Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Is the #Me too movement making progress in China?

picture source:https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/10/11/how-social-media-users-have-discussed-sexual-harassment-since-metoo-went-viral/

With Canadian-born star Kris Wu in criminal detention for alleged sexual assault, Alibaba has also been exposed in a sexual assault scandal. As related incidents continue to come to light, women's rights have become a hot topic of discussion among Chinese netizens. At the same time, more and more women are coming forward to fight for their legal rights. This means that the #Me too movement, and indeed the feminist movement, is leading the way for women to change their consciousness and make considerable progress in China.

Earlier, in 2017, the #Me too hashtag appeared on Twitter and began to spread. It became popular on 15 October of the same year, when actress Alyssa Milano took to Twitter to share the story of Hollywood executive Harvey Weinstein after accusing him of inappropriate behaviour. The article had a huge impact on the internet, with more and more people coming forward and telling their stories (Clark-Parsons, 2019).

The #Me too campaign is an empathy-based movement that aims to reach out to all victims of sexual harassment, especially women. The campaign focuses on the voices of the victims of incidents so that society can provide assistance in all areas. Over time, although similar incidents have not been fully resolved, the campaign has given a voice to women from different walks of life instead of just being silent.

In 2021 a user on Weibo named Meizhu Du posted an article accusing Canadian-born star Kris Wu of alleged sexual assault, which caused a heated debate on social media after it was posted. As the story continued to fester, netizens took to different social media platforms to encourage victims to come forward with their allegations. In response, Lin & Yang (2019) said that it was through social media that more people were able to speak out. However, as the incident came to light, it also exposed the long-standing problem of control over women in China's patriarchal society to the public eye. The fact that more and more women have come forward to speak out in this case is a major victory for the #Me too movement in China.

In the early days, however, feminist activism was monitored by the powers that be, and when victims posted messages on social media platforms, they were almost immediately deleted. Netizens saw this approach by women as having ulterior motives and even believed they would benefit from it. In recent years, the feminist movement in China has been the subject of a crackdown and some feminist accounts have gradually disappeared from social media platforms. As the government has introduced relevant regulatory policies, it has also, to some extent, sought to control the excessive attention given to related events on the internet. For example, Free Chinese Feminist, an organisation that focuses on the feminist movement in China, tweeted that "the independent media platform for women workers, Pepper Tribe, has announced its closure". I believe that the existence of this phenomenon may also be the result of a government crackdown.

picture source:https://www.voachinese.com/a/from-Kris-Wu-to-Alibaba-is-China-MeToo-movement-really-making-progress-20210816/6004161.html

In response, researcher Yaqiu Wang says the biggest impact of this movement is that more women are able to be brave enough to stand up and speak out, so that women's solidarity can be seen on the internet. Feminist awareness is growing, and the emergence of this event is proof that Chinese women are increasingly brave enough to stand up for themselves and fight for their rights.

Reference

Chunshan, M. (2018, July 31). China’s Sudden #MeToo Movement. Thediplomat.com. https://thediplomat.com/2018/07/chinas-sudden-metoo-movement/

Clark-Parsons, R. (2019). “I SEE YOU, I BELIEVE YOU, I STAND WITH YOU”: #MeToo and the performance of networked feminist visibility. Feminist Media Studies, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2019.1628797

从吴亦凡到阿里巴巴, “我也是”与女权运动在中国取得进步? (2021, August 16). 美国之音. https://www.voachinese.com/a/from-Kris-Wu-to-Alibaba-is-China-MeToo-movement-really-making-progress-20210816/6004161.html

Lin, Z., & Yang, L. (2019). Individual and collective empowerment: Women’s voices in the #MeToo movement in China. Asian Journal of Women’s Studies, 25(1), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/12259276.2019.1573002

Why is #MeToo Different in China? (2018, January 24). RADII | Stories from the Center of China’s Youth Culture. https://radiichina.com/why-is-metoo-different-in-china/

0 notes

Text

University students use social media platforms for political engagement

https://sites.bu.edu/cmcs/2018/11/17/do-social-media-influence-citizens-political-participation/

The constant growth and development of the Internet has simultaneously changed the way citizens participate in politics. This includes the use of social platforms to participate in politics. Facebook and Twitter, for example, allow users to vote directly on the platforms as well as creating a virtual space for communication. This approach has not only given citizens more ways to participate in politics, but has also increased the process of democratic participation. In this regard, the 2008 US presidential election used digital media as the basis for campaigning for the election. While social media and the internet have been used in previous presidential elections, the 2008 election's use of the internet and social platforms was central to its campaign. As a result, as the internet has become more widely used, it has also become an increasingly important tool for success in political campaigns.

From 1996 to 2008, the percentage of Americans getting their political information from the Internet rose from 4% to 40%. The internet has become an important source of access to political information (Rainie, 2007a; Smith & Rainie, 2008). Among young people in particular, 27% of those under 30 primarily get their campaign information from social networks. 97% of US teenagers aged 13-17 have used at least one major social media platform, and teenagers are among the largest users of the internet in the population(Nguyen, 2020).

https://evergreen.greenhill.org/the-political-power-of-social-media/

However, social media has been used as a source of political communication since 2008, and candidates from almost all major political parties began using social media during the campaign period in the same year (Kushin & Yamamoto, 2010). Especially during the campaign period, there is now a significant increase in the expression function, with 15% of Americans using the Internet at least once a week to promote the candidate they support.People use social media to promote political ideas, with the largest proportion of young people under 30, and people can use social media not only to seek information but also to interact with others in the form of online expression.

Scholars have argued that the Internet is a democratising medium that can provide more information and interaction, and that it can be used to express one's views while substituting one's own political views. As the internet provides new access to political news, not only can people receive political news from traditional news, but they can also participate in their favourite topics on social media platforms. This not only brings them closer to politics, but young people can also add political topics that interest them to their daily lives(Diehl et al., 2018). However, when young people use social media they are reluctant to actively search for news related to politics, but will instead click on the tweets of social media apps in general.

With social media becoming a significant force in political elections, young people's political participation is gradually playing an important role. Although the political decisions in which young people are involved on social media do not have far-reaching effects, As Shah(2016) says, conversation is the soul of democracy, whether face-to-face or online, and calls for active citizen participation in politics.

Reference

Diehl, T., Barnidge, M., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2018). Multi-Platform News Use and Political Participation Across Age Groups: Toward a Valid Metric of Platform Diversity and Its Effects. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 96(2), 428–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018783960

Kushin, M. J., & Yamamoto, M. (2010). Did Social Media Really Matter? College Students’ Use of Online Media and Political Decision Making in the 2008 Election. Mass Communication and Society, 13(5), 608–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2010.516863

Nguyen, E. (2020, November 16). The Political Power of Social Media. The Evergreen Online. https://evergreen.greenhill.org/the-political-power-of-social-media/

Shah, D. (2016). Conversation is the soul of democracy: Expression effects, communication mediation, and digital media. Communication And The Public, 1(1), 12-18. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057047316628310

0 notes

Text

Social media is an important way for black people to get involved in politics

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/09/27/support-for-black-lives-matter-declined-after-george-floyd-protests-but-has-remained-unchanged-since/

2014 Eric·Garner's murder by NYPD, 2015 Freddie·Gray's death after suffering spinal injuries in the back of a police car in Baltimore to 2020 Black George· Floyd's murder by a white police officer in Minneapolis, all sparked a considerable impact on social media platforms and these impacts have continued offline. And social media is a very important platform for black users as they can engage with topics that are relevant to them online and find people who share their views. Likewise, black users can use social media platforms to speak out on behalf of minority groups. As a result, an online community known as 'Black Twitter' has been using social media platforms to organise, support and focus on issues relevant to black people.

Social media platforms provide users with the ability to inform and communicate, and people can use social media to produce and distribute content rather than being passive consumers of media. When they use tools to express their opinions and comment on and share other people's posts, they can not only change their user status but also show their support for a group on political issues (Hong & Kim, 2021). Online participation can be more cost effective than traditional participation. According to Vicente and Novo (2014), political participation online is often simply expressing one's opinion by liking posts on relevant political issues. And in this digital age, both online and offline activities are often relevant. For example, in the summer of 2020, thousands of protesters gathered across the country to protest against the 'Black Lives Matter' movement, which was connected from online to offline.

In a June 2020 survey asking about four types of political campaigns, the black social user group was one of the most likely to use the platform to bring issues and causes to the campaign. The group of black users who engage with the types of campaigns online also varies by age, with younger users more likely to come to do so than older users. And 48% of users said that they had posted photos on social media before the survey to show their support for something. And similar data is showing that they will take action on issues that are important to them and look for it online, with rallies or protests happening in their area (Auxier, 2020).

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/12/11/social-media-continue-to-be-important-political-outlets-for-black-americans/

Existing research has shown that social media can help shape politically relevant topics, acting as a 'public space' not only to disseminate information about movements or actions, but also to play a discursive role in shaping the issues raised by social movements. It has allowed more and more diverse groups to use social media as a platform to make their voices heard, and has also allowed more people to see the views of minorities on different issues. And, when the black community uses social media, they see these sites as an effective tool for political advocacy. In most cases, using social media has changed their views on politics or other issues to some extent.

Reference

Auxier, B. (2020, December 11). Social media continue to be important political outlets for Black Americans. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/12/11/social-media-continue-to-be-important-political-outlets-for-black-americans/

Hong, H., & Kim, Y. (2021). What makes people engage in civic activism on social media? Online Information Review, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/oir-03-2020-0105

Voorveld, H.A., van Noort, G., Muntinga, D.G. and Bronner, F. (2018), “Engagement with social media and social media advertising: the differentiating role of platform type”, Journal of Advertising, Vol. 47 No. 1, pp. 38-54.

0 notes

Text

Are you in a social media filter bubble?

According to a recent Pew Research Center survey on news consumption, 62% of adults in the US use social media to get their news, and 66% of Facebook users use the platform for news consumption. At the same time, as social media becomes a larger share of news and information consumption, social networks show an increasing ideological polarisation. In recent years, social media filter bubbles have been influencing people's daily browsing, including harmful content promoted by algorithms. A few days ago, photo-sharing program instagram said they would allow users to freely switch between messages that are arranged in chronological order, rather than being pushed according to a computer algorithm. In response, the UK Parliament has proposed the introduction of an Internet Safety Bill to protect children and adults from viewing information about harmful and illegal internet content.

Regarding the term 'filter bubble', Pariser (2011 ) states that "you live in an online, personal and unique world of information. What's in your filter bubble depends on who you are and what you do. At the same time, you don't get to decide what gets entered. What's more, you don't actually see what gets censored."He argues that the algorithms that customise and personalise the experience place users in a bubble where they will only see information that interests them or matches what they have seen before. This format creates an online form of isolation from differing opinions. As the concept focuses on the influence of the algorithm, people tend to share and discuss with people who have the same group when they choose articles that match their concerns(Seargeant & Tagg, 2019). To a certain extent, filter bubbles create 'echo chambers' for the exchange of opinions and provide a good place for communication. However, the concept of filter bubbles has also had to face some real problems. Some social media giants, including Google, Facebook and Twitter, are using ever-changing algorithms that ultimately create these filter bubbles. Facebook, for example, prefers to push news with the same political beliefs to users when they are browsing for information, and in particular tends to amplify news stories preferred by the same political partners in terms of news algorithms.

https://www.ted.com/talks/eli_pariser_what_obligation_do_social_media_platforms_have_to_the_greater_good?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

In response, Strohma(2019) also said that the reality is that social media platforms are providing users with information that matches their interests and can be collected from other social media followers and fed back to users, and that users who use the platforms are like having hundreds of friends. There is no way to change the impact of the algorithm while the user is using it. However, Strohma suggests that people can try to break out of these bubbles to limit people's access.

http://www.ftchinese.com/interactive/56298?exclusive

With the introduction of the Government's Online Safety Bill, the media regulator will regulate these social platforms, which will change the way information is pushed. Users will have the right to choose the communities they want to participate in discussions with, as well as the ability to change the original fixed message push by searching for sources of information, and to communicate with people with different views and access different aspects of information. All of this helps users to break the algorithms of social platforms in their own way.

Reference

Seargeant, P., & Tagg, C. (2019). Social media and the future of open debate: A user-oriented approach to Facebook’s filter bubble conundrum. Discourse, Context & Media, 27, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2018.03.005

Gould, W. R. (2019, October 21). Are you in a social media bubble? Here’s how to tell. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/better/lifestyle/problem-social-media-reinforcement-bubbles-what-you-can-do-about-ncna1063896

Schiffer, Z. (2019, November 12). “Filter Bubble” author Eli Pariser on why we need publicly owned social networks. The Verge; The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/interface/2019/11/12/20959479/eli-pariser-civic-signals-filter-bubble-q-a

1 note

·

View note

Text

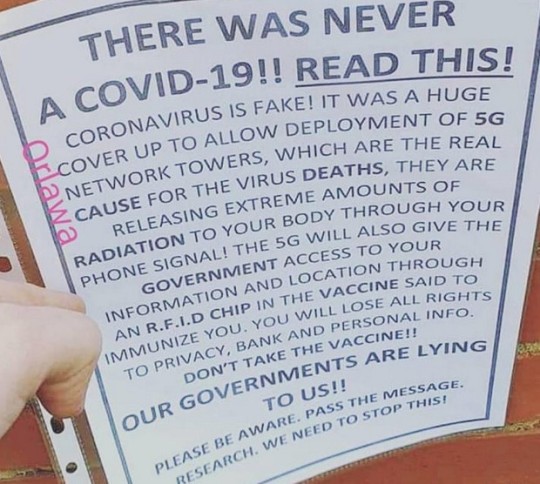

Fake news during the pandemic

Since the 2016 US presidential election, the term 'fake news' has become a global staple. Fake news is a form of propaganda that falsely validates trust and creates illusions about people's worldviews by questioning the foundations of their ideology and moral constructs(Lewandowsky et al., 2017).Fundamentally, however, the concept of fake news is still different from that of disinformation. From an academic perspective, the idea is often summarised as describing a piece of misleading information i.e. misinformation.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the World Health Organisation not only informed the public of the seriousness of the new Covidium epidemic, but also stressed the importance of limiting the spread of misinformation. Humanity is thus not only battling a virus, but also struggling with a socially, politically and economically unstable social environment that is not devoid of misinformation. As barriers to accessing media and news have become lower in the digital age, the freedom of information exchange has created the perfect timing for the spread of disinformation during a pandemic. Disinformation is spread through different platforms and types of disinformation. For example, 'eating garlic can cure COVID-19 overnight', 'hold your breath for 10 seconds to check for the virus', etc. In an information age that values public health, it is easier for people to get misinformation from social media than to confirm the truth. In response, Lazer(2018)said that when the mainstream media tries to debate fake news, the spread of misinformation becomes a more powerful party

https://www.brixtonbuzz.com/2020/09/coronavirus-and-conspiracy-theories-an-essential-read-for-rebutting-social-media-madness/

The Covid-19 outbreak has resulted in an upsurge in misinformation and anti-mask, anti-vaccine, and anti-5G protest attitude throughout the world. Anti-vaccination attitude is not a new phenomena; before to the COVID-19 epidemic, the World Health Organization identified "vaccine hesitancy" as one of the most serious global health dangers. With the proliferation of internet media, these venues are being utilised to sow the seeds of sociopolitical conflict. Because of its polished production and speedy dissemination, the documentary film "The Plague" has received millions of viewers on internet sites. Scientists and journalists alike were perplexed when the video went viral. Gamiki Willis, a conspirator, created the documentary. Former scientist Judy Mickiewicz appears in the documentary, which was created by a conspirator named Gamiki Willis. It stars Dr. Judy Mickiewicz, a former scientist.The movie is a brief documentary about the risks of wearing masks and getting vaccinated. Mikowitz says that wearing a mask will cause the virus to self-activate since the vaccination weakens the immune system. In the video, she also alleges that the outbreak is the result of a plot orchestrated by major pharmaceutical firms and the World Health Organization.

Conspiracy theories are a sort of deception, and they are typically not founded on science or facts. However, this does not prevent them from having a huge impact on society (Brainard & Hunter, 2019). According to research, over 60% of the British population believes in at least one conspiracy, and the percentage is significantly greater in the United States and abroad (Addley, 2018). The rise of conspiracy theories should serve as a wake-up call to governments, the general public, the populace, and social media platforms alike. Not only must action be taken to educate the people, but also to hasten the construction of a global network of disinformation observers. Although, as one could expect, developing this procedure is more complex than one may anticipate. The active use of mass media to promote truth and communication, on the other hand, is required to break the chain of social networks and misinformation transmission.

Reference

Addley, E. (2018, November 23). Study shows 60% of Britons believe in conspiracy theories. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/nov/23/study-shows-60-of-britons-believe-in-conspiracy-theories

Brainard, J., & Hunter, P. R. (2019). Misinformation making a disease outbreak worse: outcomes compared for influenza, monkeypox, and norovirus. SIMULATION, 96(4), 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0037549719885021

Das, R., & Ahmed, W. (2021). Rethinking Fake News: Disinformation and Ideology during the time of COVID-19 Global Pandemic. IIM Kozhikode Society & Management Review, 227797522110273. https://doi.org/10.1177/22779752211027382

Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C. R., Thorson, E. A., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the “Post-Truth” Era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

1 note

·

View note