Text

Final Doc and Essay

youtube

Nichols defined observational documentary to observe “lived experience spontaneously”, a form of film where an audience could view life as it occurred without direction or script, pure happening. To remove control over staging, arrangement, composition, and the social actors meant to allow spontaneity. My choice for doing an observational documentary came only in the moment of filming. I had originally intended to do a participatory documentary, but once I began filming, I could feel that the space could probably be better captured as an observer rather than a participant. So, as I “[retired] to the position of observer…”, I could also reflect on what we learned during the course.

As documentarians we should be aiming “[to call] on the viewer to take a more active role in determining the significance of what is…done.” Nichols gave us these beautiful pointers and we have seen it practiced many times. In Grey Gardens (1975), we caught the power of observational documentary; the social actors oversaw the film and were given the power to share their voice as they naturally are. The camera felt like a fly on the wall, observing the women as they lived their lives. Even at times while the women are directly speaking to the audience, the camera will cut between scenes viewing other parts of the house, such as when the cats are being described. We hear the elder Edith Beale describe her love for cats while we get shots of the cats as they lounge and enjoy their freedom with the two sisters.

Another scene in a very observational format was with the small fire in a corner of the house, where the Beales are heard crying out to one another about the fire, speaking to the cameramen and crew and asking if they are crazy for simply observing the situation. But this attests to the job of observational documentary; the crew is a separate entity meant to film the subjects and situations but never interfere. The use of the observational format was highly effective in this case, as it made the audience recognize the sisters’ loneliness. By observing and listening without a chance to voice their own opinion or affect their lives, the audience is left to empathize. I felt that I wanted to create deeper connections to the emotion of what I was filming rather than giving the audience a defined theme to follow. This is also reflected in the title I chose for the film, “At the End of the Night”.

I originally had planned to film the closing of an event and the thoughts of the staff who had worked it, including myself. I was planning on interviewing and guiding a conversation into the ideas of fulfilling customer service demands after long hours of working. In preparation for that I tried filming some filler content, the end of the night and such, but I found myself becoming fascinated by what I captured. The emotions I could see by the actions my coworkers performed and their interactions with the last straggling guests. I even found space to give moments for those stragglers to shine in their final moments of blissfully enjoying the last seconds of the party. I became absorbed in the capturing of those moments and quickly moved into an observational format, attempting to capture the viewpoints of the workers and the attendees and how they reflect with one another.

I made this choice also thinking of my audience, students who most likely worked in jobs like mine, where they must perform services for others and often late into the night. It would be a film that captured the best moments of those nights, where the atmosphere is toning down and the people involved are also releasing their stress from the day. I wanted the tone of the film to feel like the moments filled with the laughter of coworkers followed by the collective grateful sigh that the night is over. I also waited to ask permission to use the social actors in my film after I had recorded them, letting them know that I was very willing to part with the footage if that made them more comfortable, but after having viewed said footage, each participant gave their consent and many stated that they were glad they hadn’t been warned of being filmed because they enjoyed the capture of such raw moments of living.

Observational documentary in my opinion is meant to bring the audience into the shoes of the social actors involved. They are meant to connect in an emotional manner, empathizing with the experience of the film and making personal connections to it. We as documentarians must capture raw moments for the audience to have that opportunity; and we as an audience must view the film as an experience rather than a retelling, searching for the connections to our own lives. Observational documentary transcends time periods and trends in film work, as it is a way for us to share film in a way that we experience life naturally, through observation. Through every period there are events that will occur, normal and ordinary people who live like us in lives completely different from ours. And as observational documentarians it is our responsibility to give the world the chance to enjoy those connections, living spontaneously with others and determine the significance of each human story.

0 notes

Text

Online Response 5

I am Not Your Negro (2016)and Paris is Burning (1990) hold similarities in their documentary style. Both films place interviews and observational footage together to create an experience for the audience to become more personalized with the portrayed social actors instead of viewing what occurs as akin to a history lesson. Both films also share a choice in depicting their chosen messages over a longer period of time, with I am Not Your Negro including footage beginning from the 1960s, Paris is Burning is a compilation of footage captured over many years. By doing so, both films portray a growth for their social actors beyond a single circumstance and can capture the development of their voices and situations. This is where the films can connect to Ta-Nehisi Coates’ book.

In Between the World and Me, Coates attempts a personal record of his own thought process and development when in consideration of Black voices in America. He details his own personal experiences and interactions with American society and the effect those have on his next impactful moment of growth and how he continually develops into who he was by the time of finishing the book. This is very alike to both films, where they pass through a history of time, introducing social actors to follow, their circumstances and how they are affected through situations in their lives. They all exhibit growth and the impact that the society they interact has on their voices.

All three of these pieces can teach us much about Black and LGBTQIA+ voices. They all remind us of the humanity we are supposed to be sharing, to create connection and understandings between their struggles and our own. These pieces, I feel, are meant to establish empathetic connections between marginalized and overwhelmingly overlooked voices and the norm. They are meant to remind the audience to listen to voices around them and not just to those they feel alike to, because in the end, all humans share an alikeness in their lives and should therefore share similar standing in the power of their voices. But this isn’t the case and so marginalized voices must be sought out and empowered until they reach the same power as voices of the norm.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Online Response 4

Reflexive and participatory modes of documentary are quite similar in that they often include the filmmaker in the film. But they differ where reflexive documentaries tend to focus on themselves, the filmmaker, and the act of making a film. Meanwhile, participatory documentaries make an attempt to explore an outside object with the filmmaker an active participant in the film.

Films like Sherman’s March (1986) follow the participatory format. Participatory films are often characterized by interview sequences that mark key moments in the film, these moments where the filmmaker becomes a social actor to move the fil along in conversation. Nichols adds that participatory is when “we expect to witness the historical world as represented by someone who actively engages with others, rather than unobtrusively observing…” As Ross Mcelwee attempts to focus on events of the American Civil War he places his own troubles and search for romance into the film, making him a very real social actor who still moves the film in following his original goal of documenting historical events while being human himself before the camera and participating with the subjects of the film in behalf of us, the viewer.

Reflexive mode on the other hand is what Nichol’s calls an “intensified level of reflection”, where the focus goes from filmmaker with social actors, to filmmaker with viewer. Reflexive documentary attempts to represent how the world is represented and what gets represented, and accomplishes this by focusing on the actual filmmaking process by allowing the viewer into the process and choices made by the filmmaker. We have seen two form of this in Surname Viet Given Name Nam (1989) and Man with A Movie Camera (1929). In the former we were given experiences of Vietnamese women through interviews but were later revealed immigrants recounting responses from actual oppressed women in Vietnam. And the latter repeatedly places the editing room in view of the audience and compares the camera and its uses to everyday experiences. Both of these documentaries fulfill the demands of reflexive documentary as they move an audience to go beyond looking through documentaries to looking at what a documentary is.

These two modes, reflexive and participatory, are similar in the use of the filmmaker in their forms of storytelling. The filmmaker has taken on the role of social actor in both modes and openly influences the film and its focus, bringing themselves into direct conversation with the audience. And the differences between the two comes from the base way that the filmmaker is interacting with the audience. In participatory, the filmmaker speaks to a social focus in a sense of “I speak with them for us (the audience)”, allowing for a new perspective beyond observation. And in reflexive the filmmaker takes a chance to pull the audience into the process and ask them what it mean to make a documentary, a conversation meant for viewers to begin to look into the documentary itself rather than the social actors or instance it is covering.

0 notes

Text

youtube

Doc mode 2 – Reflexive Documentary

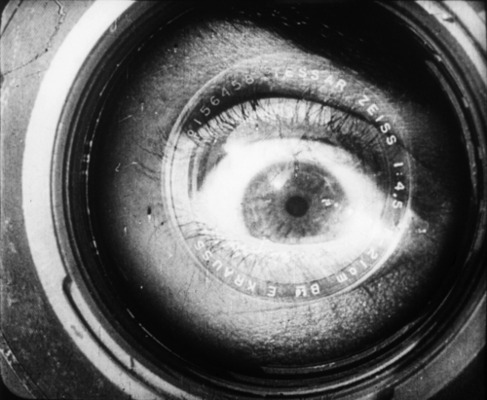

For inspiration on this documentary, I tried to capture a modern take on Man with a Movie Camera (1929). To do so I took inspiration from the scenes of the woman blinking and the shutters opening and closing. It was a form of connecting human to inorganic, and later the eye to a camera lens. I took that idea and went with it, by cutting with myself being replaced by the camera, then only seeing what occurs through my phone screen or camera lens, I felt that it showed a replacement of our own eyes with the camera technology we have today. The control we’re allowed over our vision and the way it can enhance our experiences. It was great to film at an unexpectedly rainy time, it allowed a choice to leave the natural noise as a backdrop throughout so as to keep the contrast of human vs. technology as the viewpoint becomes solely technological.

Directly pertaining to the reflexive, I attempted to make the camera feel like the viewer, forcing the audience into the technology perspective of filming, and how it is near impossible to tell what device filmed certain scenes unless there are direct markers setting the scene. The documentarian can be found anywhere now, with access to a cellular device one can create beautiful documentaries on their own. The camera has become a universal tool and it can allow us to reflect on what makes a film shot on a film camera different from filming on a smaller and more “inferior” device? Is it solely a social preference? This short piece hopefully allows space to discuss with the audience that it is just as well done through a phone as it is done on a camera to film. With the correct preparation, a documentarian can piece together whatever masterpiece they can dream of.

This also could bring to question another question. If we all can be such documentarians, what makes some great? Could a great documentarian take a cellphone and make a documentary that will still impact us the same as if they used a film camera? What techniques make a documentary “good” and can those be used with any device with a camera on it? By having the documentarian (myself) only there to stand as a marker for where a camera would be placed, it allows the audience to recognize that humans still drive the power of the documentary. We have to be the ones who choose the correct angle and placement, because our eyes are still the purest “cameras” we possess. And using a camera is in many instances simply a means of recording what we do naturally on a daily basis so we may have the opportunity to share it with our fellow creators and with our audiences.

Reflexive documentary brings the filmmaker into the film so as to bring the audience into conversation with them and themselves about the filming process. The questions that come from filming in this mode are uncontrolled and can be completely different from what I even make a statement about. But, this mode of film is always a great way for documentarians to give out a conversation starter about filmmaking itself and await the audience response.

0 notes

Text

Online Response 3

When considering the Participatory and Reflexive modes, there are specific differences in the way they treat the subject, treat the audience, and the techniques they use for communicating a message. In a Participatory mode, the documentary is when the filmmaker has begun interacting with the subjects rather than passive observation. Reflexive documentaries bring the filmmaker to engage with the problems and issues of representing certain social and historical aspects and stories.

With the subject, in a Participatory setting, the subject is interviewed in many instances. The filmmaker guides a conversation and discussion on the chosen social topic and allows the subject space to personalize their experience to it. At times this can push for collaboration or confrontation, where the subject expresses gratitude or feelings of being attacked by the passive audience and active filmmaker. Our job as an audience in this instance is one of observation and personal conclusion-making, there is not much space for our involvement directly with the conversation but rather the creation of a space for sympathizing (and hopefully empathizing) with the subject. This is done through different techniques, one of which includes the tone of the filmmakers' conversation, it follows a formula close to: “I speak with them for you”. We see this in Sherman’s March (1986) as Ross conducts spontaneous interviews for two reasons, meeting women and thoughts on "Sherman’s March”. Ross even goes so far as to state, “As for me, I keep thinking that perhaps I should return to my original plan to make a film about Sherman's March; but I can't seem to stop filming Pat.” A clear example of the filmmaker's personal influence on the film and the use of interview techniques to drive conversation in the audience. This meaning they guide the conversation in our place for the audience to guide their own discussions on the topic later in a sandbox of sorts. The film has a created a defined area of conversation but it does invite the audience to participate amongst themselves on their personal connections following the film. Another technique is a style close to radio talk show hosts, where they invite conversation but are still left as the sole drivers of the conversation with the subject. This mode ultimately moves us to have the chance to see how the filmmaker’s involvement can directly influence and alter the given situation.

In a Reflexive setting, there are differences to these interactions from the Participatory mode. As for the subject, the Reflexive mode tends to move away from placing importance on the subject. The subject is still a driving force in the film, but it is immediately counteracted with some form of a peek into the actual filming process. The audience gets a direct glance into the “behind-the-scenes" and this changes the importance of the subject. Now our attention is diverted into reflecting on the meaning and influence behind a camera bringing us a pointed view of social situations. The audience is then directly affected beyond what the Participatory mode does. The audience must participate actively throughout the film and afterwards, they are told to consider the process and it influence on the film during the film The Reflexive mode pushes techniques used by other modes into a form that no longer focuses on what gets represented but how it gets represented. As declared by Minh-ha, it is about “speak[ing] nearby” rather than “about [or] with” the subject. In many instances the film will include shots of the editing room, so as to break the illusion of documentary observation and put the audience directly into the filmmakers' shoes and question how that affects the social message of the film.

Through these techniques and treatment of the subject and audience there are obvious differences between Participatory and Reflexive modes but both do the work of pushing a documentary to involve their audience beyond passive observation and discuss the message of the film amongst themselves.

0 notes

Text

youtube

Doc Mode Activity 1: Observational

In line with many other documentarians to practice observational documentary, according to Nichols, I filmed in a manner that observed “lived experience spontaneously”. By removing control over staging, arrangement and composition of the peoples filmed, the event was filmed spontaneously. The only thing I remained in control of was the camera angle, which had only one requirement, no faces would be clearly seen, to reflect on a general treatment of society on retail workers. Often overlooked and inconsequential to memory of the customer, retail workers simply pass their shift by, fulfilling their job until the shift change. This piece was specifically focused on the time of shift change, a hidden view of workers who were ready to change shift and the arrival of their replacements. Although I did edit the voices out of workers and business sounds, I did so with the intention of holding to my theme of overlooking workers, but I did use music that is played in the store itself, specifically the music played that day of filming as I felt it allowed for the audience to feel a part of the scene even though they are observing two workers. This does go against most observational films, which tend to follow persons as they are caught up in their own crises or a pressing demand and instead allows the audience to draw conclusions on the workers based purely on their body language and personal empathy to the situation. I think by doing this, I was able to do Nichols suggests and “[retire] to the position of observer… [to call] on the viewer to take a more active role in determining the significance of what is…done.” Although I did take liberty in some control of the film and did not simply film all I could observe as an active observer, I feel that this short film still fulfills the role of an observational film, especially when considering the implications of such documentaries on audiences. I created a film that allows the audience to actively participate and avoided interaction with the persons involved, leaving space for open interpretation based on individual empathy, experience and understanding.

0 notes

Text

Doc Mode Activity 1: Observational

In line with many other documentarians to practice observational documentary, according to Nichols, I filmed in a manner that observed “lived experience spontaneously”. By removing control over staging, arrangement and composition of the peoples filmed, the event was filmed spontaneously. The only thing I remained in control of was the camera angle, which had only one requirement, no faces would be clearly seen, to reflect on a general treatment of society on retail workers. Often overlooked and inconsequential to memory of the customer, retail workers simply pass their shift by, fulfilling their job until the shift change. This piece was specifically focused on the time of shift change, a hidden view of workers who were ready to change shift and the arrival of their replacements. Although I did edit the voices out of workers and business sounds, I did so with the intention of holding to my theme of overlooking workers, but I did use music that is played in the store itself, specifically the music played that day of filming as I felt it allowed for the audience to feel a part of the scene even though they are observing two workers. This does go against most observational films, which tend to follow persons as they are caught up in their own crises or a pressing demand and instead allows the audience to draw conclusions on the workers based purely on their body language and personal empathy to the situation. I think by doing this, I was able to do Nichols suggests and “[retire] to the position of observer… [to call] on the viewer to take a more active role in determining the significance of what is…done.” Although I did take liberty in some control of the film and did not simply film all I could observe as an active observer, I feel that this short film still fulfills the role of an observational film, especially when considering the implications of such documentaries on audiences. I created a film that allows the audience to actively participate and avoided interaction with the persons involved, leaving space for open interpretation based on individual empathy, experience and understanding.

0 notes

Text

Online Response 2

Act of Killing (2012) and Night and Fog (1956) depict the topics of war and genocide in similar and opposing ways, but both do so in a way that allows for them to evoke a sense of extreme discomfort and terrifying awe in the audience. Similarly, they both question the consequences of the events depicted, asking for responsibility. They also describe gruesome circumstances and show the locations that they occurred, proving the legitimacy by giving the audience a look into the location while being described the horrors. They do differ in their tone and depiction of the events greatly though. Night and Fog leans on past footage to accentuate what is presently shown while Act of Killing only relies on the presently filmed persons describing a very biased past.

In a similar fashion, both films question the accused. Act of Killing gives Anwar the microphone for almost the entire experience, allowing him to describe horrors, question his own sanity and morality and defend his choices. Anwar becomes our viewpoint and the consequences of his actions become complex. Night and Fog does this in a fashion of juxtaposition. It shows black and white and color footage depicting the horrors of camps against the victorious allies, newsreel footage recounts the rationalization of Nazi theories, intercut with color footage of the ruins. The contrast in both films, from voice to image, similarly leave the audience searching for responsibility to place, attempting to understand the dark events from different perspectives at once.

Location in both films gives them the power to evoke this search within themselves from the audience. A terrifying awe in the mere fact that these periods existed, the events occurred, the horrors are true. And a discomfort in the fact that it could happen again, it was not unusual circumstance, it was not extreme people, it was a mess of complications, well-timed circumstances and the right push that created these historical horrors. The audience is left to face the real locations and hear the true stories and consider what to do with that information. The messages of both films leave the audience wondering on the fragility of humanity and the painful immorality of it as well. These documentaries use powerful imagery to convey to an otherwise oblivious audience that horrors as great as these do not just occur, there is a buildup, and they can happen in any seemingly normal place and time.

The tone and depiction of events is differing though. Act of Killing has physical reenactments made by the killers themselves, even showing the process of them filming a recreation of their acts. Night and Fog on the other hand, uses simple cinematography of ruins mingled with solemn narration to give the audience a connection to the events. These differing techniques end up creating tones that push for similar audience interactions but through opposing means. Act of Killing carries a tone of insecurity, a sense of confusion by allowing the people we view as villains to share their stories in such a laidback and even almost heroic form. The villain is allowed to recount their tale with no fear of consequences and convince the audience of a deeper perspective on the horrors. Night and Fog carries a tone of solemn remembrance, giving historical inquiry and a search for purpose in remembering, the audience is still left pondering the importance of these events afterwards.

Both films points to the evils of being human but do so through opposing methods of a biased retelling and neutral remembrance. Similarly, they use depictions of real-world locations to evoke deep emotions from the audience, image juxtaposition and narration to also guide the audience to a message on the immorality of human beings. Both films are extremely well-done documentaries that utilize elements of the form to craft powerful films and strong audience receptions.

0 notes

Text

Online Response 1

In the 2012 documentary “The Act of Killing” there is an opening sequence that immediately strips the film down to what it is. It claims to be testimonials and reenactments of killings of communists by Indonesian gangsters that made them heroes to their fellow countrymen. By following Anwar Congo as he details the horrors he committed, the filmmakers give this man an almost heroic pedestal from where he can detail his acts of villainy. Due to the voice being given to him we understand that he is no true villain, as he states, “I can feel what the people I tortured felt. Because here my dignity has been destroyed, and then fear come, right there and then. All the terror suddenly possessed my body. It surrounded me and possessed me.”

Anwar has portrayed himself honestly to the audience and it creates a moral uncertainty in many viewers. Not in condoning the torture he committed, or the killings, but to acknowledge this man as human, a human who had a purpose and reason and feels the good in life just as any normal person does. This man is not inherently evil and that creates a difficulty to hate, rather his pain is understood, and his regret is sincere, and even more so is his national pride relatable to many, especially Americans.

What the filmmakers wanted to come from this film, whether that be justice for those murdered or a simple telling of the story, the film has done what documentary is meant to do, give a story built in our real life that feels as a creative treatment of actuality. Many might deny the truthfulness of it, and others will eb revolted but all will be affected in ways deeper than a fiction film can do, because documentary works in our own world and not in an imaginative one. As Anwar also states, “We can make something even more sadistic than... more sadistic than what you see in movies about Nazis. Sure, I can. Because there's never been a movie where heads get chopped off - except in fiction, but that's different - because I did it in real life!”

To make a documentary detailing the national pride gangsters felt while murdering countless of their self-proclaimed enemies, all while they make their own film about it is something poetic. It is an eye-opening experience for the audience and for our characters as well, where many begin to question their own decisions and lives. Some question if what they did was right, others question if they can keep their heroic standing after this, and others wonder why they did it at all. The audience is left to ponder these questions as well and ask themselves howe they feel towards such men. Is it understanding? Empathy? Disgust? Pity? All of these and more?

Anwar himself brings the documentary to a close by having a deep reflection on himself and his actions on a rooftop where he committed some of his most vial atrocities. This same man then recounts the stories while retching, all the while asking if he has sinned. Having played the victim of these killings in his own film, he had his own eyes opened before us, and the audience can conclude on their own opinions of the film and the persons portrayed. Perhaps the deepest moment of the film is in Anwar’s final questions before we see the dancers one last time. “Did the people I tortured feel the way I do here? I can feel what the people I tortured felt… Really, I feel it. Or have I sinned. I did this to so many people, Josh. Is it all coming back to me? I really hope it won't.” Regret is a universally understood emotion, and having that moment followed by a final scene of the dancers seems to drive home a theme of this documentary: offenders realize their sins only when they begin to explore feelings of guilt and regret.

1 note

·

View note