Text

The Mid-Thirty

On the train to Mt. Fuji. Photo by Georgie Todman.

And so, here we are again: Happy Birthday to me! Who would have thought that 35 would come around so quickly? If I’m honest, this circling of the sun has felt a bit like a test, and I am grateful to have apparently passed it, and for the hard reset of a new year: the sense of something over, with a fresh start to go with it. There were wonderful parts to it, but, for me at least, it was a hard year. And I made it.

It began with one of the biggest challenges I have faced in a decade or more: performing the role of Katurian in the Launceston Players’ production of Martin McDonagh’s The Pillowman, directed by my dear friend Mitchell Langley. This is a work that I have loved since I first studied and performed a monologue from it in Year 12: a wild, terrifying story that is as tragic as it is funny, exploring the deep darkness of humanity, questions of censorship, art, and the role of the artist. It was an enormous undertaking and extraordinarily ambitious for my first foray back into theatre after more than a decade (as my nightmares throughout the season occasionally attested), but I am nevertheless so grateful for the experience I had working with the incredible team on the project, all of whom supported and guided me every step of the way. As far as leaps outside my comfort zone go, it was a big one, but I learnt so much and I loved every moment of it. Last week, I was delighted to hear that my performance was nominated for a Tasmanian Theatre Award for Best Male Leading Performance Community Theatre, which will be announced at the end of February, so as out of my depth as I often felt, I'm hoping that's a sign that I might have done something right! If taking on The Pillowman should have been the big challenge of 2024, it was sadly outstripped by a surprise contender. Sometime during the beginning of the school year, I contracted covid for the first time (a miraculous near-four-year effort, considering that I have been working in a school of 1300 students for all of that time). For two weeks, I crawled out of bed in order to fire off some lesson plans to my substitute teachers in the morning, then crawled back, exhausted, unable to concentrate on even the television, let alone a videogame or a book. Eventually, after returning to school, I would finish a day’s teaching and lock the door of the classroom as the students exited, then fall to the floor exhausted and drenched in sweat. Any exercise at all sent me into decline again. I was very lucky that my school helped me develop a plan to get back on track, and I knew that my only option was to surrender. I made a new phone background based on a famous line from Trent Dalton’s Boy Swallows Universe: the repeated phrase, “It gets good.” And it did. Finally, in October, eight months after my initial infection, I had my first week without a “bad day.” By November, I still hadn’t had any, and I'm still going strong. People ask if I’m 100% now, and I have to admit that I’m not, but I also don’t think that 90% is too bad. I’m grateful, at the moment, to feel like myself again.

This year also saw co-president Georgie Todman and I spearhead our first joint iteration of the Tamar Valley Writers Festival. We were very excited by the time October rolled around, and our wonderful team was working round the clock to bring everything together, but while it was exhausting (and I am so grateful that my health was in a good place by this point), the honest truth is that, as a crew of committee, employees and volunteers, we had a ball. Our guests were exceptional, and we regularly had to pinch ourselves. Did I really interview Markus Zusak in a room of hundreds of people? What is this life?

Through all of this, of course, was teaching—which remained my anchor to normality, routine, and the life-giving energy of working with my students, but which also left me wondering about what the future might look like. This will come as a shock to many, but at the end of the year I made a big decision: after a remarkable seven years at Launceston College, I packed up my office, cleared out the filing cabinet, and I am heading to Cressy District High School starting next week. I’m nervous about making the adjustment to a new school for the first time in my teaching career to become a Grade 7 teacher, but it’s an excited kind of nervous, and on a visit there late last year to meet the staff, chickens, sheep, highland cows and resident lizard—book-ended by the first of many daily drives under the Western Tiers—I felt an enormous sense of potential: for what I hope will be the contribution that I can take to Cressy from my time at Launceston College, and for what I hope I will learn from Cressy to take with me to whatever and wherever comes next. Looking back on the last seven years, I could not be more proud of the work that I have done, and the way that I have thrown myself into this profession, and I already miss the connections with students, families and staff that I got to share at LC. That school changed my life: once, as a learner myself, who fell into the deepest romance with the written word inside its halls, and then again, when I found my greatest joy sharing that enthusiasm with the next generation. I often say that I hope one day to have enough success in my writing to balance the scales of my time slightly: to be a writer and a teacher in something more like equal measure. Until then, I can’t help but acknowledge that if I were to be visited in the dark of the night and told that it was one or the other? I’d be a teacher. I love being connected to people, and, whatever else might be going on in my life, I wake up every day with something important to do. Following the recent death of John Marsden, who I admired so much as both an educator and writer (as well as the life he created by the balance of the two), I have been revisiting his work and history and was amazed to see him asked in an episode of 60 Minutes whether he felt that being a best-selling author or educator was more significant. Surprisingly, he didn’t hesitate to declare that his work in education was the most meaningful work that he had ever done. In that moment, I felt a sudden sense of calm about the path I continue to walk.

There are so many other small and large moments that could rate not only a mention here, but a whole post of their own: travelling (and my continuing obsession with Japan), adventures in nature, theatre performances of loved ones, mentorship, birthdays, weddings and a public reading by Mudlark Theatre Company of the first draft of my own play: The Second Death of Alice Crane. It’s been a hard twelve months, but also one that I will look back on with pride and a real sense of achievement. Its toughness has made me tougher, and also—I hope—gentler. This year, I have relied on the people around me who care to keep my spirits up, and to remind me of what is important; to help, to wait, and to have my back. Some years cast long shadows, but, if I’m honest, I struggle to think of even the worst of them as “bad,” because I get to share all of them with the people that I love. I miss those I have lost, of course, but I have never really felt nostalgic for the past… why would I want to be anywhere but here, with these wonderful people, making these memories?

On my birthday, this is my wish: I hope that—whatever 2024 might have brought you—2025 brings you wonder. There is so much pain in the world, but there is also so much joy, and we owe it to ourselves, whenever possible, to walk a careful line: to fight against injustice, to know that small acts create ripples, and to hold each simple pleasure as a sacred thing. If you need a reset, remember that each year is a marker and a waypoint of possibility, but so is the month, so is the day, and so is the hour. I know now, from the supposed-middle of my thirties, that all of it is arbitrary. Every minute we can start again.

Here I am, at thirty-five, grateful. Thank you for being my friends. I hope for you a year of wonderful beginnings.

0 notes

Text

Why I’m Performing in The Pillowman in Five Days

Time moves quickly. I think it was only a moment ago that we had months ahead of us to rehearse, and yet that expanse of time has receded as swiftly as waves on the shore. Somehow, I have very quickly reached a point where I have only five days before I will be acting on-stage at Launceston’s Earl Arts Centre, for the first time in fifteen years. I am playing the part of Katurian the writer (originated by David Tennant in the 2003 premiere of the play, and most recently in 2023 by Lily Allen) in Martin McDonagh’s The Pillowman, directed by Mitchell Langley for the Launceston Players, which also stars Travis Hennessy as Tupolski, Lauchy Hansen as Ariel, Jesse Apted as Michal, and Renee Bakker, Michael Mason and Eva Cetti in various roles. As the play begins, my character is dragged in for questioning by the police. He writes powerful—but very disturbing—short stories, and it seems that someone is bringing those short stories to life.

Wouldn’t it make sense that he has something to do with it?

It all sounds pretty grim (and in many ways it is), but if you are at all familiar with McDonagh’s writing then you’ll know that he can be relied upon to strike an electrifying balance between horror and comedy. His works include The Lieutenant of Inishmore (2001), A Behanding in Spokane (2010) and Hangmen (2015) for the stage, while more recently he has made his name as the Academy Award-winning writer and director of In Bruges (2008), Seven Psychopaths (2012), Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri (2017) and The Banshees of Inisherin (2022). While The Pillowman is undoubtedly one of the darkest plays I’ve ever come across, it is also one of the funniest.

A year ago, I probably would have considered it unlikely that I would find myself here. In fact, I find it pretty unlikely even now, just days away from opening night. So why did I want to be part of The Pillowman? Aside from the obvious strengths of the team behind the project (who have taught me so much, whilst also giving me the delightful and terrifying challenge of trying to prove my right to share the same stage as them), this is a play that is very close to my heart. In 2008, in my Year 12 Theatre class, my teacher Nicole assigned me Tupolski’s famous railroad tracks monologue as my assessment piece, which I also later performed at a college academic awards night. Ambitious creature that I was, I wouldn’t dare perform something like that without first having its context in the whole work. She lent me a copy of the play—the first time I had seen one of those strange slim paperbacks with no picture on the cover (this one was orange, as is the copy I am learning my lines from now). I went home and read it. I was laughing, I was shocked, and I was moved, all in equal measure. Oh, of course there’s something special about a work of literature that finds you on the cusp of a new phase of life, and most of my favourite books are books that I found (or that found me) that year. But aside from Shakespeare’s Hamlet (which I also discovered just before finishing school, and found myself falling into, and have since found it very hard to clamber back out of), The Pillowman swiftly became my favourite play, and Martin McDonagh my favourite living playwright. There have been a number of times on this blog where I have talked about the challenge of balance, how we prioritise and choose what to spend our precious limited time and our creative resources on. For me, the only thing worse than having the burden of auditioning for The Pillowman, being offered a part in it, and rehearsing and performing it, was the horrifying thought that someone else might get to do it in my place.

And so, here I am.

In my teaching of English, one of the most important concepts that I discuss with students is that of an “invited reading.” What I mean by this is not merely what the author (or even a character) says, but what the audience is supposed to take away as its meaning. Bad things happen in literature, but the existence of evil as a narrative element is not necessarily an endorsement of it, even if it might be tempting and easy to think so. In our inattentive world of click-bait headlines, out-of-context soundbites and addiction to outrage, it can be very easy to mistake a single puzzle piece for the whole picture, and while it happens constantly, it happens at our own peril. This is the very essence of what The Pillowman is asking us to consider: what stories are we allowed to tell? How do we shape the audience’s understanding of what we are trying to say? Can we shape the audience’s understanding of what we are trying to say? Should we be expected to? In the end, is it even fair to say that stories mean anything at all?

In a prescient update relating to the show’s themes, on World Poetry Day last month, PEN International released “War, Censorship, and Persecution,” an international case list for 2023/2024, highlighting the latest challenges for writers in global conflicts and emphasising the need to safeguard freedom of expression, especially in war-torn regions. The report documents 122 cases of writers facing harassment, arrest, violence and death worldwide. This is why the tale of Katurian still matters: because we do not yet live in a world where you can be sure that a story will not cost you your life.

A few days out from opening night, I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that I was a little scared. There is never a moment where I am not on-stage in the play. Playing Katurian as a return to performance is the theatrical equivalent of “having another go at swimming” by throwing myself into the churning waters of the Atlantic.

But that’s the point, isn’t it? I’m scared. Oh yes, I’m scared. But I have a story that needs telling.

The Launceston Players Production of The Pillowman, directed by Mitchell Langley, is on-stage at the Earl Arts Centre Wednesday 24th April at 7:30pm, Thursday 25th April at 4:30pm, Friday 26th April at 7:30pm, and Saturday 27th April at 2:00pm and 7:30pm. Tickets are still available at Theatre North.

0 notes

Text

Door 34

Photo by Georgie Todman.

A few months ago, I got a gnawing feeling. It felt like the slow rising of a wave of overwhelm, and that the little boat I called my life was floating somewhere in its path.

I was behind on edits working with my wonderful mentor, Mark Macleod, on my children’s novel. I was attending a series of workshops developing a brand new project for a local theatre company. I had just returned from an international holiday, and I had a job application to complete and a stack of creative writing folios to mark, not to mention all of the emails I had to answer. My house was in disarray (never a good sign), and I was recovering from a knee injury that was making running difficult. I was a busy boy, and it felt like everything that had once been a blessing had suddenly become just one more thing to constantly be worrying about.

I sat down on the couch with my head in my hands. What was I going to do?

After a moment (and a big sleep), I thought about everything a little more. What was I really doing? I was writing a children’s book, and in a month’s time I would have the opportunity to pitch its concept to some of Australia’s best publishers. I was creating an original play in an environment where I had an enormous amount of creative support, and it was growing every day. I had been to Japan, where I had driven a go-kart around the streets of Tokyo, undertaken a traditional tea ceremony, and visited the world of Harry Potter at the Universal Studios theme park. I had almost cracked a twenty-minute five km personal best in my running, and I was working at my favourite school, teaching my favourite subject and had a new leadership position. I was co-President of one of Tasmania’s largest literary festivals.

It was a lot to sift through. But, I reflected, Lyndon at 24 would have killed for the problems that I had now. For all of my challenges, I was living the dream of a younger version of me. I am living the dream of a younger version of me, even now.

Much has stayed the same for me in 2023. I wake up in my little house, largely following the same routine in which the clock might be set by coffees in the morning, green teas in the afternoon, and a cup of earl grey in the evening. Some things have changed, though. For the first time in more than a decade, I will be acting in April, in the Launceston Players’ 2024 Production of Martin McDonagh’s The Pillowman, a darkly funny comedy about a writer living in a totalitarian state being interrogated about the grisly content of his stories. Georgie and I, as co-presidents of the Tamar Valley Writers Festival, will be heading up our first fully-fledged event this year in October, bringing local and national storytellers to our hometown. After six years teaching English 3, this year I will be taking my first Philosophy class, and will spend at least some of my time unpacking the big concepts of the good life, ethics, and the mind/body problem.

I have been so very spoilt on my arrival at thirty-four. There were messages that my phone buzzed with all day that spoke of me in the kind of way that seemed perhaps to indicate a person I wish I was, rather than the way that I am, but which nevertheless made me feel that I might be doing something right. There was cake, and decorations, and presents that were as thoughtful as they were generous. There were enthusiastic happy birthday declarations at school, a family member who cancelled their plans that night to be able to spend more time with me, and food… food… so much food.

I live the kind of life now where I have almost an entire year laid out before me at every turn. The school calendar ticks forward from day one to exams with a frighteningly predictable progression that always gradually increases in speed and intensity. Trips, activities, performances and adventures start filling in the gaps long before the diary has officially turned from one year to the next. It is a gift, certainly, on some days, to be busy. There isn’t time to worry about the sorts of things that used to turn over in my mind for hours: the things said and unsaid, heard and not heard, the mistakes made and the undeserved successes. There is only time to hold on tight.

Most days, when I wake up, I feel lucky. I used to think of each new day, and each new year, as a blank page, but perhaps it would be more accurate to say that it is a door… not necessarily something that I get to write for myself, but something that waits for me, and that I only need enter to discover. There are times when it all feels really, really hard. Of course there are. But through all of the challenges I’ve faced, I haven’t yet had a year where I regretted where I've found myself. I have learnt and grown so much. I think Lyndon of ten years ago, and twenty years ago, would be proud of me. I think he’d be excited that one day he would get to be me, and open Door 34 for himself.

If you’re reading this, the chances are that somewhere behind that door you are waiting. Today, as I step through and turn the lights on to face the surprises of the year ahead, I feel so grateful to be here, and so grateful that you are too.

Whatever happens, this place is home now. And as the way back closes behind me, knowing that you are in here somewhere beside me, I am excited to see, and embrace, whatever lies ahead.

0 notes

Text

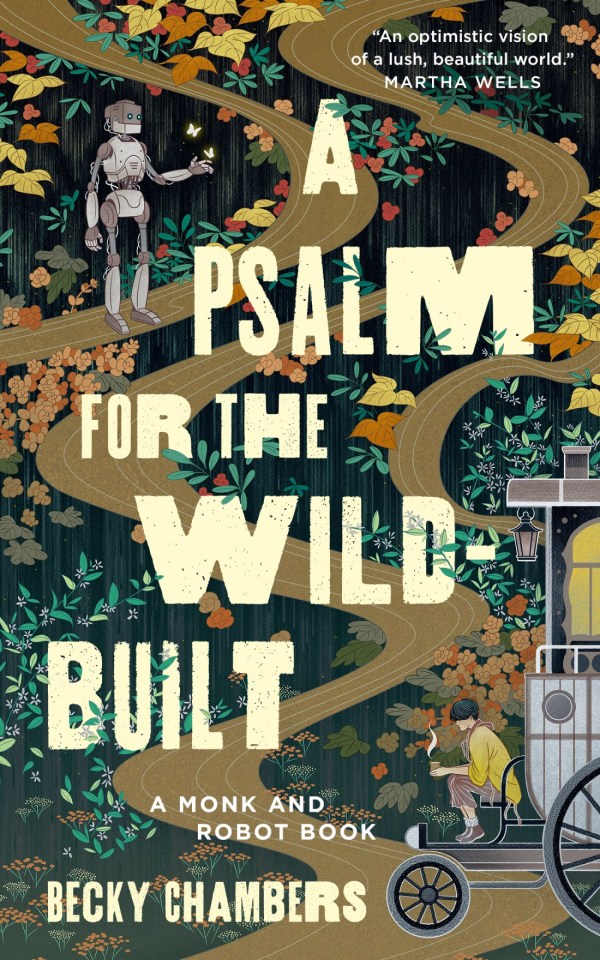

Tea and Coffee on a Winter’s Night: Psalm for the Wild Built, Legends and Lattes and the Welcome Rise of Cosy Fiction

Narrative structures in fiction have traditionally been fairly straightforward: give your audience stakes, the higher the better. If the entire world (or even universe) isn’t in peril, you’re probably not trying hard enough.

That said, as we reach the winter months here in Australia, like a lot of people I have begun to wonder if there isn’t demand for worlds in which the intensity level is set a little lower. During the lockdowns of Covid I sought solace from my fears in the world of the Nintendo videogame Animal Crossing, in which players are thrust into a new life on an idyllic tropical island, making friends with the creatures that live there and gradually improving the infrastructure of the town around them. Those who ask how to “win” the game have to be content with a non-committal shrug: Animal Crossing offers things to do and achieve, certainly, but the concept of ultimate victory is at odds with its essential nature. It is a safe place—all of the pressure of outcome washing away on a gentle tide. Similarly, for years the concept of “escapism” in literature has been a term of derision: a label that implies that both reader and writer are sharing a delusion in order to hide from their own realities. It is intriguing, then, that the genres of science fiction and fantasy—most commonly attacked with this charge—have embraced a recent turn towards an intensified version of this feeling. In “cosy” fiction, the danger is dramatically lowered, the tone is introspective and internally transformative, rather than externally so, and there is a focus on comfort: heart, hearth, armchair and hot beverage.

Cosy novels are cottagecore. They are the kinds of books you might read upon waking from a nightmare, the literary equivalent of a hot drink by the fire on a cold night.

I would love to introduce two of my favourites to you.

A Cup of Tea:

Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers

Becky Chambers’ glorious science fiction story (winner of the Hugo Award for Best novella) is the story of Dex, a non-binary tea monk who travels from town to town, composing bespoke blends and listening to the problems of the citizens that live in the places they visit. Dex always feels that something is missing, and one day they decide to brave the forbidden wilderness surrounding the urban areas. The wild is home to the world’s robots, who generations ago gained sentience and requested release from human society. One of them, Mosscap, finds and greets Dex. Together they continue their exploration and shared mission of helping soothe the ills of the troubled while finding purpose in their own lives.

Chamber’s book can be read in only a couple of hours, but its effect is longer-lasting. It is a tale that reminds us that acts of kindness may seem small, but their impact has echoes. Tea is the perfect symbol and metaphor for Psalm for the Wild-Built, a novella that is by turns soothing, meditative, and which never fails to warm some small forgotten corner of the human soul.

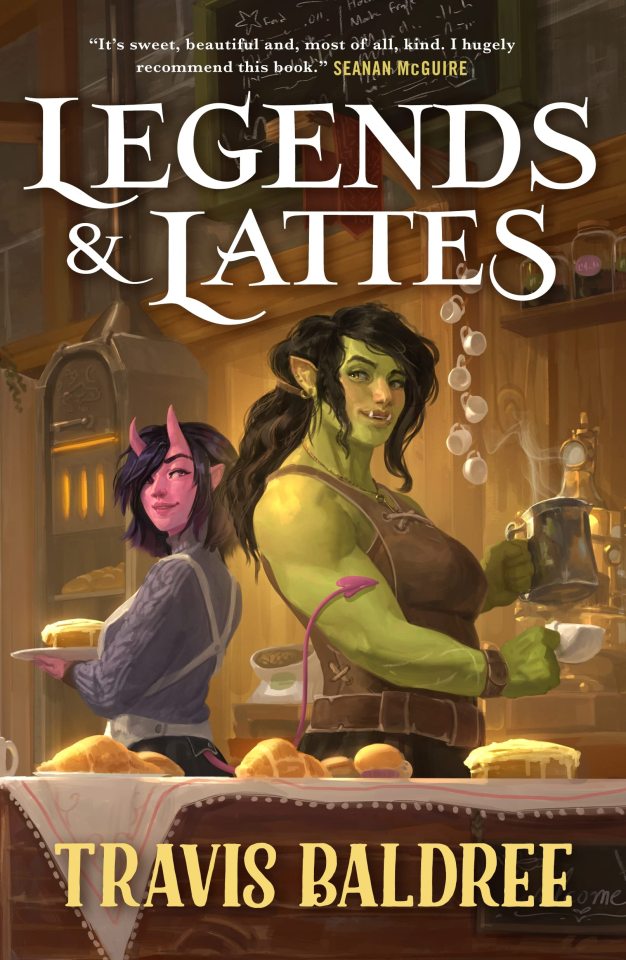

A Cup of Coffee: Legends and Lattes by Travis Baldree

Travis Baldree’s offering to the genre of cosy fiction takes readers to a very different landscape: the fantasy city of Thune. Here we meet Viv, an orc swordswoman and mercenary who has become weary of a life of violence and is captivated by an obsessive new vision: the possibility of starting a coffee shop. Her first hurdle, of course, is that no-one even knows what coffee is, but that is the least of her problems… her old life insists on trying to find a way to squeeze back in and drag her back to battle.

Like coffee, Legends and Lattes is similarly thawing but with a little more intensity of energy and a slightly sharper edge. Baldree creates a sense of community that is perhaps the book’s greatest asset, and both Viv and the reader form deep and enthusiastic connections with the novel’s diverse cast of characters: the hob Cal, the succubus Tandri, Thimble the baker, Pendry the bard and Amity the dire-cat. Watching Viv’s coffee-house gradually develop its menu, popularity and personality is a joy to behold. Quite simply, it allows for the reader to inhabit the part of living in a fantasy world that is lost to so many distant quests for forgotten treasures: community. If in most fantasy novels the reader finds a band of companion warriors, in Legends & Lattes they find friends: the kind that will sit with you quietly by the fire in an armchair, talking about nothing, with a freshly-baked cinnamon scroll to share between you. It is a story about friendship, love, and also about the fact that often in life it is the simplest of dreams that bring us the most satisfaction.

I love cosy fiction. As I explore the genre more, cosy books remind me, fundamentally, that it is okay for a story to just make us happy. We do not owe it to ourselves or anyone else that our literature is always an instrument and metaphor for struggle, personal improvement or academic deconstruction. What books can do—just as importantly—is give us a haven of respite from a chaotic world. A book can alleviate a small moment of human suffering. A book can heal a wound that you can’t see.

Many of us go to a cup of tea or coffee for a brief retreat and a touch of warmth in our bones.

If that’s the direction that fiction is heading in, pour me another.

#cozy fiction#cosy fiction#review#lit#psalm for the wild built#legends and lattes#becky chambers#travis baldree#original

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Goodbye Ellie

I can’t believe that I am writing this. It is too soon.

Shockingly and suddenly, four-and-a-half years into caring for her, my dear friend Robyn discovered recently that Ellie the greyhound had become very sick. Sadly, the vet confirmed that she was not going to get better.

Ellie, I am very sorry to say, is gone.

Ellie was a special creature. Like a lot of greyhounds, she had at least fifty percent more nose and leg than should have been reasonably allowed by law, and she had a way of looking into your eyes that sometimes made you think she knew absolutely all of the secrets of the universe, and sometimes made you think she knew almost nothing at all. When we filled the main hall at Launceston College with hundreds of people to launch the book we had created about her and she stood on stage looking out at the crowd, I always wondered… did she know that it was all for her? It seemed to me like she had just dropped down to Earth from another planet, and she was trying to work out what it meant to live here. Sometimes, out of the corner of my eye, I half-expected to catch her sitting up in an armchair and covertly flicking through the pages of a book called How to Dog.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, a couple of weekend ago, as the early mists rose over the high suburbs around Launceston, I was lucky enough to take Ellie for one last walk with the two of us together. It was certainly memorable. It was a Sunday morning, and from where Ellie and I wandered we could see the city and the river in the distance: a whole world below us to explore. As I returned back to the house and tried to drink my cup of tea, Ellie persisted in squeezing her head under the palm of my hand.

I went home with my jeans covered in slobber and tea splashes. I went home happy.

One thing that never quite came through in our picture book was what Ellie taught me about running. Reading Becoming Ellie, you might have thought that part of the story’s message is that Ellie will never run again. But Ellie was the master of what dog-people call “the zoomies.” Whenever the mood took her, the screen door would swing open and down the concrete ramp she would fly, onto the grass and around the backyard, running in circles and spinning at the same time, impossibly making the square of grass seem endless. She would freeze, launch, freeze again, and then bound this way and that, chasing some invisible wonder in a dance that was all her own.

Ellie ran again, she just ran differently. She ran chaotically. She ran without purpose. She discovered the simple truth that so many of us who turn our passions into vocation or competition need to learn: winning is one thing, but the best part of life is simply finding joy in the act itself.

Dogs like Ellie remind us of who we should be. To them, every opportunity to explore the world is a miracle, and every interaction with others is the best thing that has ever happened. Dogs like Ellie show the world that all of those carefully-curated layers of artifice that we drape over our lives in order to try and make them more reasonable, more sensical, or work more in our favour are an illusion: the only way to true joy is to embrace life with all its flaws and all four paws.

I hope that Ellie is free now. I hope she dreams of a field that goes on forever, where she can run and run and run and never reach the other side. I hope that she can rest somewhere with stolen socks and smelly old toys, and a thousand corners in which she can flip upside down, her four ridiculous legs poking up in the air like the skyward-reaching masts of a big furry pirate ship. I hope she knows that tonight someone is reading her story, and that she is remembered. We are lucky to have known her.

I feel sad for my friend Robyn, who has lost her mate and companion. I find it hard to look at the smiling dog on the front cover of our book, or to walk past the artwork of her that hangs on the walls of my house, and know that the star of the show is no longer going to come prancing into the room when I visit, looking for that just-right spot to have a lie down in, where she can get herself perfectly in the way of everyone’s feet and ankles. The sky seems a little dimmer today because Ellie isn’t here.

We are going to miss you, Ellie-dog. Thank you for being part of our story, and thank you for letting us be part of yours.

1 note

·

View note

Text

33

In Sydney at Van Gogh Alive. Photo by Georgie Todman.

Yesterday, on the 30th of January, I returned to school for another year. While it seems reasonable to consider the 1st of January as the day upon which everything “ticks over,” as I pick-up the baton for another round of teaching it is this moment that really feels like the fresh start, accompanied, of course, by the reality of growing another year older.

I am thirty-three now. How quickly we start to reach an age that we once thought was impossibly distant. 2022 has been a whirlwind of adventures and runs, teaching and reading, foster care and festivals. I am flat out all the time these days, but I am flat out with everything that makes me happy. As I awaken from a holiday of hibernation and dialing life back, it is exciting for my eyes to burst open in the morning with this swirling thought behind them: there are so many good things I need to do.

Some new challenges face me this year. My co-president Georgie Todman and I have taken on the role of coordinating the Tamar Valley Writers Festival, following the incredible legacy of previous president Mary Machen. Alongside classes, I have a new role facilitating an updated English course and helping to promote reading and the library at my school. I am currently undergoing an Arts Tasmania mentorship with the assistance of the Australian Society of Authors and my mentor, Tasmanian writer Mark Macleod, to continue working on the development of my novel Wombat Overland, and I have some personal goals of my own to chase: I am flat out on the treadmill at the moment trying to get my 5km time to under twenty minutes, and I am hoping to repeat one of my achievements of 2022 and read a hundred books this year (at sixteen so far I think I'm off to a good start!). Those are just the things that I know are coming. If this year is to be anything like the ones that have come before, I have no doubt that there are just as many surprises ahead as well.

So far, even in a school of 1400 students and ninety staff, I have managed to dodge Covid for nearly three years. Nevertheless, my life as a 33-year-old enters strange new realms regardless. Artificial Intelligence has reached a level of sophistication that I suspect will change our lives enormously, and teaching will have to be one of the first areas to adapt, with the implications for writers similarly frightening. The world of the next couple of years will look very different. It's exciting, but it's scary, too.

I concluded my holidays with an interstate trip accompanied by family and friends, zipping over to Sydney to see Michael Sheen at the Opera House in a spectacular performance of Amadeus, then to Melbourne for escape rooms and a re-watch of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child (we had to make sure nothing too drastic had changed in the shorter version). The teenagers that accompanied us surprised me by echoing my own feelings (which I had always felt were probably mine alone) about how disorientating the big city is for people like us who are so used to our small island. We reflected on how much sadness there is on the faces that pass by, how it can make a person feel so very very small. Starting a new year sometimes feels like that: like there is a tide against you, and that it will become too much, and that there is so much hurt in the world that it is hardly a drop in the ocean to offer a small amount of kindness, or to feel awe, or to achieve something.

Oh, I am getting older. My body doesn’t feel it much yet, but it is undeniable. I am more aware with every day how small I am and how the power of my celebrated youth is fading. Nevertheless, I believe I still have a lot to offer. I am here to do what all of us must do: believe that tiny stones create enormous ripples, and that it is our job to help try to cure the curse of loneliness with our actions and our art, clinging to each other in the crowd like survivors in a life raft. As I reach this new beginning, at 33, I am sure you will be pleased to know that I am happy. I am small, certainly, but I am here, and I am glad to be. I write this blog with a cup of coffee, on my birthday, looking out over the city as the streets begin to fill with people and another day—another year—begins.

The world is waking to greet me. The world is waking to greet all of us.

I can’t wait to see what it has in store.

0 notes

Text

AI and the Day Everything Changed

Art from MidJourney.

I remember the night before my family had the internet connected really clearly. I was lying in bed, awake, thinking about the fact that tomorrow my world was going to open up in an entirely new way (I was also thinking quite a lot about the website Neopets, but I have no further comment on this at this time). I was pretty accurate in my assertion, but hours and hours spent playing on computers at Dad’s work, at school, and at my friend Bill’s house had set me up well for the brave new world. The power of being connected to cyberspace had crept up on me. A few weeks ago, I had a similar feeling, but this time it hit fast and hard. I saw something so world-altering that I had to wheel my chair back from the desk, as if my computer might be about to attack me. I could feel my heart racing in my chest. Everything that I thought I knew was going to have to change: teaching, writing and creativity would never be the same. It was exciting, but it was also terrifying.

What I am talking about are the latest advances in publicly available artificial intelligence, specifically, in my case, through ChatGPT and Midjourney. Traditionally, artificial intelligences (or at least those made available to the public) have been relatively static and fairly easy to confuse. Siri and Alexa are handy for a brief weather update, but often they find it hard to follow even the most simple instructions without completely derailing themselves or offering only point-blank refusal. ChatGPT (the “GPT” standing for “generative pre-trained transformer”), as a new competitor in this field, is impressive. It learns fast and it thrives on specificity. My experiments began with simple requests like asking it to write an email to someone apologising that I couldn’t make a dinner engagement. I asked it to suggest some ideas to promote reading in our school library. I asked it to design a day in Hobart and itemise the itinerary in a schedule hour-by-hour. I gave it some basic notes on a student and asked it to write a school report directed at parents.

It didn’t miss a beat.

Then came some more terrifying applications. I asked ChatGPT to write an essay on the symbolism of birds in Trent Dalton’s novel Boy Swallows Universe. I asked it to change its tone to be more critical of the novel and to add MLA references and quotes as evidence. Using Sonnet 18 as a model, I asked it to write another sonnet in the style of Shakespeare about television being bad. I had it designing lessons, and then I got bold: I fed it an example essay and the criteria for assessment and asked it to assess the piece of work and provide feedback. While it’s marking wasn’t perfect (from my perspective at least, but then I do have to wonder in the face of the revolution if maybe I’m the problem here), I would have to call it both fair and reasonable.

Shall I compare television to a poison? It doth corrupt the mind and steal the soul. Its images, like snakes, do twist and coil And with their venom, make us lose control. Sometime too much the screen doth glare and shine, And often is our sense of right dimm'd; But its false promises shall not entwine Our hearts and leave us empty and unfulfilled. Nor shall its lies and violence make us brave, But rather numb and callous to the pain Of others, as we sit and watch and wave Goodbye to all that's real and true and plain. So turn it off, and let the truth be clear, For television doth bring naught but fear.

Chat GPT tries its hand at Shakespeare.

After embracing the gateway drug of ChatGPT, my attention was then diverted to the Artificial Intelligence art generator Midjourney. Midjourney similarly pulls from an enormous database of data it has been trained on in, but in this case it is in order to create pictures. I asked it to design me a book cover for my children’s novel Wombat Overland and the result was gasp-inducing. I gave it the faces of some of my friends and asked it to produce new versions of them as characters from various television and videogame franchises. They looked great. Although there was a lot of filtering and rephrasing, the results were perhaps even more immediately impressive than what I had returned as text in ChatGPT. I have a lot of questions about how this art is generated and the legalities and ethics of its creation, but I can’t deny that its obvious flaws (terrifying faces, hands with six fingers) are completely dwarfed by the high quality of what it gets right. I find myself researching art styles and ideas in order to get input more interesting and unique prompts, and I can do this for hours, saving every image I find beautiful or evocative.

Cover for Wombat Overland as created in Midjourney.

As teachers, AI detectors are going to become essential tools in our arsenal. Luckily these already exist, and are said to be getting smarter in parallel with the AI itself, but my own experiments seem to indicate that they can be stumped pretty easily. I called my brother James to talk to him about the implications of AI in academia and he suggested that after a while most of us will start to develop a sense of the AI voice; certainly I’m already beginning to find that there are telltale signs in its expression and propensity to make pretty head-scratching errors along the way, such as giving me a monthly running plan that had a schedule of eight weeks or including cheese in dairy-free meal ideas. That said, every day these tools are being more utilised and becoming smarter as a result, and we will need to think about how we use them. My mum loved ChatGPT as a tool for reducing busywork, but said she wouldn’t use it to write creatively—she felt it was an assistant rather than a collaborator. I think that’s a fair rule to have, but I have spent a decade of my life with writing as a hobby and feel comfortable leaving AI out of that realm (this blog, you’ll be pleased or sorry to learn, is all me). When it comes to creating visual art, however—something I have never been particularly adept at—it appears that my morals a little more conflicted. I really like making pictures at the press of a button and sharing them with people… but how is that any different to someone using AI to write a poem, except that I personally have a higher level of confidence in writing? Love it or loathe it, we cannot pretend that AI is going to disappear. My prediction is that its use it will become increasingly more common (as common as “Googling” if not more so), and will completely change our lives in ways that are both wonderful and terrible. For now, I think the best thing that we can do is to keep talking about it, to try it and see how it might be useful in our own lives, and to not be afraid to consider critically its implications. Some nights I still lie awake and think about these questions, but honestly, mostly I’m hopeful. I have no doubt that the world still needs its great creatives and thinkers, and certainly it still needs students who can critically and innovatively express themselves and who work hard to compose original thoughts and arguments. This changes the game, and we’re going to have to change with it, but after a few challenging years, it feels like one of the components of a new beginning, and I am excited about the possibilities for where it might take us. Before then, however, there is a lot to think about. The computers are talking to us now, but there are some questions we can only answer for ourselves.

1 note

·

View note

Text

32

Mum is disappointed. “You didn’t write a birthday blog this year,” she tells me.

There must be some mistake. I don’t just “not write” a birthday blog. I have consistently posted something—on my birthday or just after it—for the last decade. In my mission to prove her wrong, however, it doesn’t take too much scrolling to bounce straight back to the post where I turned thirty-one.

There is only one way to fix such a deficit. So here I am, halfway through thirty-two, trying to make sense of what came before.

In 2021, the message was “hold on”. Tasmania got very lucky with coronavirus—in the sense that it quickly and unflinchingly shut up shop to the outside world—but there was also a sense of foreboding: we were always waiting for the fall, floating in a state of uncertainty.

There were some victories. In our bubble, we got to hold each other close. The thing that I was perhaps most grateful for was that I got to walk into classes full of students and teach, almost completely without fear. Ninety-percent of the time school felt normal. It seemed to me that I was like a bird being released into and out of its cage each morning. Covid crept closer to me, with a number of lucky escapes, but I made it, yet again, without the dreaded virus catching me. And of course there were moments to celebrate. There were the students facing what, for many, would be insurmountable odds who nevertheless achieved amazing things: my overall results for school were the best that I have ever had. There was my own achievement in completing the process to qualify me as a respite foster carer. Although thirty-one did not see me leaving the state, there were all of the memories that I created here, running and hiking (with a return to the Overland Track) and exploring its small towns and strange corners with my friends. There was the great thawing of our local arts scene as the years of cancelled shows and events finally came back to life. We still live in an unprecedented time, there is no doubt about it, but at the heart of it we can always find good people.

Now that the borders are open between Tasmania and the rest of the country (and world), the opportunities to travel further are inbound. For now (despite the fears about what coronavirus might do to this island), the trickling in of people I have been without—all returning for the summer months—is a surprise and a delight. I have missed my friends and it is good to have them back. In the meantime, though, I have made a life here that makes me very happy. My definition of family has widened and I have found myself surrounded by individuals who have held me close in a time in which it often felt like people needed to be pushed away. I am so lucky. I am okay.

The new school year is one of mandated mask-wearing and uncertainty, but I choose to face it bravely. In a time in which so much of the fabric of our lives is threaded with fear, it is my sincere wish for all of us that we find strands of hope to cling to. 2022 will not be an easy year (and as someone who is merely pretending not to be halfway through it, I can feel fairly confident in my prophecy here), but the anchors that have always kept us from floating adrift remain available to us: time in the outdoors, good books, family, friends, cups of tea and quiet nights curled up on the couch. I am pleased to announce that in 32 years I have become more relaxed. I am so much less afraid of what other people think of me, and while I still have things to do, and learn, and grow into, I have settled into a life that I love. More awaits, and I am excited for it.

To all of you who have shared the journey with me so far, thank you. As I step through this new doorway into another strange time, I feel confident that, whatever faces me on the other side, if I fall, there will be hands to hold me up, helping me back to my feet.

For all of us, I believe there are better days ahead.

Let’s get after them.

Photo: Georgie Todman.

0 notes

Text

Tamar the Thief

A few months ago, I met with the artistic director of the Tamar Valley Writers Festival, Georgie Todman, and the artist Grace Roberts. Alongside the festival president Mary Machen, Georgie had a very exciting idea: a picture book set in the Tamar Valley that could be shared with children that lived there in their schools and homes.

And that wasn’t even the best bit. The best bit was that they wanted to give it away for free!

In that meeting, we threw around some ideas. Grace told me that she liked drawing birds. I said that I wanted to write a story that was a little bit more human than my last picture book… to give the animals in it clothes and houses and little lives and hobbies all of their own. We ran away back to our burrows to see what we could come up with. Soon, Grace was sending me images that made it clear that she knew exactly how to bring the main character and her world to life. And once I saw how human the creatures that she had drawn looked... I knew exactly where the story went.

The result is Tamar the Thief, the tale of a magpie. Tamar lives by the banks of the River Tamar (kanamaluka) (and yes, it is technically an estuary!). She is alone, stubborn, and defiantly self-sufficient, but beneath it all she knows that she is unhappy. One day she sees something pretty, and she takes it. Surprised at how easy this turns out to be, and how much better it makes her feel for a moment, she quickly falls into a life of crime, and before she knows it she is stealing everywhere she goes! It takes a kookaburra called Luka and a whole lot of patience to get Tamar back on track, and all the while her nest is getting more and more full of all of the things that she has taken, gradually threatening to push her out of the place she once called home…

At its heart, Tamar the Thief is a story about what really matters. Tamar can have anything that she wants in the world, but she discovers in the end that none of it makes up for the feeling she has that something else is missing. Sometimes, it takes moving past the idea of getting what we want in order to find out what we actually need.

I’m really proud of Tamar the Thief and I’m excited to share it with you. I think it’s the kind of story that can remind children and grown-ups about the things that are important, and it gives me no end of joy to see Grace’s illustrations bring it to life, along with iconic locations of the Tamar Valley and even some extra little characters to keep your eyes out for! My huge thanks to everyone who has discovered, read and shared the book already, and to Georgie, Grace and Mary for helping to make it happen.

Tamar and Luka can’t wait to meet you.

You can read all of Tamar the Thief, for free, by visiting the Tamar Valley Writers Festival website here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

A Billion Seconds

If I ever needed reminding about just how absurd a figure a billion is, somewhere in this year following my 31st birthday I am told that I will reach the point where I have been alive for a billion seconds. Oddly, I feel that I can somehow picture my life in these tiny flashes that swirl in the pools of memory and forgetfulness: a billion tumbling, turning moments: of reading, of writing, of learning, of eating, of teaching, of driving, of playing, of dancing, of loving. I have heard it said that if you ask a broad spectrum of adults how old they feel inside themselves, the most common answer is 31, and for me there is certainly a calm comfort in today—perhaps because of the resonance the number has with my birthday on the 31st of January, perhaps simply because of the contentment I have currently found with the place where I live, the people I am surrounded by, and the vocational and artistic lives I have forged for myself.

My thirtieth year might be described as the beginning of the “roaring twenties” only in the sense that it was categorised by the blare of news bulletins and the squealing of sirens. At this time last year, smoke still circled my city from close and distant infernos of flame, and we had to entertain the frightening possibility that the trend of the apocalyptic Australian Summer might be a recurring new reality. A colleague once promised me that every year of teaching got easier, and for the first five weeks of 2020 I felt the satisfied joy of finally feeling a steady command of my profession, with a year’s internship and another full year’s teaching behind me. Then, before I knew it, I was tumbling into a world of chaotic phone calls, of paranoia and aching eyes forced to host classes on Zoom and email at absurd rates. On a global scale, I know, my own challenges are not significant, but that didn’t mean that I was safe from frustration, exhaustion, doubt and despair. The first Monday morning when I finally walked into my Line 1 English classroom and found it full of students again I barely contained my emotion, and as I wait to meet this year’s students I am trying to remember that promise of gratitude in the moments that are so exhausting and so easily taken for granted. There are certainly achievements to celebrate in 2020: my involvement in the Tamar Valley Writers Festival, hosting their podcast alongside Annie Warburton, and the continuing evolution of my own writing, which ticks away (usually) secretly but with deep contentment, as well as friendships and adventures and beautiful moments spent in the wild.

A billion seconds might seem like an absurdly long time, but I know that time moves faster the more of it you have tailing you. I try not to obsess over the memories that swirl in the pool and follow me now, nor the rhythmic, constant ticking of the clock above my desk where I write. A billion good seconds are behind me, and hopefully there are at least a billion more ahead. I’ve got work to do, and work that will hopefully make good use of the years and minutes and moments in front of me.

The trick—it seems to me—is not to count that steady passage of time, but to make it count, and I feel lucky on this day for the seconds for the time that I have had. In all the ways that matter the most, it is undeniable: I am a billionaire. (Photo by Georgie Todman.)

0 notes

Text

New Normal: Thoughts on the Arrival of 2021

And so we reach the coming of age of our new millennium. It is hard to imagine on this still morning that brings in 2021 the horror we faced at this time a year ago, gasping helplessly as an inferno rolled across the country, an event that felt apocalyptic and earth-shattering but which we told ourselves was undoubtedly the year’s tragedy—perhaps one that would be back as we adjusted to life with the global air-con on the fritz, but nevertheless something endurable and ending, at least in the short term. Yet it only took a couple of months before 2020 dealt another punch, however, and the year was suddenly epitomised by the image of a mask, the word “lockdown,” by measurements of 1.5 metres and by free-standing hand santitiser dispensers that stood in every doorway like some kind of traditional decoration for a festival celebrating cleanliness. One of my colleagues made a habit of asking everyone about their “new normal,” and yet none of this felt “normal” at all… Most of us had only one wish when it came to that word, and that was for things to return, as soon as possible, to the way that they were before.

And still, somehow, we endured. Last night as the clock struck midnight I watched the world from a balcony above the ocean, seeing the fireworks in the distance rise into the sky like promises of light, the moon standing high and hopeful and casting a warm glow over the bay as the teenagers at the shack a few doors down the road danced and cheered and kissed in silhouettes around the window. I know that life does not divide itself into neat, clear-cut sections, but there is something calming about the number one as I watch the calendar tick over, like a fresh exercise book on the first day of school or some glorious moment of raw discovery and potential: like seeing an animal you never knew existed. Everything can be new on the first day of a new year. Everything can be normal, just for a moment.

And so, to my wish for this year. I hope that in 2021 we find ourselves a new normal—maybe even a beautiful one. I hope that the lessons of 2020 are not ignored or forgotten, and that we remember that we remain in a fragile balancing act with this planet that sustains us, and in a fragile balancing act with each other. I hope that we continue to recognise that a hug or a coffee or a walk in the outside world is a simple thing when it is free but can come at great cost, that stories fight loneliness, and that ultimately to be human is merely (and hugely) to create tiny threads of connection in the lives of others. Our fears and challenges in the world of 2020 are not over, and the greatest danger of a new normal is of course that it never exists in the first place, and that we stumble violently and defiantly along our old patterns of behaviour, pretending that there are no consequences to doing so. I hope instead that we follow a different path and take the world as it is, finding little ways to make it more endurable, more hopeful, and better.

The great lesson for me in the darkest hours of this year was that fear and sadness are not easily borne alone, and that even small instances of kind voices on the phone or a shared experience can save a day, which can save a month, and save a year. Thank you to all of you who have been there for me in 2020. I have learnt to be more grateful for my friends than ever before, and to cherish those moments of shared love, sadness and laughter, when the rest of the world falls away and disregarding whatever chaos swirls in the storm outside there is a little moment of normality.

I hope this round brings joy and beauty. Happy New Year to all of you, and happy new normal.

0 notes

Text

The Thorns in the Holly

One of the fascinating things about writing is that it captures a moment that sometimes cannot be understood to exist outside of the context that it was created in. As I scroll back through my posts commemorating the beginning of this new decade at the end of last year, it is almost laughable how naïvely they look towards 2020 as another year that might be a blank slate, on which might I could write anything if I were to show enough diligence and perseverance to my goals and dreams. These thoughts seem, on reflection, less like a promise and more like a hopeless wish for deliverance screamed into an uncaring avalanche. And yet, here we are.

I can remember the first five weeks of the school year, as well as the excitement and confidence with which I embraced them, feeling finally that I had some self-assurance in the classroom and that things really would be easier this time. I can remember the early whispers of coronavirus—an intriguing development from a far-away place that gradually, then quickly, spread like a growing coffee stain across a map of the world. I work with colleagues who have never—in decades of teaching—seen a school closed down for any extended period of time, and yet suddenly we all faced a reality that could not be denied. I taught sections of this year over YouTube, Zoom, across Canvas and through phone and email. I scrambled to catch up those who fell off the radar or who struggled with the challenges of isolation and supporting their family, staying healthy and being creative—the same challenges that I faced, too. There have been tears, and nights and days of panic, but there have also been moments unexpected hope, growth, and strength. I begged my fifty English 3 students to sit their exams, and my greatest moment of optimism this year was watching every single one of them enter that exam hall. I feel like I have been cheated out of a large chunk of the all-important time I would usually get to spend with them, and yet somehow I look back on 2020 with the same intense joy and pride that I always have. Some of my students may think that I rescued them this year, but the truth is that they rescued me.

I am late with everything this Christmas. The lights were put up outside a week ago, the tree was frantically assembled a few days ago, the presents scrambled into piles out of the corners of cupboards and finally wrapped last night. I am increasingly skeptical that the world will ever be able to go back to the way it was, but perhaps this sharp interlude, this change to our way of life, reminds us of a few things that are so easily forgotten: that we rely on the kindness of strangers, that we must find joy in even the darkest times, that we inhabit this planet as guests, and that hand sanitiser is liquid gold. 2020 threw up its fair share of challenges, but it also provided opportunities—I joined Annie Warburton as host of the Tamar Valley Writers’ Festival Podcast, I began a series of new projects of my own, and I read more than I have for perhaps a decade. I stayed connected or re-connected to old friends, and I even somehow managed to make some beautiful and surprising new ones. It is another year in which my life is richer at its conclusion than it was at the beginning, and that is something I don’t take for granted.

My thoughts in this moment are with those for whom Christmas will be unrecognisable from previous years—isolated, cut-off, or mourning. I know that I am one of the lucky ones, and if this frantic year has taught me anything it is a healthy respect of gratitude. This might have been ten years for all of the memories and challenges that it managed to hold in a simple twelve months, or it might have been a blink of an eye, but I am here, and Christmas is coming, and in the darkness of the night the pulsing globes on my path and the tree in my window shine like a beacon that calls me back home, as if to say: Up here. Up here. I know it’s been hard but the light is still alive.

All my love to you and yours. Merry Christmas.

(The gorgeous image that headlines this blog post is from Ben Lambert, who I collaborate with on a comic-in-development titled Tangled Pines. Ben is working so hard on it, and I’m so excited by his progress. Stay tuned.)

0 notes

Text

Bees, Keys, Stories and Seas: THE STARLESS SEA by Erin Morgenstern

“How are you feeling? Zachary asks.

“Like I’m losing my mind but in a slow, achingly beautiful sort of way.”

There are books that you read, books that you love, and books that you carry around with you, but only very rarely does a book emerge that does something more… that feels like it has reached inside your brain and rearranged things a little bit—leaving some extra space to help you imagine something bigger. The Starless Sea is one of those books.

Erin Morgenstern’s debut novel The Night Circus began with the line ‘The circus arrives without warning.’ A captivating opening, it was also a fitting description of the author herself, who appeared suddenly and rose meteorically with a brilliant debut that combined the fantastic and the romantic in a way that felt like the literary equivalent of drinking hot chocolate by a roaring fire. Her audience waited with bated breath for eight years to see what would arrive next. The result does not disappoint.

The Starless Sea is the story (or stories) of Zachary Ezra Rawlins, a young man who finds a curious book titled Sweet Sorrows at his university library. The book is complex, puzzling and beautiful… It is also clearly—at least in part—about him. In trying to decipher how this could be, Zachary stumbles across a hidden subterranean world where stories are born, protected, and occasionally ended, and thus begins his own journey to discover how his particular narrative ends. It’s all very meta, and in the hands of a less adept writer The Starless Sea might be accused of shameless pandering to its audience. In Morgenstern’s hands, however, it proves itself: as with The Night Circus, it calls back to a writerly tradition of the likes of Ray Bradbury, where every line is not only important, but also beautifully constructed. Like Carlos Ruiz Zafon’s The Shadow of the Wind before it, it proves itself worthy of the significant leap of authorial faith to aspire to be a beautiful story about beautiful stories.

To say even something as simple as that I understood all of The Starless Sea would be a gross overstatement, but on an initial read understanding hardly seems the point. The novel is a puzzle box, carefully layered and constructed in its own particular way so that narratives echo and intertwine and rhyme with each other. In a world in which we often read books as if they are to be used and discarded, it feels liberating to say that The Starless Sea is not the kind of novel that you might want to pick up in an airport and leave in a hostel on the other side of the world. Its secrets lie deep and require careful untangling: I think I could read it every year and find a different strand every time to pull from the knot of it. The characters are compelling and seductive, and perhaps my only criticism of the book was that I hoped that the text I was holding would have some kind of storyworld significance, so that the novel itself became an artefact of the story it expresses.

Nevertheless, I buy copies of The Starless Sea in the same way that you might buy tickets to the moon if you knew you could have them for the mere thirty dollars that is this novel’s asking price. I give it to people for two reasons: one, because I think it’s beautiful and is so much more experiential than most books; and two, because when you come across a book that is this strange and special you don’t just want people to read it, you also want to be the one who gives it to them, like the entry key to a secret door.

The Starless Sea eschews the masculine fantasies of the past for something much gentler. Gone are knights on horseback who dream of death and glory, and instead we find the invention of the new and creativity, mythology and history hailed as the ultimate forms of strength. In stories, Morgenstern seems to be arguing, we find true magic, which has been with us all along.

The Starless Sea proves this thesis. What a spell she has woven.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

20... 20... 30

Where did I think that I would be when I rose this morning on my thirtieth birthday? Would a younger version of me be satisfied with this man that stares back at him from the mirror? How would he interpret the fact that I have exceeded some of his hopes and dreams by a wild margin, while others still sit far away from him, with uncertain potential?

As I head into a new phase of my life, it has begun to feel that I am discovering where I both want and need to be. Once, I told myself that teaching was a back-up plan, a concept that felt like a lazy compromise to even contemplate, and that hovered in the background of writing as a last resort. Now, I cannot imagine my life without its two married halves, and my first “real” year at Launceston College was my favourite so far. I have dedicated my days to the challenge of illiteracy in our country and the neglected power of story. I see all of my little pieces as connected the jigsaw of my larger identity, and I would be hard-pressed to choose one at the expense of the other. I missed school as the holidays wound to a close, and it makes me happy to be back there now, printing and organising in anticipation of the students returning next week.

The evidence of other people who have crossed this milestone seems to suggest that lots of people enter into a crisis when they turn the age that I find myself reaching today. They seem convinced that their best days and their best health are behind them, the follies of youth giving way to harsh reality and adult expectations. I don’t know why I don’t feel that. Somehow, the expanse of time in front of me seems wonderfully distant and full of potential, while the stretch of time behind me feels full and rich and long. I sit and compose this at my small, simple desk in a quiet house that overlooks Launceston, where I type each morning as the sun rises and the city wakes in my periphery. I have developed the good habits that I always hoped for and worked towards: I meditate, I stretch, I write, I run, and I have friends and family who I love and make time for.

I would never pretend that I have suffered much. I have been incredibly fortunate, and continue to get luckier as each new day becomes even more crowded with wonderful people. Nevertheless, my twenties were sometimes a strange time, marked by solitude, uncertainty and occasionally big questions of purpose. I think about that young boy, reading books and dreaming. I think about telling him that I am a teacher, and that my first book was published before I crossed this line into a new decade.

I don’t know that he’ll care all that much. Really, he will only have one question that warrants answering; a question that many of us obsess over, defining and strategising and unravelling…

Are you happy? he will ask me.

Yes, I can tell him. Yes.

And truly I am.

(📸: At the launch of Becoming Ellie, with Graeme Whittle, our publisher from Forty South Lucinda Sharp, and Ellie herself. Photo taken by Kate Tuleja.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A 2020 Vision

In the late, great Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Ford Prefect tells Arthur Dent that “time is an illusion” and “lunchtime doubly so.” The new year sometimes feels just like that: an illusion, a fabricated creation where a year or a decade ends and begins. Perhaps these little rituals we have—these resolutions and intentions and goals—are just another thing we’ll have in the bin by the end of January, along with the final scraps of our Christmas leftovers. Yet for me the delineation has always meant more than that: I take my goals and resolutions seriously. I like closure and I like new beginnings. To me, a new year feels like opening a brand-new exercise book always did when I was a child… Arbitrary or not, it speaks of a fresh start.

In all of the ways that I know how to measure these things, 2019 has been my most successful, rewarding, happy and fulfilling year. I have loved every moment of it, and I am sorry to see it go, but equally excited to see what comes next. What do I hope for from this new year and decade? On a personal level, I have all of the usual things in my notebook: the commitment to exercise and good diet, devotion to work (including my own creative work), setting time aside to refresh, to grow, and to take pleasure in friends and family and art and the things that renew me. I want to stay optimistic, particularly as a teacher, and to continually rekindle and ignite my enthusiasm for all of things that I do and love; to focus on hard work and kindness in everything that I do. Specifically, this year I want to be clearer and more deliberate in the way that I spend my time helping others and make a greater effort to support financially charities that I feel are doing important work. My life is increasingly socially-driven, and the fatigue of a thousand micro-interactions can often be incredibly draining. I want to remind myself that in each moment and with each person I must always be curious, always wanting to know more and examine the gaps in my own perception—listening, rather than merely waiting for their own chance to speak.

I have dreams for the world this year, too. In Australia this summer we are seeing the horrific devastation of bushfires, intensified dramatically by extreme weather conditions. No matter what our differing beliefs are on the causes and consequences of the fires that blaze throughout our world, I deeply hope that we can reverse some of our exploitation of this beautiful planet. I would love for those of us who vote this year to have the courage to vote with the earth in mind, to work a little harder to minimise the waste that we produce and the amount of resources that we consume and exploit. For my part, I will be focusing on minimising and managing my travel plans and consumerism while shifting my eating habits to vegan for a majority of my meals. This year I loved reading John Marsden’s The Art of Growing Up, and in a world that continues to denigrate its young people (very much in keeping, I’m sorry to say, with cultural norms of a hundred generations before us), I would love us to turn our perceptions away from “snowflakes” and “self-absorbed teens” and a “lack of resilience” and actually listen to what our young people are asking of us and need from us. No generation is perfect, but as someone who works with teenagers every day I can attest to the way that they have continued to inspire me with their amazing compassion, their creativity, their profound forms of expression, their awareness, their acceptance of each other, and their desire to see things change for the better. In this regard, too, part of my pledge for the coming year is to believe in the students that I have the privilege of teaching: to listen to them, and to not look down on them or take them for granted. The world will one day be theirs, and we have created a lot of work for them—sometimes the best thing that we can do to help is simply to clear the way.

2019 has been particularly kind to me, but I accept that this is partly a matter of simple good luck. I know that for some of you the year will have been challenging—even incredibly difficult or heartbreaking—and that you walk into the twenty-twenties with cautious steps. If nothing else, I hope that you can be kind to yourself this year. We have become so well-attuned in our lives to the needs of others that we sometimes forget that we must fill the cup for ourselves as well. I hope that you take time to do the things that you know will renew you: to read wonderful books, to listen to an album that you once loved but had almost forgotten about, to reach out to a friend you miss, to hold an animal or a baby in your arms, or to take a moment by yourself in nature, simply to be with the world as it already was—long before you were ever part of it—with no expectation of needing to capture or share it.

I know that there is a lot that we can feel despair about, but as we enter this new era we must also recognise in the simplest terms that the world exists as it is in this moment, and optimism, hope and action are our only ways forward. Personally, and collectively, as with every new beginning, we must turn ourselves to a bigger question:

What do we want to become?

Happy new year to all of you. I hope it’s a cracker.

(📸:Me in my natural habitat, taken by Kate Tuleja.)

0 notes

Text

29

Photo by Kate T. Creative.

I have a tradition. On my birthday, I reflect here on the year behind and look to the year ahead. Every ending and beginning of a chapter is arbitrary of course, but that doesn’t mean that it’s not helpful to have them. They break up the longer story.

Last January 31st, you might have noticed that my usual birthday post never surfaced. I wrote it, but I kept it in the archives. I didn’t like what it said about me. Things were changing: I had made the hard decision to leave behind the excitement and opportunity of the world of television and the generous people I had worked with, and to instead embrace the world of teaching. Yet I had tried to become a teacher before. What did stating it again really say about where I would be in a year’s time? Would I still be writing, or would that part of me—a part that I had always been so open about as the beating heart of what I do, and that you have all been so supportive of—become smothered, or lead to some kind of horrible crisis and ultimatum?

And so I simply rode the waves of the year, beginning in my new role as an intern in the English Department at Launceston College. I had three big goals for 2018: explore my passion for teaching with everything I had, finish my full-time studies, and write a book. If I could do all of those things, I considered, then perhaps I really could live this mad life long term, and I wanted that desperately.

So I did it. With the help of my mentors at college I gradually deepened my role until I could take my own classes, I graduated uni with marks at the standard I had set long before setting foot in the classroom, and the fourth draft of my latest novel, Wombat Overland, waits to be filed in the post this week and submitted for this year’s Text Prize.

I love it. I love the financial freedom to write whatever I please and worry about publishing afterwards. I love the structure and purpose to every day—the leaping out of bed at 6am every morning to pen words like these because there is simply no other chance in the madness of a day filled with people and learning. I love my colleagues and my school, and I love my students. All day, I talk about the magic of language and stories to the minds of tomorrow, and there is no greater gift I could be given on my birthday. Luckily, Launceston College has taken me back for another year, and next week when the students arrive it all begins anew. Chapters are arbitrary, and like so many before me I have discovered that the line between a writer and a teacher is another one of those false separations. I do not (for now, at least) forsee a future where I am not both, and each to the benefit of the other.

I am about to click the post button, and I don’t feel the same fear that I felt last year. I’m excited. Perhaps this particular chapter of my journey will see changes—I’d be shocked if it didn’t—but I’m starting to feel that wheels that began their motion a decade ago are finally rolling towards the place where they need to be.

I am so lucky. Those of you who have nagged me for years about a book being published, I hope the day is coming. Still, I can say definitively: I am teaching, I am writing, and I am happy…

On my birthday, and all of the other days that go with it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Two Weeks Writing Beside Cradle Mountain

As I drive the winding road to the cabins of Waldheim I must bump a button somewhere. The CD player starts to play Miriam Stockley’s “Perfect Day.” I recognise it from the opening of the TV series of The World of Peter Rabbit and Friends, where a young Miss Potter started each episode wandering amongst lush green fields and into the farmhouse to have some tea with her rabbit. It feels like a good omen.

Like the novel I’m writing, my own story begins in the snow. The world is becoming increasingly white as I arrive at the chalet, and when I open the cabin where I am staying for two weeks and get the heater going, I am mesmerized by the silently falling flakes outside the window. There is no phone reception, no television, and while the occasional friend or visitor pops in when I’m in desperately in need of some human interaction, for most of my stay there is only me, a pile of children’s books with animals as their heroes, a phone full of podcasts and the lumbering 70,000 word first draft of a new novel that I have brought with me. A man I meet outside in the snow tells me that he admires my discipline. I explain that it’s easy to have discipline when there is literally nothing else to do.

Over the course of the school holidays I spend most of my time in the world of Wombat Overland. The novel is the story of a wombat who discovers another of his kind has died in the snow outside his burrow, with a joey surviving in her pouch. The only other item in her possession is a curious map to Lake St Clair which identifies the edge of the lake as “home.” The old wombat decides to take the child back there, embarking on an odyssey which aligns neatly with the locations that a human walker would discover on their own journey on the Overland Track. I stay in one of the Waldheim cabins at the generosity of Arts Tasmania and the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service. The solitude provides a beautiful opportunity to dive deep into the story, and by the end of the second week my 70,000 word first draft is a 40,000 word second draft, then a third draft, and then a fourth.

In another piece of accidental and wonderful synchronicity of life imitating art, every day I walk down to Ronny Creek to pick up a precious bar or two of phone reception. Every day I stroll past a mother wombat and her joey, and every day they allow me to get a little bit closer before waddling away to a safer distance. Eventually the weather closes in—a dripping, drenched day where everything is slippery and treacherous—and it hardly seems worth soaking through to the skin just to try and clear the spam folder of my inbox with sodden, crinkly fingers. That night I open the door of my cabin to go to the bathroom and shine my headtorch out into the darkness. The mother and her baby are there; eyes blinking at the sudden light, hiding from the rain under the ledge of a shed and waiting indignantly. I am struck by the thought that this is what writing is like sometimes: sneaking ever closer to a wild creature, and then finding one day that it is now coming to you instead.