Text

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

It’s been quite a week.

On Monday, Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) began an epic speech in the Senate calling out the crisis in which the nation finds itself. He finished just over 25 hours later, on Tuesday, setting a new record for the longest Senate speech. In it, he urged Americans to speak up for our democracy and to “be bolder in America with a vision that inspires with hope.”

Shortly after Booker yielded the floor on Tuesday night, election officials in Wisconsin announced the results of an election for a seat on the state supreme court. The candidate endorsed by President Donald Trump and backed by more than $20 million from billionaire Elon Musk lost the race to his opponent, circuit court judge Susan Crawford, by more than ten points.

On Wednesday, April 2, a day that he called “Liberation Day,” President Trump announced unexpectedly high tariffs on goods produced by countries around the world. On Thursday the stock market plummeted. Friday, the plummet continued while Trump was enjoying a long weekend at one of his private golf resorts.

And then today, across the country, millions of people turned out for “Hands Off” protests to demonstrate opposition to the Trump administration, Musk and the “Department of Government Efficiency” that has been slashing government agencies and employees, and, more generally, attacks on our democracy.

In San Francisco, where Buddy and I joined a protest, what jumped out to me was how many of the signs in the crowd called for the protection of the U.S. Constitution, our institutions, and the government agencies that keep us safe.

Scholars often note that the American Revolution of 250 years ago was a movement not to change the status quo but to protect it. The colonists who became revolutionaries sought to make sure that patterns of self-government established over generations could not be overturned by officials seeking to seize power.

We seem to be at it again….

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I thought scientists were going to find out exactly how everything worked, and then make it work better. I fully expected that by the time I was twenty-one, some scientist, maybe my brother, would have taken a color photograph of God Almighty—and sold it to Popular Mechanics magazine. Scientific truth was going to make us so happy and comfortable. What actually happened when I was twenty-one was that we dropped scientific truth on Hiroshima.” ― Kurt Vonnegut

338 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince Harry tells ITV News correspondent, Rebecca Barry why he will never bring his wife Meghan back to the UK. Harry made an appearance in the ITV documentary about illegal phone hacking and the British tabloids called, “Tabloids On Trial”. It had aired on ITV1 & ITVX at 9pm on (7/25/24). As we all know, Harry has a on going lawsuit against a British tabloid.

It has been recently announced that the next Invictus Games 2027 will be hosted by Birmingham, UK. It will be the 8th Invictus Games. Birmingham competed against six cities around the world for the bid. Birmingham won the bid through its strong commitment to the welfare and recovery of serving personnel and veterans.

I think it’s safe to say Meghan won’t be there for this one.

Congratulations to Birmingham, UK. 🙃

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The tipping point. :: April 7, 2023

Robert B. Hubbell

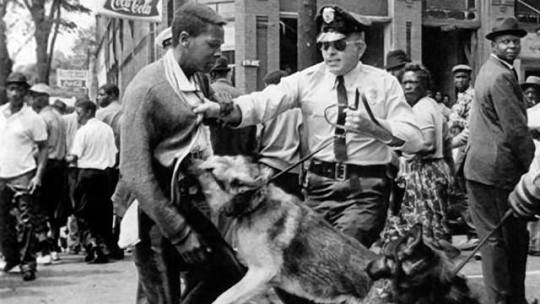

I cannot leave the events of today without comment. In three respects, America reached a tipping point on Thursday. It may take months or years for us to appreciate that fact, but historians will mark April 6, 2023, as the high water mark of the retrograde, anti-democracy movement of MAGA extremism.

In particular, the naked racism of Tennessee Republicans in expelling two Black legislators but not a white legislator for identical conduct in protesting gun deaths of schoolchildren has removed any ambiguity about the racial animus of MAGA extremism. One commentator described the events in the Tennessee legislature as the birth of “the New Civil Rights Movement.” Because that second birth occurred under the scourge of gun violence directed at children, the merger of those movements will be unstoppable. We witnessed two powerful voices emerge in Tennessee on Thursday. They will become national leaders in a movement that will attract new constituencies to the civil rights, anti-gun movement.

The second tipping point was the publication of the Pro Publica report that exposed the grotesque corruption of Justice Clarence Thomas. Thomas accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars (possibly millions) in the form of free travel from a Republican megadonor and failed to report those gifts as required. In truth, the corruption of Justice Thomas has been replicated by other members of the conservative majority on the US Supreme Court. We need only scratch the surface to find that corruption. There is no turning back. And make no mistake, John Roberts has presided over the open wound of corruption during his entire tenure. He must be held accountable for his dereliction of duty, as well.

Finally, Idaho has criminalized the constitutionally protected right to travel across interstate lines. MAGA extremists have converted the Dobbs ruling that there is no right of privacy in the Constitution into a perverse mandate to deny Americans other rights that are plainly protected by the Constitution. They are doing so under the guise of regulating reproductive liberty. That strategy will lead to the demise of the GOP. Indeed, we have seen the seeds of their destruction in Kansas, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

[Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter]

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Katz in New York

Margaret Katz, a vivacious and wildly productive student – somewhere between Den Mother and Leader of the Pack -- also modeled for drawing classes. Her father, Martin Katz, was a New Yorker with, in his own words, “a rich fantasy life” wherein he was the founding director of the American Institute of Business Espionage (a purely ceremonial organization the actual mission of which seemed to be to hold an annual convention on the founding date, October 25, which, by another odd coincidence, was also the date of my annual Fall “mixer” in Athens). I actually attended the A.I.B.E. convention in 1978, and I still carry Marty’s “business” card in my wallet.

Somewhere around 1977 or so, following a trip to New York (with The Fans?), Margaret made a spectacular drawing that imaged the rapid succession of flashing lights, swiftly disappearing architectural elements, graffiti, and whatever else she might have seen in a New York subway tunnel from a train in motion. As I recall, she made it on several rolls of butcher’s paper, on which she could work only a few feet at a time, unaware, for any practical purpose, of what had gone before, and what was to come after, the section she was working on. Unrolled (or perhaps only partially unrolled), it covered the entire hallway gallery in the Art Department, and was perfectly coherent. Of the thousands of student drawings I saw in ten years at UGA, it is the most memorable. In the thousands of times I rode the subway over 25 years in New York, I never failed to see it through Margaret’s eyes, and, perhaps for that reason, a subway ride never became routine.

The art heightened the experience, and the experience validated the art: when that happens, truth becomes beauty, and beauty reveals truth, and that, by God, is all I need to know, and all you need to know, too. Johnny Keats got it right, and so did Katz.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ir takes time to get over losing a faithful friend. I read somewhere that the brain does not distinguish between mourning the death of a person, a pet, or a literary character. Best wishes to you, Marlowe and Ann. It takes time to process grief. Take as long as you need and do it in your own way. We will be here for you.

She’s still adjusting to being allowed to sleep on the until-recently-forbidden bed. #MarloweMonday https://www.instagram.com/p/CJXj-zSDolS/?igshid=1rmupzikkfp30

589 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dancing On The Tables: A Celebration Of The Athens-Atlanta Music Scene, Starring The B-52’s, The Fans, The Brains, Glenn Phillips and some act named R.E.M.!

I probably wouldn’t have agreed to write this article, except that Vanessa and Richard pitched an appealing idea: contact people from the Atlanta and Athens music scenes of the 1970’s-80’s and ask them three questions. Whatever you get from them goes in the article. No herding-of-cats was to be involved. No follow-up reminders, and no begging and pleading allowed.

After spending the past five years of my life working on projects that involved boatloads of goading and prodding, how could I resist participating in this experiment? I sent out a copious amount of emails and got back five responses. The thing is, my five correspondents perfectly exemplify the Atlanta/Athens music connection. Keith Bennett was one of the UGA art students who lived in the vortex of the Athens creative scene, a crumbling ante-bellum mansion belonging to UGA Professor Jim Herbert. Darryl Rhoades was the flamboyant and ferociously funny frontman for Darryl Rhoades and the Hahavishnu Orchestra, and Kevin Dunn was the guitarist for Atlanta band The Fans. Doreen Cochran was band coordinator for The Brains, and Glenn Phillips was guitarist in The Hampton Grease Band. From their stories and experiences, you will be able to see how the paths of the two cities intertwined.

I was a product of the interweaving of Athens and Atlanta, having grown up in both towns and participated in the music scenes in both places. Let’s start with me, and move on from there to Keith Bennett and beyond.

Maureen McLaughlin

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both):

Both. Definitely both.

2. Your connection to the music scene:

I was the B-52’s first manager. I also did a lot of networking between bands in Athens and Atlanta and other places as well, getting the Fans their first gig in NYC, shortly followed by doing the same for the B’s. Before that, I was going to concerts at the Twelfth Gate in Atlanta and in Piedmont Park.

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

I grew up in Atlanta and went to high school in the Sixties. As soon as I got my driver’s license, my mother turned the family car over to me. The deal was that I had to chauffeur my sisters and brother during the day, and at night I could do whatever I wanted. Having that freedom enabled me to start hanging out at the Twelfth Gate coffeehouse in Atlanta, an experience which changed my life. The Twelfth Gate was started by Grace Methodist Church to minister to the unchurched street kids hanging out on the Strip. It became a mecca for jazz and blues musicians who liked to play there because the audiences were fantastic, and it was one of the only truly integrated places in Atlanta where they could play. The club was in an old house, and the stage was in a corner of the dining room. The audience crammed into every nook and cranny of the first floor, jamming into the living room and kitchen, and spilling out on to the front porch. The house band was (or might as well have been) The Hampton Grease Band, a brilliant group of musicians who made the panes rattle in the windows with their wild style of jazz. I also saw McCoy Tyner there, and Larry Coryell, Pat Metheney, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGee, Big Mama Thornton, John McLaughlin and many other incredible musicians, including my favorite, Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Between sets, the musicians hung out with the audience, and since many of the players were on a circuit where they came through town regularly, it was not hard for the audience to become friends with the musicians.

I also spent many afternoons in Piedmont Park listening to music. Many groups would play shows for money on Friday and Saturday nights, and then show up at Piedmont Park to spend Sunday afternoons making music. An incredible assortment of people came through there. The Allman Brothers were at Piedmont so, so many times that their music saturated my soul. It would not be unusual to find Edgar and Johnny Winter, Spirit, or the Grateful Dead playing there. Something was always going on, and it was all pretty wonderful.

When I moved to Athens to go to UGA, I got on the Concert Committee for the Student Government, which was an excellent way to get Atlanta bands to Athens. I also helped to start a coffeehouse in Memorial Hall at UGA, but it got shut down because we were dancing on the tables and playing inappropriate music, according to someone in the administration. All during my college years and afterwards, I ran a rut in the road from Athens to Atlanta, going to shows at Rose’s Cantina, 688, the Great Southeast Music Hall, and a number of other Atlanta venues.

4. What are you doing in music now?

I have been a part of the stage crew for our local music festival, AthFest, for the past 14 years. I get local people to announce the bands on the two outdoor stages. I am also slowly doing the research to write a book about Pylon.

5. Tell us one story you have never told anyone before about your time in a band or working in the scene.

After the Twelfth Gate closed, many of the musicians who played there began playing at the Great Southeast Music Hall. The two venues could not have been more different. While the Twelfth Gate had a bunch of random second-hand chairs along with sofas and armchairs crammed into a tiny space, the Music Hall was a proper theater with a large stage and plenty of room for several hundred people.

The first time Rahsaan Roland Kirk played at the larger venue, I went to see him, and the crowd was horrible. Instead of listening to the music, the audience spent the whole night trying to talk over it. At the end of the evening Rahsaan Roland Kirk told the audience that they were the worst group he had ever played in front of and that he would never come to Atlanta again. “If you ever want to see me again, you will have to come to the Village Vanguard in New York,” were his parting words to the spectators, who by this time had enough sense to shut up.

I went up to him afterwards to apologize for the crowd’s behavior and he told me, “Little girl (he always called me that), you better get out of Atlanta.” I told him, “Yes sir, I will.” Two weeks later I moved back to Athens, beginning one of the most intense periods of my life. The B-52’s had flown the coop, but Pylon was on the rise, as were R.E.M., Love Tractor, The Side Effects, and a whole host of other bands. We had some experiences during that time that can only be told one-on-one, and only then to the most discreet of friends.

Photo: L to R: Cindy, Maureen, The Incomparable Phyllis, Fred, Kate, Keith, Ricky. Photo taken before an afternoon show in Piedmont Park, date and photographer unknown. Courtesy of Maureen McLaughlin.

Keith Bennett

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both):

I was involved in the music scene in both Athens and Atlanta

2. Your connection to the music scene:

The B-52’s, The Fans, Pylon, The Tone Tones, REM. I was mostly a fan of the bands but I did create graphics for the B-52’s including posters for the group’s performances at the GA Theater in Athens and CBGBs and Max’s Kansas City in New York City. I also designed (with Keith and Ricky’s guidance) their independent single on DB Records, Rock Lobster/52 Girls.

In the execution of these projects I designed a logo for the B-52‘s as well. The aforementioned show posters and logo were also part of my exit exam to graduate from UGA with a Graphic Design degree but the work was undervalued by my professors. I received an F for the project and wasn’t allowed to graduate. (I returned the following fall quarter and created an illustration montage in pencil which is what they wanted, not of the B’s but of the Beatles and was able to graduate from college and start work immediately washing dishes at Friends restaurant in the Georgian Hotel, Athens.)

1978 B-52’s poster designed by Keith Bennett. The photo is of Bennett as a child. Bennett designed the now-iconic B’s logo. Courtesy: Chris Rasmussen, Art Rocks Athens.

I also accompanied the group on some trips to NYC and helped out here and there. Later, when they signed with Warner Brothers, I became their first roadie along with Moe Slotin, who actually had much experience in Rock and Roll touring. Since I basically lied to secure the gig, Moe ended up having to train me and he did an excellent job. It was the modern-day equivalent of running off to join the circus, an apt metaphor in more ways than one. Although ultimately it was not my life’s calling, I did end up working three US tours, one Australian tour, and two European tours. I also worked for the B’s in Japan.

At first I did the back line, the keyboards, and set out Fred’s toys and Cindy’s bongos along with being responsible for restringing and tuning every one of Ricky Wilson’s guitars, every show night which was about 5 to 6 nights a week, for 8 weeks during that first tour. Ricky was a unique guitarist to say the least and played guitars strung with 4 and 5 strings instead of the standard 6 and he had a different tuning for each guitar. On some I had to change the tunings during the show as he finished with a guitar that he would be using later in the set, which needed another tuning. I was responsible also for going to Manny’s Music in New York, or sometimes finding a music store on the road and replenishing the crates of super heavy gauge strings that he used on his somewhat funky old Mosrites. He also had a lovely Epiphone solid body (stolen years later at the beginning of Cosmic Thing comeback) and a Sears Silvertone copy of a Dan Electro complete with amp and speaker built into the case. (They actually used the case amp on stage in the early days, setting it up and putting a mic from the PA in front of it just as a normal amp). Later he did have some Fender Strats and some yellow chunky off brand guitar he got somewhere.

Moe set up the drums and ran the sound from the house. We were a pretty tight two-man crew and had it down to every square inch in the truck utilized to its best potential - Moe was anal as hell but had also been around so he was a creature of the rock and roll environment. He told me from day one “there’s no down time in rock and roll,” meaning that after the stage is set and guitars strung and tuned and awaiting the group for sound check or after sound check, there was always something to do and no time to just wander off or not be working. There was always some gear to be checked, case to be struck and stowed, a cable to be taped down....on and on. And he was right.

Poster designed by B’s member Keith Strickland. Courtesy: Chris Rasmussen, Art Rocks Athens.

We would pack the rental truck and repack it at first, looking for the perfect pack regarding the cases and their sizes and shapes, but also the order in which they needed to come off the truck for the set up. We got to a point where we could breakdown and load out in record time and we had to because usually we had to drive an overnighter to the next city, check into a motel for 3 or 4 hours of sleep, maybe, and then get up and head to the venue, always arriving an hour earlier than the itinerary indicated. And do the whole thing: the load in , the setup, the restringing of guitars, the sound check, the non-down-time period before show time, eating crappy bar food in the beer and cigarette smoke ambiance of the venue while the band went out on their eternal search for vegetarian fare, the show, the break down and load out and we were off again, usually with Moe driving at first and me writing post cards to folks back in Athens and Macon. Sometimes I was so tired I would try to sleep under the furniture in the dressing room until Moe would find me. But it was great. The best job I ever had. And although I had volunteered to work for free, Ricky saw how hard I was working and told the band that I should be paid. I was already getting a per diem, so I thought I was getting paid.

We played clubs mostly, the odd college but also opened for the Talking Heads at bigger venues as the B’s and Talking Heads shared the same management. Standouts from those early days include : Club 57 in New York, The Exit Inn in Nashville, The Agora in Atlanta, The Iguana in Austin, U.C. Berkley with the Talking Heads in the middle of the day in front of student union (we parked the Ryder trucks back to back with a stage in between and used them as dressing rooms, The Greek Theater in LA, opening for the Talking Heads, and some crappy Chinese Restaurant by day that transformed into a rock club at night with a load in from hell up two flights of stairs.

As far as Pylon goes, I knew most of them from Art School or just Athens parties.

An early Pylon band photo from 1979 taken by Michael Lachowski in drummer Curtis Crowe’s downtown loft.

I never worked for them but saw them perform around Athens before we left town in fall of 79. I did go out to Nicky Generis’ place in the country one time where I played keyboards and Curtis Crowe played drums while Dana Downs sang and Nicky banged out power chords on the guitar. Dana was a little over served and ended up lying on the floor to sing and I was not that experienced in being in a band so I was not catching on to whatever Nicky wanted us to be doing. He would stop every few minutes and scream at the top of his lungs, “No, No, No! That’s not fucking right! It goes duna duna duna dum bam boom,” or whatever and we’d try again and he’d stop and yell some more. The more he yelled the wider the grin on Curtis’s face and the more incoherent Dana became and I kept thinking, “This sucks. I don’t want to be in a band.” Later that nucleus grew into the Tone Tones. I played piano but I was not really the performing type, that is to say I didn’t have confidence. The only other times I played with folks in Athens were jamming with the B’s in their Hull Street rehearsal space, just once (awesome!), and dropping by to visit Vic Varney and ending up jamming in his basement with him and some other cats. That’s it.

In the meantime, my good friend Margaret Katz had been going to check out a band called the Fans. We knew the keyboardist, Mike Green, from our dorm days at UGA. The first time I saw them at Rose’s Cantina in Atlanta, I was blown away. To actually know somebody who could write songs like that and make that kind of sound live. I was hooked. I would spend many days and some nights at their house on Seminole, either before or after one of their shows or when in town to catch other acts that came through. Those punk and new wave acts often knew their counterparts in other cities: it was a network, and people would come to the band house to either say “hey” or to crash. We first met Chris and Tina from the Talking Heads at that house, out on the front porch after The Talking Heads and Elvis Costello show at the Roxy in Buckhead. Some of Costello’s band showed up later, jammed with some of the Fans and ended up spitting at each other and nearly fist fighting for some reason. I guess it was punk.

After we had moved away to New York City, we still came home often to Georgia and to Athens. One time while visiting I went to the Caledonia to catch REM I had heard so much about. I thought, “Man, these guys suck.” Truly, they weren’t up to the standards of other acts coming out of Athens and Atlanta back then. Then, about 6 months later I saw them again and they were great. Shortly after that they began their journey toward world domination. I got to know Bill Berry and Mike Mills pretty well; both are from my home town of Macon and both were pretty down to Earth, talking about the Braves and such. I got to know Peter Buck some but not as well and Michael Stipe was a mystery for years, seemingly aloof. However, in recent years I have gotten to know him and like him a lot. But they started after we left town.

Once while visiting, we threw a party in the space that is now the Caledonia but was destined to be the 40 Watt Club for a while. Jimmy Ellison’s band played and Cindy Wilson, Paul Scales and others played a few tunes with them and then a band named Love Tractor made their debut. It was a big night.

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

I saw the B-52’s the first time they performed publicly, at the party on Milledge Avenue, Athens, Feb. 14th, 1977. The following weekend I caught them again at their second party performance in Athens at the residence of Teresa Randolph. I helped them roll up their rug and pack up their minimal gear in an effort to meet Cindy Wilson. Shortly after that we began dating. Eventually, they signed their major label deal and were going to head out on the road and relocate to New York City (their manager said you couldn’t be in a nationally known band and be based in Athens GA). In order for us to remain together, Cindy talked the manager into letting me be the one crew member that the hired sound guy would be allowed to have. I volunteered to do this for free even, to sweeten the proposition. The manager said “Sure, cheap labor, keeping one of the singers happy, two for one motel room, you’re hired.”

Moe, however, was not happy about that situation, the singer’s boyfriend going to be his crew. He called me up in Athens and tried to talk me out of it. He said I didn’t know what I was getting myself into (he was right) and that it would be the hardest thing I’d ever done (right again). He just couldn’t have somebody with no experience trying to do this when it would only be a two-man crew. I did the only thing I could do at that juncture. I lied. It was for his benefit as much as anything because there was no way that Cindy and I were going to be denied this opportunity, especially since it was already a done deal. I thought that I may as well make the cat feel better about it. I told him I’d played in bands in high school (true) and that I had changed strings on guitars (once in a blue moon if one broke, but it was a pain in the ass which was why I started playing keyboards instead - but that part I left out) and that I had set up drums (blatant lie) and after a while he softened up.

The beginning of the Athens Atlanta music scene represented a life-changing series of events for me and the very thing that was starting to happen unfortunately was the thing that took us far away. Fortunately, the people we knew and still know from those times are so special to us and I feel that no matter where those folks might be, collectively we are all still Athens. It's more than a place but a shared experience and aesthetic.

4. What are you doing in music now?

Well, I am an art Director/Graphic designer so I did not remain in the music field after my early roadie years, aside from an unofficial and unpaid position as guest list facilitator. I worked for years in advertising in NYC and Atlanta and designed and produced LP covers on a freelance basis for bands that included the Landsharks, Dreams so Real, Michelle Malone and Drag the River and years later designed a GoGos re-release of their first LP with additional booklet and bonus material. Also created graphic design for Cindy’s solo project, the Cindy Wilson Band, including press kits, posters, t-shirts and web site. I also designed the B-52’s LP covers for Mesopotamia and Bouncing off the Satellites.

These days, Cindy and I are still married, so I do kid duty while she goes out of town to do shows. Our kids are in bands, and have been since age 9. Their current act is called ARRAY. India and Nolan, our two kids, play bass and keyboards and sing and write songs in the group and they are rounded out by a few other teen aged kids who are all excellent musicians: Mary Frances Kitchens, who has played with Nolan and India since Mary Frances and Nolan were 9 years old, plays guitar and writes tightly crafted songs, Max Leech is their phenomenal self-taught drummer, and the latest addition is Andrew Weisburg on keyboards. I am their manager, crew chief, publicist, booking agent, graphic designer and driver of the car. The only thing I don’t help with is their song writing - I stay out of the creative.

5. Tell us one story you have never told anyone before about your time in a band or working in the scene.

Wow, that’s a tough one. Mainly because I’ve told so much that I don’t know of anything left untold. And if there was it would be for good reason and unlikely I’d tell it here.

Darryl Rhoades

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both, if applicable)

My first band, Darryl Rhoades & The Hahavishnu Orchestra (1975-78) was assembled in Atlanta but worked all over the country selling out venues in N.Y.C., Philadelphia, Austin and beyond. One of my favorite shows was a sold out show in a large concert hall at U.G.A. where Capricorn records came to see us and passed because we were too weird.

2. Name of your band(s) and your position in the band(s)

My first band was Darryl Rhoades & The Hahavishnu Orchestra (1975-78) and the next band was Darryl Rhoades & The Men From Glad (1985-88). I was the leader, frontman and songwriter.

I have been a drummer/songwriter/frontman since 1967 where I played all the Atlanta clubs with "The Celestial Voluptuous Banana".

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

I think playing UGA, Between The Hedges (a small nightclub in the student activities building, Memorial Hall) and the 40Watt Club always felt like home. WUGA played a lot of my material anytime I came out with a new recording

4. What are you doing in music now?

Currently, I am doing one man shows (comedy), writing an autobiography and working on my 13th CD. I’m also involved with four other songwriters and about to go into the studio to start working on a group recording.

5. Tell us one story you have never told anyone before about your time in a band or working in the scene.

In 1977, I was invited to perform on the WTBS show “James Brown Future Shock” with my band, The Hahavishnu Orchestra. We were known as a theatrical satirical group that featured dancers, backup singers in drag and usually numbered at least ten members on stage at any given time.

Our set on Mr. Brown’s show was shot during the day with everyone wearing pimp clothes and I made my entrance busting thru a perforated record drawn on a large sheet of butcher paper where I met two dancers that were tricked out in street ho threads. The band was vamping when I grabbed the mic and started singing our underground hit, “Suicide,” which was a dance song about how to kill yourself. James was watching us and later I was told by one of the camera men that James Brown was baffled and didn’t understand these crazy white people singing about killin’ yourself to a dance step. He reportedly turned to the camera guy and said “Issat some kinda of joke or sumphin”. I stuck around to see him do the intro and laughed as he struggled to say the band name. He eventually got it close enough when he said “Darryl Roe and the Hahavishnu”. It aired on Dec. 31, 1977.

youtube

Regrettably, James Brown's intro and outro to our appearance was not put on the video copy they furnished me.

Kevin Dunn

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both, if applicable)

Inasmuch as my Atlanta band of the epoch -- v. (2.) infra. -- contained one Athenian, whose presence in the lineup resulted in a substantial number of the art department's student luminaries and their circle attaching themselves to, nay, creating the group's sociostylistic ambit, that contact in turn initiating a circulation of reciprocal influence that I flatter myself persists to this day, I'm gonna say both.

2. Name of your band(s) and your position in the band(s)

The band was the Fans. I was the guitarist and second-string Komponist; sang mostly backup except on my own tunes. The other personnel were: Alfredo Villar, principal songwriter, lead singer and bassist; Russ King, drummer; and Mike Green, the above-cited Athenian, keyboards.

Kevin Dunn

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

V. (1.) supra. When, in 1975, my very old friend Harry DeMille began the association with Danny Beard, whose links to Athens were legion, that would lead to (among other things of well-documented moment) the creation of the music emporium Wax 'n Facts in Atlanta's Little Five Points district, the Fans were in desperate need of a simpatico keyboardist. Danny recommended Mike, he being possessed of considerable avant-garde cred, as a plausible candidate. The recommendation panned out, Mike joined the band, and the bi-urban connection was forged in train. The band was holed up on Seminole Avenue in Inman Park, in what was then a desuetudinous two-story yellow-brick house from the neighborhood's heyday in the 1920s (it's quite nice now), and the art party raged on within the ramshackle hulk's walls pretty much nonstop for three years or so.

4. What are you doing in music now?

Playing stringed and fretted things, either solo (lots of ambient loops, and Middle-Baroque repertory on original instruments) or in the context in divers aggregations, for no money; same as it ever was, as the poet would have it. I released a solo album in 2012, The Miraculous Miracle of the Imperial Empire (kevindunn.bandcamp.com). Having within the twelvemonth decamped from the ATL to the Classic City to get married, I am with my new bride Heli, my intermittently-resident son Malcolm, and assorted other players investigating various configurations of material and approaches thereto.

5. Tell us one story you have never told anyone before about your time in a band or working in the scene.

I being both garrulous and repetitive, I doubt any such anecdote, at least as qualified, exists. I'll instead share with you a top-of-mind bit of rue: it is a permanent source of professional regret to me that I was during the sessions for the B-52s' DB Recs single unable in my capacity as what I like to call "production sherpa" to persuade the band either to deploy an envelope follower-ring modulator combo on a doubled track of the descending guitar figure on "Rock Lobster" or to retain the original Farfisa bass track with the lacuna effected by that one blown analog oscillator on "52 Girls." Pity, really. If they'd just taken my advice, I'm sure their career would have fared so much better LOLLOLLOLLOLLOLLOLLOLLOL

And that's all I got. Mwah.

Robert Croker, The Fans, and the Drongz

One of the most influential teachers in the University of Georgia Department of Art was Robert Croker. His art education began at age 15 at the High Museum of Art. Before coming to UGA, he received an MFA from the University of Arizona in 1966. In his words, “Lamar Dodd rescued me from oblivion” at LaGrange College when Dodd recruited Croker to teach drawing and painting at UGA.

Credt for all drawings in this section is as follows:

Artist: Robert Croker (American, born 1939) Sketch from Notebook Medium: Graphite on paper Credit: Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; Gift of the artist in memory of Margaret Katz Nodine

During his tenure on the UGA campus, Croker taught Introductory Drawing for seven years. He became a major influence on his students (Including Pylon bassist Michael Lachowski) through his innovative teaching techniques, and in his last year at UGA, his independent study classes and individual critiques sometimes lasted late into the night.

Total immersion in art was the rule, and the art building was open 24 hours a day to accommodate the prodigious amount of work that was being produced.

Part of the discipline – if it could be called that – was that students were encouraged to make drawings (drongz) everywhere they went: — restaurants, bars, and night clubs were favorite places to make some of the 100 drawings that each student was expected to come up with each week.

Croker drew everywhere he went as well. The drawings seen here are from two of his sketchbooks, which he donated to the Georgia Museum of Art in memory of Margaret Katz-Nodine, one of his most talented students. Along with being a gifted artist, Katz, as she was known in those days, was also a “living, breathing part of the [Fans],” according to Croker.

Used with the permission of artist Robert Croker

This particular set of “drongz”, as Croker calls them, came from The Fans performing at Rose’s Cantina in Atlanta, and CBGB’s in New York City.

Doreen Cochran

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both):

Atlanta

2. Your connection to the music scene:

The Brains. Band coordinator

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

When the Brains played with the B 52's first time. You were there!

4. What are you doing in music now?

Nothing in music now.

5. Tell us one story you have never told anyone before about your time in a band or working in the scene.

I told my friends about this and they said what story haven't you told? Well, really the story I haven't told is that I am not as knowledgeable in the music biz as everyone thought. I just knew I liked the Brains and I could organize and sell them. I was flattered and just didn't let on.....

An addendum to Doreen’s answers from Maureen:

Doreen was one of the central figures in the Atlanta music scene, in part because she managed the Brains and ran the Brains’ fan club, which was one of the best organized fan clubs going at the time. She was also important because she was a woman doing a job that most women were not given an opportunity to do. I managed the B-52’s and she managed the Brains, so we always presented a united front. Her claim that she didn’t know what she was doing doesn’t hold water with me, except for one thing. We all walked through uncharted territory. The only thing we had that set us apart from the rest of the bumbling idiots was that we had each other. Athens bands and Atlanta bands supported each other and shared information to a degree that would be unthinkable today.

I think the show with the B’s that Doreen refers to here was at the Downtown Cafe in Atlanta. I remember taking a walk with Tom Gray after sound check, and he told me, “Maureen, I have written a song.” His words were full of wonder, and I knew that whatever this new song was, it must be something really special. That night, the Brain’s played Tom’s new song: Money Changes Everything. It was the song that catapulted Tom and his band into the fame stratosphere when Cyndi Lauper recorded it three years later.

Video: Tom Gray performing Money Changes Everything with another epic Atlanta band, the Swimming Pool Q’s, January 28, 2007.

Glenn Phillips

1. Music scene you were in (ATH or ATL, or both, if applicable)

Throughout my 50 years as a musician, I've been based in Atlanta and played Athens countless times as well.

2. Name of your band(s) and your position in the band(s)

I was a founding member of the Hampton Grease Band in 1967, as well as one of the band's two principal songwriters (myself and Harold Kelling). When that group broke up in 1973, I started playing and recording under my own name and now have eighteen albums out, including two with Jeff Calder (of the Swimming Pool Q's), under the name Supreme Court. I've also recorded with Cindy Wilson of the B-52s, Pete Buck of REM, Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead, and many others.

The Hampton Grease Band

3. What was the beginning of the Atlanta and Athens music connection for you personally?

The Grease Band was based out of Atlanta and started playing Athens in the late '60s. That continued for me throughout the '70s and '80s, and Cindy Wilson and I did a show together at last year's AthFest. I've always thought of the two cities as being creatively connected, and I feel incredibly lucky to have ties to both.

4. What are you doing in music now?

My first solo album Lost at Sea was recently rereleased as a 40th anniversary double-vinyl album on UK label Shagrat Records (it was originally released on Virgin Records), and this fall they're putting out a live album of my 1977 show at London's Rainbow Theatre. I'm also in the midst of recording my next album of new material and still playing out live.

5. Tell us one story you have never told anyone before about your time in a band or working in the scene.

I've never told the whole story of how and why the Grease Band started the free concerts in Piedmont Park in the spring of '68. Although we’re known today for the eccentric music on our double album Music to Eat, when we first started out in '67, we thought of ourselves as a blues band. This was right before the blues explosion hit the South, although at the time, soul music was quite popular here, like Motown and James Brown.

We considered ourselves blues purists, though, and would never play anything as commercial as James Brown, so when we played one of our first jobs at a high school dance, the reception was not enthusiastic — we cleared out the room. We figured the high school crowd just wasn’t hip enough for us, although it may have also had something to do with the fact that we stunk: We were just starting out and most of us could barely play our instruments.

In any case, we decided to take our music where we thought we’d be appreciated, to an African-American club called the Poison Apple Room. Atlanta was still a pretty segregated city back then, but the owner hired us anyway. He was hoping to expand his business by drawing some white kids to his club and saw us as a possible way to do that. I think he also felt sorry for us — we were like dogs at the pound looking for a home, and he took us in.

Once we started playing for the club’s audience, though, our dreams of acceptance collided with reality. Unfortunately, they knew the difference between the real thing and a group of oblivious suburban white teenagers. Nonetheless, they politely tolerated us, although one member of the audience decided to give us a music lesson. He walked up to the bandstand while we were in the middle of a song, reached into his coat, pulled out a gun, and pointed it at us. Then he made a request, "You play some James Brown or I'm gonna blow your fuckin' head off."

As I mentioned earlier, we’d never played a James Brown song in our lives, but it’s amazing how fast you can learn to do something when there’s a gun pointed at you. We launched into the worst ever cover version of "Popcorn," and from that point on, the club's owner would greet us each night at the door with, "You boys need to sell those goddamn guitars and amplifiers, and buy you some pussy."

The reception we'd gotten at the high school dance and The Poison Apple Room got me thinking we might want to find some other places to play. I had noticed there was an electrical outlet in the Piedmont Park pavilion, and in the spring of '68, I took a clock radio down there and discovered it was a live outlet. The following weekend, the band set our equipment up on the grass, plugged in, played, and crowds of hippies started gathering around us. We asked no one for permission nor did we apply for any permits — prior to our makeshift concerts, no electric bands had played there before, so this was uncharted territory, but we kept it up every weekend, and by the middle of that summer, the shows had grown to include many other great Atlanta bands. By the following summer of '69, we were doing shows there with the Allman Brothers and The Grateful Dead.

vimeo

Great things have strange beginnings.

Video: This clip features Cindy Wilson of the B-52s with Glenn’s band doing "Give Me Back My Man," which seems perfect given the subject of the Atlanta and Athens music connection: https://vimeo.com/170252139

The featured image of the B-52’s at the top of this story was photographed by Terry Allen and is used with the kind permission of the photographer.

(This article appeared on Richard Eldredge’s web site, EldredgeATL.com, as part of series of articles on Athens, GA curated by Vanessa Briscoe Hay.

0 notes

Text

Eulogy for Margaret Katz by Robert Croker

Eulogy for Margaret Katz Nodine (Music) Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Do we do a lot? Dowedoalot?Dowedoalot?Dowedoalot?Dowedoalot?Dowedoalot?Dowedoalot?Dowedoalot?Dowedoalot?Dowedoalot?Dowedoalot?Dowedoalot?Dowedoalot? Do we…?! DO WE…?! DOO WEE…? -- "Ekstasis" (Alfredo Villar)

We did a lot. Katz did more than most, and if you were to do a lot, too, you had to keep up with Katz. So I asked myself: What did we "really" do when we did a lot?

We smeared colored goo onto cloth. Or burned wood or colored schmutz onto pressed fragments of trees or cotton fibers or animal hides. Sometimes we mixed the schmutz with water or milk, or eggyolk. We scratched gouges in metal or submerged it in poisonous liquids; or we smudged more grease onto a flat rock before pushing the greasy mud onto paper. Or we pushed strings through one another on a huge awkward machine designed for the purpose, or tied them together somehow. We pushed a pin into a glorified shoebox to let light in. We heated metal until it melted, then poured it into sand or wax and let it cool off; or we cut it into pieces with a torch, then put it back together with the same torch. We attacked defenseless rocks with hammers and sharp instruments. We slopped real mud onto a wheel, stuck our hands in it, and spun it around in circles, or poked and pried it until we could put some more mud on it and stick it in an oven. We pushed carbon dioxide through a reed into a hollow tube, when we could more easily have expelled it by yawning, or dragged a horse’s tail across a cat’s innards, or beat a dead animal’s hide with a stick, or flailed at strung pieces of wire and jumped around. We dressed up funny and jumped around on the floor in an unnatural manner while other people pushed, dragged, beat and flailed. We dressed up funny and walked onto a floor, saying words that somebody wrote 600 years ago in a language nobody speaks any more, or in a language of our own that nobody speaks yet. We strung words together in patterns that don’t even fill up the page. We did these things repeatedly for extended periods of time. We needlessly, even heedlessly, proliferated entities. (A-and screw you, Billy-o Ockham.) We expended disproportionate amounts of energy in doing all these things.

We stayed up long past bedtime, eating, drinking and smoking things that were bad for us, laughing immoderately, passionately arguing about things we didn’t remember when we woke up in the morning (or the afternoon), maybe someplace we weren’t really sure we’d ever been before or how we got there or who we were with. We lived in places that would horrify our relatives, and probably the Fire Department, too. We were very carefully careless in our modes of comportment, dress and address, and in the matter of regular coiffeurs. We regarded hard-and-fast rules as tentative suggestions, and chronological time as an amusing concept (except for the occasional 4’33” interval). And when we got done, we called the results art, music, dance, poetry, philosophy, and theater. And people believed us. (A-and -- more importantly -- we believed it ourselves.)

Margaret Katz-Nodine was a diligent, inspired artist who drew and painted every day. She attended the University of Georgia, where Robert Croker was her drawing teacher. This is a snapshot of the arts community in Athens, Georgia, circa 1975.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Klaus Nomi at Hurrah! 1979

0 notes

Text

From the Soho Weekly News, 1979 KLAUS NOMI photographs by Julie Jacobs interrogation by Maureen McLaughlin and John Beal Who is Klaus Nomi? A creature of any state, sex or sensibility you choose. The astral plane where Mrs. Miller and Jobriath embrace. A pale, shimmering genius - or a complete fathead. The real Eight Wonder of the World - or a tragic slip in Mother Nature's busy assembly line. A painted bird, singing sweetly in soaring flight - or a mildly amusing bizarro propped up by good musicians (including at his few recent live performances, Kristin Hoffman and Joe Katz) Read on, dear reader, and judge for yourself! The Editors

"When I decided to wear make-up, it was very difficult because for a male person, wearing make-up is a very strange thing to do in the eyes of the masses.... Actually, it began when I was a child in Germany. I had a good time going to the opera at night as an extra onstage, and I enjoyed doing make-up there because I could do it without being bothered. I've always felt very much related to the theater and music, yet I never found a way to do operatatic material seriously."

"Some people think I'm not human. That's why I can't eat, can't have sex, I can't burp, I can't do anything really."

"My mother visited me two years ago, when my image was very similar to today's image. She was so shocked. I had black fingernails and black lipstick, and she said "You look like the Devil - I can't believe it." I said 'Mother, I AM the Devil!' That was enough for her."

"I always loved rock n' roll, actually. For me, the biggest name in rock n' roll was when I was twelve: Elvis Presley. I bought an EP, King Creole. I hid it in the basement to make sure, but my mother found it. She went to the record store where I bought it and exchanged it for Maria Callas operatic arias. Well I was very agreeable to that too. So I got into that, but every time I bought a rock n' roll record, at the same time I bought a classical record. That was the point of my confusion because I like each as well as the other. So I was constantly freaking out."

"I want to be in a lot of movies, and I'm working on a film myself. It's a long term project. I want to take my time, because I want to make it real good. I have the basic idea for a film in my head - Salome. I want to play the title role.

"I saw Maria Callas once, and I always had a vision to met her. In Germany, there is a custom on New Year's Eve. You melt a certain metal over a candlelight, and when it becomes liquid you pour it into cold water. Something very bizarre comes out of it. The idea is that you take it and judge for yourself what it could possibly mean to you. This shape looked like two people facing each other, and of course it was Maria and I. Well, three months later it was announced that she was to come ot the small town where I lived to give a concert. It was perfect - of coure I wa there. And of course, I jumped onto the stage and was facing her as close as I thought I would be. I caught a glimpse of her eye, and it was like a fire burning in me. I almost fainted. The next day, I went to see a vocal teacher and started to sing professionally, and every time I am succesful in anything, in honor to her I play one of her records."

Klaus Nomi was an unusually focused person who had one of the most magnificent voices I have ever heard. The first time I saw him onstage at Hurrah, I was floored by his performance. John Beale and I interviewed him for the SoHo News, I wrote up the interview, and Julie Jacobs took the pictures.

One of my fondest memories of this experience is having a serious discussion with Klaus about makeup. He shared numerous tips for painting one's face artfully. The day after this interview, I went to the Capezio store in the West Village and bought a tube of FuchsiaRistic Stagelight lipstick, along with metallic blue, gold and copper eyeshadow.

Unfortunately, Klaus was a casualty of the AIDS epidemic. He died in 1983.

I found this article here: http://www.psychotica.net/evb/nomi/sohonews.html

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Another from my collection of notes on tiny pieces of paper, circa 1978.

0 notes

Text

Art Rocks Athens

In an effort to make a reliable record of our history, my friends and I are presenting a series of events entitled Art Rocks Athens. This is a historical retrospective of art and music in Athens, Georgia from 1975-85. For more information, visit our website, http://www.artrocksathens.com or join our Facebook group: https://www.facebook.com/ArtRocksAthens #ARA2014

0 notes

Photo

In addition to making a mean daiquiri, Leslie Michel and I perfected the recipe for making grain alcohol punch in a claw-footed bathtub. Everything is on this shopping list except the grain alcohol: we added either four or eight gallons of alcohol: not sure which. The secret to a good bathtub punch is to get the freshest fruit possible, peel and chop it into bite-sized pieces, and then soak the fruit in the alcohol for, oh, about a day, before adding it to the punch.

P.S.: Don't worry about the Clorox: it is used to clean the tub before the punch making begins.

0 notes

Photo

John Seawright at Home

Photograph by Terry Allen

1 note

·

View note

Text

John Seawright's Death

John Seawright was a stellar human being: a poet, a lover, a drinker, a scholar, and a historian among other things, he conquered everyone he met with his towering physical presence, devastating intellect, and charismatic personality. He was one of the forces that stirred the Athens creative cauldron from which so much art and music emerged. This is the story of his death.

Once again, I have left in the grammatical and usage errors. Apologies to Rodger Brown for the misspelling of his first name.

I am writing this for everyone who could not be in Athens over the past week. It is now Friday, May 18, 2001. John Seawright's body was discovered last Thursday, May 10, at his house on Meigs Street. This is not going to be a polished piece like the obituary I wrote - once these words are down, I don't even know if I will ever read them again. However, I want to try to give y'all the flavor of what the past week has been like. There is no way that I could possibly capture every bittersweet moment, but I will try. These are my impressions.

It was Thursday, May 10, and I had to go to the post office. Since it was a pretty day, I decided to walk downtown. I do this maybe once a month. My usual route takes me from Park Avenue to Prince Avenue, then to Pulaski, then to Hancock Street, where the post office is located. I started off down Prince about 3:00 p.m., but when I reached Milledge Avenue, my body turned right. "This is interesting," I thought. Something was pulling me down the street. It occurred to me that I needed to see John Seawright, so maybe that was it. I started to turn at Hill Street, but no. I had to turn down Meigs.

When I got to John's block, I saw four police cars and a crime scene van clogging the street. A lone detective was talking to Jerry Ayers in front of John's next door neighbor's house. I thought that maybe the neighbor had had a break-in. Since there was such a scene, I thought that I would continue on to the post office and stop in to see John on the way back. Just as I got to John's front door, four police officers came bursting through the door wearing dust masks covering their noses and mouths. At that moment, I knew that John was dead.

I turned on my heel, and went back to Jerry and the police officer, interrupting their conversation. "Jerry, what's happened to John?"

"He's dead, Maureen. Jennifer and I found his body about forty-five minutes ago."

Even though I already knew, Jerry's words hit hard. I felt like someone had heaved a concrete block at my chest. Jerry pulled me close, and we stood in the middle of the street, sobbing. After a few moments, he looked away and said softly, in a voice filled with regret, "It wasn't supposed to be like this for John." I can still hear his voice, gentle and sad, and see his stricken face.

One of the detectives pulled me away to be interviewed. She started asking me a series of bodacious questions, each prefaced with, "I'm sorry to ask you this, but…"

"Did Mr. Seawright have a drug habit?"

"The only drug I ever saw him use was alcohol."

"Did he have a particular lady friend who might have been jealous?"

"John had many women friends, and none was jealous, as far as I know."

"Did he maybe take up with a loose woman in a bar, someone who might have come home with him and set him up to be robbed?"

At that point, I realized that this woman should be home writing mystery novels instead of on the streets detecting. She was determined to find some dark place in John's life where she could poke a stick, and hit a nerve. I told her that I understood that she had a job to do, but no detecting was needed here. I was sure from the outset that John had died of natural causes. I knew that it was brain aneurysm. I don't know how I knew, but I knew.

Jerry came up to me, "I have to go home. I have to go home right now."

He turned and walked towards Harris Street. From the opposite direction, a gray Coroner's van navigated up the street and turned into John's yard. My first thought was that I should stay. Some one of his friends should be there to see John leave his house for the last time. I had to decide: did I want my last memory of John to be hugging him in the aisle at Kroger, or coming out of his house on a stretcher? I simply could not bear to think of him in a body bag or metal box.

I went on to the post office, mainly because I was carrying two bulky manila envelopes, and it was faster to mail them than to take them back home. Then I felt compelled to go back to Meigs Street. By the time I got there, the gray van carrying John's body had left. Betsy Dorminey was standing across the street from John's house, talking to Detective Chris Guest. I remembered him from the Jamorio Marshall murder trial the year before, where I worked for Jamorio's mother, Vernessa. Neither of us mentioned it, but Det. Guest treated me more like a colleague than a citizen.

"I'll tell y'all, I am ninety-nine percent y'all's friend died of natural causes. I will be very, very surprised if it turns out to be something else." That made me feel better.

Betsy mentioned that John had written for the Flagpole, and Guest remarked that he knew he had seen "the name of Seawright" somewhere before. He also said that he was sure he must have read some of John's work, he just couldn't remember it.

"I'm sure y'all understand, since this was an unattended death, we have to do an autopsy." That was the second time that day I had heard that phrase, an unattended death. The first detective had also mentioned it when I asked her if there was going to be an autopsy. How could anything having to do with John Seawright be unattended? He was the best attended person I ever met. People stood in line to talk to him, to walk with him, to listen to one of his stories across the bar at the Globe, or from the corner stool at the Manhattan.

Betsy invited me back to her house. By that time, I was feeling very, very lost. We walked up the front steps of her house and into the hall where Blair was standing. He must have just gotten home from work. Betsy told Blair the bad news. He could tell from looking at our faces that something was wrong.

"Blair, John Seawright is dead." Blair stepped back and all of the color drained from his face. We went into the kitchen and talked for a few minutes, and at that moment, the notification process officially started. I knew that I would have to go home and start calling people. I couldn't call them all. Where would it begin? First, though, I wanted to check on Jerry Ayers. Blair wanted to go with me, so we walked around the corner to Harris Street.

When we got there, a tall young man with dark spiky hair with chunks of dyed blonde in it was standing there at the front walkway. I told him we wanted to see Jerry. "Oh yeah? And how long have you known Jeremy?" I smiled, and exchanged sideways glances with Blair.

"About thirty years, more or less. He'll want to talk to me. I was there on Meigs Street," I said, my voice shaking with emotion.

"I'll go and see if he can talk to you," he said chastely, "He's pretty broken up."

We entered the house and went into Jerry's living room/kitchen, where he was seated on the sofa. All he said was my name, and we all started crying again. The telephone started to ring. The young man with the spiky hair picked it up.

"Let's go out on the porch," Jerry said.

We sat down, and I suggested that maybe we should have a meditation for John, any excuse not to be alone. When Cynthia died, I did a sitting for her. We decided not to organize anything, and just wait to see what happened. It was too much to think about at the moment. Jerry went to answer the phone, and Kai, the tall man we had spoken with in the street, said, "I know that it couldn't have been suicide, because if John had wanted to kill himself, he would have written a note."

I laughed, "He probably would have written a book."

Kai continued, "He would have left a big long note absolving absolutely everybody and anybody from feeling any guilt. That's just the kind of person he is."

Jerry came out on the porch with the phone. He handed it to me, and I spoke to Chris, who said he was on his way up to see Ryan and Polly, John's parents. By that point, I was shaking so hard, I could barely speak. I realized that I needed to get up and walk.

We stood on the sidewalk in front of the house and said our goodbyes. Kai apologized sweetly for being so abrupt when we first appeared. We understood: he was feeling protective because Jerry was so vulnerable.

Jerry and Blair both offered to take me home, but I declined. I decided that the first person I would tell was Mike Marsingill, the minister at Young Harris Memorial Methodist Church. Cynthia's memorial service had been held there, and I thought that John's probably would be, as well. Just as I got to Mike's house, he was pulling out of the driveway to take his family to dinner. I could have flagged him down, but decided to let him eat in peace.

When I got home, the first person I called was Diana Crowe. I knew that she could spread the word to a lot of people, and I wasn't sure how many of these phone calls I would be able to make. Next, I called Jefferson Holt, who was in a tizzy.

"Hi, Maureen, this phone isn't working. I hate this phone. Let me call you back on a real phone." For whatever reason, he never returned my call. I moved on to Vanessa Hay next, but got her voice mail.

Michael Lachowski was next on the list. For so many years, John and Michael and I were a part of the same group of friends. I saw both of them every day. Michael is still high up on the Athens grapevine, and knows many more people than I do now. When I delivered the news to him, he flooded me with his characteristic warmth: "I can't thank you enough for thinking about me. It means so much to hear this from you…" Love and support. That was just what I needed then.

Then I called Leslie Michel in California. Leslie delivers quip after quotable quip at about the same rate of speed as a jackhammer. Here is a snippet of her peroration: "Omigod, I am so bummed out about this. What I want to know is: why did he want to check out so early? When somebody leaves the planet so far ahead of schedule, there has to be a reason for it. When you've been in the floral industry as long as I was, you've seen everything. Obviously he didn't know what a tremendous effect he had on the lives of all the people around him, and even on my life. I will always think of him on Barber Street, eating pecans. And he was a writer. I will always remember him as a writer."

I told Leslie that I thought some part of John just didn't want to live any more without Cynthia. He did not have a death wish; he was not suicidal. He just wanted to go home. Now I'm thinking: maybe his brain just flat wore out. I don't know. I kept waiting for John to publish a book, thinking that he would turn a corner the day that happened. I left Leslie by asking her to call Mike Mills. He would want to know, and the phone number I have for him does not have voice mail.

After my whirlwind conversation with Leslie, I called Cynthia Kutka, formerly Flack.

"Cynthia, I have some bad news…"

After several wobbly minutes of relaying the sad information, I asked Cynthia to call DeLoris Wentzel. I figured that if everyone I called made one call, Athens would know in about an hour, and the world, maybe, by morning.

The phone calls went on. I called Jim Herbert, and found out that he was in Cortona. I sent him a fax via the art department, to be re-faxed to Italy. Herbert is going to be sorry that he could not be here.

Mike Marsingill got home from dinner. He said that he would call Polly and Ryan, and offer the church for use for the memorial service. LaMurl Morris, the music director at Young Harris, is a close friend of Ryan's, so Mike volunteered to call her. We would be needing her services.

I called Keith Strickland, mainly so he could get in touch with Jerry and offer him his support. He did not return my phone call. He was probably out of town and not accessing his voice mail.

Next, I called Jimmy Paulk in New York City. Paulk and I have been friends for thirty years or so. On one trip to New York, we had dinner with Sam and Tara, John's brother and sister-in-law, at Ray's Pizza in the West Village. I thought that it would be nice for Sam and Tara to have someone's support in The City. No one answered at his house, so I left a message.

I took a break for dinner. I went to the Taco Stand, since I wasn’t in the mood to cook, and it was getting late. I wasn't sure I could eat, but I needed a few minutes to rest away from the phone. While standing at the counter, waiting for the food, I saw John. He was in front of the side door, leaning with one elbow propped against the wall, and smiling that mischievous smile of his. I thought I was making this up. I looked away, and looked back. He was still there. I went up to him, and said under my breath, "Go away. I came here to get away from you. Go away." I looked away again, and looked back, and he was gone. In retrospect, I think I was mad that he would show up in a public place where I could not talk to him without looking like an idiot.

When we got home, I called Pete McCommons, editor of the Flagpole. As soon as I heard his voice, I started crying again. He said, "All of Athens is in mourning."

"Pete, can I write John's article?"

All he said was, "I wish you would."

Neither of us could talk, so we hung up.

The phone rang. It was Vanessa Hay. When I gave her the news, she recalled the first two times she met John. One was at a party in Mell-Lipscomb where he sat in the corner, wearing headphones, listening to the Velvet Underground. The second was at a Halloween party in the dorms where John appeared in a black cocktail dress and blonde wig. I have always wondered: where did a man nearly seven feet tall find a cocktail dress in his size? Even a person suffering a profound sorrow can wonder.

About 10 p.m., I called Sam. He picked up the phone on the first ring, his voice so heavily laden with grief that it broke my heart all over again. He told me that when they first told him, he started hyperventilating, and that for the first little while, whenever someone mentioned John, he would start hyperventilating again. Now he could talk. Sam told me, "Now that John is gone, I'm never going to see anything or feel anything the same way again." We spoke of other things: of the autopsy yet to be done, of funeral plans yet to be made, of a memorial service not yet scheduled.

When I got off the phone with Sam, I was glad that he had taken the time to speak with me. Both he and John learned how to be ministers at a very early age. Neither of them would ever turn away a living soul, regardless of how they were feeling at the time. That was about all that I could take for that day. I thought about trying to find Jerry, to see how he was doing, but I was too tired. By 11 p.m., I had fallen into an exhausted sleep.

Friday morning, I got up and started writing. I wrote about John's parents, and about his relationship with Sam. I recalled a road trip I had taken with John one lazy summer afternoon, and of the people he had introduced me to in Washington, Georgia. After about three hours, the phone rang. It was Pete. "Maureen, I was just wondering. How long is this thing that you're writing?" Pete knows that I sometimes forget about length restrictions, my not being a real newspaper writer. He told me that he needed 1,000 to 1,200 words, max. I got off the phone and looked at what I had written. So far, I had 705 words, and I had just gotten John to his first day at UGA. This would never do.

Vanessa Hay knocked on the door. She had come over for coffee. As usual, I was out of milk, and she had brought some with her. We sat on the back porch and drank our coffee. To deal with our serotonin deficiencies, she had brought a box of Godiva chocolates.

I told Vanessa about my article, and that I decided it had too many facts in it. It would be impossible to write the encyclopedia of John Seawright. I was going to have to take it in a different direction. We also talked about the people we had contacted.

Vanessa had e-mailed Sandy Phipps, up in Vermont. Sandy is a gifted photographer, and a dear friend. She wrote Vanessa back with the story of how John kept showing up at her house after her best friend Carol died. He didn't think that she should be alone.

Finally, after all these years, Vanessa gave me a full account of Cynthia and John's wedding. John had told me about it my very first night back in Athens, but it was still too soon after her death for details. Vanessa described how beautiful Cynthia looked, and how she kept the whole assembly waiting because she was too overcome to walk down the aisle. When she finally appeared, she had to be supported by her mother on one side and her father on the other. The whole Seawright family was beaming. Cynthia was carrying a bouquet of sunflowers, and wearing a long green linen sheath. With her long red hair in curls, Vanessa said, "She looked like a mermaid rising out of the woods." I continue to think about that image when I get too sad.

Vanessa and I decided to go and get some tomato plants. "It's always good to plant something when somebody dies, even if it's just a bunch of scraggly old tomato plants," she said. We went over to Cofers and got three kinds of tomatoes and a pepper. I went back home and tried to write some more.

The phone rang. It was Jimmy Paulk. When I told him what happened, he told me that he and Sam and Tara had gotten to be "quite good friends." In fact, at that moment, Sam had a showing of drawings at Jimmy's office in SoHo. If Sam and Tara needed anything, I knew that Paulk would be there for them.

I went back to my Powerbook, and re-read what I had written. How am I ever going to get this magnificent man's life distilled into a thousand words? Too many facts. I had to get rid of the facts. I craved companionship, but I was so emotionally exhausted, I didn't think I could deal with seeing anyone else. I knew that there were other people to call, but I was not going to break the news to another soul.

Then I called Rhett Crowe, and asked her if she had any good John Seawright stories. "Why," she asked, "is he going somewhere?" Oh, Lord, I had to do it again. I was certain someone would have phoned Rhett. I am never going to call anyone else as long as I live.

The rest of Friday and most of Saturday passed, with me sitting in front of my computer screen, thinking, "What am I going to write?" Anything less than the best simply would not do. John was always my most exacting critic. I never saw him happier than sitting with a page of typescript and a pen in his hand. He was the only person whose opinion really mattered when it came to my writing.

On Saturday, I spoke again with Cynthia, or Chynthia, as she is known to her friends. David Gamble and DeLoris and Ken Tapscott were at her house. Chynth and her husband were leaving town Sunday morning to go to Denver, so she and Gedas would not be in town for any of the events of the next three days. We talked about going to the funeral home: we both wondered if the casket would be open, in the true Southern tradition. I am afraid of small dead animals. How would I react to a great big ol' hulking dead John Seawright? I could not imagine.

At the same time, I did not want to miss a minute of the proceedings of John's Homecoming. Even though I knew it would be hard, I wanted to be there for everything. In the future, I did not want to have to look back on those three days and say, "I wish I had…"

Ken said in the background that there was No Way he was going to the funeral home. I said that I was going. I called Vanessa, knowing that she would be up for the trip to Toccoa. Since she is an oncology nurse, she deals with death all the time. A little funeral home time was not going to bother her.

Then I talked to Paul Nelson. "John is one of the lucky ones," he said. Paul wanted to go, and he needed a ride. He said that he would check around and see if anyone else needed to come with us. He mentioned John Jack, John's cousin, whom I had not seen in at least fifteen years. By the end of the evening, we had determined that Paul, Joe Bennett, Vanessa and I would be riding together to the funeral home on Sunday.

I went to church at Young Harris on Sunday morning, and cancelled the young children's group I was supposed to be leading that night. The children were puzzled, because I never cancel their time together. All I could tell them was that my friend and died, and I was too sad to come to Pathways.

At about 5:45 p.m., Vanessa came to pick me up. Then we went over to Harris Street to pick up Paul and Joe. Almost immediately, the stories started coming out. We began by making a list of everyone each of us had talked to in the past twenty-four hours, and of all the people we had no idea how to find. John Taylor had called Paul. I had tried to call Taylor, but the number I had for him did not work. I was glad he knew.

Many of the people we wondered about were women. John loved women, and he had a very impressive list of women friends. We mentioned Megan, Sam's old flame. I knew that I could find her, but until that moment, it hadn't occurred to me to call her. There were the art girls: Margaret, Phyllis, and the rest. I had spoken to Phyllis in New Mexico a week earlier, but didn't have the heart to call her now.

We arrived at the Acree-Davis funeral home, a modest pink brick building, and the process of carrying John home officially began. As we rounded the corner from the parking lot, I saw Ben Barks. He looked sad and lost. I gave him a hug as we continued in. So many, many people were standing in line. I saw people from Young Harris UMC, people from my past, and people from today. The atmosphere was almost cocktail party-like. Most people were standing in a receiving line to pay their respects to John's family. Others were standing small groups, talking. Some conversations were strained, but most of them were easy. Wallets were being pulled out and pictures of children were being displayed.

From our position in the back of the line, I kept trying to see if the casket was open. I couldn't tell. That made me nervous. Keith Bennett came up and showed us pictures of India, his and Cindy Wilson's daughter, and their baby. He described in graphic detail how Cindy had to spend the entire third trimester in bed because of a problem with her uterus before the first baby was born. Vanessa knew what he was talking about, but when they got to the part about sewing up the uterus with the second baby so Cindy wouldn't have to stay in bed, I kinda zoned out…

The line moved from the foyer into the viewing room. It was an old time living room - a parlor with couches, chairs, and little tables everywhere. Ryan and Polly and Sam and Tara were standing in front of an oversized gunmetal gray casket. The lid was closed. I said a small prayer of thanks. As we moved closer to the family, I could see that the Seawrights were doing what they do best: comforting everyone else. They were so calm. I was getting really, really nervous. When I reached Ryan, I burst into tears. We talked about how long I had known John. Ryan said, "Even if you had only known John for one day, you would have known you had a true friend." Polly was composed and gracious. Tara remembered me from dinner in New York. Then I reached Sam. Living in New York obviously agrees with Sam: he gets more handsome and self-assured with each passing year. He told me that he had always felt like he could leave Athens because John was there, looking out for him and letting him know what was going on. Now, he and Tara would have to start coming down more and keeping in touch. I was afraid to even look at the casket up close. Could John's body really be in there?

We moved on, to make way for others to speak with the family. There were flowers everywhere. Most were huge wreaths, with a variety of flowers beautifully arranged, like the one from John Taylor in Charleston. Betty Alice Fowler and Heli (Montgomery) Willey brought a big bucket of daisies and nandina that they had bought, augmented with intensely violet-colored blossoms from BA's yard. There was a pound cake sitting on a desk in the foyer. I was sure that many of its brothers inhabited the counters of the Seawrights' kitchen. I went out on the front steps, where a number of people were gathered. Most of them looked vaguely familiar. Others, like David Gamble, Lori Shipp, Blair and Betsy Dorminey, and Ken Tapscott needed to be talked to. I went to Lori first, because I had heard that she was trying to gather up her courage to go inside.