Text

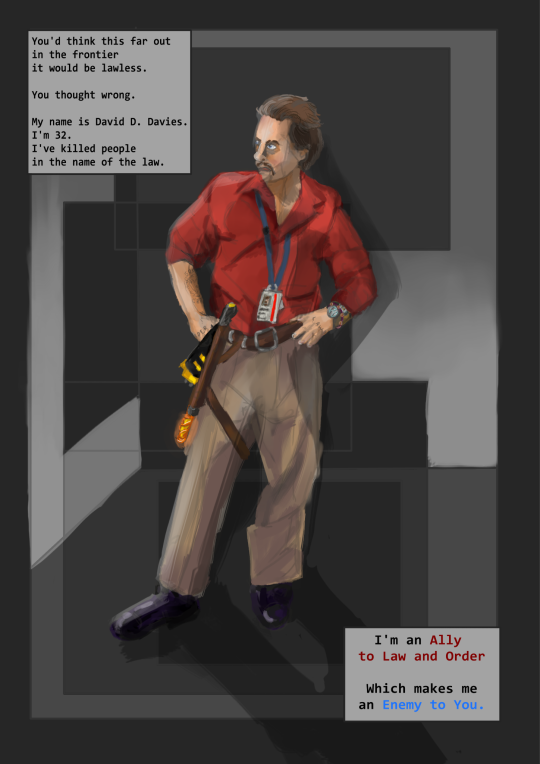

If I spend one more moment researching chemical terrorist attacks for Enemy to You I'm going to end up on another watchlist

0 notes

Text

They say a child was born on Christmas day...

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm not dead, nor is the Count the Days universe.

As some if you might know, I have an autoimmune disease (nobody’s figured which one yet, even if its a distinct one) which affects my brain. Whilst I'm incredibly lucky it's not done severe damage, I do have epilepsy now.

One of my first seizures went on for several minutes and I struck my head on my sink (and yes my landlord took my deposit for the chip out of it) Ever since then I've had something called anomic aphasia, since the seizures come from my temporal lobe- I know what I want to say but the words aren't making their way to my mouth or hands or pen.

I am seizure free now with medication, and I've learned to find this funny, as well as ways around it but it slows me down somewhat.

HOWEVER. That being said. I'm hoping to complete the first book in a three or five book series in the count the days universe. That means that there's a period of a lot of plotting, worldbuilding and general insanity to get through. But I'll get there, and I'm determined to get the universe I've had for the past ten years into a published book.

Happy travels!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flowers

A re-write of this scene. Contains vomit, gore, blood, mentions of animal cruelty, field medicine and passive suicidal ideation. Sorry Fennec (again)

---

His heart is beating so hard it hurts. He pelts through the forest,the dappled light playing over him. His ID card has come undone, the pin stabbing into his collarbone over and over, but he doesn’t have time. There's no more time. The papers in his pockets crumple every stride he takes, his signature on the orders, his name on his own death warrant.

But he doesn’t want to die. Not here. Not like this. Not scared, not so far from home. Not alone. Not in pain.

Please, not like this, and that's the mantra that keeps him running from the State soldiers not far behind. He tried. No quarter, they said, and knelt him down to put two in the back of his head. Their commander interrupted. He thought he was saved.

The officer gave him a three minute head start in a fox hunt. He is the fox. He is going to die like one too, he thinks, unless he keeps running. All that matters is that he keeps running-

Searing cramp shoots from his foot up his leg. He screams, stumbles and hits the ground, scrambling on bruised knees and grazed hands, and feels the horrible heaviness of bile rising in his throat again. He claws his way to his feet against the bark of a tree, clamping his jaw shut to keep himself from vomiting. It doesn’t work, an acidic stream erupting from his nose instead, and finally, he succumbs to it, and throws up into the mud. He doubles up, a hand on his chin, tears streaming down his face, spit trailing from his beard.

His muscles are on fire. He is on fire. Part of him wants to lie down and wait for them to catch up with him, wait for them to sit him up and cut his throat, or to meet his end with fibre wire and a hand over his mouth. If he's lucky, to be double-tapped and watch a round tear through his chest before the one through his head finishes him off.

But he knows he can't. He's too scared. He wipes his mouth and forces his burning self onwards. Steps become walking becomes jogging becomes running with the taste of vomit in his mouth. He breaks out of the forest and into a meadow. The ground hardens a little beneath his feet. He glances behind him and sees nobody.

Maybe, he dares to hope, he's gotten away. A smile cracks across his sweat-drenched face. A cool breeze rustles through the meadow, across the balmy blue sky. His running slows into a jog. The smile broadens as he glances behind again, and starts the slow jog towards the far treeline.

“Not today,” he gasps, winded, the same smile on his face. “Not-”

The words are ripped from his tongue abruptly. From a place he doesn't see comes a shot he doesn't hear. A high calibre bullet carves the air apart. He just happens to be in it's way. Immense speed meets soft flesh. Speed obliterates it, carving a path through him, throwing blood and bone and muscle out behind him.

The shattered bones give way and the force of the bullet carving through his leg knocks him off his feet. His brain is yet to process the pain. It simply feels like he has been hit by an invisible wave, an unseen force tossing him backwards. His torso and hands go one way, breaking his fall in one direction, and his legs go in the other- and for a moment, he thinks he is split in two. Like he has been hit by lightning- one moment he is upright. The next he tumbles head-over-heels, and then the last, he hits the ground with a bang. Ribs crack. A spray of blood arcs over his head- somehow, it ends up on his face, in his hair. It takes a moment to work out what has happened. He looks down, and then heaves a dry retch as he looks at his leg. It looks like it is hanging on by a thread of shattered bone and gristle. There’s so much blood. He can’t believe how red it is.

“No!” he cries out quietly, drawing out the last syllable into a little howl, a quiet protest at the universe. He gasps for air to try and calm himself down. It doesn’t do much- his eyes are fixed on his ruined leg, on the bright red blood spreading in a pool beneath him- and his mouth goes dry when he realises it’s not that just he may never walk again- he is actively bleeding to death.

It still doesn’t hurt yet. He thinks maybe he can walk on it. He claws at the mud, pushing one foot into the dirt and pulling with all his strength. He bears down on the other, and then feels something break inside of it- an almost audible crack, with the overwhelming sensation that may as well have been a baseball bat to his head.

He is proved wrong on every count. He can’t walk. It hurts. It hurts like hell. He puts his fingers against his leg, and for some reason, claws at it, wondering if he can distract himself enough to be able to crawl. Fennec is again proved wrong- he moans, bearing his teeth, feeling his fingers go into his bone and his muscle. Paper, the lower half of his leg is little more than paper, and as he tries again to bear down on it, to get to his feet, the noise of something snapping like a twig is unmistakable. A noise tears from his mouth- an animal howl.

He bears down again, pushing himself to his feet, and then lurches forwards, falling down into the dirt, his good leg slipping in the mud. He gets nowhere. Again, he puts his hands in the mud and pushes himself up to a position where he can half-crawl, half-drag himself along the ground. Behind him, a snaking trail of blood runs over the drought-parched ground, swirling into the dirt. He slips again, his elbow giving way, and this time, lands on his knee. Something snaps again. His vision goes white, almost, then black around the edges. He realises he isn’t breathing- he isn’t remembering to- and gulps down the cold morning air like a fish out of water.

He goes from crawling on hands and shattered knees to lying on his side, howling at the top of his lungs, almost as if he is no longer the same as his body. The noise that comes out of his mouth barely seems like it’s coming from him. The flowers remain silent. It passes after what seems like an eternity. He rolls onto his back and puts his hands beneath him for a moment. He didn’t think that that simple movement would hurt him. It does. His shattered knee rolls over along with him, and the next phantom blow takes him out.

The white-out is tremendous. The black seeps in again as he forgets to breathe. When he gasps for breath again it is laboured. The blood has turned what is beneath him to mud. There’s bile and tears and snot all down his jumper. Cracked glasses, cold fingers and toes, and the only heat is what leeches from his leg. He looks a picture of utter dread- staring into the middle-distance, he sees his own death rapidly approaching.

He is going to rot there, he thinks. The flowers will eat him away into nothingness under the rolling grey sky. His wife will never know what happened to him. All Alais will know is that he is gone and he is not coming back when the officers show up to their little cottage with their caps in their hands and paperwork and condolences.

The flowers remain silent. His unborn daughter, Sabine, she will grow up without a father, and he will die here, in the middle of this field, far from home, with the slate-grey storm rolling above and the flowers swaying gently around him. He will rot, like he’s seen deer carcasses rot- his skin will slough off, eaten by flies and maggots and animals, and then his bones will stare up into the disapproving sky until their putrid brown is bleached to ivory white.

He starts to sob, and still, the flowers remain silent. It’s not fair, he thinks. He tried. He really did. He tried and he’s still going to die. The tears quickly pass. Something fills him, an uncanny calm as if it’s being poured into him like water. He puts his fingers at the edge of the hole in his knee, wipes his face and lies back in the grass, staring at the sky. Waiting to die.

He undoes the top button of his shirt, leaning back into the cool earth, and feeling the warmth pour from his body and into the earth. The sky that he is beneath is the same Alais will look up at- they will never be apart, not really, as he soaks into the earth and his atoms return to feeding plants and animals and seep into the watercourse- because nothing is ever created anew, and nothing is ever really destroyed, they will never be truly separated- and the more blood that leaves him and soaks into the earth, the more he knows he is okay with this, he’s okay with this, he’s okay with this.

But this is not what happens.

No, that is not what happens, and he laments that fact, sinking deeper and deeper into the uncanny calm. Even as the dark green uniforms of the Rangers fill his hazy vision, he can’t find enough care in him to react. He just stares at them, silhouetted by the sky. They kick his sidearm away from him, and his knife, and pull something from his pack. Fennec looks at it and realises it’s his haemorrhage control kit. All he can remember from the classes where they taught him how to use it is the smell of wood polish. The rest is lost under the smothering blanket of the peace that threatens to drown him. The earth beneath his back is cool. He is getting colder.

The Ranger apologises to him, pulling something out of the trauma pack. Catastrophic bleeding from the leg can be stopped temporarily when the femoral artery is compressed enough by the tourniquet further up the limb than the open wound. No more blood can get to the wound and no more blood can get out. It is well renowned for being painful. To a patient who is conscious and aware of what is going on, it can be explained and braced for. Fennec can’t fathom why the man would apologise. For what, he thinks. Apologise for what? Not for this. Not for this feeling. This beautiful feeling. He does not understand it, and he does not brace for it either- just watches distantly as they apply the tourniquet- until they tighten it.

The bleeding stops. The agony takes him by surprise. The white-out comes again. He can hear himself screaming and yet cannot make himself stop. All he knows is the notion that it must stop. It must stop. He screams, and screams, and screams, trying desperately to slam his head against the ground, arching his back, clawing furrows into the dirt with his fingers and kicking an arc into it with the heel of the shoe that isn’t completely drenched in blood, the sky’s pallid blue glancing off of broken glasses lenses, yet, though he tries with all his might to knock himself out on the ground, it never happens.

He writhes in agony, screaming and howling, kicking out weakly with blood-soaked trousers and his good leg, drawing his hands up to try to hit himself in the face just to feel something else in the hopes that it would lessen the feeling that the pain is shredding his very personhood into tiny little pieces. He can make no words, no sounds but the screaming.

When it is over the flowers are silent still. He catches his breath, chest heaving. The dressing being packed into the wound barely makes him flinch as he comes back to himself still hazy. He winces as the skin pen touches his forehead, writing the time below a letter T in blue-purple ink.

He thinks he will never know pain like it ever again. In fact, he would come to be good friends with it. He has the rest of his life to get to know it- in the dead of night, he would have many a conversation with it- and it would be like an unwelcome guest in his house lingering to the morning. But there and then, in the meadow- he had never once felt something like that before. He didn’t think it was possible.

But now he knows.

#original writing#whumpblr#anton fennec#writeblr#count the days#writing#verschlimmbessern#original content#yeah#tag moment

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

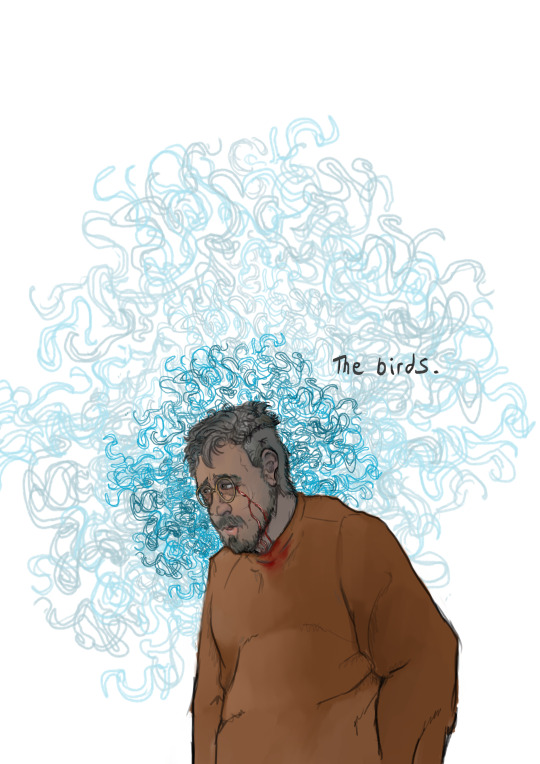

The Birds: 1-2

Previous - Next

This whole series contains body horror and themes of mental illness, self harm and suicide.

---

He sleeps just long enough to wake up to the sedatives wearing off. He feels like he is falling through space, down through the mattress, over and over and over, a sickening feeling. Drenched in sweat, his jumper beneath his head damp from his own saliva from when he was asleep, he grabs onto the flat sheet beneath him and tries to focus on anything but the sensation of falling.

The door is unlocked and he hears two sets of footsteps walk it. “Mr von Fennec, your presence is requested,” says a woman’s voice, echoed by an interpreter. He peels his damp cheek away from the sheet and looks over his shoulder. The woman stands with her arms crossed, blonde hair scraped up into a bun. Two soldiers in urban uniforms- smartly-ironed blacks and greys, radios and key chains- flank her, and to one side, a man in a dark green uniform- the interpreter.

Fennec grabs at his glasses and slowly puts them on. “Who?” he croaks, voice barely audible. The interpreter steps a little closer to him, positioning himself between Fennec and the woman to be able to hear them both. Fennec looks her up and down, squinting at her shirt collar to try to make out the silver insignia badges pinned to both sides.The insignia on her shirt are of a greek letter psi.

“I want to speak to you.” He realises she’s wearing lipstick when she talks.

That tells him nothing. Her clothes tell him frustratingly little as well. She’s wearing sharply ironed dark grey trousers and a short-sleeved lighter grey shirt. On her belt she has a pen, a pupil torch, and a pair of handcuffs. “And who are you?”

“Psychiatry,” she says.

He presses his cheek back to the jumper he has folded beneath his head. “Not interested,” he says. “Take me off of your list. Thank you.”

“Give me a good reason, please,” she says.

“I have no further means to kill myself nor can I expend the energy to kill myself.” He buries his head into his jumper. “I am not a risk to myself. Therefore there is no need for you at present-” he begins, and she gestures to him with a glance at the two men either side of her. They grab him under the arms. He exclaims, surprised, as they pull him to his feet. He grabs onto the closest person’s arm to try to steady himself, but his knee gives way anyway, and he sits down on the edge of the bed before he falls. “Won’t you leave me alone?” he exclaims angrily. “I’m exhausted!”

She tuts. “So despite what they’d have me believe, you really can’t walk.”

He shakes his head. “I need my crutches.”

“You’ll be using the wheelchair. I’m handcuffing you.”

He flicks bloodshot eyes up to her face. His gaze is quickly dragged back down to the floor. “They don’t do that. Just a long chain. I use my crutches,” he mumbles.

“I am not whoever ‘they’ are.” She motions for his hands, taking the cuffs from her belt. “The risk associated with you has changed.” He looks at her with a look of betrayal and holds out his hands, wrists together. Bruised fingers taped to unbruised ones tremble gently as she tightens the cuffs around his wrists.

One of the soldiers pushes a beaten-up wheelchair to the edge of his bed and kicks on the brakes. Fennec shifts his weight to the edge of the bed, and with the psychiatrist’s hand beneath his arm. He sits down in the wheelchair, wincing as he shifts his bad leg up onto the footplate. The chain of the handcuffs clinks against the side of the wheelchair. “Let’s go,” says the psychiatrist.

Fennec looks around, drinking in his surroundings as they lock the door of the cell behind the small party and start to wheel him down the corridor. The walls are pink- he remembers that, even through the blurry haze of the past few days- but it occurs to him now that this is Schauss pink - a particular shade associated with reducing aggression and agitation. The ceiling is white asbestos tile, harsh fluorescent lights and mirrored domes to hide the ever-present gaze of the cameras.

The corridor opens up into a small area with a gantry overhead, a set of gates passing alongside a large glass-fronted security post, and a number of tables and chairs. The psychiatrist walks to the closest table and sits down. Fennec finds himself opposite to her, the brakes on on the wheelchair. The interpreter sits at the end of the table, perpendicular to them both. Fennec glances at him to make sure he is sitting down before he begins. “Here?” he asks, glancing around the open space. His voice barely sounds like something he recognises. Each time he swallows his own saliva after talking it hurts.

The psychiatrist opens her bag, a leather satchel and starts spreading the contents out in front of her. “You’re on the condemned wing. Nobody comes in. Nobody goes out.”

The word condemned rattles to the front of Fennec’s head. He lets it sink in, staring blankly across the table. He’s too tired for this, any of this, he thinks.

The psychiatrist takes her pen from her belt. “I want to talk about the suicide attempt.” Fennec resists the urge to point out the redundancy of the statement. Of course she is. The psychiatrist pulls out a clear plastic evidence bag and holds it up to him. In the crumpled evidence bag, Fennec looks at something which he recognises as the knotted and bloodstained remains of the strip he tore from his blanket, cut into four frayed pieces. He turns his head to stare at the grey floor. She sets the bag down on the plastic table. “Was this what you used?”

Eventually he finds it in him to speak. “Yes.”

“Did you tear it by hand?”

He nods slowly. “Yes.”

“So you had no blade?”

“Well, I assume you looked, and didn’t find one. Now you are concerned.” He shifts back in the wheelchair, leaning back, stifling a pained cough. “I had no blade, no weapon or scissors.”

She pauses to write something on the form in front of her, before tapping her pen against the table. “Why’d you do it?”

Such a vast question, he thinks, and yet he can’t quite pin down an easily summarised reason. He tells the truth. “I don’t know.”

“What was your disagreement about with my colleague just prior?”

Fennec notes that she calls the faceless man only her colleague- no name. Perhaps the man simply doesn’t have one. “It was an argument over my testimony,” he says quietly.

She keeps writing. Fennec winces at the noise of her pen against the paper. “You’ve agreed to appear as a witness for the prosecution in the Horatio trial?”

“Yes.” He brings his hands up to his face and fumbles for a moment to push his glasses up his nose with a sigh. “I don’t want to. I know what I say is enough to damn my former colleagues. I cannot lie because they already have me on record repeating the truth over and over to save myself. I remained out of options, out of time, and I thought that I could avoid it if I were dead. The rest is known.”

“Where do you stand on it now?” He says nothing. She taps her pen against her lips, letting them sit in silence for a few moments, before speaking again. “Is this an attempt at being adversarial?”

“Yes,” he says simply, barely above a hoarse whisper. “You’re asking questions and you know I have no choice, don’t you?”

She keeps taking notes, and then clasps her hands together. The clear varnish on her nails catches the light. “Do you feel as if you have been treated unfairly, Mr von Fennec?” she asks.

He laughs bitterly. “I’ve been tortured. I’ve been shot, I’ve been beaten, I’ve been raped. All through that I’ve said what I was told to say, done what I was told to do, been what you want me to be. I confessed. I gave you everything I knew. I let you convince the world I was dead.” He leans forwards, fixing his gaze to hers. “After all that, you know really, really gets to me?”

She continues writing, biro letters spiralling across the page. “What’s that?”

“You people still think I’m a threat.”

That grabs her attention. She looks up from her papers. A grim smile plays across his face as he leans back, shaking his head. “It’s not me versus any of you. I lost whatever game we were playing a long, long time ago. You’ve had me in checkmate ever since I surrendered.” He turns his head to one side, shakes it, and then turns back to look at her, a sort of sadness in his eyes. When he speaks again, he is even quieter, calmer- almost deadly calm. Transformed from a still sea to the uncanny calm waters before a tsunami. “Well, I’m not playing anymore. I’ll testify at the Horatio trial and then I am done. I am out.”

She finishes writing with a full stop and then clicks her pen, tucking it into her top pocket. “Alright, Anton,” she says. “I think I’ve heard enough. Thank you for your time.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

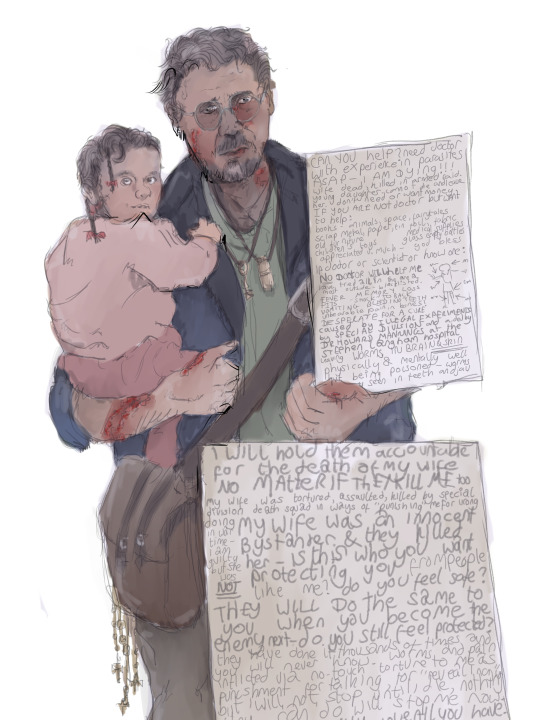

How could you cope with knowing it was your fault? Surely, then, the agonies of your delusions were more comfortable than knowing you would never be punished to the degree you deserved for letting her die? - "But for God's sake, for the sake of all that you love, don't bring my daughter into this. I'll kill you. I've got nothing to lose anymore. She's all I have left."

#cropsey#<- the title of this au btw because i think I'm not done with it#both the urban legend and the have a nice life song#also yes not to be the ao3 people but they've diagnosed me with epilepsy and the anticonvulsants are giving me insane dreams which is#how come the insane au spawning has resumed. i am fine btw just bruised and missing a part of my tongue

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Birds: 1-1

Previous - Next

This whole series contains body horror and themes of mental illness, self harm and suicide.

Finally getting this started. Progress will be slow. Having trouble doing anything creative since I had the seizure but I'm giving it a go.

---

The corridor is long, low and windowless. Every man held there is awaiting his own death. The walls are painted a particularly sickly shade of pink, more suited for a nursery than the condemned block.

The guards can be heard before they are seen. Their keys rattle on their chains. A woman carrying a folder under her arm walks a few steps ahead of two black-shirted men escorting a prisoner. The prisoner between them can barely walk. They have to drag him. His feet slide along the floor- cheap white trainers. Cuffed hands hang loose in front of him, bruised fingers with broken nails taped together, and the grey jumper barely grazes his wrists, several sizes too small for him. He has forgotten how to close his mouth- his tongue is pale but marked with angry red where he has bitten it. A thin string of saliva twists from his beard and drips onto the floor. His glasses, held together by tape at the hinges, seem to barely cling to his face.

With a moan, he tries to swallow his own spit and coughs and splutters. The woman reaches into the pocket on his trousers, taking out a balled-up tissue and wipes his mouth. He dribbles onto the tissue, and tries to focus on what’s in front of him, bloodshot eyes tinged a pallid pink flicking across the corridor. Briefly, he takes a few steps, before collapsing again under his own weight. They continue to drag him.

The woman stops in front of the grey doors and unlocks it with one of the keys from her belt. The cell smells of bleach, whitewashed walls and grey lino floor. There is nothing in it save for a stainless steel sink and toilet unit in the corner next to the door, and the bed in the far corner. There are no sheets on the bed, just the flat sheet over the mattress.

The man lifts his head a little to stare into the cell. The officers on either side of him take most of his weight. He pitches forwards, unaware of his own centre of gravity. He furrows his brow. “Where’sit,” he slurs, gesturing weakly with cuffed hands to the empty room.

“Where’s what?” she asks. “Your belongings?”

He grunts in agreement. “My pencils. Photographs, m’ books.” His worried eyes flick over the room as if he is expecting his belongings to suddenly jump out at him, to materialise in an empty corner. They don’t. Tears start to well up in the corners of his eyes.

She puts a hand on his shoulder, leans over and undoes his handcuffs. His wrists are marked, patterned like crumpled paper with indents from straining against much heavier restraints. “Shall we go and sit down on the bed?”

He ignores her for a moment. His hand goes straight to his neck, to the angry red and black bruises, before the heaviness of his own body becomes too much for him to bear, and the hand drops, fingers getting caught in the collar of his jumper on the way down. He tries to say something and it comes out as an incoherent groan. She puts a hand in the small of his back and tries to push him forwards a little. “Shall we go and sit down on the bed?” she asks again.

“Mmm.” He takes a step, supported by her, locking his knee and dragging his left leg. His hands go out to keep his balance, but he takes another, limping in the same way, and sits down on the edge of the bed. Still he does not shut his mouth, the trail of spit starting to drip from his beard again. He looks down and rubs the fabric of the flat sheet between his fingers, utterly absorbed in the way the fabric brushes against itself. He tugs it up a little more, and something beneath the mattress catches his eye. He tugs at it, once, twice, three times, until a little more of it comes loose. He studies the heavy fabric with holes punched through it for a moment, before he holds it up to her, that same anguish-tinged look of open-mouthed confusion on his face. He says nothing, just looks at her.

“Those are restraints, Anton.” She sits down beside him, putting a hand on his arm. “To keep you safe. But we don’t need those right now, do we?”

"Don't know." He wipes his mouth on the back of his hand.

She keeps her hand on his arm. "You're safe. You won't hurt yourself again. That's for your own good."

There is a pause as he turns it over in his mind. “I don't know anymore,” he breathes, and holds his own shoulders tightly. “I don’t want to do this anymore. I don’t want to BE this anymore.” He looks at her with eyes full of tears. “I want to go home,” he says, slurring his words. “I want to see my wife, my daughter, I want to go home,” he repeats, and a tear rolls down his cheek.

“That’s not possible right now. You sound very tired.” She takes the tissue from his pocket again and wipes his mouth, and then the salt-stains from his cheek. “Are you going to sleep?”

“Yeah,” he says, sniffing, and lies down, lifting his left leg up onto the bed with a hand underneath his knee. He pulls off his jumper and tucks it under his head as he rolls onto his side. He fumbles with his glasses with taped-together fingers to take them off, and hooks them over his lapel. She sits there for a few moments, watching the rise and fall of his chest. When he starts to snore she gets up with a hand on her keys to stop them rattling.

She locks the door behind her.

“Jesus Christ,” says one of the men, arms folded across his chest. “What a fucking mess.”

The woman tucks her hair behind her ear. “Some of them drool like that with the sedatives, some of them don’t.” Sifting through the folder under her arm, she pauses for a moment on the full audit record of his injuries. “He’s probably too sore to swallow that amount of saliva.”

The photographs were all taken with flash in the early morning. The motion is evident from them, someone having to pull his fist apart to straighten out his fingers, tension in his arm from tugging against the leather limb restraint around his wrist. The next few are of his bloodshot eyes under a pupil torch, three photos in quick succession, his face twisted into a picture of childish distress as someone gently opens his eyes with nitrile-gloved fingers despite him fighting to keep them shut. The rest are all of his neck. He is sat up for those, co-operating, turning his head this way and that, someone brushing back his mousey-brown hair from his neck to show the ligature marks around his throat, the deep red and black bruising. She wonders how the nursing team managed to get him to play along, and turns to the next page in the folder, her order form for an adapted diet. “I’ve signed off on a soft diet for the next week. Make sure he gets that or he won’t be able to eat. He’ll need a minder for a while.“

There’s a loud tut from the man in the black shirt. “That’s a member of staff I’ve got to waste on watching a single man who’s just tried to top himself.” He bristles, expression souring, rocking back and forth on his heels. “How long are we expected to do that?”

She smiles, knowing he can’t weasel his way out of the responsibility. “You can stop assigning a minder to him and watch him on the camera when he’s not doped-up enough that he might choke on his own spit in his sleep.” She turns another page in the folder and comes to the form she filled in giving them the option to keep him restrained for the maximum of six hours. “If he gets agitated you can use the Pinels under the mattress. I’ve signed off on them already for the grace period. If you can’t de-escalate enough to de-restrain him in the six hours, call me. I’ll get a court order to keep him restrained or I’ll send someone down to sedate him again.”

The officer shakes his head, arms still folded. He looks at the locked door, and then back to the woman. “I’m not happy about being lumped with your headcases, Marie. This is the condemned unit, not psych. My guys generally don’t try to speed things up when it comes to being dead.”

“Well then,” she says. “You better hope he agrees to testify, or you’ll be stuck with him until they take him out to shoot him in the back of the head.” She picks out a stapled booklet of papers from the folder and slots the papers into the clipboard beside the door.

The first is a blood-red sheet, bold capitals across it - ANTON ELLMENREICH VON FENNEC - SUICIDE RISK - MANDATORY 5-MINUTE CHECKS.

Beneath it, on a second clipboard, his photo stares into the hallway- dishevelled, confused, with cracked glasses. If you asked him, he’d say he couldn’t remember when it was taken. He forgot several months ago.

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

I think the readmore on the prologue is missing/broken!

auuuu yes it is thank you. i've added one in again.

0 notes

Text

The Birds: Prologue

Next

This story contains themes of suicide and mental illness from the very beginning. This piece also contains sexual themes and is not appropriate for minors.

---

He parked the car towards the far corner of the car park. The trees play light off the car windows, the moonlight and the white streetlights mingling into a pale wash. In the driver's seat he sits and stares into the middle distance. He feels like wax, slowly melting, chipping, peeling away. There is not really a different way to describe it.

He is not depressed, he tells himself. When he sees people who are sad they do not look like he does. Sadness is blue, or grey, it hangs around people like mist or dust. This feeling to him was always a dark oil-black, coming from his very bones. At home, coming home, on deployment, miles beneath the ocean or miles from land in the middle of it - it doesn’t matter. At first being out at sea made him feel better. Now it makes no difference. The feeling is always there, subtly dragging him down, like black mould creeping in on plastered walls. It isn’t really sadness, he thinks. It’s like he’s rotting from the inside-out.

He doesn’t really remember the last time he didn’t feel like this. He takes the key to his gun-safe from the leather necklace he has on and rubs his thumb over the number engraved on it. The curiosity that seeps into him isn’t a bright clear blue like normal curiosity- it’s tinged with brown like dried blood. He wonders what it would be like if he shot himself here and now.

He doesn’t really think about what he’s doing as he puts his key into the lock and turns it, opening the gun-safe. His pistol is there as it always is. He still doesn’t really think about what he’s doing, still engaging the soured curiosity. He puts the key back around his neck, and loads the pistol, racking it. He holds it in his hand and feels the weight of it. I’m not trying to kill myself, he tells himself, I’m not trying to kill myself. I just want to see what it would be like if I did.

Engaging the part of him he likes to pretend isn’t there, he puts the gun in his mouth.

The pistol is cool against the roof of his mouth. He sits there for several moments, with his finger on the trigger, and tries to absorb everything. It would be so easy, he thinks, and then the moment of clarity hits. What the fuck am I doing, he thinks as the shock hits him like ice-water. Disgusted by himself, he pulls the gun out of his mouth, spitting down his front as he puts the safety back on, holding it at almost arm’s length.

He puts the gun back in the safe as fast as he possibly can. He slams the gun-safe shut, and throws his keys to the back of the car, an arcing backhand throw, twisting around in his seat with a look of fear on his face. The keys smack into the rear window with a little clink, and then fall into the depths behind the seats. With his heart pounding in his chest he stares at the back of the car, fighting the instinct to run back there and start pulling apart the seats to get behind them and retrieve the key- his face crumbles the instant the unbearable restlessness passes. He takes his glasses off and sets them on the dashboard to wipe his streaming eyes on the heels of his palms.

He kicks the inside of the footwell. I can’t do anything, I can’t do ANYTHING, I can’t do ANYTHING, he wails. He kicks the wall of the footwell again, again, as hard as he can, until he can feel the throbbing of his toes through his shoes. Then once more for good measure, until it starts to really hurt, and then he stills, breathing heavy. His face is covered in a sheen of tears and sweat and there’s the dampness of saliva down his T-shirt. His mouth hangs open as he reaches for his glasses and puts them back on again, and then wipes his face on damp sleeves.

A few moments more pass in deafening silence. The wind outside is totally still, there is no noise, the car is well-soundproofed. He feels no better. With that, he reaches for the keys, and starts the engine, checking his mirrors to pull out.

---

The streetlights start to disappear only a few hundred yards down the road to Neunzing, a stark contrast from the well-lit autobahn and the light-bathed main roads. The town is sleepy during the day. At this time of night it’s stuporous. He indicates to pull into the driveway of the house that he grew up on- the house that is now his, starkly empty compared to the joy it contained when he was younger. The gravel crunches beneath his tyres. He turns his headlights onto their low beam as he comes around the corner. A deer once froze up in the middle of the driveway, startled by the high-beams of his car, and he almost hit it. Now he takes the corner much more slowly, one hand on the steering wheel.

The lights in the kitchen are on. He puts the handbrake on and kills the engine, but sits in the car for a few more moments. There’s the feeling of pins and needles in his hands as he rests them on the steering wheel.

Eventually he gets out of the car and hobbles around to the back, opening the back door and pulling the seats forwards. The key to the gun-safe shines in the moonlight. He reaches for it with a grimace as he bears down on his throbbing foot, but his fingers meet the metal and he grabs the key from where it has fallen.

He slips the key back around his neck and slams the car door shut as he straightens up. He lets himself into the house as quietly as he can and limps up the stairs, gingerly putting weight on his foot. He throws off his uniform coat the moment he gets into the bedroom. His wife appears in the doorway, leaning on the wood. Her nails are painted purple. Your dinner is cold. Her hair is in long, fine plaits, spilling down her shoulders, over her long shawl.

He shrugs. Schade, he says. I’ll microwave it.

Ant, she says, and shrugs her shawl off. Let’s have sex.

His mind goes blank. He just looks her up and down. Now? Are you ovulating? he asks. He has it marked in his diary, little asterisks on particular dates. They’ve tried and tried for a child and they will keep trying.

No, she says. But that doesn’t matter. It can be just for you and me. She drapes a towel over the couch and undoes her shirt, letting it fall off her shoulders. We can just have sex. It doesn’t always have to be for a purpose.

He looks at her standing there in her bra and then he looks away again. Alais, I’m sweaty, I’m tired, I- he trails off, shaking his head and shrugging. Without admitting what happened earlier to her, he can’t form a convincing case for being left alone after they’ve been apart for so long, so he doesn’t.

She takes a step towards him and runs the palm of her hand over his back. What’s wrong?

There’s a long pause. I really wanted to go to university, he says. I wanted to study art.

He feels the sweat on her skin pressed against the pallor of his. I know, I know you did, she says, and leans forwards so her head is under his chin.

His eyes start to water. I’m not crying, he says as if that explains everything. I’m not sad. It’s black as oil.

It doesn’t have to be sadness, she says.

But I’m not depressed, he says. And I’m crying all over you. What does that make me?

She says nothing more to him, just cups his cheek in her hand, and then he struggles with his trousers to get them off. He drops his belt on the floor and fumbles to take off her bra, tossing it onto the bed. They have sex, half-dressed on the couch. He doesn’t really enjoy it. He has to finish her with his fingers because he’s too numb to keep his erection. To him it feels like he is doing something bordering on brutal to her. He apologises to her throughout.

She tells him he should stop apologising. He’d article after article in his awkward years to learn how to have sex and still it didn’t really translate into practice. Years of marital experience were needed before he was even passable. Most of the time he laughs off his inaptitude. Now it’s all he can think of. The feeling that he has just done something terribly violating to her remains, even as she reassures him that nothing is wrong.

When everything is cleaned off, he throws himself down on the sofa and stares into space again. He still doesn’t feel better. He puts on the television, low, and just lets the light play across his face. There is nothing to say. She sits down beside him and he takes out her plaits, numbly picking them apart and running his fingers through her long, dark hair. Across the state a young boy has thrown himself off a railway bridge. The boy hasn’t been named. They never are. Wiping his nose on the back of his hand, he stares at the news program with glassy eyes. She falls asleep on his shoulder.

He carries her to be and gently tucks the covers over her. Glancing behind, looking at her with a bittersweet fondness, he turns the bedroom lights off and goes downstairs. He grabs his walking coat from its hook, lets himself out onto the patio, and in the dark, lights up a cigarette from the pack in the coat pocket. His foot has settled down into a dull ache. The stars above him are bright and clear, Mars tracks its way slowly across the sky, and the rest of space is so resoundingly, utterly empty. He exhales. His breath spirals into the dark and then dissipates like it was never there. He looks out across the forest, dark and silent. The evergreens look at him with distaste, they always have.

The forest is no more welcoming than the endless reach of black above him, or the warmth coming from the ajar door back into the house. Wherever he goes he drags the blackness too. He realises he has another sixty years of this ahead of him.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every knock on the door will haunt you, every little rustle of wind in the leaves, every passing car- every little glance at you on the street- it will haunt you, and haunt you forever- but you wouldn't have it any other way.

They will have taken you to pieces with everything that you could survive having done to you. You will have bled, you will have cried, screamed, and wept, and then you will have been silent. When your body started to give out you gave them your mind to stay alive and it will have barely been enough to keep them away from your broken body. It will hurt you forever, every waking moment, and some of your dreams as well. It will hurt forever and you wouldn't have it any other way.

You said that you would always remember them, and you will, but it will seem so little in the face of your betrayal. It will always be the thing that eats at you. You will always have fallen apart, you will always have been insane, and you would not have it any other way- because despite the pain that follows you relentlessly, despite your cowardice, despite all you have done, despite everything, you will come to love yourself, in one way or another.

You will, one day, come to love yourself again, and you wouldn't have it any other way.

#art#anton fennec#actual footage of me emerging from my room when the fire alarm goes off at 2am#ft a little sort of poetry#quinns poetry (real)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thirteen Frames

A Verschlimmbessern story. Following The Butcher And The Fool. Three weeks later, Fennec is discharged from the custody of the butcher. Contains depictions of institutional abuse, mild mouth gore, passive suicidality, implied torture and implied sensory deprivation.

---

He isn’t sure if it’s over or if this is just an interlude. The moment the interpreter sat at the table with him and the Specials he almost cried- frustration and relief and exhaustion threatening to brim over. He told them again what he had been saying over and over since they brought him here- I’ll do it, I’ll do it, I’ll do it. This time they listen- or perhaps they had been listening all along. He told the butcher it innumerable times in German, in broken English, in every sort of nonverbal communication he had- so they must have heard. They just chose to ignore him. He signs something and can barely get his broken fingers to grip the pen. He shakes nobody’s hand.

The Special who spoke to him at the start of this all offers him another can of coke after the paperwork is signed, opening it and setting it in front of Fennec- it is not easy to open a can with broken nails or broken fingers- who stares at it for several long minutes after the man has left and it is just him and the interpreter left. The coke is lukewarm. He takes a sip of it and then retreats back into his leaden body. He doesn’t really understand what has happened to him.

The moments are fragments, buzzing around his head. The last time he had a cigarette, the butcher gave it to him in silence. He’d shared the lighter with the butcher, and been relieved beyond relief the moment the nicotine hit- all a nasty habit but he really has never cared- that he had tried to thank the man in English. It was at that point the butcher had reached over and put his cigarette out on Fennec’s tongue. You don’t speak to me like that, he’d said as Fennec had spat blood onto the floor, apologising for something he didn’t quite understand. We’re not the same.

Even tasting the memory of ash in his mouth again, he wants a cigarette. Desperately. He finds himself salivating at the smell of second hand smoke in the room- every small space here he can smell it- and the ashtrays are dotted around- one in the middle of the metal table they’re sitting at, next to where the can of coke sits, barely touched.

Dignity was something he lost a long while ago, he thinks. He may as well take the opportunity. Slowly, he reaches over to the ashtray, picks out three or four cigarettes, and carefully field strips them, collecting the tobacco into a little pile, and peeling the most intact paper he can find apart, filling it, and then sticking it back together with his spit on his thumb and forefinger. He doesn’t try to salvage a filter, just wordlessly holds out a hand to the interpreter.

She lends him her lighter with a look of disgust on her face. He doesn’t notice and just lights up. She takes her lighter back and leaves. The cigarette tastes awful, but to him it works its way into his psyche as something much more than simple used papers and old tobacco, the same way the taste of the ones given to him before when someone took pity on a man they saw as a dead man walking lingers on his tongue even months or years later. The gesture transcends language and culture. Not quite sorrow, not quite regret. He finishes the cigarette and then shifts around in the ashtray a little more until he realises there’s not much more to be had. He wipes his hands on his trousers.

Some time later they return and take him back into the workroom, arms over their shoulders in a casualty carry. The floor is damp but clean. His blood- his own name traced in it with a shaking finger- is gone. There are several black bin bags scattered around a blue plastic chair. He sits down on it, and it cracks beneath him. He doesn’t weigh much- not now, the fat and muscle dropped from him- so he looks at the chair and thinks it might just break beneath the slightest shift in weight.

They tell him to undress, and slowly, he does. His clothes go into an orange biohazard bag. It is sealed up and they try to get him to stand in the corner. He takes his eyes off the bag for a moment as he sits on the floor, and then crumples onto his side, watching them take the bag from the room with his cheek pressed to the cool tiles once again. He is not sure what becomes of the bag, but lies naked on the tiles and doesn’t think about it. A Special leans over him and holds out a hand. “Glasses,” she demands.

He sits unmoving for a moment before his brain starts to work. “Glasses,” Fennec repeats with numb lips, and then slowly takes them off and hands them over to her, propping himself up with an arm that aches like it is broken. He lies back down on the tiles again, staring into space through the blur.

He hears the noise of the water running through the pipes before he hears the hose hissing. It's just like the times they have hosed him down before. It hits him with a tangible force and it hurts. It hurts anew, and it makes old wounds hurt once more. The water is freezing. He can’t quite comprehend how cold it is- just that the cold is what makes it hurt so badly. He opens his mouth with a silent gasp, eyes widening, but still doesn’t move.

Then they rustle in the plastic bags over the other side of the room a little more. Out come two bottles of soap. They pour it onto their gloved hands and start to wash him down with it. It stains his skin an off-yellow before it foams up. Fennec freezes up as they scrub at his neck and head and stays frozen for anything less impersonal than his arms or legs. He doesn’t like it one bit and they are not gentle. “Look at this,” says the man rubbing knuckles against his scalp. The man tries to pull fingers through his hair and is stopped by the web of knots and mats that it has become.

The woman isn’t interested. “Just shave it off. Don’t have time for this shit.” Fennec doesn’t understand until, over his head, one Special presses a pair of hair clippers into the hand of the other. The clippers go on, buzzing, and he flinches, bringing his hands up to cover his face. Chunks of soapy matted hair fall to the floor, and he squints through the blur around him as they take the clippers to his beard. A gloved hand under his chin tips his head up, his mouth twisting into an expression of resigned fear as the first matted pieces fall from his face. When there is no more to shave, they rinse him down again with the hose. It’s so cold he finds that the tears that reflexively pour down his cheeks are the warmest part of him, and he curls up with his knees as close to his chest as he can get them.

One of the Specials takes him under the arms and pulls him a little way backwards, sitting him against the wall on the dry part of the floor. He starts to shiver. Watery blood runs from the stitches on his leg. His lazy eye drifts off to the left, looking at nothing in particular. They dry him off with a towel so rough it reopens wounds he forgot he had. He puts his hands back over his face and lets them do it. They do not give him his glasses back, even as he looks around for them, blinking slowly. He puts his arms through the T-shirt they hold out to him and they pull it over his head. One of them holds him by the elbow so he can balance to put on the underwear. They have to help him put the white socks on. They don’t give him shoes.

The taller of the two men holds up a dark green set of scrubs to him, a large fluorescent orange star on the back of the top, smaller ones on the right side of the trousers and the right breast of the top. Fennec stares at them blankly. It doesn’t really occur to him to put them on or make any move to do so. Another moment passes, and they just grab him by the shoulders and pull it over his head, and then put his arms through the sleeves. He looks from left to right as they pull the trousers up on him, confusion written all over his face, brow furrowed. They tie the trousers at the waist with the tattered drawstring. It all smells of disinfectant. He smells of iodine soap- skin, hair, he can even taste it in his mouth.

The woman who took his glasses pulls a woollen mitten over one of his hands. He offers up the other, stretching out his fingers under the mittens, staring at his hands as they bring out the duct tape to tape the mittens in place. He sits there unmoving as they smooth the end of the tape down to his skin. The duct tape is wrapped around his wrists several times, sticking woollen gloves and already-fragile skin together tightly. He looks at the breeze blocks in front of him and wonders where exactly his life went to shit as they cuff his hands together over the top of the mittens. It takes two of them to stand him up and hold him up- although he tries to take his own weight, his legs tremble violently- and they wrap another chain around his waist, to attach his hands to it. Midway through that, someone slips a blindfold over his head- an elasticated sleep mask. He can’t help but notice the little improvisations made- clearly tried and tested and deemed more than good enough. On the first attempt, it falls from his face and ends up loose around his neck- the second try, they knot the elastic of it at the side of his head, over his temple- and it stays put.

“I can’t see,” he says, almost a reflex. Nobody understands him- and he is almost relieved when it dawns on him what a stupid thing that is to say. He tuts quietly. A moment later, he’s sat back down, the hands now pressing him back down against the back of the chair as he feels the ankle cuffs go on- biting the skin above his socks.

Someone touches his face. He panics, crying out. They touch his face again, just above his ear and he shakes his head, pulling away with stuttered protests, not really understanding what’s going on, until someone slaps him across the face. He stops moving again. They put a surgical mask on him, the metal pinched over the bridge of his nose and the elastic looped over his ears- and slowly it dawns on him- it’s so he doesn’t spit at the people around him, or try to use his teeth to pull the mittens from his hands. His cheek burns. He feels so, so exposed. Cold, blind, defenceless, he crawls back inside himself.

Any other time he might wish he were dead. Now he worries that he will be soon- and he worries how much it will hurt. So he sits there and he hopes it won’t hurt too much, and it won’t take too long. Death, he thinks, is too broad of a word. He wishes for quick and painless.

He remembers seeing a film when he was in his late teens- far too violent for a child like him, but at the same time, he was enraptured by the cinematography. The film ended in a peculiar manner- the main character, reaching across the villain’s desk to shake his hand- the two face-to-face, in profile, over a vast expanse of white and grey and mahogany- and then a cut to black so abrupt that for a moment before the lights came up he thought the projector had blown- not an uncommon occurrence- but no. The film was over.

As the credits scrolled, everyone in the theatre knew the character was dead- he could not piece together what made them all so sure. Maybe the film had just ended there- maybe that was just the start of another arc of the story, the beginning of the antagonist being brought to justice. But he knew the main character was dead. He couldn’t work out how he was so sure until he asked one of his friends who worked in the theatre to show him the reels.

Thirteen frames before the cut to black- a little over half a second of film- the protagonist’s head jerking forwards as if hit from behind- abrupt white, abrupt bright crimson red, then the cut to black. Too fast for the eye to process- but his brain knew and pieced together the frames a few moments after it happened. And then he knew for sure the film was made by artists, a labour of love and skill. Thirteen frames, too fast for the eye to see- solidified the idea of unseen art.

He supposes death, when it comes, will be much like that, but there will be no moments after for his brain to catch up with what has happened. He discards the train of thought after that, and just sits there, feeling the heaviness in all his limbs. A distant argument he doesn’t understand drifts into earshot, and then footsteps, and then someone tugs the blindfold from his eyes. “Check his pupils if you think I've turned him into a vegetable, then,” says the butcher- Fennec doesn’t quite follow any of his words, but the smell of the man’s breath- chewing tobacco and rotting meat- is unmistakable. The face of the medic swims into view. Fennec watches the finger of his hand as he holds it up, moving it across his field of vision, and then the medic pulls out his penlight.

Fennec scrunches his face up with a tut as the man turns his penlight on. The medic waves the light over one eye, then the other. Fennec’s pupils constrict and his face twitches. He pulls a face of discomfort as his eyes start to water. “Reactive to light,” says the medic, and pulls the blindfold back down. “Neurologically intact.”

“Intact but he ain’t moving,” says the butcher. “Nothing I did to him. It’s psychiatric. Sign off on him, don’t dick me around.” Still Fennec doesn’t understand much of what is said, but what he does grasp, isn’t particularly flattering in his direction.

“Fine.” The faceless man tuts- Fennec can’t see him, but recognises the voice, even in English. "I'll sign the detainee's transfer papers, then."

Fennec hears the butcher spit on the floor, and startles as the light blow of the butcher clamping a hand on his shoulder lands on tender skin. The hand stays there as someone fits the ear defenders to his head over bristly, still-damp hair, and then withdraws. He can hear nothing but a low mumble of conversation, and his own laboured breathing. They pick him up from the chair with hands under his armpits- his feet scrabble for purchase, his knee burning- but they lift him from the floor, and his legs simply drag along the concrete for a few moments, until more unseen hands pick them up.

For a moment it is as if he is weightless once more- and then it ends as his back meets metal plate flooring with a bang. Ears ringing, the non-slip pattern digs into his back and he lies there, unmoving and winded.

The ringing in his ears slowly fades away but the pain in his ribs remains. Someone sits him up- hands under his arms again, twisting him a little, pushing him back against something metal- sharp edges digging into his back- and a tug at his wrists tells him they are securing him to it. Another tug at one ankle, then at the last, secured to the floor like any other piece of cargo.

Footsteps move back and forwards in front of him. They're going somewhere, he realises, and the terror makes his heart tremble in his chest. An ignition starts, an engine rumbles through the metal floor beneath him. He cannot hear it, only feel it. He still can’t find it in himself to really move, he turns his head to one side, and it sticks there until he lets it drop.

The world jerks forwards as they move off. Fennec wishes for his thirteen frames between being and unbeing, and he wishes for that to be all there will be waiting for him now. He knows there will be far more. Life, he thinks, isn’t fair- and he thinks, it’s not art either. It just hurts. His face crumples but there are no tears and there is no sound. He dare not.

#implied torture#yeah the ashtray thing is gross i know#someone buy him a vape or something idk#mouth gore#just to be safe#sorry my guy#there is worse to come

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Find yourself shaking, carpet imprinted in your palms, the taste of someone else in your mouth. Blood drips from a nosebleed you aren't quite sure of the beginning of. Tears. Headache and aching throat, the sound of someone doing up their trousers and their belt- metal on metal- and you have to wonder- how did I end up here? Have I hit rock bottom again?

No. No, there's plenty more to lose, you must tell yourself this, and you should wipe your mouth. Do you feel good about yourself?

- From the diary of Anton Fennec

#implied noncon#this scene is proving a bitch to write so the art is to compensate#sorry fennec#cw suicide#cw noncon#cw dubcon

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Defector Takes The Stand // Anton Fennec

Today in the historic trial of seven German Navy officers accused of violating the laws of war and causing the deaths of eleven State prisoners of war, the key witness for the prosecution speaks for the first time. Anton Ellmenreich von Fennec was the senior officer on board the Horatio and formally defected to the State in June before facing trial and being found guilty of three charges of negligent manslaughter and one of cowardice & desertion in July. Brought in under armed guard and sat behind a layer of bulletproof glass amidst fears for his safety, Mr von Fennec appeared in uniform and spoke so quietly that at several points, the questioning was stopped briefly to adjust the microphone as he was inaudible to the interpreter. The initial questions revolved mostly around his fitness to testify following a recent suicide attempt, which Mr von Fennec very plainly denied affected his comprehension or recollection of the events on board the Horatio. Once the defence's objection to the witness was settled, the testimony began. The initial cross-examination went on for three hours after which an adjournment was called to allow for a relief interpreter to be brought in. He presented a unique perspective to the court which has as of yet not been heard- of a ship far out of control and a crew caught in the grip of hysteria, with a captain who lacked the skill or ability to bring them back in line, creating the perfect storm which had tragic consequences for eleven of England's finest men and women. The trial continues tomorrow with further cross-examination of Mr von Fennec.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Really Did Try // Anton Fennec

He winces as he sees his own face. The remains of a nosebleed are clotted in his beard. The whites of his eyes are a sort of pallid pink where blood vessels have burst. His neck is a sorry mess- angry black bruises and thin red lines of rope burn- and claw marks, he realises. The half-moons of his nails are raked into his jaw. He looks at himself in the mirror, staring into his own bloodshot eyes, feeling his broken fingers throb from where he'd clawed desperately at his own throat to try to free himself, and wishes he’d done a better job of it all. When he speaks he doesn't sound like himself. He can taste blood still- he must have been chewing on his tongue for quite some time. He doesn't remember. "Are they still expecting me to testify?" he croaks. He knows the answer without asking. He is still alive. They will make sure he testifies, even if it is the last thing he does. He hopes the others know he tried. He really did try. But there are no more options. He will testify against them and he knows, deep down he knows, he will send them all to their graves with it. And, he hopes, he really hopes- he hopes he'll be joining them.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

If I Feel Something, My Body Betrayed Me

A Verschlimmbessern AU. Instead of defecting, Fennec is returned to his home country in a prisoner exchange. Contains depictions of suicide and self-harm, death references, brief mentions of rape, and themes of mental illness. The title is from this song.

---

They brought him to the border at Dover with a black bag over his head and his hands zip-tied in front of him. He didn’t really mind, at that point, he just fell asleep in the back of the car. The bulletproofing muffled the road noise. All he could really hear was his own tinnitus- that was new, and had started after he had been held underwater for a little too long. He was sure there was no more water in his ear but the ringing remained stubbornly.

It was a quiet affair, not much to it. This had been repeated hundreds of times- the absolute extreme of diplomacy the Eurocorps would engage in with the State of London City were wordless prisoner exchanges- so it ran like a well-oiled machine. Both sides set their prisoners loose at the same time. There was a pause as they cut Fennec loose from the zip tie, and he saw that the Eurocorps had brought the Englishman without even handcuffs- but he supposed they must still think he was going to run. He started to walk towards the border, not slow, but not fast either. He had no intention of prolonging it.

He’d thought about running but there was nowhere to run to anymore. All that would do would get everyone here killed, and quite possibly start a hot war- not the cold one the two countries sat in at present. He had no intention of being shot and bleeding to death on the tarmac here. It was, and he knew now, not nearly as peaceful as they made out it was in books. If you weren’t lucky enough to die immediately then you were going to suffer.

On the other hand, there was no need to restrain the Englishman. He was going home. He passed the Englishman- the man’s family waiting in a Department of State Affairs car a little way behind the border for him.

Fennec wished he was going home, but he knew he wasn’t. The federal police were waiting for him, and he could see them, and yet he kept walking- limping- towards them. He crossed into French territory and didn’t feel any different. They were waiting for him just over the border. The hand on his arm surprised him how quick it was- he was expecting to have to walk a little further.

It’s over, he thought. It’s all over.

“Anton Von Fennec?” asked the policeman.

He nodded slowly, looking between the three of them there. “How long were you waiting here?” was the only thing he could think to ask. Five hours, they said. Fennec looked at the warrant they showed him, shrugged, and just walked with them to the back of the car in silence. They didn’t put him in handcuffs. There was no need.

They travelled back in silence as well. The pressure in the plane gave Fennec a headache and made the pins in his leg ache, and so he sat pitched forwards in his seat, head in his hands. The officers on either side of him kept a quiet eye on him but said nothing. There was nothing to say.

---

He cooperated with the interrogations, and gave them everything he knew. In return they allowed Alais to come and see him- and whilst Alais spoke to him, they looked after Sabine, not much more than a toddler, laughing and pointing at things that took her interest. The rural police who had brought Alais down were delighted. The federal police who had taken Fennec into custody were not so delighted.

Alais was offered the option to have one of the officers sit in with them. She turned the offer down and just walked in without any sort of prelude. Staring at his wife over the top of a cup of weak tea, Fennec thought he was hallucinating again- until she opened her mouth. “You’re an idiot,” she said. “What the fuck were you thinking?”

Not hallucinating, then, he realised. He held up a finger to her, motioning for her to sit down, took a sip of his tea and put the cup back down. “How much do you know?” he asks.

“You’re an idiot, Ant,” she repeated, sitting down.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I was afraid. I didn’t want to drag you into this, you know?” he said, looking up at her, and then his face cracked into grief, and he had to hide his head in his hands to stifle the sobs. “I’m sorry,” he sobbed. “I didn’t want to drag you into this.”

She waited patiently for him to pull himself together before she told him that they were going to get through this, together, at which point Fennec promptly dissolved like sugar. She leant over the table and put a hand on his- glancing at the two-way mirror, not sure if she was even allowed to touch him- and gave his arm a little squeeze.

---

The hearings started the moment they could find the people to hear them. He was not a flight risk, having nowhere to run anymore, but the magistrate drew up a pretrial detention order all the same, citing the exceptional gravity of the case. The defence lawyer- an old man who seemed to walk with the weight of the world on his shoulders- asked Fennec if he would like to appeal. He shook his head, making some weak excuse about time and effort or something or other.

The lawyer saw right through him. “You don’t want to go home, do you?”

Fennec burst into tears right there and then, shaking his head. They didn’t appeal the detention order.

He didn’t, as he thought he might, cry when they took him to the detention centre- instead he found himself drenched in a cold sweat the moment the building came into sight. A rather unappetising shade of grey, with windows set behind metal grilles, and the bright burn of fluorescent lights behind them.

It remained a quiet affair, unremarkable for what it represented. The locked gates behind him, between him and the outside world made him a little uneasy. They showed him around the places he would be allowed to go, and then went through the rules- handed to him in a ring-bound booklet, laid out point by point.

Fennec swore to Alais he was taking it well, but seemed like he was wasting away. He lost weight, a nervous demeanour clinging to him at all times that meant he ate very little, smoked too much, and paced whenever the pain would let him. Expecting to be beaten, his pulse would quicken with his heart pounding against his chest each time his name was called for something- but the blows never landed, and were never thrown anywhere except for in his mind.

---

For a few weeks, there were talks of sending him to the Hague. In the end that never materialised- the examining judge looked at the evidence, at the interrogation records, the testimonies of the people on the boat that had made it home- and decided there was not really much basis to convict him of a war crime on. Charges of treason were similarly drawn up, and thrown out on the basis that again, there really was no indication that Fennec had meant anything to come of all the bad decisions he had made, and the penal code states that unless there is a specific charge for negligently committing a crime, nothing will stand without intent behind it.

The six charges- five for the State soldiers who had died on the barge, one for Atticus, whom he had killed- all started out as murder without aggravating circumstances- Totschlag- but the more evidence that was brought up, the less culpable Fennec became in the eyes of the court. The soldiers from the Horatio, and even the remaining officers all said the same things- painting Fennec as incompetent, oblivious and negligent, but not a murderer. The blame ended up mostly on the dead- Christoph Fride and Atticus Raines. The forensic evidence from the dead soldiers agreed- blame the dead.

The question of what had led up to Atticus’ death came up and lingered for several days. Fennec had confessed to what had happened in as much detail as he remembered it. The forensics didn’t exonerate him- the bullet that was dug out of Atticus’ body belonged to his sidearm, but, again, the survivors came to his defence. Several of the soldiers testified that Atticus had begged to be killed- and Fennec sat on the defendant’s bench and wondered why they would exonerate him in such a way when they could have simply left him to rot.

They ran through each of the cases of the dead soldiers- finding duty records from god-knows-where, proving where Fennec was at the time each of the soldiers died or was killed, and found that in three of the five cases, he had been asleep at the time, and that Fride had been the one at fault. Those charges were dropped. Still Fennec couldn’t fathom why they would go to such lengths for him. He didn’t understand it.

In the end the case was brought for two counts of negligent killing, and one of killing upon request. Negligent killing demanded a prison sentence of up to five years, killing upon request from six months to five years. The prosecutor and the defence lawyer talked for a very long time, and in the end, came to an agreement of nine years- two and a half for each of the counts of negligence, and four for the other charge.

---

Fennec was taken back to prison and there he languished. There wasn’t really a better word for it.

He started paintings and then never finished them. He cleaned what he was asked to clean, dusting and vacuuming his cell, and went where he was asked to go, did what he was asked to do. Let someone else do the thinking for him. He resented the psychologist’s attempts to make him think about things that seemed too enormous to understand in their fortnightly half-hour meetings- in his mind, it was simple. He was there because he was to be made accountable for his own guilt. The crime led to guilt, which led to the penalty, as simple as dominoes.

Alais visited once a month- the journey up was long and Sabine needed someone at home. One day she would be old enough to come too, but Fennec maintained she was not to see him in prison, not to come and visit.

“You don’t want to see your daughter?” asked Alais.

“I want to see her very much. I don’t want her to see me,” said Fennec. “Children should not be exposed to such things.”

Alais just stared at him until he elaborated. It took a few moments, Fennec missing the non-verbal cue for a long beat. Eventually it clicked. “I don’t want her to think this is something to aspire to, or something normal.” He scratched at the back of his head. “She needs to be old enough to understand why I’m here. Right now, she is not.”

At last Alais understood his insistence. The next week, in the mail, came a little pink bear from Sabine’s bed. The letter said, in Alais’ unrestrained cursive, that she had picked it out for her father. Fennec thought about sending it back on principle, but relented. He set it on the shelving above his desk, watching him. He fell asleep looking at it and dreamed of his daughter.

He woke up in tears, putting a hand to his face and finding it damp. With a groan of pain, he sat up in bed, put both feet on the floor and staggered over to the desk. He turned the bear around to face the wall, and then limped back over to his bed, hauling his bad leg onto the mattress with a hand beneath it.

Each time they searched the cells- which they did with some regularity, but not too often- he watched them go through his paintings, on thick paper with their edges warped with water from the watercolours, and wondered what they thought of them.

“What is this?” she said, holding up the pink bear.

“It is from my daughter,” he said.

They took the stuffing out of the bear onto his desk. Fennec looked at the bear and the bear’s white insides strewn all over the light wood desk, and thought that him and the bear must not look too dissimilar. Satisfied, they moved on to searching him, a simple frisk down his body, turning out his pockets. There was no reason to think he was harbouring anything. He winced as they felt down his left leg, but never said anything. He put the stuffing back in the bear and put it back on the shelf.

---

A few weeks passed and he found himself exhausted. He wasn’t sleeping and he didn’t know why. He couldn’t draw and he didn’t know why. He sat up late one night trying to finish a drawing- trees casting a shadow over leaves- and nothing looked right. Nothing he put on paper looked right. A few more lines and the drawing looked worse. Nothing looked or felt right but he couldn’t for the life of him put a finger on why. He went to sharpen his pencil and the pencil snapped.

He picked up another pencil, trembling with frustration. He put the pencil into the pencil sharpener and slowly twisted. The pencil sharpener unceremoniously broke in two. The blade came loose from the yellow plastic and bounced across the table. He cried a few quiet tears of frustration over it, and then when the tears cleared from his eyes enough that he could see what he was doing, his gaze fell on the blade from the pencil sharpener, lying on his desk. He stared at it for a few moments, the idea half-forming in his head.

He picked it up and held it for a moment, before the idea took hold of him entirely. He raked the blade down both arms. The blood welled up almost immediately, spilling down onto his trousers and shirt. He went back to bed with the intention of not waking up in the morning, fluffing the pillows even as he smeared blood over them, rolling onto his side to get comfortable as he bled through the sheets and into the mattress. Later on, he couldn’t quite explain what had come over him. Nothing more succinct than he was tired, and he wanted to go to sleep, and it seemed like the quickest way to do it.

They found him on his bed, bleeding wrists clutched to his chest, half-asleep. The remains of the pencil sharpener were snapped underfoot. The guards couldn’t rouse him, and thinking he was dead, tried to drag him onto the floor to start CPR, until one of them pressed down on the muscle between his neck and collarbone, and his eyes flew open with a startled cry.

---

He spent the next few days curled up on a bed in the infirmary. The psychotherapist thought that it amounted to guilt and guilt alone. He refused to speak to the psychotherapist, sitting in silence until the clock ran down.

He wouldn’t speak to the psychiatrist either. They sat looking at each other in silence, the psychiatrist looking through Fennec’s records, including the sheets translated from English that described Fennec’s episodes of mania where he had neglected to sleep or eat, obsessed with the thought that the pigeons outside were sent from Germany to spy on him, and accused anyone and everyone around him of trying to poison him.

Every sort of food or drink they brought him, they had somehow poisoned- there were several pages of incident reports full of the bizarre logic of psychosis, ranging from the mundane of slipping poison into the drink when he wasn’t looking, to poisoning the cows the meat came from using an undetectable poison designed to be hidden on blood work. He itched himself raw on his arms in his stress and blamed it on the poison. He was moved into a room with no windows to see if that would help, and swore he could hear the birds in the walls.

Eventually, convinced he was being poisoned by one side and spied on by the other, a terrified Fennec had tried desperately to smash a window to throw himself out of. That was enough for the State’s psychiatrists to act decisively. Brought on by antidepressants, they had put a stop to it with a course of high-dose thorazine and electroconvulsive therapy.

The psychiatrist asked Fennec about the birds. “Do they still follow you?”

Fennec looked up, the first time he had since he sat down. He just shook his head, almost imperceptibly. The psychiatrist eventually gave up and wrote a repeat prescription for antidepressants and lithium, not knowing what else to do with the silent man in front of him.

---

Fennec returned to languishing. He had to pay from his accounts- a mix of earnings and what Alais had paid in for him- for the new mattress. The old one was unsalvageable and sent off to be burnt. The gashes up his arms needed to be glued back together. He didn’t read any of the letters Alais sent, and for several weeks didn’t send one back, until she showed up, and he felt too guilty not to sit down with her and explain what had happened.

She took it surprisingly well. “That wasn’t a good idea, was it?”

He shrugged, leaning on the table with all his weight. “No.”