likeabook

1K posts

Life is like a book, it has us turning the pages. My stuff Please do not repost anywhere without permission, thx.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

i am always fascinated by the notion of one particular technological or scientific revelation fundamentally changing how humans interact with the world, because this often gets associated with only the last hundred years of human history - as if ipads have changed the world irreversibly, but discovering that there were in fact seven continents and not two did not.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Every complex ecosystem has parasites

I'm on a 20+ city book tour for my new novel PICKS AND SHOVELS. Catch me at NEW ZEALAND'S UNITY BOOKS in AUCKLAND on May 2, and in WELLINGTON on May 3. More tour dates (Pittsburgh, PDX, London, Manchester) here.

Patrick "patio11" McKenzie is a fantastic explainer, the kind of person who breaks topics down in ways that stay with you, and creep into your understanding of other subjects, too. Take his 2022 essay, "The optimal amount of fraud is non-zero":

https://www.bitsaboutmoney.com/archive/optimal-amount-of-fraud/

It's a very well-argued piece, and here's the nut of it:

The marginal return of permitting fraud against you is plausibly greater than zero, and therefore, you should welcome greater than zero fraud.

In other words, if you allow some fraud, you will also allow through a lot of non-fraudulent business that would otherwise trip your fraud meter. Or, put it another way, the only way to prevent all fraud is to chase away a large proportion of your customers, whose transactions are in some way abnormal or unexpected.

Another great explainer is Bruce Schneier, the security expert. In the wake of 9/11, lots of pundits (and senior government officials) ran around saying, "No price is too high to prevent another terrorist attack on our aviation system." Schneier had a foolproof way of shutting these fools up: "Fine, just ground all civilian aircraft, forever." Turns out, there is a price that's too high to pay for preventing air-terrorism.

Latent in these two statements is the idea that the most secure systems are simple, and while simplicity is a fine goal to strive for, we should always keep in mind the maxim attributed to Einstein, "Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler." That is to say, some things are just complicated.

20 years ago, my friend Kathryn Myronuk and I were talking about the spam wars, which were raging at the time. The spam wars were caused by the complexity of email: as a protocol (rather than a product), email is heterogenuous. There are lots of different kinds of email servers and clients, and many different ways of creating and rendering an email. All this flexibility makes email really popular, and it also means that users have a wide variety of use-cases for it. As a result, identifying spam is really hard. There's no reliable automated way of telling whether an email is spam or not – you can't just block a given server, or anyone using a kind of server software, or email client. You can't choose words or phrases to block and only block spam.

Many solutions were proposed to this at the height of the spam wars, and they all sucked, because they all assumed that the way the proposer used email was somehow typical, thus we could safely build a system to block things that were very different from this "typical" use and not catch too many dolphins in our tuna nets:

https://craphound.com/spamsolutions.txt

So Kathryn and I were talking about this, and she said, "Yeah, all complex ecosystems have parasites." I was thunderstruck. The phrase entered my head and never left. I even gave a major speech with that title later that year, at the O'Reilly Emerging Technology Conference:

https://craphound.com/complexecosystems.txt

Truly, a certain degree of undesirable activity is the inevitable price you pay once you make something general purpose, generative, and open. Open systems – like the web, or email – succeed because they are so adaptable, which means that all kinds of different people with different needs find ways to make use of them. The undesirable activity in open systems is, well, undesirable, and it's valid and useful to try to minimize it. But minimization isn't the same as elimination. "The optimal amount of fraud is non-zero," because "everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler." Complexity is generative, but "all complex ecosystems have parasites."

America is a complex system. It has, for example, a Social Security apparatus that has to serve more than 65 million people. By definition, a cohort of 65 million people will experience 65 one-in-a-million outliers every day. Social Security has to accommodate 65 million variations on the (surprisingly complicated) concept of a "street address":

https://gist.github.com/almereyda/85fa289bfc668777fe3619298bbf0886

It will have to cope with 65 million variations on the absolutely, maddeningly complicated idea of a "name":

https://www.kalzumeus.com/2010/06/17/falsehoods-programmers-believe-about-names/

In cybernetics, we say that a means of regulating a system must be capable of representing as many states as the system itself – that is, if you're building a control box for a thing with five functions, the box needs at least five different settings:

http://pespmc1.vub.ac.be/REQVAR.html

So when we're talking about managing something as complicated as Social Security, we need to build a Social Security Administration that is just as complicated. Anything that complicated is gonna have parasites – once you make something capable of managing the glorious higgeldy piggeldy that is the human experience of names, dates of birth, and addresses, you will necessarily create exploitable failure modes that bad actors can use to steal Social Security. You can build good fraud detection systems (as the SSA has), and you can investigate fraud (as the SSA does), and you can keep this to a manageable number – in the case of the SSA, that number is well below one percent:

https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/IF/PDF/IF12948/IF12948.2.pdf

But if you want to reduce Social Security fraud from "a fraction of one percent" to "zero percent," you can either expend a gigantic amount of money (far more than you're losing to fraud) to get a little closer to zero – or you can make Social Security far simpler. For example, you could simply declare that anyone whose life and work history can't fit in a simple database schema is not eligible for Social Security, kick tens of millions of people off the SSI rolls, and cause them to lose their homes and starve on the streets. This isn't merely cruel, it's also very, very expensive, since homelessness costs the system far more than Social Security. The optimum amount of fraud is non-zero.

Conservatives hate complexity. That's why the Trump administration banned all research grants for proposals that contained the word "systemic" (as a person with so-far-local cancer, I sure worry about what happens when and if my lymphoma become systemic). I once described the conservative yearning for "simpler times," as a desire to be a child again. After all, the thing that made your childhood "simpler" wasn't that the world was less complicated – it's that your parents managed that complexity and shielded you from it. There's always been partner abuse, divorce, gender minorities, mental illness, disability, racial discrimination, geopolitical crises, refugees, and class struggle. The only people who don't have to deal with this stuff are (lucky) children.

Complexity is an unavoidable attribute of all complicated processes. Evolution is complicated, so it produces complexity. It's convenient to think about a simplified model of genes in which individual genes produce specific traits, but it turns out genes all influence each other, are influenced in turn by epigenetics, and that developmental factors play a critical role in our outcomes. From eye-color to gender, evolution produces spectra, not binaries. It's ineluctably (and rather gloriously) complicated.

The conservative project to insist that things can be neatly categorized – animal or plant, man or woman, planet or comet – tries to take graceful bimodal curves and simplify them into a few simple straight lines – one or zero (except even the values of the miniature transistors on your computer's many chips are never at "one" or "zero" – they're "one-ish" and "mostly zero").

Like Social Security, fraud in the immigration system is a negligible rounding error. The US immigration system is a baroque, ramified, many-tendriled thing (I have the receipts from the immigration lawyers who helped me get a US visa, a green card, and citizenship to prove it). It is already so overweighted with pitfalls and traps for the unwary that a good immigration lawyer might send you to apply for a visa with 600 pages of documentation (the most I ever presented) just to make sure that every possible requirement is met:

https://www.flickr.com/photos/doctorow/2242342898/in/photolist-zp6PxJ-4q9Aqs-2nVHTZK-2pFKHyf

After my decades of experience with the US immigration system, I am prepared to say that the system is now at a stage where it is experiencing sharply diminishing returns from its anti-fraud systems. The cost of administering all this complexity is high, and the marginal amount of fraud caught by any new hoop the system gins up for migrants to jump through will round to zero.

Which poses a problem for Trump and trumpists: having whipped up a national panic about out of control immigration and open borders, the only way to make the system better at catching the infinitesimal amount of fraud it currently endures is to make the rules simpler, through the blunt-force tactic of simply excluding people who should be allowed in the country. For example, you could ban college kids planning to spend the summer in the US on the grounds that they didn't book all their hotels in advance, because they're planning to go from city to city and wing it:

https://www.newsweek.com/germany-tourists-deported-hotel-maria-lepere-charlotte-pohl-hawaii-2062046

Or you could ban the only research scientist in the world who knows how to interpret the results of the most promising new cancer imaging technology because a border guard was confused about the frog embryos she was transporting (she's been locked up for two months now):

https://www.msn.com/en-us/health/other/horrified-harvard-scientists-ice-arrest-leaves-cancer-researchers-scrambling/ar-AA1DlUt8

Of course, the US has long operated a policy of "anything that confuses a border guard is grounds for being refused entry" but the Trump administration has turned the odd, rare outrage into business-as-usual.

But they can lock up or turn away as many people as they want, and they still won't get the amount of fraud to zero. The US is a complicated place. People have complicated reasons for entering the USA – work, family reunion, leisure, research, study, and more. The only immigration system that doesn't leak a little at the seams is an immigration system that is so simple that it has no seams – a toy immigration system for a trivial country in which so little is going on that everything is going on.

The only garden without weeds is a monoculture under a dome. The only email system without spam is a closed system managed by one company that only allows a carefully vetted cluster of subscribers to communicate with one another. The only species with just two genders is one wherein members who fit somewhere else on the spectrum are banished or killed, a charnel process that never ends because there are always newborns that are outside of the first sigma of the two peaks in the bimodal distribution.

A living system – a real country – is complicated. It's a system, where people do things you'll never understand for perfectly good reasons (and vice versa). To accommodate all that complexity, we need complex systems, and all complex ecosystems have parasites. Yes, you can burn the rainforest to the ground and planting monocrops in straight rows, but then what you have is a farm, not a forest, vulnerable to pests and plagues and fire and flood. Complex systems have parasites, sure, but complex systems are resilient. The optimal level of fraud is never zero, because a system that has been simplified to the point where no fraud can take place within it is a system that is so trivial and brittle as to be useless.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/04/24/hermit-kingdom/#simpler-times

584 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sarah Wynn-Williams’s ‘Careless People’

I'm on a 20+ city book tour for my new novel PICKS AND SHOVELS. Catch me at NEW ZEALAND'S UNITY BOOKS in AUCKLAND on May 2, and in WELLINGTON on May 3. More tour dates (Pittsburgh, PDX, London, Manchester) here.

I never would have read Careless People, Sarah Wynn-Williams's tell-all memoir about her years running global policy for Facebook, but then Meta's lawyer tried to get the book suppressed and secured an injunction to prevent her from promoting it:

https://www.npr.org/2025/03/14/nx-s1-5318854/former-meta-executive-barred-from-discussing-criticism-of-the-company

So I've got something to thank Meta's lawyers for, because it's a great book! Not only is Wynn-Williams a skilled and lively writer who spills some of Facebook's most shameful secrets, but she's also a kick-ass narrator (I listened to the audiobook, which she voices):

https://libro.fm/audiobooks/9781250403155-careless-people

I went into Careless People with strong expectations about the kind of disgusting behavior it would chronicle. I have several friends who took senior jobs at Facebook, thinking they could make a difference (three of them actually appear in Wynn-Williams's memoir), and I've got a good sense of what a nightmare it is for a company.

But Wynn-Williams was a lot closer to three of the key personalities in Facebook's upper echelon than anyone in my orbit: Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, and Joel Kaplan, who was elevated to VP of Global Policy after the Trump II election. I already harbor an atavistic loathing of these three based on their public statements and conduct, but the events Wynn-Williams reveals from their private lives make these three out to be beyond despicable. There's Zuck, whose underlings let him win at board-games like Settlers of Catan because he's a manbaby who can't lose (and who accuses Wynn-Williams of cheating when she fails to throw a game of Ticket to Ride while they're flying in his private jet. There's Sandberg, who demands the right to buy a kidney for her child from someone in Mexico, should that child ever need a kidney.

Then there's Kaplan, who is such an extraordinarily stupid and awful oaf that it's hard to pick out just one example, but I'll try. At one point, Wynn-Williams gets Zuck a chance to address the UN General Assembly. As is his wont, Zuck refuses to be briefed before he takes the dais (he's repeatedly described as unwilling to consider any briefing note longer than a single text message). When he gets to the mic, he spontaneously promises that Facebook will provide internet access to refugees all over the world. Various teams at Facebook then race around, trying to figure out whether this is something the company is actually doing, and once they realize Zuck was just bullshitting, set about trying to figure out how to do it. They get some way down this path when Kaplan intervenes to insist that giving away free internet to refugees is a bad idea, and that instead, they should sell internet access to refugees. Facebookers dutifully throw themselves into this absurd project, which dies when Kaplan fires off an email stating that he's just realized that refugees don't have any money. The project dies.

The path that brought Wynn-Williams's into the company of these careless people is a weird – and rather charming – one. As a young woman, Wynn-Williams was a minor functionary in the New Zealand diplomatic corps, and during her foreign service, she grew obsessed with the global political and social potential of Facebook. She threw herself into the project of getting hired to work on Facebook's global team, working on strategy for liaising with governments around the world. The biggest impediment to landing this job is that it doesn't exist: sure, FB was lobbying the US government, but it was monumentally disinterested in the rest of the world in general, and the governments of the world in particular.

But Wynn-Williams persists, pestering potentially relevant execs with requests, working friends-of-friends (Facebook itself is extraordinarily useful for this), and refusing to give up. Then comes the Christchurch earthquake. Wynn-Williams is in the US, about to board a flight, when her sister, a news presenter, calls her while trapped inside a collapsed building (the sister hadn't been able to get a call through to anyone in NZ). Wynn-Williams spends the flight wondering if her sister is dead or alive, and only learns that her sister is OK through a post on Facebook.

The role Facebook played in the Christchurch quake transforms Wynn-Williams's passion for Facebook into something like religious zealotry. She throws herself into the project of landing the job, and she does, and after some funny culture-clashes arising from her Kiwi heritage and her public service background, she settles in at Facebook.

Her early years there are sometimes comical, sometimes scary, and are characteristic of a company that is growing quickly and unevenly. She's dispatched to Myanmar amidst a nationwide block of Facebook ordered by the ruling military junta and at one point, it seems like she's about to get kidnapped and imprisoned by goons from the communications ministry. She arranges for a state visit by NZ Prime Minister John Key, who wants a photo-op with Zuckerberg, who – oblivious to the prime minister standing right there in front of him – berates Wynn-Williams for demanding that he meet with some jackass politician (they do the photo-op anyway).

One thing is clear: Facebook doesn't really care about countries other than America. Though Wynn-Williams chalks this up to plain old provincial chauvinism (which FB's top echelon possess in copious quantities), there's something else at work. The USA is the only country in the world that a) is rich, b) is populous, and c) has no meaningful privacy protections. If you make money selling access to dossiers on rich people to advertisers, America is the most important market in the world.

But then Facebook conquers America. Not only does FB saturate the US market, it uses its free cash-flow and high share price to acquire potential rivals, like Whatsapp and Instagram, ensuring that American users who leave Facebook (the service) remain trapped by Facebook (the company).

At this point, Facebook – Zuckerberg – turns towards the rest of the world. Suddenly, acquiring non-US users becomes a matter of urgency, and overnight Wynn-Williams is transformed from the sole weirdo talking about global markets to the key asset in pursuit of the company's top priority.

Wynn-Williams's explanation for this shift lies in Zuckerberg's personality, his need to constantly dominate (which is also why his subordinates have learned to let him win at board games). This is doubtless true: not only has this aspect of Zuckerberg's personality been on display in public for decades, Wynn-Williams was able to observe it first-hand, behind closed doors.

But I think that in addition to this personality defect, there's a material pressure for Facebook to grow that Wynn-Williams doesn't mention. Companies that grow get extremely high price-to-earnings (P:E) ratios, meaning that investors are willing to spend many dollars on shares for every dollar the company takes in. Two similar companies with similar earnings can have vastly different valuations (the value of all the stock the company has ever issued), depending on whether one of them is still growing.

High P:E ratios reflect a bet on the part of investors that the company will continue to grow, and those bets only become more extravagant the more the company grows. This is a huge advantage to companies with "growth stocks." If your shares constantly increase in value, they are highly liquid – that is, you can always find someone who's willing to buy your shares from you for cash, which means that you can treat shares like cash. But growth stocks are better than cash, because money grows slowly, if at all (especially in periods of extremely low interest rates, like the past 15+ years). Growth stocks, on the other hand, grow.

Best of all, companies with growth stocks have no trouble finding more stock when they need it. They just type zeroes into a spreadsheet and more shares appear. Contrast this with money. Facebook may take in a lot of money, but the money only arrives when someone else spends it. Facebook's access to money is limited by exogenous factors – your willingness to send your money to Facebook. Facebook's access to shares is only limited by endogenous factors – the company's own willingness to issue new stock.

That means that when Facebook needs to buy something, there's a very good chance that the seller will accept Facebook's stock in lieu of US dollars. Whether Facebook is hiring a new employee or buying a company, it can outbid rivals who only have dollars to spend, because that bidder has to ask someone else for more dollars, whereas Facebook can make its own stock on demand. This is a massive competitive advantage.

But it is also a massive business risk. As Stein's Law has it, "anything that can't go on forever eventually stops." Facebook can't grow forever by signing up new users. Eventually, everyone who might conceivably have a Facebook account will get one. When that happens, Facebook will need to find some other way to make money. They could enshittify – that is, shift value from the company's users and customers to itself. They could invent something new (like metaverse, or AI). But if they can't make those things work, then the company's growth will have ended, and it will instantaneously become grossly overvalued. Its P:E ratio will have to shift from the high value enjoyed by growth stocks to the low value endured by "mature" companies.

When that happens, anyone who is slow to sell will lose a ton of money. So investors in growth stocks tend to keep one fist poised over the "sell" button and sleep with one eye open, watching for any hint that growth is slowing. It's not just that growth gives FB the power to outcompete rivals – it's also the case that growth makes the company vulnerable to massive, sudden devaluations. What's more, if these devaluations are persistent and/or frequent enough, the key FB employees who accepted stock in lieu of cash for some or all of their compensation will either demand lots more cash, or jump ship for a growing rival. These are the very same people that Facebook needs to pull itself out of its nosedives. For a growth stock, even small reductions in growth metrics (or worse, declines) can trigger cascades of compounding, mutually reinforcing collapse.

This is what happened in early 2022, when Meta posted slightly lower-than-anticipated US growth numbers, and the market all pounded on the "sell" button at once, lopping $250,000,000 of the company's valuation in 24 hours. At the time, it was the worst-ever single day losses for any company in human history:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/sergeiklebnikov/2022/02/03/facebook-faces-an-existential-moment-after-230-billion-stock-crash/

Facebook's conquest of the US market triggered an emphasis on foreign customers, but not just because Zuck is obsessed with conquest. For Facebook, a decline in US growth posed an existential risk, the possibility of mass stock selloffs and with them, the end of the years in which Facebook could acquire key corporate rivals and executives with "money" it could print on the premises, on demand.

So Facebook cast its eye upon the world, and Wynn-Williams's long insistence that the company should be paying attention to the political situation abroad suddenly starts landing with her bosses. But those bosses – Zuck, Sandberg, Kaplan and others – are "careless." Zuck screws up opportunity after opportunity because he refuses to be briefed, forgets what little information he's been given, and blows key meetings because he refuses to get out of bed before noon. Sandberg's visits to Davos are undermined by her relentless need to promote herself, her "Lean In" brand, and her petty gamesmanship. Kaplan is the living embodiment of Green Day's "American Idiot" and can barely fathom that foreigners exist.

Wynn-Williams's adventures during this period are very well told, and are, by turns, harrowing and hilarious. Time and again, Facebook's top brass snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, squandering incredible opportunities that Wynn-Williams secures for them because of their pettiness, short-sightedness, and arrogance (that is, their carelessness).

But Wynn-Williams's disillusionment with Facebook isn't rooted in these frustrations. Rather, she is both personally and professionally aghast at the company's disgusting, callous and cruel behavior. She describes how her boss, Joel Kaplan, relentlessly sexually harasses her, and everyone in a position to make this stop tells her to shut up and take it. When Wynn-Williams give birth to her second child, she hemorrhages, almost dies, and ends up in a coma. Afterwards, Kaplan gives her a negative performance review because she was "unresponsive" to his emails and texts while she was dying in an ICU. This is a significant escalation of the earlier behavior she describes, like pestering her with personal questions about breastfeeding, video-calling her from bed, and so on (Kaplan is Sandberg's ex-boyfriend, and Wynn-Williams describes another creepy event where Sandberg pressures her to sleep next to her in the bedroom on one of Facebook's jet, something Wynn-Williams says she routinely does with the young women who report to her).

Meanwhile, Zuck is relentlessly pursuing Facebook's largest conceivable growth market: China. The only problem: China doesn't want Facebook. Zuck repeatedly tries to engineer meetings with Xi Jinping so he can plead his case in person. Xi is monumentally hostile to this idea. Zuck learns Mandarin. He studies Xi's book, conspicuously displays a copy of it on his desk. Eventually, he manages to sit next to Xi at a dinner where he begs Xi to name his next child. Xi turns him down.

After years of persistent nagging, lobbying, and groveling, Facebook's China execs start to make progress with a state apparatchik who dangles the possibility of Facebook entering China. Facebook promises this factotum the world – all the surveillance and censorship the Chinese state wants and more. Then, Facebook's contact in China is jailed for corruption, and they have to start over.

At this point, Kaplan has punished Wynn-Williams – she blames it on her attempts to get others to force him to stop his sexual harassment – and cut her responsibilities in half. He tries to maneuver her into taking over the China operation, something he knows she absolutely disapproves of and has refused to work on – but she refuses. Instead, she is put in charge of hiring the new chief of China operations, giving her access to a voluminous paper-trail detailing the company's dealings with the Chinese government.

According to Wynn-Williams, Facebook actually built an extensive censorship and surveillance system for the Chinese state – spies, cops and military – to use against Chinese Facebook users, and FB users globally. They promise to set up caches of global FB content in China that the Chinese state can use to monitor all Facebook activity, everywhere, with the implication that they'll be able to spy on private communications, and censor content for non-Chinese users.

Despite all of this, Facebook is never given access to China. However, the Chinese state is able to use the tools Facebook built for it to attack independence movements, the free press and dissident uprisings in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Meanwhile, in Myanmar, a genocide is brewing. NGOs and human rights activists keep reaching out to Facebook to get them to pay attention to the widespread use of the platform to whip up hatred against the country's Muslim minority group, the Rohinga. Despite having expended tremendous amounts of energy to roll out "Free Basics" in Myanmar (a program whereby Facebook bribes carriers to exclude its own services from data caps), with the result that in Myanmar, "the internet" is synonymous with "Facebook," the company has not expended any effort to manage its Burmese presence. The entire moderation staff consists of one (later two) Burmese speakers who are based in Dublin and do not work local hours (later, these two are revealed as likely stooges for the Myanmar military junta, who are behind the genocide plans).

The company has also failed to invest in Burmese language support for its systems – posts written in Burmese script are not stored as Unicode, meaning that none of the company's automated moderation systems can parse it. The company is so hostile to pleas to upgrade these systems that Wynn-Williams and some colleagues create secret, private Facebook groups where they can track the failures of the company and the rising tide of lethal violence in the country (this isn't the only secret dissident Facebook group that Wynn-Williams joins – she's also part of a group of women who have been sexually harassed by colleagues and bosses).

The genocide that follows is horrific beyond measure. And, as with the Trump election, the company's initial posture is that they couldn't possibly have played a significant role in a real-world event that shocked and horrified its rank-and-file employees.

The company, in other words, is "careless." Warned of imminent harms to its users, to democracy, to its own employees, the top executives simply do not care. They ignore the warnings and the consequences, or pay lip service to them. They don't care.

Take Kaplan: after figuring out that the company can't curry favor with the world's governments by selling drone-delivered wifi to refugees (the drones don't fly and the refugees are broke), he hits on another strategy. He remakes "government relations" as a sales office, selling political ads to politicians who are seeking to win over voters, or, in the case of autocracies, disenfranchised hostage-citizens. This is hugely successful, both as a system for securing government cooperation and as a way to transform Facebook's global policy shop from a cost-center to a profit-center.

But of course, it has a price. Kaplan's best customers are dictators and would-be dictators, formenters of hatred and genocide, authoritarians seeking opportunities to purge their opponents, through exile and/or murder.

Wynn-Williams makes a very good case that Facebook is run by awful people who are also very careless – in the sense of being reckless, incurious, indifferent.

But there's another meaning to "careless" that lurks just below the surface of this excellent memoir: "careless" in the sense of "arrogant" – in the sense of not caring about the consequences of their actions.

To me, this was the most important – but least-developed – lesson of Careless People. When Wynn-Williams lands at Facebook, she finds herself surrounded by oafs and sociopaths, cartoonishly selfish and shitty people, who, nevertheless, have built a service that she loves and values, along with hundreds of millions of other people.

She's not wrong to be excited about Facebook, or its potential. The company may be run by careless people, but they are still prudent, behaving as though the consequences of screwing up matter. They are "careless" in the sense of "being reckless," but they care, in the sense of having a healthy fear (and thus respect) for what might happen if they fully yield to their reckless impulses.

Wynn-Williams's firsthand account of the next decade is not a story of these people becoming more reckless, rather, its a story in which the possibility of consequences for that recklessness recedes, and with it, so does their care over those consequences.

Facebook buys its competitors, freeing it from market consequences for its bad acts. By buying the places where disaffected Facebook users are seeking refuge – Instagram and Whatsapp – Facebook is able to insulate itself from the discipline of competition – the fear that doing things that are adverse to its users will cause them to flee.

Facebook captures its regulators, freeing it from regulatory consequences for its bad acts. By playing a central role in the electoral campaigns of Obama and then other politicians around the world, Facebook transforms its watchdogs into supplicants who are more apt to beg it for favors than hold it to account.

Facebook tames its employees, freeing it from labor consequences for its bad acts. As engineering supply catches up with demand, Facebook's leadership come to realize that they don't have to worry about workforce uprisings, whether incited by impunity for sexually abusive bosses, or by the company's complicity in genocide and autocratic oppression.

First, Facebook becomes too big to fail.

Then, Facebook becomes too big to jail.

Finally, Facebook becomes too big to care.

This is the "carelessness" that ultimately changes Facebook for the worse, that turns it into the hellscape that Wynn-Williams is eventually fired from after she speaks out once too often. Facebook bosses aren't just "careless" because they refuse to read a briefing note that's longer than a tweet. They're "careless" in the sense that they arrive at a juncture where they don't have to care who they harm, whom they enrage, who they ruin.

There's a telling anaecdote near the end of Careless People. Back in 2017, leaks revealed that Facebook's sales-reps were promising advertisers the ability to market to teens who felt depressed and "worthless":

https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2017/05/facebook-helped-advertisers-target-teens-who-feel-worthless/

Wynn-Williams is – rightly – aghast about this, and even more aghast when she sees the company's official response, in which they disclaim any knowledge that this capability was being developed and fire a random, low-level scapegoat. Wynn-Williams knows they're lying. She knows that this is a routine offering, one that the company routinely boasts about to advertisers.

But she doesn't mention the other lies that Facebook tells in this moment: for one thing, the company offers advertisers the power to target more teens than actually exist. The company proclaims the efficacy of its "sentiment analysis" tool that knows how to tell if teens are feeling depressed or "worthless," even though these tools are notoriously inaccurate, hardly better than a coin-toss, a kind of digital phrenology.

Facebook, in other words, isn't just lying to the public about what it offers to advertisers – it's lying to advertisers, too. Contra those who say, "if you're not paying for the product, you're the product," Facebook treats anyone it can get away with abusing as "the product" (just like every other tech monopolist):

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/14/luxury-surveillance/#liar-liar

Wynn-Williams documents so many instances in which Facebook's top executives lie – to the courts, to Congress, to the UN, to the press. Facebook lies when it is beneficial to do so – but only when they can get away with it. By the time Facebook was lying to advertisers about its depressed teen targeting tools, it was already colluding with Google to rig the ad market with an illegal tool called "Jedi Blue":

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jedi_Blue

Facebook's story is the story of a company that set out to become too big to care, and achieved that goal. The company's abuses track precisely with its market dominance. It enshittified things for users once it had the users locked in. It screwed advertisers once it captured their market. It did the media-industry-destroying "pivot to video" fraud once it captured the media:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pivot_to_video

The important thing about Facebook's carelessness is that it wasn't the result of the many grave personality defects in Facebook's top executives – it was the result of policy choices. Government decisions not to enforce antitrust law, to allow privacy law to wither on the vine, to expand IP law to give Facebook a weapon to shut down interoperable rivals – these all created the enshittogenic environment that allowed the careless people who run Facebook to stop caring.

The corollary: if we change the policy environment, we can make these careless people – and their successors, who run other businesses we rely upon – care. They may never care about us, but we can make them care about what we might do to them if they give in to their carelessness.

Meta is in global regulatory crosshairs, facing antitrust action in the USA:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/04/18/chatty-zucky/#is-you-taking-notes-on-a-criminal-fucking-conspiracy

And muscular enforcement pledges in the EU:

https://www.reuters.com/business/retail-consumer/eu-says-it-will-enforce-digital-rules-irrespective-ceo-location-2025-04-21/

As Martin Luther King, Jr put it:

The law cannot make a man love me, but it can stop him from lynching me, and I think that's pretty important.

If you'd like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here's a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2025/04/23/zuckerstreisand/#zdgaf

717 notes

·

View notes

Text

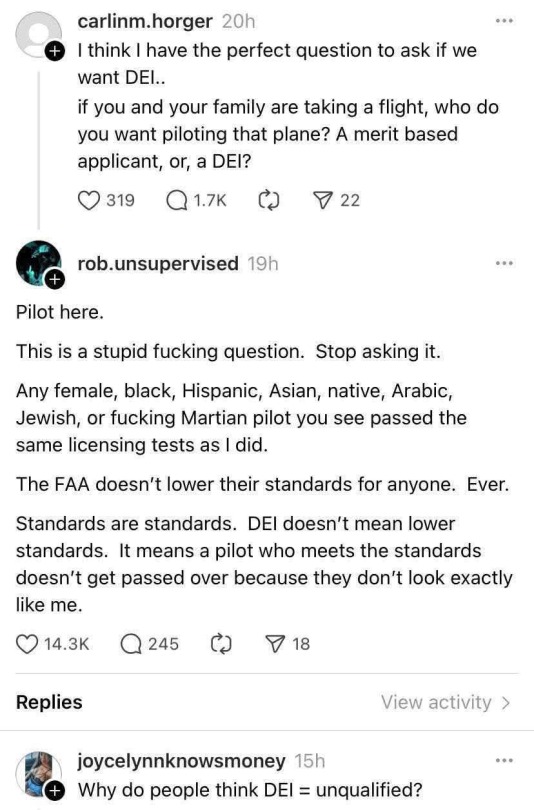

DEI does not mean lower standards.

You are thinking of white privilege.

36K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fanfic is a free hobby.

It's one of the last few things we can have as a society that's free. You can engage, for free. People give you things (art, stories, etc), for free.

Don't buy into the consummerism just because it's everywhere else.

You don't have to consume everything you interact with. You don't have to use things, just because they exist.

You're allowed (still, for now), to have things that are enjoyable for free.

Do you realise how insane the world is? We don't have many places where we can just be, for free anymore, but ao3 is. Did you notice we don't have ads in ao3? We don't have pop ups? Where ELSE do we not have that?

Where else can you just go and not have to wait for a commercial to be over or for ads to be on the sidelines?

I don't think the younger people understand, but the whole of internet used to be like this. YouTubers would do Youtube for free, just because. You couldn't monetise your internet presence before.

Ao3 is like a little preserved corner of the internet where the old internet used to be, and it's being attacked by people who do not understand that free things are allowed to exist without judgment.

Please don't ruin this for us.

Some of us need it.

6K notes

·

View notes

Photo

I needed this drag. Let’s change guys and not look back

219K notes

·

View notes

Text

How do they keep making later and later stages of late-capitalism

58K notes

·

View notes

Text

Vimes: I hate the rich, and nobility are pretty much just scum

Vetinari: let me be real funny for a moment

930 notes

·

View notes

Text

Body swap AU

Translation:

🐦⬛: Ah, Vimes. I hope you're already dealing with our problem.

🐶: Excuse me, sir?

🐦⬛: I need a decision until Wednesday.

🐶: Are you out of your mind?

🐦⬛: Yes, Vimes. I am obviously out of my mind and body.

🐶: Am I looking like a wizzard?!

2nd pic:

🐦⬛: Vimes, I strongly recommend you not to move.

🐶: Usually I prefer no assassins near my neck, sir. Especially with sharp things in their hands.

🐦⬛: Than you should learn how to shave yourself properly. Or hire a barber.

🐶: Are you sure that barber won't cut the throat of your Patrician's body for a few coins?

🐦⬛: Than sit still, Vimes.

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

wikipedia no longer being anywhere near the top of search results when looking up anything feels eviscerating

66K notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think authors sometimes don't realize how their, uh, interests creep into their writing? I'm talking about stuff like Robert Jordan's obvious femdom kink, or Anne Rice's preoccupation with inc*st and p*dophilia. Did their editors ever gently ask them if they've ever actually read what they've written?

Firstly, a reminder: This is not tiktok and we just say the words incest and pedophilia here.

Secondly, I don't know if I would call them 'interests' so much as fixations or even concerns. There are monstrous things that people think about, and I think writing is a place to engage with those monstrous things. It doesn't bother me that people engage with those things. I exist somewhere within the whump scale, and I would hope no one would think less of me just because sooner or later I like to rough a good character up a bit, you know? It's fun to torture characters, as a treat!

But, anyway, assuming this question isn't, "Do writers know they're gross when I think they are gross" which I'm going to take the kind road and assume it isn't, but is instead, "Do you think authors are aware of the things they constantly come back to?"

Sometimes. It can be jarring to read your own writing and realize that there are things you CLEARLY are preoccupied with. (mm, I like that word more than concerns). There are things you think about over and over, your run your mind over them and they keep working their way back in. I think this is true of most authors, when you read enough of them. Where you almost want to ask, "So...what's up with that?" or sometimes I read enough of someone's work that I have a PRETTY good idea what's up with that.

I've never read Robert Jordan and I don't intend to start (I think it would bore me this is not a moral stance) and I've really never read Rice's erotica. In erotica especially I think you have all the right in the world to get fucking weird about it! But so, when I was young I read the whole Vampire Chronicles series. I don't remember it perfectly, but there's plenty in it to reveal VERY plainly that Anne Rice has issues with God but deeply believes in God, and Anne Rice has a preoccupation with the idea of what should stay dead, and what it means to become. So, when i found out her daughter died at the age of six, before Rice wrote all of this, and she grew up very very Catholic' I said, 'yeah, that fucking checks out'.

Was Rice herself aware of how those things formed her writing? I think at a certain point probably yes. The character of Claudia is in every way too on the nose for her not to have SOME idea unless she was REAL REAL dense about her own inner workings. But, sometimes I know where something I write about comes from, that doesn't mean I'm interested in sharing it with the class. I would never ever fucking say, 'The reasons I seem to write so much of x as y is that z happened to me years ago' ahaha FUCK THAT NOISE. NYET. RIDE ON, COWBOY.

But I've known some people in fandom works who clearly have something going on and don't seem to realize it. Or they're very good at hiding it. Based on the people I'm talking about I would say it's more a lack of self-knowledge, and I don't even mean that unkindly. I have, in many ways, taken myself down to the studs and rebuilt it all, so I unfortunately am very aware of why I do and write the things I do most of the time. It's extremely annoying not to be able to blame something. I imagine it must be very freeing. But it ain't me, babe.

Anyway, a lot of words to say: Maybe! But that might not stop them from writing it, it might be a useful thing for them to engage with, and you can always just not read it.

Also, we don't censor words here.

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

refseek.com

www.worldcat.org/

link.springer.com

http://bioline.org.br/

repec.org

science.gov

pdfdrive.com

318K notes

·

View notes

Text

Unusual but sympathetic paper:

Language Matters: What Not to Say to Patients with Long COVID, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, and Other Complex Chronic Disorders

https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/22/2/275

11K notes

·

View notes