Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Grammatical cases in European languages

by amazing__maps

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

The spanish a that is not translated

So, there's this spanish particle, a, which is used when you refer to specific persons or beloved animals, as long as they are the direct object of the sentence. You don't need to translate it in english but... it's there.

For example, if you want to translate something like

"I can see Maria",

like I'm looking at her right now, you'd say

"Veo a María".

You can't express it without the a. The same goes for animals too. If you walk the dog, you

paseas al perro.

If you are not specific about that person, there's no need for the a.

For example, if you hate a painter (you have to know him in order to hate him, so he's a specific painter), you'd say

Odio a un pintor.

But if you need a painter, any painter, anyone would do the job for you, you´d say

Necesito un pintor.

No a needed in this case.

So, this is called the personal a. It is said that it comes from latin ad, a preposition meaning to, towards. It seems that it stuck to the spanish language in order to prevent ambiguity. What kind of ambiguity?

Let's say that Jorge sees María. So in spanish,

Jorge ve a María.

Since spanish word order allows the object to get to the beginning of the sentence, if there was no a there, it would be unclear who sees who. But since María has a personal a, it´s easy to deduce that it´s Jorge that does the... seeing. And if we were to change the order, it would still be clear:

A María ve Jorge.

A always follows the object.

So this a isn´t translated in english or modern greek. English has its word order to tackle such matters of ambiguity, whereas modern greek has its omnipotent declension system.

John sees Mary. (if it was the other way around, the sentence would begin with Mary). Ο Γιάννης βλέπει τη Μαρία. (Maria is in the accusative case, rendering her the object of the sentence.)

#spanish#language#greek#modern greek#alangblrofsorts#langblr#english#ελληνικά#personal a#accusative#word order#ambiguity

0 notes

Text

A tearful post

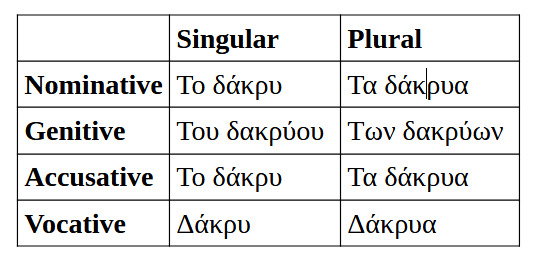

Δάκρυ is the modern greek word for tear, as in the tear one sheds, the spanish lágrima. It's neuter and the plural is δάκρυα. It's an ancient greek word we still use today. Here's its modern greek declension table.

Very important note: no-one uses the singular genitive. Ever. Though it can be used in scientific context (ie opthalmology), it sounds rather archaic and/or poetic, definately strange, wrong, eerie, makes you sound like a broken machine, etc. The same is true for all nouns of this declension group, but that's for another post. So when speaking greek, you have to avoid using δάκρυ in the singular genitive. There are all sorts of workarounds for that. The only reason it's on the table is for me to show that it exists. Other than that, don't use it. Just... don't. Please.

Btw, isn't it awesome that there's a special case to address everything in modern greek? I mean, vocative for tears? Why should anyone address a tear? Perhaps it's useful for poets but other than that... dunno...

So, from δάκρυ we get these derivatives:

δακρύζω: this is the verb for "well up", "tear up", shed a tear.

δακρυσμένος = this participle denotes someone who is tearful, in tears.

κροκοδείλια δάκρυα (only in the plural) = crocodile tears

δακρυγόνο (noun, neuter) = tear gas

Here are some examples:

Σκούπισε τα δάκρυά σου. (= Wipe your tears).

Όταν καθαρίζω κρεμμύδια δακρύζω. (= When I peel onions, I tear up).

Γ��ατί είσαι δακρυσμένος, Γιώργο; Τι συμβαίνει; (= Why are you in tears, George? What's wrong?)

Άδικα κλαις. Τα κροκοδείλια δάκρυά σου δεν με συγκινούν. (= You're crying in vain. Your crocodile tears don't move me.)

Η αστυνομία στο συλλαλητήριο χρησιμοποίησε δακρυγόνα. (=At the rally, the police used tear gas).

If you are not sure how some of these words are pronounce, you can hear me read the declension table, derivatives and examples in the mp3:

Any questions?

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dog speech in modern greek, english and spanish

In english, dogs bark. The verb "to bark" comes from a germanic root (by the way, it's not the same root as the bark of a tree). And them dogs go "woof". And that's fine, woof resembles a sound a dog would make.

In spanish, dogs ladran. The verb ladrar comes from latin latrare, with the same meaning. The thing is, in spanish, dogs go "guau". Well, it may not be much in writing, but if you listen how the spaniards pronounce it, it's pretty close! (You can hear it in this video, in 4:52).

And then, we have modern greek. So, in modern greek, dogs γαβγίζουν. And that's because in greek, dogs go "γαβ". As a native speaker, I acknowledge that γαβ doesn't resemble a dog's bark but that's what we use, anyway. So, get used to it :)

So, we got the γαβ sound, we added the common verb ending -ίζω and we came up with verb γαβγίζω. You can hear me go γαβ in the mp3 file at the end of the post.

And here's how to form all tenses of the verb in the first person singular.

Το these, I would add two forms of conditional. Θα γάβγισα (= I must have barked) and θα γάβγιζα (= I would have been barking).

Oh, and there's the word for the bark itself, which is γάβγισμα.

In the mp3 file, you can hear me pronounce γαβ, γάβγισμα and also read the greek in the table above.

You can now bark succesfully in modern greek.

#spanish#language#greek#modern greek#alangblrofsorts#barking#ladrar#γαβγίζω#γαβ#ελληνικά#ισπανικά#αγγλικά#guau#woof#etymology#latin#latrare

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Αγαπημένος: loved one and favourite

Αγαπημένος is a passive participle of the verb αγαπώ (= I love). As you may know, participles are fully declinable in modern greek.

So, one meaning of this participle is the "loved one". It can be used for a relationship that is strong, ie relatives, friends, partners, relationship etc.

Αυτό είναι ένα πολύ ωραίο δώρο για τους αγαπημένους σας. = This is a great gift for your loved ones / Este es un gran regalo para tus seres queridos.

But this is not this participle's most common use. Its primary use is to convey the meaning of favourite in english or favorito in spanish.

Αυτό το ποίημα είναι από τα αγαπημένα ποιήματα της μητέρας μου. = This poem is one of my mother's favorites. / Este poema es uno de los poemas favoritos de mi madre.

So, in english and spanish, you favour something over other things, whereas in modern greek you love it.

#spanish#language#greek#modern greek#english#langblr#favourito#favorite#participles#meaning#alangblrofsorts

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#greek #modern_greek

Aquatic etymologies

The Modern Greek word for water is νερό (neró). However, this is not the standard word used historically in the Greek language. In Ancient and Koine Greek, the standard word for water was ύδωρ (íðor). As I also said in a post recently, there are not really dead words in the Greek language. For instance, ύδωρ might not be used in everyday speech anymore but nothing prevents you from doing it and being understood as long as you don’t care to be called an eccentric. But that’s the weakest of the arguments.

If you want to use a plural, namely “waters”, which is more common in Greek than in English, then the plural of ύδωρ suddenly becomes a standard, common word to use! The plural of ύδωρ is ύδατα (íðata) and it is way more acceptable in official contexts. For example, if you want to say “territorial waters”, you will say χωρικά ύδατα (horiká íðata). The plural of νερό is νερά (nerá) and it can be used only in more informal situations.

But there’s another way the word ύδωρ beats the seemingly prevalent word νερό. Although the singular νερό for water is by far the standard everyday choice and whereas the plural of both words is used in different scenarios, all, literally all derivative words associated with water come from ύδωρ only. This is something evident in the English language as well with words of Greek origin with the hydro- root i.e hydrogen, hydrological, hydrophobic and so on. The root hydro- or ύδρο- in Greek is a form coming from ύδωρ. There is resolutely no derivative word coming from νερό.

So one could make the assumption that νερό is a foreign loanword entering the language only recently or some modern lingual creation, while all water derivatives remain traditional. But the funny part is that it is not. Νερό is as Ancient Greek as ύδωρ. Νερό (neró) comes from the ancient νηρόν (nērón) meaning fresh, young, rejuvenating. The ancient Greeks would often use the phrase «νηρόν ύδωρ» (nērón hüdor in a more ancient pronunciation) meaning “fresh, rejuvenating water”. It could also mean “drinkable water”. Evidently, the word for water (νερό) in modern Greek is linked to the word for young (νεαρό - nearó) and both of course originate from the PIE root for “new” (νέο - néo in Greek).

While νερό means generally fresh and rejuvenating, it has been specifically linked to these desirable qualities of water since antiquity. This is why there is the God Νηρεύς (Nereus), son of Pontus (the Sea) and Gaea (the Earth), an old god of the sea with the powers of shapeshifting and prophecy. Nereus was the father of the Nereids, lesser deities of the calm sea, one of which was Thetis, Achilles’ mother.

And here’s how the everyday plain word νερό is not at all more modern and unimpressive than the posh and archaic word ύδωρ.

Nereus

202 notes

·

View notes

Note

I understand Greek is part of the Indo-European language family. Why does nai mean yes while similar sound means no almost universally in the other languages. Was ancient Greek any different? Thanks 🙏

First of all, the resemblance of the Greek yes (ναι - nai) with the Indo-European variations of no is entirely coincidental.

Both Modern Greek words for yes and no come from Ancient Greek. Interestingly, Ancient Greeks did not use direct yes and nos often. They would express affirmation or objection with full phrases.

However, ναι already appears in the Homeric epics and it is an enthusiastic affirmation. It didn't mean exactly "yes", but rather an "Indeed!" exclamation. In the process, its usage became plainer and more generic.

The Modern Greek όχι (ókhi - no) comes from the Ancient Greek οὐ(κ) [ou(k)] which is a negative meaning "not". Ancient Greek had many negative words from different roots that were used in basically the same way, i.e

1. the οὐ from which many words derived such as

ουκ - not, another form of οὐ

ουδείς - nobody

ουδέν - nothing

ούτε - neither

ουχί - of course not!

2. the μή (mē) with derivatives such as

μηδείς - nobody

μηδέν - nothing, and also the number zero

μήτε - neither

3. AND the νή (nē) which as you probably guessed is the common Indo-European root for no!

They all survive in Modern Greek in different ways. All the derivatives I listed as examples are used in everyday Modern Greek too.

As for the roots themselves:

The οὐ (ou) survived through its more enthusiastic version ουχί (oukhí) meaning "Of course not!" which gradually became όχι (ókhi), and came to mean the simple modern no.

The μή survives intact and it means "don't" in the imperative i.e "Don't speak!" is "Μή μιλάς!". It also has an equivalent use as “non” i.e non-talkative = μη ομιλητικός.

The νή is the most obscure of all, surviving intact only in a few derivative words such as the word "νηνεμία" which means ¨windlessness¨ and it was exactly like that in the Homeric Greek already.

BONUS: The Modern Greek word for "not-don’t" in the indicative is δεν (then). Did you notice the ουδέν and μηδέν I wrote above, both meaning "nothing"? Δεν is short for these words, generally believed to come specifically from ουδέν.

Why Greek showed such preference for οὐ and μή over νή, unlike the other Indo-European languages, is a mystery. However, linguists have found οὐ sounding negatives in Mycenaean Greek texts in Linear B script (meaning before the creation of the Greek alphabet and before the 13th century BCE) so this one is very old too. There have been some hypotheses as to how οὐ evolved to be a negative but nothing certain yet.

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hiking in Greek

Hiking - Πεζοπορία Path/trail - Μονοπάτι Forest - Δάσος Tree - Δέντρο Climbing - Ορειβασία Bag - Τσάντα Hat - Καπέλο or Σκουφί Walking shoes - Παπούτσια για περπάτημα Hiking boots - Μπότες πεζοπορίας Gloves - Γάντια Sunglasses - Γυαλιά ηλίου Water - Νερό Sun screen - Αντηλιακό Snacks - Σνακ Sandwich - Σάντουιτς Granola - Γκρανόλα Bike - Ποδήλατο Mountain bike - Ποδήλατο βουνού Bicyclist - Ποδηλάτης Bridge - Γέφυρα Stone - Πέτρα Boulder - Ογκόλιθος Animal - Ζώο Mountain - Βουνό Hill - Λόφος Plant - Φυτό Photography - Φωτογραφία Camera - Φωτογραφική μηχανή Compass - Πυξίδα or Μπούσουλας Dog - Σκύλος Waterfall - Καταρράκτης Lake - Λίμνη Scenery/landscape - Τοπίο

as always, feel free to correct anything

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cuñado and the way spanish and modern greek sound

Cuñado means brother-in-law in spanish. We all know how this is pronounced. Ok, we all may not, so it´s pronounce like this: kuˈɲa.ð̞o. So, this word derives from latin cognatus, which meant kin, blood relation (among other things.

So, how’s brother-in-law in modern greek? Κουνιάδος. I mean, apart from the -s ending, the pronounciation is identical. The feminine forms are identical too: cuñada - κουνιάδα. So how did this word end up in modern greek? Well, we actually got it from venitian, a old form of italian. Yeap, italian, latin, you know... We got cognado (that also derives from cognatus) and we turned the gn into a ð̞ sound, much like the hispanohablantes did. We also turned the co- sound into a cu- (κου) sound.

Isn´t that interesting? I mean, spanish and modern greek... language-wise we have nothing in common but our sound systems are very, very close.

#greek#modern greek#spanish#español#cuñado#sound system#etymology#venitian#ð̞#italian#pronounciation#greek langblr#langblr

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geography of Greece - Γεωγραφία της Ελλάδας

Mountain - Βουνό +Mount Olympos - Όλυμπος +Taygetos - Ταΰγετος +Pelion - Πήλιο +Kyllini - Κυλλήνη or Ζήρεια +Mount Parnassos - Παρνασσός

Canyon or Gorge - Φαράγγι +Samariá Gorge - Φαράγγι της Σαμαριάς

River - Ποταμός +Achelous - Αχελώος or Ασπροπόταμος or Άσπρος

Lake - Λίμνη +Lake Kremista - Λίμνη Κρεμαστών

Volcano - Ηφαίστειο Volcanic crater - Ηφαιστειακός κρατήρας

Landscape - Τοπίο

Earth - Γη Ocean - Ωκεανός Sea - Θάλασσα

Forest - Δάσος +Tree - Δέντρο +Animal - Ζώο

North - Βόρειος South - Νότος East - Ανατολή West - Δυτικά

Region or Area - Περιοχή Border - Σύνορο

Mainland - Ηπειρωτική χώρα Coast - Ακτή Plateau - Οροπέδιο Isthmus - Ισθμός Island - Νήσος Archipelago - Αρχιπέλαγος Peninsula - Χερσόνησος Beach - Παραλία Canal or Channel - Κανάλι

Altitude - Υψόμετρο Climate - Κλίμα

Earthquake - Σεισμός Flood - Πλημμύρα Drought - Ξηρασία Fire - Φωτιά Air Pollution - Μόλυνση του αέρα Water Pollution - Ρύπανση των υδάτων

ko-fi

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Painting in Greek

Painting - Ζωγραφική Painter - Ζωγράφος Watercolor - Υδατογραφία Oil painting - Ελαιογραφία or Ακουαρέλα Paint brush - Πινέλο Paper - Χαρτί Canvas - Μουσαμάς or Καμβάς Art - Τέχνη Basic colors - Βασικά χρώματα

ko-fi

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

random Greek words

θεσμός - institution δημόσιο - public ανακαίνιση - renovation αγώνας - match (sports) αγωνία - agony, anguish πυκνός - dense, thick κάπως - somewhat ύποπτος - suspicious σταθερός - steady μικτός - mixed ανυπόμονος - impatient υποχρεωτικός - compulsory φιλόδοξος - ambitious

ko-fi

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bees ! in Greek

μέλισσα | bee + μέλισσες | bees έντομο | insect + έντομα | insects κυψέλη | beehive μελισσοκόμος | beekeeper βασίλισσα | queen κεραία | antenna + κεραίες | antennae κηφήνας | drone εργάτης | worker σφήκα | wasp + σφήκες | wasps σμήνος μελισσών | bee swarm γύρη | pollen νέκταρ | nectar μέλι | honey κηρήθρα | honeycomb επικονίαση | pollination

ko-fi

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

random Greek words

θεσμός - institution δημόσιο - public ανακαίνιση - renovation αγώνας - match (sports) αγωνία - agony, anguish πυκνός - dense, thick κάπως - somewhat ύποπτος - suspicious σταθερός - steady μικτός - mixed ανυπόμονος - impatient υποχρεωτικός - compulsory φιλόδοξος - ambitious

ko-fi

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Δεν ξέρω πώς γράφεται αυτό. = I don’t know how to write/spell this.

Δεν έχω ιδέα τι σημαίνει αυτό. = I have no idea what this means.

Ούτε που ξέρω τι σημαίνει! = Ι don’t even know what it means!

Πού να ξέρω τι σημαίνει αυτό; = How am I supposed to know what that means?

I Just Don’t Know 🤷🏻 in Greek

Μαθαίνω Ελληνικά. - I am learning Greek.

Μελετώ Ελληνικά. - I am studying Greek.

Δεν είμαι καλή στα Ελληνικά. - I am not good at Greek.

Τι σημαίνει αυτό; - What does this mean ?

Δε νομίζω. - I don’t think so.

Συγγνώμη, τι εννοείτε/εννοείς; - Sorry, what do you mean ?

Δεν ξέρω τι σημαίνει αυτό. - I don’t know what this means.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Youtube stuff

I’d like to share some youtube stuff you may already know, but still...

So, as far as spanish is concerned, I find the people on español automatico most helpful, as they speak rather fast and get you accustomed to the speed most spanish native speak. They also give great tips.

Then, there´s Salo on use your spanish who does something remarkable. In each video, he introduces a story in slow spanish, then explains the difficult stuff, then retells the story in normal speed. It´s quite helpful and the way he explains things (always giving examples) is wonderful, to say the least.

And then, there´s Linguriosa, whose hillarious ways teach us etymology-related stuff. She rocks. Period. But that´s not all. It seems that she has formed a group with three other people (french, italian, portuguese) called Liga Romanica. In their channel they discuss language related stuff, each one using their own language. It´s really interesting, even if you don´t speak all four languages. One of the members, the italian, has this excellent podcast italiano. It´s great if you´re learning italian.

On other news, there´s this pretty funny spaniard who lives in Greece and is teaching spanish in greek. He´s Darío Acebales. If you´re learning both languages, he´s the thing.

So, check them all out.

#spanish#italian#greek#modern greek#salo#use your spanish#español automatico#darío acebales#liga romanica#podcast italiano#linguriosa

0 notes