Digital Art & New Media, Art & New Media, Virtual Reality

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

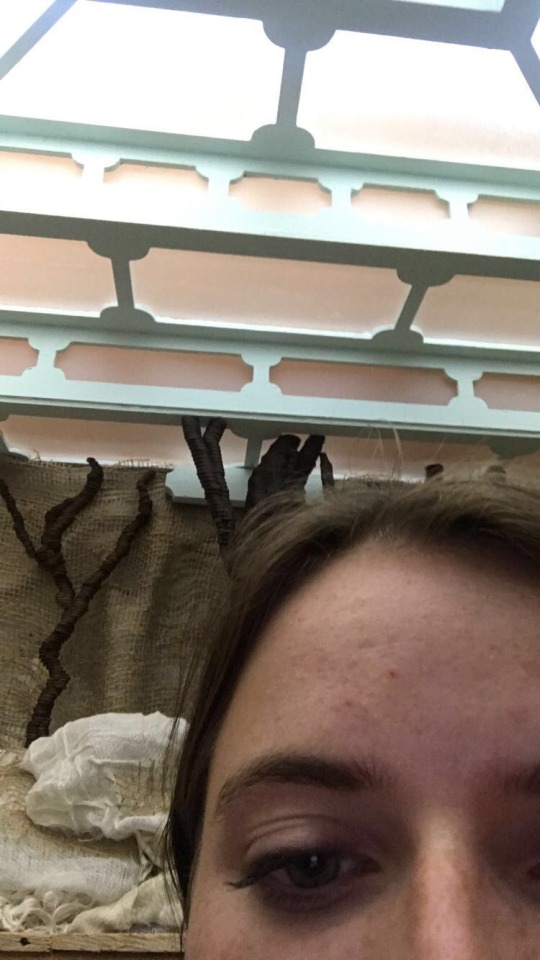

Safe House was a project that demonstrated what it was like to be alone and surrounded by nature on a different scale than we can experience in real life. This immersive project was filled with sound, lights, and different aspects of the environment, which transform when you open one of the doors and interact with the project. Upon opening a door, a storm begins, which shows how both nature and human emotion can drastically transform when changes are made. I enjoyed this project because it was completely immersive and an experience that you can only have by yourself; nobody else can impact the experience that you have with this project, and what you get out of Safe House is based upon how you choose to interact with the environment around you.

While I only took a selfie with the first project, the next two projects I still found very interesting. The first was Pixel Light, which focuses on how users can interact with light to alter their experience. When activated by motion, which the motion sensor reads as the user interacts, a picture, like the one below, decorated the LED screen. I liked this project because it was constantly evolving and presenting new images, so that as the viewer continued to engage with the project, the experience itself continued to develop. With a focus on light in art as well as evidenced through my posts about neon art, I find the interaction between light and art interesting as well, so it always catches my eye when someone finds a new way to intertwine the two.

Another ITP project that I was interested in was Artificial (?) Anti-dancer, which was a project that turned everyone who participated into a dancer, depicted as a stick figure against the wall. The project captures the motion of the participant and conveys it on the wall, mimicking the participant’s movements. Upon reading more into it, the whole project consists of this interactive aspect combined with a stick figure generated by the creator, dancing alongside the living participant. While I was originally interested in this project out of its entertainment value, as an avid fan of the Just Dance series, the complexities of this project are what become more significant. The juxtaposition of the human movements next to that created by a human, but developed via program as opposed to depicting natural human fluidity, is intriguing to explore. What does programmed movement look like adjacent to natural dancing? This project interested me not only because of the interactive element with the dancing, but the technological versus natural question it poses as well, which adds another complicated layer to the project itself.

0 notes

Text

In the final portion of Rheingold’s virtual reality that we read, Rheingold begins discussing the biology of the optic system and how it affects virtual reality as it continues to be developed. Heilig began to center his focus upon how he could get the technology to mimic the optics of the brain so that it could accurately present reality for the viewers in how they see the animated world before them. He goes into detail on the concepts of motion parallax and binocular parallax, explaining how they create motion and 3D in these virtual worlds. Rheingold, in referring to the presence of sensory illusion in virtual reality, introduces the technology behind stereoscopy. “Stereoscopy was the first technology to package visual information designed to match the binocular aspect of visual ‘unwrapping’” (64), which was engineered in 1833 by Wheatstone. Stereoscopic displays are very similar, but the technology differs in the way images are presented to the human eye. Rheingold goes on to detail specific technological aspects of each stereoscopic method and expands upon Wheatsone’s technological accomplishments, past just the stereoscope. Wheatstone designed a new method of tricking the human eye, creating a “drawing device that consisted of two drawings of the same scene, but each through slightly different perspectives corresponding to human interocular distance, then present each image to one eye, human vision will fuse the two images together into one three dimensional scene,” creating a continuous illusion.

0 notes

Text

Within pages 54 to 63 of Rheingold’s accounts on virtual reality, he continues to detail the history of virtual reality and how it was both conceptualized and actualized as technology continued to advance. In its early conceptualization, Fred Walker invented Cinerama, which was experimentation with a combination of multiple projectors and screens as a manner of presenting a wider field of view for films. He ultimately got a contract with the Air Force and built the motion picture display for the first flight simulators, which stands as one of the early advancements of virtual reality. He accomplished this utilizing multiple cameras, and post-war, he brought this idea back in relation to entertainment, attempting to get Hollywood to work with three projectors and three cameras so that the screen could wrap around the audience, thus improving their perceived sense of presence and involvement with the film itself. Walker, and soon Heilig, knew that the film industry was threatened by the up-and-coming significance of television, so they found Cinerama and 3D to be important to revitalizing the film industry. Heilig, in the late 50’s and early 60’s, followed in Walker’s footsteps, but turned toward the idea of duplicating human sensory information in order to create the “experience theater.” Heilig, like Walker, called for Hollywood to make a change and take interest in his ideas, but because of his inexperience with Hollywood, nobody listened to his ideas. He yearned for theater to become a more immersive experience, so that there would be a wraparound screen, vibration, R&D sound, and even smell and wind elements. The most intriguing part of his call appeared to be his desire for the image to adapt to the viewer’s gaze, in that the center of the viewer’s focus will be a very sharp image while the surrounding periphery would get blurry, as does the human gaze.

As Heilig worked to combat the rise of television, he took upon the project himself and created a company Sensorama, based upon the notion of creating what he would deem to be an “experience theater” for one person at a time. This would thereby personalize the experience and allow each person to fully immerse themselves in the film that they are watching. He garnered two patents in his duration of working to generate Sensorama; the first was granted on October 4, 1960 and it was titled “Stereoscope Television Apparatus for Individual Use” and the second was granted on August 28, 1962, and this was simply called “Sensorama Simulator.” Heilig noted how there was better learning efficiency in audience’s when they were fully immersed, and he thus dedicated a lot of his time and life to making his goal become a reality. Rheingold, after going into depth on Heilig’s exploration of “experience theater” and Sensorama, delves into the concepts of “enabling technology” and “convergence,” which both have aided and transformed the path of virtual reality as it has been further developed over the years. Enabling technology is defined as a technology that makes a resulting technology possible, which is what virtual reality needed before it could take off and ultimately find success. Virtual reality had to wait for the computer to become technology adept so that it could be utilized in the fruition of virtual reality. Rheingold discusses “convergence” as well, which is defined as “related to enabling technology, apparently unrelated scientific or technological paths may converge to create an entirely new field,” which happens quite frequently in the creation of new technologies. For example, American public appetite for culture and technology from the Air Force combined to drive the success of the television, and convergence was necessary in the development of virtual reality as well; computers and optically based viewing devices converged to lead to the birth of virtual reality, and, because of this convergence, virtual reality has grown into what it is today.

0 notes

Text

Netflix’s recent documentary series, Abstract: The Art of Design, captured the essence of this illustrator who often designs front pages for the New Yorker among the other magazines and media that his art appears across. Niemann, currently based in Berlin and often working in New York City, spends his nine to five workday in his office illustrating for the various jobs he is hired for, oftentimes working on designing cover pages for various New York based magazines. Niemann focuses a lot upon the idea of the abstract, taking the time to define the abstract and differentiating between what is abstract, realistic, and “just right,” using the heart as an example. Currently, Niemann is working upon a The New Yorker cover that’s based upon augmented reality, so he plans to design a cover that has the potential to pop out at the viewer when they are viewing it through a virtual reality medium. Niemann has developed 22 covers thus far, and with the success he’s had with all of them, his involvement will merely continue to increase. The manner in which he designs the covers is intriguing as well, in that he notes how “inspiration is for amateurs, professionals just get to work” when considering how some artists say that they cannot work unless they have the inspiration to do so. Niemann’s work focuses on letting the visuals speak by themselves, similarly to how a pianist uses the piano to speak for him. His work is never finished, since an artist must continually refine the way he speaks.

His works that are detailed throughout the documentary include the New Yorker covers alongside his instagram series “Sunday Sketches” and his iphone application “Chomp.” Both concepts, he notes, are rather useless, but they rather serve as a form of entertainment and to inspire intrigue in the minds of his audience. When discussing Chomp, it’s interesting to consider how he is careful how much control he gives to the participants. In a world where virtual reality developers are looking to give more and more control to the participant to enhance the experience, Niemann wants to do the opposite. He wants the power to surprise his viewers throughout the experience, and he believes that providing the viewer with too much control removes from the “abstract.” Niemann’s initial interest in art is quite intriguing as well, in that the “gateway drug is not creating the art, but experiencing it.” Niemann often enjoys traversing exhibits, garnering different experiences with different pieces that have then transformed, however minimally or extensively, his relationship with not just art itself, but the way he creates his own art. When art reflects his own feelings, Niemann recognizes that this allows him to empathize more with an increased understanding that he is not the only one who feels this way, which therefore makes him recognize that he is alive and going through the same experience as those around him. This drives the argument that art is both an individual and shared experience, since he can reflect on the art himself and realize that those around him and the artist himself may share the same feelings.

0 notes

Text

PlayStation VR is releasing a new game called The Persistence, which is a survival game that combines “procedural generation” and “roguelike mechanics” in making a game that the author of the review believes fits the virtual reality medium perfectly. The base storyline of the game is that you are a character “on a starship who is awoken from sleep after all of the previous crew was either murdered or transformed into a hideous monster” (Jagneaux). The goal is to reach the far end of the starship and get the ship back to Earth, but every time your character dies you are awoken as a new character, but the layout of the starship transforms so that you cannot rely on your previous knowledge of the starship. Even though this game is a single-player game, there is an option for a second screen to come into the picture to either help or hinder your progress. The second player’s screen displays the layout of the starship and where enemies are, and gets XP for aiding the first player, but they can turn against the first player as well; the second player may be incentivized to put the first player in harm’s way, or even the first player may direct viruses at the second player in order to essentially steal the second player’s XP. This game not only focuses on the mission of a single-player, but it fosters an interesting dynamic where the two players must completely trust each other, or else they will be unable to complete the goal of the game.

The author of the review, David Jagneaux, was impressed by the aesthetics of the game as well, admiring both the motion techniques and the literal appearance of the game. Jagneaux comments that the lighting and general coloration is far better than most virtual reality games that are currently available, and even though he mentions a few issues with certain objects or animation, these flaws do not hinder his opinion of the game itself. Jagneaux focuses on the technology behind the motion in the game as well, describing the manner in which the movement was based upon a DualShock 4 controller, which aims to help curb the motion sickness that many people have associated with virtual reality programs. The Persistence is slated for a May 2017 release, and it’ll be important to keep up with how prominent it ends up becoming within the realm of virtual reality, since it could change the way that both the games themselves are designed and how motion will be dictated within these virtual reality worlds.

0 notes

Text

In March, director Shirin Anlen released a 3D spatial documentary titled Tzina: Symphony of Longing, which follows the lives of those who spend their time in what was once Tzina Dizengoff square in Tel Aviv. Anlen was inspired by the people he’d notice in the square day after day, spending their time alone, “yet somehow in sitting together like this there was a sense of belonging” (Holmes). Anlen shot the documentary using a 3D Kinect, which was done so that users could interact with characters and drive the narrative of the story forward. This intensifies the immersion of the documentary, so that users could get closer to the characters throughout and develop deeper understandings of their individual stories. The documentary focuses on ten central characters and their stories, which make up the 45-minute documentary. Alongside the character-driven storylines of the documentary, the design and presentation of the film are pivotal aspects of the intrigue associated with Tzina. Taking notes from animator Chris Landeth and his work on Ryan, in which Landeth weaves animation and documentary footage in order to engineer another way of looking at the story. Anlen integrated this type of animation into Tzina, which he felt brought viewers closer to these characters who are all struggling with their personal problems.

Aside from the characters themselves, Anlen recognized the importance of Tzina Dizengoff square itself, especially considering the fact that it was undergoing demolition soon after the project. Anlen, realizing that destruction of the square was imminent, saw her project not only as an ode to the many people who found their home in the square, but as an ode to the square itself so despite its destruction in real life, it would still virtually exist. She replicated the structures, textures, and placements of the entire square into her documentary, allowing the square to live on. The final significant aspect of Anlen’s documentary is the ability for multiple people to share the experience, since every user sees others as pigeons, simply making their way around the square and listening to the stories of the people there. This shared experience allows people to, essentially, experience loneliness together, similarly to the people who inhabit the square. Anlen relays that “Tzina is a story about lost love and loneliness,” and that “the more you let go, the more the project will give back,” thus capturing the complete immersion of the documentary as it relays stories that a majority of users will be able to connect to.

0 notes

Text

Alongside the The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, the Jewish Museum’s other exhibit featured was Pierre Chareau: Modern Architecture and Design featured virtual reality as a medium of looking into the past. Chareau, over his career, rose into prominence in terms of French furniture and became one of the most sought after interior designers in the country. The exhibit itself provides many different manners of viewing and appreciating Chareau’s work, from the shadows traversing the walls around the furniture, to the collection of art that he and his wife cultivated over the many years, to the virtual reality headsets for viewing what a room he designed would look like, and even a moving screen that pieced together different parts of a house that reflected his design technique. The virtual reality portion of the exhibit is worth focussing on, with its four differing headsets and four different interior designs to discover. The exhibit consisted of a chair and a virtual reality headset, with each chair facing a different corner of the room. Some corners contained specific objects that were a part of the experience both virtually and in reality. This reflects the up-and-coming use of virtual reality as a method of planning architectural projects and even real estate sale, in that people will take a virtual reality tour of the house or the planned building and decide whether or not there are faults that must be fixed before the project or deal moves forward. This part of the exhibit reflected that, and it was interesting to see how even though this is an application of virtual reality that deals with real-life purposes, it can still be intertwined with art to display the work of a renowned architect.

0 notes

Text

Google has worked to introduce those around the world to the lifestyle in the favelas in Rio de Janeiro through their recent innovations in virtual reality technology with a project titled Rio: Beyond the Map. They have developed a project similar to that of New York Time’s Daily 360 and Clouds Over Sida, which aims to cultivate empathy within others who do not know about these different areas of the world. This 360 degree exploration is led by a virtual host who also is a resident of the favelas, and the host guides viewers through this tour of an area that is not anything like the lives of those who are most likely viewing it. The favelas are home to approximately 1.5 million people, yet the favelas are still largely unmapped, so that even those who live around that area do not know much about them. As the host takes the viewer through the favelas, to help foster empathy the host tells stories about individuals who live there, so that the experience becomes more intimate as the viewer learns about the personal lives of those who live in the favelas.

Alongside this 360 degree video that Google has developed, a few years back they released “Ta No Mapa,” which is a program that partnered with the nonprofit AfroReggae in order to teach residents of the favelas in digital mapping. This fostered an increase in mapping which has put 26 favelas on the map along with approximately 3,000 local business, which went on to help them garner more business. This mapping turns more attention to the favelas in a way that hopes to detract from the negative stereotypes that they have inherited. One of the narrators in the tour explains “most people only know the favelas through the news—crime, poverty, and violence. But that’s only a small part of the story…the favelas are not simply a place, they are a people, and to understand them, you must go inside and see for yourself” (SingularityHub). Virtual reality allows for this expansion of understanding within the favelas, and promotes the significance of empathy when considering the vastly differing regions of the world. Google hopes to continue developing virtual reality projects like this one, driving people to learn more about those who come from, typically, unheard of areas throughout the world.

0 notes

Text

The Jewish Museum recently exhibited The Arcades: Contemporary Art and Walter Benjamin, which was an extensive exploration of Benjamin’s work. Benjamin was a German Jewish writer and philosopher, and The Arcades Project was his last work, remaining unfinished when he passed away. The collection began as an observation that Benjamin made on shopping passages, but as he continued to write, the collection grew into the vast project that it became. The Arcades Project “offered an ideal prism through which to examine the era’s capitalist metropolis and the phenomenon of modernity that had its origins there” (TheJewishMuseum). The project combined many differing media to observe these many pieces of society, but with the beginnings of World War II forcing Benjamin to give the works to his friend to protect them, the works were not fully completed and it was not until many years later that they were even discovered.

The Arcades Project includes thirty-six chapters, and the exhibition in the Jewish Museum captures each chapter with varying media to accompany the written portion by Benjamin. The aspect of the exhibit that I found particularly striking as I walked through covered Karl Marx and his final resting place, in which he had more than one “final resting place.” Because people struggled to find his grave and the resulting petitions, Marx’s body was moved to the main avenue of the cemetery so he would be easier to find. The spot of his original grave is marked by a stone, which has withered down and become broken, vulnerable to insects and plants wanting to traverse the stone. This piece, the video installation especially, depicts several of Marx’s ideas, which is noted in the description of the exhibit. The abstract notes how the social insects that are crawling within the broken stone have “perfectly integrated communal lives [that] offer a tempting prototype for ideal human societies such as those that Marx envisioned.” Later, the piece even notes how “the story of Marx’s migrating grave suggestively echoes the shifting legacy of Marxist philosophy,” which alongside the video installation, grave image, and Benjamin’s excerpt from The Arcades Project, displays a complicated and unique position on Marx and his position as a social theorist.

0 notes

Text

Helen Greene fulfills the role of both Executive Creative Director and President of the production company Greenhaus GFX. Greene is a motion graphics producer who has helped grow Greenhaus into a full-scale production center where a group of designers work to produce motion graphics, title designs, and editorial work. Under Greene’s direction, the company has earned Golden Trailer Awards in the Best Motion Title Graphics and Best Motion Posters. They have worked for Disney, Paramount, Netflix, and Warner Bros. Greene herself has two BFA degrees from Minneapolis College of Art and Design and Art Center College of Design in California. Before she turned her attention to title sequence design, she spent many years in movie marketing. Her most well-known work comes from the title sequences from films such as Fury, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles 1 and 2, Insidious: Chapter 3, and Entourage. One of Greene’s more recent sequences is 2014’s Fury, David Ayer’s war film starring Brad Pitt and Logan Lerman. This sequence, which differs from the rest that I’ve studied, is played at the end of the film, with Fury beginning with a simple title card. This sequence is displayed toward the end of the film, and it features imagery similar to that of archival World War II footage. The music is a pivotal aspect of the sequence, since Steven Price’s piano piece directs the sequence and the visuals follow. The sequence is edited and cut based upon the music, which “provides resonance, energy, and ultimately a strong finish” to Fury.

0 notes

Text

Olga Capdevila is a Spanish illustrator and designer who is currently working out of Barcelona. She earned degrees in art and design and illustration from Escola Massana, and she used her education to found Tropèl Illustració, which is an independent company that intertwines illustration, motion, design, and performance. Capdevila has worked for mostly Spanish products and advertisements, including Spain’s TV3, Reebok, Moscou Club, and the musical group La Iaia. Capdevila was also the art director on the opening for 2015’s Blanc Festival. Capdevila’s most prominent work was this opening for the Blanc Festival, which is a two minute and thirty second ode to Spanish graphic design. The title sequence, “True Hot Stories,” is described by Art of the Title as a “hot and heavy animated romp,” which was one of the more complex designs that Capdevila has been a part of. The production team, essentially, consisted of Capdevila and animator Genís Rigol, and they worked with Photoshop and After Effects to create the colorful opening. Capdevila began designing around a core palette of colors, which featured “black, turquoise green, light blue, and pink,” which informed the colors that would be found within the characters and the rest of the sequence. The color palette and the typeface informed the way that Capdevila produced the opening, which drove the characters to take on the colors mentioned within the palette and be drawn with thick lines to match that of the typeface, which was developed specifically for the festival. This sequence, despite being deemed inappropriate by some, matches the playfulness that Capdevila wanted to capture, and she is very much proud of this work and the small intricacies she and Rigol hid among the sequence.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Belinda Bennetts is an Australian designer who has worked on the title sequences for many films over the span of her career. Her design credits include Little Women, Paradise Road, Oscar and Lucinda, and Charlotte Grey, and she has worked on several television series as well. Aside from designing title sequences, she has undertaken other artistic roles in the creation of films alongside her title sequencing roles; Bennetts acted as the VFX Art Director on Moulin Rouge and the Crowd DT on Happy Feet 2. Her career spans past artistic development, in that she is a professor of motion graphics at the Australian Film, Television, & Radio School as well. Her current path contains a focus on acting as a UX designer in Sydney. Among Bennetts’ most famous work is her title sequence for 1994’s Little Women, which, alongside the film itself, was immediately well-received. The sequence relies heavily on typeface, which is “set atop woodblock illustrations” and “calligraphic ornaments, flourishes with graceful curves over fields of snow.” This sequence exhibits many different visuals, all of which aid in introducing the lives of the March sisters. The sequence features mostly dark colors, decorated with hues of blues and blacks that still, nonetheless, feels warm to the audience.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Wenden K. Baldwin, based in Los Angeles, is a visual effects producer and title designer. Her career began in print advertising, since she worked for Cannon Films. She subsequently began the title department at the same company after she created the title sequence for Maria’s Lovers in 1984. After her breakout title sequence, she began to collaborate with many famous directors on various other title sequences, such as Invaders from Mars, Masters of the Universe, and Bloodsport. Aside from her work for Cannon Films, Baldwin produced title sequences for Cinema Research Corp and Pacific Title and Art as well. Between these two companies, she designed the title sequences for The Scarlet Letter, Universal Soldier, and My Best Friend’s Wedding. She continues to make title sequences today, even though she now mostly works with independent filmmakers. Baldwin took on the role of title designer for 1997’s My Best Friend’s Wedding, which is now widely considered one of the best romantic comedies. The title sequence depicts a quarter of performers singing “Wishin’ and Hoppin,’” which was choreographed by Toni Basil. This title sequence was unique through including a full performance, which felt similar to a ‘50s title sequence that one might see before an episode of their favorite television show. Baldwin was very involved throughout the hands-on process, especially focussing on developing the typeface and making sure that, because it was script, it would line up properly with the shots and the choreography.

0 notes

Text

Kathie Broyles, based in Colorado, is a title designer who originally worked in music but shifted her focus to film and broadcast design. She works mostly under her own name, but the companies that she has done work for include LucasFilm, Touchstone, Twentieth Century Fox, Warner Bros., Disney, Sony, and many more. Throughout her career and among her extensive portfolio, title sequences that stick out are Say Anything…, thirtysomething, Beverly Hills 90210, My So-Called Life,and Courage Under Fire. Broyles’ most well-known work is the title sequence for 1994’s My So-Called Life, a show which reflected the 1990’s grunge culture and gained the admiration of many fans during its run. An important part of the sequence is the song, which many believed perfectly encapsulated the “anticipation, growth, aggression, and confusion” that are so prominent throughout high school. The title sequence was built around several shots that Broyles and director Scott Winant agreed both reflected the show itself that were not only to be in the pilot, but should be intertwined within the sequence as well. Another aspect of the title sequence that is particularly fascinating is the one moment where the sequence moves in slow motion, which is a shot of a shared look between Angela and Jordan as Angela walks down the hallway. Scott notes that this shot is in slow motion because the show is Angela’s perspective, so that the filming must match the way that she perceives the world around her; when she sees Jordan Catalano, her love interest, her world slows down, therefore, the camera captures this in slow motion.

0 notes

Text

Arisu Kashiwagi is a New York City based graphic designer and director who has worked for many different television networks since 2005, designing an array of title sequences for network shows. The companies that she’s worked for include VH1, 2X4, Prologue, Psyop, and Imaginary Forces among others. The shows that she has developed title sequences for within these networks are Marvel’s Jessica Jones, Boardwalk Empire, The Pacific, and Magic City. Because of her part in creating the sequence for Jessica Jones, Kashiwagi received an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Main Title Design. Aside from her work in television shows, Kashiwagi has also done design work for Playstation video games and other brands, such as Prada, NYCxDesign, LA Opera, and Johnny Walker. Among the many television sequences that Kashiwagi has had a role in designing, her original biography did not mention her part in last Summer’s largest television hit; she helped design the title sequence for Netflix’s Stranger Things, capturing the 1980’s essence with the emphasis on the typeface that matches that of many of Stephen King’s 1980’s paperback novels. Aside from simply the typeface, the music in this sequence is significant as well, with the eerie chords coming straight from an 80’s film. The title sequence relies on 80’s nostalgia, and, through the efforts of Kashiwagi and the rest of the design team, succeed in reflecting the “revered title design tradition” and becomes “a testament to the power of type in motion and the enormous potency of nostalgia.”

0 notes

Text

Alison Brownmoore is a title designer who has designed title sequences and in-film motion sequences for more than 45 movies, of which many won prestigious awards. These awards are dispersed over “13 Sundance films, five Academy Award shortlisted features, and BAFTA, Emmy, RTS, and Grierson award winners.” To continue along Brownmoore’s extensive list of accomplishments, in 2016 she garnered the SXSW Excellence in Title Design Award, was named a juror for the Titles and Graphic Identity BAFTA Craft Awards, and served as a mentor in The Dots VFX/Animation Masterclass. Brownmoore is a renown title sequence designer, and she even co-founded a design and visual effects studio in London called Blue Spill. A majority of her work is within documentary films, but she has tested the waters in television series as well with The Traffickers and Captive. One of Brownmoore’s many documentary title sequences is the design for We Are X, which is a documentary film about the wildly famous Japanese heavy metal band X Japan. The title design captures the high energy, wild nature of the band itself, the images pulsating to the beat of the band’s famed song “Jade.” At the peak of the song, the letter “X” flashes vibrantly on the screen, changing colors each beat before leading into many more bright images that encapsulate, along with the music, the loud, flashy feeling that the song and band exudes.

0 notes

Text

Elinor Bunin Munroe is an award-winning artist, earning more than 100 awards for her films and work within them. She has worked in title design, directing, and producing for both animated and live-action films alongside her experience in engineering title sequences. Her career has been spent as a “senior designer at CBS Television, creative director of WNET Channel 13, a painter, and a professor,” displaying her success in a large variety of fields. Her work includes designing the title sequences for many films like The Producers, Taking Off, and War and Peace and television shows consisting of The Rookies, The Great American Dream Machine, and Don Rickle’s Brooklyn. Munroe has entertained numerous careers in many different fields and has been wildly successful in her varied endeavors, and in 2011, the Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center was opened and named in her honor, depicting the vast amount of success she achieved throughout her career. Munroe was the chief designer on Lilith, a 1964 film, capturing the film through a central metaphor; the butterfly, acting as the title character, is entrapped within a spider web and struggles to free itself, which reflects Lilith’s storyline. Because of the time in which the design was completed, in the early 1960’s, technology for title designs clearly was not as advanced as it is now, but the simple design captures both the film itself and the audience’s attention before they even begin delving into the narrative that follows.

0 notes