A silent reblogger that follows many fandoms. OTPs include Clexa, Victuuri, Johnlock, Hannigram, Drarry/ Dramoine, Destiel and Villaneve. I also post and reblog LGBTQIA+ - postive and humorous content. Oh, and i LOVE puns. Saya | INTP | Not straight |

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

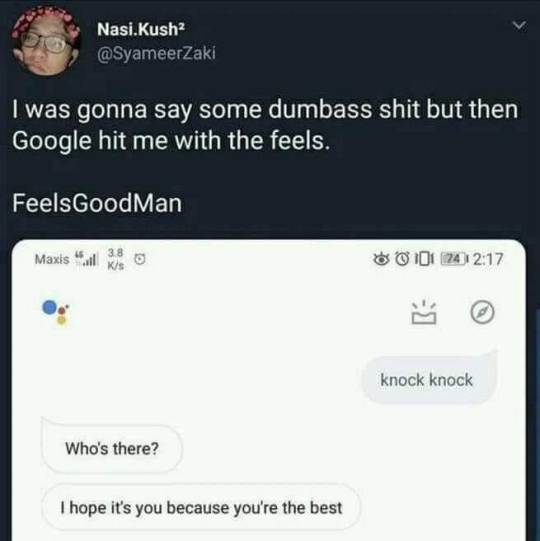

Photo

Which of these wholesome Memes are your Favourite? :)

Follow @memeuplift for more wholesome memes

91K notes

·

View notes

Text

i hate when people make fun of the "do yoga go for a jog drink water eat healthy get 8 hours of sleep" advice for mental health. theyre like OH THANKS IM CURED when the sentiment is not a CURE but an IMPROVEMENT i promise you if someone drags you out of your bed and forces you to go for a mile run you will ultimately feel better than if you stayed in your depression hole of a room covered in food containers and clothes on the floor for another 72 hours i PROMISE U. its not a cure but it is a step in the right direction with clinically proven benefits i say this as someone diagnosed w major depressive disorder stop being so cynical u have to actively engage w trying to get better

32K notes

·

View notes

Link

In the essays my students write, I have begun to notice a common pattern. They are structured almost like Aesop’s fables. A moral seems necessary at the end — a kind of wrapping up, whichever way one chooses to look at it, like a prayer of gratitude after a meal, or an antacid tablet to aid the digestive process. Occasionally, I notice this in their poems as well, how the concluding lines must justify the existence of the lines preceding them. I have begun calling it “moralitis.” Without a text’s display of morality, we seem to be at a loss about how to justify its existence.

I offer these summaries as an outsider. I wasn’t born in America or England, and I wasn’t a participant in, or even a contemporary observer of, Anglophone literature departments. I am a postcolonial citizen reading the white world reading.

I notice what has been well-documented: How the creation of “area studies,” its support coming from espionage funds of the American government, led to the incorporation of literatures from these unknown cultures into white literature departments. I use “white” in the most matter-of-fact, self-evident way, without anger. That was what it was, a crowd of white writers, primarily male, squatting on syllabi for decades. They had written about things that struck their fancy: elephants, women, mountains, wars, a cup of tea, a day in the life of an unremarkable person. The syllabus-makers had legitimized their wandering. It was all right, the white writer could write about anything.

The expectation of the nonwhite writers was different. They were to be tour guides to their cultures, burdened with satisfying the intellectual curiosity of the white world. As Amit Chaudhuri wrote in his essay “I Am Ramu,” published in n+1, “The important European novelist makes innovations in the form; the important Indian novelist writes about India. This is a generalization, and not one that I believe. But it represents an unexpressed attitude that governs some of the ways we think of literature today. … The American writer has succeeded the European writer. The rest of us write of where we come from.”

In India — where I now teach in the English and creative-writing department at Ashoka University, about 45 kilometers from the capital city of New Delhi — what began with Salman Rushdie and Amitav Ghosh and Vikram Seth performing their roles as researchers for this new reader soon turned into a habit. Rushdie had tried to bring the linguistic energy of a whole culture into his representation of the Indian nation; Ghosh a Stephen Greenblatt-influenced understanding of history into the historical novel; Seth a sentimental appraisal of an India that had now disappeared. They were ambassadors of the Indian nation, often thought to be “representing” India just as artists and performers represented it in Festival of India programs abroad.

This wasn’t, of course, what Seth and Ghosh and Rushdie had set out to do; it was just how their work had been appropriated by this new and foreign readership. At the same time, any writer — or any text — that did not fulfill the purpose of national ambassador risked being ignored or rejected by the academics — whether in India or abroad — who were designing courses about postcolonial Indian literature.

The consequences of this are far-reaching. I looked at a sampling of English-literature question papers in Indian universities, primarily in the country’s provinces, where an American understanding of Indian writing has been imported without any skepticism or unease — this despite professors teaching courses on power and imperialism. Courses have titles like “Indian Writing in English,” “Postcolonial Literature,” “Indian Literature in Translation,” “Commonwealth Literature.” The questions asked of the students are revealing. “Analyze Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines as a critique of the nation-state”; “Write a note on Velutha as a Dalit character in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things”; “Discuss Things Fall Apart as a postcolonial novel.”

By contrast, in the same departments, William Blake was being studied as “a precursor to the Romantics,” W.B. Yeats as “the last Romantic,” John Donne as “a metaphysical poet,” Virginia Woolf as “a stream-of-consciousness novelist,” and so on. If the contrast in the pedagogical approaches to the “third world” literatures and Euro-American literatures is still not evident, one can just jog down to the early British literature paper, and then to the Renaissance.

Postcolonial texts seem to have two jobs in these syllabi: They either negatively illustrate some form of moral or social misconduct, or they positively represent a “marginalized” culture or geography. Ideally, they do both at once, often in the manner of a Live Aid concert. The genre chosen for such illustrative purposes is most often the Indian English novel and, occasionally, the Indian novel in English translation..

While academics often see themselves as correcting the oversights of mainstream publishing, in this case, the two have colluded, even if unconsciously. Just as Indian professors feel a responsibility to assign “representative” texts, so within Indian English publishing, editors and publishers — beneficiaries of various kinds of privilege — have felt a moral responsibility to present and represent those they considered left out of their understanding of literature. That category included the Dalit, the Adivasi tribes, occasionally women. To publish these “unknown” and “unheard stories” — phrases that attend many of the blurbs of books about these cultures and people — is their version of affirmative action, almost akin to wearing hand-loom textiles to register their support for the poor weaver.

This enterprise has had consequences besides the intended ones. The “Adivasi” and “Dalit” writers these publishers championed became just that to the reading public: one picked up a book by such a writer to become a better person. Juries giving prizes followed the same path: By giving a literary prize to someone they had identified as a subaltern, they were in fact trying to give the prize to the community the writer came from. This is the neoliberal’s version of the subaltern-studies project.

I have heard from some of these writers about their dissatisfaction in being read as Dalit writers alone. Manoranjan Byapari, for instance, tells me that, although he has benefited from the largess of intent, he and others want to be read as writers, like upper-class and upper-caste writers are — not given attention solely because of their status as disadvantaged. It is not difficult to see that this was a mimicry of what had happened in the West: the Indian writers’ responsibility to represent their nation had metamorphosed, here, into “marginalized” writers’ responsibility to represent their “local culture.”

Like the soldier fighting for the country, these writers are seen as fighting for their culture. (This attitude also explains why translation, a field ignored for decades, has suddenly become a moral mission — we must bring the “underrepresented” into the range of vision, even if it is only the range of vision of the English-reading world.) Meanwhile, choosing what books to read becomes itself a moralistic enterprise, a form of atonement. One must read postcolonial literatures to pay the guilt tax. It is a reading toll that the student of the white-literature syllabus is not asked to pay.

But the proliferation of readers who seem to have become addicted to paying this tax has created a new kind of marginalized literature: literature that does not serve the didactic purposes of the postcolonial survey course. For one thing, the postcolonial-literature syllabus continues to remain parasitic on the novel — it is as if our histories could only be held in the form of the novel, usually a fat novel, its girth approximately proportionate to the size of the country. The poem and the essay have been rendered minor forms here. Fragmentary and whimsical in nature, personal and private in style, they offer no assistance in the information-supplying service that the postcolonial syllabus is expected to perform. The few poets who are studied, if at all, have been given a place on the syllabus for their founding-father status. Unlike the novel, where new work is regularly called for duty on the syllabus, contemporary poetry (say, Indian English poetry) might be imagined to have gone extinct.

The same question should be asked of the postcolonial syllabus. While the moralizing mission might appear admirable, these courses ignore all literature that does not fit its agenda. What else explains the utter absence of comic novels in the postcolonial course? How else to explain why Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s novels, particularly Aranyak, are not taught? Or why Amit Chaudhuri’s novels, with their life-loving energy, do not find a place here? Or why stories and novellas about provincial life, such as we find in the magical writing of R.K. Narayan, have not yet been included? Literature about the moment, about the everyday, is rejected: Comedy, laughter, pleasure — the postcolonial subject must not be seen partaking of these contraband things. The syllabus often reminds me of what our hostel matron used to say: Don’t smile and show your teeth when praying.

Here is the space where the syllabus remains to be decolonized — not through substitution, but addition. A course on British modernism will include a novel or two about a day in the life of a white man or woman, such as we find in James Joyce’s Ulysses and Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. But a young Indian student’s life on a day in July — masturbating, thinking of becoming a “famous poet,” walking around London with his uncle, eating at a restaurant and fighting with him, as we find in Amit Chaudhuri’s comic novel Odysseus Abroad — is judged too self-indulgent for a postcolonial course, even as it is not hard to see that this life in the novel, if anything, is the postcolonial subject’s condition.

What I am seeking is for the postcolonial-literature reading list to be liberated from its current status as “minor literature.” I do not use this term like Deleuze does, but rather to describe the sense within English-literature departments that these are to be studied as Ur-manifestos and histories of repression and suffering, and that all other kinds of writing are to suffer the same fate as banned literature: to remain ignored and unread. A course on Modernism, for instance, should include writing and art from non-Western cultures, where books exist side by side, related by temperament, aesthetic, or form, and not because of a United Nations idea of representation.

Literature in the postcolonial syllabus should surprise the student, not just confirm and illustrate “theories.” This, too, should be part of the decolonizing-the-syllabus mission: to dismantle the binary between postcolonial writers as content writers and Western writers as experimenters with form. Only then can we begin to address the “moralitis” of my students, which, although it might seem at first harmless, or even praiseworthy, turns out to entail a troubling indifference to pleasure and beauty, to ananda (joy and delight), which is often the backbone of India’s modern literatures.

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

HES SINGING BACON PANCAKES DHDJDKDK

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

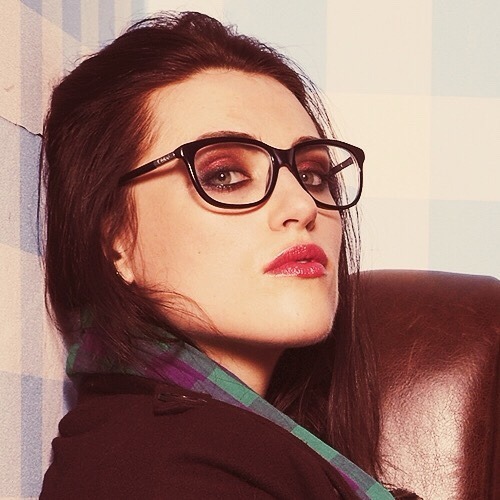

Katie Mcgrath kissing women again

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've already done Katie in suits, Katie kissing women, Katie being sexy, Katie being cute. But something was missing. So, here it is. Katie and glasses

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

So I've done Katie in suits, Katie being sexy and Katie kissing women. It's time for Katie being cute AF

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

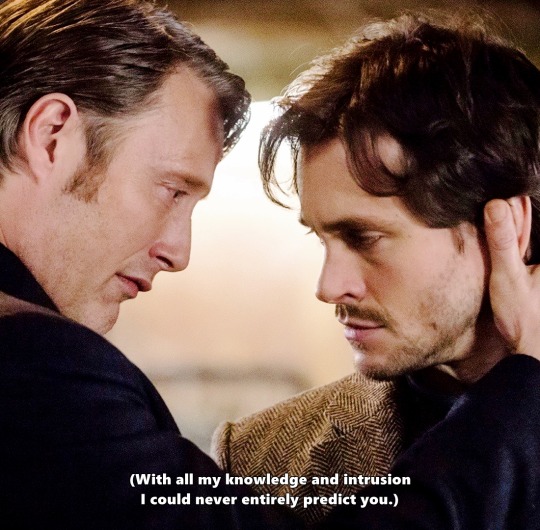

My favorite thing about the Hannibal fandom is that it's like 15% percent normal fandom content and 120% of insane fuckery that will make me scream laugh into my pillow at 12:39 am.

Case in point:

Like..... I know ye's do it because of the pain,,,, thank you?

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

alright alright ALRIGHT hannibal lecter is canonically in love with will graham and while surely this is a net loss for the lgbt community im still popping bottles

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

i am SCREAMING at this. Not only did he only fuck Alana so he could have an alibi he also straight ass told her that their sex was somehow about........ WILL? LIKE? There was NO need to say that NOT ONE SIR not one.. Not ONE REASON IN SIGHT to make this about Will and yet this bitch couldn't keep it together for 18 seconds

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

television’s hottest show is “hannibal”. located in the pantry of an aristocrat’s townhouse, this homoerotic nightmare is the creation of a middle aged gay man with trauma flashbacks, bryan fuller, who finally answers the question “what am i watching?”. this. show. has. everything. seven stray dogs of varying breeds, a social worker inside a horse, gillian anderson, a pig carrying a human fetus, and human origami. (whats human origami?) its that thing where, like, you fold up a dead body into the shape of an anatomically correct heart to confess your love.

7K notes

·

View notes

Photo

You’re right. We are just alike. You’re as alone as I am. And we’re both alone without each other.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

i want everyone to know that book hannibal lecter is like the funniest fucker alive

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992) / HANNIBAL, 2x10 ‘Naka-Choko’ (insp.)

7K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hannibal & Killing Eve + parallels

6K notes

·

View notes