like Julian Ursyn Niemcewiz, who was Polish, slavery was an unfamiliar concept and they tended to take note of things that Americans did not.

How did you get interested in museum work?

I have always been interested in history and I went to lots of museums with my family growing up. I have very fond memories of visiting Old Sturbridge Village, Plimoth Plantation, Mystic Seaport and sites like that when I was a child. As an undergraduate, I was a history major and I stumbled into a summer job at the Yale University Art Gallery cataloguing Rhode Island furniture. I had no idea that people actually studied things like that! But I became intrigued and spending the entire summer cataloguing things like cabriole legs and ball-and-claw feet made me interested in the people who actually purchased and used and sat in these types of pieces of furniture.

After that, I took some classes in material culture and decorative arts and became more interested in that world. I did some internships at museums and decided it was something I wanted to pursue. After graduating I got a couple of temporary jobs in museums and historic sites and eventually decided to go to graduate school at the University of Massachusetts Amherst to get my master’s degree in history with a certificate in public history. It allowed me to pursue history academically but also study the theory and practice of public history. Public history addresses how we interpret history to various audiences, not just academics, and how you can best work for and with your audiences to tell important stories about the past. My background is a bit different from some of the other curators here, but I think that has been advantageous because I have a different perspective and different sorts of experiences. I started working at Mount Vernon after I got my master’s degree.

Jessie MacLeod oversees photography of The Battle at Bunker's Hill near Boston the June 17th, 1775, engraved by Johann Gotthard von Muller after John Trumbull, 1798, before it goes on view in the New Room.

What do you think is unique about the New Room?

One thing that’s been wonderful and makes the New Room and Mount Vernon unique is how well documented it is. Before going to graduate school I worked at Montpelier, James Madison’s home, while they were undergoing a refurnishing project. The challenges we faced there were very different because there is no inventory and there’s much less documentation about what the Madisons were purchasing. We had to speculate a lot more. For the New Room, we have so much written documentation and so many of the original objects that survive. We’re able to replicate the room with a level of accuracy that many sites are not able to do. Of course, having a lot of documentation presents its own problems because sometimes you have conflicting accounts or you don’t know how to interpret something. It’s not always a blessing. But on the whole we’re very lucky that to have so much information about the room.

What are you most excited about for the restoration?

I am most excited about shifting the interpretation from that of the “large dining room” to that of a salon or gallery. As part of that, I am looking forward to seeing how the room looks with all of the artwork, or nearly all of it, interpreted. The walls are going to be much denser and it’s going to have a very different feel. Previously the table was the centerpiece and people would ooh and ahh over the porcelain and the centerpieces, and now the focal point will be all around you. Our visitors will have similar experiences to those that Washington’s visitors had, which is walking in and being awed by the sheer volume and beauty of the artwork and the architecture.

Thanks, Jessie!

Interview conducted and edited by Hannah Freece, Project Manager

0 notes

Text

An Interview with Derick Tickle, Decorative Restoration Artist

Throughout the year, we’re featuring the many folks involved in the New Room’s restoration and their roles in the project. Today, we interview Derick Tickle, Decorative Restoration Artist.

Hello, Derick! Thank you for participating in this interview. Let’s start with your work. Tell me a little about what you do.

I’m a decorative restoration artist, which really means that I do architectural restoration: marbleizing, wood graining, wallpaper, and anything which is decorative and needs restoring.

What are you working on in the New Room?

I was asked to hang the wallpaper in the room. After I’ve hung the wallpaper, which will go along the wall above the chair rail, I will install the border as well.

So far, we have hung the lining paper, which is traditionally hung horizontally. The finishing paper will go vertically and that’s so they get a good bond. The joints don’t coincide. The lining paper is a good quality wood paper. It’s very nice to work with, quite strong, and it gives a lot of strength to the wall by covering cracks in the plaster. It will actually help stabilize the surface.

Then we applied a sizing, traditionally it’s a rabbit’s skin glue size. The sizing stops the wheat paste adhesive from soaking into the lining paper too fast and preventing you from adjusting the paper. It makes it so that you can move the paper around without creases.

You don’t have to get the paper perfectly in the right place on the first try?

That’s right. You put it on where you think it should go and then you can move it around to get it lined up with a plumb line. It also stops the paper from drying too fast so that you can’t cut it properly. It makes it more manageable to trim.

The finishing paper is in rolls made up of rectangular sheets because in Washington’s time they couldn’t make long pieces of paper like today. The manufacturer attached these squares together to make a roll 11 yards long. The gluing process is called tipping, where they tip the joints with glue.

Does that mean they just adhere one edge over the other?

Yes. When we hang it, we overlap each piece on the vertical, and it looks like squares applied to the wall, but the horizontal lines don’t line up because you are hanging it in strips from the roll. That’s why you see these joints here. Normally I try to hide all my joints, but here we’re asked to let them show because that’s how they were done in the time.

Derick Tickle applies wallpaper in the New Room. The faint vertical lines are the joints where strips of tipped together square paper have been joined.

No, they don’t, and the reason for that is because the paper was painted after they were tipped together, but before the paper was hung. Now that I’m hanging them, there’s no paint to fill the vertical joints between the rolls. So you see the vertical joints, but not the others so much.

Will the appearance change over time?

Not really. With distemper, even the hybrid distemper that we’re using, you don’t see a lot of changes in color or texture. It’s flat and it’s not like some of the modern paints. If you get a flat vinyl paint eventually you’ll see a sheen here and there. Distemper is pretty consistent.

What we are a little concerned about is where people might touch. With this being a flat bondable surface, it can easily get finger marks. We’re trying to decide whether to use some kind of sealer in the areas where people are likely to touch, without it showing too much. That’s under investigation right now. Andy Compton is testing that.

Andy Compton (left) and Derick mixing wheat paste which they will use to adhere the paper to the wall.

Would you mind speaking a little about your background and how you got into restoration work?

I started doing this kind of work when I was 15 years old as an apprentice and that was in 1954, so you can do the calculations. When I left school I went straight into this trade as an apprentice in the north of England, just outside of Manchester. I was very fortunate, I worked with a company that employed a dozen craftsmen. They all had different skills: wallpapering, sign writing, marbleizing, wood graining and all that. We would be doing theaters and churches, residential houses and so on, so it was a whole gambit of types of restoration work.

I served my six years’ apprenticeship and then I started my own business when I was in my mid-twenties. I was really interested in teaching my skills and I did some part-time teaching at some technical colleges in England. Then I became a fulltime lecturer and examiner for a guild, the City & Guilds of London, which is a craft guild that examines carpentry, plumbing, ornamental plaster, painting, decorating, and all different crafts. I would travel around to colleges doing examination work.

In 1989, I went to New Zealand on a teacher exchange and taught there for a year. When I got back to England, I was invited to come to America to start a program in Asheville, North Carolina, for the Biltmore House. Biltmore started the restoration program and I taught that program for sixteen years. Each year we would go into Biltmore House and restore one of the rooms to its original state. The students learned through that hands-on process. We would only do four or five weeks there each year because the program was a yearlong class, full time. We would do other projects as well but our main aim was to do the Biltmore restoration and then we would work in the lab doing other skills and practice work.

I retired ten years ago and thought I was going to go into retirement, but here I am in George Washington’s house! One of the reasons I did retire at my retirement age was that I wanted to be involved with the work onsite as long as I was able to. The last ten years have been great because I’ve been traveling around working on different projects and working with many of my former students.

Derick applies wheat paste to the back of the wallpaper before hanging it on the wall.

You’ve worked at Biltmore and other properties in England and America. How does the New Room and this restoration project compare?

The interesting thing about this project is that they’re using very authentic and original materials, even down to the wallpaper paste, which is traditional wheat paste. Painting the wallpaper in sections is not always the case. Normally it’s applied and then it’s painted afterwards.

But George Washington actually ordered pieces of painted paper. We’re doing something that was actually done at that time, very authentic, and not just a redecoration but a reproduction of what was there. That’s all of interest to me and the fact that everything I do, they want me to do in a very traditional way, even down to using scissors to cut the wallpaper and the border.

What would you normally use today?

Today I would use a straightedge and an X-Acto knife, which didn’t exist then. The thing is, when I was an apprentice in the 1950s, we didn’t have X-Acto knives either, we had utility knives, but we used scissors all the time. So some of the tools I’m using here, they’ve actually been with me all my life. That is interesting to me, that I can now use the tools that I thought I’d never use again.

It sounds like there is some similarity between the 18th century and the 1950s!

Well, there is. The main development over that period has been in materials, not equipment. When I started in the '50s in my apprenticeships, there weren’t even rollers, they didn’t exist. I remember going to a meeting where this German company was introducing rollers, and all the decorating trade just pooh-poohed them because they said oh, they’ll leave streaks on the wall—and they did at that time, they weren’t the quality that we get now.

The main advancement has been in materials like acrylics and resins and different types of paint, adhesives, all for speed. We live in a faster world, so everything is designed around doing it faster. It’s nice to be involved in a project where it’s a matter of getting it right rather than doing it in super time.

All of the techniques relate to the materials, so they all have to match up. That’s why I’ve been asked to use scissors and not a knife, because if you’re using traditional materials, it can look cheesy if you try to make them look too clean and slick and perfect. You have to have some handmade vision to it.

Thank you, Derick!

Interview conducted and edited by Hannah Freece, Project Manager

0 notes

Text

Furnishing the New Room: John Trumbull’s Prints of the American Revolution

When he toured Mount Vernon in 1798, Polish visitor Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz noted that among the New Room’s decorations were “a few pictures, engravings after Thrumbull [sic], representing the death of Gl. Warren and Gl. Montgomery.”

Niemcewicz was referring to prints after paintings by John Trumbull: The Battle of Bunker's Hill, June 17, 1775 (which portrayed the death of General Joseph Warren) and The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775.

John Trumbull, The Battle of Bunker's Hill, June 17, 1775, 1786. Yale University Art Gallery

John Trumbull, The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775, 1786. Yale University Art Gallery

Such engraving projects were typically funded through advance subscriptions from interested buyers. As a personal friend and supporter of Trumbull’s work, Washington eagerly subscribed to four copies of each print.

After traveling to England, the artist would encounter difficulty in finding engravers for his paintings, however, and the first version of the print—known as the “proof”—was not finished until 1798, eight years after the initial subscription was circulated (you can read more about proofs and printmaking terminology here).

In an apologetic letter of March 6, 1798, Trumbull wrote to Washington that he was sending from London “a pair of Proofs of these Prints, which I beg you will do me the Honour to accept.” These proofs, Trumbull wrote, along “with those for which you are a Subscriber…will form a complete Series of impressions, in the various Stages of the progress of this Work.” The remaining prints finally arrived at Mount Vernon in February of 1799, just ten months before Washington’s death.

The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775, engraved by Johan Frederick Clemens after John Trumbull, 1798. Purchased by the Connoisseurs’ Society of Mount Vernon, 2013 [W-5288]. One of Washington’s prints in its original frame and églomisé (reverse-painted glass). This print and frame are currently undergoing conservation and will be hung in the New Room for its reopening

And so, Washington ended up with five impressions of each of these two prints, each varying slightly due to the engravers’ last-minute changes to the printing plates. From the 1799 inventory, we know that Washington hung two of each print in the New Room—much of the room had already been furnished and decorated, but Washington clearly wanted to display these prints prominently—and an additional impression along the stairway in the Central Passage.

The Battle of Bunker's Hill, June 17, 1775, engraved by Johann Gotthard von Muller after John Trumbull, 1798. Purchased with funds provided by The Partiger Bequest, 2012 [W-5289]

It is rather unusual to hang so many duplicates—especially two in the same room. While we don’t know exactly why he chose to do this, it’s clear that Washington was keen to support Trumbull’s artistic endeavors. It is likely, too, that he found the prints’ subject matter to be a powerful representation of the sacrifices made by those who fought alongside him in the American Revolution.

Through loans and acquisitions, Mount Vernon is currently in possession of four of Washington’s original ten Trumbull prints, as well as several other period duplicates. Previously, only one of each print was hung in the New Room. When the room reopens, however, we plan to install all four original prints, thus replicating Washington’s hanging scheme—and the experience of visitors like Niemcewicz—more accurately.

Jessie MacLeod, Assistant Curator

1 note

·

View note

Text

An Interview with Karl Knauer, Collections Conservator

Throughout the year, we’re featuring the many folks involved in the New Room’s restoration and their roles in the project. Today, we interview Karl Knauer, Collections Conservator.

Hi Karl! Thank you for agreeing to be interviewed. What do you do at Mount Vernon, and what is your role in the New Room project?

I’m the collections conservator in the Historic Preservation and Collections department here at Mount Vernon. My role in the New Room project is to coordinate a lot of the conservation work that’s being done on the objects that will go into the New Room when the restoration is complete. That includes static, stationary objects like the mantelpiece and the grate, but there are a lot of smaller, moveable objects like paintings, works on paper, several prints, two pastels, a variety of silver objects, furniture, and things like that. I’ve been coordinating the work with specialists in various aspects of conservation or media: paper conservators, frame conservators, paintings conservators, and other object conservators like myself.

Tell me a little bit about what you do as the collections conservator.

I’m responsible for the care and conservation of the objects in the collection. The “care” aspect is split between me and the collections management team, which includes preventive things like monitoring humidity levels, controlling the environment, and dusting the objects. As a conservator, I’m often more responsible for the interventive treatment of objects or coming up with some of the standards for different media, like how long things can be exposed to light or how long they’re allowed to be on display. We have objects on view in the Mansion and the Donald W. Reynolds Museum and Education Center, as well as the outbuildings, and those have very different sets of requirements for conditions. I can also help with the characterization of and identification of materials. Not so much authentication, but rather what things are made of.

So you’re not the one answering “did George Washington own this?”

Right, that would be more of a connoisseurship angle. But I can address what things are made of: what type of metal, stone, or wood, for example. I trained in objects conservation, which means I have a diverse training in three dimensional materials and that’s pretty much anything—any work of decorative art, fine art, or even utilitarian objects. We train to be generalists, I’ll say that.

Right. Neale Nickels handles the larger architectural features and structural aspects of the Mansion or other buildings. I look after the pretty things that go inside! As an objects specialist, I work on three-dimensional things so I don’t really tend to work on textiles, paper, paintings, and even frames, which can be so complex that we will hire specialized consultants to work on those.

What have you been working on lately?

One of my projects is the mantelpiece in the New Room. We had two contract conservators treat the grate, which is made up of steel and cast iron. I was working on cleaning the marble. That’s the sort of thing that can be maintained by the collections management assistants and dusted on a day to day basis, but after years and years it accumulates so much grime that it needs a more interventive form of cleaning.

One of the New Room lustres or candelabra, before treatment. Mount Vernon Ladies' Association Purchase, 1932 [W-104/A]

I have also been working on two lustres, what we would call candelabra today, that are going in the New Room with the oval mirrors and brackets. I’m working closely with the curators on this because they have to inform from the curatorial side how they should be arranged.

They advise on what’s historically accurate?

Exactly. They have been able to tell me that there are certain components that are obviously later additions—which is not obvious to me from a materials standpoint, but it’s very obvious to them from a connoisseurship standpoint. I will be able to reconfigure the components to the original layout. That was a little bit of fun detective work. There are four arms on each lustre, two of which are candle holders and two are decorative ogee curves. There are letters on the receiver base and each of the arms is removable. It’s got a little cap on it and what’s nice is that on the bottom there are letters that correspond with those on the base.

One of the lustres, partially disassembled. One of the arms has been removed from the receiver base.

But we found that the letters don’t match up and there is actually some duplication, suggesting the arms were probably exchanged between the two lustres at some point. Assistant curator Adam Erby also has a historic illustration which shows a different layout. I changed the arms around until I could find the right permutation that matches what Adam suspects the layout to be.

The lustre with reconfigured arms. Because one of the decorative arms was broken and is now shorter, they are no longer symmetrical.

I’m also able to identify certain repairs. There is an old set of repairs done with staples. That’s something we’re going to leave in place because it very well might be an old repair with historic value.

In the conservation field, there is a distinction between conservation and restoration, but we do aspects of restoration. For example, one arm was broken in the past and somebody had repaired it just by sticking it into the cap. The problem is with the layout that it had, you didn’t notice, but in our new configuration, when you put these two side by side, there is a perceptible height difference that’s not going to work. I’m restoring it in the sense that I fabricated the missing section to add the length and I’ll cast that out of a clear resin so it won’t be as noticeable. It will be aesthetically integrated, that’s the phrase that we like to use. A lot of conservation work is cleaning and reversing past restorations which are damaging to the piece or aesthetically unappealing and distracting.

Two arms from the lustres. Karl fabricated the white section on the arm on the left to match the other arms that are intact. The final repair will be made from a clear resin.

This illustration, created with Photoshop, shows what the lustre might look like after repairs are made to the broken arm.

I that imagine with the technology and tools that we now have available, you’re able to improve on past repairs.

Absolutely. It may be difficult, they may have used an epoxy or something that they wanted to be a very durable and long lasting. One of the key tenets of conservation today is reversibility. I’ll use adhesives that not only will they be reversible in the future, but I’ll also take documentation of my repair, another key aspect of conservation. Those are within our code of ethics, the things we strive for: reversibility, documentation, archival materials—even our documentation itself needs to be archival so that it will still be around.

This is more in the collections management sphere here at Mount Vernon, but I’ve also been helping to advise on the construction of the mount that will secure the bracket and mirror to the wall. That’s being constructed by an outside contractor, but I can advise on what materials should be used for the mount that will come in contact with the object.

Karl with the two lustres in Mount Vernon’s conservation lab.

How did you become interested in conservation?