Spanish Teacher from Mexico City. I write about language learning

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Spanish Imperfect Tense

The imperfect past tense of indicative is one of the verb tenses that can be most difficult for learners of Spanish when they are not native speakers of a Romance language such as French or Italian. In particular, the difficulty lies in differentiating it from the preterite (indefinido). Today we will look at some ways of understanding it.

1. The tree

This proposal comes from the teacher Clara Urbano Lira, and consists in considering the difference between the indefinido and the imperfect as if it were a tree. When telling a story, we will use both verb tenses, but the indefinido will represent the trunk and the branches, the fundamental part of the story, while the imperfect will be something like the leaves and the fruits or flowers, the details that make the anecdote richer and more complex, but which do not really advance the plot.

For example: En 2008 entré (ind) a la universidad. Era (imp) un lugar muy grande y podía (imp) perderme fácilmente. Tuve (ind) muy buenos profesores, compañeros muy interesantes, y crecí (ind) mucho como persona. Había (imp) muchos árboles en el campus, y la biblioteca era (imp) muy bonita, pasaba (imp) mucho tiempo leyendo allí. En mi segundo año conocí (ind) a Ernesto y caí (ind) completamente enamorada. Era (imp) un chico muy inteligente y simpático. Nos volvimos (ind) novios y tras terminar nuestros estudios decidimos (ind) casarnos.

If you notice, all the sentences with the imperfect add details, but we could take them out and we would still tell a story with the indefinido sentences: a very simple story, but one that moves forward in the end.

2. The imperfect is a present in the past.

In an article aimed at teachers, Ruiz Campillo explains that the preterite imperfect is a present in the past. This sounds like Zen wisdom, a kohan that seems illogical but which, if we let it dwell in our minds for a moment, will finally make sense. In fact, the indefinido is a kind of past-past, the action is finished, done, gone. The imperfect is a bit more complex, because it is obviously also a finished action, since it is happening in the past, but it is at the same time a kind of afterlife. In the imperfect, the action can live again, as if we were necromancers. It is as if it wasn’t finished yet, it is a finished action that is still happening, a present in the past. Crazy. Perhaps this will become clearer in the next point.

3. The projection on the wall.

I remember in my first classes as a Spanish teacher, when my students kept asking me about the meaning of the imperfect, I would resort to a metaphor that I came up with one day: that using the imperfect was like projecting a film on the wall. When we use the indefinido, it is as if we were transmitting information only, in a sense there is no narrative, it is just a chain of events, the script of the plot. In the imperfect, on the contrary, we make the film appear, the actions last, they are not finished yet, we see them live again. That is why the imperfect is a present in the past, it is a film that we can always play again.

4. Intuition

Now, and this goes for all grammar explanations: there is no problem with reading or reviewing a grammar text once in a while, for a few minutes, but don’t rely too much on them or ask them to do something they don’t have the power to do. True mastery of the imperfect, like any other element of the language, is going to come from experience, exposure. It is not as if after reading this article you will use the imperfect correctly on every occasion, that will come with practice. Little by little an intuition is generated in the student, a Sprachgefühl, which is the best tool in languages. However, a quick explanation, as this one was intended to be, can be a little push, a floatie to learn how to swim.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Misunderstanding, Making Mistakes: No Problem.

I never really studied English. It was just something that happened. I listened to music, watched MTV, spent time on the internet, watched Anglo series and films. Little by little I assimilated the language, just enjoying things that interested me. However, it wasn’t a clean and straightforward process, I realize now that I misunderstood some things, I guessed, I surmised, I invented.

For example, one of my favorite songs as a teenager was Kashmir’s ‘Surfing the Warm Industry’. In the song there is a verse that goes ‘It’s up to you cause I’m absolutely numb’. When I was thirteen I took that as ‘It’s your fault I’m insensitive’ rather than ‘You deal with it because I don’t care’. It wasn’t until a few years ago, when I listened to the song again, that I realized my mistake.

I’m sure there must have been dozens, if not hundreds, of similar mistakes. But they never ruined my enjoyment of English, nor — in the medium and long term — my learning. To notice my mistake I didn’t have to take a test or ask a tutor for help, it was a process of self-correction, without effort, without stress. Sure: it happened ten or fifteen years later, but only because I had not listened to that song again. If Kashmir had remained on my list, the correction would have happened much earlier.

What I’m trying to say is that we shouldn’t worry so much about making mistakes, either in production or comprehension, nor, much worse, about correcting ourselves. Self-correction will happen by itself, naturally, easily. When we are in the first levels of a language we should not waste time trying to find out if we are understanding completely and accurately. Rather than spending a week studying the lyrics of a single Kashmir song, it is better to read seven lyrics. Rather than spending an hour analyzing a single sentence, read a hundred sentences in that time.

This implies trusting that language learning is a long process. But then, it is also a smooth, fluid one. One fine day, I don’t remember when it was, I realized I knew English, I could understand it and speak it, and I didn’t know how it happened, I didn’t remember putting an ounce of effort into it, I’d never opened a textbook, never studied in the evenings. I just did what I wanted, listened, read, watched, and one day the job was done.

Beyond some embarrassment -which fortunately never happened-, such as being exposed by a classmate more proficient in English and rock, what were the consequences of misunderstanding that Kashmir verse? It would have been more damaging to dwell on it, to dwell on every verse of every song I listened to, instead of having that more general, more casual approach, where hundreds, thousands of words came my way. A language is a self-referential system, organically self-correcting, like an AI as it receives more input. I misunderstood that verse, in my early attempts at English, but as I continued to delve deeper into the language, correction would be assured later on.

I have seen many students get frustrated by the number of mistakes they make, in speaking and understanding, struggling to catch every tiny detail, every little word. This is unnecessary stress. They are stopping too long, they are using a magnifying glass, a microscope, on a cross-country trek. Self-correction is going to come one day, effortless, easy, obvious. And by the time it comes, instead of having spent hours and hours of arduous and boring time, we will have just walked through a beautiful landscape.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Clear and Holistic Explanation of the Subjunctive Mood: Non-Statement

Conventionally, the subjunctive mood is taught according to a case-by-case logic (by means of triggers such as No creo que/Es + adjetivo + que) or, when the aim is to give a comprehensive grip, one resorts to formulations of the type “The subjunctive is used to express desires, personal opinions, unreality”. The problem with studying the subjunctive case by case is that it can become overwhelming, too many triggers to memorize, you end up with quite a long list of situations in which you need it, and if you add to that your other lists of verbs, nouns, etc., learning Spanish resembles data analysis. The issue with the second explanation is that it is simply not correct: wishes, opinions and unreal or hypothetical situations can also be expressed in the indicative mood. Students who follow this route end up making sentences that are quite original, but not really natural. Luckily, the Spanish scholar José Ruiz Campillo has given us another alternative, which in my experience is bulletproof: the subjunctive as a non-statement.

Indicative vs subjunctive

Let us begin by distinguishing the subjunctive from its “arch enemy”, the indicative. Both are moods that contain different verb tenses. That is, both the indicative and the subjunctive have their present, past, future and so on. Yo soy is a present indicative, yo sea is a present subjunctive. Now, what is important for this topic is that while the indicative states, says what things are, ventures, takes risks, the subjunctive does not state, it allows itself to participate in the discussion, to mention things, to refer to them, but never puts its neck on the line, never says what it is or is not, it refrains from doing so. This will make sense later on.

Ella es o ella sea

An example given by Ruiz Campillo is really useful to understand what is at stake between the indicative and the subjunctive. Suppose we have a friend in common, Margarita, and we are talking about her. Unbeknownst to us, Margarita has walked past us and heard us say …Margarita es tonta… (indicative). In this case, our friend has every right to be annoyed, because no matter what came before or after those three words, the fact remains that someone is declaring her to be dumb. But now suppose she walks past us and hears …Margarita sea tonta… (subjunctive), in this case our friend doesn’t have much to complain about, because everything that can complete that sentence is a non-statement, for example: no creo que Margarita sea tonta/es una mentira que Margarita sea tonta, etc. So, in our conversation we have touched on the subject of “Margarita ser tonta”, yet we have not pronounced ourselves in favour of this idea; we are commenting on it, but we are not confirming it. That is the meaning of the subjunctive, which can refer to things and situations, without this implying that we are stating that they are so.

Subjunctive of desire

A common structure (a trigger) to express wishes is Yo quiero que/Me gustaría que/Espero que or the impersonal Ojalá que. In all these cases the subjunctive is needed for the second part of the sentence Ojalá que llegues bien a tu casa/Espero que te vaya bien mañana/Yo quiero que todos vivamos en paz. Why? Because if we were to make a statement in the second part, we would be doing something rather odd: wishing for something we already have. “Ojalá que llegas bien a casa” (indicative) is a contradictory sentence, because at the same time that I wish for you to get home safely, I am in fact stating that you have already arrived. Why wish for something that we already have or that has already happened? Of course, this difference is specific to Spanish and other Romance languages, and it loses its meaning completely if applied to English or other languages, so instead of translating, try to stay within the logic of Spanish.

Subjunctive of questioning

Another common trigger are sentences that begin with No creo/No pienso/No considero. Here we are basically announcing that what is coming, the second part, is something we don’t want to state. In fact, that we are countering someone else’s statement. No creo que sea buena idea/No pienso que tengas razón. The subjunctive should be used here because we cannot question a piece of information/statement, and then go on to state it. No creo que es buena idea (indicative) is a contradictory sentence because at the beginning we are being critical and then we finish off with that same statement we want to oppose, affirming what we are questioning, a nonsense.

Subjunctive of non-identification

Now a case in which the decision to use the subjunctive or the indicative modifies quite a lot what we want to say. If we go into a shop and say Estoy buscando una mochila que es roja, with the indicative, we are implying that we already know what model we are looking for, perhaps we saw it online, or in the shop window, but we know that this specific red backpack exists, it is something particular and different. If we go into the shop and say, instead, Estoy buscando una mochila que sea roja, with the subjunctive, we imply that we are not thinking of any particular backpack, that we are looking for any backpack, with the only condition that it is red. Similarly, if we are in a public place and we say to a stranger Estoy buscando a una persona que tiene el pelo azul (indicative), it is understood that we already know this person, that we know he/she exists and is a specific friend we lost and are looking for. If we say, on the other hand, Estoy buscando a una persona que tenga el pelo azul (subjunctive) something very different happens, we are saying that we do not know this person, even: that we are not even thinking of a specific person, it is just that we are looking for any person who meets this trait.

Subjunctive of valuation

A much more subtle case, which really tests the explanation of the subjunctive as a non-statement, is what happens in sentences with the structure of Es + adjetivo + que, such as Es molesto que tú no me entiendas/Es horrible que me hables así (…these are not autobiographical examples…). Here, if for the second part we were to use an indicative no me entiendes/me hablas, we would be committing an error which has to do with the different weights or importance between the subjunctive and the indicative. The indicative is strong, it declares, it weighs, it has the spotlight. The subjunctive is weaker, it mentions, it is lighter, it stays quiet. When in a sentence with this structure we use two indicatives, it is not clear which is the important one, which one is the message we really want to give. Es bonito que estamos juntos (both indicative) is a somewhat defective sentence because it contains two statements, es bonito and estamos juntos, and it is not easy to tell which is the one we are interested in emphasising. It is not a serious mistake, and probably many natives have made similar sentences during their lifetime, yet it is a somewhat weak sentence, poorly built: both statements weigh the same, but although they seem similar they are saying in fact very different things. On the other hand, Es bonito que estemos juntos (subjunctive) puts all the spotlight, all the importance, on that first statement es bonito (indicative) and the part of estar juntos is less strong, because it is obvious, because we take it for granted, because we know we are together and it is not necessary to state it again, what I am interested in stating, communicating, highlighting, is that this, being together, es bonito, and so I give all the spotlight to it.

There are still more cases of the subjunctive than the ones we saw in this article, but the next time you come across one you can do that test, ask yourself why is it a non-statement, why is that subjunctive there instead of an indicative, what would happen if we changed from one mood to the other.

Of course, mastery and correctness depend a lot on intuition, and intuition in turn depends on practice, on experience, so don’t try too hard to master the subjunctive after reading this article, it is a process that will happen in time, once you have seen enough wild subjunctives in nature (in context). However, the idea of the subjunctive as a non-statement can help you to digest this subject better, to find some ground, some compass, above all: to know that there is a logic behind the subjunctive, a raison d’être, and that little by little you will be able to understand and use it.

You can also go to Tercera Gramática, Ruiz Campillo’s website for Spanish learners.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Choose Simple Sentences to Start Conversing

Regarding production at beginner levels, there seem to be at least two types of learners: those who have a hard time speaking, who are silent or hesitate at every word they utter, and those who jump right in from the start as if they were masters of the language, as if they didn’t notice their flaws or didn’t care. One of the main differences is less fear of making “mistakes”, but there may also be another issue, a tendency to want to make long, perfect sentences in the former, and conformity with short, simple sentences in the latter.

My German teacher could tell when I had a long, elegant, ambitious Spanish sentence in my head, and she could see in my face the efforts I was making to translate it into German. It is not recommended to translate while speaking (production should be something more spontaneous) for various reasons that we will see in another article, but in this case it should be emphasized that it is a very difficult task, very improbable, to render a sentence from a native level Spanish to a B1 German. My teacher, seeing me suffer, suggested that I make a simpler sentence, with what I could, in German. What I wanted to say, the core of that message, I could say sufficiently with my knowledge, with my rudimentary level, if I just focused on how to express the essential: an economy of meaning.

I must apologize, but here is another sports metaphor. It is common in Mexico to hear coaches or one’s own teammates shout “Make it easy!” after someone attempted a risky pass, which was going to have many consequences but only ended in a turnover, in a failure of the offense. Make it easy means make the easy pass, not the tricky one. Sometimes it is necessary to first connect short, quick, simple passes (phrases) that build a volume of play (a conversation), instead of trying very daring ones (long and complex phrases) that will only end up in the hands of the opponent (in a confused and stumbling communication).

What my teacher was asking me to do was just that: make it easy. I had a better phrase in my head, in Spanish, but I could say something similar, something that worked, with my knowledge in German in simpler sentences. Maybe my language would be less impressive, but the conversation would be more fluid, I would receive faster and more responses from my interlocutor, that is, I would have more input, more learning. Over time my sentences would improve, would grow, but from German, without going through Spanish structures, without translating, and by that point I would already have a long history of successful (simple) conversations. A natural and patient evolution.

The most important thing in a conversation, as well as in a language class, is that communication is established. “Mistakes” are only really important when they are affecting meaning, when messages are lost or distorted. The other type of errors, those of refinement, are secondary and can be worked out over time. As long as there is a conversation, an exchange, a back and forth of messages, everything is going well, there is volume of play, there is enjoyment, there is mastery.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Two Key Exercises for Learning a Language

I’ve heard several times that the only exercises we need to be fit are three: the squat, the pull-up and the push-up. Sure, many other types of exercise are also useful, healthy, and perhaps more fun and challenging, and it’s fine to have a varied routine or full of the activities you enjoy most, but the fact is that those three exercises already work the muscles we need to have a strong body, and that a person who only does those three can feel confident that he or she will make progress.

I think something similar happens in language learning. There can be a lot of choices in terms of methods, materials, techniques, etc., but at the end of the day it’s two activities that are going to bring the most progress: reading and listening. If we are doing those two things, our squat/push-up/pull-up, we can rest assured that over time we will get better. There are options that seem more appealing, or more modern, or more complex, but reading and listening should be the foundation of a learning program.

This is not to say that other methods such as flashcards, vocabulary lists, working on our own production (writing, or recording ourselves speaking), studying grammar, using apps, etc., is not to say that all of these things are useless or counterproductive (although Stephen Krashen seems to say so at times), but it raises the question of whether we might be basing our learning only on these activities that have an ancillary nature (something like just training cardio or just doing bicep curls) and whether we might not also need to work on those basic, encompassing movements, interacting with real blocks of language.

Additionally, many of the different methods or techniques for studying a language can be thought of as just variations, in many cases, of those two basic movements of reading and listening (just as many exercises are variations of push-up/squat/pull-up). For example, progress can come from an app like Duolingo because ultimately we are doing just that, reading and listening, but maybe in a very unnatural and unintensive version (think of those exercise machines that try to be innovative and end up being a trinket). Sometimes these methods focus on working a certain specific part instead of working in a more holistic way, but just as using only focused exercises can give us an unharmonious body, concentrating on studying certain specific things can give us a misaligned and out of proportion level, with gaps, the most typical case being students who understand the grammar of the target language almost completely, but cannot produce sentences naturally. Reading and listening ensure balanced and comprehensive progress.

Enjoyment should be a compass in any learning process, so if you like other kinds of activities there is no problem in continuing to practice with them, but it is always worth getting down on the floor and doing push-ups, that is, reading a novel. It seems more basic, more simplistic, but just as doing ten pull-ups is no joke, finishing a five hundred page novel is not either, and in both cases the progress will be easy to notice and feel.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Interest in the Culture

One factor that can determine how quickly a learner progresses in a language, or even whether or not he or she will ultimately succeed in mastering it, is the interest he or she has in the culture related to it. That is, if a learner of Chinese is interested in Chinese culture, a learner of Korean is interested in Korean culture, and so on. Beyond study techniques, beyond personal aptitude, I believe that the degree of this kind of interest in a student can be the key to his or her progress.

When I was in high school, my school divided my generation into an “advanced” English class and a “basic” English class. I had friends in both groups, and when I think about the difference between them, between the friends who could speak English and those who struggled with it painfully, I find the reason. The friends who struggled with it lived immersed in Mexican culture and those who could speak English tended to be fans of Anglo bands, watch Hollywood movies and series with subtitles, had an important contact with Anglo culture. For them, learning English was a pleasant consequence of spending time with objects they liked. For the former, on the contrary, English was always a struggle and a torture.

This has to do, of course, with the theory of comprehensible input, that progress in a language comes from reading and listening, the reception of content. Interest in a foreign culture is an obvious determinant of how much time someone will spend with the objects of that world, how intensely they will surround themselves with them, until they build up an artificial immersion (to differentiate it from traditional immersion: traveling to the target country). And it works the other way around, when someone decides to (or is forced to) learn a language, but has little or zero interest in the culture of that language, we can bet that their learning process is going to be slow, arduous, and probably destined to fail.

Even in intermediate-advanced learners, lack of interest in the culture is going to hold them back at some point. They may lack certain turns of phrase, idiomatic expressions, slang, intonation, and the rhythm with which a language should be spoken. Probably the degree of interest is going to predict how close to native-like their pronunciation can be. Pronouncing well, speaking a foreign language well, is something that requires acting skills. When we speak another language, we are others, in a sense, and that performance will depend on our knowledge and love for that culture, to what extent we are willing to venture into it, to imitate it. To sound almost native you need to be almost native.

One can see how cultures like Anglo or French, with a high international prestige (we are not going to discuss Eurocentrism here!), often get students who fine tune every last detail, who try to sound as much like the natives, to use the same words, the same sayings, who are really striving to be part of that other culture that interests them so much and that surrounds them and runs through them.

If you are really interested in the culture of a language or, better yet, if that is the reason why you are learning the language, you don’t need much advice, chances are that your interest, your approach to the objects, the people, the manifestations of the language, will sooner or later lead to fluency. But if the opposite happens to you, if you are learning a language for other reasons, for work or necessity (it’s valid!), perhaps it would be a good idea to try to get to know the culture, to try to find something admirable, interesting, exciting in it. There is no culture that isn’t. This will make your learning process easier and more enjoyable, and the target culture will become part of your life: an intense adventure.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comprehensible Input VII: Conclusion

This is the end of this series on comprehensible input theory, and perhaps it has already become too long, but I wanted to close on a more personal note, explaining again why it is important to me, why I think these ideas can be so beneficial to learners (and teachers).

It is very sad to see a person give up and abandon their goal of learning a language. There are many reasons why that can happen, but a usual culprit is not having an alternative to the traditional grammar-based, drill-based, textbook-based model, which can be either difficult, boring, or both. Enjoyment should be the compass in language learning, and not all people (there are those who do) have a good time with these materials and strategies.

I learned (like many in my generation) English without realizing it — one of the benefits of living in the atmosphere of the United States — there was never a moment of formal study, of purpose, of deliberation. I was simply enjoying things I liked: music, movies, websites, struggling to understand the language not in order to “know English” but to be able to approach the information or works that interested me. My knowledge of the language was gradual, progressive, and almost effortless. It felt like it happened by itself, a photosynthesis. Everything we saw in this series, the whole theory of comprehensible input, explained to me my own experience.

Often language learning is thought of as something you have to do before you can tap into the culture or communicate with native speakers. An important element of Krashen’s ideas is that you don’t have to wait, you don’t have to graduate. You may have to start with children’s books, with simple materials, but you are in fact already interacting with the real language, and not with a simulacrum or an artificial version (as happens in the exercises of a traditional course). In other words, if you want to learn English in order to understand Kurt Cobain, all you have to do is read Nirvana lyrics (that’s what I did when I was twelve years old).

That learning while doing, daring to interact with compelling cultural objects, the reminder that interest and enjoyment should be the foundations of your process, is what I find so valuable about Krashen’s ideas. This series has been a theoretical journey, but it has a simpler message: surround yourself with a language, its objects and manifestations, and you will end up learning it, no doubt about it.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comprehensible Input 6: Monitor Theory and Affective Filter

I frequently get new students who come from a process of a lot of grammar. Perhaps they have studied at school or at a language institute, or they have completed a Babbel course (an app I am very fond of) or read a textbook; all the same, the result is that they have a correct knowledge of the basic rules of Spanish. The problem is that this does not necessarily increase their ability to speak or understand me, and many times it even seems to be a hindrance.

These students can suffer from a paralyzing hesitation that makes our communication stumbling, arduous. They happen to be doing two things at once: producing and analyzing what they produce, or worse, analyzing before and after they express themselves. The RAM of their brain is stretched to the maximum. Sometimes those who have not studied much grammar pronounce rather incorrect sentences, but they can be quicker and more direct, which promotes lively conversation and more opportunities to receive the teacher’s input.

Learning (grammar) generates a creature called monitor, a kind of inner policeman who checks the sentences you produce or are about to produce. It is a useful tool because it allows us to take care of form, correctness, and to direct our process in a certain way, but it should be restricted to certain moments — solitude — when we have enough time to think, write, correct, talk to ourselves. Using the monitor in real time conversations can be detrimental, it slows us down, makes us insecure, makes us lose the thread of the conversation, pay less attention to the interlocutor (because while he/she is talking we are preparing sentences in our head).

Making use of the monitor in conversation is related to the fear of making mistakes, the desire to have a correct speech, but this aim for perfection damages communication much more than mistakes (which are an inevitable part of any learning process), and can very easily grow to become a real problem: insecurity, shyness, frustration. When the student has these negative emotions, the assimilation of input becomes more difficult, more arid, and all progress is put in jeopardy.

Another pillar of the theory of comprehensible input, the last one we will look at in this series, is the affective filter. When the learner feels frustration, fear, or any negative emotion, he “raises” his affective filter, it is a barrier, the language has a lot of trouble getting through it. The student shuts down, does not listen, attacks himself, loses confidence, and probably abandons his goals.

That is the danger of studying too much grammar and depending on the monitor. To pretend to use it to reach a perfect production is an enterprise destined to fail, mistakes are inevitable in a language learner, at some point they are going to happen. Error-free (or nearly error-free) speech is the result of years of interaction with the language, but all those years are going to be riddled with imperfections, and that’s okay! Even native speakers make “mistakes” from time to time.

It’s better not to worry, to let our production come out without constantly monitoring it, without attacking ourselves, let it come out as it is, and engage in real, interesting, fun conversations. Have a good time with the language, make it an enjoyable process. This is the responsibility of the student but also of the teacher; sometimes, more than the explanation of grammar rules and their guidance and knowledge, what is most required of him or her is to build in the classroom a positive, engaging, cheerful environment, where students feel safe and lose the terror of making a mistake, where language becomes a party.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

¿Por qué la gente decide estudiar español? Como hablante nativa tengo curiosidad de forma genuina.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comprehensible Input V: Natural Order

Closely related to the difference between learning and acquisition, the comprehensible input hypothesis also advances the idea that there is a natural order in which the elements or structures of a language are acquired. This order does not really vary among learners and cannot be altered by the teacher or the learner himself. Over time anyone can master all the pieces and mechanisms of a language, but this is going to be a gradual, progressive process, one that must be trusted, and one that we cannot overtake or modify.

That is to say, a certain grammatical topic, for example the subjunctive of Romance languages, the declensions in German, or even things like using the correct prepositions, are issues that cannot be assimilated, let’s exaggerate, in the first month of study. No matter how much effort and hard work, a beginner is not going to be able to master a given advanced grammar topic if he or she has not yet mastered the previous ones. The process goes from the general to the particular, from the fundamental to the last details.

As we have seen in this series of articles, the mastery or assimilation of the elements of a language will come from the interaction with it, from the reception of content (messages). Thus, not only will grammatical structures be assimilated intuitively through comprehensible input, but, if we accept the idea of natural order, this assimilation will also follow a pre-established progression, with very few variations, to which it is better to surrender rather than fight it.

In practical terms this means that it is not worth martyring ourselves for mastering a specific grammar topic with which we have been struggling. That difficulty may come from the fact that it is not yet time for us to assimilate that topic or structure. Many times my students ask me to work on something in particular (almost always, the infamous subjunctive), and I accept and give certain explanations or conduct certain exercises (trying not to take too much time away from our precious conversations or readings), but in the end I always try to recommend patience and a healthy “don’t stress, don’t worry, you just keep reading and listening; the time for the subjunctive will come, it will come.”

In this way the disadvantages of organizing a learning process around grammar topics become visible, because the student may not yet be ready for the topic at hand, and that formal study is going to have little or no effect: he will learn rules for things he cannot yet use. Having said that, a five or ten minute grammar explanation can clarify things and speed up the process, but this should be after the moment a student starts to produce or at least notice a certain element of a language, and not before that as a preparation. The idea would be that it is not the study of a grammar topic that prepares us for it, but that once we are already hands on, producing or clearly perceiving that topic, is that an explanation can help us better understand what we are in fact already doing.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comprehensible Input IV: Learning and Acquisition

Another of the fundamental points of Stephen Krashen’s comprehensible input hypothesis is the difference between learning* (the formal study and memorization of grammatical rules and other structural issues of a language) and acquisition (the intuitive and gradual assimilation of the language). This is one of the features that separates it most from traditional methods of teaching a language, which tend to prefer learning and think that mastery will come from that, whereas Krashen would respond that the benefits of this are rather secondary, and that the real progress comes from the learner’s mere interaction with the language, and that, in a course designed around learning, it is not as intensive as it might be in other strategies.

Learning is actually what is done in the vast majority of language courses, books and apps. Grammar topics are explained, exercises are designed to employ those rules, quizzes, it also includes the use of vocabulary lists, flashcards, memorizing triggers, etc. Acquisition is what is going on behind the scenes, the words that the learner is adding to his vocabulary and can understand and use effortlessly, the sentence structures that come out of his mouth automatically and easily, the development of a certain intuition and rhythm: Sprachgefühl.

There is a clear difference between these two dimensions, and confusing them can lead to frustration and doubt in learners. It is one thing to study the rules of the subjunctive and quite another to assimilate its use and be able to produce or understand it when it appears in a text or conversation. The idea of courses based on the formal study of grammar is to assume that this study will lead to mastery. In other words, it is traditionally considered that learning is what fosters acquisition, that the way to be able to understand and produce a certain grammatical structure is to study the topic to which it belongs, to see the explanatory table, to do exercises, to review it from time to time; in short, that the study of a grammar topic is equivalent to its mastery. This way of looking at things is a bit suspicious.

I think of my history with German, a language I studied for five years with a special emphasis on the study of grammar rules. At a certain stage I was able to remember many rules, to the point that I could see the mechanism of the language in its, I think, almost totality. But it was a very different thing to be able to employ all that correctness when speaking. I still remember the endless times when my teacher would show me two fingers to remind me of the Position II of the verb, which I had just messed up.

It so happened that although I had studied many grammatical rules and could understand them and even recite them by heart, I had not really assimilated them. I knew perfectly well, and if they asked me in an exam I would answer it correctly every time, that the Position II of the verb had to be respected, and yet every time I spoke I could not produce it, it was simply not in me. I knew the rule but I did not have assimilated it.

A very different case was my experience with English, a language I learned through audio-visual content, books, music, and of which, even until now, I know very little about its rules and grammatical structures. However, after Spanish, it is the language I have mastered the most, to the point that understanding and producing it is something natural and simple for me. It is because all those grammatical rules, which are operating in the content with which I interacted, were deposited in me, sedimented, like following the rhythm of a percussion, and little by little, without the need to study them formally, they became an intuitive and secure part of my English.

If you think about it, what percentage of native speakers know and can explain the grammatical rules of their own language, and why those who can’t, nevertheless are able to speak and understand it perfectly well?

*I think it is a bit confusing to use the term learning, because it is too general. I would have preferred formal study or something along those lines.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

El ensayo amable

"Ensayismo, de Brian Dillon... es un libro encantador, inteligente, bien escrito, razonable, argumentado, seductor, lúcido, documentado, elegante, es decir, absolutamente hueco. (...) el ensayo, cuando es interesante, es ante todo un texto de combate. Una máquina de guerra contra las convenciones, el sentido común (en especial el sentido común progresista), un texto que derriba, que impone un nuevo orden sobre las cosas." Damián Tabarovsky ���

https://www.perfil.com/noticias/columnistas/el-ensayo-amable.phtml

1 note

·

View note

Text

Comprehensible Input III: The Role of Output

In the last article we saw the foundation: input. Now it is time to think about the place of output. The first thing to state is that in the output there is no learning. That is to say, no new knowledge comes from the student’s own production. This, if you look at it carefully, is quite evident, the production is only the deployment of the knowledge already acquired, you cannot produce what you do not know how to produce. Our brain, when it comes to language study at least, is like a sausage machine. You have to put something in it to get something out; what comes out is in direct relation to what goes in.

Understanding this from the start can save us from inefficient strategies. There are many learners who, frustrated with the state of their target language, decide to redouble their efforts in production activities, write more, speak more, but that’s just going to be repeating over and over again what they already can and already know. If you want to advance in a language, you need to introduce new things: reading, listening. Spending time producing, and expecting new vocabulary, new phrases to come, is asking for pears from an elm tree. At best, what may come is veteranism.

I remember a student once told me that his strategy for practicing was to record himself speaking Spanish and then listen to it. This activity can be used to detect errors, especially in pronunciation, and in a general sense it serves to become aware of one’s own production. Also, in principle I approve of any activity that is enjoyable; although I am not a big believer in them, I tell my students that if they enjoy using flash cards, textbooks, vocabulary lists or conjugation tables, go for it! Enjoyment is the best way to learn a language, because it makes it easier to persevere.

However, there was a limit to the activity my student was engaged in; considerable progress could not be expected from it. Perhaps it could bring progress in self-correction, but the advancement in terms of the vocabulary of a language (which is, perhaps, the most important thing) was really zero, because the student was only reviewing words he already knew. It would have been much better to spend the time on activities that provide new vocabulary, i.e., and this refrain needs to be tattooed on the head, reading and listening.

The only role that output plays in vocabulary acquisition, according to Krashen, is to be a trigger for the interlocutor’s input. In a conversation, our own response will elicit a new response from the interlocutor. If we remain silent, the interaction will probably end, but if we continue to ask questions, to participate, the talk becomes longer and the interlocutor gives us input again and again. This is why it can give the impression that, just by daring to speak, our production improves, and for this reason people who lose their shyness and seek out opportunities to interact with native speakers tend to improve more quickly. But it is not their own production that deserves the credit, but rather the eliciting of input from other sources.

You can support my work and get language coaching here.

You can also take a lesson with me on Verbling or on iTalki.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comprehensible Input II: Where Progress Happens

I believe that the center, the node of the comprehensible input hypothesis can be summarized as follows: the only moment of learning is when the student receives and understands a message. That’s where it all hinges.

When I think back to my first years as a language teacher and student, and to my time in the diploma program for Spanish teachers at UNAM, before I became acquainted with Krashen’s work, I have the notion that there were three main conceptions floating in the air about how a language is learned. The first, grammatical, thinks that a language is above all a series of rules, and that once the student knows them he can also understand and express herself, that is to say, that knowing the rules of the game is equivalent to being good at it.

A second was to view learning according to the division between passive and active, and oral and written skills, as distinct dimensions of a language, as if reading/writing and listening/speaking were interrelated but ultimately separate competencies, and thus progress in them was an autonomous matter. So that to improve writing one had to write, to improve speaking one had to speak, etc. Practice makes perfect. This conception has some things in common with the input hypothesis, but the huge difference is that the latter views writing and speaking as consequences of reading and listening, not as skills to be developed on their own, so that putting too much effort into them is an unnecessary waste of energy and time.

A third, somewhat related to the previous ones, consists in the idea of memorization. As if a language were just a set of words to be memorized by force. This is the origin of lists of verbs, lists of nouns, vocabularies focused on different topics, and so on. Of course, for the input hypothesis there is also a component of memorization of words, of acquisition or assimilation of vocabulary. The big difference is that where the former idea relies on willpower and on separating words from their real contexts (putting them in a list), the input hypothesis considers that the best way to learn words is organic, progressive, always interacting with them in real and meaningful contexts.

What makes the input hypothesis different is its assertion that in speaking and writing there is no learning, that learning happens at the moment of receiving messages, decoding them, understanding them; as well as the idea that grammar is learned intuitively, without the need to study explicit rules. It is as simple as looking at a picture of an apple and reading the characters that form the word apple. There is an understanding of the message, and there, and at no other time, is there learning. More complex sentences, longer messages, actually just repeat the same operation.

This is why the input hypothesis recommends a learning program based on the reception of messages, that is, on reading and listening. Of course, the word “comprehensible” is also very important. It does not do much good to throw a Heidegger book at the student in his first week with German. The key, and this is one of the functions of a tutor although the student must also take matters into his own hands, is to look for materials that are challenging enough to stimulate progress, but simple enough to be, with some effort, understood.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

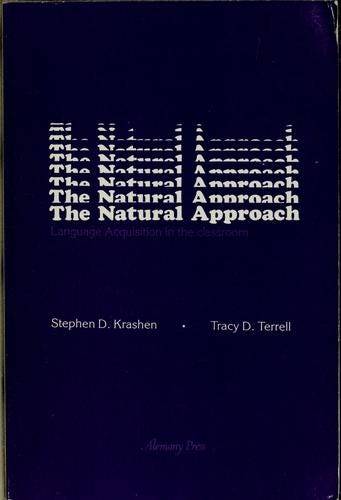

Comprehensible Input: introduction

In the midst of the pandemic, in 2020, I had a trial class with a new student, James. In the interview he told me that he didn’t want to study grammar or do homework, nor any exercises. Since he was a total beginner, I thought it was quite difficult what he was asking me to do, and that he would make minimal progress. He gave me a link to a video explaining the method he wanted to use in our classes. A bit skeptical, I watched it. We had not seen this theory in the teacher’s training. It was my first contact with the natural approach, or comprehensible-input, or input-based learning.

Before that, my teaching had been based on grammar and communication tasks. I used a textbook (Dicho y hecho, from UNAM), a grammar website (Lingolia), tried to follow a clear progression in topics, and saw in-class conversation only as practice or even a break. After watching James’ video, I understood that the natural approach had been the way I, and so many people of my generation, learned English: through movies, series, music, video games, websites, just interacting with the language, trying to decipher it, to go through it to get to the information we were interested in. I spent my life receiving messages in English without trying to produce them, but little by little my oral and written expression improved, effortlessly. The comprehensible input hypothesis, pioneered by Stephen Krashen, explained why. It was a total change of perspective.

In brief, what the input hypothesis proposes, in a microscopic vision, is that the only true moment of learning is when the student receives a message (encoded) and understands it (decodes it), that it is only through this process of reception that the structures and contents of the target language are assimilated, take shape in the student’s mind, and gradually become resources available for production. Thus, it is not advisable to study grammar or do exercises, but rather to focus on “passive” tasks such as reading and listening, trusting that speaking and writing will be the consequences of this.

Therefore, a study program based on comprehensible input would replace textbooks with novels, grammar charts with magazine articles, drills with real conversations, the need to memorize the basics with a dive into the language, jumping into the pool without knowing how to swim. It is, in a sense, a method without a method, a Zen method, learning the language by interacting with it, as if you already knew it, a kind of learning by doing, learning on the job. Of course, trying to mark a trajectory that goes from the simplest content (books for babies and children, for example) to the most complex.

In my experience, viewing language learning in this way generates a less stressful, less forceful study, and more fun and interesting. Personally, I think a little grammar can be useful at different times, but I generally subscribe to the ideas of Stephen Krashen and company. In the following weeks we will look at the basics of the input hypothesis in detail.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Production and readiness

We have mentioned how the real moment of learning, from the perspective of the input hypothesis, resides in the comprehension of messages (reading, listening). Production (speaking, writing) is only the implementation of what we already know and can do. Probably the only contribution of production to learning is, when we engage in conversation, to provoke a flow of input to us: the interlocutor’s messages. However, I do believe that the practice of production generates its own progress, but that it is not about achieving more vocabulary or new sentence structures, it is about achieving a feeling, a state of mind: readiness.*

Suppose a person, a faithful believer in the benefits of comprehensible input, has spent two or three years reading and listening to a language, now understands it very well, and when she is with herself can produce simple sentences fluently. However, she has never spoken to any native speakers of the target language, nor has she ever written any emails or messages. In that sense, she is still a rookie. Her command of the language may put her in a better or worse position, but I think her first encounters with native speakers are inevitably going to have a fair share of nerves and insecurity. These are the first tests.

From time to time I explain to my students that they could think of their time alone, their daily language practice, as training, as if they were an athlete preparing. It is in that daily exercise, in reading and listening, that their vocabulary and grammatical intuition grow. The time we spend together, our hour-long conversation, can be seen as the match (without competing!), the time to put their skills into play.

When you’ve had enough conversations in the second language a certain trust begins to emerge in you. You are confident in your command, you can stop thinking and analyzing yourself, you know you will solve the communicative situations that occur. Students who have played many games, who accumulate hours and hours of conversation or writing, “se foguean”, as we say in Mexico: they go through fire. Nothing can disturb them anymore. It is not that in our lessons they have learned vocabulary and grammar from their own production (except for provoking my input), but when they deploy it they see themselves doing it, being capable, sustaining a communication: they learn the trade.

That is if they have not been too critical of their production, attacking it with rules and doubts and constant self-corrections. This is dangerous because instead of generating the tranquility of seasoned experience, it causes self-doubts and discouragement (like an athlete on a losing streak). Therefore, I think it is important to emphasize that knowledge happens in comprehension and that production is only a consequence. When you start speaking there is nothing you can do, the state of the language is what it is, and it is better to relax and put it to the test, for pleasure, to see where it is, to see where all that work of comprehension done during the week has gotten to. Pleasant surprises can occur.

The moment of production is not the time to learn or improve it. This is equivalent to doing two things at the same time: speaking (concentrating on the conversation) and analyzing oneself, correcting oneself, paying attention to one’s own sentences and not to those of the interlocutor. It is not worth stressing and attacking oneself for faults or doubts. It is better to enjoy our production, to see it unfold, to see it come out. It is no longer up to us, we can what we can, we play as we can play. Once the conversation is over it is possible to go back to individual work, to training, to prepare for the next game. But after a real conversation you’re on the way to confidence, you’re battle-scarred.

*The original text in Spanish uses the word veteranía, which could be translated as veteran-cy, veteran-ness.

1 note

·

View note

Text

All that is needed is attention

In a movement similar to that of input hypothesis, it seems to Weil that what precedes creation is reception, the brewing of things within, as if it were a pregnancy gestating, until finally comes a moment of output, of gift: “Writing is like giving birth: we cannot help but make the supreme effort.” “The poet produces the beautiful by fixing his attention on the real.” It is as if, before launching into writing, we should go through periods of silence and acceptance, let something grow inside. It is only at the end of that quiet gestation, that preparation, that something will come out of us and be worthwhile.

https://paper.wf/languagedaemon/all-that-is-needed-is-attention

2 notes

·

View notes