Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I’ve seen the Ursula K LeGuin quote about capitalism going around, but to really appreciate it you have to know the context.

The year is 2014. She has been given a lifetime achievement award from the National Book Awards. Neil Gaiman puts it on her neck in front of a crowd of booksellers who bankrolled the event, and it’s time to make a standard “thank you for this award, insert story here, something about diversity, blah blah blah” speech. She starts off doing just that, thanking her friends and fellow authors. All is well.

Then this old lady from Oregon looks her audience of executives dead in the eye, and says “Developing written material to suit sales strategies in order to maximize corporate profit and advertising revenue is not the same thing as responsible book publishing or authorship.”

She rails against the reduction of her art to a commodity produced only for profit. She denounces publishers who overcharge libraries for their products and censor writers in favor of something “more profitable”. She specifically denounces Amazon and its business practices, knowing full well that her audience is filled with Amazon employees. And to cap it off, she warns them: “We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.”

Ursula K LeGuin got up in front of an audience of some of the most powerful people in publishing, was expected to give a trite and politically safe argument about literature, and instead told them directly “Your empire will fall. And I will help it along.”

131K notes

·

View notes

Text

Piss, Bread and Circuses

Hello again. I recently visited the Australian Film, Television and Radio School for their latest Re:Frame event, which was about audience engagement in the attention economy. After just ten minutes, I wanted to stab my eyes with a pencil.

Station ident: After returning to design after a year away, I find that Everything Now Looks Very Strange Indeed™. This is another one of my updates on restarting a creative practice (which I’m calling Studio Thing), plus a dose of cultural and design commentary.

Ah yes, the eye-stabbing. I can imagine many interesting conversations about attention in a post-broadcast media world, but when this event opened with a keynote from self-proclaimed “Data Whisperer” Elisa Choy, they were almost occluded in advance. Choy’s talk represented everything that might be dubious about the meeting of Big Data and creative strategy: figuring her audience as a bunch of panicked TV executives, she opined about the declining ratings of big tentpole shows like MasterChef. As a panacea for this non-problem, Choy offered her data-whispering “methodology”: ambulance-chasing the public’s roiling opinions on social media, which we can then mirror by creating the Right Content™. Pet-swapping is hot, so we should make shows about pet-swapping! I kid you fucking not.

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

The death spiral of bread and circuses[/caption]

Look, I know, feedback loops have the potential to enable many things, but they’re not necessarily positive, and here I have to take a stand: this particularly impoverished approach to data and culture represents the tightening of a noose around society’s neck. Rather than opening up possibilities in cultural production, the weaponisation of social media metrics to slavishly create What the Public Wants only serves to narrow our focus to that of a cybernetic Id: the collective embodiment of the prototypical addict, reduced to drinking their own toxic urine from a tube. (Having myself sought professional help over poisonous feedback loops involving substances that amongst other things included, uh, Netflix, I don’t use such metaphors lightly.)

Of course, I’d merely shrug if such an approach weren’t already so sadly emblematic of where we’re at as a society. The dream of a perfectly closed loop of reactive idiocy won’t ever fully “work”, of course, but in this era of insta-populism and habit-forming media apparatuses that feed on our own bile, we’re nonetheless currently living the damage wreaked by such attempts. As strategists, designers and producers of culture, we should be doing everything we can to avoid this spiral into doom.

Georgia Rowe, a service designer at the ABC, slyly mentioned at the same event that being sensitive to the breadth of people’s lived contexts would be, you know, essential to any kind of useful loop of engagement. Her respect for that universe of possibility within the pores of everyday life, rather than its reduction into more yet grist for the mill, has always been the progressive horizon of Human-Centred Design. But I’m not sure that this is enough to counterbalance the spectre before us: media landlords, populist strongmen and other disreputables, busily instrumentalising our data into some kind of zombie-reptilian autonomic nervous system of anti-culture. And it’s not Georgia’s individual responsibility to create a stronger antidote to such tendencies, either; shouldn’t we collectively be pushing harder in other directions?

In fact, I wonder these days if the “human context” we so often highlight has become a fig-leaf or alibi for our underlying zombie-reptile tendencies. Is the very popularisation of Human-Centred Design in the current juncture, which correlates so strongly with the rise of our current digital product overlords, itself a symptom of our predicament? As someone who cut their teeth as a Director of Design at Australia’s first social-purpose-focused Human-Centred Design studio, it’s not easy for me to say this, but our obsessive focus on fashioning usable, desirable products, and thus the methods we use to do this — including HCD — are imbricated in this short-circuit of desire, and exploited by the profiteers of our attention. Perhaps some spanners need to be thrown into the works, lest design is sucked into its own black hole.

Beneath the pavement: the rave

The second keynote at Re:Frame was from Seb Chan, the Chief Experience Officer at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image. Seb’s work is thankfully all about creating the conditions for reigniting curiosity and community, rather than death-spiralling. (He’s also an exemplary citizen of the Republic of Newsletters; Fresh and New is essential reading for anyone interested in culture and technology, as well as having an interesting “pay to access the archives” business model. Go and subscribe, immediately. Seb’s also responsible for giving me the kick in the pants to post a new issue: “I like your newsletter,” he told me after his talk as I blushed prettily, “… WHEN IT COMES OUT.” Ahem.)

Seb said a couple of slightly cryptic but suggestive things in his keynote that I think can help loosen design’s tendency to auto-asphyxiate under capitalism. Firstly, he noted that his design approach isn’t focused on reactively addressing “user needs”. (And he was also clear that neither is it about narrowly focusing on transactional interactions, as experience design so often is.) Secondly, he acknowledged that his current work in experience design inevitably draws from his background in organising electronic dance parties in the distant 20th Century — a different but related kind of “experience”. (No doubt some of you also remember going to Frigid in ‘90s Sydney. Good times!) Moreover, he provocatively described those events as “utopian, elite and exclusionary”.

It might be surprising to hear a senior figure of a public cultural institution use terms that could be interpreted as “anti-democratic”, but that’s not really the angle here. Seb’s approach certainly isn’t about disregarding the needs of ACMI’s visitors, or making it the sole preserve of over-educated latté-belters. Rather, going beyond “user needs” opens up possibilities that would be foreclosed by seeing visitors as simply customers who need to be mechanically serviced. And by being underground, 20th Century electronic dance culture created pockets of safety that enabled sexual minorities to have space to flourish, outside the panopticon of the dominant culture. Subcultures therefore serve as an alternative model for conceiving of how we might experience public institutions and infrastructures. The upshot is not how to make museums more obscure, but how we can use this insight to create spaces of conviviality across our social terrain.

In a recent newsletter, Seb put it this way:

When people in the cultural sector talk about museums or libraries as aiming to become ‘town squares’ or similar, I wonder if they are missing a trick. A town square is where only the loudest voices can be heard. Perhaps a town square is not what is needed, but an ecology of smaller niches where smaller voices thrive? And the institutional role lies in being a facilitator of the connections between niches?

Essentially, this is about a different way to be public.

Beneath the pavement: limestone caves

Thinking about this thought-bomb, I’m reminded of nothing less than W.H. Auden’s magnificent 1948 poem “In Praise of Limestone”, which contrasts the gentle affordances of limestone caves with other, less forgiving geological spaces:

“Come!" purred the clays and gravels,

“On our plains there is room for armies to drill; rivers

Wait to be tamed and slaves to construct you a tomb

In the grand manner: soft as the earth is mankind and both

Need to be altered."

Against a totalising, scorched-earth concept of public space, Auden yearns for his sensual pockets of limestone. He’s not uncritical — like anybody who’s grappled with the limits of the identity politics that sometimes come with subcultural niches, the poem is ambivalent about the indulgence and narcissism that such spaces can engender, but it’s suggestive of something much more interesting to me than the flattened, data-whispered zombie dystopia of The Public (Opinion) that appears to be all the rage these days.

More on publics and counterpublics next week! I’m currently in Melbourne for the sometimes-provocative SDNOW conference, and there’s too much to write about…

A sustainable portion of all my love,

Ben

0 notes

Text

Death and Revival Revisited

The End is the Beginning is the End, as Billy Corgan suggests on the soundtrack to (what I feel is the unjustly maligned) Batman Forever. I had way too much “decline and rebirth” material to fit in the last issue, so I'll continue to follow that seam for a while. (You'll find that downturn and revival is a recurring, uh, theme here at Recurring Thing.)

After returning to design after a year away, I find that Everything Now Looks Very Strange Indeed™. This is another one of my updates on restarting a creative practice (which I’m calling Studio Thing), plus a dose of cultural and design commentary.

(If someone’s forwarded this thing to you in the hope you’ll find it interesting, you can subscribe here to secure my everlasting love. And please, pass it on if you think it might be of interest to anyone.)

🔂🧟♀️ The eternal return of zombie-centred design

Some follow-up on that evergreen topic of what comes after human-centred design: at TEDxSydney I delightedly crossed paths with fellow innovation veteran Carli Leimbach, who’s been thinking about “earth-centred design” as a corrective to anthropocentrism. I’m intrigued. She’s run an initial workshop with some like-minded people, and I’ll keep tabs on her progress.

In other more-than-human news, Anne Galloway recently posted her talk at IndiaHCI 2018, “Designing with, and for, the more-than human”. I’ve been following Anne’s work for a long time, from when the Internet of Things was called “pervasive computing”, to her more recent work in Aotearoa about sheep. For Anne, more-than-human-centred design means:

“Acknowledging that human beings are not the be-all and end-all.”

“Accepting our vulnerability, acting with humility and valuing our interdependency.”

“Living with the world, not against it.”

Recommended. Also interesting is the “more-than-human design research roll-call” she recently initiated on Twitter. Follow this link if you want to get in touch with people who are active on the topic, at least in academic circles — some familiar names pop up.

🥪🤮 The alternative to curiosity is… hard to swallow

I’ve just wrapped up my NEIS coursework, and to celebrate I want to recount a story about my teacher Jason that also demonstrates why I’m so glad I decided to sign up for this microbusiness training and mentoring program.

A few years ago, Jason was the director of training at a large catering company which had a significant focus on healthcare facilities such as nursing homes. To get a feel for the training needs of his workforce, he decided to tour their workplaces, immersing himself in their day-to-day work. (His CEO was frankly a little surprised by this — as is the case with many sectors, it was uncommon for management to visit the frontlines. In fact, when he urged the Head of Care at one aged care facility to tour the frontlines of her own operation with him, the staff didn't recognise her, and assumed she was a visitor. Yikes.)

While working with kitchen staff in one nursing home, Jason noticed that one resident, a lone old woman, always ordered the same dish: a single salmon sandwich. Intrigued, he asked the staff about this, and they shrugged. “She must like it,” was the reply.

The next day, Jason decided to have lunch with her. After a pleasant meal together, he couldn't contain himself.

“Betty, I've noticed that you always order a salmon sandwich,” he said. (I love that he still remembers her name.) “I don't mean to pry, but, uh, why is that?”

She looked at him for a second.

“It's because I'm afraid,” Betty whispered.

It turned out that Betty had dysphagia — a problem with her pharynx or oesophagus that made swallowing difficult — and was terrified that if she admitted this, she would be placed on the puréed diet of an invalid. Over time, she'd gotten used to salmon sandwiches as the one meal she knew could swallow without issue. And because of her fears, that's all she ate.

“Betty, how long have you been eating salmon sandwiches as your only meal?” Jason asked.

“Two years.” So basically, a resident had been potentially malnourishing herself for years because the systems around providing and talking about choices under this regime of care were broken.

After setting her up with a more appropriate (and still chewable) set of diet choices, Jason decided to consult with dysphagia experts and patients like Betty to create a unit of training about these kinds of patient needs, aimed at preventing such system breakdowns. Everyone at their client nursing homes could attend. The aged-care nurses who came were flummoxed, telling their Head of Care, “Why are we only hearing about these kinds of problems and solutions from the catering guy? No offence, Jason, but seriously, WTF?”

In the midst of such regimented systems, where industrial efficiency often erases the possibility of supple action or even humane behaviour, I’m grateful that compassionate minds like Jason’s exist. When curiosity seems like it's at death’s door, people like him arrive to revive it.

The reveal: I was initially pretty skeptical about doing the course under Jason because before classes started, I'd gleaned that he’d spent most of his career managing McDonald’s restaurants. It turns out that my fears were misplaced, because I got a lot out of his teaching. While I really don't share his interest in large food systems, either in experiencing them as a customer nor in their general industrial impact on the world, I'm glad there are people like him enmeshed in such forbidding places, trying to make them more sensitive, responsive and just.

👹👽 First and Last Men

When’s the right time to write a requiem for the human species?

The other night I had the pleasure of experiencing the late Jóhann Jóhannsson’s First and Last Men, a live symphonic and film adaptation of Olaf Stapledon’s seminal 1930 sf novel of future history, narrated by that alien god who lives among us, Tilda Swinton.

(I only knew the Stapledon novel by reputation, and Jóhannsson from his film scores, but was recently prodded to see this production when I watched Philip Kaufmann’s excellent 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. In a passing exchange that you’d easily miss, two characters chat about their reading habits, and Stapledon’s work is mentioned. More on this later. Intrigued, I pounced on the Jóhannsson version when it arrived in Sydney as part of the Vivid Festival.)

Jóhannsson only uses the last part of Stapledon’s immense story, which starts in the 20th Century and spans the next two billion years. This focus on the last of eighteen successive human species summons a particularly elegiac mood. Responding to the eventual extinction of life on Earth, humans have genetically re-engineered themselves for life on Neptune, and it is these highly advanced Neptunian humans, astonishing in their animalistic diversity, 20-year pregnancies and 2000-year childhoods, for whom Swinton speaks with such characteristically icy dignity. (My god: that voice.)

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

As the camera slowly pans across a series of Yugoslavian Stalinist monuments (you probably know the ones — they recently came into vogue online in the last wave of ruin porn), we cycle through glassy sheets of what anticipatory mourning sounds like: slow arpeggios, and vocals that alternate between the wonderful anonymity of wind instruments and the mewling of cats. (I want to celebrate the two vocalists precisely because they didn’t call attention to themselves: they were exemplary orchestral players.)

The mood is well-earned: despite all the ingenuity and adaptability of these far-future humans, we discover that a cascade of supernovas has triggered our final extinction. Manned interstellar spaceflight — that mainstay of most sf — is revealed as madness, reducing humans at their technological, technological and ethical peak to nihilistic despair. And as the ever-warming climate of Neptune slowly wreaks havoc on their awesome civilisation, the only thing these “Last Men” can do is make telepathic contact with the past — the conceit that enables Tilda Swinton to narrate the tale for us — as they wait for the end.

It’s uncanny how much this story from 1930 resonates with our slowly unfolding climate change disaster. And now that the worst seems inevitable, the intense melancholy of Jóhannsson’s First and Last Men feels fitting — a necessary alternative to either denial or relentless panic. But beyond this, I’m impressed by the supreme ambivalence of Jóhannsson’s take. He makes the Last Men as dignified and magisterial as they are aloof, and their vaunted supremacy is a mixture of authentic maturity and our own sneaking suspicion that in their immortal, genetically-designed perfection, these final humans have lost the capacity to take unexpected action. It’s profoundly sympathetic.

This suggests to me that having a post-human-centred design orientation is very far from being misanthropic. Perhaps we just need to stop pretending that empathy is ever completely possible — who can truly pretend to empathise with a post-human species two billion years in the future, let alone our strange and often unknowable fellow lifeforms, be they vertebrate, invertebrate or botanical? — and instead extend a generalised (and non-paternalistic) sympathy to our neighbours and ourselves. Sympathy is okay. Yes, our situation can be pegged to a combination of pathetic ignorance, shortsighted greed and genuine moustache-twirling villainy. And we are not the centre of the universe. But like others, we are still a species that deserves a dignified mourning.

🦸🏼♂️☄️ Can only a God save us now?

Stapledon’s 1930s future-superhumans continue to haunt me.

When I was teaching art to six-year-olds last year, I did a unit on comics, tracing the emergence of costumed superheroes to the ’30s.

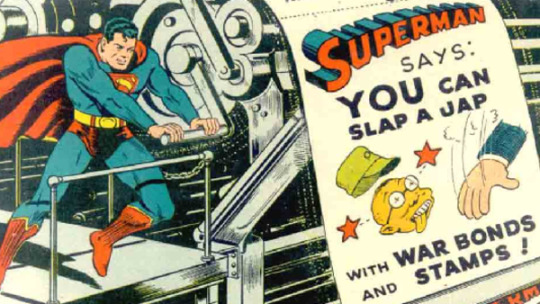

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

No comment.[/caption]

“Why do you think superheroes appeared then?” I asked the class. “What was going on?”

“IT WAS IN THE MIDDLE OF THE WORLD WARS!” said one student. “MILLIONS OF PEOPLE WERE DYING!” called out another. “My great-grandmother met my great-grandfather in a Spanish flu hospital during World War I!” came another, very-relevant non-sequitur. (It’s easily forgotten that the 1918 influenza outbreak killed at least 50 million people. And yes, these kids are amazing, and publicly funded education is the fucking best.)

Out of the despair of modernity — mechanised mass slaughter and earth shattering pandemics enabled by the globalisation of capitalist industry — we cried out for salvation. Yes, there are many reactionary underpinnings to our superheroic imaginaries (the above image is just the most obvious), but their basis in real trauma behooves us to at least be sympathetic their emergence. We need to take fantasies of supermen seriously (and critically), rather than simply dismissing them as misguided or ridiculous because they’re rather obviously dodgy as fuck. And similarly, we need to take populism seriously.

Make no mistake: while I’m fascinated by downturn and revival narratives, they’re more often than not pretty terrifying: “Make America Great Again” is the clearest contemporary example. And when famed philosopher Martin Heidegger looked forward to “a spiritual renewal of life in its entirety,” he was talking about Adolf Hitler. Don’t look away. Stay and fight in the mud.

🚀🌎 Refuge

Besides talking to the past, the final act of desperation of the Last Men was to transmit proto-organic matter into space, designing it to reassemble on favourable ground in a direction towards intelligent life. (Listening to Tilda Swinton intone gravely about “the Great Dissemination” was just too deliciously weird.) Of course, this is the plot of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the story that prompted me to explore First and Last Men in the first place: we are being invaded by relentless pod-people, growing out of seeds assembled from “living threads that float on the stellar winds.”

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

Not just taking our jobs — they're stealing Jeff Goldblum's life![/caption]

Too delicious.

Yours in ambivalence,

Ben

0 notes

Text

Death and Revival Revisited

The End is the Beginning is the End, as Billy Corgan suggests on the soundtrack to (what I feel is the unjustly maligned) Batman Forever. I had way too much “decline and rebirth” material to fit in the last issue, so I'll continue to follow that seam for a while. (You'll find that downturn and revival is a recurring, uh, theme here at Recurring Thing.)

After returning to design after a year away, I find that Everything Now Looks Very Strange Indeed™. This is another one of my updates on restarting a creative practice (which I’m calling Studio Thing), plus a dose of cultural and design commentary.

(If someone’s forwarded this thing to you in the hope you’ll find it interesting, you can subscribe here to secure my everlasting love. And please, pass it on if you think it might be of interest to anyone.)

🔂🧟♀️ The eternal return of zombie-centred design

Some follow-up on that evergreen topic of what comes after human-centred design: at TEDxSydney I delightedly crossed paths with fellow innovation veteran Carli Leimbach, who’s been thinking about “earth-centred design” as a corrective to anthropocentrism. I’m intrigued. She’s run an initial workshop with some like-minded people, and I’ll keep tabs on her progress.

In other more-than-human news, Anne Galloway recently posted her talk at IndiaHCI 2018, “Designing with, and for, the more-than human”. I’ve been following Anne’s work for a long time, from when the Internet of Things was called “pervasive computing”, to her more recent work in Aotearoa about sheep. For Anne, more-than-human-centred design means:

“Acknowledging that human beings are not the be-all and end-all.”

“Accepting our vulnerability, acting with humility and valuing our interdependency.”

“Living with the world, not against it.”

Recommended. Also interesting is the “more-than-human design research roll-call” she recently initiated on Twitter. Follow this link if you want to get in touch with people who are active on the topic, at least in academic circles — some familiar names pop up.

🥪🤮 The alternative to curiosity is… hard to swallow

I’ve just wrapped up my NEIS coursework, and to celebrate I want to recount a story about my teacher Jason that also demonstrates why I’m so glad I decided to sign up for this microbusiness training and mentoring program.

A few years ago, Jason was the director of training at a large catering company which had a significant focus on healthcare facilities such as nursing homes. To get a feel for the training needs of his workforce, he decided to tour their workplaces, immersing himself in their day-to-day work. (His CEO was frankly a little surprised by this — as is the case with many sectors, it was uncommon for management to visit the frontlines. In fact, when he urged the Head of Care at one aged care facility to tour the frontlines of her own operation with him, the staff didn't recognise her, and assumed she was a visitor. Yikes.)

While working with kitchen staff in one nursing home, Jason noticed that one resident, a lone old woman, always ordered the same dish: a single salmon sandwich. Intrigued, he asked the staff about this, and they shrugged. “She must like it,” was the reply.

The next day, Jason decided to have lunch with her. After a pleasant meal together, he couldn't contain himself.

“Betty, I've noticed that you always order a salmon sandwich,” he said. (I love that he still remembers her name.) “I don't mean to pry, but, uh, why is that?”

She looked at him for a second.

“It's because I'm afraid,” Betty whispered.

It turned out that Betty had dysphagia — a problem with her pharynx or oesophagus that made swallowing difficult — and was terrified that if she admitted this, she would be placed on the puréed diet of an invalid. Over time, she'd gotten used to salmon sandwiches as the one meal she knew could swallow without issue. And because of her fears, that's all she ate.

“Betty, how long have you been eating salmon sandwiches as your only meal?” Jason asked.

“Two years.” So basically, a resident had been potentially malnourishing herself for years because the systems around providing and talking about choices under this regime of care were broken.

After setting her up with a more appropriate (and still chewable) set of diet choices, Jason decided to consult with dysphagia experts and patients like Betty to create a unit of training about these kinds of patient needs, aimed at preventing such system breakdowns. Everyone at their client nursing homes could attend. The aged-care nurses who came were flummoxed, telling their Head of Care, “Why are we only hearing about these kinds of problems and solutions from the catering guy? No offence, Jason, but seriously, WTF?”

In the midst of such regimented systems, where industrial efficiency often erases the possibility of supple action or even humane behaviour, I’m grateful that compassionate minds like Jason’s exist. When curiosity seems like it's at death’s door, people like him arrive to revive it.

The reveal: I was initially pretty skeptical about doing the course under Jason because before classes started, I'd gleaned that he’d spent most of his career managing McDonald’s restaurants. It turns out that my fears were misplaced, because I got a lot out of his teaching. While I really don't share his interest in large food systems, either in experiencing them as a customer nor in their general industrial impact on the world, I'm glad there are people like him enmeshed in such forbidding places, trying to make them more sensitive, responsive and just.

👹👽 First and Last Men

When’s the right time to write a requiem for the human species?

The other night I had the pleasure of experiencing the late Jóhann Jóhannsson’s First and Last Men, a live symphonic and film adaptation of Olaf Stapledon’s seminal 1930 sf novel of future history, narrated by that alien god who lives among us, Tilda Swinton.

(I only knew the Stapledon novel by reputation, and Jóhannsson from his film scores, but was recently prodded to see this production when I watched Philip Kaufmann’s excellent 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. In a passing exchange that you’d easily miss, two characters chat about their reading habits, and Stapledon’s work is mentioned. More on this later. Intrigued, I pounced on the Jóhannsson version when it arrived in Sydney as part of the Vivid Festival.)

Jóhannsson only uses the last part of Stapledon’s immense story, which starts in the 20th Century and spans the next two billion years. This focus on the last of eighteen successive human species summons a particularly elegiac mood. Responding to the eventual extinction of life on Earth, humans have genetically re-engineered themselves for life on Neptune, and it is these highly advanced Neptunian humans, astonishing in their animalistic diversity, 20-year pregnancies and 2000-year childhoods, for whom Swinton speaks with such characteristically icy dignity. (My god: that voice.)

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

As the camera slowly pans across a series of Yugoslavian Stalinist monuments (you probably know the ones — they recently came into vogue online in the last wave of ruin porn), we cycle through glassy sheets of what anticipatory mourning sounds like: slow arpeggios, and vocals that alternate between the wonderful anonymity of wind instruments and the mewling of cats. (I want to celebrate the two vocalists precisely because they didn’t call attention to themselves: they were exemplary orchestral players.)

The mood is well-earned: despite all the ingenuity and adaptability of these far-future humans, we discover that a cascade of supernovas has triggered our final extinction. Manned interstellar spaceflight — that mainstay of most sf — is revealed as madness, reducing humans at their technological, technological and ethical peak to nihilistic despair. And as the ever-warming climate of Neptune slowly wreaks havoc on their awesome civilisation, the only thing these “Last Men” can do is make telepathic contact with the past — the conceit that enables Tilda Swinton to narrate the tale for us — as they wait for the end.

It’s uncanny how much this story from 1930 resonates with our slowly unfolding climate change disaster. And now that the worst seems inevitable, the intense melancholy of Jóhannsson’s First and Last Men feels fitting — a necessary alternative to either denial or relentless panic. But beyond this, I’m impressed by the supreme ambivalence of Jóhannsson’s take. He makes the Last Men as dignified and magisterial as they are aloof, and their vaunted supremacy is a mixture of authentic maturity and our own sneaking suspicion that in their immortal, genetically-designed perfection, these final humans have lost the capacity to take unexpected action. It’s profoundly sympathetic.

This suggests to me that having a post-human-centred design orientation is very far from being misanthropic. Perhaps we just need to stop pretending that empathy is ever completely possible — who can truly pretend to empathise with a post-human species two billion years in the future, let alone our strange and often unknowable fellow lifeforms, be they vertebrate, invertebrate or botanical? — and instead extend a generalised (and non-paternalistic) sympathy to our neighbours and ourselves. Sympathy is okay. Yes, our situation can be pegged to a combination of pathetic ignorance, shortsighted greed and genuine moustache-twirling villainy. And we are not the centre of the universe. But like others, we are still a species that deserves a dignified mourning.

🦸🏼♂️☄️ Can only a God save us now?

Stapledon’s 1930s future-superhumans continue to haunt me.

When I was teaching art to six-year-olds last year, I did a unit on comics, tracing the emergence of costumed superheroes to the ’30s.

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

No comment.[/caption]

“Why do you think superheroes appeared then?” I asked the class. “What was going on?”

“IT WAS IN THE MIDDLE OF THE WORLD WARS!” said one student. “MILLIONS OF PEOPLE WERE DYING!” called out another. “My great-grandmother met my great-grandfather in a Spanish flu hospital during World War I!” came another, very-relevant non-sequitur. (It’s easily forgotten that the 1918 influenza outbreak killed at least 50 million people. And yes, these kids are amazing, and publicly funded education is the fucking best.)

Out of the despair of modernity — mechanised mass slaughter and earth shattering pandemics enabled by the globalisation of capitalist industry — we cried out for salvation. Yes, there are many reactionary underpinnings to our superheroic imaginaries (the above image is just the most obvious), but their basis in real trauma behooves us to at least be sympathetic their emergence. We need to take fantasies of supermen seriously (and critically), rather than simply dismissing them as misguided or ridiculous because they’re rather obviously dodgy as fuck. And similarly, we need to take populism seriously.

Make no mistake: while I’m fascinated by downturn and revival narratives, they’re more often than not pretty terrifying: “Make America Great Again” is the clearest contemporary example. And when famed philosopher Martin Heidegger looked forward to “a spiritual renewal of life in its entirety,” he was talking about Adolf Hitler. Don’t look away. Stay and fight in the mud.

🚀🌎 Refuge

Besides talking to the past, the final act of desperation of the Last Men was to transmit proto-organic matter into space, designing it to reassemble on favourable ground in a direction towards intelligent life. (Listening to Tilda Swinton intone gravely about “the Great Dissemination” was just too deliciously weird.) Of course, this is the plot of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the story that prompted me to explore First and Last Men in the first place: we are being invaded by relentless pod-people, growing out of seeds assembled from “living threads that float on the stellar winds.”

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

Not just taking our jobs — they're stealing Jeff Goldblum's life![/caption]

Too delicious.

Yours in ambivalence,

Ben

0 notes

Text

Death and Revival Revisited

The End is the Beginning is the End, as Billy Corgan suggests on the soundtrack to (what I feel is the unjustly maligned) Batman Forever. I had way too much “decline and rebirth” material to fit in the last issue, so I'll continue to follow that seam for a while. (You'll find that downturn and revival is a recurring, uh, theme here at Recurring Thing.)

After returning to design after a year away, I find that Everything Now Looks Very Strange Indeed™. This is another one of my updates on restarting a creative practice (which I’m calling Studio Thing), plus a dose of cultural and design commentary.

(If someone’s forwarded this thing to you in the hope you’ll find it interesting, you can subscribe here to secure my everlasting love. And please, pass it on if you think it might be of interest to anyone.)

🔂🧟♀️ The eternal return of zombie-centred design

Some follow-up on that evergreen topic of what comes after human-centred design: at TEDxSydney I delightedly crossed paths with fellow innovation veteran Carli Leimbach, who’s been thinking about “earth-centred design” as a corrective to anthropocentrism. I’m intrigued. She’s run an initial workshop with some like-minded people, and I’ll keep tabs on her progress.

In other more-than-human news, Anne Galloway recently posted her talk at IndiaHCI 2018, “Designing with, and for, the more-than human”. I’ve been following Anne’s work for a long time, from when the Internet of Things was called pervasive computing, to her more recent work in Aotearoa about sheep. For Anne, more-than-human-centred design means:

“Acknowledging that human beings are not the be-all and end-all.”

“Accepting our vulnerability, acting with humility and valuing our interdependency.”

“Living with the world, not against it.”

Recommended. Also interesting is the “more-than-human design research roll-call” she recently initiated on Twitter. Follow this link if you want to get in touch with people who are active on the topic, at least in academic circles — some familiar names pop up.

🥪🤮 The alternative to curiosity is… hard to swallow

I’ve just wrapped up my NEIS coursework, and to celebrate I want to recount a story about my teacher Jason that also demonstrates why I’m so glad I decided to sign up for this microbusiness training and mentoring program.

A few years ago, Jason was the director of training at a large catering company which had a significant focus on healthcare facilities such as nursing homes. To get a feel for the training needs of his workforce, he decided to tour their workplaces, immersing himself in their day-to-day work. (His CEO was frankly a little surprised by this — as is the case with many sectors, it was uncommon for management to visit the frontlines. In fact, when he urged the Head of Care at one aged care facility to tour the frontlines of her own operation with him, the staff didn't recognise her, and assumed she was a visitor. Yikes.)

While working with kitchen staff in one nursing home, Jason noticed that one resident, a lone old woman, always ordered the same dish: a single salmon sandwich. Intrigued, he asked the staff about this, and they shrugged. “She must like it,” was the reply.

The next day, Jason decided to have lunch with her. After a pleasant meal together, he couldn't contain himself.

“Betty, I've noticed that you always order a salmon sandwich,” he said. (I love that he still remembers her name.) “I don't mean to pry, but, uh, why is that?”

She looked at him for a second.

“It's because I'm afraid,” Betty whispered.

It turned out that Betty had dysphagia — a problem with her pharynx or oesophagus that made swallowing difficult — and was terrified that if she admitted this, she would be placed on the puréed diet of an invalid. Over time, she'd gotten used to salmon sandwiches as the one meal she knew could swallow without issue. And because of her fears, that's all she ate.

“Betty, how long have you been eating salmon sandwiches as your only meal?” Jason asked.

“Two years.” So basically, a resident had been potentially malnourishing herself for years because the systems around providing and talking about choices in this system of care were broken.

After setting her up with a more appropriate (and still chewable) set of diet choices, Jason decided to consult with dysphagia experts and patients like Betty to create a unit of training about these kinds of patient needs, and aimed at preventing such system breakdowns. Everyone at the their client nursing homes could attend. The aged-care nurses who came were flummoxed, telling their Head of Care, “Why are we only hearing about these kinds of problems and solutions from the catering guy? No offence, Jason, but seriously, WTF?”

In the midst of such regimented systems, where industrial efficiency often erases the possibility of supple action or even humane behaviour, I’m grateful that compassionate minds like Jason’s exist. When curiosity seems like it's at death’s door, people like him arrive to revive it.

The reveal: I was initially pretty skeptical about doing the course under Jason because before classes started, I'd gleaned that he’d spent most of his career managing McDonald’s restaurants. It turns out that my fears were misplaced, because I got a lot out of his teaching. While I really don't share his interest in large food systems, either in their experience as a customer nor in their general industrial impact on the world, I'm glad there are people like him enmeshed in such forbidding places, trying to make them more sensitive, responsive and just.

👹👽 First and Last Men

When’s the right time to write a requiem for the human species?

The other night I had the pleasure of experiencing the late Jóhann Jóhannsson’s First and Last Men, a live symphonic and film adaptation of Olaf Stapledon’s seminal 1930 sf novel of future history, narrated by that alien god who lives among us, Tilda Swinton.

(I only knew the Stapledon novel by reputation, and Jóhannsson from his film scores, but was recently prodded to see this production when I watched Philip Kaufmann’s excellent 1978 remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. In a passing exchange that you’d easily miss, two characters chat about their reading habits, and Stapledon’s work is mentioned. More on this later. Intrigued, I pounced on the Jóhannsson version when it arrived in Sydney as part of the Vivid Festival.)

Jóhannsson only uses the last part of Stapledon’s immense story, which starts in the 20th Century and spans the next two billion years. This focus on the last of eighteen successive human species summons a particularly elegiac mood. Responding to the eventual extinction of life on Earth, humans have genetically re-engineered themselves for life on Neptune, and it is these highly advanced Neptunian humans, astonishing in their animalistic diversity, 20-year pregnancies and 2000-year childhoods, for whom Swinton speaks with such characteristically icy dignity. (My god: that voice.)

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

As the camera slowly pans across a series of Yugoslavian Stalinist monuments (you probably know the ones — they recently came into vogue online in the last wave of ruin porn), we cycle through glassy sheets of what anticipatory mourning sounds like: slow arpeggios, and vocals that alternate between the wonderful anonymity of wind instruments and the mewling of cats. (I want to celebrate the two vocalists precisely because they didn’t call attention to themselves: they were exemplary orchestral players.)

The mood is well-earned: despite all the ingenuity and adaptability of these far-future humans, we discover that a cascade of supernovas has triggered our final extinction. Manned interstellar spaceflight — that mainstay of most sf — is revealed as madness, reducing humans at their technological, technological and ethical peak to nihilistic despair. And as the ever-warming climate of Neptune slowly wreaks havoc on their awesome civilisation, the only thing these “Last Men” can do is make telepathic contact with the past — the conceit that enables Tilda Swinton to narrate the tale for us — as they wait for the end.

It’s uncanny how much this story from 1930 resonates with our slowly unfolding climate change disaster. And now that the worst seems inevitable, the intense melancholy of Jóhannsson’s First and Last Men feels fitting — a necessary alternative to either denial or relentless panic. But beyond this, I’m impressed by the supreme ambivalence of Jóhannsson’s take. He makes the Last Men as dignified and magisterial as they are aloof, and their vaunted supremacy is a mixture of authentic maturity and our own sneaking suspicion that in their immortal, genetically-designed perfection, these final humans have lost the capacity to take unexpected action. It’s profoundly sympathetic.

This suggests to me that having a post-human-centred design orientation is very far from being misanthropic. Perhaps we just need to stop pretending that empathy is ever completely possible — who can truly pretend to empathise with a post-human species two billion years in the future, let alone our strange and often unknowable fellow lifeforms, be they vertebrate, invertebrate or botanical? — and instead extend a generalised (and non-paternalistic) sympathy to our neighbours and ourselves. Sympathy is okay. Yes, our situation can be pegged to a combination of pathetic ignorance, shortsighted greed and genuine moustache-twirling villainy. And we are not the centre of the universe. But like others, we are still a species that deserves a dignified mourning.

🦸🏼♂️☄️ Can only a God save us now?

Stapledon’s 1930s future-superhumans continue to haunt me.

When I was teaching art to six-year-olds last year, I did a unit on comics, tracing the emergence of costumed superheroes to the ‘30s.

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

No comment.[/caption]

“Why do you think superheroes appeared then?” I asked the class. “What was going on?”

“IT WAS IN THE MIDDLE OF THE WORLD WARS!” said one student. “MILLIONS OF PEOPLE WERE DYING!” called out another. “My great-grandmother met my great-grandfather in a Spanish flu hospital during World War I!” came another, very-relevant non-sequitur. (It’s easily forgotten that the 1918 influenza outbreak killed at least 50 million people. And yes, these kids are amazing, and publicly funded education is the fucking best.)

Out of the despair of modernity — mechanised mass slaughter and earth shattering pandemics enabled by the globalisation of capitalist industry — we cried out for salvation. Yes, there are many reactionary underpinnings to our superheroic imaginaries (the above image is just the most obvious), but their basis in real trauma behooves us to at least be sympathetic their emergence. We need to take fantasies of supermen seriously (and critically), rather than simply dismissing them as misguided or ridiculous because they’re rather obviously dodgy as fuck. And similarly, we need to take populism seriously.

Make no mistake: while I’m fascinated by downturn and revival narratives, they’re more often than not pretty terrifying: “Make America Great Again” is the clearest contemporary example. And when famed philosopher Martin Heidegger looked forward to “a spiritual renewal of life in its entirety,” he was talking about Adolf Hitler. Don’t look away. Stay and fight in the mud.

🚀🌎 Refuge

Besides talking to the past, the final act of desperation of the Last Men was to transmit proto-organic matter into space, designing it to reassemble on favourable ground in a direction towards intelligent life. (Listening to Tilda Swinton intone gravely about “the Great Dissemination” was just too deliciously weird.) Of course, this is the plot of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, the story that prompted me to explore First and Last Men in the first place: we are being invaded by relentless pod-people, growing out of seeds assembled from “living threads that float on the stellar winds.”

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

Not just taking our jobs — they're stealing Jeff Goldblum's life![/caption]

Too delicious.

Yours in ambivalence,

Ben

0 notes

Text

Lamb of God Returns From Pet Sematary as Zombie Content

This email is powered by the trouble between metalworkers, AI, scratched CDs and the cloud. Doing strategic design, I’m always navigating tensions around narratives of change, often ostensibly involving “technology” or some desired or feared “disruption”. What do such narratives mean? Is change always good? Is there anything interesting in the detritus left behind? I’m always drawn to ambivalence.

So it’s no surprise that in the wake of Easter, my thoughts hover above the border between death and rebirth, collapse and resurgence, obsolescence and renewal. And as Passover season led into May Day, I was reminded that in order to find new life, we sometimes need to do more than just hustle like good neoliberal subjects, and actually mess up the one around us, like the plagues visited upon Egypt, or industrial action.

I keep thinking of that awesome first-season finale of American Gods: wily old Odin tells Ostara, the ancient pagan goddess of Easter, that she’s sustained only by the meagre echo of Spring festivities that survive in our contemporary chocolate egg rituals. It’s time to demonstrate her true power to the New Gods, he says. So in the devastating penultimate scene, Ostara decides to withdraw Spring from the world, leaving the land withered and gnarled.

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

Easter (the ever-delightful Kristin Chenoweth) withdraws her labour.[/caption]

Says Odin:

Tell the believers and the non-believers. Tell them we’ve taken the Spring. They can have it back when they pray for it.

Such chutzpah: it's the Earth, going on fucking strike against the World. So if a Norse god union organiser calls on you next Passover/Easter/May, on which monstrous powers will you draw? How will you Show Them Who You Really Are?

Happy May.

• • •

STATION IDENT: After returning to design after a year away, I find that Everything Now Looks Very Strange Indeed™. This is another one of my updates on restarting a creative practice, with added cultural and design commentary.

(If someone’s forwarded this thing to you in the hope you’ll find it interesting, you can subscribe here to secure my everlasting love. And please, pass it on if you think it might be of interest to anyone.)

🔂🌏 The eternal return of post-human-centred design

Giles Lane from Proboscis took some time to wrestle with my recent ambivalence about human-centred design. Recapping: back in Issue #2 I asked, “Isn’t putting humans at the centre of things what got us into this climate disaster?”, to which Giles replied:

I have a very different understanding of Human Centred Design based on needs rather than desires, including the need to co-exist within a healthy environment/ecosystem. It draws on its 1970s roots, based in radical response to exploitation of people & communities by privileged elites.

Those of us whose work has always embraced a dialogue about ethics, values and been infused by a genuine concern for human centred, participatory design will always be on the periphery of the mainstream.

The thing is, Giles and I don’t have a very different understanding of human-centred design — I completely understand where he’s coming from. When onboarding new designers at Digital Eskimo, I was always at pains to emphasise how the heritage we were inspired by — the Scandinavian participatory design tradition, amongst others — was a truly radical seam of practice that had been papered over by the rather less exciting idea that “listening to customers is common sense for business.” 🤮

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

"From Fra Burmeister og Wain's Iron Foundry" by Peder Severin Krøyer, 1885.[/caption]

I would argue that contemporary design methods, whether they acknowledge it or not, owe a massive debt to organisations like the Norwegian Union of Iron and Metalworkers, who in the 1970s were disruptively intervening in debates about automation and computerisation. Rather than simply being “for” or “against” the machines that were threatening to replace them, workers became high-level designers of workplace technology systems. Now that debates about automation have again recurred in this age of AI, we would do well to pay attention to these traditions.

But I’d still argue that in spite of the traditions Giles and I both still cherish, the balloon of “human-centredness” has nonetheless semantically burst, and was never completely tenable in the first place. An analogy: “Third World nationalism” presided over some heroic moments in the struggle against colonial domination, but I nonetheless think that nationalism was never exactly a good thing in the first place, and also tends to yield ever-decreasing returns as a corrective to very real global inequalities.

I think we simply need new beacons for navigating our more-than-human design landscape. These landmarks might include the work of people like Anab Jain from Superflux (see this talk at the IxDA’s Interactions 18 for a good overview of her work), Anne Galloway from the More-Than-Human Lab and others. Let’s all watch that space, and please let me know if you find anything interesting — I’ll feature it here in a future issue.

🐕🤖 Old dogs, new

I was at the City of Sydney’s latest CityTalk, “Our Future With AI and Its Rise In China”: a keynote from Robert Hsiung, chief of the online tech education platform Udacity in China. I found the evening singularly unimpressive. Rather than indulge in wide-eyed liberal panic about Chinese authoritarianism by mining a seam of yellow peril rhetoric, the subsequent conversation went in the other direction entirely, studiously avoiding any discussion about machine learning’s use by the Chinese surveillance state.

Hsiung emphasised the importance of “mastering the machine” to staying relevant as humans in an AI world, citing case studies in which “even” blue collar Chinese workers with a mere secondary education were successfully retrained by Udacity as AI programmers. Sure, they want to democratise tech skills, and I agree that adaption is preferable to sticking one’s head in the sand, but when Hsiung characterises people on society’s periphery as “people who didn’t study enough in school” (actual words used), I’m not seeing Norwegian metalworkers taking power into their own hands. I can’t help but wonder there’s an implicit element of patronising, tut-tutting disciplinary action in this imperative to retrain before the Singularity overwhelms the uninitiated.

Hsiung’s keynote ultimately devolved into a stiff, extended advertisement for Udacity, reminding me of nothing so much as a dystopian propaganda spot for a corporation like Omni Consumer Products in Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop. If this deeply uninteresting event is the best the city’s public sphere can do on the AI front, Lord Mayor Clover Moore ought to be embarrassed.

💿☠️ Obsoletely nothing

I’m alive / I’m dead

— The Cure, “Killing an Arab”

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

Image by Rishi Deep at Unsplash[/caption]

When I realised not long ago that some of my primary school art students were habitually getting stuck in their creative endeavours, I got them to look for stimulus in unlikely places. “Look at what’s been thrown away at your feet,” I told the class. The next day, my own advice returned to me as a gift.

Local government rubbish cleanups are the rhythmic heavings of the suburbs. A few times a year, we find the unwanted and the outmoded disgorged onto the street (and more often than not, you can find me rummaging through the junk). As I got off the bus that afternoon, an object on the pavement suddenly came into focus as having joined the the ranks of the obsolete: a CD tower. A tall, narrow shelf, made solely to hold a large collection of compact discs.

A few years before, it had been cathode ray tube TVs and VHS tapes on the nature strip. Today, a piece of furniture had lost its one purpose. Next to it, victims of the streaming moment, were endless shiny platters: redundant CDs and DVDs. I felt a pang of melancholy at this diorama of churn, but couldn't muster up any actual nostalgia for CDs. I suspect that I’m not alone in this.

In 1998 I wrote a short science fiction story that touched on the possibility of being nostalgic for media formats that were then only just beginning to be challenged by new forms of media like the Internet. Mirroring what I was then seeing with the fetishisation of vinyl records, my 21st Century protagonist, Sebastian Tan, was a CD fetishist. While I gave Seb the ability to hack into streaming media services to get lasting access to the discrete music files themselves, this streaming pirate still preferred physical media.

And the act of opening the digipak and sliding the antique CD in place was a ritual. Trainspotting. When he first found Silver Rocket, it was a revelation. It was a place. He’d just stood there, soaking it in – the lost garage punk compilations, the late ’90s Skint family, the Anokha artists. All the music physically in the same room. Old silver platters and everything.

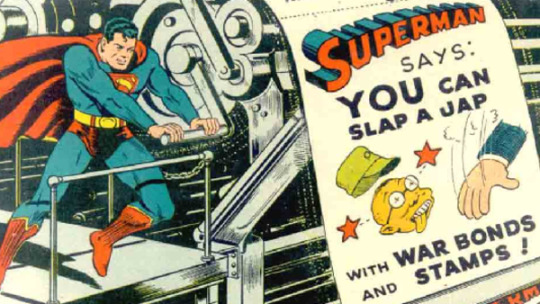

Since this was 20 years ago, I don’t remember how much I actually believed how likely “CD fetishism” would actually be in the 21st Century, but the idea certainly seems ridiculous to me now. Naked optical discs like the CD and the DVD seem to be missing the qualities that would guarantee their fetishisation. There’s something fragile, bare and unromantic about them. It strikes me that this is perfectly illustrated by two Kanye West album covers:

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

On the left is his 2013 masterpiece Yeezus, which unfortunately affects the style of a blank CD. To the right is its recent sequel, the not-so-great Yahndi, which makes up for its mediocrity by aping a magnificent Sony MiniDisc, a fabulous storage format that was largely outmoded by the turn of the millennium.

Don’t be fooled by the similarities, because these two things are chalk and cheese. MiniDiscs were cool. CDs are not. In addition to enclosing a rewritable magneto-optical disc inside a permanent case, giving them a more tactile quality, MiniDiscs were also smaller in the hand. And in the cinema of the mid- to late-’90s, they were a shorthand for “vaguely futuristic storage media”.

MiniDiscs played a significant role as storage for VR contraband in Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days (1995). Ralph Fiennes furtively stashes old VR recordings of happier times with Juliette Lewis in a shoebox of MiniDiscs, but one particular disc that comes into his possession becomes the MacGuffin in the film’s thriller plot.

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption] [caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

Gotcha: VR proof of racist police brutality… captured on disc! (See how actually compact it is in the hand?) And in the Wachowski’s The Matrix (1999), MiniDiscs return as contraband, this time stashed heavy-handedly inside Neo’s copy of Jean Baudrillard’s Simulation and Simulacra. By this time they’d become almost retro-futuristic, somehow at home with the acoustic coupler modems and Bakelite handsets.

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption] [caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

There’s something reassuringly tangible about the MiniDiscs in these movies. Their secret hiding places are enticing. And the sight of these contraband objects being exchanged for physical cash is just too delicious.

In short, I wish I could be nostalgic for CDs like I am for MiniDiscs (which, truth be told, I never used that much). It’s as if MiniDiscs occupy in my imagination a subjunctive road-not-taken that would have made disposable optical media less crass. I almost feel like mad old King Denethor in Lord of the Rings, wishing that it was his less favourite son who died in battle.

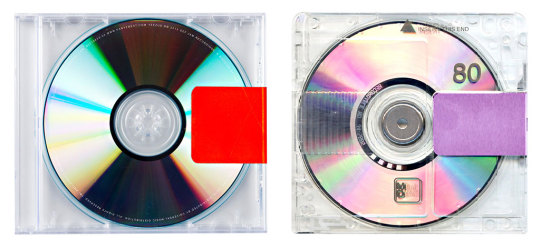

🧟♀️💾 Zombie content

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

There are folders on my laptop that owe their structure purely to having originated on random old floppy disks that I found in the cupboard. Some of these files are unreadable, despite being Microsoft Word documents. Microsoft are amongst the most slavish followers of backwards-compatibility in the technology industry, even to the extent that they replicate the behaviour of ancient bugs in newer versions of Windows in order for apps to run smoother, but it seems that documents created in versions that predate Word 98 are lost to me. (I’ve learned my lesson: these days, everything’s in plain text Markdown.)

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

I’m intrigued by the file titled “WHOREBOY.doc”. From what I recall, it contained notes for a graphic novel I was planning about an undead sex-worker-of-colour in the antebellum South. A black 19th Century superhero, Whoreboy kicked arse. At least, that’s what I remember.

Update: turns out that plain text editors can glean most of the content from old binary Word files. My memory proved largely correct. Whoreboy was a runaway slave rent-boy who could sprout tentacles from his back and rise from the dead. In moments of crisis, the old slaver’s brand on his shoulder would glow, perversely triggering latent superpowers. (I’d flagged the branding of African American slaves for further research. These days I’d be in Wikipedia rabbit-hole instead.)

A snippet:

Whoreboy’s mentor, an old “witchdoctor”, mentions Jimbo in the Mirror, the terrifying folk spirit that you can only see at midnight.

“Really?” asks Whoreboy.

“No, I made it up,” he says. “Them white folk love that shit. Brown Eye for the White Guy, I call it.”

Okay, perhaps it needs more work. But think of the possibilities!

What’s the funniest skeleton in your digital closet?

🎼🔁 Refrain, with key change

It’s apparent that I often think inordinately about the past while navigating change, even if it involves a kind of “meta-nostalgia” (as above: when nostalgia doesn't seem possible, I feel “nostalgic” about “feeling nostalgic”). As I’ve said earlier,

I often look to the past when I think about the very idea of the future, not just so we can avoid repeating “the mistakes of history” (as important as that might be), but because as designers trying to make the world a better place, we really should honour the creative friction that happens when the weird fragments of the past we continue to live with rub against the potentials of the present moment. (For a future-oriented person, I do an amusing amount of hoarding! In my view, forgetting to deal with legacy systems, even if “dealing with them” involves actively destroying them, is tantamount to vapourware dreaming.)

But I’m also realising that to hover in the futurepast in the way I do means more than just coming to grips with the past, with all its traumas and potentials. I suspect that my own retrofuturistic tendencies are an instinctive way to express the bind we find ourselves in as makers of newness (designers, strategists, “change-makers”) under late capitalism: so much of our work these days seems to involve making organisations more adaptable, resilient, nimble and innovative, but how this might also be a friendly form of neoliberal shock therapy? How much is the agility of the contemporary design-led organisation a way to produce subjects who compliantly flex with the ever-shifting sands of the market?

I love to tell people about my work facilitating cultures of design possibility in organisations. After a productive co-design session, a client team-member will express joy about the concepts they’re helping to flesh out.

“You realise, don’t you,” I say, “that you’ve nominated yourself as a key part of the leadership for this project, right?”

The resulting look of terror on their face — the one that says, “B-BUT THAT’S NOT IN MY 12-MONTH WORK PLAN!” — is one that I always relished. And so I drag them kicking and screaming into the future. While I’m not about to defend calcified organisational cultures of bureaucratic planning, I’m now a bit more equivocal; I can see some continuity between my own gleefulness and the forces that are casualising workforces around the planet.

Perhaps my hovering, with my face turned to the past as I explore futurity (and like Lot’s wife as she looks back at Sodom even as she flees), is an admission that security and belonging are worth something in these times. So as we experience the churn of obsolescence and innovation, let’s keep our wits, sympathies and sense of revolt about us.

A sustainable portion of all my love,

Ben

0 notes

Text

A time-travelling, galaxy-defending archaeologist – Recurring Thing #4

The scent of the future is wafting in. I’ve been breathing it in, choking on it, attempting assimilation.

Over the last few weeks, I’ve enrolled in a business startup program, went to a workshop about speculative design, and thought about where I’ll be in 10 years. But after seeing The LEGO Movie 2, I hope it’s not being a raptor-training archaeologist from space. (I guess you had to be there.)

After taking an extended break from social design work “to get some perspective” (ahem), I find that Everything Now Looks Very Strange Indeed™. This is another one of my updates on restarting a creative practice, with added cultural and design commentary.

(If someone’s forwarded this thing to you in the hope you’ll find it interesting, you can subscribe here to secure my everlasting love. And please, pass it on if you think it might be of interest to anyone.)

“Where do you see yourself in 10 years?”

In Issue #2 I mentioned that I’m starting a small strategic design practice called Studio Thing. To help this along, I recently applied for the Australian Government’s New Enterprise Incentive Scheme and am now enjoying free business training for several months, and ongoing business mentoring for a year. I’m usually sceptical of such government programs, but happy to report that our trainer Jason is hilarious, and that my cohort is vibrant and diverse. It includes one of Australia’s leading forensic investigators, an aerospace startup that's designing hyper-spectral imaging satellites in a suburban Sydney home, and three mental health-related startups.

As you’d expect, the assessable part of the training feels a bit superfluous. The value is instead in the solidarity, support and collective wisdom you get in the room. In this context, formerly snooze-worthy operational details about business become far more alive. Frank feedback still rules, but deviates from the tech-bro/shark-tank consensus; for example, after an exuberant elevator pitch last week by one of the mental health startup founders, the most devastating feedback came from one of the quietest voices in the room, a softly spoken Korean couture designer who lacks confidence in her English:

“You felt like a wall,” she said. “If you want me to come to you for help, I need to see you bend.”

Uncommon wisdom.

No/future

Being in microbusiness school involves a lot of talk about strategy, and one of the contradictions of thinking strategically is that just as we need foresight in order to endure, we must also embrace uncertainty to thrive. We need a supple sensibility to survive our times. In this, I’m sympathetic to both the apocalyptic nowness of the punk phrase “no future” (which is much more than nihilistic rage) and the science-fictional tendency to imagine the future.

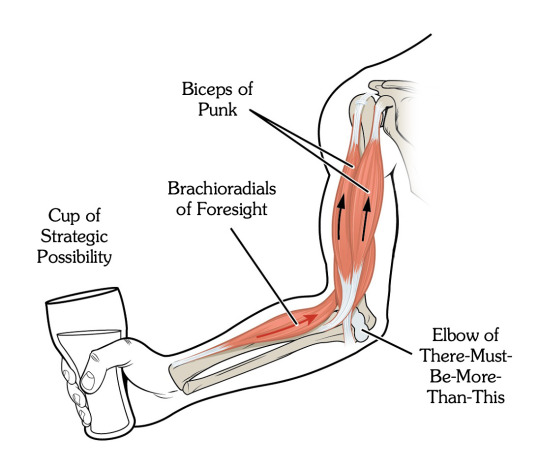

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

“No future” is one of the most important messages in punk. In a way, contemplating that “there is no future” opens up a new politics, a much more prefigurative politics. It’s no longer a question of waiting and dreaming of utopias, but of doing what we need to do here and now, and in the ways we can and want to. We’re not waiting for further instructions or permissions to get started. We will take ownership of music and spaces. In punk, anyone can pick up a guitar while someone else starts singing, speaking, doing.

— Guiomar Rovira, “No Future: From Punk to Zapatismo and Connected Multitudes”

Urgent and dangerous, disavowing the future forces a sense of possibility to arrive in the vacant spaces of the present. A very different strategy from, say, Star Trek’s optimistic and intricate future history of the 23rd and 24th Centuries.

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

How I ridiculously imagine punk and speculative futures working together[/caption]

But despite being an art of extrapolation, science fiction has often been a metaphor for the concerns of the present, or an opening of possibility, rather than simply a literal attempt to predict the future. And its speculations are often untamed and unruly. “Future” and “no future” are thus closer than we might initially suspect. With both turning on the same hinge (of “there must be something more than this”), I’d like to think that together they can contribute a kind of lubricated friction… towards greatness.

Visions

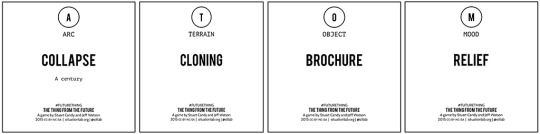

As it happens, the first edition of Visions, a handsome new science fiction magazine, just landed on my desk as I finished typing the previous sentence. It came with a sexy postcard:

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

Uncanny! Visions is “a science fiction magazine where writers, designers and researchers of the past and present come together to explore the future.”

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

To be totally honest, I really ordered it to experience Marvin Visions, the awesome retrofuturistic typeface that editor Mathieu Triay cut specially for the magazine, but the whole package is obviously compelling and relevant to my Recurring Thing concerns. Back in the early ‘80s, the magnificent Omni magazine mixed fiction and non-fiction about science and technology in a way whose promise has yet to be truly fulfilled, and Visions is a good step in that direction. More later.

Dying stars and fossil fuel archaeology

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

When I recently taught a second grade school art class with a theme of “the future”, I primed them with a range of stimuli: a familiar adage, “The best way to predict the future is to invent it” (attributed to everyone from Alan Kay to Abraham Lincoln); a peek at Future Cities, the book my father gave me when I was six years old and which directly inspired the work I now do; plus, many examples of how science fiction has directly inspired contemporary technologies.

I then invited each student to visit the future, travelling to a date of their own choosing. We set our future destinations using the control panel from Back to the Future’s DeLorean, and to the wheezing sound of the TARDIS time rotor (yes), we entered the time vortex.

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

Our challenge: to draw what we saw on our arrival. A group of 7-year-old girls who were usually into drawing unicorns and rainbows surprised me by collaborating on an awe-inspiring scenario, set millions of years in our future: the sun becomes a red giant, swallows the Earth and ends human civilisation. But in a hopeful coda, the solar system’s habitable zone shifts to the orbit of Pluto. (Yes, they went into this much detail.)

Some kids imagined a range of consumerist wish-fulfilment utopias, full of crazy gadgets, but an interesting thing happened: debate spontaneously broke out about how desirable some of these really were. Calvin, the shortest kid in the class, sat grumpily at the back of the class and delivered a running commentary on the ecological impact of each scenario. “Where’s the energy coming from? Fossil fuels,” he’d snipe. “More fossil fuels.” And… “FOSSIL FUELS!!! WHAT ARE YOU THINKING???” It led to some interesting discussion. (Later that week, I overheard a child from this class ask, “Mummy, what are ‘fossil fuels’?” Which. Is. The. Best.)

There was a future in which everybody lived forever. “What do you think would happen if this came true?” I asked the class. “That’s scary,” my daughter’s friend Reyna replied, “because if everyone lived forever, it would reduce the capacity of the Earth to nothing.” (Her exact words.) The mind. It boggles.

“Fossil-Fuel” Calvin’s future scenario was a barren, charred wasteland.

Design as a race to dystopia

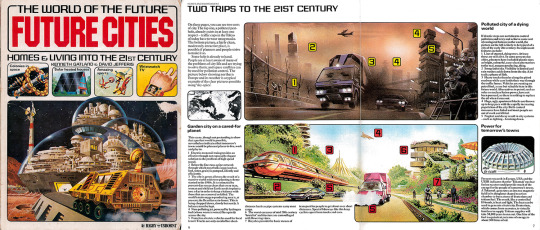

During the Sydney Design Festival, I had the fortune to attend a Speculative Design workshop run by the indefatigable Tina Fung of Meld Studios. Besides using the same Alan Kay/Abe Lincoln quote (snap!), Tina introduced us to Situation Lab’s game, The Thing From the Future, in which players visualise objects inspired by random cards that suggest its different aspects: its future timeframe (“Arc”), area of society (“Terrain”), general form (“Object”) and emotional charge (“Mood”).

Our group drew these cards:

[caption align="alignnone" width="980"]

[/caption]

The concepts people build around such provocations are usually passing exercises in extrapolation, but to teach us critical foresight, Tina got us to take our ideas a little more seriously, running them through a matrix of potential economic, technological, social and ecological consequences. Things got unnerving.

After my experience with the time-travelling children, I wasn’t surprised that most of us created dystopian scenarios. One group created a food-based social credit system within the last outpost of human civilisation — a space station in orbit above a dead world. While those displaying “optimal” behaviour could eat well, those relegated to the bottom of the system could only eat “Hungry Bread”, which left you feeling more hungry. The perversity generated much, uh, food for discussion.

To relieve human pressure on a future Earth, my team created an authoritarian eugenics program for interstellar colonisation. Those deemed genetically fittest for colonial adventures would be endlessly cloned to form the future interstellar population. Like the Hungry Bread, it was obviously perverse, but more disturbing was that one outspoken designer on our team actually relished the hyper-instrumentalism of this scenario. In the name of human survival, extreme measures could somehow be justified.

Beyond the obvious point that eugenics runs counter to a just society, I suggested that it also disregarded the distinct possibility that societies require diversity and its attendant challenges of cosmopolitanism in order to actually function. Without an ethic of inclusion, a society of Alphas might easily self-destruct in an orgy of atomised cocksureness. He snorted in reply.

“Inclusive design is bullshit,” he bellowed, “because design is exclusive, by its very definition! Tailoring our products to exactly fit the needs of an ideal customer is design excellence.” In his vehemence, his face began to flush. “Allowing rubbish common denominators to dilute excellence isn’t just bad design, it isn’t design.”

I’ll consider the possibility that this guy was trying to get a rise out of me, but remember when I recently expressed my misgivings about how contemporary design’s largely uncritical enthusiasm for highly tailored experiences might align too neatly with the way capitalism feeds social divisions? This guy was a living embodiment of everything I see going wrong with my profession. And yet he was factually correct, in a manner of speaking: in its ultimate distillation, design seeks to optimally shape the world to specific ends, and taken to its logical conclusion, we might end up with our nightmarish Things From the Future.

By throwing spanners into its heart, I want to dedicate my efforts to prevent this future design apocalypse.

This edition was brought to you by Go Home Productions’ classic Sex Pistols/Madonna, mashup, “Ray of Gob”. Watch and listen here.

A sustainable portion of all my love,

Ben

0 notes

Text

A Machine For Hammering the Soul, With Robotic Padres

It's a juicy weekend read for you, in defence of piety (!)…

📖📖📖

After taking an extended break from social design work “to get some perspective” (ahem), I find that Everything Now Looks Very Strange Indeed™. This is another one of my updates on restarting a creative practice, with added cultural and design commentary.

(If someone’s forwarded this thing to you in the hope you’ll find it interesting, you can subscribe here to secure my everlasting love.)

Today I want to write of vibrations of the soul, the experience of the divine and the habit of prayer. With robots. Yes.

I remain a staunch unbeliever, and yet I find that these apparently religious terms become more useful when I’m wrestling with certain practices: of creativity, of recovery, of becoming a better participant in my communities (local or cosmic). Each of these requires me to paradoxically affirm my own sense of agency by simultaneously curbing it.

For example, working on our addictions is never simply a matter of exerting our individual willpower (which is called “white-knuckling it” in recovery culture, and clearly unsustainable); we instead need to make the choice to surrender to the collective agency of community.

And the other week, my dear friend Janelle and I attended a writer’s meetup that involved everyone sitting down and just doing some fucking writing. As we sat in a zero-ambience pub bistro, beavering away, she passed me a note:

“THIS FEELS FORCED AND NOT RAD.”

Agreed, the venue was very much not rad, and we weren't a very inspiring sight, but to be fair to the rest of us, Janelle’s own writing is driven by uncommonly strong affective tides that would wreck a less glorious being. I’d argue that for most people, sustainable creativity needs in some way to be “forced”, and this isn’t a bad thing. My own creative endeavours need to be sustained by the scheduled habit of accessing an animating spirit that might reveal itself to the solidarity of a congregation. (It does need a better venue, though. Blech.)

Such appeals to the beyond have given me a new, practical appreciation of the rigours of piety. But lest I be accused by Slavoj Žižek of some lacklustre, postmodern, liberal-secular appropriation of spirituality, I need to leaven this stuff with a good dose of machines and robots to keep it interesting to me. 😉

Eternal return: burials, and when the earth rejects us

First, some follow-up.

Did you know that in this wonderful medium of email newslettering, you can simply reply to any of these missives from me, and that your reply will appear directly in my everyday, personal email inbox? It’s real email. No really, I love this, so replies are encouraged. Meanwhile, I’m really heartened by the generous messages I’ve received from you thus far. Also, I don’t know some of you, and this mixture of the known and unknown is tantalising.

Answering my call in the last issue for objects that deserve “burial rites/rights" with us, Andrew (who I know can light a fire with his bare hands) replies that “I would bring with me a wooden spoon for my cooking, a headlamp for reading late at night and camping, and a vr headset because I know I won’t be affording one in this lifetime”. That would just be a simulated, still life VR headset then, right?