Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Mid-Century Civic Architecture of Latin America

Post World War II, there was a large need for civic architecture in Latin America due to the poor state of the economy. There was unprecedented public housing construction as a result. The principles of modernism that include paying attention to the people’s social needs also encouraged this large boom of civic architecture, which became a solution for education and mass housing. It is important to create civic architecture because it is how the government can help the people that they rule. When there is architecture that meets the needs of the people like public housing, education buildings and business complexes, the economy of the country increases and gives the people more reasons to work hard for the betterment of the country. It can also give a sense of national pride and unity.

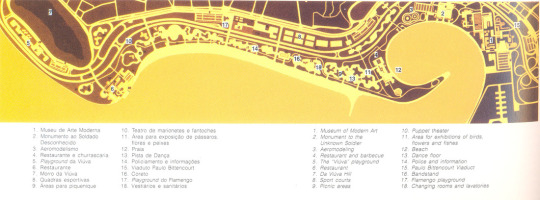

Plan of Parque do Flamengo

The Parque do Flamego, created in 1965, is a civic architecture and landscaping project that is of economic, recreational, and cultural importance to the city of Rio de Janiero, Brazil. It is an urban public park and recreation area about 2 kilometers long with an area of 296 acres near the opening of Guanabara Bay, with sports activities, restaurants, a public marina, airport, and expositions and museums (Ceniquel). It stands on what was previously Saint Antonio Hill, and built on “land reclaimed from the ocean,” and occupies the land between the highway and the beach (Carranza and Lara). The design of the park involved Roberto Burle Marx, who is one of Brazil’s greatest landscape architects due to the artistic way he designed parks and gardens, which is an abstract style of curvilinear and rectilinear blocks of color.

Aerial of the Marina at Parquo de Flamengo

The park is enhanced by the diverse use of Brazilian flora and use of native species. These trees and shrubs beautifully frame the ocean as you walk through the park. Even though the park is separate from the city because of the highway, it is easily accessible because of Marx’s design where the promenade is just as important as the landscape. Marx made sure to design the park in a way that vehicular and pedestrian traffic could both exist, where there are “walkways with gentle curves on freeways and underpasses,” clearly seen in the photograph above (Ceniquel).

Sources

Ceniquel, Mario. “Parque Do Aterro Do Flamengo.” Project for Public Spaces, March 24, 2006. https://www.pps.org/places/parque-do-aterro-do-flamengo.

Carranza, Luis E, and Fernando Luiz Lara. Modern Architecture in Latin America: Art. Austin, TX: University of Texas at Austin, 2015.

0 notes

Text

19th Century Urbanism

Latin America looked towards France, London, and Italy for their reinvention and transformation after fighting for independence from Spain and wanted to renounce their colonial roots. An extremely influential model is Paris, where Napoleon and Haussmann tore down many buildings to create large boulevards and grand public parks. Diagonals that break up the established city grid were also implemented, as seen in Mexico City and Buenos Aires, influenced by Christopher Wren’s plan for London. Many new building typologies were also introduced as a result of cosmopolitanism and industrialization, such as train stations, banks, and theatres and opera houses. These new building typologies were usually built in the form of neoclassicism, as a result of the Beaux-Arts school being the West’s most prestigious architecture school.

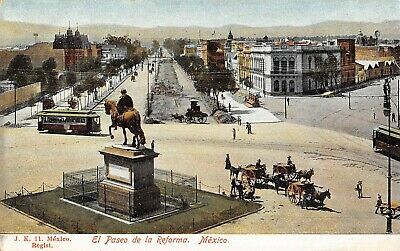

Reforma Avenue, 1904

Mexico City’s Reforma Avenue is one of the first examples where a Parisian boulevard is seen in Latin America and connects downtown Mexico City with the largest urban park in Latin America, Chapultepec. Reforma Avenue has four plazas along its route with monuments and extensive plantings and pedestrian promenades. The Palace of Fine Arts by Adamo Baori in Mexico City was also constructed in the style of Neoclassicism, and clearly inspired by Garnier’s Opera House in Paris and La Scala in Milan. Neighborhoods like Colonia Roma began being built by the wealthy for an escape from the city. Most of the houses built in Roma were also built in European architecture styles with French, Roman, Gothic and Moorish elements.

Teatro Colon

Following a similar path as Mexico City, Buenos Aires also transformed their city to become more modern through the construction of Parisian boulevards like Avenido de Mayo to Neoclassical government buildings. For example, Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires, stylistically looks like a Greek Temple. It was a sign of how Buenos Aires wanted to become another Paris, and how countries in Latin America were no longer looking towards Spain, rather, they were looking towards Paris.

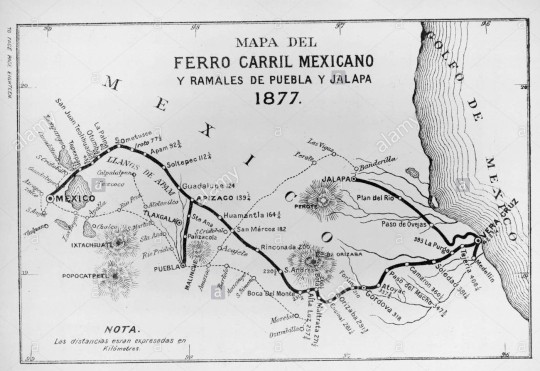

Mexico’s first railroad from Mexico City to Veracruz

Industrialization played a large part in the expansion and modernization of colonial cities like Mexico City and Buenos Aires because it was included in government’s plan to keep up with the rest of the world. As a result, many railways were built and streetcars were built, which facilitated the creation of new neighborhoods for the working class. This also played a part in how the government was trying lure immigrants to their respective countries.

Sources

https://www.britannica.com/art/Latin-American-architecture/Postindependence-c-1810-the-present

Cardinal-Pett, Clare. A History of Architecture and Urbanism in the Americas. New York, NY: Routledge, 2016.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Latin American Colonial Urbanism

Colonial Latin American societies reflected the imposition of European, more specifically Spanish, standards and ideals on existing Latin American civilizations. This is shown through the paintings of the casta, the class order, and creation of plazas and a rigid grid system.

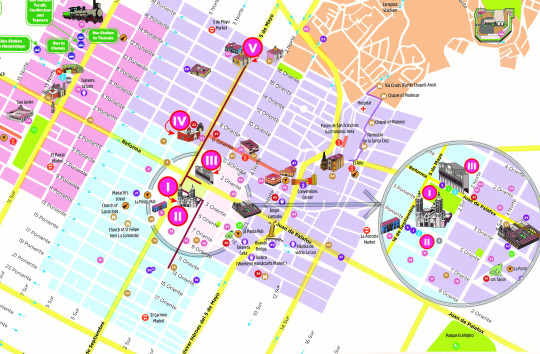

Map of Puebla City’s Historic District

When the first Viceroyalty of New Spain, Mexico City, was established in 1535, the Spaniards implemented a grid to “order” the city. This is also seen in the city of Puebla. Puebla is located about two hours southeast of Mexico City. Here, block sizes measured 100 by 200 yards, with the longer side lying on the east-west axis (Kubler, 161). Puebla’s main square, Zocalo, has a great open space about the size of one block and is surrounded by a cathedral and the city hall. This is a testament to Spanish ideals because of the emphasis of religion at the center of the city with the government building right next to it. The plaza is also a reflection of European notions, where open space is considered precious.

Puebla’s Cathedral and Zocalo

The relations between religion and government is also reflected in the class order, along with where people live in the city. Spaniards and religious (Catholic) figures were more likely to live near the main square whereas the indigenous people would live farther away and across the river in Puebla. There was a distinct separation between the two groups, which can also be seen in Mexico City, “where the unplanned, impermanently-house Indian groups were assigned to the western and northern edges of the European colony” (Kubler, 162).

Casta paintings by Francisco Clapera

Racial order in New Spain is also illustrated in casta paintings, which are paintings that describe hierarchy as a result of “racial mixing.” The hierarchy was established as a result of the Spaniards’ anxiety about racial mixing and to help make sense of it; it was directly proportional to the amount of Spanish blood in each of the racial groups (Ruffin). At the top of the hierarchy is, of course, the Spanish-born immigrants and creoles (a person of Spanish descent born in the Americas). In middle, there were people of mixed blood; those with the most Spanish blood at the top of the middle class (castizo, mestizo, etc.) and those with the least Spanish blood in the lower. At the bottom of the hierarchy were the 100% indigenous and blacks.

In conclusion, racial order and implementation of Spanish ideals in New Spain is one of the many instances of old world order that still exist and is evident today. Many people from the countries that used to be colonized still practice Catholicism, though many may have separated religion from their government systems. Social hierarchy is also still relevant to the present, as the indigenous and African-Americans are continuously treated poorly by the government, though it seems to be getting better (“Indigenous Latin America in the Twenty-First Century”).

Works Cited

“Indigenous Latin America in the Twenty-First Century.” World Bank. World Bank, March 12, 2018. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/lac/brief/indigenous-latin-america-in-the-twenty-first-century-brief-report-page.

Kubler, George. "Mexican Urbanism in the Sixteenth Century." The Art Bulletin 24, no. 2 (1942): 160-71. Accessed June 9, 2020. doi:10.2307/3046816.

Ruffin, Herbert G. “Sistema De Castas (1500s-Ca. 1829) •.” BlackPast. BlackPast, October 17, 2019. https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/sistema-de-castas-1500s-ca-1829/.

0 notes

Text

Pre-Columbian Architecture & Urbanism

Pre-columbian civilizations were complex and sophisticated even before European arrival. The Aztecs, Teotihuacan, and the Inkas are similar in that religion plays a huge role, which can be seen in their architecture and their urban planning, as religious structures were placed in the center of their cities and were the largest. It’s incredible how they created grand structures and cities without the use of metal tools. There is also a similar structure in residential units where there is housing around a central courtyard.

Teotihuacan

View of Pyramid of the Moon from the Pyramid of the Sun

Teotihuacan is an ancient city in Mesoamerica that existed from 100 BC to 650 AD, just north of present-day Mexico City. Today, it is known as the City of the Gods, a title given by the Aztec Civilization when they discovered it centuries later. Although little is known about the people who built it, archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians have discovered a lot from excavations and analysis of the city’s remains. From decades of research, it was found that the city had a grid pattern; in the “downtown” area, there is had a long and wide avenue called the “Street of the Dead” that connected the cultural and religious infrastructure such as the Pyramids of the Moon and of the Sun. The structures indicated obvious attention to design through deliberate planning and clear mathematical and geometrical order.

Aztec Tenochtitlan

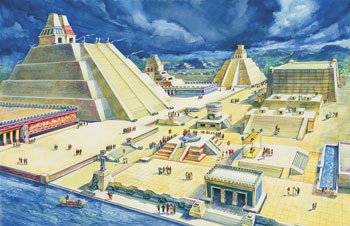

Main Plaza of Tenochtitlan

Tenochtitlan is the capital of the Aztecs, which was settled in 1325. It existed in the middle of a system of five lakes in the Valley of Mexico. Due to the city being in a lake, the Aztecs built chinampas, which are artificial islands, used for farming and also the foundation of the city. This established a grid and canals as a means to travel through the city. Tenochtitlan only had four roadways leading to the city from the mainland, which divided the city into neighborhoods. The Aztecs’ religion heavily influenced their daily lives and architecture, performing daily sacrificial acts. They believed that the larger structures brought them closer to their gods, which is evident in the grand scale of the Aztecs’ temples.

Inca

Aerial of present-day Cuzco

The capital of the Inkan civilization is Cuzco, which means “navel of the world” in Quechua. The Incans are known for their masonry architecture and built without mortar. Stone was a readily available resource and was considered a sacred material. An example is Qurikancha, a sacred Inca temple dedicated worship of the sun and located at the center point of the empire, which had curved ashlar stonework that had blocks of stone cut into rectangles and then stacked. This temple is also the center point of the empire. The Incas also had residential blocks called “canchas” that consisted of small courtyards surrounded by small pavilions.

0 notes