Presented by the Collective Formerly Known as the DC Chapter of BYP100

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

If you’re on the physical self guided tour, check out our Google Map with these locations:

William Dorsey Swann (1114 F St NW, where Swann used to throw Balls)

Lucille Diggs Slowe (1256 Kearney Street in NE, home shared with Mary P. Burrill)

Mary P. Burrill (101 N St NW, Dunbar High School, where Burrill was a student and later on, a teacher)

Alain Locke (2441 6th Street NW, Howard University Dept. of Philosophy, where Locke was chair)

Protest Against Police Entrapment (US Marine Corps Memorial, Arlington VA)

Enik Alley Coffeehouse (alley near I St and 8th St NE)

Rayceen Pendarvis (1640 Rhode Island Ave NW, taping location of the Ask Rayceen Show)

First Black Lesbian and Gay Pride Festival (2500 Georgia Ave NW)

The Clubhouse (1296 Upshur St NW)

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

William Dorsey Swann

Dates: roughly 1858 – unknown

Audio available here.

Known to their* friends as “the Queen” William Dorsey Swann presided over a culture of Black underground drag balls in DC during the 1880s. Swann was born enslaved in Maryland and lived through the Civil War, after which they moved to DC as a free person. At Swann’s balls (held at 1114 F St NW), many people assigned male at birth dressed in “women’s clothes” and sang, danced, and participated in competitions, like the popular “cakewalk” where winners would win a hoecake or similar dessert. Two of Swann’s siblings (both also assigned male at birth) attended Swann’s balls dressed in women’s clothing too.

Swann’s balls were frequently raided by the police. In January 1887 The Washington Critic reported on one such raid, and described ball-goers as wearing “low neck and short sleeve silk dresses, several of them with trains,” “corsets, bustles, long hose and slippers, and everything that goes to make a female’s dress complete.” During an April 1888 raid, a fight broke out after Swann attempted to prevent the police from entering. This fight is among the first known instances of violent resistance against police for queer freedom.

In 1896, Swann was convicted of “keeping a disorderly house” —coded language used at the time to refer to houses where sex was traded— for hosting balls. Swann petitioned for a pardon from President Grover Cleveland regarding the balls, but was denied. However, Swann’s demand is the first recorded instance of a legal and political action taken in the name of queer people’s right to gather freely and without suppression in U.S. history.

Swann’s balls were not the first of their kind. Balls had been going on in secret for years and invitations were spread by word of mouth. Occasionally, references to Black men arrested wearing women’s clothes would appear in newspapers during this time. These sorts of references are some of our only written archival records of the existence of this form of queer community.

Photograph courtesy of the The Nation

*Swann did not use they/them/theirs pronouns, and is referenced in news coverage by he/him/his pronouns. Because Swann lived during a time in which very different language was used to describe gender identity, gender expression, and sexuality, we have no way of knowing what terms Swann would have preferred for use today. To respect the gender expansive nature of Swann’s social life, we have chosen to use they/them/theirs pronouns to refer to Swann in this gallery.

59 notes

·

View notes

Photo

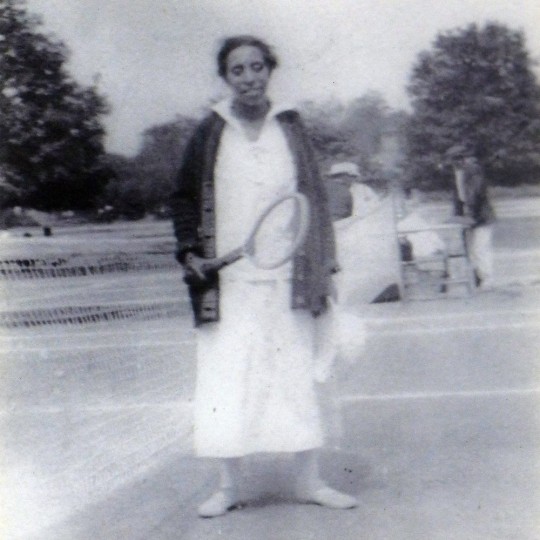

Lucille Diggs Slowe

Dates: July 4, 1885 – October 21, 1937

Audio available here.

Lucille Diggs Slowe was a pioneering Black American educator. Raised, and educated through high school in Baltimore, Slowe moved to DC in 1904 to attend Howard University. She graduated as valedictorian from Howard in 1908, and went on to begin her teaching career. The bulk of Slowe’s career was spent in educational institutions—first as a teacher in Baltimore, later as a principal in DC, and beginning in 1922, as Howard’s first Dean of Women. As Howard’s Dean of Women, Slowe championed expanded educational resources for women’s education and scholarship at the University. Her innovative work at Howard impacted the proliferation of women’s deanships at Black schools throughout the country.

1908, while Slowe was still an undergraduate at Howard, she became one of the original sixteen founders of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, the first Greek letter organization by and for African-American women. Black fraternities and sororities like AKA were founded with the intention of creating opportunities for Black college students to connect and build power in a segregated society.

A prolific member of Black organizations, Slowe helped to create multiple national groups designed to uplift Black women. In 1935, Slowe helped to organize the National Council of Negro Women. Later, became a founder and the first president of the National Association of College Women.

In addition to her career in education, Slowe was also an accomplished tennis player. In 1917 she won a national title at the American Tennis Association tournament— the first Black woman to win a major sports title.

For more than twenty years, Slowe was partnered with Mary P. Burrill, a Black American playwright and educator. They lived together, first in Northwest, and later in a house they purchased at 1256 Kearney Street in Northeast DC.

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mary P. Burrill

Dates: August 1881 – March 13, 1946

Audio available here.

Mary P. Burrill was an early twentieth-century Black American playwright and educator. Burrill was born in DC and attended high school in the city. For many years, Burril taught English, speech, and drama at Dunbar High School in DC, the same school from which she had graduated (although at the time of Burrill’s graduation it was called M Street High School). She was an impactful teacher and encouraged her students to write plays. Two of her students, Willis Richardson and May Miller, became pioneering playwrights themselves.

For more than twenty years, Burrill was partnered with Lucille Diggs-Slowe, the first Dean of Women at Howard University and one of the founders of AKA Sorority. They lived together, first in Northwest, and later in a house they purchased at 1256 Kearney Street in Northeast DC. In her early life, Burrill also had an emotional and possibly erotic relationship with Angelina Weld Grimké, who would later become a well known playwright and poet herself.

Burrill’s most notable works include The Other Wise Man (1905?), They That Sit in Darkness (1919), Aftermath (1919). Her plays touch on topics such as lynching, women’s autonomy, birth control, and poverty. Notably, two of Burrill’s best known works, They That Sit in Darkness and Aftermath, premiered in white-owned publications. Although there is no written indication of the reason she chose these publications, opportunities for a queer Black woman playwright to be published in the early twentieth century were very limited. They That Sit in Darkness was published Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review, and Aftermath in a communist publication, The Liberator. It is also worth noting that although Margaret Sanger (publisher of the journal that premiered one of Burrill’s best-known plays) was an advocate for access to birth control, she believed in eugenics, a set of ideas which many understand to be fundamentally white supremacist.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Alain LeRoy Locke

Dates: 1885 – 1954

Audio available here.

Alain LeRoy Locke was a Black American writer, philosopher, educator, and philosophical architect of the Harlem Renaissance.

Born in Philadelphia to parents who had been born free from slavery, Locke went on pursue his undergraduate studies at Harvard University. After graduating from Harvard, Locke became the first Black recipient of a Rhodes Scholarship (named after the English colonizer, Cecil Rhodes) and began graduate study at Oxford University. Locke became a professor at Howard University, first of English, and then served as the chair of the school’s Philosophy Department. As an educator, Locke encouraged his students to focus on Black American and African subjects in their works and to learn Black American and African history.

In 1925, Locke’s published The New Negro, an anthology of African-American literature including poems, fiction, drama, and music. Many consider The New Negro to be the inaugural text of the Harlem Renaissance. Locke’s vision for a Black future centered psychological and spiritual self-determination: he wanted Black people to be the authors of our own stories. He understood the arts—where Black people were free to imagine new futures—as the place from which to build a new political reality.

Locke championed Black writers such as Claude McKay, Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Ossie Davis, and Zora Neale Hurston, some of whom were also queer. Although he supported Black artists and writers of multiple genders, Locke was also known to be sexist and to frequently overlook women seeking his professional support.

Outside of his life as a scholar, Alain Locke was an openly gay man, although he never spoke publicly about his sexuality. Locke sought romance and sex with many of the artists and writers he mentored during the Harlem Renaissance. Relationships that were at times intellectual, romantic, intimate, and sexual became central to Locke’s contribution to Black life and culture at that time.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Protest Against Police Entrapment

Date: January 5, 1972

Audio available here.

On January 5, 1972, members of the Gay Activist Alliance in DC staged a protest against U.S. Park Police in Arlington, VA. In the months preceding the protest, police had arrested more than 60 people for “obscene and indecent acts” in parks— a coded way of speaking about queer sex. At the time, in Virginia and across the country, “sodomy laws” criminalized queer sex practices, particularly between people assigned male at birth. It was not until 2014, 10 years after such laws were ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, that Virginia repealed its “sodomy law.”

Many of those arrested in the park had been entrapped by police who were specifically tasked with arresting queer people engaged in outdoor sex (a common practice). Historically, police conducted undercover sting operations posing as people seeking queer sex, in order to find queer people and arrest them. Often these arrests used homophobic and stigmatizing language such as “indecent behavior” or “degeneracy.” In DC, police entrapment of queer people engaging in outdoor sex continues to this day. As recently as April 2019, more than 20 people were arrested in Malcolm X Park by U.S. Park Police for charges including “disorderly conduct” and “lewd acts.”

On January 5, 1972, a group of around 20 people from Gay Activist Alliance rallied on North Meade St. in Arlington. They marched toward the Iwo Jima memorial chanting and carrying signs. Some of the signs, like the one shown above, referenced the power of gay people to resist state violence and the urgent need to build politically. Others read statements like, “Don’t Expose Yourself, You May be Impersonating an Officer”— a reference to police entrapment. Six of the protestors were arrested for “demonstrating without a license.”

This protest was one of the earliest open demonstrations against police entrapment of queer people in the DC area.

Photo by John Bowden. Courtesy of the DC Public Library, Washington Star Collection © Washington Post.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Enik Alley Coffeehouse and the Sapphire Sapphos

Dates: 1982 – 1984

The Coffeehouse

Audio available here.

Enik Alley Coffeehouse, located near 8th and I St. NE, was founded by Ray Melrose, the then President of the D.C. Coalition of Black Lesbians, Gay Men and Bisexuals. Known simply as the Coffeehouse, the space was intended to be a social and cultural gathering place for Black and non-Black people of color to gather and create community. As one of the only places in the city where Black queers could regularly rehearse and perform artistic work, the Coffeehouse quickly became central to Black queer life in the city. Tucked in an alley, the Coffeehouse was small, although its size created an intimate environment for performance and socializing. In an interview for the book Queer Capital: A History of Gay Life in Washington, Larry Duckette, a frequent performer, described the Coffeehouse as “medicine.” “When I walked through the door, it was like the sun rose. It was wonderful. I never stopped going. I kept going back and back.”

Nationally acclaimed artists and writers, such as poet Essex Hemphill and filmmaker Michelle Parkerson, showcased their works-in-progress at the Coffeehouse along with many others in the community.

Although its years were short (the Coffeehouse lasted less than three years), many who regularly attended or performed in the space understand it as an enduring DC cultural landmark. Poet and actor Michael Saint-Andress described the cultural significance of the Coffeehouse like this: “This was the first time that we [Black queers] were out front and were sort of affirming ourselves and making known that we had voices and that we had a consciousness and that we had a connection to our communities and we were going to stay right where we were and be who we were.”

Photographs courtesy of the DC Rainbow History Project

Sapphire Sapphos

Audio available here.

Eventually, the Coffeehouse was leased to the Sapphire Sapphos, a “Third World* Lesbian social and political organization,” the first of its kind in DC, and served as an informal Black lesbian community center. Founded in 1979, the Sapphire Sapphos, held regular meetings at the Coffeehouse where they socialized and organized. According to Troi Graves, who served multiple terms as the group’s president, the Sapphire Sapphos were formed, because, “We came to the realization that we can’t sit back and let other people speak for us. We had the feeling that the Gay rights movement was perceived as, first, white, and second, primarily male. We wanted to say ‘hey look, there’s a whole lot of us out here.’”

One of the founding members of the Sapphos was Chi Huges, who also co-founded the Lamda Student Alliance at Howard University. Lambda Student Alliance (now Cascade) is the first, and longest running openly queer student organization at any HBCU.

Photograph courtesy of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

*At the time, the phrase “Third World” had a different meaning than it does today. Popularized by Franz Fanon, Black scholar and revolutionary, during the Cold War, “Third World” referred to the group of nations and peoples not aligned with the capitalist “First World” and the Soviet “Second World,” but who instead sought to realize an anti-colonialist alternate vision of the global future.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rayceen Pendarvis

Dates: Alive and well!

Audio available here.

Rayceen Pendarvis, also known as the High Priestess of Love, the Queen of the Shameless Plug, and the Goddess of DC, is an activist, entertainer, emcee, lifelong Washingtonian, and pillar of the DC queer community.

A self-described “gender-blender,” Rayceen is a child of the The Legendary House of Pendarvis, a chosen family of queer people of color connected to ballroom culture. In the 80s and 90s, Pendarvis focused energy specifically on raising awareness and funds to meet the needs of queer Washingtonians living with HIV/AIDs.

Pendarvis is best known for the Ask Rayceen Show, a monthly gathering and variety show held on first Wednesdays, which is now in its ninth season. Pendarvis was the first host of DC Black Pride in 1991 and later served as host of Capital Trans Pride. Pendarvis became the first openly gay ANC Commissioner and continues to be leader and elder in the Black LGBTQIA+ community.

6 notes

·

View notes

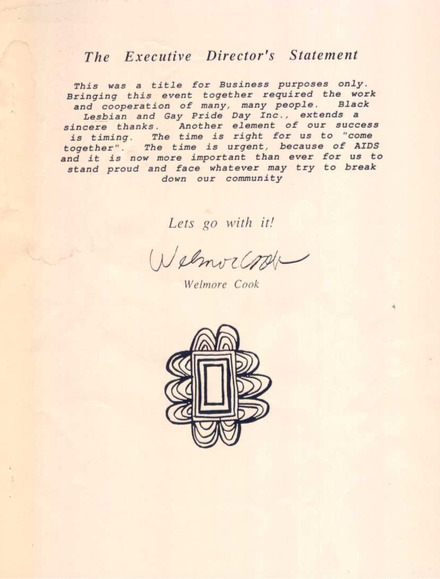

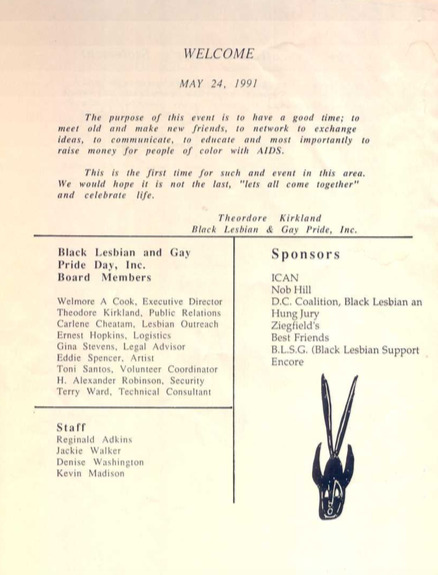

Photo

First Black Lesbian and Gay Pride Festival

Date: Saturday, May 25th, 1991 at Banneker Field, NW

Audio available here.

Organized by Metropolitan Capitolites, the first Black Lesbian and Gay Pride took place during Memorial Day Weekend in 1991. Memorial Day weekend was chosen because queer Black people regularly traveled to D.C. that weekend for the ClubHouse’s annual costume party. Noted emcee, activist, and entertainer, Rayceen Pendarvis, served as host for the festival. While this Pride festival was a celebration of joy, it also was a political declaration. "You know if you can't wear braids to work, you definitely can't be sleeping with the same sex," said Shirley Ripley, a legal secretary from Greenbelt, when interviewed about the celebration in 1991. Black queer people, then as now, were articulating the ways that anti-Black racism, homophobia, and sexism interlocked as forces of marginalization in their lives.

At the festival, safety precautions were taken, such as discouraging cameras and choosing a location that was up on a hill, enclosed by a fence, and had multiple entrances and exits. Despite persistent discrimination on the grounds of race and sexual orientation, folks came together for joyful celebration and community.

The festival not only raised money to support services for people living with AIDS, but also raised visibility for the Black queer community in DC. The festival marked a place for Black queer people to seek safety and comfort. For the often racist queer community, the sometimes heterosexist Black community, and the broader Washington D.C. community, the first Black queer Pride was a statement that queerness and Blackness ought to celebrated together.

Artifact courtesy of the DC Rainbow History Project

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The ClubHouse

Founded in July 1974

Audio available here.

In July 1974, the Metropolitan Capitolites, a social club for Black queer Washingtonians, selected 1296 Upshur St, NW as the site for its new nightclub venture: the ClubHouse. The ClubHouse was the third, and most successful, dance club project of the Metropolitan Capitolites, one of DC's earliest gay-oriented social clubs, that hosted house parties and then clubs as an alternative to discriminatory white gay bars.

Not only was the ClubHouse a hub for black queer life in Washington DC, but it also launched community-rooted responses to the early AIDS crisis. DC black gay activist Rainey Cheeks managed the ClubHouse in its early years. When he began noticing that some of the members had become sick and were no longer able to attend the ClubHouse, he started raising money from the club proceeds on Tuesday nights for members of the community who were unable to make rent or work. He also organized people into buddy systems, pairing club members who were ill with people who could help manage everyday tasks. He was also known to send limos for club members who were too ill to make it to the ClubHouse on their own. The club trained and employed a generation of DJs who carried the DC version of house music – a style of electronic music that arose in the 1980s, particularly in African American, Latino, and gay communities – to urban centers around the nation.

Photographs courtesy of the American Historical Association and the National Parks Service.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Essex Hemphill

Dates: April 16, 1957 – November 4, 1995

Audio available here.

Essex Hemphill was a Black American poet and activist. Hemphill is best known for his writing on Blackness, gay life, HIV/AIDs, Black families, and was central figure in DC’s art community during the 1980s. Born in Chicago, Hemphill was raised in Southeast DC and eventually attended both the University of Maryland and the University of the District of Columbia.

His collections of poetry include Diamonds Was in the Kitty and Some of the People We Love (1982), Earth Life (1985), Conditions (1986), and Ceremonies: Prose and Poetry (1992) for which he won National Library Association’s Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual New Author Award. The fact that Hemphill’s writing specifically examined his lived experiences as a Black gay man was particularly influential and impactful. Hemphill became an important contributor to literary and artistic discourse during the years he was active. He edited the 1991 anthology Brother to Brother: New Writing by Black Gay Men, a project which had been concieved by his late lover Joseph F. Beam, that highlighted the work of contemporary Black gay men’s writing. Anthologies like Brother to Brother have done important cultural work toward establishing pathways for Black queer writers to recieve recognition, and for readers to access stories that reflect them.

In 1982, Essex Hemphill, Larry Duckett, his close friend, and Wayson Jones, his university roommate, founded the spoken word group called "Cinque," which performed in the Washington D.C. area. When Joseph Beam, Hemphill’s friend, lover, and fellow author, passed away from complications related to AIDS in 1988, Essex worked with Joseph’s mother to publish a sequel to an earlier collaborative project, In the Life. Hemphill said in an interview that the anthology “was produced in the ‘context of confronting AIDS and the death around us. It’s almost like a fierce resistance that says, ‘Before I die, I’m going to say these things.’’”

Hemphill passed away in November 1995 due to complications from AIDS.

Photographs courtesy of the DC Rainbow History Project

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ivy Young

Dates: Still Active

Audio available here.

Ivy Young is a Black activist, feminist, and political organizer based in DC.

In the early ‘80s, between ‘82-’85, Young was a staff member at Roadwork, a women’s production company that promoted the art and music of many queer women and women of color. Roadwork produced an annual music festival in Takoma Park, Maryland, called Sisterfire, which provided a platform for women and lesbian artists to share their music in community. Young helped to produce Sisterfire in 1984 and 1985.

Young is best known for her work with the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force’s Families Project. In 1989, Young became the first leader of newly-developed Project, where she spearheaded advocacy on legal parenting rights for queer families, domestic partnership benefits, queer adoption, employment and insurance benefits, and the ability for queer people to make medical and legal decisions on behalf of their partners. The NGLTF Families Project worked at the national, state, and municipal levels to advance legal protections for queer partnerships and families. At the time the Project was founded in 1989, only six cities across the U.S. had any domestic partnership legislation in place.

Ivy Young went on to become Director of NGLTF’s Creating Change Conference, a yearly gathering of queer activists, organizers, scholars, and students for skill-building and community.

Photograph courtesy of the DC Rainbow History Project

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Colevia Carter

Dates: Alive and well!

Audio available here.

Colevia Carter is a DC-based community organizer, activist, educator, poet, and musician. Carter moved to D.C. in 1975. Shortly thereafter, she began living in a group house in Mount Pleasant, where she discovered vibrant lesbian community. An active contributor to artistic life in the District, she played percussion in a women’s band called “Hysteria,” performed poetry at the DC Women’s Center on M Street, contributed to the anthologies Lesbian Culture: the lives, work, ideas, art and visions of lesbians past and present and The Colors of Love: The Black Person’s Guide to Interracial Relationships, performed in Chasen Gaver’s Standing in Shadows, and was a member of the Lesbian Feminist Network and the Sapphire Sapphos, where she served as political action committee chair. In the 1970s, she was also affiliated with the DC Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays, was an executive board member of the National Association of Black Lesbians and Gays, and participated actively in the National Third World Lesbian and Gay Conference held at Howard University in 1979 — a major moment of visibility and power building for queer people of color in DC.

Carter was active in the fight queer life against HIV/AIDS. In 1982 and 1983, when Carter became aware of the disease that would later become known as HIV/AIDS, she developed educational programs for incarcerated people in Lorton, Virginia to raise awareness about the disease. In 1984, she organized the first D.C. conference on Women and HIV/AIDS. She worked as an outreach coordinator to intravenous drug users and people in the sex trade, providing stipends to volunteers for participation in street-based research. She also became the co-chair of Whitman-Walker Clinic AIDS Education.

In 1982, around the same time as she began her work on HIV/AIDS, Mayor Marion Barry appointed Carter to the D.C. Human Rights Commission where she served for five years and was the first openly lesbian commissioner.

Photographs courtesy of Tagg Magazine

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juneteenth: How We Get Free - a Celebration of DC Black Queer History Through a Self-Guided Tour

This Juneteenth, BYP100 DC is celebrating how we get free through our queer ancestors and elders. This blog showcases a selection of the people and places who through art, activism, scholarship, and by simply existing, have made our Black queer lives possible in Washington, DC today. Like any attempt at telling history, this blog is incomplete. We have lost so many Black queer people to the violence of enslavement, the state, colonialism, the police, heterosexism, and transphobia. There are so many stories we have lost to the exclusions of racist and homophobic archival practices. We may never know their names but we recognize their presence in our paths and stand in gratitude in their legacy.

We want to offer a self guided tour. In this space that we are in, with so much going on, it is important for us as Black folx to disconnect and take care of ourselves. We make this offering in celebration of the people and places that survived and thrived on this land, and in doing so, built the possibility for us to imagine the liberated Black futures we fight for today. We tell these stories to enable new lives and new ways of living for our collective future.

Check out our playlist for an audible version of our tumblr posts!

28 notes

·

View notes