Hello, I'm a guy with a blog. That's really all there is to it.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Why ‘You’re Gonna Go Far, Kid’ by The Offspring Can Be Seen As Being About Lord Of The Flies (Part 1)

In this essay, I will be conducting a brief analysis of the lyrics to The Offspring’s ‘You’re Gonna Go Far, Kid’ and elaborating on why I personally firmly feel that the song can be viewed as being from the perspective of Ralph and addressing Jack and his actions throughout the novel. This is, of course, my own interpretation and highly speculative, and the only people who can either confirm or deny this lyrical analysis are members of The Offspring themselves.

***

Firstly, the title in itself, I believe can be interpreted as being directly addressed to Jack, with use of the word ‘kid’ to emphasise not only the youth of the boys on the island, but also in order to highlight Jack’s own immaturity. The title as a whole, ‘You’re Gonna Go Far, Kid’ seems to indicate a sense of frustration towards the individual and their actions, and suggests a degree of annoyance. This, I believe, is done to depict Ralph’s anger with Jack, and so features a heavy use of sarcasm to underline this, indicating that Jack’s actions and general demeanour will, in fact, get him nowhere in life.

***

“Show me how to lie,

you’re getting better all the time”

Here, the first person speaker (Ralph) appears to have maintained the sardonic tone seen in the title. Requesting that the recipient of the song (Jack) teaches him how to be deceptive, the speaker suggests that the recipient is ‘getting better all the time’, and thus becoming more and more dishonest and manipulative. This is very clearly the case in Lord Of The Flies, as Jack’s character is portrayed as slowly spiralling beyond control and descending into evil.

***

“And turning all against the one

is an art that’s hard to teach.”

The way in which the speaker here uses the word ‘art’ first of all indicates the continuation of the bitterly ironic tone presented from the beginning of the song, particularly when regarding an act as malicious as turning a group against an individual. In the case of Lord Of The Flies, this theme is a crucial one, and can be clearly seen in the case of the power struggle between Jack and Ralph, in which Jack’s malicious endeavour to usurp Ralph’s role as the leader of the group is achieved by turning the rest of the boys against Ralph. However, the way in which this attained arguably is an art, in a way, due to the intricate means Jack resorts to. One of which is hinted at in the following line of the song.

***

“Another clever word

sets off an unsuspecting herd.”

In this line, it can be suggested that the ‘clever word’ to which the speaker refers is ‘beast’. The notion of the beast is a heavily prominent theme throughout the novel, and is ultimately the way in which Jack usurps Ralph’s role. It is through the exploitation of the children on the island’s fear of this terrifying creature that Jack gains power. In the case of the speaker of the song being Ralph, he draws attention to this - however, also expresses a bitter and begrudging acknowledgement of the cleverness of this strategy.

-

Furthermore, the ‘unsuspecting herd’ that the lyrics refer to is an obvious reference to the ‘herd’ of children on the island, who are indeed ‘set off’ by Jack’s strategic mention of the beast. The use of the word ‘unsuspecting’ places emphasis on their youthful naïveté in their belief of the beast as a physical concept as opposed to an abstract one.

***

“And as you step back into line,

a mob jumps to their feet.”

Firstly, this reference to ‘stepping into line’ has very clear military connotations, which, due to the era in which the novel was written and set, is a very relevant theme. Alternatively, however, the ‘line’ to which the lyrics refer may indicate the order and control that Ralph’s authority brings, particularly from his own perspective, thus meaning that Ralph as the lyrical voice of the song would possess a certain degree of bias.

_

However, this line, in the case of the song being directed at Jack from Ralph’s perspective, indicates from the word ‘back’ that Jack has stepped out of line, namely by threatening Ralph’s leadership, which we know to be true on many occasions throughout the novel, particularly during Jack and Ralph’s many disagreements before Jack ultimately leaves Ralph’s group. However, this line suggests, despite Jack ‘stepping back into line’ and initially conforming to Ralph’s authority, that his (Jack’s) words have sparked something within the others that later triggers a complete power shift, implied by the depiction of a ‘mob’ ‘jumping to their feet’.

***

“Now dance, fucker, dance.

Man, he never had a chance.”

First and foremost, the use of the word ‘fucker’ can present an indication of true anger on Ralph’s part in contrast to the wry irony in the previous lines. This hints that the topic of the song is experiencing a shift from Jack’s minor crimes, such as usurping Ralph’s authoritative role and manipulating the rest of the boys using their fear of a beast, to something far more sinister. Perhaps the best example of this is in the deaths of Piggy and Simon. The use of the word ‘dance’ implies that this sudden shift in tone is, in fact, in relation to the death of Simon, as the conditions of his murder in the novel featured a ritualistic ‘dance’ of sorts, in which Simon, who approached the group to inform them of his revelation - that the beast was, in fact, an abstract concept, was murdered upon being mistaken for the beast.

-

Furthermore, the line ‘Man, he never had a chance’ in relation to Simon is arguably intended to depict Ralph’s insight as to the survival odds of the likes of Simon, as well as potentially Piggy and the boy with the mulberry coloured birthmark, as the three of them were characters who were set apart from their peers, be it physically (the child with the birthmark), mentally (Simon, due to his abstract and philosophical way of thinking in contrast with the other boys’ approach) or both (Piggy, both as a result of his weight and his general tendency to disagree with the majority and present alternative solutions, which are frequently dismissed.) As a result, none of these characters, in hindsight, ‘had a chance.’

***

“And no one even knew

it was really only you”

At a first glance, it may be easy to argue that this particular line, unlike those prior to it, addresses Simon instead of Jack, and his mistaken identity in the scene of his death. However, my personal interpretation of this line is that it refers to the mass hysteria brought on by a fear of the beast. While the beast is thought by the boys (bar Simon) to be a concrete and living creature, it is later revealed in the novel that the beast is, in fact, an abstract personification of the boys’ inner savagery.

In context of this song, however, it is arguable that it is Jack who exhibits the greatest decline into savagery, rivalled only by Roger, and thus, a potential argument is that Jack is the personification of savagery, and thus the personification of the abstract concept of the beast for which Simon was wrongly mistaken.

***

“And now you steal away.

Take him out today.”

Initially, it may be argued that this line refers to Jack’s leaving of Ralph’s group. However, the word ‘steal’ indicates a degree of stealth that was clearly absent from Jack’s storming away from Ralph in the novel. Therefore, my personal interpretation of this line is that this process of ‘stealing away’ refers less to Jack physically leaving and more to his psychological detaching of himself from Ralph’s group, rules and ideals. In this context, the notion of ‘stealing away’ seems far more accurate, and much more subtle, as this metaphorical edging further and further away from the society built by Ralph at the beginning of the story is initially only depicted through small remarks and disputes.

-

Furthermore, the line ‘take him out today’ can refer to Ralph. However, in the context of Ralph as the speaker, the use of this third person speech is arguably used as a tool in order to depict Ralph as attempting to view the situation from the perspective of Jack, who desires to ‘take him (Ralph) out’ initially in the sense of usurping his leadership role at the beginning of the novel. However, throughout the story, as Jack’s descent into savagery intensifies, this line adopts darker and far more violent connotations, clearly linking to the end of the novel, by which point Jack evidently intends to kill Ralph.

***

“Nice work you did.

You’re gonna go far, kid.”

The use of the past tense in this particular line suggests that, while the song in its entirety is arguably addressed to Jack from Ralph’s perspective, in hindsight of the events that occurred on the island prior to their rescue, this first line, ‘nice work you did’ refers to the complete summary of Jack’s actions on the island. Furthermore, the return of the wry, sardonic tone, as though expecting Jack to be proud of himself, indicates that Ralph, as the lyrical voice, is holding Jack in a very cynical light. However, in contrast to the clear hurt and anger present in his tone when he refers to Simon’s death, the tone of voice present here is spoken with a reflective sort of composure.

-

Furthermore, the future tense introduced in the line “You’re gonna go far, kid” presents a ‘what now?’ type of perspective. This is relevant to the novel in the sense that while the savagery exhibited by Jack on the island allowed him to achieve his ultimate goal, this sort of violence has no place in the civilised world that they have (presumably) by now returned to. Thus, Ralph, as the lyrical voice is regarding Jack with a cynical, almost mocking sort of tone, as he emphasises that Jack’s methods, while effective on the island, are not permitted in their (presumed) current environment.

However, on a deeper level, it can be argued that the scathing tone that implies that Jack will go a long way is intended for the listener to agree with it, perhaps beyond the knowledge of the lyrical speaker themselves. In this case, should Ralph be the intended speaker of the lyrics, he attempts to mock Jack, sarcastically claiming that his aggression and manipulation will take him far in the real world. However, we, as the older and more experienced listener know that there is unintentional truth in his words, which serve as an inadvertent commentary on society in the fact that manipulation and violence do, in fact, get one far in life.

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blaze's Compendium entry #2: Zhu Tun She: A pig? A snake? Both!?

This is a very mysterious creature, that supposedly has been spotted during the Song Dynasty, in China. (This being between 10th and 13th century)

Zhu Tun She (which means literally something like ''Snake Pig'' in Chinese) was described as a demon or monster snake, but it had four legs and behaved like a pig but violently, making squeaking noises. Some sources say it was covered in scaled and hair.

This specific creature caught my attention some years ago, and was one of the first Megaten Demons that i wanted to research by my own, because i found it very interesting. I ended up going to a Chinese Book Store in my city to research it, but it was relatively unknown even for natives. The internet has surprisingly few information about this demon, and since i do not speak Chinese, there's a huge language barrier. Still, i went on.

The most widely spread tale about Zhu Tun She in the west and Chinese web, is that it appeared during the Song Dynasty attacking peasants and soldiers, and (maybe) sometimes eating them. It was supposedly defeated by an officer who was also a magician, and managed to kill it.

From my initial superficial research in the topic, as well my more detailed one, it seems this creature is not a recurrent one. They are different from more recurrent characters, that have their own tales and whatnot. As far as i could pinpoint, at least, Zhu Tun She had just a small tale from a very specific time period. It's valid thought, that i affirm once again i am not a Chinese speaker, so if the creature appeared in other literary works, i was not able to read nor find it.

Zhu Tun She in Demi Kids. Sorry i stacked them...

The origins of the beast came from the Yijianzhi, a collection of folkloric and fantastic tales written during the Song Dynasty. This series of tales contained originally hundreds of chapters, which were complied by Hong Mai, a prolific writer from the time. Its believed that the first chapter was from around 1161, and the other ones from around 1198.

Hong Mai (1123 - 1202) was an author that decided to collect this old stories in a book. He gave the name Yijianzhi in honor to the author Yijian, which wrote according on tales he himself heard, according to Taoist Texts.

The Yijanzhi by itself is very interesting. It contains multitudes of texts, that travels around a lot of topics. From gods, to ghosts, to revenge stories, kings, fantasy, some bizarre stuff, and most important: Fantastical creatures that inhabit those legends.

In case you want to read the book... I have good and bad news: The good news is that it received a partial translation to English in 2018, i have read this version. It's called Records of The Listener and it's a simple and very rewarding read. There's also a 2007 version of partial translation. Both are properly archived and you can read it online.

The bad news is that, they are just a partial translation, many tales are missing and the Zhu Tun She one is among those missing. We do, however have a summarized version, this version was extracted from me from Chinese sources, but you can also find it on the western web. I used software to translate it, so please forgive me if i get something wrong. (See below)

But before, let's discuss it's origins a bit:

While the source mostly associated with the story, was the elusive Shigeru Mizuki book ''Dictionary of Chinese Demons'', and probably the same Kaneko took it from. There's hardly English sources about this demon, which made it very hard to research about it not being a native Chinese speaker, or at least knowing a bit of the language.

Me and some friends even pondered about it being made up by Mizuki, since it has happened before with other creatures. But with the help of the Chinese Web, i could pin down exactly where this tale was originally from:

-This was present in the book Siqu Quanshu. It's a compendium from the Qing Dynasty that contained some chapters of the Yijian Zhi including this one, you can read in it's entirety online here. (If you can read Chinese. If you can't, i will provide a translation below do not fear.)

The indexation in this book is as follows:

Siqu Quanshu -> Yijian Zhi -> 戊卷03 ( volume 3) - It's unclear how was it's original index in its original source.

(Thanks u/storiesti for helping me finding it)

The compendium in question was commissioned by the emperor Qianlong, and it's how this tales survived. That's important, because many Yijian Zhi chapters simply did not survived to the modern age, and the way some of them did was being republished in works such as that. So, at the very least it was not made up by Mizuki or anyone in the internet.

So... What was this story about then? What was our little piggy's tale?

Here's a brief version of it, translated via software, sorry it was the best i could do:

In the stationed army at Jiankang, there was a officer named Cheng Jun who was very experienced in the "forbidden spells" technique, especially in subduing demon snakes. This incident seems to have happened in the 23rd year of the Shaoxing period. (1130 AD) One evening, when the army was training outside the south gate, a snake suddenly appeared in a bamboo woods. The snake was as thick as a pestle, about three feet long, covered in fur, with four legs, just like a demon. When it appeared, it would make a sound like a pig and chase after people while making this noise, running as if it were going to devour them. People could only panic and flee with no way to deal with it. At this moment, someone nearby found a horse stable and quickly used it to trap the snake, then reported the matter to the commander. The commander immediately sent someone to investigate and also commanded Cheng Jun, who was famous for subduing spirit snakes, to take care of the snake. After a while, Cheng Jun arrived; as soon as he saw it, he recognized the shape of the demon snake under the horse stable. He said, "This is called 'Zhu Tun She', a type of demon snake that kills people once they get entangled by it." After that, Cheng Jun blew air from above the horse stable and began to use his spells. Soon, Cheng Jun commanded someone to open the horse stable, and they saw the demon snake curled up and motionless. Cheng Jun then closed the horse stable again, deeply inhaled as if he was absorbing moonlight, and then blew air from above the stable three more times. Afterwards, Cheng Jun commanded someone to open the horse stable again, and they saw that the demon snake had turned into a puddle of blood.

A.. lot happened here as you can see.

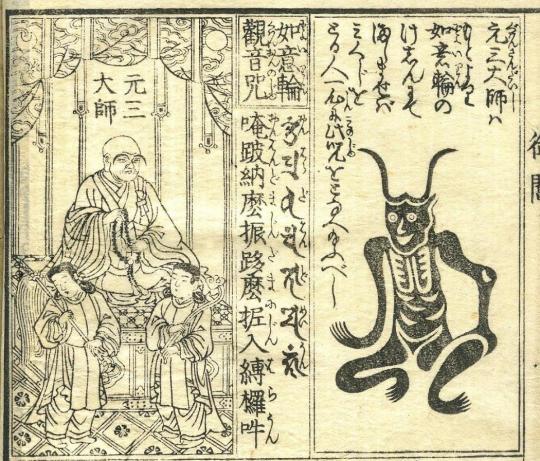

Shigeru Mizuki's depiction of the Zhu Tun She.

It's unclear how common this demon was supposed to be in that tale, since Cheng was able to identify it pretty easily, and was known to defeat monsters like that all the time.

But that is how far it goes, the creature was (to my knowledge) never mentioned again, and made brief appearances in popular media. I don't know how it ended up in Mizuki's table, but he helped to popularize it since most of sources end up in his book. This is of course because it's way more accessible to read a book from the 1990s than an old scroll from 1130s.

Zhu Tun She differs from other critters i'v researched about, because there's few to no nuance in its existence. There's no moral to the tale, there's nothing to explain it as well, it seems like a cryptid from the old world, or just an elaborated fictional tale to amuse the emperor.

My personal theory is that: If it was not made up to amuse the Emperor, it was probably a very weird capybara or something like that. Who knows?

Still it's a very fascinating demon, a creature that would be terrifying to find alone in a bamboo forest for sure. But the best part of this study was to find more about the work where it came from, the Yijian Zhi. This books are simply amazing.

It's a collection of tales from old China, some supernatural, others just common tales. Still, they are very brief and entertaining also shedding some light into old China, full of myths and stories. As i said, there's a partial translation to English available to buy, or read online! Go check it out.

As for our pig friend, i could not find out if it had other apparitions in Chinese folklore, as mentioned before. It seems Zhu Tun She was an very isolated incident, and has only known by us because someone republished the tale many years later.

You see, snakes are beings very present in Human collective consciousness. Snakes were natural predators to early humans, many of us are born with innate fear of snakes. Snake monsters, demons and gods are part of lots of cultures around the world. The Quetzalcoatl in Central America, the Hydra in Greek Mythology, Orochi in Japanese mythology. In Northeastern Brazil there's a tale of a Feathered monster Snake called ''The Lapa's Feathered Snake''. This is just some of them, while many other exist.

As our ancestral predator and a very dangerous creature, snakes ended up taking a lot of space in our minds.

It's possible that other creatures similar to Zhu Tun She have been written, but could be lost to time. Who knows? There's indeed many other snake demons around the world, so our pig friend here is not alone!

I'd like to thank sorenblr for helping me getting attention to this research, and also Atmaflare for literally accompanying me during this research. @sorenblr and @atmaflare thank you!

Hope you all enjoyed!

Sources: -Siqu Quanshu: Some Yijian Zhi tales (Original Chinese book where the tale is currently available, brought from the Yijian Zhi books)

-The Dictionary of Chinese Demons (Shigeru Mizuki, could not find it for buying but its the source parroted throughout the web.)

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Horned hermits and immoral immortals: an inquiry into Zanmu's background

As you might remember from my previous post covering Zanmu, I was initially unable to tell how her historical background led to ZUN choosing to make her an oni. The historical, or at least legendary, Zanmu seemed to be, for all intent and purposes, a human. That has since changed, and the matter now seems considerably more clear to me. Read on to learn more about the real monk Zanmu is based on, and to find out what she has in common with the most famous Zen master in history, Taoist immortals, and Tsuno Daishi. Even if you are not particularly interested in Zanmu, this article might still worth be checking out, seeing as the discussed primary sources are also relevant to a number of other Touhou characters, including Byakuren, Yoshika and Kasen.

As in the case of the previous Touhou article, special thanks go to @just9art, who helped me with tracking down sources advised me while I was working on this.

The historical Zanmu

Statue of Zanmu from the Sazaedo pagoda (Fukushima Travel; reproduced for educational purposes only) As already pointed out by 9 here even before my previous post about Unfinished Dream of All Living Ghost, Zanmu is based on a real monk also named Zanmu. His full name was Nichihaku Zanmu (日白残夢), and he also went by Akikaze Dōjin, but even Japanese wikipedia simply refers to him as Zanmu. ZUN basically just swapped one kanji in the name, with 日白残夢 becoming 日白残無. The character 無, which replaces original 夢 (“dream”), means “nothingness” - more on that later.The search for sources pertaining to the historical Zanmu has tragically not been very successful. In contrast with some of the stars of the previous installments, like Prince Shotoku or Matarajin, he clearly isn’t the central topic of any monographs or even just journal articles. Ultimately the main sources to fall back on are chiefly offhand mentions, blog articles and some tweets of variable trustworthiness. The only academic publication in English I was able to locate which mentions Zanmu at all is the Japanese Biographical Index from 2004, published by De Gruyter. The price of this book is frankly outrageous for what it is, so here’s the sole mention of him screencapped for your convenience:

The book referenced here is the five volume biographical dictionary Dai Nihon Jinmei Jisho from 1937. I am unable to access it, but I was nonetheless able to cobble together some information about Zanmu from other sources. Not much can be said about Zanmu’s personal life. He was a Buddhist monk (though note a legend apparently refers to him as “neither a monk nor a layperson”, a formula typically designating legendary ascetics and the like) and a notable eccentric. Both of these elements are present in the bio of his Touhou counterpart.

The Sazaedo pagoda (Fukushima Travel; reproduced for educational purposes only)

Zanmu’s tangible accomplishments seem to be tied to the temple Shoso-ji, which he apparently founded. He is enshrined in the Sazaedo pagoda near it, though this building postdates him by over 200 years. It’s located in Aizuwakamatsu in Fukushima. You can see some additional photos of his statue displayed there in this tweet. It’s a pretty famous location due to its unique double helix structure, and it has a pretty extensive article on the Japanese wikipedia. It’s also covered on multiple tourist-oriented sites in English, where more photos are available (for example here or here). There’s even a model kit representing it out there. Sazeado’s fame does not really seem to have anything to do with Zanmu, though. While many Buddhist figures ZUN used as the basis for Touhou characters in the past belonged to the “esoteric” schools (Tendai and Shingon), Zanmu was a practitioner of the much better known Zen, specifically of the Rinzai school.

The kanji mu (無 ) caligraphed by Shikō Munakata (Saint Louis Art Museum; reproduced for educational purposes only) Since the concept of “nothingness” or “emptiness” represented by the kanji 無 (mu) plays a vital role in Zen (see here or here for a more detailed treatment of this topic; it’s covered on virtually every Zen-related website possible though), and there’s even a so-called mu kōan, it strikes me as possible this is the reason behind the slightly different writing of the names of ZUN’s Zanmu, as well as the source of her ability. Granted, the dialogue in the games makes it sound like Zanmu (and by extension Hisami) just talks about nothingness as a memento mori of sorts, which is not quite what it entails in Zen. Of course, ZUN does not adapt Buddhist doctrine 1:1 (lest we forget Kasen seemingly being unaware of the basics of Mahayana in WaHH) so this point might be irrelevant.

The legendary Zanmu

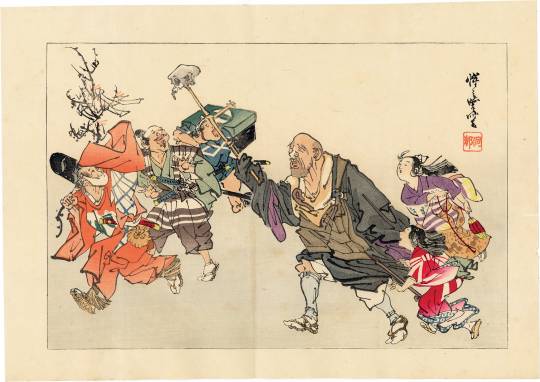

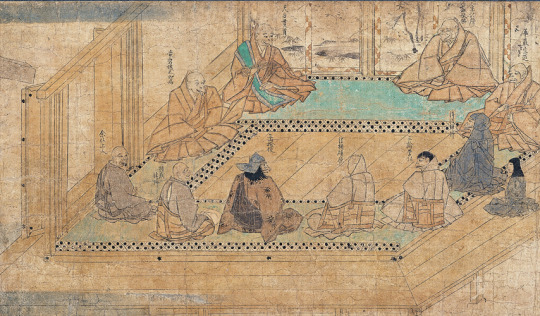

The eccentric monk Ikkyū (center), as imagined by Kawanabe Kyōsai (Egenolf Gallery; reproduced for educational purposes only)

A number of legends developed around the historical Zanmu. If this blog post is to be trusted, there is a tradition according to which he was a student of arguably the most famous member of the Rinzai school, and probably one of the most famous Buddhist monks in the history of Japan in general, Ikkyū. He is remembered as the archetypal eccentric monk, and spent much of his life traveling as a vagabond due to his disagreements with Buddhist establishment and unusual personal views on matters such as celibacy. As I already said in my previous article pertaining to Zanmu, long time readers of my blog might know Ikkyū from the tale of Jigoku Dayū and art inspired by it, though since this motif only arose in the Edo period it naturally does not represent an actual episode from his very much real career.

A page from Ikkyū Gaikotsu (wikimedia commons)

In art a distinct tradition of depicting Ikkyū with skeletons developed, as seen both in the case of works showing him with his legendary student Jigoku Dayū and in the so-called Ikkyū Gaikotsu. Skeletons also played a role in Zen-inspired art in general (for more information see here). Whether this inspired ZUN to decorate Zanmu’s rock with bones is hard to determine, but it does not seem implausible. It would hardly be the deepest art history cut in the series, less arcane of a reference than the very existence of Mai and Satono or Kutaka’s pose. Obviously, it does not seem very plausible that Ikkyū ever actually met the historical Zanmu. Ikkyū passed away in 1481, and Zanmu in 1576, with his birth date currently unknown. Even if we assume he was a particularly long-lived individual and by some miracle was born while Ikkyu was still alive, it is somewhat doubtful that an elderly sick monk would be preaching Zen doctrine to an infant. However, apparently legends do provide a convenient explanation for this tradition. Purportedly Zanmu lived for an unusually long time. The figure of 139 years pops up online quite frequently, and does seem to depend on a genuine tradition, but even more fabulous claims are out there.

Kaison Hitachibō, as imagined by an unknown artist (wikimedia commons)

According to another legend, Zanmu was even older, and in fact remembered the Genpei war, which took place in the Heian period - nearly 400 years before his time. Supposedly he told many vivid tales about its famous participants, Yoshitsune and Benkei. A tradition according to which he was himself originally a legendary retainer of Yoshitsune, the warrior monk Kaison Hitachibō (常陸坊海尊) developed at some point. This has already been pointed out by others before me in relation to the Touhou version of Zanmu. From what I’ve seen, some Japanese fans in fact seem excited primarily about the prospect of Zanmu offering an opportunity to connect Touhou and works focused on the Genpei war. The tradition making Zanmu a centuries-old survivor from the Heian period must be relatively old, as his supposed immortality is already mentioned in Honchō Jinja Kō (本朝神社考; “Study of shrines”) by Razan Hayashi, who was active in the first half of the seventeenth century, mere decades after Zanmu’s death. While I found no explicit confirmation, it seems sensible to assume this legend was already in circulation while Zanmu was still alive, or at least that it developed very shortly after he passed away. Perhaps he really was invested in accounts of that period to the point he sounded as if he actually lived through it.

The choice of Kaison as Zanmu’s original name in the legend does not seem random, as there was a preexisting tradition according to which this legendary Heian figure was cursed with eternal life for betraying Yoshitsune by fleeing from the battlefield instead of remaining with his lord to die. You can read more about this here. Apparently there is a version where he instead becomes immortal to make it possible to pass down the story of the Genpei war to future generations (this is the only source I have to offer though), and there's even a well-received stage play based on it, Hitachibō Kaison (translated as "Kaison, priest of Hitachi") by Matsuyo Akimoto. Another thing worth pointing out is that Kaison was seemingly a Tendai monk from Mount Hiei, which means that even though Okina isn’t in a new game, you can still claim she’s metaphorically casting her shadow over it in some way if you squint (and that’s without going into the fact sarugami are associated with Mount Hiei). I've seen two separate sources which mention that according to a legend he trained Benkei there, and that the two did not get along because Kaison was a corrupt monk (lustful, keen on substance abuse, greedy, the usual routine). You can access them here and here,but bear in mind they're old. Zanmu’s Genpei war connection does not really seem to matter in Touhou, though, as ZUN pretty explicitly situated his version in the Sengoku period, with no mention of earlier events. Granted, if you like it, this should not prevent you from embracing the view that Zanmu is an alter ego of Kaison as your headcanon - as I said people are already doing that. It seems equally fair game as “Okina is Hata no Kawakatsu”, easily one of the most popular “historical” headcanons in the history of the franchise. According to this twitter thread, the legends about Zanmu’s longevity (or immortality) have a pretty long lifespan themseles, as they were referenced by relatively high profile modern writers, like Orikuchi Shinbou and Tatsuhiko Shibusawa.

Buddhist immortals

A word carving of a sennin, "immortal" or "hermit" (wikimedia commons)

Legends about long-lived (or outright immortal) monks, such as Zanmu or Kaison, are hardly uncommon. A work which seems to be the key to understanding their early development, and by extension possibly also the portrayal of Zanmu in Touhou, might be Honchō Shinsenden, “Records of Japanese Immortals”. This title refers to a collection of setsuwa, short stories typically meant to convey religious knowledge or morals. Its title pretty much tells you what to expect. Honchō Shinsenden is an interesting work in that while it in theory deals with Buddhism, and largely describes the individual immortals as, well, Buddhists, it ultimately reflects a Taoist tradition. There is a strong case to be made that it was an inspiration for another Touhou installment, specifically Ten Desires, already, seeing as it mentions prince Shotoku and Miyako no Yoshika and its Taoist-adjacent context has a long paper trail in scholarship, but I will not go too deep into that topic here - expect it to be covered in a separate article later on. Stories of immortals are pretty schematic, and their protagonists can be categorized as belonging to a number of archetypes. I think it’s safe to say this has a lot to do with the self-referential character of this sort of literature - compilers of new works were obviously familiar with their forerunners, and imitated them for the sake of authenticity. In China, literary accounts of the lives of immortals circulated as early as in the first century BCE, with the concept of immortals (xian, 仙, read as sen in Japanese; this term and its derivatives have various other translations too, with Touhou media generally favoring “hermit”) itself already appearing slightly earlier. It seems Shenxian Zhuan (Biographies of Spirit Immortals) by a certain Ge Xuan, certified immortals enthusiast and cinnabar-based immortality elixir connoisseur (discussing and developing immortality elixirs was a popular pastime for literati in ancient and medieval China), can in particular be considered the inspiration for the later Japanese compilation. While the concept of immortals was largely developed by Taoists, tales focused on them were already not strictly the domain of Taoism by the time they reached Japan. They were embraced in Chinese culture in general, both in strictly religious context and more broadly in art. In Japan, they came to be incorporated into Buddhist worldview, and in fact Honchō Shinsenden states that their protagonists can be understood as “living Buddhas” (ikibotoke), a designation used to refer to particularly saintly Buddhists. Their devotion to both Buddhas and other related figures, and to local kami, is stressed multiple times too.

Presumably this was the result of the influence of the Japanese Buddhist concept of hijiri (聖), a type of particularly rigorous solitary ascetic in popular imagination regarded as almost divine. Needless to say, most of you are actually familiar with the hijiri even if you never read about them, as this is the source of Byakuren’s surname and a clear influence on her character too. In Honchō Shinsenden, it is outright said that the sign 仙, normally read as sen, should be read as hijiri in this case.

A portrait of Huisi (wikimedia commons)

The notion of extending one’s lifespan was not incompatible with Buddhism, as evidenced by tales of adepts who lived for a supernaturally long period of time to show their compassion to more beings or to get closer to the coming of Maitreya. Even the founder of the Tiantai school of Buddhism (the forerunner of Japanese Tendai), Huisi, was said to meditate in hopes of extending his life to witness Maitreya. At the same time, Chinese compilations of stories about immortals do not list Buddhists among them, in contrast with Japanese ones. This might be due to the rivalry between these religions which was at times rather pronounced in Tang China, culminating in events such as emperor Wuzong's persecution of Buddhism. Let’s return to Honchō Shinsenden, though. Its original author was most likely Ōe no Masafusa, active in the second half of the eleventh century. No full copy survives, but the original contents can nonetheless be restored based on various fragmentary manuscripts. Some of the sections are preserved as quotations in other texts or in larger compilations of stories, too. I have seen claims online that the historical Zanmu is covered in some editions of the Honchō Shinsenden or works dependent on it. So far I was only able to determine with certainty that Zanmu is covered alongside the immortals from Honchō Shinsenden in at least one modern monograph (Nishi-Nihon-hen by Kōsai Chigiri; if anyone of you have access to it I’d be interested to learn what exactly it says about Zanmu) and a number of posts and articles online. However, he lived around 400 years after this work was completed, so he quite obviously does not appear in its original version, contrary to what the Touhou wiki says right now. Masafusa does not necessarily portray the immortals as pinnacles of morality, and indeed moral virtues do not seem to be a prerequisite for attaining this status in his work. It is therefore possible that despite being setsuwa, his tales of immortals were an entirely literary endeavor and were not meant to evoke piety, let alone promote the worship of described figures.

A recurring pattern which unifies all of these tales is describing immortals as eccentric. As I already noted, this is a distinct characteristic of the historical Zanmu too, and it comes up in the bio of his Touhou counterpart as well. She has “reached the absolute pinnacle of eccentricity”. It seems safe to say ZUN is aware of that pattern, then, and consciously chose to highlight this. He also stresses that Zanmu has lived through an era of marital strife, specifically through the Sengoku period. The inclusion of such episodes is another innovation typical for Japanese immortal tales, and does appear to be a feature of the tradition pertaining to Zanmu’s counterpart too, as discussed above. Horned hermits?

A modern devotional statuette of Laozi with horns, found on ebay of all places; reproduced here for educational purposes only.

There is a further possible feature of Zanmu that might be tied to Honchō Shinsenden. While there are numerous physical traits attributed to immortals in Chinese sources, Masafusa decided to only ever highlight two. One of them are unusual bones, the other - horns on the forehead. Tragically one of my favorites, square pupils (mentioned in Liexian Zhuan), is missing. Masafusa relays that an anonymous hijiri, the “Rod-Striking Immortal”, grew stumpy horns as a sign of attaining his supernatural status.This might be a stretch, but perhaps Zanmu, due to being the Touhou version of a legendary immortal, also already had horns before becoming an oni. You have to admit it would be funny.

The two horns - or rather small bumps, based on available descriptions - characteristic for some immortals were known as rijiao (日角; “sun-horn”) and yuenxuan (月懸; “moon crescent”). Such unusual physical features were already attributed to various legendary and historical rulers and sages in China in the first century CE, so this is not really a Taoist invention, but rather an adoption of beliefs widespread in China in the formative years of this religion. They also intersected with the early Buddhist tradition about the so-called “32 marks of the Buddha”, documented for example in Mahāvastu and later in Chinese Mahayana tradition which Taoist authors were familiar with. Yu the Great, the flood hero, was among the legendary figures said to possess horns in Chinese tradition. It is even sometimes believed Laozi had them when he was born, which according to Livia Kohn was meant to symbolically elevate him to the rank of such mythical figures as Fuxi.

While this is ultimately a post focused on Zanmu, I think it’s worth pointing out this belief in horned ascetics has very funny implications for Kasen. Being a “horned hermit” is not really an issue, it would appear. If anything, it adds a sense of authenticity. Clearly Kasen needs to study the classics more.

Immortals (and mortals) in hell

One last connection between Zanmu and legends about immortals is her role as an official in hell. However, this is much less directl. Early Chinese sources mention “Agents Beneath the Earth” (dixia zhu zhe 地下主者), a rank available to low class immortals choosing to serve in the land of the dead. They could be contrasted with the immortals inhabiting heaven, regarded as higher ranked than them. However, note that there are also many narratives focused on mortals becoming officials in hell - in Japan arguably the most famous case is the tale of Ono no Takamura, a historical poet from the early Heian period. In Chinese culture there are multiple examples but I think none come close to the popularity of judge Bao. It does not seem any immortals playing a similar role retain equal prominence in culture. Ultimately this paragraph is only a curiosity, and a much closer parallel to Zanmu's role in hell exists - and it’s connected to materials ZUN already referenced to booth.

Corrupt monks, oni and tengu

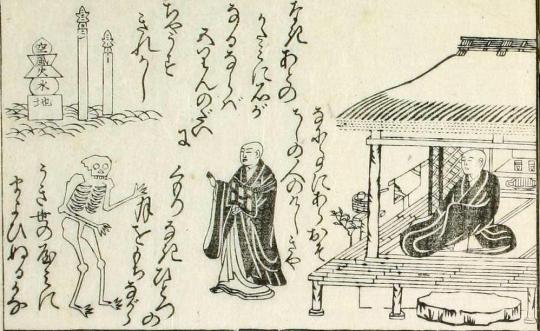

Ryōgen, the most famous monk turned demon, and his alter ego Tsuno Daishi (wikimedia commons)

In addition to characterizing Zanmu as eccentric, ZUN also wrote in her bio that she is a corrupt monk. As we learn, she developed a belief that the best way to reconcile the Sengoku period ethos which demanded boasting about the number of enemies killed with Buddhist precepts was to focus on spirits rather than the living, since she will basically deliver salvation to them. She ultimately “absorbed some beast-youkai spirits, thus discarding her life as a human”. This to my best knowledge does not really match any genuine tradition about the historical Zanmu, related figures or anyone else. As far as I can tell, it’s hard to find a direct parallel either in irl material or elsewhere in Touhou... at least if we stick to the details. More vaguely similar examples are not only attested, discussing them was for a time arguably the backbone of Buddhist discourse in Japan, and neatly explains why Zanmu became an oni. The idea that monks who broke Buddhist precepts in some way turned into monsters is not ZUN’s invention. It first appears in sources from the Heian period, and gained greater relevance in the Kamakura period. Particularly commonly it was asserted that members of Buddhist clergy who fail to attain nirvana turn into tengu. However, oni were an option too. Bernard Faure points out that Ryōgen, the archetypal example of a fallen monk (see here for a detailed discussion of this topic, and of his return to grace as a demon keeping other demons at bay), could be described as reborn as an oni, for example. The Shingon monk Shinzei is variously described as turning into an oni, a tengu or an onryō (vengeful spirit). Oni are also referenced in a similar context in Heike Monogatari alongside tenma, a term referring to demons obstructing enlightenment in general.

Corrupt monks turned into tengu in the Tengu Zoshi Emaki (wikimedia commons)

Typically it was believed that monks who turned into demons went to a realm variously known as makai, tengudō or madō. As you may know, normally there are three realms one should avoid reincarnating in - beasts, hungry ghosts and hell - but this was basically a bonus fourth one. Granted, this view was not recognized universally, and the alternative interpretation was that it was just a specific hell with a distinct name. At the absolute peak of this concept’s relevance, the foremost Buddhist thinkers of these times, including Nichiren, were accusing each other of being demons. Additionally, some of the past emperors, especially Sutoku and Goshirakawa, could be presented as tengu, for example in Hōgen monogatari. There was also an interest in finding gods who could keep the forces of disorder at bay. You can see echoes of these beliefs in rituals pertaining to Matarajin, which ZUN rather explicitly referenced in Aya's route in Hidden Star in Four Seasons. Typically the reason behind transformation into an oni, tengu or another vaguely similar being were earthly attachments. Alternatively, it could be pursuing gejutsu, “outside arts”, essentially teachings which fell outside of what was permitted by Buddhism. Note this does not necessarily mean anything originating in religions other than Buddhism, though, the term is more nuanced. So, for instance worship of kami or following Confucian values are perfectly fair game. A synonymous term was gedō, “heretical” way (on the use of the term “heresy” in the context of study of Buddhism see here). We can make a case for Zanmu’s bio alluding to that - she wanted to adhere to the social norms of the Sengoku period by symbolically taking in a headcount by absorbing spirits, I suppose. That’s not really a thing in any Buddhist literature, though, and I assume ZUN came up with this himself. Conclusion While this article is slightly less rigorous than my recent research ventures pertaining to Matarajin, let alone the Mesopotamian wiki operations, I hope it nonetheless sheds some additional light on Zanmu. I will admit I already liked her even before I started digging into the possible inspiration behind her, and finding out more only strengthened my enthusiasm. While there are clear parallels between Zanmu, her namesake and a variety of other characters from Japanese and Chinese literature and religions, as usual for a character made by ZUN her strength lies both in creative repurposing of these elements and in adding something new.

Postscriptum: Zanmu and Tang Sanzang?

Xuanzang, as depicted by an unknown Qing artist (wikimedia commons) While much about Zanmu’s character - her backstory as an eccentric fallen monk who became a demon, her apparent zen theme, and so on - all form a coherent whole, there is a tiny detail which does not really match anything else discussed in this article. It does not come from her dialogue or bio, but rather from Enoko’s. As we learn, she became immortal herself after eating a piece of Zanmu’s body back when the latter was still a human. Or rather, the combination of that and subsequently consuming a magical gemstone as recommended by Zanmu did it - I’m pretty sure I misread this before. As 9 pointed out to me, probably the implications are just that Enoko’s backstory is a partial reference to Perfect Memento in Strict Sense, which does state that consuming the flesh of a monk would be a particularly suitable way for an ordinary animal to turn into a youkai. Still, comparisons between this tidbit and Journey to the West have been made by others before already, so I figured it would be suitable to address them here even if they lie beyond my own argument about the inspiration behind Zanmu. In this novel, many demons want to devour its protagonist Tang Sanzang because his flesh is said to make anyone who consumes immortal. This is because he is a reincarnation of Master Golden Cicada (Jinchan zi, 金蟬子), a disciple of the Buddha invented for the sake of the story. Interestingly, Sanzang is portrayed as an adherent of Chan Buddhism, the school from which Japanese Zen is derived (note that his historical forerunner Xuanzang belonged to the Yogācāra tradition instead). Despite the vague similarities, I ultimately do not think there are particularly close parallels between Zanmu and Sanzang. For starters, Zanmu is meant to be a corrupt monk, while Sanzang is the opposite of that. Their respective characters couldn’t differ more either. Throughout the entire novel, Sanzang is a pretty poor planner, shows doubt in his own abilities, and regularly misjudges the situation. Needless to say this does not exactly offer a good parallel to Zanmu. Sure, she creates a bootleg Wukong, but Sanzang did not create Wukong, the famous primate was just assigned to him as a bodyguard. Therefore, until evidence on the contrary appears (for example in an interview) I would personally remain cautiously pessimistic regarding a possible connection here. Recommended reading

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Noga Ganany, Baogong as King Yama in the Literature and Religious Worship of Late-Imperial China

Zornica Kirkova, Roaming into the Beyond: Representations of Xian Immortality in Early Medieval Chinese Verse

Christoph Kleine & Livia Kohn, Daoist Immortality and Buddhist Holiness: A Study and Translation of the Honchō shinsen-den

Livia Kohn, The Looks of Laozi

James Robson, The Institution of Daoism in the Central Region (Xiangzhong) of Hunan

Haruko Wakabayashi, From Conqueror of Evil to Devil King: Ryogen and Notions of Ma in Medieval Japanese Buddhism

Idem, The Seven Tengu Scrolls. Evil and the Rhetoric of Legitimacy in Medieval Japanese Buddhism

268 notes

·

View notes

Note

You wouldn't happen to know anything about Aramisaki, do you? I've always wanted to know why is she made of lava... And while I'm on the subject...Would you happen to know anything about Kinmamon at all? XD

Not very much. Both are so obscure probably your only shot is in Japanese-language materials.

However, a long time ago I got a friend to translate a little bit of info about Kinmamon from a Japanese book, and it’s been on Giant Bomb. Here it is:

Also known as “the God from Beyond the Sea, Marebito”, Kinmamon is an enigmatic and mysterious deity of Ryukyu Shinto, a branch of Shinto obviously practiced in the Ryukyu islands. His/her connections with sea travel and the implication that he/she brought “life” to the Ryukyu islands are thought to imply it was an introduced figure and was quite possibly Amaterasu who was introduced and then changed through lack of continual contact at the time. The kanji used for Kinmamon’s name, “ 君真物 ” literally meaning “the true one”, are also thought to have been used as an honorific title for miko (shrine maidens); consequently, there is also a belief that perhaps Kinmamon is simply the evolution of the deification of miko. In addition, the kanji “ 君” is often used to write “ 神女”, megami or “goddess”, in the local Ryukyu dialect which causes even further gender confusion!Bibliography: 『琉球神道記』 袋中著 宜野座嗣剛 訳 東洋図書出版 “Records of Ryukyu Shinto” by Hiroshi Azuma. Orient Books Publications/Shorin Ronshu, 2001. ISBN-10: 4947667737

I’m pretty sure we looked into this around the time of Strange Journey’s release to try and find an explanation for the Amaterasu quest where she takes the guise of Kinmamon. This seems to explain that!

For Aramisaki, her name in kanji is 荒御前. Among her enshrinements is one at Shirayama-Hime Shrine in Ishikawa, where Shirayama-hime is another name for Kikuri-hime. But we shouldn’t ignore the important clues already in Aramisaki’s demon profile, which I think spells out basically everything that needs it:

“A violent goddess known as the Ara Mitama of the Sumiyoshi gods.When Empress Jingu went to Shinra, Aramisaki was sent by Amaterasu to protect the ship she was on. She is also a jealous god, and is known as a goddess of separation as Aramisakihime.“

First, the Sumiyoshi are sea and sailing gods. Next, the Empress Jingu goes to “Shinra”–aka “新羅“ or Silla, the ancient Korean kingdom. The legend of Empress Jingu’s invasion of Silla is recounted in both the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, where she is said to have overwhelmed Silla’s armies by “supernatural control of the tide.” Since I have the Kojiki handy, here’s a passage of interest after her conquest:

Then [Empress Jingu] stood her staff at the gate of the king of Silla and worshipped the “rough spirit” (ara-mitama) of the great deities of Sumiyoshi, whom she made tutelary deities of the land. Then she crossed back over [the sea]. Kojiki, 94:7

While it doesn’t mention Aramisaki’s name, if you go by the SMT profile, the “ara-mitama” is a more or less direct reference to the god. So if Aramisaki is the ara-mitama of the Sumiyoshi gods, that’s at least a partial explanation for her design, as, according to Philippi’s footnotes in the Kojiki here, the ara-mitama we are more familiar with is the “active, dynamic aspect of a deity”–or violent. Imagine Empress Jingu having summoned Kaneko’s fiery Aramisaki on her voyage.

But what’s strange about Aramisaki, and what this doesn’t explain, is how she seems to have become a separate deity. Same for her purported “jealousy.” I can’t think of another instance of a mitama spirit being considered separate from its divine possessor. The gods’ mitama can certainly be enshrined separately, as I was excited to find in Yasaka Shrine in Kyoto a shrine for Susanoo’s ara-mitama. If I had to make an educated guess though, I’d wager that the separate Aramisaki tradition is newer than the Kojiki or Nihon Shoki sources, with perhaps more relevant information hiding behind that Shirayama-Hime Shrine link.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Famed King Gesar

Name: King Gesar Race: Famed Description: The future emperor of Ling, King Gesar is a gifted child whose future will be full of adventure and conquest. Although the Epic of King Gesar was written in a period where Buddhism wasn’t so permeated in Tibetan society its story is full of Buddhist references.

Sprite taken from megatenktool

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dragon Kohryu

Name: Kohryu Race: Dragon Description: One of the holy dragons of Chinese lore, the Golden Dragon appears in times of great fortune or joy. His dominion over the earth extends to the four gods Long, Gui Xian, Feng Huang, and Baihu.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint Sebastian

Name: Sebastian Race: Saint Description: A Roman martyr of Catholicism who was killed by arrows while being tied to a tree. His patronage extends to archers and plague-stricken people.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Therian Lemurian

Name: Lemurain Race: Therian Description: An ancient race of creatures who lived in Lemuria, an Atlantis equivalent of Indian Ocean, during the Jurassic Period. They were hermaphrodites reptilians who reproduced by laying eggs.

Sprite taken from Kyuuyakyu Megami Tensei

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deity Ninurta

Name: Ninurta Race: Deity Descritpion: An Akkadian god who battles in a fight the bird-like monster Anzu. Defeating him and the other monsters lets him to return the Tablet of Destiny to his father, Enlil.

Sprite taken from megatenktool

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deity Amon-Ra

Name: Amon-Ra Race: Deity Description: An Egyptian god revered in Egypt as a solar deity who created himself and everything. He was worshipped in Eliopolis as Ra and in Thebes as Amon.

Sprite taken from Shin Megami Tensei If…

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Avatar Anubis

Name: Anubis Race: Avatar Description: The jackal-headed god of Egyptian lore. He weighs the hearts of the dead to determine their final destination. He is also associated with embalming, and was able to rebuild Osiris’ body when it was cut into pieces by the evil god Seth.

Sprite taken from Shin Megami Tensei If…

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herald Aniel

Name: Aniel Race: Herald Description: The angel of beauty. His name means “the grace of God." He is commonly associated with Venus. His duty is to fasten the bonds of love between young men and women.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genma Kama

Name: Kama Race: Genma Description: The Hindu god of sexual desire. He looks like a young, handsome man on a parrot. He uses honeybees as his string and shoots arrows tipped with flows. By the gods’ request, he shot Shiva, but Shiva was angered and burned him with his third eye.

Sprite taken from albert-the-impact

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vile Mammon

Name: Mammon Race: Vile Description: Demon Prince of Greed, Mammon is Hell’s ambassador to England. Its name translates to dishonest wealth and it is sometimes referred as a deity or as a personification of greed in people.

Sprite taken from Shin Megami Tensei If…

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vile Demiurge

Name: Demiurge Race: Vile Description: An imperfect god of Gnosticism who created the material world. According to Gnostics of the Roman Empire, the Demiurge proclaims himself as God; when Adam and Eve gain “knowledge,” he cast them out in anger. The Demiurge wishes for the souls of humans to be trapped in the material world forever.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Famed Yoshitsune

Name: Yoshitsune Race: Famed Description: A Japanese general of the Genpei War near the end of the Heian era and start of the Kamakura era. His bold ingenuity and ruthless skill with a blade are still praised in Japan today.

Sprite created by opan_poon

2 notes

·

View notes