Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

William Alexander Gowen (1634-1686)

My 8X great-grandfather

On September 3, 1650, my Scottish, 8x great-grandfather, William Alexander Gowen, was captured at the Battle of Dunbar by Cromwell’s army. He was only 16 years old.

The Battle of Dunbar was where Scotland squandered an incredible opportunity to defeat Cromwell and change the course of British history. It was Scotland's best and last realistic chance to chart its own political and religious destiny though the opportunity was wasted by a committee of Presbyterian ministers blinkered by religious fanaticism. The fiasco ended in an English-controlled death march of 5,100 Scottish prisoners of war. One of the most unsavory pages of British history.

William was one of about 9,000 Scottish soldiers captured, and one of the 5100 prisoners on the 100+ mile march from Dunbar, in Scotland, to Durham, in England in just over 8 days. The mortality on the march was very high. The Scots were beaten, starved, and when too sick to continue, left to die or killed outright. On the march, as they were coming to their first stop in Newcastle, many were dying by the dozens as uncontrolled dysentery and typhoid fever swept through the Scottish soldiers. When they arrived in Newcastle they were put into St. Nicholas Church, where more prisoners died among the pews. The following morning, about 500 of the prisoners could not continue the march and were left behind to die. Few prisoners made it out since most of the men who tried to escape were caught and shot.

Disease swept through the prisoners, killing off at least 1500 in the course of a few weeks. The “flux”, what we now call dysentery, was responsible for over 500 of those deaths.

The prisoners were put under the care of Sir Arthur Heselrigge, who wrote on October 31, 1650, that “1600 died altogether in 58 days”.

With very little for the English foot soldiers and cavalrymen to eat, there was virtually nothing for the prisoners to eat. Civilians along the way occasionally risked English vengeance and tossed them bread or whatever else they could spare, which wasn’t much after a summer of fighting in the area. The prisoners quenched their thirst, on the march, from puddles of rainwater and fetid ditches.

Late in the afternoon of September 11, 1650, about 3000 survivors staggered into Durham Cathedral. They were given no fuel and little food, but Sir Arthur Haselrigge wrote to Cromwell, telling him that the men had been given braziers and coal, and had been fed too. Haselrigge proudly told his fellow members of Parliament that his cathedral prisoners were provided with “pottage made with oatmeal, beef, and cabbage~ a full quart at a meal for every prisoner”. He also mentioned how his officers set up a hospital for the sick and wounded in the adjoining Bishop’s Castle, where patients were stuffed with “very good mutton broth, and sometimes veal broth and beef and mutton boiled together. I confidently say that there was never the like of such care for any such number of prisoners in England”.

It may have been what Haselrigge, in Newcastle, thought was happening, but his English guards in Durham were getting rich quick, by getting away with murder. Tons of supplies coming in from Newcastle and “60 towns and places” in the Durham area were being stolen by the cathedral guards. Some of the food was being sold to the prisoners for whatever money or personal jewelry they had managed to retain. Most of the prisoner's rations went at cut-rate prices to merchants and grocers in the area. It is believed that Haselrigge did his best for the prisoners, and had no real idea of what was actually going on. The harsh reality is that very little food ever found its way into Scottish stomachs. Many died of starvation, but most of the deaths were from the “flux”, or dysentery.

A very perplexed Haselrigge wrote, “some were killed by themselves, for they were exceedingly cruel one towards the other. If any man was perceived to have any money, it was two to one he was killed before morning and robbed. If any had good clothes that [a prisoner] wanted, he would strangle the other and put on his clothes. They were so unruly, sluttish, and nasty, that it is not to be believed. They acted like beasts rather than men”. No wonder, the prisoners were dying at an average rate of 30 a day in the cathedral. That rate probably hit close to 100 or more daily by the middle of October, as starvation and murder set in and the dysentery infection rate peaked. In actuality, they were trying to survive, but the English soldiers didn’t leave them much room for that; a truly horrendous situation.

The English Commandant also insisted, from Newcastle, that his prisoners were getting an ample supply of coal to warm them as winter was getting closer~ at least that's what the men in charge of the cathedral were telling him. “They had coals daily brought to them, as many as made about 100 fires both night and day and straw to lie on”. But it appears the coal like the food, was ending up everywhere except Durham Cathedral.

Simply to stay alive, the Scots burned every sliver of wood in the church~ the pews, the altar, anything that would keep them warm, regardless of religious significance.

By the end of October 1650, approximately 1600 Scots had died horrible deaths in Durham Cathedral. Only 1400 of the 5100 men who started the march from Scotland in September were still alive less than 2 months later when they were being transported away.

Far more Scots died as English prisoners than were killed at Dunbar.

To this day, there is no memorial of any kind to these unknown Scottish soldiers. They rest in anonymity, in what they would have regarded as foreign soil, far from their homes.

After three months of hardship ~ confinement, disease, bad food and no food, it was remarkable that our William managed to survive, and in many respects, thrive. For a 16-year-old boy, who could survive the march, the diseases and terrors at Durham Cathedral, the horrors of the ocean trip below decks in winter, and the rigors of lumbering in Maine, he thrived and became a man.

William Alexander Gowen was #38 on George S. Stewart's “Captured At Dunbar” list.

The prisoners were sold as indentured servants at about 30 pounds each ($4790.02 in current dollars). The average passage at that time was only 5 pounds each ($798.34 in current dollars). The captain of the ship “Unity”, that William came over on, made a “killing” on the amount of money he made transporting 150 prisoners to New England.

The Rev. Joseph Cotton referred to this indenture as “apprenticeship” for a period of 7 or 8 years, although some served for longer periods. When these indentured workers were set free, they were destitute, so the town of Kittery granted them parcels of land.

It’s been recorded that William was one of 15 ‘sold’ to the Great Works sawmill at South Berwick Maine. Dr. Emerson Baker, of Salem State University, who has done extensive research and an archeological dig, believes that one or some of the 15 also possibly worked for Humphrey Chadbourne, at his sawmill at Salmon Falls, which was just a short way along the river from Great Works. It would have been my 8X great-grandfather, William Gowen, working for my 7X great-grandfather Humphrey Chadbourne. (The Humphrey Chadbourne story will come later.)

After William's indenture, he settled at South Berwick and found work as a carpenter. But in 1659 he was convicted of “frequenting the taverns and being in a “quarrel” with fellow Scot, James Middleton”.

He first appeared in Kittery, Maine (now Eliot) in 1666.

In May 1667 it was recorded that Major Charles Frost, brother of one Elizabeth Frost (1640-1733), filed a complaint against William for “bastardy” with regard to his, and Elizabeth's son Nicholas. William and Elizabeth were married one week later, on May 14, 1667, at Kittery, York, Maine. Elizabeth brought a sizeable dowry into her marriage of 105 pounds 12 shillings and 6 pence, for a total of about $21,251.47 in current dollars. A big windfall for the boy from Scotland. Marrying Elizabeth put him into the more well-to-do strata of society.

Along with their son Nicholas, they had a total of 8 children. My family comes down through 3 of those children, Nicholas (1667-1741) John (1668-1732), and Margaret (1678-1751), our 7X great-grandfathers and 7X great-grandmother.

In June 1668 William was fined “for fighting and bloodshed on ye Lord’s day after ye afternoon meeting”. He was sentenced to pay a fine of 3 shillings 4 pence for breach of place and 5 shillings for breach of ye “Saboth”. Also fees of 2 shillings and 6 pence, in all 10 shillings 10 pence, $108.98 in current dollars. (NH court records)

1670, he was granted a house lot in Kittery

1674, he was a constable in Kittery

1676 he bought land on the Kennebec River, including Small Point.

1679- was in court for idling away time and drinking.

William Alexander Gowen died on April 02, 1686, Kittery Maine

Elizabeth Frost died in 1733, Kittery Maine

When William died the amount of his estate was over $53,000.00 in current dollars; a healthy amount for the times.

0 notes

Text

I’ve enjoyed learning about my people that came before me, you know, all the genealogy and DNA stuff. Doing my research makes me think of being a detective searching for clues. I love finding new and interesting (maybe just to me) stories of my ancestor's lives, through the bits and pieces of clues I’ve found. I posted on Facebook recently about a woman who disguised herself as a man and fought in the American Revolution as a patriot. Her name was Deborah Samson, and she was my 4th cousin 6X removed. I’m writing stories about different ancestors, to be able to combine them into a book for my family. If people are interested, I’ll be writing and posting about a different ancestor at least one a week, that’s my goal, and I’m sticking to it! My next story is about Rebecca Towne Nurse, one of the victims of the Salem Witch Trials, she was my 9X great-grandmother. Something I found out was my parents were 10th cousins, both being related to Rebecca’s father William Towne. My mother came down through Rebecca, my father came down through her brother Joseph.

Rebecca Towne Nurse

(1621-1692)

9X great-grandmother

Rebecca Towne was born on February 13th, 1621, in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, England. She was the eldest of eight children of William and Joanna (Blessing) Towne. William and Joanna arrived in America c. 1635, with six of their children, the last two were born in Salem Massachusetts.

In 1644 Rebecca married Francis Nurse (1617-1695) who was born in England and emigrated c. 1640. The first mention of him in Salem, lightly crossed out in court records, (probably by a sensitive descendant) is the presentment on March 31, 1640, of “Francis Nurse a youth for stealing of victuals (food) and for suspicion of breaking into a house”. Francis was only 19 at the time and apparently was hungry, but his integrity and character improved over time, and thought of later in life, as an upstanding member of the community.

Rebecca and Francis raised their eight children on a farm in Salem Village, now known as Danvers Mass., near Salem. Their children were John Nurse b. (1645-1719), Rebecca (1647-1699), Samuel (1649-bef.1720), Elizabeth (1656-1733), Mary (1657-1749), Francis (1660-1716), Sarah (c.1651-1754), Benjamin (1666-1747) . Our family comes down through John.

By trade, Francis Nurse was a tray maker, which included making many other wooden household articles, as well as farming, because the demand for trays could hardly produce an adequate living.

When the colony and the towns of Salem and Topsfield made early grants of heavily forested land, not much attention was paid to accurate boundaries. The result was that as they were cleared and cultivated, the obscurely defined grants were found, in some cases, to overlap. In 1678, Nurse had hardly been given possession of the 300-acre parcel of land, that he had made a deal to lease to own when the conflict of the boundaries descended on him. (This farm still exists and is preserved as the Rebecca Nurse homestead).

Many books have been written about the Salem Witch Trials, so I’m not going to go into too much detail about that. Except to say, I believe the problems for Rebecca started years before the trials. There was the issue of the land grants and confusion about the boundaries, which produced a number of enemies. Also, the issue of Rebecca’s mother Joanna Blessing Towne, who twenty years earlier had been accused of witchcraft. (It was believed at that time that witchcraft was spread among family members, especially among the maternal line). The cause of the witchcraft accusation, some believe, was because Joanna testified in court on behalf of Rev. Thomas Gilbert, who was the first ordained minister of Topsfield MA. According to resources “...he was tried for intemperance and as there was no doubt of his guilt, his connection with the church was severed”. “The charge was not on account of his use of wine, but because of his coming intoxicated to the Lord’s table”. Joanna had testified saying she had witnessed the incident in question and stating the Reverend had not had too much to drink. Her defense of Gilbert contradicted the testimony of the very powerful Capt. John Gould (1635-1710 my 10th great-granduncle). In addition, it was said Joanna had been heard speaking ill of her daughter-in-law’s mother, Phebe Gould Perkins (1620-1686 my 10th great-grandmother), the oldest daughter of Zaccheus and Phoebe Deacon Gould. Zaccheus’ sister Priscilla was the wife of Putnam patriarch John Putnam of Salem Village. Making enemies of both the Goulds and Putnams was not wise. It’s very possible that Joanne became a target for going against them.

The boundary dispute between Topsfield, Salem Village and Salem Town, went on for many years.

The third generation of the Putnam family was Thomas Putnam Jr. his wife Anne Sr. along with their daughter Anne Jr. who were the principal accusers during the witch trials. Thomas was responsible for accusing 43 people, his daughter was responsible for 62, Rebecca Nurse being one of them.

With the boundary dispute principles between Salem Village, where the Putnam family led the faction, and Salem Town, where the Porter family led the faction, the Nurse and Town families followed the Porters, who identified with the mercantile town. Those same lines of dispute explain the pattern of witchcraft accusations. The same villagers who stood with the Putnam’s, show up as complaints on witchcraft indictments during the trials. Similarly, many of the accused in Salem belonged to the Porter faction.

People have been giving reasons for the witchcraft trials for centuries, from witchcraft, and ergot fungus poisoning on the barley to greed and hatred. I believe it was greed for land and revenge.

In 1692, Rebecca Nurse was 71 years old and had raised 8 children. She was a fervent churchgoer and was well known for her piety; but also, being only human, she could lose her temper on occasion. A newspaper of the day referred to her as “saintlike”, and a perfect example of good Puritan behavior. Rebecca would be accused, tried, and convicted of witchcraft and put to death without the legal protections Americans would later get.

Rebecca was accused on March 19th. A warrant issued on March 23rd for Nurse’s arrest included complaints from Anne Putnam’s Sr. and Jr., Abigail Williams, and others. Rebecca was arrested and examined the next day. (During her examination on March 24th, she was quoted as saying: “I can say before my Eternal Father I am innocent and God will clear my innocency… The Lord knows I have not hurt them. I am an innocent”). She was accused by townspeople, Mary Walcott, Mercy Lewis, and Elizabeth Hubbard, as well as Anne Putnam Sr. who testified that the ghosts of Benjamin Houlton, Rebecca Houlton, John Fuller, her sister Bayley, and her three children, came to her at various times in their winding sheets and cried for justice of being murdered by Rebecca Nurse. Anne Putnam Sr. “cried out” during the proceedings to accuse Nurse of trying to get her to “tempt God and dye” Rebecca stoutly denied the charges, but was indicted for witchcraft. She remained in jail.

On April 3, Nurse’s younger sister Sarah Towne Cloyce came to her sister Rebecca’s defense. Sarah was accused and arrested on April 8th.

On April 21, another Towne sister, Mary Towne Estey, was arrested after defending her sisters.

On May 25th, judges John Hathorne and Jonathan Corwin ordered the jail in Boston to take custody of Rebecca, Martha Corey, Dorcas Good (Sarah Good’s daughter age 4) Sarah Cloyce, John and Elizabeth Parker, for acts of witchcraft committed against Abigail Williams, Elizabeth Hubbard, Anne Putnam Jr, and others. A deposition written by Thomas Putnam, signed on May 31, detailed accusations of the torment of his wife, Ann Putnam Sr. by Nurse and Corey’s “specters” or spirits.

On June 2nd four indictments were returned against her for afflicting persons. On June 3, a grand jury indicted Nurse, and John Willard for witchcraft. A petition from 39 neighbors was presented on Rebecca’s behalf and several neighbors and relatives testified for her. On June 28, 29 and 30th, witnesses testified for and against Rebecca. Several witnesses, at that time, testified they were afflicted by her, that her apparition pinched and choked them, and was threatened by death. Rebecca’s body was searched for a “witches mark” of which one was found. On the same day, Rebecca was examined, Bridget Bishop, John Proctor, Alice Parker, Susannah Martin, and Sarah Good were also forced to undergo physical examinations by a doctor, with some women present. Nine women signed the document attesting to their exams. A second exam later that day stated that several of the observed physical abnormalities had changed; they attested that on Nurse the “witch mark” “appears only as a dry skin without sense”. Again nine women signed the document.

The trial was a sham and a virtual mockery of the judicial system. The complaint against Rebecca was signed by Edward and Jonathan Putnam, family members of Thomas Putnam. At her trial, testimonials regarding her Christian behavior, care and education of her children, brought a verdict of not-guilty. But a guilty verdict for Sarah Good, Elizabeth How, Susannah Martin and Sarah Wildes. William Stoughton, (a colonial magistrate and administrator in the Province of Massachusetts Bay) then politely asked the jury to again retire and reconsider their verdict. Stoughton was not satisfied with the verdict. He wondered what Nurse had meant when, after Deliverance Hobbs was brought into the courtroom to testify against her, Rebecca had said, “But she is one of us”. Nurse was brought back into the courtroom and asked: what had she meant? Rebecca did not answer, she was old, hard of hearing and overwhelmed. She stood silently, her silence was interpreted as an admission of guilt. The verdict was reversed and she was found guilty. Later, she explained in a statement, that she said what she said because Deliverance Hobbs had been in jail with her. Grave charges have been made against the chief of justice in this case, as he practically forced the jury to reverse their not guilty verdict.

Rebecca was condemned to hang!

The Massachusetts governor, William Phips issued a reprieve which was met with much protest, was soon rescinded. Rebecca filed a petition protesting the verdict, pointing out she was “hard of hearing and full of grief”, and had been unable to hear the last question asked of her.

On July 3rd, Rebecca was taken into the Salem Church and excommunicated in front of the entire congregation.

On July 12th William Stoughton signed death warrants for Rebecca Nurse, Susannah Martin, Sarah Good, Elizabeth How, and Sarah Wilde. All five were hanged on July 19th on Proctors Ledge.

As was the custom at the time, after Rebecca was hanged, her body, along with the others, was buried in a shallow grave near the execution spot. They were considered unfit for a Christian burial in a churchyard. According to oral tradition, Nurse’s family secretly returned after dark and dug up her body, to be properly buried later that night, somewhere on their homestead. The exact location was kept secret by the family because they were afraid her body could be dug up and taken away, by those who prosecuted her. In 1885, some descendants of hers erected a tall granite monument at the Rebecca Nurse Homestead cemetery. The inscription on the monument reads:

Rebecca Nurse, Yarmouth, England, 1621. Salem Mass. 1692

O Christian Martyr who for truth could die

When all about thee owned the hideous lie!

The world redeemed from superstitions sway

Is breathing freer for thy sake today.

(From the poem “Christian Martyr” by John Greenleaf Whittier)

In 1706, one of her accusers, Anne Putnam Jr., gave a public church confession upon entering the Salem Village Congregation. She expressed great remorse for her role against Rebecca and her two sisters, Mary Estey and Sarah Cloyce, in particular. “I desire to be humbled before God for that sad and humbling providence that befell my father’s family in the year about ‘92; that I being in my childhood, should by such a providence of God, be made an instrument for the accusing of several persons of a grievous crime, whereby their lives were taken from them, whom now I have just grounds and good reason to believe they were innocent persons; and that it was a great delusion of Satan that deceived me in that sad time…” The Nurse family accepted Anne’s apology and were reconciled with her.

In 1711, Rebecca’s children petitioned the government for a reversal of attainder, which they received, and were granted compensation for Rebecca’s wrongful death.

In 1712, the Salem Town church reversed the verdict of excommunication it had passed on her, “that it be no longer a reproach to her memory or an occasion of grief to her children”.

The Nurse family lived in the homestead for many years. Eventually the house and land were sold to Phineas Putnam, a cousin of Rebecca’s great-great-grandson, Benjamin, in 1784. The Putnam family remained at the Nurse’s homestead until 1905. By 1909 the farm was saved by volunteers and turned into the Rebecca Nurse Homestead, a historic house.

0 notes

Photo

Silk fukusa (gift cover) embroidered with a flight of cranes, Japan (c. 1800-50, Edo period) [OS] [1000x1237]

Source: http://www.vam.ac.uk/__data/assets/image/0010/184672/2006ap6978_flight_of_cranes_fukusa.jpg

106 notes

·

View notes

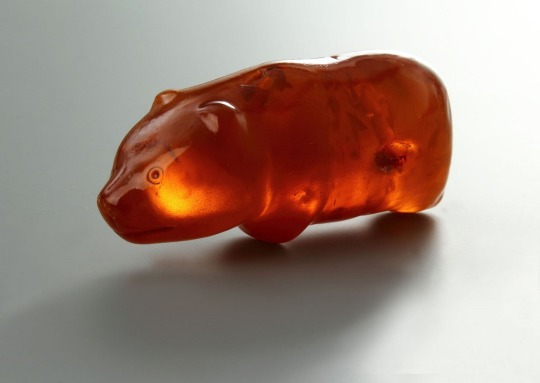

Photo

Amber bear amulet of neolithic hunter. c. 3500 years old

224K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Flashy Ammolite looking like a trippy stained glass window via @rocksforthespirit //////

www.instagram.com/rocksforthespirit

www.mineraliety.com

620 notes

·

View notes

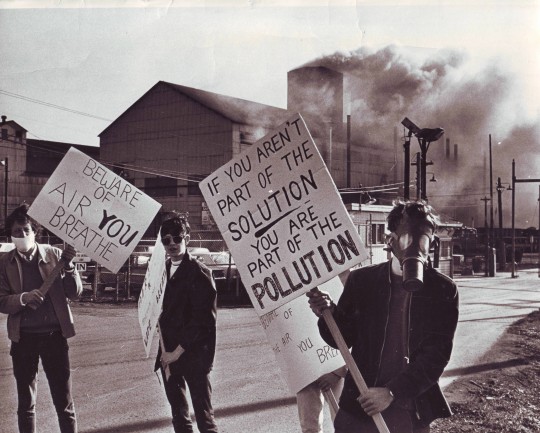

Photo

April 22nd 1970: First Earth Day

On this day in 1970, the first Earth Day was celebrated, marking what many consider the beginning of the modern environmental movement. The environmental movement capitalised on increased activist fervour which gripped the United States during the Vietnam War. Attention had increasingly been turned to the problems plaguing the natural landscape, especially after Rachel Carson’s book Silent Spring in 1962. The idea for Earth Day came from Senator Gaylord Nelson (D - WI) after an oil spill in Santa Barbara, CA. Nelson teamed with activist Denis Hayes, who led the national promotion of the day. Earth Day proved a popular idea, garnering support from Republicans and Democrats and people from all walks of life; it also encouraged the Nixon administration to create the Environmental Protection Agency and led Congress to pass several environmental measures. In 1990, Earth Day was again commemorated, and this time on an international scale, reaching 141 countries and involving 200 million people. The celebration only grew from there, and continues as an annual event around the world. However, Earth Day now faces a formidable challenge from climate change deniers and powerful lobbying groups.

2K notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Knap of Howar, a neolithic farmstead in the Orkney Islands of Scotland, that was occupied from 3700 BC to 2800 BCE. It is perhaps the oldest preserved stone house in northern Europe. (I say “perhaps” because archaeologists like to argue with each other, especially when titles like “oldest” get involved.)

755 notes

·

View notes