Photo

A mudslide at an iron ore mine in Brazil, in which at least 13 people died, has reignited calls for safer ways to dispose of millions of tonnes of waste as toxic mud leaks into the Atlantic ocean

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Broadway, from A to Z

Submitted by yamandus

Broadway is easily America’s most famous thoroughfare. Starting in lower Manhattan at Bowling Green and running the entire length of the island, it strings together some nine to fifteen neighborhoods—depending on who you ask—before bleeding over into the Bronx, serving as a cross-sectional study of the City’s diversity in ethnicity, utility and design. As the Main Street of Manhattan, Broadway exhibits a catalogue of lettering—from neon lights to mom-and-pop shop signs, from theater marquees to building names.

The team at created this virtual tour of the typography of Broadway. These couple of images are a pale attempt to show you what you can see in the webpage. If you want to see a beautifully done page that marries typography, design and architecture. Check out Broadway, from A to Z !

Team:

AUTHOR: Gabriella Garcia

EXPERT: Ksenya Samarskaya

DESIGN: Sergii Rodionov

PHOTOGRAPHER: Lia Bekyan

DEVELOPER: Oleg Mokhniuk

Images and text via Broadway, from A to Z

835 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A barricade constructed by the Paris Commune near the Hotel de Ville (April 1871).

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

These unsettling, expressionless masks were actually a fashion staple for wealthy women in Elizabethan England (c. mid to late 1500s). They were called visards, and were used by women of status to protect their fair skin from the sun, given that tanned, browned skin was seen as a sign of poverty (women with sun-tanned skin were usually poor laborers). Today, however, one can perceive from these artifacts only a bizarre, nightmarish appearance.

6K notes

·

View notes

Photo

seduction of Lancelot

‘Le livre de Lancelot du Lac’, France ca. 1401-1425

Paris, Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal 3480, p. 33

567 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Musgum Earth Home.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Mayan Tablet with Hieroglyphics Honors Lowly King

A 1,600-year-old Mayan stone tablet describing the rule of an ancient king has been unearthed in the ruins of a temple in Guatemala.

The broken tablet, or stela, depicts the king’s head, adorned with a feathered headdress, along with some of his neck and shoulders. On the other side, an inscription written in hieroglyphics commemorates the monarch’s 40-year reign.

The stone tablet, found in the jungle temple, may shed light on a mysterious period when one empire in the region was collapsing and another was on the rise, said the lead excavator at the site, Marcello Canuto, an anthropologist at Tulane University in Louisiana. Read more.

363 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Raft of the Medusa, by Théodore Géricault.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Japanese National Treasure, Ashura Statue 阿修羅

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Villagers bulldoze 18th century chapel in Tlaxcala

Arturo Balandrano, the head of the historical monuments for the National Institute of Anthropology and History, Said I does not know why people in the township of San Pablo del Monte tore down the Chapel of Holy Christ.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Ceremonial Knife (Tumi)

Dated: 9th–11th century

Place of Origin: Peru

Culture: Sicán (Lambayeque)

Medium: gold, silver, turquoise

Measurements: H. 14 ¼ in. (36.2 cm)

Provenance: English engineer, late 1930s–ca. 1969; [Walter Randel Gallery, New York, ca.1969]; Alice K. Bache, New York, 1969–1977 (partial gift from 1974)

Metallurgy was the primary medium for the expression of the power of Sicán rulers; vessels, headdresses, body adornments, funerary masks, and tumis were delicately made with gold, silver, and arsenical copper.

Tumis are ceremonial knives with semicircular blades. Known on the Peruvian coast since the third century B.C.E., they often appear in Moche iconography, where they are used to cut the throat of sacrificial victims.

Tumis were also recently found in situ in the tombs of high-status Moche and Sicán individuals. Sicán tumis such as this one were exquisitely crafted by skilled metallurgists mastering the techniques of repoussé, soldering, and filigree.

Here, the handle is inlaid with turquoise and takes the shape of the Sicán Lord with characteristic crescent headdress, comma-shaped eyes, and pointed ears. The Sicán Lord is often interpreted as ñaymlap, the mythical founder of the Sicán dynasties, described in a sixteenth-century Spanish chronicle.

Source: Copyright © 2015 The Metropolitan Museum of Art

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lill Tschudi (Swiss, 1911-2004), Street Decoration, 1937. Linocut printed in dark blue and red, 24 x 20 in. Number 9/50.

92 notes

·

View notes

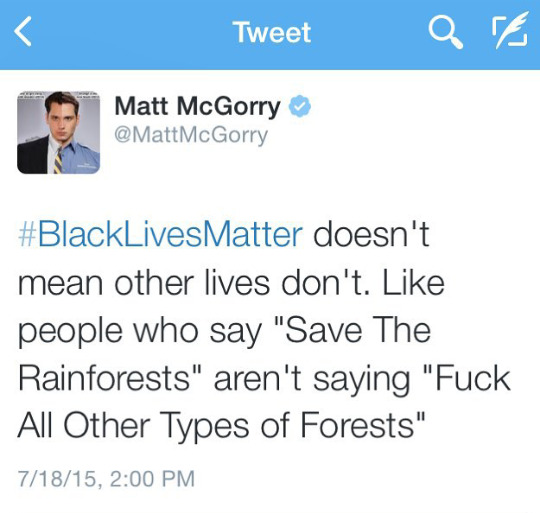

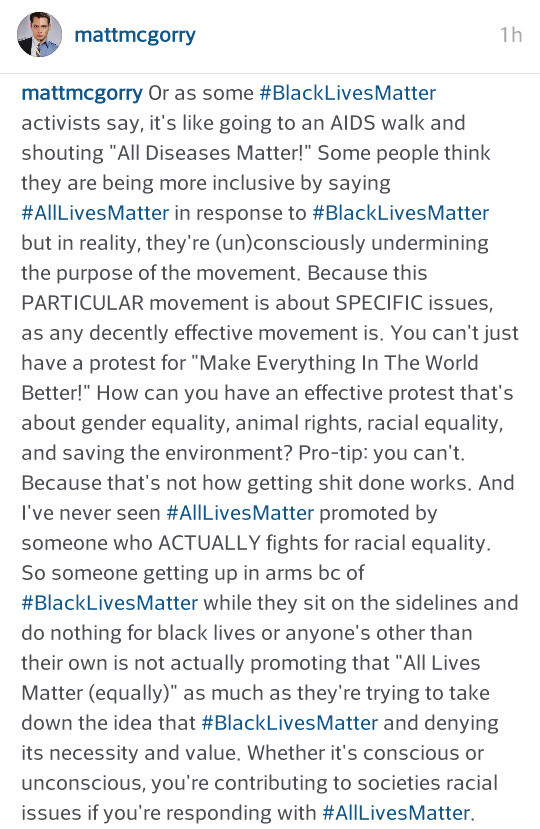

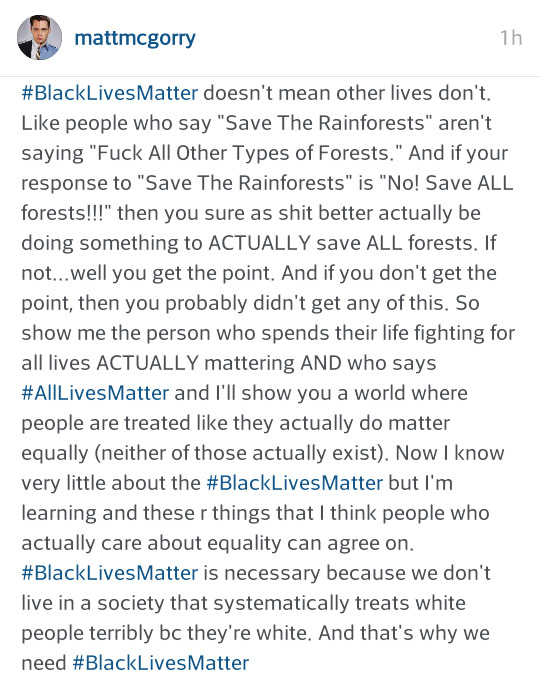

Photo

Non-problematic fave: Matt McGorry.

142K notes

·

View notes

Photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Neo-Babylonian Sagittarius Cylinder Seal, Mesopotamia, 7th Century BC

Made of agate showing a centaur (possibly Pabilsag) with a bow and arrow attacking a winged-lion (possibly a gryphon) demon. In the field is a star, a crescent, a fish (below the centaur), and scattered globes. The borders have a scroll pattern with drillings.

The Babylonian god Pabilsag was the precursor to our Sagittarius, the Archer. The image of the horse-centaur can only be traced back to the middle of the 2nd millennium (Kassite period in Mesopotamia) however the figure is undoubtedly older since the constellation name appears in the star-lists of the preceding Old Babylonians. The Old Babylonian period Pabilsag was identified with the god Ninurta. Little else is known about him exept like Ninurta, he was a son of Enlil. The earliest evidence of his worship can be dated to the 3rd millennium BC. He was the patron deity of the ancient city of Larak, which has not been located yet, but is possibly in the vicinity of Isin (modern Ishan al-Bahriyat, Iraq).

The familiar image of the Greek constellation as a horse-centaur armed with a bow and arrow is actually a simplified version of the Babylonian figure, which has been portrayed in several forms and combinations. Sometimes it has a set of wings, a scorpion’s tail and the head of a dog. Babylonian mythology says that Pabilsag’s family were represented in the constellations as well. His wife, the healing goddess Ninisina or Gula has the dog as her divine symbol, which may explain why some images of Pabilsag have a dog’s head coming out of his shoulders. Other depictions omit the wings or dog’s head and replace its back legs with those of a bird, while some images look more like the Greek version of a centaur.

Read more about Pabilsag here…

228 notes

·

View notes

Link

Fifteen years ago I visited Nishijin, Kyoto’s famed kimono manufacturing quarter with my then host family. I had just finished reading Yasunari Kawabata’s “The Old City,” a novel steeped in Kyoto’s kimono culture; its main character Chieko is the adopted daughter of a kimono merchant. I misunderstood the novel’s elegiac tone, and naively expected to see the Nishijin that Kawabata knew 50 years ago.

I got a rude shock. The district looked gutted, there were apartment buildings everywhere and only a few traditional dwellings and workshops in between. We passed a kimono merchant’s house that was being demolished. “There’s Chieko’s home,” I said.

We visited one kimono workshop and the owner kindly agreed to show us around. His family had owned the workshop for 140 years, he said, and now times were tough; customers were dwindling and nearby workshops were closing down. We saw a computer programmed jacquard loom, and on it there lay the answer to some questions I had in my mind — an exquisitely beautiful kimono obi worth $8,000.

Japan’s kimono industry has long been in decline. After 1945, Japanese women abandoned their role as bearers of Japan’s fashion traditions and embraced Western styles, and the market for high-end kimono is now collapsing as wealthy customers opt for cheaper, more casual fashion.

A recent Asahi Shimbun article explained that between 1982 and 2012 kimono sales declined from ¥2 trillion to one tenth of that figure, and kimono tailors’ numbers fell from 6,300 in 1984 to 1,351 in 2014.

In Kawabata’s novel a traditional kimono weaver predicts that if any business like his survives the coming decades, it will only be because it is “under government sponsorship as an ‘Intangible Cultural Treasure.’ ” This seems like only a slight exaggeration in hindsight.

So now the kimono industry is trying to innovate, to diversify beyond the formal, conventional styles that had been its mainstay, and to seek out overseas markets, much as it has done in the past. There is a genuine conversation to be had among non-Japanese about how to help preserve and respect this industry, but as we shall see, it can go terribly wrong.

A recent “Looking East: Western Artists and the Allure of Japan” exhibition in Japan and America, organized by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and Japan’s national broadcaster NHK, incidentally incorporated some promotion of kimono culture.

Showcasing the works of 19th century European impressionists alongside works by Japanese artists that had influenced them, the exhibition included Claude Monet’s 1876 painting La Japonaise, a wry comment on the contemporary French rage for Japanese art that features his wife in a formal kimono.

For the Japanese tour, NHK commissioned some gorgeously embroidered uchikake like the one Monet’s wife wears in the painting, and patrons were invited to try them on and be photographed in front of the painting.

After the painting returned to its home in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, it was exhibited again in late June with the kimono try-on sessions scheduled to continue into July as “Kimono Wednesdays” for American patrons.

Then something off-script occurred. A small group of young protesters, mostly Asian-Americans, came to the first Kimono Wednesday event with placards to protest its “Orientalism,” “racism” and “cultural appropriation” which they claimed was victimizing Asian-Americans.

The protesters created a Facebook page, “Stand Against Yellowface,” and posted sophomoric manifestos on Tumblr featuring tone-deaf karaoke of their hero: the Palestinian scholar Edward Said, author of “Orientalism,” a central text for postcolonial theory syllabuses in American liberal arts faculties.

A social media battle ensued. Twitter hashtags appeared — or, like #whitesupremacykills — were appropriated, provoking widespread derision, while the Boston Museum of Fine Arts Facebook page was inundated with accusations about the exhibition’s “racism” and “Orientalism.”

On July 7th the museum canceled the kimono try-ons and restricted patron access on Kimono Wednesdays to touching the uchikake. International media coverage by the BBC and the New York Times gave the protests a wide audience.

Japanese-Americans, Japanese residents in the United States and their supporters counter-protested at the museum and on social media in vain. Counter-protesters pointed out that very few of the protesters were Japanese, and that they had no right to dictate what counted as racism or cultural appropriation against Japanese or Japanese-Americans. They complained that the protesters had chosen the wrong event to protest against with their parochial identity politics agenda.

Some wondered if Edward Said’s “Orientalism” thesis was relevant to the controversy. That thesis argues that the knowledge-based enterprise of 19th-20th century Western scholars and artists classifying and representing Middle Eastern and African societies was itself an expression of colonizing power, essential to the West’s self-definition as it sought to dominate those societies. Cultural borrowing from these societies thus also amounted to “cultural appropriation.”

Said’s thesis hardly applies to the Japanese or Asian-American cases. When early 20th century French designers “appropriated” kimono styles and transformed European women’s dress lines, Japanese textiles manufacturers happily accommodated these trends.

For their part the Japanese reciprocated with their own fascination for, and assimilation of Western fashions. By then Japan was also a colonial power which was turning its own Occidentalist gaze — and naval guns — back on the Western powers. In such circumstances, Western fascination with Japan’s exotic arts and fashions fits a loose definition of Orientalism, but it is more benign than Said’s thesis allows for.

As for the protesters, Said would have mocked the ressentiment of alienated middle class Americans wallowing in victim cosplay. Their denunciation of Kimono Wednesdays as “a clear dismissal of our country’s current struggles regarding race and racial violence” that “propagates … the Orientalist gaze, inherently white supremacist and misogynist” was a comic misconstrual of an event originally conceived by Japanese and American sponsors to celebrate cultural exchange.

Objections like this fell on deaf ears, and will probably do so again once another “cultural appropriation” controversy erupts — if, say, pop singers perform in “Orientalist” kimono cosplay like Katy Perry or Nicki Minaj have in the past, provoking the obligatory social media pile-on.

But why should anyone worry about such controversies? Author Manami Okazaki, whose book “Kimono Now” analyses modern kimono fashions, told me that her main worry was “that this (protest) will affect museums/ event organizers wanting to do kimono shows in the future, which is the last thing the industry needs.”

Jargonistic polemics against cultural appropriation and self-appointed experts on sartorial “cultural respect” may also sow confusion about when, or how, it is culturally respectful for non-Japanese consumers to wear kimonos.

If posing in an uchikake before Monet’s painting is “yellowface,” when is it not “yellowface” to wear a kimono? Now that Uniqlo is selling yukata, or casual kimono, in its foreign stores, this is not an academic question.

Yet unlike the international media, Japan’s mainstream media barely touched the story. There was also a muted reaction from the fashion and cultural establishment within Japan.

Japanese social media briefly lit up in exasperation and bewilderment. People were mystified that anyone could accuse a kimono try-on event of being racist or imperialist. Few comprehended the identity politics assumptions driving the protesters. Some right-wing nationalists assumed they were anti-Japanese Chinese and Korean agitators.

Perhaps for the mainstream Japanese media and for many fashion commentators such a controversy is of little concern, being just another inexplicable skirmish in America’s culture wars. But it is more than that; if casual yukata styles are to attract foreign consumers who are also sensitive to social justice issues, a clear message needs to be communicated to them by Japanese supporters of the industry.

That message, recently iterated to me by an employee at the Nishijin Textiles Center in Kyoto, is this: Anyone can appropriate and creatively modify kimono styles whenever and however they like.

This message should be broadcast to counter those who misguidedly oppose the appropriation of Japan’s fashion traditions by “the West.” Japanese are not the West’s victims, and the kimono industry is ill-served by obsessions about Orientalism and politically correct “understanding.”

Kaori Nakano, a professor of fashion history at Meiji University put it to me this way: “Cultural appropriation is the beginning of new creativity. Even if it includes some misunderstanding, it creates something new.” It may be the key to the future of kimono fashion.

4 notes

·

View notes