Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Users DO care about being tracked

With Big Tech's PR machine busy at work, the narrative has become quite popular that people don't care about privacy and the supporting "evidence" is readily at hand that individuals share readily all sorts of personal information on social media outlets.

Elon Musk, on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast in September 2018, pushed back when asked about the future of security and privacy, responding by asking the question, "Do people want privacy, because they seem to put everything on the internet?"

Of course, Musk's shortcoming here is that he is extrapolating a little too generously. In other words, sure, some people post personal information in public forums; but that does not allow one to conclude that all people disregard the value of their personal information.

The rubber seems to have (finally) met the road, with compelling data coming out that, sure, some people do care about the data.

Recent changes made by Apple to its iOS operating system have enabled users to opt whether or not they want to be tracked. The majority, and perhaps vast majority, of users are saying "No!" (According to Flurry Analytics, it may be that north of 90% of users are saying "track me not, thank you.")

Last week, when Meta (formerly Facebook) released its earnings, it explained the "headwinds" to its marketing engine that come with the changes Apple introduced. In its earnings call, Meta (transcript here) explained:

"we believe the impact of iOS overall as a headwind on our business in 2022 is on the order of $10 billion, so it's a pretty significant headwind for our business."

Time for a change in narrative?

via Blogger https://ift.tt/APeNMwE

0 notes

Text

CLO Credit Ratings Gone Awry

Co-authors Gene Phillips and Mark Adelson wrote the following article, which was published in the Fall 2020 edition of the Journal of Structured Finance (JSF); it is available in its entirety on the JSF's website at this link.

---

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a broad reach, spanning most sectors and industries. This distinguishes it sharply from the mortgage meltdown and the 2008 financial crisis, which were mostly confined to the housing sector and financial institutions, respectively. Collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), which were largely immune to the perils of the mortgage meltdown and the financial crisis due to their diversity among corporate issuers, find themselves exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rating agencies have been downgrading the speculative-grade loans that support these CLOs en masse: during the four-month period ending June 30, 2020, Moody’s downgraded the ratings of 755 speculative-grade borrowers, a full 31% of the speculative-graderated universe, across a range of industries (Moody’s Investors Service, n.d.). The industry sectors most affected are shown in Exhibit 1.

While the loan-level downgrades continue, the rating agencies are also downgrading the CLOs backed by the loans. Meanwhile, corporate defaults are already on the high end. As of the end of July 2020, S&P reported 98 year-to-date defaults, already surpassing the full-year corporate default tally for 2008, which reached 95 (Serino, Kesh, and Pranshu 2020).

This note focuses primarily on CLO ratings — but there have been oddities in the rating of residential mortgage-backed securities (“MBS”) during the pandemic as well.

While the credit rating agencies are actively downgrading speculative-grade corporate loans and outstanding CLOs backed by these loans, they continue to rate new CLOs at the same time. Their approaches to this tricky proposition, and their communications describing their approaches, give us pause. We find that they are: 1) not being transparent about how they apply their methodologies, 2) either not applying their methodologies or not applying them consistently, and 3) not being consistent in their deviations when they deviate from their official methodologies.

RATINGS DOWNGRADES AND NEW RATINGS

In an inauspicious report of May 2020, titled “How COVID-19 Changed the European CLO Market in 60 Days” (Ryan and Tamburrano 2020), S&P explained that the changes have come “in a sudden and marked way” and that the “wave of negative [corporate loan] rating actions has affected several sectors, geographies, and products.” Strikingly, S&P noted that “[m]arket challenges that existed before COVID-19, including high leverage ratios, EBITDA add-backs, and cov-lite loans, are causing speculation that this may be the perfect storm for CLOs.”

As of early June, Moody’s had placed 1,100 CLO notes on watch for possible downgrade. That amounted to 24% of all CLO notes by count and 7% by balance (Deshpande, Mogunov, and Chatterjee 2020). The rating agency stated, “Moody’s actions today follow the CLO actions Moody’s took on 17 April 2020, and are primarily prompted by a continuing decline in the credit quality of CLO portfolios as a result of economic shocks stemming from the coronavirus pandemic. Since April, the decline in corporate credit has resulted in a significant number of downgrades among the assets underlying some CLOs.”

The downgrading continues, but some of it has been tepid. When downgrading, Moody’s has often opted for only a single notch downgrade. For example, on July 1, Moody’s noted significant collateral deterioration in a CLO called Nassau 2017-II Ltd. The rating agency stated:

Based on Moody’s calculation, the weighted average rating factor (WARF) was 3764 as of June 2020, or 25% worse compared to 3006 reported in the March 2020 trustee report. Moody’s calculation also showed the WARF was failing the test level of 3022 reported in the June 2020 trustee report by 742 points. Moody’s noted that approximately 40% of the CLO’s par was from obligors assigned a negative outlook and 7% from obligors whose ratings are on review for possible downgrade. Additionally, based on Moody’s calculation, the proportion of obligors in the portfolio with Moody’s corporate family or other equivalent ratings of Caa1 or lower (after any adjustments for negative outlook and watchlist for possible downgrade) is approximately 30% as of June 2020 (Aeron and Ham 2020).

Nevertheless, despite significant deterioration, and in the face of a 30% exposure to Caa1 or lowerrated assets, Moody’s downgraded the Class C, Class D, and Class E notes by only a single notch, from A2, Baa3, and Ba3 to A3, Ba1, and B1 respectively. Moody’s affirmed the rating of the Class B at Aa2.

In late July, S&P downgraded 63 CLO tranches by an average of 1.2 rating notches. But 496 tranches across 287 CLOs remained on CreditWatch negative. As shown in Exhibit 2, data on the “S&P CLO Insights 2020 Index” reflected the weakened condition of the deals.

Meanwhile, the performance of CLOs is to a degree based on the vigor with which the rating agencies downgrade the corporate loans. In addition to default events, downgrades themselves can impact a CLO managers’ ability to trade assets, especially once they start to fail collateral-quality tests. With CLOs being so heavily laden with B-rated collateral, even minor downgrades tend to quickly make an impression on their bucket for CCC-rated assets.

LACK OF TRANSPARENCY

The rating agencies’ communications around their ratings actions are confounding. This riddle is no easier to disentangle when visiting the rating agencies’ remarks. They provide only limited clarity about the specifics of how (if at all) they are considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in their rating actions.

When downgrading CLOs, Moody’s mentions that its “analysis has considered the effect of the coronavirus outbreak on the US economy as well as the effects that the announced government measures, put in place to contain the virus, will have on the performance of corporate assets” (Deshpande, Mogunov, and Chatterjee, 2020). But there are no specifics: Moody’s does not explain how. In what ways is Moody’s changing its approach to reflect the analysis it purports to be making? Did the prepayment rate assumptions change? Did the default rate assumptions change? Did the correlation assumptions change? Did the recovery rate assumptions change? Given that Moody’s identifies a largely quantitative methodology article (Kim, et al. 2019) as the “principal methodology” used in the downgrades, it is odd that Moody’s did not express its approach in any way that enables users of ratings to apply the purported considerations within a quantitative framework.

S&P is similarly opaque. When rating new deals and reviewing existing deals, S&P sometimes mentions the pandemic and sometimes does not. For example, in April, S&P never mentioned the effect of COVID-19 on its rating of Deerpath Capital CLO 2020-1 (Kalinauskas, et al. 2020). Moreover, when S&P does discuss the impact of the pandemic, it does so in a nebulous way, which leaves the reader guessing about the particulars of how the rating agency accounts for the pandemic when assigning ratings. When S&P assigned new ratings in May 2020 to notes issued by Guggenheim CLO 2020-1 Ltd, its sole mention of the pandemic was the following boilerplate language:

S&P Global Ratings acknowledges a high degree of uncertainty about the rate of spread and peak of the coronavirus outbreak. Some government authorities estimate the pandemic will peak about midyear, and we are using this assumption in assessing the economic and credit implications. We believe the measures adopted to contain COVID-19 have pushed the global economy into recession (see our macroeconomic and credit updates here: https://ift.tt/2xgUv6g). As the situation evolves, we will update our assumptions and estimates accordingly. (Kalinauskas and Davis 2020).

DEPARTURES AND DEVIATIONS FROM METHODOLOGIES, AND INCONSISTENT APPLICATIONS

Beyond the disappointing lack of transparency, another challenge for investors is that rating agencies appear to be deviating from their published methodologies for assigning and maintaining ratings. Moreover, they deviate in inconsistent ways from one deal to the next.

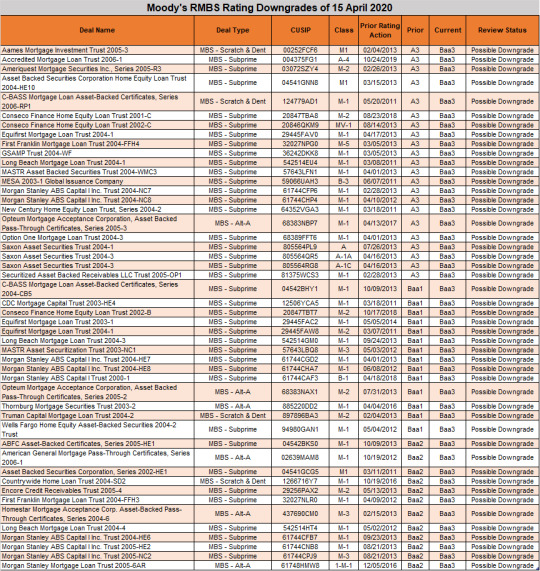

Example 1. In one telling example (Jiang and Vasudevan 2020), Moody’s downgraded 48 MBS on April 15, 2020. The rating agency identified a mostly-quantitative methodology as the “principle methodology” for the rating actions (Vasudevan, Hannoun-Costa, and Muni 2019). Of note, the principle methodology predates the start of the pandemic.

What was particularly striking about the April 15 rating actions was that Moody’s downgraded all of 48 MBS to the same rating level (Baa3) even though they previously carried ratings at a variety of levels (A3, Baa1 and Baa2). Moody’s did not describe a concrete basis for the Baa3 outcome. Although it explained the need for taking action, it provided no details about why Baa3 was the right rating level for the 48 tranches. The rating agency stated: “Our analysis has considered the increased uncertainty relating to the effect of the coronavirus outbreak on the US economy.” But later in the press release it revealed that it “did not use any models, or loss or cash flow analysis, in its analysis” and that it “did not use any stress scenario simulations in its analysis” (Jiang and Vasudevan 2020). It is difficult to reconcile that statement with others to the effect that 1) a quantitative methodology was used and 2) the analysis considered the increased uncertainty relating to the onset of the pandemic.

In June, Moody’s took action on 415 US MBS, confirming its ratings on 35 of them, while downgrading the other 380 (Rossetti and Vasudevan 2020). The announcement, however, contained no language about Moody’s departing from the application of any models. Instead, the boilerplate verbiage in the announcement stated:

Moody’s estimates expected collateral losses or cash flows using a quantitative tool that takes into account credit enhancement, loss allocation and other structural features, to derive the expected loss for each rated instrument. Moody’s quantitative analysis entails an evaluation of scenarios that stress factors contributing to sensitivity of ratings and take into account the likelihood of severe collateral losses or impaired cash flows. Moody’s weights the impact on the rated instruments based on its assumptions of the likelihood of the events in such scenarios occurring (Rossetti and Vasudevan 2020, emphasis added).

Most interestingly, 47 of the 48 MBS, which had been downgraded to Baa3 in April (without the use of a model), were addressed again in June (Rossetti and Vasudevan 2020), this time ostensibly using a quantitative tool. The results were that the securities received different ratings:

10 MBS maintained their Baa3 ratings upon review with a model.

15 were downgraded to Ba2 (i.e., a further two notch downgrade).

22 were downgraded to B1 (i.e., a further four notch downgrade).

Example 2. In recent surveillance updates on CLO ratings, Fitch appears to be applying new scenarios that are not included in its official methodology. For example, in the updates for Jubilee CLO 2014-XII and Penta CLO 5, the agency explained:

Coronavirus Baseline Scenario Impact: Fitch carried out a sensitivity analysis on the current portfolio to envisage the coronavirus baseline scenario. The agency notched down the ratings for all assets with corporate issuers on Negative Outlook regardless of sector.

∗ ∗ ∗

In addition to the base scenario, Fitch has defined a downside scenario for the coronavirus crisis, whereby all ratings in the ‘B’ category would be downgraded by one notch and recoveries would be lowered by 15% (Kelmer and Brewer 2020a; Segato and Brewer 2020a).

More pointedly, Fitch has been regularly deviating from its model-implied ratings (MIRs) in downgrading CLOs notes. In addition, the deviations have not been consistent.

For example, in reviewing certain European CLOs, Fitch refrained from downgrading tranches for which the MIR indicated a one-notch drop. Where the MIR indicated a two-notch drop, the rating agency either refrained from downgrading[1], or did so by just one notch[2]. In some cases, Fitch explained that the deviations were because the MIR results had been “driven by the back-loaded default timing scenario only” (Choraria and Brewer 2020; Ishidoya and Brewer 2020; Segato and Brewer 2020a, 2020b). In other cases, Fitch asserted that it had deviated from the MIRs because the results did not comport with its view of credit quality and also because the MIRs had been “driven by the rising interest rate scenario only, which is not our immediate expectation” (Kelmer and Brewer 2020a, 2020b).

Fitch made several similar out-of-model adjustments when reviewing the ratings across seven CLOs in late July (Torres and Pak 2020). The rating agency stated:

The class C notes in PSLF 2018-4, Ltd., class B notes in PSLF 2019-4, Ltd., and class B notes in PSLF 2020-1, Ltd. experienced shortfalls in some scenarios and the model-implied ratings (MIRs) of these notes were one notch below their current rating levels. However, Fitch considered the magnitude of these failures as minor and isolated to the back-loaded default timing and rising interest rate scenario that was given less weight in the analysis.

∗ ∗ ∗

In addition, MIRs of the following classes were at least one notch higher than their current ratings based on current portfolio analyses, but were not upgraded in light of the ongoing economic disruption … (Torres and Pak 2020).

In contrast to its surveillance practices, Fitch generally makes no mention of ignoring its model-based outcomes in rating new US CLOs. However, in some cases, Fitch has indicated that it is applying stress scenarios in a way similar (but not identical) to surveillance stress scenarios.

For example, when providing ratings to two newly-issued CLO in July 2020, the rating agency explained:

Fitch has applied two additional stress scenarios to the indicative portfolio that envisage negative rating migration as a result of business disruptions from the coronavirus. The first scenario applies a one-notch downgrade (with a CCC-floor) for all assets in the indicative portfolio with a Negative Rating Outlook.… The second scenario assumes a 5% increase in the indicative portfolio’s PCM rating default rates (RDR) for all rating levels.

∗ ∗ ∗

Fitch added a sensitivity analysis that contemplates a more severe and prolonged economic stress caused by a re-emergence of infections in the major economies, before a halting recovery begins in 2Q21. (See Weiss, Joswiak, and Hughes 2020; Hunter, Lycos, and Hughes 2020, with emphasis added).

The second stress scenario used in rating new deals is entirely absent when performing surveillance. It is unclear whether the downside scenarios are being applied equally, as Fitch has left the specifics undefined.

It is somewhat surprising that Fitch would choose to make manual, ad-hoc, overrides to its model-driven outputs in every pandemic-era CLO surveillance action we found because it could not rely on the results produced using its official methodology. Under such a scenario, it would be easier to understand a basic adjustment to the methodology (and the associated model), so that it provides a reliable result that reflects Fitch’s actual views.

WHY IT ALL MATTERS

Investors and other market participants use credit ratings as signals or indicators of creditworthiness that figure, inter alia, into their processes for valuing securities and allocating capital. Securities can also be interrelated. The ratings awarded to some securities also, as we note above, directly impact the performance of other securities that reference or support them. In order for credit ratings to be useful, they must embody a measure of reliability. One of the key aspects of that reliability is that ratings are produced through a consistent, replicable process: the application of a rating agency’s official methodologies.

The ideas of applying official methodologies to produce ratings and doing so in a consistent manner are prominent features of each rating agency’s code of conduct (Moody’s Investors Service 2020, § 1.3; S&P Global Ratings 2018, § 1.2; Fitch Ratings 2017, § 2.1.3). At least one court has held that statements in a rating agency’s code of conduct constitute “specific assertions of current and ongoing policies” and cannot be dismissed as mere puffery upon which investors cannot reasonably rely, United States v. McGraw Hill (2013). Today, applying official methodologies to produce ratings is explicitly required under US [3] and European [4] law .

Likewise, the rating agencies undertake, in their codes of conduct, to provide clear explanations of the rationale behind each rating action (Moody’s Investors Service 2020, § 3.6(b), (c); S&P Global Ratings 2018, § 4.1; Fitch Ratings 2017, § 4.1.3). That is also required under US [5] and European [6] law.

There are compelling reasons for why rating agencies are required to produce ratings by applying their official methodologies. One reason is that it decreases the potential for an individual analyst or team of analysts to abandon criteria in an effort to win new deals by providing advantageous ratings. Rating agencies might argue that they must have some flexibility to stray from their methodologies. To the extent that such a position is valid (and does not violate a rating agency’s legal obligations), we believe that when a rating agency deviates from its official methodology, it has an obligation to explain the rationale for the deviation and to explain in detail how it arrived at the rating produced with the deviation. Moreover, when deviations become the norm, or when they are inconsistent or poorly articulated, we believe that the rating agencies have gone too far. At times, as shown herein, rating agencies have deviated from their methodologies, but failed to explain the analyses that ensued and how they determined the final ratings that they assigned.

CONCLUSION

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the credit rating agencies experienced criticism, private litigation, and government enforcement actions. Enforcement actions in the US were taxing, culminating in f ines of $1.375 billion for S&P and $864 million for Moody’s (US Department of Justice 2015, 2017). The enforcement actions particularly noted that the rating agencies had violated their codes of conduct, which required them to provide objective, independent ratings.

Although the regulatory environment has gotten tougher since the Dodd-Frank Act was signed into law, we remain concerned that rating agencies continue to deviate from their published methodologies whenever it suits them. Based on recent evidence, they appear to view the directive to determine ratings pursuant to their official methodologies and to apply methodologies in a consistent manner as mere suggestions, rather than as mandatory rules.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Adagio VII, classes E and F (Segato and Brewer 2020b); St Paul CLO 5, class F-R (Kelmer and Brewer 2020b); St Paul CLO 6, class E-R (Kelmer and Brewer 2020b); Jubilee 2014-XII, class F-R (Kelmer and Brewer 2020a); Jubilee 2016-XVII, class F-R (Kelmer and Brewer 2020a); Penta 5, class F (Segato and Brewer 2020a).

[2] Euro Galaxy III, class E (Choraria and Brewer 2020); Toro European 4, class E (Ishidoya and Brewer 2020).

[3] 15 U.S.C. § 78o-7(r) (2018), https://ift.tt/34RGDCm; 17 C.F.R. § 17g-8(a)(3)(i), (d) (2019), https://ift.tt/3jxtdPU.

[4] Regulation (EU) No 462/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2013 amending Regulation (EC) No 1060/2009 on Credit Rating Agencies, Art. 1, § 10(a) & Annex II, ¶ 1(h), 2013 O.J. (L146/1) at 16, 31 (May 31, 2013), https://ift.tt/2YO1faD; Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) No 447/2012 of 21 March 2012 Supplementing Regulation (EC) No 1060/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Credit Rating Agencies by Laying Down Regulatory Technical Standards for the Assessment of Compliance of Credit Rating Methodologies, Art. 5, § 1, 2012 O.J. (L140/14) at 15 (May 30, 2012), https://ift.tt/32FgJiE; Regulation (EC) No 1060/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 September 2009 on Credit Rating Agencies, Art. 8, § 2, 2009 O.J. (L302/1) at 13 (November 17, 2009), https://ift.tt/32KihYu.

[5] 15 U.S.C. § 78o-7(s) (2018), https://ift.tt/34RGDCm; 17 C.F.R. § 17g-7(a)(1)(ii)(B), (C) (2019), https://ift.tt/3lD3lEn.

[6] Regulation (EU) No 462/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2013 amending Regulation (EC) No 1060/2009 on Credit Rating Agencies, Annex II, § 4(f), 2013 O.J. (L146/1) at 27 (May 31, 2013), https://ift.tt/32Fo1mt; Regulation (EC) No 1060/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 September 2009 on Credit Rating Agencies, Annex II, Section D, ¶ 5, 2009 O.J. (L302/1) at 28 (November 17, 2009), https://ift.tt/32KihYu.

REFERENCES

Aeron, N., and D. Ham. 2020. “Moody’s Downgrades Ratings on $72 Million of CLO Notes Issued by Nassau 2017-II Ltd.; Actions Conclude Review.” Moody’s press release. July 1.

https://ift.tt/2EJIWwv 427681.

Choraria, P., and A. Brewer. 2020. “Fitch Downgrades One Tranche of Euro Galaxy III CLO B.V., Maintains RWN on One and Affirms the Rest.” Fitch press release. May 7.

https://ift.tt/2YTTaRX.

Deshpande, A., L. Mogunov, and D. Chatterjee. 2020. “Moody’s Places Ratings on 241 Securities From 115 US CLOs on Review for Possible Downgrade; Also Places Ratings on 2 Linked Securities on Review for Possible Downgrade.” Moody’s press release. June 3.

https://ift.tt/31JJPhf.

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Pub. Law No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376 (2010)

https://ift.tt/2EC9f86.

Fitch Ratings. 2017. “Code of Conduct and Ethics.” July.

https://ift.tt/3beB7uT.

Hu, D., S. Anderberg, R. E. Schulz, S. Wilkinson, and R. Muthukrishnan. 2020. “CLO Insights: 63 CLO Tranches Downgraded by 1.2 Notches on Average in July.” S&P newsletter. July 31.

Hunter, M., K. Lycos, and A. Hughes. 2020. “Fitch Rates Ballyrock CLO 2020-1 Ltd.” Fitch press release. July 8. https://ift.tt/3juJlSo.

Ishidoya, K. and A. Brewer. 2020. “Fitch Downgrades One Tranche of Toro European CLO 4 DAC and Affirms Rest; Two Tranches on RWN.” Fitch press release. May 18.

https://ift.tt/3jqlxPs.

Jiang, Z., and S. Vasudevan. 2020. “Moody’s Places 404 Classes of Legacy US RMBS on Review for Downgrade.” Moody’s press release. April 15.

https://ift.tt/2QF421o.

Kalinauskas, P., and C. Davis. 2020. “Guggenheim CLO 2020-1 Ltd. Notes Assigned Ratings.” S&P press release. May 4.

https://ift.tt/32DiX1Q.

Kalinauskas, P., T. Walsh, W. Sweatt, and D. Haynes. 2020. “Deerpath Capital CLO 2020-1 Ltd. Notes Assigned Ratings.” S&P press release. April 7.

https://ift.tt/34R66M4.

Kelmer, S., and A. Brewer. 2020a. “Fitch Assigns Negative Outlook to 1 Tranche and Downgrades Another of Jubilee CLO 2014-XII B.V.” Fitch press release. July 3.

https://ift.tt/3jtKOby.

——. 2020b. “Fitch Downgrades 2 St Paul’s CLOs with 3 Tranches of Each CLO on RWN or Negative Outlook.” Fitch press release. June 29.

https://ift.tt/3jrFgOE.

Kim, J., R.O. Torres, I. Perrin, T. Klotz, A. Remeza, and J. Hu. 2019. “Moody’s Global Approach to Rating Collateralized Loan Obligations.” Moody’s methodology report. March 8.

https://ift.tt/3jxYy5i.

Moody’s Investors Service. n.d. “Non-Financial Corporates: Rating Activity During COVID-19.” Moody’s infographic.

https://ift.tt/2QDYd4z.

Moody’s Investors Service. 2020. “Code of Professional Conduct.” March.

https://ift.tt/3hRPiIQ

Rossetti, N., and S. Vasudevan. 2020. “Moody’s Takes Action on 415 US RMBS Bonds from 237 Deals Issued Prior to 2009.” Moody’s press release. June 9.

https://ift.tt/31IE6s4.

Ryan, S., and E. Tamburrano. 2020. “How COVID-19 Changed the European CLO Market in 60 Days.” S&P comment. May 6.

https://ift.tt/2ESLDvo.

Segato, G., and A. Brewer. 2020a. “Fitch Ratings Revises One Tranche of Penta CLO 5 DAC to Negative Outlook; Affirms Ratings.” Fitch press release. July 6.

https://ift.tt/3luoRee.

——. 2020b. “Fitch Revises One Tranche of Adagio VII CLO DAC to Negative Outlook; Affirms Ratings.” Fitch press release. June 26.

https://ift.tt/3537ziP.

Serino, N., S. Kesh, and S. Pranshu. 2020. “Default, Transition, and Recovery: Consumer and Service Sector Defaults Help Push The 2020 Corporate Tally To 147,” S&P comment. July 31. https://ift.tt/2YNqWZ2.

S&P Global Ratings. 2018. “S&P Global Ratings Code of Conduct.” March 1.

https://ift.tt/2EUshpH.

Torres, C., and A. Pak. 2020. “Fitch Affirms 38 Tranches from Seven Static CLOs; Removes Rating Watch Negative,” Fitch rating action commentary. July 29.

https://ift.tt/3ghWDRa.

US Department of Justice. 2015. “Justice Department and State Partners Secure $1.375 Billion Settlement with S&P for Defrauding Investors in the Lead Up to the Financial Crisis.” Press release. February 3.

https://ift.tt/2eu2nbJ.

US Department of Justice. 2017. “Justice Department and State Partners Secure Nearly $864 Million Settlement with Moody’s Arising From Conduct in the Lead up to the Financial Crisis.” Press release. January 13. https://ift.tt/2jhuizp.

US v. McGraw Hill, No. CV-13-0779 (C.D.Ca., July 16, 2013) (order denying defendants’ motion to dismiss). https://ift.tt/3jtKHNa.

Vasudevan, S., O. Hannoun-Costa, and K. Muni. 2019. “US RMBS Surveillance Methodology.” Moody’s rating methodology. February 22.

https://ift.tt/31JJPxL.

Weiss, C., A. Joswiak, and A. Hughes. 2020. “Fitch Rates HalseyPoint CLO II, Ltd.” Fitch press release. July 1.

https://ift.tt/3lL98Yy.

----------

Gene Phillips is the CEO of PF2 Securities Evaluations, Inc. in Los Angeles, CA. [email protected]

Mark Adelson is the editor of The Journal of Structured Finance, in New York, NY. [email protected]

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2G66GeD

0 notes

Text

Fraud as a Pathogen of Humanity

by Joe Pimbley, who consults for PF2, and director Gene Phillips

The sudden crash of Wirecard dominates headlines. Though pernicious, the fraudulent activity of this eminent European company is quite common. Fraud is everywhere and we must guard against it just as our bodies resist harmful disease.

Fraud at Wirecard

Wirecard, the large German payment processor and DAX 30 constituent, filed insolvency proceedings in late June 2020.[i] The firm had long faced contested allegations of false or questionable bookings of revenue and profits with pressure increasing in January 2019.[ii] In a final blow, Wirecard’s audit firm could not verify the existence of stated balance sheet cash of EUR 1.9 billion.[iii] An apt description of Wirecard’s subsequent corporate fate is Lemony Snicket’s “death swooped down like a bat.”[iv]

Fraud is everywhere

Fraudulent statements and behavior of human beings are as old as humanity itself and will continue until the death of our species. This sentiment is not a denunciation of people; it is merely a characterization of human society. As the joke of our current era goes: human guile is not a bug; it’s a feature.

Our definition of “fraud” casts a wide net to include one extreme of telling blatant lies, for example, to sell the Brooklyn Bridge to tourists, while also capturing the other extreme of deliberately failing to correct a false impression that others may have of you. (We know of a Physics Nobel laureate who, in answer to a direct question, told the U.S.-based interviewer for his first professional job that his college grade-point-average was 4.0. The interviewer was visibly impressed. Surprised by this reaction and realizing the interviewer’s likely error, the future laureate did not qualify the information by stating that 4.0 was a terrible GPA in his home country of Norway.)

The Brooklyn Bridge story is the classic fraud example. Most of us would consider the interviewer’s ignorance of the Norwegian GPA scale not to be an act of fraud on the part of the young job applicant. Of course, there is a vast middle ground between these extremes. We see all sections of this middle ground in our personal and professional lives. Here are a few “middle ground” examples of varying import one of the authors witnessed directly with past employers or learned confidentially from colleagues:

On a derivative trading floor, managers assigned trade identification numbers in a manner that would give counterparties the impression that the trading floor executed ten times more trades than the actual number.

A risk manager discovered an error in a capital adequacy calculation agreed a decade earlier with the firm’s dominant regulator; the General Counsel chose not to inform the regulator because "it would be confusing.”

A senior executive of a credit rating agency told a rating analyst what the final rating should be for the debt of a new client (i.e., “just prepare an analysis that reaches the rating we want”).

Following the ouster of a CEO during a year of painful losses, the new CEO entered and asked the internal accountants to find and take as many additional losses as possible for that current year.

So fraud, in the sense of giving deceptive information or withholding information for the purpose of helping an individual, group, or company, is everywhere. These four examples are somewhat trivial and one might consider only one or two, or perhaps none, of them to be “true fraud.”

The Ponzi scheme template for fraud

Broadly, the fraud allegations against Wirecard are for misstatements of financial condition and activity. Instead of delving into the Wirecard details, we discuss a simpler, generic variant of such fraud that the financial industry calls “the Ponzi scheme.”[v]

In a Ponzi scheme, an investment manager solicits funds from investors to make specified purchases of assets (for example, real estate, stocks, bonds, small businesses, et cetera). Either through losses on these assets or embezzlement of the manager or both, the value of total assets falls. This situation becomes a Ponzi scheme when the investment manager deliberately misstates the current asset value in reports to the fund investors. Believing the fund to be healthy and relying on the (false) manager statements, current investors will tend to keep their principal invested and new investors will add money to the fund. The Ponzi fraud may remain undetected as long as investor redemption requests do not exceed the sum of (diminished) assets and inflows of new investor money.

In its mildest form, the perpetrator of a Ponzi fraud does not begin the enterprise with criminal intent. Rather, the manager’s investments perform poorly and, fearing investor withdrawals and business failure as consequences of honest disclosure of this performance, the manager chooses to make false statements. This is the paradigm for Wirecard-like frauds. Management makes false statements and obfuscations to cover poor performance or to gain some undeserved short-term benefit.

Fraud is a pathogen of human society

A pathogen is a virus, bacterium or other agent that produces disease. Pathogens are ubiquitous, both internal and external to our bodies. We have developed practices as well as natural and man-made defenses to counter most pathogens. Humanity would not exist otherwise. Pathogens vary widely in their infection frequency and lethality and generally do not kill their hosts (not immediately, at least).

Fraud is very much a pathogen of society. Its goal is not to kill the host since, without a mostly healthy society, fraud would not be fruitful. Like pathogens, fraud is everywhere and there is no prospect or possibility of eliminating all fraud.

But society has an immune system deriving from learned and innate caution and skepticism. We also have experiences and stories of the personal and business worlds that become lessons for best practices.

Combat fraud as we would a pathogen

There are many strategies for investors to avoid fraud just as there are strategies for people to avoid disease. Our list below blends some time-tested ideas with those that are most relevant to the Wirecard debacle.

Be consciously aware that fraud is possible in any investment. It may seem that significant fraudulent activity is less likely in a widely studied investment such as a Microsoft or Wirecard, but fraud at some level is everywhere.

Think for yourself, ask your own questions. The apparent confidence of many other investors can provide a false sense of comfort.

Realize that many people are inherently dishonest, and certainly “less than honest.” People do lie.

Think critically about “the story” of the investment you’re considering. If it does not make sense to you, don’t invest. Trust yourself more than you trust anyone who tells a story you do not understand or believe.

Three elements of the financial world’s “immune system” to fight fraud are auditors, regulators and credit rating agencies. For any potential investment, determine whether there are relevant auditors, regulators and rating agencies and consult their findings. Illness sometimes prevails because an immune system component fails to fulfil its role.

Auditors make mistakes. Audit firms investigate the financial statements of their clients to certify absence of material misstatements and adherence to accepted accounting policies. Since the client pays the auditors for the service, the auditors have a “moral hazard motive” not to press fraud investigations vigorously. While most audit firms DO have strong motives to protect their brands and reputations by maintaining high standards for their investigations, that is no guarantee that individual audit groups will do their jobs honestly or competently. Hence, do not base a positive investment decision on satisfied auditors.

Regulators are government employees. They and the regulations they supervise and enforce are generally well intended. But corporate entities that are willing to deceive investors will also deceive the regulators. Ironically, regulators will often defend their regulated firms from external accusations because it “looks bad” for the regulators if such accusations are valid. Further, the mission of regulators favors protection of the banking system and government interests over those of investors in individual firms. Hence, do not base a positive investment decision on satisfied regulators.

Credit rating agencies are non-government companies that claim to advocate for investors. They would like you to think of them as “expert investors” that provide unbiased opinions of investment risk. But this profile is inaccurate. The rating agencies do not invest and, therefore, do not take the risk you will take as an investor. Further, their paying clients are the corporate firms themselves, which means that the rating agencies have the same “moral hazard motive” as the auditors. Though the meanings of the credit ratings themselves are poorly defined, we do consider it valuable to have one or more ratings for corporate debt securities you may purchase. For “investment-grade” credit ratings, ~80% of such securities will have reasonably low risk (allowing for the errors that these rating agencies do make). Do not rely only on a credit rating for a positive investment decision on a debt security.

Pay attention to the statements of vocal critics of entities in which you have invested or may invest. Financial journalists, investment advisors and other investors will sometimes publish negative results from their own investigations. Read such opinions skeptically since the reports may be mistaken or deliberately false or exaggerated. Even when wrong or mostly wrong, such third-party views and rebuttals from the investment entity, if any, stimulate your own productive analysis.

------------------------------------

[i] See “Wirecard files for insolvency owing $4 billion,” New York Post

[ii] See B. Jennen and N. Comfort, “Wirecard Whistle-Blower Tipped German Watchdog in Early 2019,” Bloomberg

[iii] See R. Browne, “It was once Germany’s fintech star. Now, a missing $2 billion puts Wirecard’s future in doubt”

[iv] See L. Snicket, The Miserable Mill, Scholastic, Inc., 2000. The excerpted quote is available at https://ift.tt/3hmlwLu.

[v] See the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission discussion of Ponzi schemes

via Blogger https://ift.tt/3juVYNU

0 notes

Text

TruPS CDOs: What Virus?

While the rating agencies have been actively downgrading bonds across almost all sectors, we thought it may be fun to compare the performance of regional US banks during COVID-19 against their performance during the 2007-2008 financial crisis.

Bank TruPS CDOs are deals supported by trust preferred securities issued by regional/community banks. Interestingly enough, since the onset of the coronavirus, the TruPS CDOs (if anything) have been going up from a ratings perspective.

Yesterday, Kroll Bond Rating Agency affirmed the ratings of a 2018 deal, without making any mention of the coronavirus. Meanwhile in a series of (we count four) ratings releases since March, Fitch has upgraded dozens of tranches, and affirmed many others too. No downgrades, and no mention of COVID-19.

So why the upgrades? The likely answer is that many of the upgrades have been lingering for a few years, and just had to happen at some stage, so why not now?

Here's one of the more interesting bonds, the $70mm top tranche (originally AAA) of a 2005 deal called Regional Diversified Funding 2005-1, which has seen both crises.

Read the chart from the bottom up. Pre-crisis, Fitch has it at AAA, until it was (rather dramatically) downgraded on a single day to CCC in 2009. That's incredible. Okay, fast forward and it's single C in 2010, Fitch's lowest rating: an expectation of full or almost full wipeout.

Since it had gone from AAA (sacrosanct) to C (a dead-beat) it's just as incredible that it has since marched back up to CC (in 2015, of all times) and then CCC, BB and now A (as of yesterday), which is a serious investment grade rating.

Nevermind the coronavirus!

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2yHvGpb

0 notes

Text

Rating Agency Déjà Vu

Short Shrift for Surveillance

There seems to be a scramble on at the rating agencies, but we think we’ve seen this scramble before.

Beginning late in 2006 the subprime and alt-A residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) market began its long downward slide into unimaginable losses.

The credit rating agencies – of which S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch have the leading market shares – appeared to be slow to respond. Perhaps there was good reason in the early months of 2007. Or perhaps not. An argument against promptly downgrading the RMBS was to wait for a few monthly reporting periods to validate the trend of rising mortgage delinquencies. The risk in waiting, of course, is that it suddenly becomes “too late” and you are required to implement larger, more frantic downgrades than in the alternative in which you had been downgrading incrementally if and when appropriate. But while ratings were yet to be downgraded there was no doubt, however, that the values and prospects of both the RMBS and their underlying mortgages were tumbling violently.

We’re reminded of the iconic J.P. Morgan himself who once said (paraphrase): “Every man has two reasons for doing something. There’s the reason he gives that sounds good and then there’s the real reason.”

The rating agencies had at least one “real” reason for not downgrading RMBS bonds promptly: for RMBS and other structured products, they were ill-equipped to provide the services! From our perspectives having been in the industry, reviewing Congressional testimony and materials from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, and having conferred with others playing similar roles at other agencies, we can tell you that the rating agencies did not have the capacity to methodically or efficiently oversee their models and ratings on the RMBS bonds they purported to be monitoring. There was very little that was programmatic to it. The process for the supposedly continuous, ongoing surveillance of thousands of RMBS bonds was (shockingly) manual. Or it was not done at all.

The rating agencies were much more concerned with clipping high revenue-generating new deal rating tickets, and much less concerned about providing the required surveillance on existing deals. Monies for surveillance, after all, get paid whether or not the service is provided.

So the RMBS downgrades came in waves spaced out over many months in 2007. The rating agencies placed many bonds on downgrade watch prior to the requisite modeling and analysis based on mortgage characteristics, transaction vintage, and broad market performance. This “watch period” supposedly bought the rating agencies time to perform the actual analysis before specifying actual downgrades.

Of course, while the existing ratings were intermittently “wrong” or awaiting correction, there was much ado about how to rate new deals or other existing deals that depended on those outstanding – but yet to be addressed – ratings.

Now it’s 2020 and we wonder if the ratings surveillance process has improved at all. The tremendous economic stress of the coronavirus (“COVID-19”) raises doubts of the sudden inability of homeowners to continue making mortgage payments. Many of these debtors are now unemployed with much uncertainty for the future. The house prices themselves may be greatly depressed – we won’t know until the end of this suspension period for real estate transactions. Falling home prices in 2007-2008 themselves prompted many mortgage defaults. Thus, it’s fair to say that RMBS bonds have much greater risk of default than they did at the beginning of the year.

Moody’s acknowledges the impact of the coronavirus, and the substantial uncertainty it brings with it.

“Our analysis has considered the increased uncertainty relating to the effect of the coronavirus outbreak on the US economy as well as the effects of the announced government measures which were put in place to contain the virus. We regard the coronavirus outbreak as a social risk under our ESG framework, given the substantial implications for public health and safety.”[1]

Importantly, Moody’s accepts that “It is a global health shock, which makes it extremely difficult to provide an economic assessment.” However, Moody’s is in the business of making these assessments, meaning it needs a robust and methodical way of tackling the new variable, and accounting for the uncertainty that comes with it.

The rating agencies have two very interesting vocations at present.

First, they’re actively downgrading RMBS (and most other bonds too).

Next, they’re actively rating new deals, even though some of the new deals are backed by assets that they’re simultaneously downgrading. For example, rating agencies rated five new CLO deals, backed by loans in April; meanwhile, as of early April JPMorgan was showing that loan downgrades were outpacing upgrades at a rate of 3.5-to-1.

Part 1: Ratings Downgrades

Moody’s announced, on April 15, its placement of 356 RMBS bonds on review for downgrade and the actual downgrade of 48 bonds to the Baa3 level.[2] The downgraded certificates remain on watch for further downgrade.

Placing bonds on watch for potential downgrade is not, alone, all that interesting. But the downgrades were interesting. Moody’s rationale:

“The rating action reflects the heightened risk of interest loss in light of slowing US economic activity and increased unemployment due to the coronavirus outbreak. In its analysis, Moody's considered the sensitivity of the bonds' ratings to the magnitude of projected interest shortfalls under a baseline and stressed scenarios. In addition, today's downgrade of certain bond ratings to Baa3 (sf) is due to the sensitivity of the ratings to even a single period of missed interest payment […]”

There are a few things that are interesting here.

First, the lack of specificity. Moody’s does not specify any quantitative elements of its analysis – Moody’s does not cite to changes in default rates, severity rates, recovery rates or prepayment speeds – that were adjusted to accommodate COVID-19 or that justify the downgrade action or explain the specific rating as Baa3, which is (curiously) the lowest level of investment-grade. It is all rather vague.

Second, you might have noticed some unusual language there. The “downgrade of … ratings … is due to the sensitivity of the ratings…” That is all meaningless. One does not downgrade a rating because of the sensitivity of the rating. All ratings, aside perhaps from some Aaa ratings, are “sensitive.” One downgrades because of a higher potential for default or loss, as ascertained by an analysis performed – not because of the sensitivity.

That brings us to the next issue: what analysis was performed? The short answer is, well, that there was no proper analysis performed! Aside from Moody’s failure to describe the specific analysis performed, we have at least two reasons to believe that no analysis was performed.

Moody’s does not have a methodology for incorporating the coronavirus stress: Moody’s explicitly acknowledges that the principal methodology used in these ratings was the "US RMBS Surveillance Methodology" published in February 2019, which of course was pre-COVID-19

Moody’s acknowledges that it did no modeling: “Moody's did not use any models, or loss or cash flow analysis, in its analysis. Moody's did not use any stress scenario simulations in its analysis.”

Why does it matter that Moody’s did no modeling? Because the Feb. 2019 methodology referenced is a quantitative one, and it requires extensive modeling. One simply cannot apply a quantitatively-heavy methodology while applying no models. Ergo, we suspect that Moody’s did not apply, or could not have properly applied, the Feb. 2019 methodology.

Altogether, we see 48 bonds downgraded to Baa3, absent:

an updated methodology that reflects the key new coronavirus risk, despite acknowledgment of the key importance of this risk to the deals;

a proper application of the existing methodology from Feb 2019 or any explanation as to the deviations from the methodology; and

the application of any models at all.

It is commendable to tell investors that you have not modeled cash flows, or performed any stress scenario analyses. But the questions are then: What was done and how exactly did you arrive at a Baa3 rating? What is the point of publishing a ratings methodology if you are not going to follow it, or describe specific deviations from it, so that investors can similarly follow your reasoning?

Strictly speaking and adhering to the meaning of Moody’s ratings, it is extraordinarily difficult to imagine how Moody’s could determine that 48 bonds should simultaneously earn the new, lower rating of Baa3 without analysis. With no quantitative estimate for increased loss or diminished and re-directed cash flow, how can Moody’s determine the precise new rating level?

One thought, however, is that Moody’s guessed at the rating based on the methodology, and perhaps because there were no models to apply: in the rush of rating new deals, maybe Moody’s hadn’t gotten around to building well-functioning models to replace the old ones? Or, equally plausible is the possibility that Moody’s models do not exist in the cloud, meaning that the Moody’s analysts and supervisors working from remote (home) locations could not access the necessary models, data or tools to perform their reviews. What an astounding disclosure this would be, if true, for a global data-centric organization!

Whatever the reason, the Baa3 ratings are flawed. No analysis by an outsider, or perhaps even a Moody’s insider, when applying Moody’s methodology, can credibly achieve an outcome of Baa3. It is just a guess.

Part 2: New Ratings

The rating agencies are actively downgrading bonds, loans, and credit instruments across most sectors and industries.[3] Many of these downgrades may be well-intended, due to newly introduced COVID-19-related risks. But while they are downgrading these (newly unstable) credits they are rating new structured finance credits that are supported by these very same unstable credits. Their structured finance ratings problematically look to their own ratings of the credits, which are being downgraded daily. Thus, new ratings cannot be said to be robust to the degree the rating agencies lack confidence in the sturdiness of their own underlying ratings. Moreover, the new structures are not being rated according to any new, post-coronavirus methodology. So we might expect those newly-created bonds to be similarly downgraded, too, in short order.

When S&P rated Harriman Park CLO, a new deal, on April 20th, S&P said nothing at all about coronavirus in its press release. In explaining how it came about its ratings, S&P cited only to related criteria and research from 2019 and earlier. There is no evidence that any scenario was run at all differently by S&P. No mention is made of any newly-imposed stress scenario being run.

When Fitch rated this same deal, Fitch explained its thought process and how it is deviating from its pre-existing methodologies. That’s a whole lot better than S&P in this case, but even Fitch failed to explain the “why.” Fitch simply explained what it is doing, but not why what is doing makes sense. How have they calibrated their models (if at all)? How do we know the new assumptions are adequate or comprehensive?

“Coronavirus Causing Economic Shock: Fitch has made assumptions about the spread of the coronavirus and the economic impact of related containment measures. As a base-case scenario, Fitch assumes a global recession in 1H20 driven by sharp economic contractions in major economies with a rapid spike in unemployment, followed by a recovery that begins in 3Q20 as the health crisis subsidies. As a downside (sensitivity) scenario provided in the Rating Sensitivities section, Fitch considers a more severe and prolonged period of stress with a halting recovery beginning in 2Q21.

Fitch has identified the following sectors that are most exposed to negative performance as a result of business disruptions from the coronavirus: aerospace and defense; automobiles; energy, oil and gas; gaming and leisure and entertainment; lodging and restaurants; metals and mining; retail; and transportation and distribution. The total portfolio exposure to these sectors is 9.9%. Fitch applied a common base scenario to the indicative portfolio that envisages negative rating migration by one notch (with a 'CCC-' floor), along with a 0.85 multiplier to recovery rates for all assets in these sectors. Outside these sectors, Fitch also applied a one notch downgrade for all assets with a negative outlook (with a 'CCC-' floor). Under this stress, the class A notes can withstand default rates of up to 61.8%, relative to a PCM hurdle rate of 53.9% and assuming recoveries of 40.6%.”

While it continues to rate new deals, S&P (for example) has placed roughly 9% of all its CLO ratings on watch negative since March 20th.[4]

The rating agencies suffered tremendous reputational damage when they were found to be rating new CDO deals in 2007 while they already knew they could no longer rely on the RMBS ratings supporting those deals, as they would imminently be downgraded. Once the CDO rating analysts knew the RMBS ratings were unstable and about to be downgraded, the CDO analysts were taking a legal risk in producing ratings they knew would not be robust. It can be difficult to turn away the sizable revenues that come with rating new deals – even when you do not have a sustainable ratings methodology or any conviction in the credibility of the data (including ratings) you are relying on.

The essence of formulating credit ratings for all entities (structured, corporate, municipal, etc.) requires the ability to estimate future revenues, expenses, and liabilities for a multi-year time period. Such estimates are critical to the rating process. As we write, forecasting for the broad economy and for most specific entities is highly uncertain. We do not see how it is possible to perform meaningful rating analysis amidst this uncertainty. Hence, the credit rating agencies should arguably pause all new ratings until uncertainty declines or until they develop rating methodologies that fully incorporate the wide uncertainty.

Part 3: Summary/Conclusions

Stale ratings, inflated ratings and other faulty ratings can sometimes go unnoticed during an upswing. But shortcomings become most pronounced during an economic downturn or crisis. We are concerned that we are (again) seeing the result of years of prior, weak, ratings mismanagement.

When crises occur, rating agencies should be able to swiftly update their methodologies, models and ratings. And rating agencies should stave off rating new deals until and unless they have strong and current methodologies in place to explain their new ratings and how their ratings accommodate the upheaval, whatever it may be.

Rating agencies seem quickly to have forgotten (or simply to have ignored) the lessons they should have learned from the last crisis. Regulatory settlements with the DOJ for subprime crisis-era misconduct (S&P for $1.375 billion[5], and Moody’s, in the amount of $864 million[6]) concerned issues in which they deviated from their code, which required them to provide objective, independent ratings. Those were not about the rating agencies being wrong, or failing to predict the downturn, but closer to argument that the rating agencies failed to believe their own ratings.[7]

In the above case, we would have to ask how Moody’s can be sure that Baa3 is the right rating – for all 48 bonds, across different deals, structure types and vintages – consistent with its methodology, given it failed to apply any modeling?

This article was co-written by Joe Pimbley, who consults for PF2.

https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-places-404-classes-of-legacy-US-RMBS-on-review--PR_422633

https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-places-404-classes-of-legacy-US-RMBS-on-review--PR_422633

https://ift.tt/2WH2W9I

https://www.opalesque.com/industry-updates/5969/96-reinvesting-clo-ratings-placed-on-creditwatch.html

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-and-state-partners-secure-1375-billion-settlement-sp-defrauding-investors

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-and-state-partners-secure-nearly-864-million-settlement-moody-s-arising

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-02-05/s-p-won-t-employ-first-amendment-defense-in-u-s-ratings-lawsuit

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2SgqShc

0 notes

Text

Wrong Zoom ReZooms Trading - An Inefficient Market

The right Zoom is taking off. But, the wrong Zoom has really taken off!

ZOOM is the equity ticker of wrong Zoom, a Chinese company called Zoom Technologies that has done nothing remarkable this year. But at one point, wrong Zoom's stock was up 1890% since year-end 2019.

Meanwhile right Zoom, Zoom Video Communications, is based in California. It stock trades under the ticker ZM and has enjoyed some nice gains too (max of 135% up since year-end).

On March 25, 2020, the SEC suspended trading in wrong Zoom:

“It appears to the Securities and Exchange Commission that the public interest and the protection of investors require a suspension of trading in the securities of Zoom Technologies, Inc. (“ZOOM”) (CIK# 0000822708) because of concerns about the adequacy and accuracy of publicly available information concerning ZOOM, including its financial condition and its operations, if any, in light of the absence of any public disclosure by the company since 2015; and concerns about investors confusing this issuer with a similarly-named NASDAQ-listed issuer, providing communications services, which has seen a rise in share price during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.”)

Notes on wrong Zoom: Zoom Technologies Inc., headquartered in Beijing, has zero reported revenue since 2011. It was delisted from NASDAQ in October 2014. The stock trades OTC in the US, specifically in the “Grey Market,” and dealers may only quote the stock on behalf of an unsolicited customer order.

Since April 18, 2019 OTC Markets has designated the stock “Caveat Emptor” (along with a skull and cross-bones marker), to highlight to market participants that Zoom Technologies Inc. (ticker: ZOOM) is not related to Zoom Video Communications, Inc. (ticker: ZM). [1] Caveat Emptor is a designation that OTC Markets reserves for the sketchiest of penny stocks.

On March 25, 2020, the SEC suspended trading in ZOOM. Wrong Zoom's stock resumed trading April 14, 2020 under the ticker ZTNO.

We are not aware of anyone making the case that the market for grey market OTC stocks with “Caveat Emptor” designations is an efficient market; but still, who were/are these purchasers of ZOOM? Did many actually confuse wrong Zoom with right Zoom, or was it predominantly speculative traders betting that other folks would confuse the two stocks, under a “greater fool” theory?

[1] https://www.otcmarkets.com/stock/ZTNO/news/OTC-Markets-Designates-Zoom-Technologies-Inc-with-Caveat-Emptor?id=225417

via Blogger https://ift.tt/3exgTNW

0 notes

Text

Investor Protections (of a Legal Variety) in the Aftermath of a Meltdown

In a recent journal article available here, mortgage guru Mark Adelson has compiled another of his terrific analyses of the mortgage meltdown, and some of the letdowns of post-crisis legislation.

You have to read the piece in its entirety, but here are just some of his analytical gems and opinions to give you a flavor for what’s inside:

“The mortgage meltdown produced $1 trillion (±20%) of losses from 2007 through 2016. The losses were borne primarily by investors in non-agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS).”

“Investors around the world invest in the US markets because they have integrity and there are multiple checks in place to ensure that misrepresentations are remedied.”

“Nonetheless, the Mortgage Meltdown of the late 2000s left many investors reeling. They suffered huge losses on non-agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) issued from roughly 2005 through 2007. Those losses came from a wave of defaults and foreclosures on mortgage loans originated during those years. During that time, there was a broad deterioration of practices across the mortgage lending and securitization industry.”

“The full extent of the breakdown in practices started to come to light in 2013, when the US Department of Justice (DOJ) began settling lawsuits against the major banks.”

“Common types of defects included (i) defective appraisals that overstated the value of homes, (ii) exceptions allowed without sufficient compensating factors, (iii) missing or inaccurate documentation of borrower income or assets, and (iv) misstated occupancy status. When the loans were included in MBS deals, the offering materials did not disclose the defects.”

“By the time this mounting evidence came to light, it was too late for most investors to sue under the federal securities laws to recover their losses.”

“The legislative response to the mortgage meltdown and the broader financial crisis did not address the time limits issue. The time limit under the 1933 Act remains a critical piece of unfinished business. If it is not addressed, America’s capital markets will remain vulnerable to a repeat of the mortgage meltdown experience. We propose extending the 1933 Act’s maximum time limit to 12 years for actions based on misstatements or omissions in connection with the sale of non-agency MBS (i.e., actions under 1933 Act §§ 11 and 12(a)(2)).”

“Issuance of non-agency MBS fell off sharply following the mortgage meltdown. […] Attempts to revive the non-agency MBS market have been unsuccessful.”

“The aftermath of the mortgage meltdown offers potential lessons for lawyers, business professionals, and policy makers. The episode was arguably the largest failure of legal protections for investors since the Great Depression. Investors have recovered only a small percentage of their total losses.”

That’s just a taste – for more, download the paper by clicking here.

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2IRQ4pm

0 notes

Text

Leveraged Loan CLOs and Rating Agencies - Policy Solutions

Over the last couple of years, financial market commentators have become concerned that leveraged loans and Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) are becoming the newest “financial weapons of mass destruction”. The fear is that mispricing and over-production of these assets could lead to a bubble that would ultimately take down our financial system – just as subprime mortgage backed securities did a dozen year ago.

Further, critics worry that rating agencies – still following the traditional issuer-pays model – lack the incentive to protect us from a leveraged lending meltdown. Instead, agencies are thought to be engaged in a "race-to-the-bottom," lowering their rating standards to enable (or keep) even the less credible corporate borrowers in the Investment Grade category.

There are many viable solutions to the problems that face the rating agencies, or the marketplace that relies on them. Here are two.

If SEC-licensed Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organizations (NRSROs) – or so-called credit rating agencies -- are not up to the task, investors could turn to non-licensed analytics firms to more objectively evaluate leveraged loans and the securitization vehicles that house them. Outside of the market for debt and credit-based financial products, we see many types of ratings published by non-licensed providers. For example, Consumer Reports assigns ratings to a wide array of products, US News ranks colleges and Yelp assigns ratings to service establishments. These systems are imperfect and sometimes deservedly attract criticism, but no rating system is perfect and the widespread use of these assessments suggests that users find them valuable.

The main barrier to entry for non-NRSROs that would want to assess leveraged loans and CLOs specifically is lack of access to data, and this is an issue that the SEC could rectify. The leveraged loans at the center of CLOs are often borrowings made by privately held companies – including holdings of private equity firms – that are not required to make their financial statements public. Only current investors and the rating agencies hired to rate these entities can see these financial statements.

The SEC could simply require all such companies that borrow on the leveraged loan market, subject to a minimum borrowing size, to file their 10-Q and 10-K statements on the EDGAR system. That way independent firms could assess their financial status and estimate default probabilities and expected losses on their loan facilities.

Second, CLO issuers should be required to post both their loan portfolios and details of their capital structures on EDGAR as well. In such a scenario, CLOs could no longer be exempted under Section 4(a)(2) of the Securities Act and sold as Rule 144A private securities. Instead, they would be regulated as public securities.

Finally, many CLOs have complex rules governing how proceeds from the collateral pool should be distributed among the various classes of noteholders and the firms – like the asset manager – that provides services to the CLO deal. These “priority of payment” provisions are outlined in dense legalese included in the CLO's offering documents. Rather than compelling investors and analysts to decipher these legal provisions, issuers should be required to code them as computer algorithms which would also be published as part of the deal’s disclosure. CLOs could then operate like any other “smart contract,” easing the work of deal participants and third parties who need to analyze the many “what-ifs” that can occur over the life of a transaction.

Leveraged loans and CLOs may or may not be the ticking time bomb that will blow up our economy. One way to limit the potential for bubble-creation is to remove dependence on parties (like the incumbent credit rating agencies) that are financially motivated to provide high ratings, thus prompting issuers and other market participants to seek out their services. Thus, our solution is, in short, to make these transactions more transparent, so that other third parties can access information on the securities and analyze them in a cost-effective manner.

via Blogger https://ift.tt/3897ysg

0 notes

Text

Mall Shooting Highlights Folly of Single Asset CMBS Ratings

On Black Friday, the Destiny USA Shopping Mall in Syracuse, New York was evacuated after a shooting in the food court. The following day, a knife fight broke out in the mall’s entertainment complex, adding to shoppers’ apprehension about visiting. This apprehension should be shared by holders of Commercial Mortgage Backed Securities (CMBS) collateralized solely by Destiny USA loans, including owners of $215 million in AAA-rated senior notes. While one short-lived catastrophic event will not lead directly to bond defaults, the outbreaks of violence at an already troubled mega-mall cast a harsh light on rating agency decisions to assign their highest grades to structured notes wholly lacking the protection afforded by diversification.

As Marc reported previously, rating agencies have repeatedly assigned top ratings to CMBS secured by mortgages on only a single shopping mall. These shopping mall deals are a subcategory of so-called Single Asset / Single Borrower (SASB) CMBS. Buyers of AAA-rated SASB securities are protected from adverse performance only by overcollateralization – the fact that subordinated bonds will take the first hit when underlying loans fail to pay interest and principal in full and on time.

In the case of the Destiny Mall deal, JPCMM 2014-DSTY, the S&P and KBRA AAA-rated tranche accounts for half of the $430 million deal (excluding interest only securities). A credit event that forces a write-down of the underlying mortgages by more than 50% will trigger losses on the AAA notes.

While unlikely, such an event is hardly unimaginable, especially given the large number of dead malls dotting the American landscape. Isolated shooting and stabbing incidents – even at the height of the shopping season – probably won’t deliver a large blow to Destiny USA, but if the mall gains a reputation for danger, shoppers will inevitably begin to avoid it. In a weak environment for brick and mortar retail, reduced foot traffic could trigger store closures, leading to a downward spiral of fewer retailers and fewer shoppers.

Without diversification, the senior CMBS notes are vulnerable to default under these circumstances. Facing such a highly plausible default scenario, the senior notes do not justify a rating of AAA – an ultra-safe category for which default should be virtually unimaginable. S&P, for example, claims it expects AAA bonds to have a default probability of 0.15% over any 5-year period.

Why would any rating agency believe a single property, even with multiple businesses on this single property, should have such certainty that a loss of greater than 50% of asset value is virtually impossible? KBRA, for example, acknowledges the low diversity of SASB CMBS but asserts implicitly that its stress assumptions for net cash flow and capitalization rate are sufficient nonetheless. Yet the stresses at the AAA level apparently do not permit the model to reach 50% loss. Et voila, it’s possible to reach the AAA rating with 50% or lower LTV.

While S&P and KBRA maintain AAA ratings on Destiny USA mall bonds, two other rating agencies take a more critical view of the facility. Both Moody’s and Fitch rate municipal bonds supported by mall revenues. In June, Moody’s downgraded these securities to Ba2 – a speculative rating – citing Destiny’s challenging operating environment. Fitch also downgraded the bonds to BBB concluding that “a recent trend of weaker performance … is likely to reduce the mall's value.”

The top ratings from S&P and KBRA are even harder to comprehend since the CMBS are subordinated to the municipal bonds to which Moody’s and Fitch assign the much lower ratings of Ba2 and BBB, respectively. These municipals are secured by “Payments In Lieu of Taxes” (PILOT) from the mall. According to the Official Statement for these PILOT bonds: “The 2014 CMBS Mortgage securing the 2014 CMBS Loan is subordinate to the PILOT Mortgages securing the PILOT Bonds (Page 4).”

AAA ratings for CMBS bonds that are subordinate to Ba2/BBB municipal securities are very hard to fathom. The distinction of CMBS versus municipal bonds is irrelevant since Dodd Frank’s Universal Rating Symbols mandate requires that rating agencies maintain equivalent meaning of rating symbols across different asset classes.

A dozen years after the financial crisis, rating agencies remain a weak link in the financial system. We don’t know when the next financial storm will occur or what it might look like, but overrated commercial mortgages are clearly a vulnerability. Before the clouds start gathering, rating agencies should take a harder, more skeptical look at deals collateralized by shopping malls and those collateralized by a pools lacking in diversity.

--------------------------------------------This piece was written by Marc Joffe and Joe Pimbley, who both consult for PF2. Marc Joffe is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Reason Foundation. Joe Pimbley is the Editor of the Journal of Derivatives.

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2rEnLWi

0 notes

Text

Lawsuits "Without Merit"

Theranos

Hero-turned-villain Elizabeth Holmes is once again the talk of the town, with HBO's documentary Out for Blood in Silicon Valley bringing her into our living rooms. (A feature film, Bad Blood, will be coming soon, starring Jennifer Lawrence.)

Back in 2015, Forbes listed Holmes as one of America's Richest Self-Made Women, with a net worth of $4.5 billion. Now, Holmes' net worth is closer to zero, and she awaits her day in court -- facing fraud charges -- while Theranos, the $9 or $10 billion company she "built" is now defunct. (Dollar numbers based on valuations/private fundraisings at its peak.)

1MDB

Meanwhile on the other side of the world former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib's trial has begun.

Most of the charges laid against him concern the siphoning of monies (billions!) from the state development fund, 1MDB. Some of those monies are alleged to have found their way back to Najib and his wife. Much of the rest seems to have been spent, and often wasted, by the energetic and now notorious Jho Low, who bought yachts and houses, Christal bottles of champagne, jewelry (for models), threw parties and otherwise lived the life of the rich and famous alongside his good friends Jamie Foxx, Leo Di Caprio, Paris Hilton, Pharrell Williams and other celebs.

But some of the 1MDB monies also found their way to Goldman Sachs and its prized individuals. (Goldman would confer honors on those individuals.) Goldman Sachs partner Tim Leissner has since pleaded guilty to bribery and money laundering. While Goldman made (an outrageous) ~$600 million out of the 1MDB issuances, Leissner pocketed some $40 million + just for himself. Good work if you can get it.

Cases Without Merit

Bringing this all together, what's interesting about Elizabeth Holmes and Goldman Sachs is that the allegations made against them are "without merit" -- they assure us.

In May 2016, when Theranos was hit with class action lawsuits, Theranos was quick to explain to the press that: "The lawsuit filed today against Theranos is without merit," she wrote in an email. "The company will vigorously defend itself against these claims."

When Partner Fund Management LP, a hedge fund based in San Francisco, sued Theranos in October 2016 for a "series of lies" and material misstatements, Theranos told the Wall Street Journal that this lawsuit “is without merit and Theranos will fight it vigorously. The company is very appreciative of its strong investor base that understands and continues to support the company’s mission.”

Walgreens also sued. You can predict this one: Walgreen's lawsuit, too, was "without merit."

When the Malaysian authorities filed criminal charges against Goldman, in December 2018, Goldman was quick to dismiss them, reassuring its shareholders. “We believe these charges are misdirected and we will vigorously defend them and look forward to the opportunity to present our case. The firm continues to cooperate with all authorities investigating these matters," the bank said in a statement.

Other Lawsuits Without Merit

Some cases, of course, have no merit. Others have merit.

But the question we ask is what confidence shareholders can draw from prepared, public statements made by companies that the lawsuits against them have no merit? If companies roll out a standard defense, reassuring shareholders that no major liability lies before them, can shareholders be assured that this is a truthful statement, as opposed to simply a negotiating technique?

Holmes and Goldman might well successfully defend the actions against them. Who knows - stranger things have happened. (The Theranos and 1MDB sagas, themselves, are pretty out-there as occurrences go!)

But whether they win or not, Theranos is done and dusted: it has been shut down. Goldman, meanwhile, has suffered significant fallout in its Malaysian operations: Goldman is struggling to get any share deals done, and has reportedly dropped to 18th in the local M&A deal rankings.

We pulled together an enlightening list of some (handsome) settlements entered into by financial institutions in the near aftermath of dismissing cases against them as being meritless -- and having promised to vigorously defend them -- only to settle for large amounts, sometimes soon thereafter. (emphasis added)

via Blogger https://ift.tt/2YOizuF

0 notes

Text

Lloyd v. Google

If it were simply a play, Shakespeare might have called it "Privacy, or What You Will." On Friday, the Wall Street Journal broke just the latest story, its lens aimed on Facebook, concerning the all-too-fluid movement of smartphone users' information from (other) apps to Facebook.

"It is already known that many smartphone apps send information to Facebook about when users open them, and sometimes what they do inside. Previously unreported is how at least 11 popular apps, totaling tens of millions of downloads, have also been sharing sensitive data entered by users. The findings alarmed some privacy experts who reviewed the Journal’s testing."

According to the WSJ's tests, heart-rate monitoring apps were sharing users' hearts rates with Facebook. And period-and-ovulation tracking apps "told Facebook when a user was having her period..." (As you might have guessed, much or all of this intra-app sharing reportedly occurred without the user's consent - the apps share the information with Facebook, but do not share the with their users that they will share their information with Facebook. And so, consumers come to realize that they are the product, not the customer.)

Why would Facebook care to know? One answer is that if Facebook understands its users better, it can send them more targeted advertising. If you're known to be pregnant, you're perhaps more likely to click on diaper or baby-crib adverts. (This is, ostensibly, a benefit to Facebook's users, who enjoy receiving advertisements more likely to be of interest to them. Ostensibly!)

Lloyd v. Google

The "key" to your online data - unsecured

Over the last few months, we have been researching an interesting lawsuit (and ruling) out of London. The lens in that case was focused on Google, but many of the issues were similar. In the Google matter, Google was alleged to have found a way around Apple's safety guards, imposing its own third-party cookies on Apple users' iPhone devices - so that Google could track iPhone user's web activities.

When looking into online privacy-related actions in the UK, at least 3 interesting similar examples came to light, in each case with the U.K. Information Commissioner’s Office (the ICO) leading the charge in fining entities: