Text

TWICE, a JYP Entertainment girl group

EXO, a SM Entertainment boy group

0 notes

Text

Essay 3: K-pop and how it’s problematic

K-pop is one of those contemporary representations of transnational Asians in globalized media and popular culture that is considered both problematic and some-what liberating and empowering. The K-pop phenomenon has become globalized and is reaching both members and non-members of the diaspora. This is evidenced by the “search volume for [k-pop and kpop rising] exponentially since 2009″ (Fuhr 2013:61).

K-pop is a highly orchestrated and organized industry. During the 1990s, Korean music business underwent a “substantial shift toward an era of increased global awareness among musicians and music producers and saw the emergence of artists management companies as new powerful players in the music market” (Fuhr 2013:59). Thus, establishing the fact that kpop has become a global sensation starting from the 1990s. Another one of these “booms” can be seen today with many kpop boy groups being featured as nominees of international award shows.

The training system that these idols go through is very gruesome and the entertainment companies usually try and control several aspects of their lives, whether that be their weight, their visuals, or even their love lives. To these entertainment companies, their trainees and their idols are “the most valuable goods in the transnational movement of Korean pop culture” (Fuhr 2013:67) and they are being viewed as objects for profit.

The focus on the “idol star system” (Fuhr 2013:67) is key to understand the problematic ways entertainment companies create and enforce this system. This focus is due to the small music market and “the continuous decline in physical music sales since the early 2000s” in Korea, which “led management companies to develop a long-term business model that largely concentrates on two principles: music export and the idol star system” (Fuhr 2013:67). Lee Soo-Man, founder of SM Entertainment - one of the big three in Korea, is “credited with...[inventing] a system for cloning young talents and grooming pop stars” (Fuhr 2013:68). SM Entertainment is also known to have one of the most grueling training systems, many trainees dedicate years and still don’t get the chance to debut.

Another one of the big three in Korea is JYP Entertainment. This company is known to be more humane and treat their idols with respect. Park Jin-Young (JYP) “argued that a consistent star image is key to developing stars with high added value and that the in-house production system of Korean companies may be most effective in meeting this requirement” (Fuhr 2013:69). The key word here is the use of “production” to describe the training system, this gives the impression of viewing these people as objects and/or money-making machines.

The trainee system comes to life through a “highly diversified manufacturing system with multiple division catering to different yet interlinked operating fields” (Fuhr 2013:70). These entertainment companies are highly complex and every division is part of the process for a debut or a comeback from one of their many idol groups. The companies take a strong focus on “figure and appearance” of their idols, sometimes even making it a requirement to get work done on their face before they’re able to debut. Of course, the entertainment companies indulge in favouritism and thus “neglecting others who then quickly feel alienated, lonely, and in despair” (Fuhr 2013:80). These idols also “represent behavioural codes” that are ingrained into them “right from the beginning of idol apprenticeship” (Fuhr 2013:80). These idols must represent the epitome of being a good person while also balancing the weight of fame and grueling work hours. The worth of these idols amounts to nothing more than the hard work of the entertainment companies and how they are purely a “result from the elaborate training system in which idols are drilled for many years to become all-round entertainers” (Fuhr 2013:81).

A lot of idols don’t have the chance to participate in the production of the songs that they sing, especially idols of the big three in Korea. The whole point of the idol trainee system is to differentiate idols from artists. Many western artists participate in the production of their music since it’s deeply personal to them. However, in the case of idols in Korea, the majority do not participate in the production of the music they’re going to release. Many music producers (Teddy, JYP, etc.) “make extensive us of [a] form of self-crediting to acoustically and visually brand their songs and to strengthen the label’s corporate identity” (Fuhr 2013:73). This further establishes the whole idea of idols not being able to really contribute to the music.

Entertainment companies are known to have dating bans during the first few years of an idol group’s career. This dating ban can harbour feelings of ownership from fans because they view these idols as a potential significant other. Once the dating ban is lifted, fans can feel betrayed when news break out that their favourite idols are dating another idol. Thus, the suspended belief that they could create personal relationships with their favourite idols is broken. Since “idols have become the centre of the music business, and music has become their vehicle” (Fuhr 2013:81), this further emphasizes the idea that these idols are being seen as objects and as solely a means of profit for the companies instead of seating them as human beings.

Even though, kpop is drowning in its’ problematic ways, there are certain aspects of kpop that are liberating and empowering for the consumers. Kpop is liberating because it is able to reach such a wide audience and allows members of the diaspora to feel seen since the West usually doesn’t have many Asian musical artists or idols that are huge and successful. It is also a representation of how hard work pays off and thus, it can inspire audiences and consumers to work in their own endeavors in order to gain success in their respective fields.

Personally, I am implicated in the circulation of K-pop representation because I am a fan, consumer and member of the diaspora. To see the dedication and perseverance of my favourite girl group, TWICE, pay off and have people all around the world know who they are and their achievements pushes me to work hard and make my personal dreams come true.

Kpop is extremely problematic when it comes to the treatment of their idols and their trainees. Being a fan of kpop, all that can be asked of us is to understand how problematic the industry is and fight for their favourite groups to succeed in this globalized media.

Sources

Fuhr, Michael. 2013. “Producing the Global Imaginary: A K-Pop Tropology.” Globalization and popular music in South Korea: sounding out K-pop. 59-124

0 notes

Text

Essay #2

youtube

A great video I found on Youtube talking about when gay ships become borderline fetishism. Gives great examples of shipping celebrities!

0 notes

Text

Essay #2

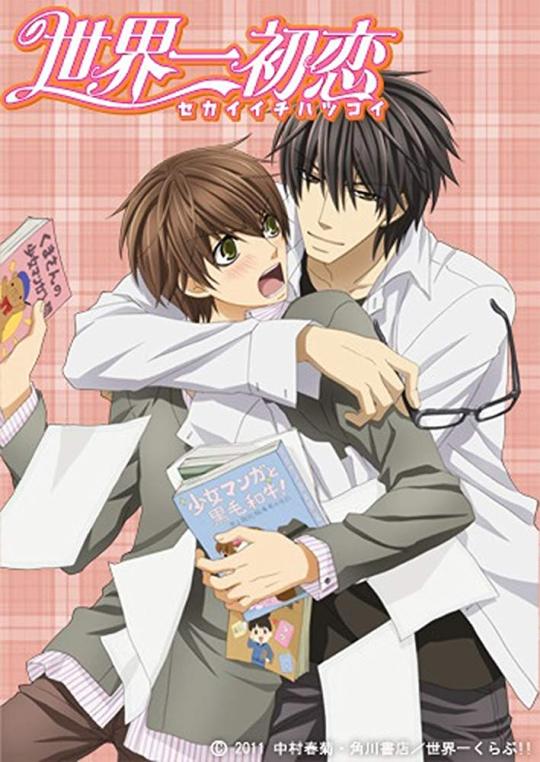

Anime adaptation of the popular boys’ love manga Sekaiichi hatsukoi

An example of sexualization of gay relationships in boys’ love manga. (and this is even one of the tamer images I found)

0 notes

Text

Essay #2: Gay Men and Fetishism

Typically, when we think about LGBTQ+ representation along with the word fetishism, we tend to think about lesbians and the fetishism from men they receive. We rarely ever think of gay men and the fetishism they experience from women. In this essay, I will be discussing the connection between the corporeal representation of boys’ love manga and the incorporeal representation of sexuality in modern Asia, the pattern of exclusion as a result of these representations and how I am implicated in this representation.

How does the corporeal representation of gay men in boys’ love manga connect with the incorporeal representation of sexuality in modern Asia? First of all, the corporeal representation in boys’ love/yaoi manga (see fig.1) creates the

Fig. 1 IMDB. Sekaiichi hatsukoi. (2011). Digital. 709px by 1000px

incorporeal representation which is the idealization of the sexualities and experiences of gay men. In the article, “Lilies of the Margin: Beautiful Boys and Queer Female Identities in Japan,” Welker talks about how magazines were created to accommodate the “growing fixation on ‘beautiful boys’” (Welker 49) by women. The articles written in the magazine would be “sympathetic in tone” (Welker 49) but were actually putting themselves in a position of viewing these boys as objects of the female gaze. This could lead to the fetishism and sexualization of gay men and their romantic relationships. This is a problem because it misrepresents the experiences of gay men in Japan by assuming that their lives are exactly like those depicted in boys’ love or yaoi manga. This can be damaging to men when they are still exploring their sexuality and understanding who they are. A cycle of fetishism is created when people aren’t able to differentiate from fictional lives of gay men in boys’ love and the real lives of gay men in everyday Japan. The idealized representation of gay men from the perspective of women occurred because the boys’ love genre was largely contributed by women authors who “interested themselves in male homosexuality” and they “did so in the context of highly romantic stories of beautiful youths” (McLelland 460). They were “unconcerned with social realism,” (McLelland 460) which establishes the idea that they did not really understand or care to understand the experiences and struggles of being a gay man in Japan. They created this representation not for gay men of Japan but for other women. So, what is the big issue with women being interested in stories about gay men, their sexual relationships and their experiences? What is the point at which it becomes fetishism? When do the agencies of gay men get taken over by the narratives of women? It is a fine line that these women walk. Are these women excited and screaming over “an absolutely adorable couple that could make anyone’s eyes turn into pink hearts” or were they just “losing their minds over the simple idea of two men being in love?” (Santen) The question that we need to ask here is whether or not under the same circumstance, would these women react by screaming and getting overly excited if it was two women or a man and a woman instead of two men. If the answer is no, then the line has been crossed.

Patterns of exclusion occur as a result of boys’ love as gay representation in modern Asia, specifically Japan and how it relates to the misrepresentation of gay men in their own representation. The agency of gay men is being disregarded in favour of what women have to say about the gay male experience in their writing or other forms of media they create. Women can “take ownership of the gay male experience by writing about it and reading each other’s writing” and in doing so, their voices are being heard over the voices of gay men. This emphasizes the patterns of exclusion within this mainstream media of boys’ love in Japan. This exclusion of gay men in their own representation further alienates them and puts pressure on them to act or dress a certain way in order to fit into the stereotypes and assumptions of how gay men are like that women created in the boys’ love genre. Women “attempted to co-opt the gay male experience” or they would “even elevate allies over actual gay men” in western representations. Even though it is the context of western representation of gay men, it is still relevant to gay men in Japan because if it happens on one side of the world, it is bound to happen on the other side of the world. This erases the struggles of being a gay man in Japan (or anywhere in the world for that matter), and paints this idealized, romanticized and sexualized experience of gay men which is inaccurate and harmful.

Personally, I am not implicated in this representation because I have never read boys’ love manga nor am I a gay man. Therefore, I can only speak from the perspective of an outsider who has experienced similar situations. As as Asian lesbian, I have had experiences where once men find out my sexuality, they start making comments that are fetish-y and uncomfortable. The fetishism of lesbians by straight men largely comes from porn because a lot of the comments that are said tend to be sexual in nature. Obviously, this experience is not exactly the same as the fetishism that gay men experience, but I can stand in solidarity with them and try to bring awareness and make people question their attitudes towards the LGBTQ+ community.

All in all, women who consume boys’ love media and other media similar to it (whether that be in Asia or outside of Asia), should ask themselves whether or not the representation they are creating is positive of harmful. They should also ask themselves whether or not their attitudes towards gay men in real life are crossing the line of fetishism and if they would act the same way in real life if they saw two women or a woman and a man together in public instead of two men. At the end of the day, we are all just people and everyone deserves to hvae accurate representation in the media. Misrepresentation for the LGBTQ+ community is a big problem and we can all take steps to create a space for better representation regardless if you are an ally or a member of the LGBTQ+.

Work Cited

IMDB. Sekaiichi hatsukoi. 2011. IMDB. Web. 27 October 2019.

McLelland, Mark. “Is There a Japanese ‘Gay Identity’?” Culture, Health & Sexuality, vol. 2, no. 4, 2000, pp. 459-472. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3986702.

Santen, Kiri Van, et al. “On The Fetishisation of Gay Men By Women In The Slash Community.” The Festishisation of Gay Men By Women In The Slash Community | The Mary sue, 17 Jan. 2015, https://www.themarysue.com/fetishizing-slash/.

Welker, James. “Lilies of the Margin: Beautiful Boys and Queer Female Identities in Japan” AsiaPacifiQueer: Rethinking Genders and Sexualities, edited by Fran Martin and Larissa Heinrich. 2006. pp. 46-66.

0 notes

Text

IMPORTANT!

click the navigation bar on the upper left corner to access the essays (each essay includes video and image representation posts). PLEASE VIEW THIS BLOG ON A DESKTOP AND NOT ON MOBILE !!!

0 notes

Text

Essay #1

youtube

Breakfast at Tiffany’s opening scene where a white actor is doing yellowface.

youtube

Great VOX video about the history of yellowface in Hollywood!

0 notes

Text

Essay #1

An example from the movie Argo (which is based on a true story) having a white woman play the role of a real life Asian woman!

0 notes

Text

Essay #1

Asians are one of the least represented minorities in Western media and when they are represented, it is usually portrayed by white actors and actresses. The history of immigration and assimilation is to blame for the contemporary representation of Asians in Hollywood and Western media today. In this essay, I will be discussing how white media has become more criticized over the years and how Asians tend to perpetuate stereotypes about themselves in order to appeal to non-Asian audiences in their representations.

Western media, or white media, has become more and more criticized over the years because people of colour are using their voices to fight for the representation of minorities that has been severely lacking for several decades in Hollywood. The Asian community criticizing Hollywood and white media is an attempt to free themselves from the harmful stereotypes put upon them and an attempt to fight for a place to create their own representation without erasing their cultures or their histories. Even though Hollywood is attempting to allow minorities the representation they deserve, it still isn’t enough and there are still a lot of problems. One of the many problems is that Hollywood and other associated medias are still being perceived as a white only space, which prioritizes the cisgender, heterosexual, white, male gaze in stories geared for the general public. It also appears to be an industry for these white men to fantasize about their importance in the stories of other people. This, to a degree, allows them to feel justified when Hollywood and white media continuously cast white actors and actresses to play Asian roles or when they completely erase Asian in (see fig. 1) in stories that have Asian people.

Fig. 1 IMDB. Argo. (2012). Digital. 1600p x 1067p

However, even after Asian people get the representation they deserve, the roles given to them by Hollywood are still filled with stereotypes that make Asians on screen appear two-dimensional with no character depth or roles that are over-sexualized. Furthermore, this representation was created by and for the consumption of white men who fantasize about being the centre of every story. This fantasy isn’t their fault, white men are used to being the focus of the media in Hollywood. The problem that Hollywood has is this problem of taking stories or histories that are about non-white people and miraculously finding a way to make it about white people while also simultaneously whitewashing the context in order to appeal to the general public and the Oscars Academy. A sad truth but we have more white Oscar winning actors and actresses doing yellowface than actual Asian actors and actresses winning Oscars.

How does the criticism of white media from the Asian community correlate with Asians creating their own representation? First of all, this criticism allowed the Asian community to create a space where they can explore what positive representation means and how that influences other Asians. Nevertheless, while exploring positive representation in media that Asians created, sometimes they end up perpetuating stereotypes they so desperately wanted to move away from. In addition, the media they create sometimes unconsciously falls prey to the white gaze. Some of the media take on a subtle stance of mockery towards their culture and traditional values in order to appeal to the general public and not just Asian audiences. This mockery is usually implored by media portrayed from the white gaze. Media is often a reflection of what is occurring in reality, however not when it is Asian representation in that media. This idea that non-Asians, particularly white Caucasians, feel discomfort when presented a piece of media that has nothing to do with them, that has no positive representation for them and was not made with the white gaze in mind, is a reason why there was a lack of representation to begin with. It also makes one question if this discomfort from media can also be translated into the real world as racism. When white people are no longer the centre of attention or focus in stories about people of colour, they become critical of minority representation. This criticism could be the product of unconscious racist attitudes that white audiences harbour. This attitude has deep roots in early 20th century America, where white Americans viewed foreigners as being able to easily overwhelm the American identity. From the article, ��The ‘Negro Problem’ and the ‘Yellow Peril’ Early Twentieth-Century America’s Views on Blacks and Asians” by Julia Lee, she discusses how racial exclusions directly correlates to white power being threatened. She also discusses how the American identity was defined by the citizenship test. (Lee) The racist notion that Asians could not and still cannot assimilate into American culture is an unconscious reason as to why Hollywood lacked positive Asian representation for multiple decades. Representation for Asians was never going to be easy, even from the start. Hollywood actually had racist rules such as not allowing two people of different ethnicities to kiss on screen, which in turn allowed for so much yellowface representation to be done.

Representation that we consume the most, allows us to change the way we view ourselves as people. The way we represent ourselves becomes distorted and influenced by both white media and the white gaze.

Works Cited

IMDB. Argo. 2012. IMDB. Web. 30 September 2019.

Lee, Julia. “I“The ‘Negro Problem’ and the ‘Yellow Peril’ Early Twentieth-Century America’s Views on Blacks and Asians.” Interracial Encounters. 2011. Sept. 2019. pp. 22-47. NYU Press.

0 notes