journal of Urology & Nephrology: The journal covers the topics like epididymal cyst, microdot surgical vasectomy reversal, ultrasound, Renal failure, uro-oncology, Urogynecology, sepsis, prostate diseases, prostate cancer, etc: Lupine Publishers Journals.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Lupine Publishers | The Early Treatment of a Bodybuilder with Symptomatic Chronic Renal Failure with Intestinal Dialysis: A New Recommendation for Intestinal Dialysis Enhancement

Abstract

Background: Dietary therapy aiming primarily at reducing the generation and accumulation of urea through protein restriction is the most important non-dialytic therapeutic intervention in the management of chronic renal failure. The use of a urea lowering agent “acacia gum” with protein restriction has been increasingly used as a new form of dietary dialysis which has been increasingly known as intestinal dialysis. Just like in other forms of dialysis, the use of conservative dietary and pharmacological measures is also necessary in intestinal dialysis.

Patients and methods: The early treatment of a bodybuilder with symptomatic chronic renal failure with intestinal dialysis is described, and the relevant literatures were reviewed with the primary of identifying the evidence that can contribute to enhancing intestinal dialysis.

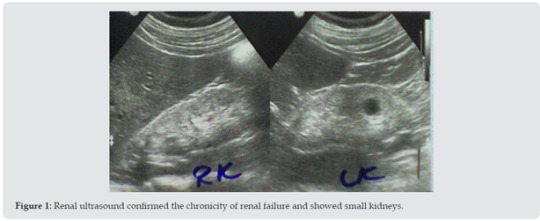

Results: At about the age of 50 years (March, 2022), a professional bodybuilder who presented with progressive symptomatic uremia associated with nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and mild anemia. His weight was about 100 Kg, and before his current illness he reported that his bench press single maximum repetition was 140Kg. On the 19th of March, blood urea level was 162 mg /dL and serum creatinine was 6.2 mg /dL. Renal ultrasound confirmed the chronicity of renal failure and showed small kidneys. The conservative dietary (Acacia gum supplementation plus very low protein diet) and pharmacological managements were prescribed according to the latest published intestinal dialysis guidelines and included oral iron and folic acid capsule, and calcium carbonate. After two weeks, the patient was asymptomatic and blood urea was lowered to 126.4 mg/dL, and the hemoglobin was increased to 11g/d.

Conclusion: This is just another case to demonstrate that intestinal dialysis is effective in lowering blood urea level and improving symptoms in symptomatic chronic renal failure. There is a convincing evidence to support that the addition of essential amino acids and ketoanalogues in the management of chronic renal failure with intestinal dialysis can contribute to its enhancement.

Keywords: Symptomatic uremia; Intestinal dialysis; Ketoanalogues of essential amino acids.

Introduction

Dietary therapy aiming primarily at reducing the generation and accumulation of urea through protein restriction is the most important non-dialytic therapeutic intervention in the management of chronic renal failure. The use of a urea lowering agent “acacia gum” with protein restriction has been increasingly used as a new form of dietary dialysis which has been increasingly known as intestinal dialysis. Just like in other forms of dialysis, the use of conservative dietary and pharmacological measures is also necessary in intestinal dialysis [1-14].

Patients and methods

The early treatment of a bodybuilder with symptomatic chronic renal failure with intestinal dialysis is described, and the relevant literatures were reviewed with the primary of identifying the evidence that can contribute to enhancing intestinal dialysis.

Results

At about the age of 50 years (March, 2022), a professional bodybuilder who presented with progressive symptomatic uremia associated with nausea, vomiting, pruritus, and mild anemia. He was not havening reduction in urine output, edema or hypertension. His weight was about 100 Kg, and before his current illness he reported that his bench press single maximum repetition was 140Kg. On the 19th of March, blood urea level was 162 mg / dL and serum creatinine was 6.2 mg /dL. Urinalysis showed 2 plus albuminuria and one plus amorphous urate. Blood calcium and serum electrolytes were within normal ranges, but he had mild hyperphosphatemia with serum phosphorus of 4.9 mg/dL (Normal range 2.4-4.4mg/dL). Hemoglobin was 10.7 mg/dL (Normal ranges: 11.5-16.5 g/dL). Liver function tests were normal (Total serum bilirubin 0.8 mg/dL, Aspartate aminotransferase (SGOT) 25 iu/L, alanine aminotransferase (SPOT) 21 iu/L, alkaline phosphatase 284 iu/L).

He reported history of episodes of hyperglycemia that in the case of bodybuilders is generally attributed to growth hormone administration in excessive doses. However, the patient was reluctant to provide details about the performance enhancing medications such as anabolic steroids and growth hormone, and he was not confirming or denying the use of such agent. He was simply saying that he was taking protein supplements. Renal ultrasound (Figure 1) confirmed the chronicity of renal failure and showed small kidneys (RK: 8 x 4, cortex 6 mm, LK: 8.2 x 4, cortex 6 mm). The kidneys had hyper-echoic texture with reduced cortical thickness and loss of the cortico-medullary differentiation. There were small cysts on both kidneys, not more than 1.5 cm in diameter. Abdominal ultrasound also showed small polyp in the gall bladder and mild enlargement of the prostate with a volume of 27 cm3 (Normally up to 25). The patient initially required oral prochorperazine 5 mg for two days control the nausea and vomiting, and oral antihistamine plus topical crotamiton 10% to control pruritus. The conservative dietary (Acacia gum supplementation plus very low protein diet) and pharmacological managements were prescribed according to the latest published intestinal dialysis guidelines and included oral iron and folic acid capsule, and calcium carbonate. He also received oral finasteride 5 mg daily for the prostatic enlargement. After two weeks, the patient was asymptomatic and blood urea was lowered to 126.4 mg/dL and the hemoglobin was increased to 11g/d. Ultrasound showed normal prostate size of 20 cm3. Literature review suggested that the addition of essential amino acids and ketoanalogues in the management of chronic renal failure with intestinal dialysis can contribute to its enhancement. Therefore, Ketosteril (Fresenius), was prescribed in a low initial dose of three tablets, and was ordered to be brought to the patient from Turkey.

Discussion

Until now, there is no evidence to support that high protein diet per se can cause chronic renal failure. However, nephrocalcinosis caused exogenous vitamin D intoxication was reported to cause renal failure in a bodybuilder athlete [15]. Therefore, an accurate causation of the chronic renal failure cannot be determined. Carrero et al (2020) emphasized the importance and benefits of fruits and vegetables in patients with chronic renal failure. The intake of fruits and vegetables is associated with a higher fiber intake which can cause a shift in the gut microbiota towards reduced production of uremic toxins. The intake of fruits and vegetables is also associated with lower intake phosphorus, and thus help in controlling hyperphosphataemia [16]. However, the latest published intestinal dialysis guidelines have already suggested intake of fruits and vegetables [17]. The use of Keto-analogues of essential amino acids in the management of chronic renal failure has been reported as early as the 1970s (Walser, 1978; Bauerdick and colleagues, 1978, Giovannetti et al, 1980) [18]. Bauerdick and colleagues (1978) reported the use of nitrogen-free hydroxy and keto precursers of amino acids in the treatment of patients with chronic renal failure with essential amino acid and a low-protein diet was associated with a more positive nitrogen balance [19]. In 1980, Giovannetti et al treated twenty patients with advanced chronic renal failure with a low protein diet (0.2 g/kg/day hour vegetable proteins) and essential aminoacids and ketoanalogues. They reported that treatment was associated with a favorable outcome [20]. In 1981, Barsotti et al emphasized that treatment of chronic renal failure a very low protein diet plus essential amino acids and ketoanalogues is not associated with reduction of creatinine clearance, while treatment with hemodialysis and free protein intake is associated with reduction of creatinine clearance. They treated thirty-one patients with a conventional low-protein diet, and treatment was associated with a linear reduction of creatinine clearance. A thirteen patient treated with hemodialysis experienced significantly accelerated decline of creatinine clearance. However, only one of a twelve patients treated with a very low protein diet supplemented plus essential amino acids and ketoanalogues, experienced continued a continued reduction in creatinine clearance [21].

Mitch and colleagues (1982) described the treatment of 9 patients who severe chronic renal failure (mean glomerular filtration rate 4.8 ml/min; mean serum creatinine 11.3 mg/dl). They were treated with protein restriction (22.5 g daily of mixed quality protein) plus essential amino acids and keto-analogues of essential amino acids including tyrosine, ornithine, and a high proportion of branched-chain ketoacids, and very little methionine. Phenylalanine and tryptophan were not provided. One month of treatment was associated with significant lowering of serum urea nitrogen. Hyperphosphatemia which was observed in three patients, improved. Treatment was not associated with side effects. The treatment precluded the need for dialysis in patients with severe chronic renal failure who would otherwise need dialysis [22]. In 1983, Barsotti et al described the treatment of 48 patients with chronic uraemia for a maximum of 36 months with low protein diet plus essential amino acids and keto-analogues. Ten patients experienced reduction of renal function and required dialysis.

Eight patients experienced difficulties in complying with treatment and also required dialysis. Three died for causes that are not directly related to renal failure. 27 patients continued with treatment without important reduction in renal function, and enjoyed satisfactory subjective and objective states without evidence of protein malnutrition or unwanted effects [23]. In 1985, Barsotti et al reported that the treatment of men who had uremia with a low protein diet plus essential amino acids and ketoanalogues was associated with restoration of testosterone levels in blood [24]. In 1985, Ciardella et al described the treatment of eighty-five patients with chronic renal failure with a vegetarian low-protein, low-phosphorus diet plus essential amino acids and ketoanalogues. Treatment was associated with marked reduction of serum triglycerides in the 61 men, but the reduction was not significant in woman. When the patients were later treated by maintenance hemodialysis without dietary restrictions, the experienced elevations in serum triglycerides levels which was attributed to the loss of the effect of the dietary restriction on uremic male hypogonadism [25].

Conclusion

This is just another case to demonstrate that intestinal dialysis is effective in lowering blood urea level and improving symptoms in symptomatic chronic renal failure. There is a convincing evidence to support that the addition of essential amino acids and ketoanalogues in the management of chronic renal failure with intestinal dialysis can contribute to its enhancement.

Conflict of interest

None.

For more Lupine Journals please click here: https://lupinepublishers.com/index.php

For more Journal of Urology & Nephrology Studies articles please click here: https://lupinepublishers.com/urology-nephrology-journal/index.php

#lupine publishers#articles#urology#submission#lupine journals#journal of urology & nephrology studies#open access journals#nephritis#nephrology#juns

0 notes

Text

Lupine Publishers | Briefly about The Ureter

Abstract

Every man has two kidneys. Each kidney has a ureter, which drains urine from a central collection point into the bladder. From the bladder, urine is excreted through the urethra from the body through the penis in men and the vulva in women. The most important role of the kidneys is to filter metabolic waste products and excess salt and water from the body and help remove them from the body. The kidneys also help regulate blood pressure and make red blood cells.

Keywords: Kidney; Obstruction; UTI; Injury

Introduction

The ureters are tubular structures responsible for the transportation of urine from the kidneys to the bladder. The length ranges from 22 to 30 cm, and they have a wall made up of multiple layers. The innermost layer is made up of transitional epithelium, surrounded by the lamina propria, which is a connective tissue layer. These two layers make up the mucosal lining. The next layer is made of smooth muscle that, as mentioned previously, is continuous with that of the calyces and the renal pelvis. However, one slight difference is that within the ureter, the smooth muscle layer is divided into an inner longitudinal and an outer circular layer. These muscular layers allow peristalsis of urine. The outermost layer is the adventitia, which is a thin layer enveloping the ureter, its blood vessels, and lymphatics. The ureter is often divided into three segments: the upper (proximal), middle, and lower (distal) segments. The upper segment starts from the renal pelvis to the upper border of the sacrum. The middle segment is the part between the upper border and lower border of the sacrum. The lower segment is from the lower border of the sacrum to the bladder.

Anatomy

Each ureter lies posterior to the renal artery and vein at the ureteropelvic junction [1]. They then descend anterior to the psoas major muscle and the ilioinguinal nerves, just anterior to the tips of the lumbar transverse vertebral processes. Approximately a third of the way down, the ureters are crossed by the gonadal vessels. They then cross the bifurcated common iliac arteries and run along the anterior border of the internal iliac artery toward the bladder, which it pierces in an oblique manner. It is this oblique entry of the ureter into the bladder, the intramural segment of the ureter that acts as a nonreturn valve preventing vesicoureteric reflux. This valve can be congenitally defective such as that seen in those with short intramural segments, or rendered ineffective as a result of injury, such as surgery or disease, all of which leads to reflux. Many congenital abnormalities of this oblique tunnel are seen in association with a duplex kidney and ureterocoele. In its lower third, the ureters pass posterior to the superior vesical branch of the internal iliac artery also called ‘umbilical artery’. On the right side, the ureter is related anteriorly to the second part of the duodenum, caecum, appendix, ascending colon, and colonic mesentery. The left ureter is closely related to the duodenojejunal flexure of Treitz, descending and sigmoid colon, and their mesenteries.

Obstruction

The diagnosis of obstruction cannot be made on the basis of haematological or biochemical tests [2]. There may be evidence of impaired renal function, anaemia of chronic disease, haematuria or bacteriuria in selected cases. Ultrasonography is a reliable means of screening for upper urinary tract dilatation. Ultrasound cannot distinguish a baggy, low-pressure, unobstructed system from a tense, high pressure, obstructed one, so that falsepositive scans are seen. A normal scan usually but not invariably rules out urinary tract obstruction. If obstruction is intermittent or in its very early stages, or if the pelvicalyceal system cannot dilate owing to compression of the renal substance, for example by tumour, the ultrasound scan may fail to detect the problem. Radionuclide studies may be helpful. If obstruction has resulted in prolongation of the time taken for urine to travel down the renal tubules and collecting system (obstructive nephropathy) this can be detected by nuclear medicine techniques and is diagnostic. Conversely, in the presence of a baggy, low-pressure, unobstructed renal pelvis and calyceal system, nephron transit time will be normal, but pelvic transit time prolonged. If doubt exists, frusemide may be administered; satisfactory ‘washout’ of radionuclide rules out obstruction and vice versa. Relative uptake of isotope may be normal or reduced on the side of the obstruction and peak activity of the isotope may be delayed. In general, absence of uptake of radiopharmaceutical indicates renal damage sufficiently severe to render correction of obstruction unprofitable. Isotope studies may thus provide a guide to the form of surgery to be undertaken. Antegrade pyelography and ureterography are extremely useful in defining the site and cause of obstruction and can be combined with drainage of the collecting system by percutaneous needle nephrostomy. The risk of introducing infection is less than with retrograde ureterography in which technique instrumentation of the bladder is followed by injection of contrast into the lower ureter or ureters. This technique is indicated if antegrade examination cannot be carried out for some reason or if there is a possibility of dealing with ureteric obstruction from below at the time of examination. Ureteral obstruction occurs in 2–10% of renal transplants and often manifests itself as painless impairment of graft function due to the lack of innervation of the engrafted kidney [3]. Hydronephrosis may be minimal or absent in early obstruction, whereas low-grade dilatation of the collecting system secondary to edema at the ureterovesical anastomosis may be seen early post-transplantation and does not necessarily indicate obstruction. A full bladder may also cause mild calyceal dilatation due to ureteral reflux and repeat ultrasound with an empty bladder should be carried out. Persistent or increasing hydronephrosis on repeat ultrasound examinations is highly suggestive of obstruction. Renal scan with furosemide washout may help support the diagnosis, but it does not provide anatomic details. Confirmation of the obstruction can be made by retrograde pyelogram but the ureteral orifice may be difficult to catheterize. Although invasive, percutaneous nephrostomy tube placement with antegrade nephrostogram is the most effective way to visualize the collecting system and can be of both diagnostic and therapeutic value.

Blood clots, technically poor reimplant, and ureteral sloughing are common causes of early acute obstruction after transplantation. Ureteral fibrosis secondary to either ischemia or rejection can cause intrinsic obstruction. The distal ureter close to the ureterovesical junction is particularly vulnerable to ischemic damage due to its remote location from the renal artery, hence compromised blood supply. Although uncommon, ureteral fibrosis associated with polyoma BK virus in the setting of renal transplantation has been well-described. Ureteral kinking, lymphocele, pelvic hematoma or abscess, and malignancy are potential causes of extrinsic obstruction. Calculi are uncommon causes of ureteral obstruction. Definitive treatment of ureteral obstruction due to ureteral strictures consists of either endourologic techniques or open surgery. Intrinsic ureteral scars can be treated effectively by endourologic techniques in an antegrade or retrograde approach. An indwelling stent may be placed to bypass the ureteral obstruction and removed cystoscopically after 2–6 weeks. An antegrade nephrostogram should be performed to confirm that the urinary tract is unobstructed prior to nephrostomy tube removal. Routine ureteral stent placement at the time of transplantation has been suggested to be associated with a lower incidence of early postoperative obstruction. Extrinsic strictures, strictures that are longer than 2 cm, or those that have failed endourologic incision, are less likely to be amenable to percutaneous techniques and are more likely to require surgical intervention. Obstructing calculi can be managed by endourologic techniques or by extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy.

UTI

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the most common bacterial infection in the paediatric population [4]. The incidence is initially higher in boys, affecting up to 20.3% of uncircumcised boys and 5% of girls at the age of 1. There is a gradual shift, with UTIs affecting 3% of prepubertal girls and 1% of prepubertal boys. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) have defined a recurrent UTI as two or more episodes of pyelonephritis, or one episode of pyelonephritis plus one or more episodes of cystitis, or three or more episodes of cystitis. Diagnostic investigations include urinalysis, which may require suprapubic bladder aspiration or bladder catheterisation in infants. A urine culture and microscopy should be carried out if there is evidence of infection. The role of further imaging is to differentiate between an uncomplicated and complicated UTI, but should also be considered in those with haematuria. A UTI is complicated in the presence of an abnormal urinary tract including upper tract dilatation, atrophic or duplex kidneys, ureterocoele, posterior urethral valves, intestinal connections, and vesico-ureteric reflux (VUR). NICE guidelines recommend an urgent ultrasound of the urinary tract for all those with recurrent UTI under six months. For children six months and older, NICE in the UK recommends an ultrasound within six weeks of the latest infective episode. All children with recurrent UTIs should be referred to a paediatric specialist and have a dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scan within four to six months of an acute infection to evaluate for renal scarring. European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines recommend a renal tract ultrasound in febrile UTIs if there is no clinical improvement, as an abnormal result is seen in 15% of these patients. Routinely repeating a urine culture in children treated with an antibiotic based on previous urine culture susceptibilities is not necessary [5]. Approximately 10%–30% of children develop at least one recurrent UTI, and the recurrence rate is highest within the first 3 to 6 months after a UTI. Renal scarring increases with an increasing number of febrile UTIs and with delayed treatment; therefore, parents should be counseled regarding the high risk of recurrent UTI and seek prompt evaluation for subsequent febrile illnesses in their child. Children who had a febrile UTI should routinely have their height, weight, and blood pressure monitored by their primary care provider. Children with significant bilateral renal scars or a reduction of renal function warrant long-term follow-up for the assessment of hypertension, renal function, and proteinuria.

Colic

Urolithiasis represents the commonest cause of acute ureteric colic, with calcium stones accounting for approximately 80% of cases [6]. Ureteric calculi have a prevalence of approximately 2–3% in Caucasian populations, with a lifetime risk of 10–12% in males and 5–6% in females. They are more common in developed countries, in men, in those with a positive family history, and in those with inadequate daily water intake. Ureteric colic typically presents with acute severe loin pain – which patients often describe as unrelenting despite a number of postural changes – and haematuria. Vomiting is often a feature of severe uncontrolled pain. Most patients with renal colic present because of severe uncontrolled pain and do not have signs of overt sepsis. Opiates are commonly given, although diclofenac sodium has been shown to be at least as effective for pain relief, particularly via rectal administration. Despite initial concerns, diclofenac sodium therapy has not been associated with renal toxicity in patients with preexisting normal renal function. Fever, tachycardia, tachypnoea and hypotension suggest sepsis secondary to an infected, obstructed kidney, which represents a life-threatening condition. Immediate management comprises prompt resuscitation, establishment of intravenous (IV) antibiotics, rapid diagnosis and decompression of the obstructed renal system, usually by ultrasound-guided percutaneous nephrostomy. Early involvement of urology and critical care services is essential in such patients. The management of ureteric calculi depends upon factors relating to the stone and the patient. Pre-eminent stone factors are size and site. It has been shown that 71–98% of stones <5 mm will pass spontaneously, whereas rates of spontaneous passage for stones >7 mm are low. Stone passage is also related to location in the ureter; 25% of proximal, 45% of mid and 75% of distal ureteric stones will pass spontaneously. In patients in whom stone passage is deemed likely, a trial of conservative management should be employed. Exceptions include patients with a functional or anatomical solitary kidney, bilateral ureteric obstruction, uncontrolled pain, or the presence of infection. Patients without contraindications should receive diclofenac sodium 50 mg tds, which has been shown to reduce the frequency of recurrent renal colic episodes. Recent evidence suggests that additional treatment with smooth muscle relaxants is associated with increased rates of stone passage over analgesics alone. A recent meta-analysis of studies using either nifedipine or tamsulosin, showed an approximate 65% greater chance of stone passage when such agents were used compared with equivalent controls. Intervention is generally reserved for large stones (>7 mm), conservative treatment failures and those with contraindications to a watchful waiting approach. Options include extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy and retrograde ureteroscopic stonefragmentation.

A stone can traverse the ureter without symptoms, but passage usually produces pain and bleeding [7]. The pain begins gradually, usually in the flank, but increases over the next 20–60 min to become so severe that narcotics may be needed for its control. The pain may remain in the flank or spread downward and anteriorly toward the ipsilateral loin, testis, or vulva. A stone in the portion of the ureter within the bladder wall causes frequency, urgency, and dysuria that may be confused with urinary tract infection. The vast majority of ureteral stones <0.5 cm in diameter pass spontaneously. Helical computed tomography (CT) scanning without radiocontrast enhancement is now the standard radiologic procedure for diagnosis of nephrolithiasis. The advantages of CT include detection of uric acid stones in addition to the traditional radiopaque stones, no exposure to the risk of radiocontrast agents, and possible diagnosis of other causes of abdominal pain in a patient suspected of having renal colic from stones. Ultrasound is not as sensitive as CT in detecting renal or ureteral stones. Standard abdominal x-rays may be used to monitor patients for formation and growth of kidney stones, as they are less expensive and provide less radiation exposure than CT scans. Calcium, cystine, and struvite stones are all radiopaque on standard x-rays, whereas uric acid stones are radiolucent.

Ureteral Stone Disease

Nephrolithiasis occurs with an estimated overall prevalence of 5.2% and there is evidence that stone disease is on the rise [8]. However, many stones in the kidney go undetected because they cause no symptoms or obstruction. Conversely, ureteral stones rarely remain silent, and they have greater potential for causing pain and obstruction. As such, ureteral stones that fail to pass spontaneously require surgical intervention. Although the introduction of medical expulsive therapy (MET, the use of pharmacological agents to promote spontaneous stone passage) has changed the natural history of ureteral stone disease, not all ureteral stones respond to MET. Indications for surgical intervention to remove ureteral calculi include stones that are unlikely or fail to pass spontaneously with or without MET, stones that cause unremitting pain regardless of the likelihood of spontaneous passage, stones associated with persistent, high-grade obstruction, stones in patients with an anatomically or functionally solitary kidney or in those with renal insufficiency or stones in patients for whom their occupation or circumstances mandate prompt resolution (i.e. pilots, frequent travelers, etc.). Once the decision has been made to intervene surgically for a patient with a ureteral stone, treatment options include shock-wave lithotripspy, ureteroscopy, percutaneous antegrade ureteroscopy and open or laparoscopic ureterolithotomy. Although special cirumstances may dictate the application of percutaneous antegrade ureteroscopy or ureterolithotomy (large, impacted stones, stones in patients with urinary diversions or stones that fail less invasive approaches), the two most widely practiced treatment modalities for ureteral stones are shock-wave lithotripsy (SWL) and ureteroscopy (URS). Both are associated with high success rates and low morbidity. However, the optimal treatment for ureteral stones remains controversial because of passionate advocates on both sides of the controversy. Proponents of SWL cite the noninvasiveness, high patient satisfaction and ease of treatment, while URS advocates favor the short operative times, high success rates and short time interval to become stone free.

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopic examination of urethra and bladder should be systematic [9]. The female urethra is only 2.5–4 cm long. Urethral mucosa should be examined for strictures, diverticular opening, or polyps, and the bladder neck is visualised as scope enters and exits the bladder. Base and trigone of the bladder are initially inspected. Trigone lies proximal to the bladder neck; it is the triangular area bounded by the inter-ureteric ridge and the bladder neck at the base of the bladder. One of the most common features of the trigone is squamous metaplasia, present in up to 50% of the women. It is a benign feature with no malignant potential. In staging for cervical cancer, when imaging suggests stage 3 or 4 disease, cystoscopy is indicated. The bladder base and trigone appearance such as bullous edema, inflammatory changes, or infiltration has to be documented, and in case of infiltration, biopsy should be part of the evaluation. Ureteric orifices are slit-like openings easily identifiable by the presence of efflux on either side of the inter-ureteric ridge. The ureteral orifices location, number, nature of ureteric efflux (clear, blood stained), and any anatomical distortion is noted. In a woman with anterior vaginal wall prolapse or an underlying cervical mass, identification of trigone or ureteric orifices may be difficult. In such cases, placing a finger inside the vagina and elevating the bladder base with a finger will be helpful. Blood stained ureteric efflux denotes upper tract pathology and further assessment of the ureter and kidneys is indicated, either by ultrasound or a CT scan of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder (CT KUB). In intra-operative or postoperative ureteral integrity assessment, presence of just ureteric peristalsis does not rule out ureteral injury. Checking for ureteric efflux after administration of methylthionium chloride or indigo carmine (5ml) IV is effective in confirming ureteral patency.

Injury

Most ureteral injuries are iatrogenic in the course of pelvic surgery [10]. Ureteral injury may occur during transurethral bladder or prostate resection or ureteral manipulation for stone or tumor. Ureteral injury is rarely a consequence of penetrating trauma. Unintentional ureteral ligation during operation on adjacent organs may be asymptomatic, though hydronephrosis and loss of renal function results. Ureteral division leads to extravasation and urinoma. If the ureteral injury is not recognized at surgery, the patient may complain of flank and lower abdominal pain on the injured side. Ileus and pyelonephritis may develop. Later, urine may drain through the wound (or through the vagina following transvaginal surgery) or there may be increased output through a surgical drain. Wound drainage may be evaluated by comparing creatinine levels found in the drainage fluid with serum levels; urine exhibits very high creatinine levels when compared with serum. Intravenous administration of 5 mL of indigo carmine causes the urine to appear blue-green; therefore, drainage from an ureterocutaneous fistula becomes blue, compared to serous drainage. Anuria following pelvic surgery not responding to intravenous fluids may rarely signify bilateral ureteral ligation or injury. Peritoneal signs may occur if urine leaks into the peritoneal cavity.

Conclusion

The ureter starts from the renal pelvis, descends down the retroperitoneal space of the abdominal cavity and enters the pelvis, where it ends by pouring into the urinary bladder. Therefore, it distinguishes the abdominal and pelvic part. The boundary between these parts is the so-called terminal line. When entering the pelvic cavity, the ureter forms a border curve and in this narrowed part the kidney stone can be stopped. The curvature of the ureter is projected on the anterior abdominal wall in the area of the Hale topographic point. Urinary tracts pass through the bladder wall obliquely. When the bladder wall is stretched, the fold of its mucosa acts as a valve and prevents the return of urine to the ureters and the possible spread of infection from the bladder to the kidneys.

For more Lupine Journals please click here: https://lupinepublishers.com/index.php

For more Journal of Urology & Nephrology Studies articles please click here: https://lupinepublishers.com/urology-nephrology-journal/index.php

#nephrology#lupine journals#open access journals#journal of urology & nephrology studies#nephritis#submission#articles#juns#lupine publishers#urology

0 notes

Text

Lupine Publishers | Radiology; USG and Colour Doppler of Post Renal Transplant Complications

Abstract

Kidney transplant is the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney transplant offers better quality of life. It is more cost effective than hemodialysis. Advances in surgical technique, along with improvement in organ preservation and immunosuppression have improved patient outcomes. Post-operative complications, however, can limit this success. Ultrasound and Doppler study is the primary imaging modality for evaluation of renal transplant, providing real –time information about complication in graft. A multimodality approach including CT scan, MRI or conventional angiography may be necessary in cases when sonography and Doppler are inconclusive to diagnose the etiologies of these complications. Radiologists play an integral role within the multidisciplinary team in care of transplant patient at every stage of the transplant process. Therefore, the radiologist should always be aware when evaluating the failing renal graft, whether the cause is renal or extrinsic. In this pictorial essay we tried to gather the most common complication of transplant kidney in different cases that occurred in our hospital, with an emphasis on Ultrasound and Doppler study.

Keywords: USG; Colour Doppler; Post renal transplantation; Complications

Introduction

The preferred modality for renal replacement is renal transplantation, and its superiority in prolonging the longevity of patients with end-stage renal disease is well established [1]. Kidney transplantation is typically classified as deceased-donor (formerly known as cadaveric) or living-donor transplantation depending on the source of the donor organ. Due to improvement in transplantation technology, advancement in immunosuppressant and graft preservation techniques the 1-year survival rates for grafts, are reported to be 80% for mismatched cadaveric renal grafts; 90% for nonidentical living related grafts; 95% for human lymphocyte antigen-identical grafts [2]. Radiologists play a major role at every stage of the transplant process with transplantation team. Ultrasonography with colour Doppler is the principal modality used for evaluation of renal allograft. USG is a relatively cheap, noninvasive, and non-nephrotoxic modality. It is applied for diagnostic and monitoring purposes in the post-transplant period. This pictorial essay describes USG and Doppler imaging appearances of the major complications that may occur in renal transplantation. All our images have been obtained from a single our center which is major transplantation center in India. All post renal transplant patients undergo a USG and comprehensive Doppler evaluation on post-operative day one. The sonographic examination algorithm includes gray-scale evaluation of the graft and spectral Doppler. Further imaging is based on clinical follow-up including daily monitoring of laboratory values. If clinical parameters are abnormal, repeat sonography is performed and depending on the results, CT, MRI, or angiography may be requested.

Surgical Technique

Surgical technique and location of placement of renal allograft depends on the variation in arterial and venous anatomy of donor. The transplanted kidney is usually placed extraperitoneally in the patient’s right iliac fossa (less commonly in left iliac fossa), with end-to-side or end to end anastomosis to the external iliac vasculature. The currently preferred method for restoring urinary drainage is ureteroneocystostomy, a procedure by which the ureter is implanted directly into the dome of the bladder (Figure 1).

Urologic Complications

The prevalence of urologic complications varied from 10% to 25% with a mortality rate ranging from 20% to 30%. Incidence rate is decreased range between 3% and 9% in the current era because of advancement in surgical techniques and frequent use of ureteral stents [3,4].

Urinary Obstruction

a) Incidence: 2%-5% of kidney transplant recipients.

b) Site of obstruction: Approx. 90% of stenoses occur in the distal third of the ureter due to its poor vascular supply.

c) Imaging appearance: US can easily confirm the diagnosis of hydronephrosis and dilated renal pelvis and thus determine the level of ureteral obstruction (Figure 2). When contents of pelvic calyceal system are echogenic and weakly shadowing, fungus balls should be considered, whereas low-level echoes suggest pyonephrosis (Figure 3).

Urine Leaks and Urinomas

a) Incidence: up to 6 % of renal transplant recipients [5]

b) Location: extraperitoneal or intraperitoneal, if intraperitoneal may present with ascites.

c) Imaging appearance: USG findings are nonspecific, well defined anechoic fluid collection with septa or without septation, adjacent to the lower pole of the transplant in most of the cases (Figure 4).

Drainage of fluid under ultrasound guidance and testing the fluid for creatinine helps to differentiate it from seromas or lymphoceles. High concentration of creatinine will be found in case of urinoma if we compare with serous fluid.

Calculous Disease

a) Incidence: 1% to 2 % of post-transplant cases develops clinically relevant stones as compared to general population [6]. As the kidney is denervated patient will not suffer typical renal colic.

b) Imaging appearance: Calculus appears as strongly reactive focus of variable size producing acoustic shadowing on USG and twinkling artifact on colour Doppler (Figure 5). Other rare urologic complications are ureteric necrosis and vesico-ureteric reflux.

Peritransplant Fluid Collections

Fluid collection in peritransplant region has been reported in up to 50 % of renal transplantation. They are urinomas, hematomas, lymphocele and abscess, the clinical relevance of these collection is largely determined by their size, location and possible growth. In immediate postoperative period, small hematomas or seroma are almost expected. Their size should be documented at baseline examination. Rarely do they lead to graft dysfunction or obstruction of collecting system. Urinomas and hematomas are most likely to develop immediately after transplantation, whereas lymphoceles generally develop after 4 to 8 weeks. The ultrasonography characteristics of peritransplant fluid collections, however, are entirely nonspecific, correlation with clinical findings helps to restrict differential diagnosis. Ultimately, diagnosis may be made only with percutaneous aspiration and then biochemical analysis. Differentiation between Peritransplant and subcapsular collection is important. A subcapsular collection likely to cause mass effect on parenchyma, usually cresenteric and show extension along the contour of kidney deep to the renal capsule

Hematoma

a. Incidence: Varies from 4 to 8 % [7]

b. Imaging appearance: Hematomas have a complex appearance. Hematomas appears echogenic in acute case and progressively become less echogenic with time (Figure 6). Chronic hematomas even appear anechoic, more closely resembling fluid and septation may develop later on.

Lymphocele

a. Incidence: Affecting up to 20% of the patients [8] It occurs after surgery owing to the surgical disruption of the normal lymphatic channels along the iliac vessels or around the hilum of the graft.

b. Imaging appearance: on Ultrasound it appears as anechoic bur may contain septation. They may become infected and gave more complex appearance (Figure 7).

Peritransplant abscesses

a) Imaging appearance: USG cannot always differentiate an abscess from other collection. Collection may show low level echoes and thick irregular wall. If gas is seen, an abscess is probable. In any pyrexia patient, any perinephric collection should be considered infected until proven otherwise through the appropriate imaging and guided diagnostic aspiration.

Parenchymal Complication / Graft Dysfunction

Diseases of the renal parenchyma are usually diffuse and often leads graft dysfunction. Differential diagnosis is difficult by imaging alone. USG is not sensitive or specific for evaluation; differential will be relying on biopsy. USG still has a central role in qualitative assessment of graft perfusion and to guide the biopsy.

Acute tubular necrosis (ATN)

Acute tubular necrosis is due to reversible ischemic damage to the renal tubular cells prior to engrafting and reperfusion injury.

i. Incidence: affects 20–60 % of cadaveric renal grafts.

ii. Time of onset: in the first 48 hours after transplantation.

iii. Imaging appearance: No specific imaging pattern for the diagnosis of ATN. The kidney may appear normal, in severe cases it looks enlarged, edematous and echo poor with loss of corticomedullary differentiation (Figure 8) and shows elevated RI (above 0.8).

Rejection

Rejection can be classified according to the period of appearance as hyper acute (occurring within minutes), acute (occurring within days to weeks), late acute (occurring after 3 months), or chronic (occurring months to years after transplantation). Classification of renal allograft rejection by Banff classification of allograft pathology is routinely followed nowadays. It is based on a combination of histopathologic features coupled with molecular, serologic, and clinical parameters.

Acute Rejection (AR)

i. Incidence: up to 40% of patients in the early transplant period [9].

ii. Imaging appearance: Graft enlargement due to edema, Decreased cortical echogenicity, swelling of the medullary pyramids, echogenic sinus fat, edematous wall of pelvic calyceal system, focal hypoechoic areas in parenchyma which may favors infarct and collection in perigraft region due to necrosis or hemorrhage. PI and RI elevated in both ATN as well as in AR, but AR has high values of it. In severe cases, Power Doppler shows reduced, absent or reversed diastolic flow with elevation of the RI (Figure 9).

Chronic Rejection

Chronic rejection occurs in case of insufficient immunosuppression given to recipient to control the residual antigraft lymphocytes and antibodies.

i. Imaging appearance: US appearance is not typical, ranging from normal to hyper echogenic, along with cortical thinning, reduced number of intrarenal vessels, and mild hydronephrosis (Figure 10). RI measurements are not reliable for this diagnosis. The diagnosis is made histologically.

Drug Nephrotoxicity

Calcineurin inhibitors are key immunosuppression agents administered to avoid acute rejection, but they are nephrotoxic.

A. Imaging appearance: USG may show completely normal results or nonspecific findings such as graft swelling, increased or decreased renal echogenicity and loss of cortico-medullary differentiation. Doppler study may show a RI increase of 0.80. Findings of USG and Doppler study should be correlated with the serum drug levels. USG and Doppler findings of ATN and AR is almost similar, but both can be differentiated by time course of the findings. Clinical & biochemical correlation and serial measurements of RI and Pulsatile index (PI) would be further helpful to monitor the patient.

Infections and abscesses

Incidence and time of onset: More than 80% of renal transplant recipients have at least 1 episode of infection during the first year of post transplantation.

I. Imaging appearance: USG appearance is quite variable. Focal pyelonephritis appear as a focal hyperechoic or hypoechoic area, but this finding is nonspecific because it can represent infarction or rejection also (Figure 11). Abscess has varied appearance on USG like- heterogeneous, hypoechoic or cystic. Urothelial thickening may be seen. In febrile post renal transplant patient low level echoes in dilated collecting system may favors pyonephrosis. Fungus ball appears as focal rounded, weakly shadowing or echogenic structure in dilated pelvic calyceal system. In emphysematous pyelonephritis, gas in the parenchyma of the renal graft produces an echogenic line with distal reverberation artifacts. Papillary necrosis has no typical sonographic findings, and it subsequently leads to ureteric obstruction.

End stage disease

Nonfunctional renal grafts are left in place in abdominal cavity. Gradually graft becomes small and can have fatty replacement, hydronephrosis, infarcts, hemorrhage or calcification.

Vascular Complications

Vascular complications in post renal transplantation have significant negative influence of graft survival. They are infrequent, occur in approximately 1%–2%; [10] but can cause sudden loss of renal allograft. Selective catheter angiography is the gold standard for diagnosis; however, it is invasive and may cause various complications. Hence it is not used as a screening tool but reserved for patients with inconclusive results on the noninvasive screening tests. Noninvasive imaging like ultrasound, Doppler, scintigraphy, CT and MR angiography plays major role to evaluate them.

Renal artery thrombosis (RAT)

Incidence: Ranges from 0.5% to 3.5 % [11]

Imaging appearance: No evidence of any arterial or venous flow noted on color, spectral and power Doppler study (Figure 12). Doppler sonography had 100% sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis and hardly any other imaging study is required for diagnosis [12].

Focal Renal Infarction

Imaging appearance: A segmental infarct appears as a poorly marginated wedge shaped hypoechoic mass or a hypoechoic mass with a well-defined echogenic wall without colour flow (Figure 13). If the infarction is global, the kidney will appear hypoechoic and be diffusely enlarged.

Renal Artery Stenosis (RAS)

Incidence: It has wide range varying from 1% to 23 % depending on the definition and diagnostic techniques used.

Site: usually at anastomotic site

Imaging appearance: On gray scale USG, there is lack of normal post-transplant hypertrophy. On color Doppler study appearance of focal color aliasing noted at stenotic segments. On spectral Doppler study, peak systolic velocity in main renal artery >300 cm/sec and Ratio of PSV in transplanted main renal artery and external iliac artery greater than or equal to 1.8 are highly suggestive of significant stenosis. Indirect criteria are low resistive index <0.56, Acceleration time >0.07 sec, Acceleration index <3 meter/ sec and Intrarenal tardus–parvus waveform (Figure 14).

Limitation: Results are strongly depends on the operator’s individual experience and skill.

Rate of restenosis is less than 10 %. Doppler ultrasonography is the procedure of choice to evaluate graft perfusion before and after revascularization The term pseudo transplant renal artery stenosis (TRAS) refers to thrombosis or stenosis of iliac artery or aorta proximal to transplant renal artery.

Renal vein thrombosis: (RVT)

Incidence: Ranges from 0.9% to 4.5 % [13]

Imaging Findings: Graft appears swollen and hypoechoic.

Doppler shows absent venous flow. Renal arterial Doppler spectrum shows absent or reversal of diastolic flow due to increased resistance (Figure 15). Reversal flow in renal artery is nonspecific as it also seen in severe rejection and in acute tubular necrosis, its combination with absent venous flow is the diagnosis of renal vein thrombosis. Partial thrombosis also can occur near anastomosis or within the transplanted kidney (Figure 16).

Extra parenchymal pseudo aneurysm

Incidence: Anastomotic pseudoaneurysm is a rare complication of renal transplantation occurring in 0.3%. [14]

Imaging findings : On gray scale ultrasound it appears as cystic lesion which shows color flow and to and fro spectral pattern on doppler study(Figure 17). Endovascular treatment with covered stent placement to exclude pseudoaneurysm can also be evaluated with USG and colour doppler (Figure 18).

Intra-parenchymal arteriovenous fistula and pseudoaneurysm

AVF occurs when both artery and vein are simultaneously lacerated, while pseudoaneurysm results when only artery is lacerated.

Incidence: 1-18% of the biopsies [15]

Time of onset: occur at time of biopsy. They depend on many factors – ultrasound guidance, needle caliber and imaging follow up.

Imaging appearance: colour Doppler study shows AVF as focal areas of disorganized flow adjoining the normal vasculature. Spectral waveforms show increased arterial and venous flow with high velocity and low resistance (Figure 19). Pseudoaneurysm appears as simple or complex cyst on B mode ultrasound and intracystic flow on colour Doppler mode (Figure 20).

Neoplasms after renal transplantation

Post renal transplantation patients are at higher risk of development of neoplasms. Urologic tumour are 4 to 5 times more common in post renal transplantation recipients than normal population with significant exposure to cyclophosphamide immunosuppressant agent.

Renal cell carcinoma

Etiology: by means of transplanted organ or de novo development by immunocompromised status, patients on hemodialysis in case of chronic renal failure develop acquire renal cystic disease

Prevalence: 90 % occurring in native kidney and 10 % in transplanted kidney [16]

Imaging appearance: lesion appear heterogeneous with vascularity, similar picture as seen in native kidney [17] (Figure 21).

Lymphomas

Incidence: 1 % of renal allograft recipients [18]

Time of onset: Post transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder is diagnosed at a median of 80 months after transplantation.

Imaging appearance: Lymphadenopathy at various sites but can also affect any solid organ or hollow viscera or transplant graft parenchyma itself. It appears as low or mixed reactive masses and tends to have a predilection for the renal hilum.

Recurrent Native disease

It depends on the primary disease before transplantation.

Imaging appearance: Imaging has no specific pattern in these situations apart from excluding the treatable cause of reduced renal function.

Abdominopelvic Complications

Renal graft is placed in extraperitoneal space via a peritoneal window in laparoscopic and robot assisted surgical techniques. So these cases are prone to same complications experienced by other surgical cases in whom peritoneum is exposed.

Renal Allograft Compartment Syndrome (RACS)

It is a rare syndrome, and it is under recognized cause of early transplant dysfunction or even loss. It may occur as a result of intracompartment hypertension and ensuring ischemia of renal graft [19]. Imaging appearance: absent or diffuse diminished cortical flow in transplant kidney at colour Doppler.

Fascial dehiscence and bowel or allograft evisceration

They tend to occur in perioperative period. Herniation of bowel through a transplant peritoneal defect may lead to compromise of intestine or transplant itself.

Limitations

The USG examination is examiner dependent and limited accessibility in obese patents impairs the evaluation and often leads misinterpretation. The RI index is also unspecific and influenced by many factors like site at which the RI is measures, increased intraabdominal pressure during forced inspiration and the pulse rate.

Summary

Kidney transplant is the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage renal disease. Improvements in surgical techniques and advanced immunosuppressive drugs have resulted in remarkable survival of patients and renal grafts. Still complications occur in both the early postoperative period and later. Kidney transplants follow up is common in radiology and sonography practice.

Ultrasonography and Doppler examination can accurately depict and characterize many of the potential complications of renal transplantation. It facilitates prompt and accurate diagnosis and thus guiding treatment.

For more Lupine Journals please click here: https://lupinepublishers.com/index.php

For more Journal of Urology & Nephrology Studies articles please click here: https://lupinepublishers.com/urology-nephrology-journal/index.php

#lupine publishers#open access journals#urology#nephrology#submission#journal of urology & nephrology studies#juns#lupine journals#nephritis#articles

0 notes

Text

Lupine Publishers | Evaluation of Buccal Mucosal Graft Urethroplasty for The Treatment of Female Urethral Strictures- A Single Centre Experience

Abstract

Introduction: Female urethral stricture is a highly under-reported and underdiagnosed condition encountered by the reconstructive urologist. Urethral dilatation is often performed with urethroplasty offered in select cases. In the present study, we describe our results in a series of women surgically treated for female urethral stricture disease using a suprameatal approach with a buccal mucosal graft dorsal on lay technique. Materials and Methods: All females diagnosed of urethral stricture who underwent buccal mucosal graft urethroplasty from January 2015 to January 2020 were evaluated retrospectively. Intraoperative and postoperative parameters were assessed. Results: A total of 14 female patients underwent buccal mucosal urethroplasty were evaluated. The mean age of the patients was 49.5 years ranging from 35 to 64 years. Mean preoperative maximum flow rate [Qmax] on uroflometry was 6.5 ml/second and the mean residual urine 156 ml. All patients underwent uneventful buccal mucosal graft dorsal on lay technique. At 3 months follow up, the mean Qmax was 23.2 ml/second with mean residual urine of 14 ml. A Self-reporting satisfaction scores using the Patient Global Impression of Improvement showed that seven patients scored 1 (very much better), four scored 2 (much better), two patients scored 3 (a little better), and one scored 4 (no change) none of the patients scored a 5 (worse).No recurrence was noted. Conclusion: Buccal mucosal graft urethroplasty is a feasible surgery for female urethral strictures with minimal short term complications

Keywords: Buccal Mucosal Graft Urethroplasty; Female Urethral Strictures

Introduction

Female urethral stricture is a highly under-reported and underdiagnosed condition encountered by the reconstructive urologist. The aetiology of urethral stricture is still unclear. Symptoms range from clinically insignificant to severe and debilitating voiding symptoms. Urethral dilatation has been overused for primary and chronic treatment. Urethroplasty with various grafts and flaps have been used with good results in recent times. In this present study, we describe our results in a series of women surgically treated for female urethral stricture disease using a suprameatal approach with a buccal mucosal graft dorsal on lay technique.

Patients and Methods

A total of 14 female patients with urethral stricture who underwent buccal mucosal graft urethroplasty from January 2015 to January 2020 were evaluated retrospectively. Patients were evaluated with a detailed history, physical examination including focused neurological evaluation, uroflometry, a micturating cystourethrogram and an ultrasound of abdomen and pelvis. Evaluation also included a gentle calibration of urethra with a 14 French catheter to assess the site of stricture. All patients had a history of poor stream of urine, 10 (71%) had a sense of incomplete voiding, 2 (14%) presented with recurrent urinary tract infection and 2 (14%) patients had terminal dribbling. Aetiology of the stricture was idiopathic in 9 (64%) of the patients, instrumentation in 3 (22%) and catheterization in 2 (14%). More than half, that is 8 (57%) of the patients had history of repeated urethral dilatation.

Surgical technique

Routine preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis was given and under general anaesthesia with nasal intubation, the surgery was performed in lithotomy position. An initial Urethroscopy was performed with a 6 French ureteroscope to assess the site of stricture, the proximity of the stricture to the bladder neck and any abnormalities in the bladder and trigone. A diluted mixture of 2% xylocaine and adrenaline was injected submucosally into the periurethral tissue using a 26 gauge needle for hydro dissection and haemostasis. An inverted ‘U’ shaped incision (Figure 1A) was given over the urethra exposing the dorsal part of the urethra. Sharp dissection was then done in order to separate the vulvar mucosa from the urethra (Figure 1B). Utmost care was taken to prevent damage to the clitoral cavernous tissue and the anterior portion of the striate sphincter. A full thickness urethrotomy was made using tenotomy scissors at 12 ‘O’ clock position over a guide wire and then extended proximally till normal healthy mucosa could be visualised. The urethra was then calibrated with 18 French catheter to rule out proximal stricture.

The buccal mucosal graft was then harvested. The Stenson’s duct was marked opposite the upper second molar tooth. Methylene blue was used to mark the graft area to be harvested. A diluted mixture of 2% xylocaine and adrenaline was injected submucosally using a 26 gauge needle for hydrodissection and hemostasis. The buccal mucosal graft was harvested based on the length of the stricture. Haemostasis was achieved with bipolar cautery and the raw area was packed with adrenaline soaked gauze. Buccal mucosa was allowed to heal by secondary intention. Defatting of the graft was performed and the graft was placed in a container with gentamycin and saline. An 18 French catheter was then introduced into the urethra and bulb was inflated. The buccal graft was then sutured to the apex at 11, 12 and 1 ‘0’ clock position (Figure 1C). The lateral margins of the urethra and buccal mucosa were sutured in a dorsal on lay fashion with 4-0 vicryl suture (Figure 1D). This augmented urethra was then quilted to the clitoral body to cover the new urethral roof (Figure 1E). Vulvar mucosa was then approximated with 4-0 vicryl suture. Patients were discharged with catheter after 2 days and were called for catheter removal after 3 weeks (Figures 2A-2D). Patients were followed up after 3 months with assessment of voiding symptoms, examination (Figure 3), uroflometry and a micturating cystourethrogram. The criteria of successful reconstruction were defined as postoperative maximum flow rate (Qmax) greater than 15ml/sec with minimal post void residue (<10% of pre-void). A Self-reporting satisfaction scores using the Patient Global Impression of Improvement was used for assessment of urinary symptoms at 3 months follow up. At subsequent follow ups, the patients were assessed with voiding symptoms and an uroflometry.

Results

A total of 14 female patients underwent buccal mucosal urethroplasty from January 2015 to January 2020. The mean age of the patients was 49.5 years ranging from 35 to 64 years. Mean preoperative maximum flow rate [Qmax] on uroflometry was 6.5ml/ second ranging from 4 to 7.2ml/second (Table 1). The mean residual urine was 156 ml. In all the patients, calibration with 14 Fr catheter was not possible preoperatively. The mean operative time was 96 minutes ranging from 84 minutes to 116 minutes. Mean stricture length was 1.4 centimetres ranging from 1 to 2.2 centimetres. The mean length of the harvested graft was 2.5 cms ranging from 2.0 to 3.5 cms. Our mean follows up period was 22 months ranging from 6 months to 45 months. None of the patients developed any evidence of graft necrosis post operatively. No wound infection was noted in our series. No donor site complication was noted in our series. Mean hospital stay was 2.5 days ranging from 2-4 days. At 3 months follow up, the mean Qmax was 23.2 ml/second with mean residual urine of 14ml. A Self-reporting satisfaction scores using the Patient Global Impression of Improvement was used which showed that that seven patients scored 1 (very much better), four scored 2 (much better), two patients scored 3 (a little better), and one scored 4 (no change) none of the patients scored a 5 (worse) (Table 2). None of the patients developed recurrence, incontinence, or sexual dysfunction during the course of our follow up.

Discussion

Female urethral stricture has been described for almost 200 years but is still a widely underdiagnosed condition [1]. Brannen described the history of female urethral stricture and said that it was first described by Liz Frank in 1824 and the first case of female urethral stricture was reported to the earl of London in 1828 [2]. The exact incidence of this entity remains unknown with very few case reports and retrospective case series reported in contemporary literature till date [3]. The aetiology for female urethral stricture has been attributed to idiopathic (49%), chronic irritation, Prior dilatation, catheterization, instrumentation (7%) and trauma (6%) [4-7]. Trauma may be in the form of obstetric injuries, blunt pelvic trauma, or even repeated vigorous coitus [2]. In our study, idiopathic stricture was the most common cause accounting for 64% of the cases. Patients usually present with long standing complaints of voiding and storage symptoms, recurrent urinary tract infections and sometimes upper urinary tract changes. Irritative voiding symptoms may be the presenting complaint in 35% of the patients [8]. Evaluation of the patients include a detailed history including history of stress and urge incontinence, local examination of the meatus, uroflometry and measurement of residual urine. Examination should also include gentle calibration with a 14 French catheter [9]. Radiological evaluation of the stricture with a micturating cystourethrogram helps visualise the stricture. Options for management of these strictures include urethral dilatation, urethroplasty with grafts (oral/vaginal) or flaps (vaginal/labial) [4]. Urethral dilatation alone has a dismal success rate of 47% at a mean follow up of 43 months [4]. The mean time to recurrence of stricture has been reported to be around 12 months [10]. Dilatation combined with daily intermittent self-catheterization is said to have a success rate of 57% [10,11]. Like in males, it appears that, if a single dilatation fails, then it is probable that further dilatations are likely to be palliative rather than curative [4]. Urethral reconstruction in women is different from that of men because of the shorter length of the urethra and that the female urethra is sphincter active. Hence any urethral surgery in the female carries a substantial risk of incontinence. Anastamotic urethroplasty has not been described till date. The various approaches to urethral reconstruction are ventral approach or a dorsal approach. We preferred the dorsal approach because of the good mechanical and vascular support provided by the clitoral and cavernosal tissue, it prevents the downward angulation of the urethral meatus, which may have a subsequent impact on the direction of the urinary stream and further, it spares the ventral aspect of urethra for further anti-incontinence surgery. The disadvantages being increased chances injury to the sphincter and neurovascular bundle which may lead to in continence or sexual dysfunction. A total of 15 studies with 115 patients described urethroplasty for female urethral strictures, with 6 studies describing flaps and 10 studies describing the use of free grafts for urethral augmentation [4]. A total of 6 studies have described the use of oral grafts for female urethral strictures [12-17]. The individual success rate with the use of oral mucosal graft was 94% with a mean follow up of 15 months [4]. There were no reported incidences of de novo incontinence. Oral mucosa is particularly helpful when vaginal atrophy and fibrosis precludes the use of a local flap. In our series, there were no cases with recurrence and none of the patients complained of urinary incontinence post op. With the use of vaginal or labial grafts, the success rate was reported to be around 80% at a mean follow up of 22 months [4]. Successful outcome with the use of vaginal flaps is reported to be around 91% at 32 month follow up. The main drawbacks of this study are the retrospective nature of study, lack of control group and short term follow up. A randomized study with a control group and long term follow up is needed to further validate this procedure.

Conclusion

Buccal mucosal graft urethroplasty is a feasible surgery for female urethral strictures with minimal short term complications.

For more Lupine Journals please click here: https://lupinepublishers.com/index.php

For more Journal of Urology & Nephrology Studies articles please click here: https://lupinepublishers.com/urology-nephrology-journal/index.php

#lupine journals#urology#nephrology#juns#journal of urology & nephrology studies#open access journals#articles#submission#research#review#casereports

0 notes

Text

Lupine Publishers | Safety and Efficacy Assessment of Pcnl in The Pediatric Population: A Single Centre Experience

Abstract

Introduction and Objective: Renal stone disease in children is on the rise with increased incidence and better modalities to diagnose the disease. Hence there is a necessity to strategize the evaluation and treatment of children with kidney stones. Our study was conducted to assess stone distribution, stone burden, and efficacy of PCNL in pediatric age group. Methods: All paediatric patients with renal stone disease who subsequently underwent PCNL at our department from January 2017 to December 2020 were analysed. Results: 84 patients ranging 1-18 years were analysed. Pain abdomen was the most common presenting symptom (61.9%) followed by fever (19.04%). The mean stone size was 2.16cm with equal side distribution. Most stones were located in the lower calyx (38%). The mean operative time was 65 minutes. Exposure to radiation from C arm ranged from 1.6-8.3 minutes. Complete stone clearance was achieved in 90.47% with a mean post- drop in Hb value to 0.72 gm/dl. Mean duration of nephrostomy tube in situ was 2.4 days and with a mean hospital stay of 3.8 days. Calcium oxalate was the most common type of stone (48%) Conclusion: PCNL is safe and effective treatment for pediatric renal calculi with minimal morbidity and increased stone free rates irrespective of stone size. Proper patient selection, surgical skill and postoperative care contribute towards the success of the procedure

Keywords: Pediatric PCNL; Pediatric Renal Calculi; Renal Stone Disease

Introduction

The prevalence of renal stone disease in children ranges from 5 to 15%. Stone disease has a higher risk of recurrence in the pediatric age group making it crucial to identify the most effective method for complete stone removal to prevent recurrence from residual fragments. The optimal management of for pediatric stone disease is still evolving [1,2]. Currently, ESWL is the procedure of choice for treating most upper urinary tract calculi in the pediatric population. However, a higher incidence of metabolic and anatomical abnormalities in pediatric patients has led to increased recurrence. Moreover, ESWL has relatively less efficacy for stones >1.5cm. Surgical intervention should be preferred in such cases so as to minimize the need for retreatment [3-5]. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) is less invasive than open surgery which can be a good candidate for complex and large burden stones [6]. Several studies over time with different power and limitations have reported safety and efficacy of PCNL leading to its consideration as the treatment of choice for children with stone larger than 15mm [7-9]. The advent of newer, finer instruments and increase in experience of endourological techniques such as tubeless PCNL, mini-perc, ultra-mini perc and micro-perc has resulted in reducing the morbidity rate among patients without affecting the outcomes in terms of clearance [10-14]. Therefore, our study was conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of PCNL in the pediatric age group in terms of (1) renal stone distribution & stone burden (2) the outcomes of PCNL including stone clearance, operative time, hospital stay, haemoglobin changes and (3) the associated complications of PCNL.

Materials and Methods

A prospective study was conducted at our hospital from January 2017 to December 2020 after obtaining institutional ethical committee clearance. All pediatric patients posted for PCNL at MS Ramaiah Medical College were considered in the study. The patients compatible for the study were interviewed and after obtaining informed and written consent they were enrolled in the study. Inclusion Criteria: All the patients below the age of 18 years undergoing PCNL. Exclusion Criteria: Anatomic abnormalities of the kidney (horseshoe kidney/malrotated kidney); Bleeding disorders; deranged renal function. Patients were initially evaluated with a detailed medical history and a thorough clinical examination followed by a battery of investigations including CBC, RFT, Serum electrolytes, serum levels of calcium, phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, uric acid, total protein, carbonate, albumin, parathyroid hormone (if there is hypercalcaemia), blood group & Rh typing, HbsAg, HIV, HCV, Urine: Routine & Microscopy, Urine: Culture & Sensitivity. For imaging –ultrasonography was used as a first study followed by spiral CT KUB if no stone was found. Intravenous pyelography was performed when a need arose to delineate the calyceal anatomy prior to percutaneous or open surgery. A sterile urine culture was confirmed before surgery. In patients with evidence of infection, antibiotics were given preoperatively to clear the infection prior to surgery. All patients received broad-spectrum antibiotics beginning 12 h prior to the procedure and these were continued until 5 days postoperatively. All PCNL are performed under general anaesthesia. The patient initially placed in lithotomy position and a ureteric access catheter was placed under fluoroscopic guidance. The patient was then turned prone. After initial puncture, the tract was dilated using metallic or Teflon dilators. Paediatric PCNL was performed using adult instruments and clearance assessed intraopeartively by fluoroscopy. Ureteric stents and nephrostomy tubes were placed in most patients at the end of the procedure. Baseline patient characteristics, intraoperative and post-operative data were collected and analysed. Perioperative complications were classified using the modified Clavien Dindo system. In case of a supra-costal puncture, a chest X-ray was obtained subsequently in the post op period. An x ray of kidney ureter bladder was taken at 48 hours after PCNL. If needed a re-look procedure was done. The patient was followed up with an ultrasound & serum creatinine at 3 months, DMSA scan after 6 months to know the functional status of kidney & amount of renal scarring. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22. Categorical variables were presented as number and percentage (%), whereas continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and median (Table 1).

Results

84 patients ranging between 1-18 years of age were analysed with the mean age of study population of 11.04 years. Pain abdomen was the most common presenting symptom (61.9%) followed by fever (19.04%) with 4/84 having had prior surgical intervention for stone disease (Figure 1). The mean stone size was 2.16cm with equal side distribution. Most stones were located in the lower calyx (38%) followed by renal pelvis – 33%, middle calyx 17% and upper calyx 12% (Figure 2a). The total operative time ranged from 30 minutes to 120 minutes with a mean of 65 minutes. Exposure to radiation from C arm ranged from 1.6-8.3 minutes. Intraoperative location of stone, puncture and after clearance are shown in Figures 1a,1b,1c. Complete stone clearance was achieved in 90.47% with a mean post- drop in Hb value to 0.72 gm/dl. Mean duration of nephrostomy tube in situ was 2.4 days and with a mean hospital stay of 3.8 days. Intra-operative and post-operative complications in the study population are depicted in Table 2. Calcium oxalate was the most common type of stone (48%) (Figure 3).

Discussion

Although short wave lithotripsy (SWL) is considered the treatment of choice for symptomatic upper urinary tract calculi in children, but not a preferred option in patients with large stone burden, owing to higher rates of failure and residual stones. In such cases, PCNL with proven advantages can be safely advocated as a suitable treatment option in order to avoid numerous SWL sessions under anesthesia. Despite pediatric PCNL being described as early as 1985 by Woodside et al. [6], pediatric surgeons had their reservation in performing PCNL in children. This apprehension was due to the fear of parenchymal damage, early exposure to radiation and risk of major complications associated with the surgery. However, Dawaba et al. [9] proved the fear to be baseless by demonstrating that PCNL in paediatric population improved overall renal function without causing renal scarring. Similarly, Mor et al. reported no significant scarring or loss of renal function in radionuclide renal scans (19). He concluded that adult type tract dilation to 24Fr to 26Fr was not associated with significant renal function loss [19]. The size, number and site of tracts are not well defined in pediatric PCNL. While Gunes et al. reported a higher complication rate in children <7 years operated with adult sized instruments [17], Desai et al. observed that intraoperative bleeding during PCNL in children is related to the size and number of tracts and suggested the need for technical modifications in children [20]. Although this calls for reduction in tract size, it may have an effect on the clearance rates. In our study, 54(64.28%) underwent standard PCNL vs 30(35.71%) underwent Miniperc. We used amplatz sheath sizes in the range of 16F-28F. Size of tract dilatation was based on dilatation of pelvicalyceal system, the stone burden and no of punctures. Our clearance rates & transfusion rates were found to be similar in miniperc & standard PCNL. Our results are in concurrence with Bilen et al. who reported that smaller tracts did not significantly affect stone-free rates but achieved lower transfusion rates [21]. They concluded that a 20Fr tract was as effective as working with adult sized devices and did not significantly increase the operative time. (18) Provided the quality of the puncture and subsequent tract is high, there is no greater morbidity than that reported from miniperc. Large tracts and instruments can facilitate more rapid and complete stone clearance (Table 3).

Most of the stone burden was located in lower calyx (38%) in most of our cases with staghorn calculus noted in 4 patients. Single tract access was done in 72 patients with lower calyceal puncture being used mostly (43%) (Figure 2b). Multiple punctures were required in 12 cases (14.2%). We did not find any significant increase in complications following an upper calyceal puncture or with multiple punctures in our study which is comparable to Sedat Oner et al. who concluded that an upper pole approach did not prolong operative time or add to the complications, making it a good alternative. A surgeon who has reached competence at performing PCNL should therefore not hesitate to use a superior caliceal approach in pediatric patients if deemed appropriate for stone removal [22]. Our length of hospital stay duration of nephrostomy tube in situ is comparable to previously published data. 42.85% of our cases were tubeless, which is safe when performing uncomplicated PCNL [34]. Prior renal surgery on the same side didn’t have any impact on outcome of PCNL [35]. Aldaqadossi et al. have suggested that a previous open pyelolithotomy or nephrolithotomy does not affect the efficacy and morbidity of subsequent PCNL in pediatric patients [35]. We achieved a complete clearance rate of 90.47% which is similar to the published literature. Residual calculi noted in 8 cases were managed by ESWL. The complication rate during and after PCNL in paediatric patients varies widely in the literature. The difference in complication rates may be explained by the difference in stone burden location and experience of the surgical team. Our complication rate was 9.52% with fever being the most common. The lower incidence in complications could be attributed to the surgeon expertise at our center.

Limitations

Our study population was from single referral center, which may not be generalizable considering small sample size. Another limitation is the lack of comparative groups such as ESWL/RIRS while evaluating the efficacy of PCNL.

Conclusion

PCNL is safe and effective treatment for pediatric renal calculi with minimal morbidity and increased stone free rates irrespective of stone size. Proper patient selection, surgical skill and postoperative care contribute towards the success of the procedure and reduces the complications.

For more Lupine Journals please click here: https://lupinepublishers.com/index.php

For more Journal of Urology & Nephrology Studies articles please click here: https://lupinepublishers.com/urology-nephrology-journal/index.php