For Queer History, and Histories and Sociologies of Gender and Sexuality.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Trans Feminism and Women's Liberation

I've just published this article on the historical overlaps between trans and cis feminism in Britain. The article argues for a move beyond narratives of inclusion and exclusion and highlights how trans feminists were part of women's liberation. It argues that trans and cis feminists worked together to promote bodily autonomy and advance critiques of hetero-patriarchal medical authority. This work was not always harmonious, but it did happen.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1468-0424.12767

0 notes

Text

Lillian Harman, anarchist feminist

Harman, an anarchist feminist, was born in Missouri in 1869. She campaigned in support of sexual freedom and for marriage outside the bounds of state and church control. Harman criticised the ways the state used marriage to enforce women's legal subservience to their husbands. She entered a "free marriage" (getting married without any legal documentation and keeping her surname). For this, Harman was sent to prison for contravening the 1867 Kansas Marriage Act. After this, she continued to push for sexual freedom and to publish anarchist feminist works.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thirty-year-old Tamara Rees showed what trans empowerment looked like in 1954. She fought Nazis, taught parachuting, and traveled the world... but her biggest hurdle came when the press learned of her identity.

1950s news coverage of Tamera Rees' transition shows a time before the trans moral panic. Most stories considered her brave or heroic for her openness. National papers would even celebrate her wedding in 1955. At worst, her narrative was seen as banal and unnewsworthy.

The New York Daily News ran a surprisingly respectful series of articles on trans people in the 1950s. Tamara Rees' were among the longest and most detailed. She thoughtfully implored the public to respect not only her identity but also other trans people like her.

Tamara wasn't the first famous trans woman of the 1950s nor was she the best known. However, she had a unique opportunity to share her own story. You can read Tamara's 1955 autobiography, “Reborn”: A Factual Life Story of a Transition from Male to Female, at http://transreads.org/reborn

676 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gluck

Gluck was a British painter, born to a Jewish family in London in 1895. Gluck used masculine gender presentation and rejected gendered suffixes and prefixes.

0 notes

Text

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin

Jenny Lives with Eric and Martin by Susanne Bösche was published in Danish in 1981 and in English in 1983. This was a children's book about Jenny, who lived with her father and his boyfriend. The book aimed to promote greater understanding of non-heteronormative families. In the UK, a copy of the book was available to teachers via the Inner London Education Authority. When news of the book's (limited) availability to teachers was picked up by the British press, there was outrage about schools supposedly promoting homosexuality to children. In 1988, Section 28 of the Local Government Act was introduced, banning the 'promotion' of homosexuality in schools and by Local Authorities. Section 28 was repealed in Scotland in 2000 and in 2003 it was repealed in the rest of the UK.

0 notes

Text

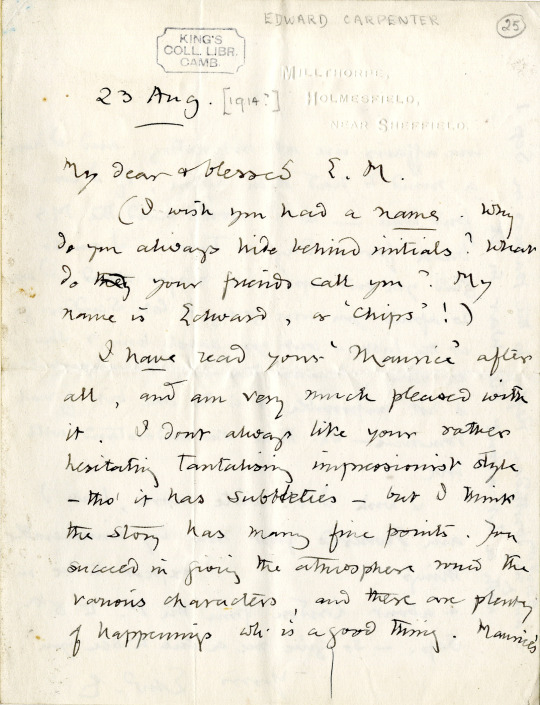

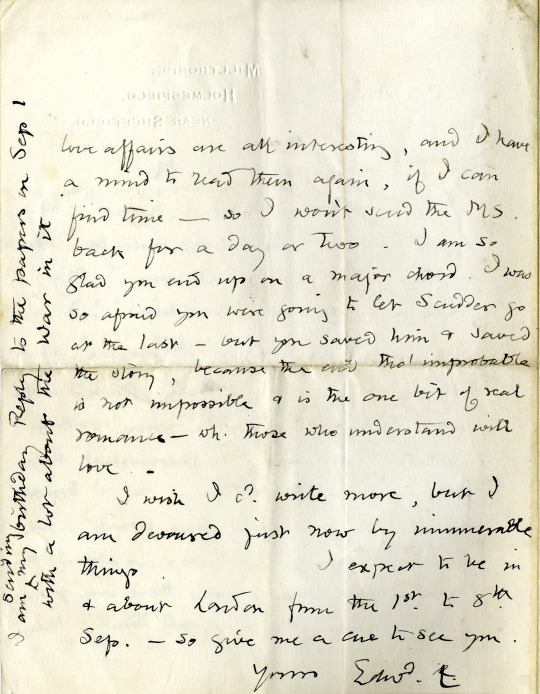

Edward Carpenter's full response letter to E.M. Forster after reading Maurice in 1914.

(The images of the letter can be found here at King's College's archive. Below is my transcription followed by photocopies of the letter. )

PS: 1) "MS" is the abbreviation for "manuscript".

23 Aug. [1914?]

My dear & blessed E.M.,

(I wish you had a name. Why do you always hide behind initials? What do your friends call you? My name is Edward, or ‘chips’!)

I have read your ‘Maurice’ after all, and am very much pleased with it. I don’t always like your rather hesitating tantalizing impressionist style - though it has subtleties - but I think the story has many fine points. You succeed in joining the atmosphere with the various characters, and there are plenty of happenings which is a good thing. Maurice’s love affairs are all interesting, and I have a mind to read them again, if I can find time - so I won’t send the MS back for a day or two. I am so glad you end up on a major chord. I was so afraid you were going to let Scudder go at the last - but you saved him and saved the story, because the end though improbable is not impossible and is the one bit of real romance - which those who understand will love.

I wish I could write more, but I am devoured just now by innumerable things. I expect to be in and about London from the 1st to 8th Sep. - so give me a cue to see you.

Your Edward C.

Transcription of vertical writings on the second page of the letter:

I am sending my birthday reply to the papers on Sep. 1 with a lot about the war in it.

Only a small part of the letter has been transcribed then included in reviews, or different Maurice editions. Which is why I wanted to transcribe the whole response from the real-life Maurice to the author of fictional Maurice after he read Maurice. The entirety is far more interesting.

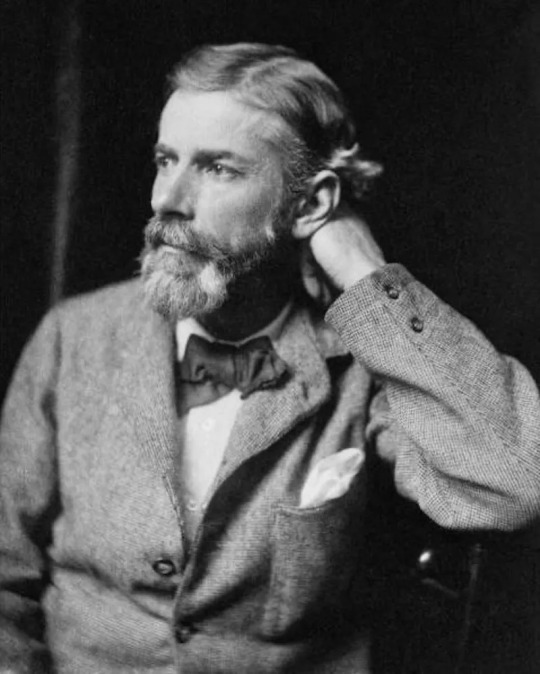

Below: Edward Carpenter in 1886 and 1897.

Some contexts: based on Forster's diaries, Maurice was first finished in June/July, 1914, so Carpenter did read the first complete MS—with or without the epilogue is unclear since there's no solid proof for when the epilogue was written (though it appeared in the novel by February 1915 at the latest.)

However, since Carpenter said he liked the happy ending he read (and fun fact: the first complete MS which he read actually had a fairly different ending between Maurice and Alec than the published version's), we know that even from the first draft, Forster remained unwavering about how a happy ending is imperative.

More contexts: according to a letter from Forster to a friend, he thought Carpenter was "too unliterary to be helpful"—meaning Carpenter probably wasn't much interested in reading literature. And Carpenter sort of confirmed that in writing "I read your 'Maurice' after all", implying he was indeed reluctant to read at first.

Still, it made absolute sense for Forster to send the story back to the man who, in a manner of speaking, held the copyright of Maurice in flesh before Forster even finished it.

So the question is: did Carpenter know that Maurice was inspired by him and his lover George Merrill? Did he know that he was the real-life Maurice and Merrill was the real-life Alec? Perhaps that was why he was reluctant to read the novel at first?

767 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Yet simply steering clear of prostitutes and lower-class establishments was not enough to satisfy the requirements of transvestite respectability; one also had to conform to dominant standards of dress and self-presentation:

"When we demand that the public acknowledge us, then we have the duty to dress and conduct ourselves publicly in an inconspicuous manner. ... At home each person can do as they choose and as they consider right, but in public they must conform"

There were, of course, important practical reasons for such a judgmental approach for successful "passing" represented an effective means of protection against physical and verbal harassment or arrest, as the following commentator acknowledged: This required both passing the test of gender authenticity, and meeting the demands of contemporary, unadorned bourgeois fashion: "The simplest dress is, in our case, often the most elegant." Middle-class transvestite commentators bluntly rejected any clothing or accessories they considered excessively opulent, gaudy, or dated, such as corsets, costume rings, or oversized earrings, even as such fashions continued to be favored by female impersonators and entertainers. Such attitudes amounted to a policing of one's cross-dressing peers based on the ability to "pass" in public as a respectable middle-class lady (female-to-male transvestites, on the other hand, were generally considered able to fly under the radar of the 'masculinized' female fashion so prominent in mid-1920s)."

"As hard as it is for us to suppress our instinct, I nonetheless advise all transvestites to only allow themselves to be seen in the clothing of the other sex when they are utterly certain that they will come into conflict with neither the police nor the broader public".

What I consider to be the origins of 'passing', from an excerpt of a study of middle class transvestites in Weimar Germany by Katie Sutton.

"'We Too Deserve a Place in the Sun': The Politics of Transvestite Identity in Weimar Germany" Katie Sutton, German Studies Review, Vol. 35, No. 2 (May 2012), pp. 335-354 https://www.jstor.org/stable/23269669 .

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Yet simply steering clear of prostitutes and lower-class establishments was not enough to satisfy the requirements of transvestite respectability; one also had to conform to dominant standards of dress and self-presentation:

"When we demand that the public acknowledge us, then we have the duty to dress and conduct ourselves publicly in an inconspicuous manner. ... At home each person can do as they choose and as they consider right, but in public they must conform"

There were, of course, important practical reasons for such a judgmental approach for successful "passing" represented an effective means of protection against physical and verbal harassment or arrest, as the following commentator acknowledged: This required both passing the test of gender authenticity, and meeting the demands of contemporary, unadorned bourgeois fashion: "The simplest dress is, in our case, often the most elegant." Middle-class transvestite commentators bluntly rejected any clothing or accessories they considered excessively opulent, gaudy, or dated, such as corsets, costume rings, or oversized earrings, even as such fashions continued to be favored by female impersonators and entertainers. Such attitudes amounted to a policing of one's cross-dressing peers based on the ability to "pass" in public as a respectable middle-class lady (female-to-male transvestites, on the other hand, were generally considered able to fly under the radar of the 'masculinized' female fashion so prominent in mid-1920s)."

"As hard as it is for us to suppress our instinct, I nonetheless advise all transvestites to only allow themselves to be seen in the clothing of the other sex when they are utterly certain that they will come into conflict with neither the police nor the broader public".

What I consider to be the origins of 'passing', from an excerpt of a study of middle class transvestites in Weimar Germany by Katie Sutton.

"'We Too Deserve a Place in the Sun': The Politics of Transvestite Identity in Weimar Germany" Katie Sutton, German Studies Review, Vol. 35, No. 2 (May 2012), pp. 335-354 https://www.jstor.org/stable/23269669 .

26 notes

·

View notes

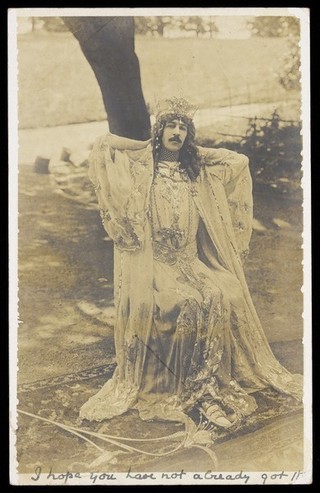

Photo

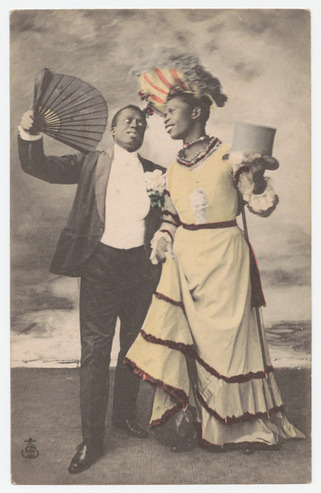

This extensive collection of postcards is housed in the Wellcome Library in London, UK. The postcards were originally collected by social historian James Gardiner and depict an array of drag experiences throughout the twentieth century. The earliest postcards capture moments of military and navy soldiers and prisoners of war during WWI. Later photographs, like those from the 1960s, portray familiar scenes from bars like Club 82, a prominent drag bar in New York at the time.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

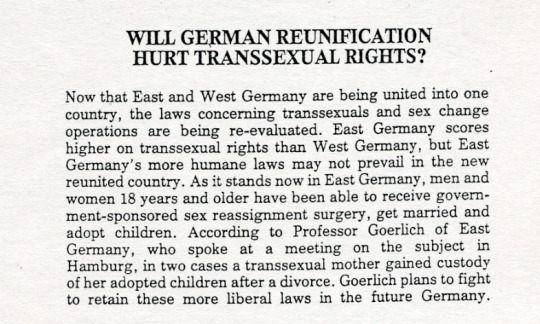

FTM Newsletter, Issue 12, June 1990, Written by Christian CB David, Edited by Lou Sullivan. Page 3.

780 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vera "Jack" Holme

Born in Lancashire, England, in 1881, Holme was an actor and activist. Holme cross-dressed as part of her music hall performances, taking on the name "Jack." She was part of the British suffragette movement and was a chauffeur for the Pankhursts. Holme was arrested for her political protesting for votes for women and spent time in Holloway prison.

0 notes

Text

Fanny and Stella

In 1870, Mrs Fanny Graham and Miss Stella Boulton, also known as Frederick William Park and Thomas Ernest Boulton, were prosecuted in London, England for committing buggery and conspiring to induce others to commit buggery. Though there was no English law against "cross-dressing," they were also prosecuted for outraging public decency by wearing women's clothes. Fanny and Stella were acquitted of the charges, but their prosecution signalled that defiance of gender norms could result in police surveillance and arrest.

0 notes

Text

youtube

Male impersonator and music hall performer Ella Shields.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anders Als Die Andern (Different From the Others)

'Anders Als Die Andern' is a German silent film released in 1919. The German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld was one of the co-writers of the film (he also made an appearance), with the plot focusing on a man being blackmailed for his homosexuality. At the time the film was released, homosexuality was criminalised in Germany under Paragraph 175. The film's sympathetic portrayal of homosexuality encouraged criticism of this law. However, new censorship laws were introduced in Germany in May 1920, and 'Anders Als Die Andern' was withdrawn in August 1920.

For more see Sara Friedman's post here: https://jhiblog.org/2019/05/28/projecting-fears-and-hopes-the-1919-anders-als-die-andern-controversy/

2 notes

·

View notes

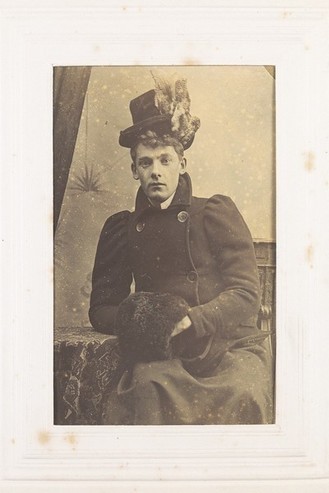

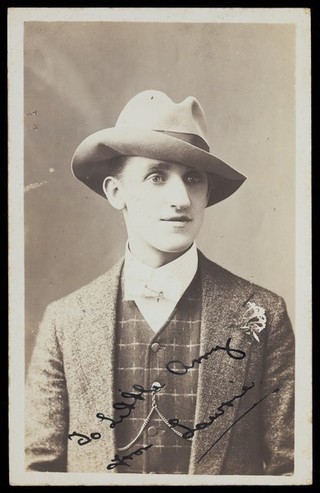

Photo

This collection of postcards of female and male impersonators and cross-dressing in Europe and the United States, 1900-1931, 1955 features copies of original postcards held by Cornell’s Human Sexuality Collection, part of Cornell Library’s Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections.

4K notes

·

View notes