Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Bibliography

Books

Kossak, S. (1997), Indian Court Painting, 16th–19th Century, MetPublications

Said,E.W. (2003), Orientalism, London: Penguin.

Bhabha, H.K. (1994/2004), The Location of Culture, London: Routledge.

Strong, Roy. (1999), The cult of Elizabeth: Elizabethan portraiture and pageantry, London : Pimlico

Hendley, TH. (1883), Memorials of the Jeypore Exhibition 1883: Razm Namah or History of War, London: W.H.Griggs

McInerney, T. (2016), Divine Pleasures: Painting from India’s Rajput Courts – The Kronos Collections, MetPublications

Journals

Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, (1917). ‘The Opening of the Albert Hall and Museum at Jeypore’, Vol. 65, No. 3351, p. 228-229

Behrendt, K. (2000). ‘Poetic Allusions in the Rajput and Pahari Painting of India’. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sardar, M. ‘The Art of the Mughals after 1600’. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Websites

'Young Man Among Roses' by Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619) [online] Available at. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/y/nicholas-hilliards-young-man-among-roses/ [Accessed 30 Jan. 2019].

Raja Man Singh portrait [online] Available at. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O433303/raja-man-singh-painting-unknown/ [Accessed 5 Jan. 2019].

SIROHI: Umed Singh, Maharao of Sirohi (ruled 1862-1875) [online] Available at. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/photocoll/s/019pho000000127u00052000.html [Accessed 5 Jan. 2019].

Maharana Ari Singh with His Courtiers Being Entertained at the Jagniwas Water Palace [online] Available at. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1994.116/ [Accessed 15 Jan. 2019].

The Art of the Mughals after 1600 [online] Available at. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mugh_2/hd_mugh_2.htm [Accessed 15 Apr. 2019].

A History of the Portrait Miniature [online] Available at. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/a-history-of-the-portrait-miniature/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2019].

Miniature Painting [online] Available at. https://www.culturalindia.net/indian-art/paintings/miniature.html [Accessed 10 Feb. 2019].

The art of realism Painted photographs from India [online] Available at. https://iias.asia/sites/default/files/IIAS_NL51_1617.pdf [Accessed 10 Feb. 2019].

"Shah Jahan on Horseback", Folio from the Shah Jahan Album [online] Available at. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/55.121.10.21/ [Accessed 10 Feb. 2019].

The Indian Portrait - VIII: Paintings from the Royal courts of Rajasthan [online] Available at. https://www.academia.edu/33604295/ The_Indian_Portrait_-_VIII_Paintings_from_the_Royal_courts_of_Rajasthan - The Indian Portrait - VIII: Paintings from the Royal courts of Rajasthan [Access 18 Apr. 2019].

1 note

·

View note

Text

Reflection on Podcast

It has been a fantastic journey getting to this stage and this review will allow me to reminisce and unfold on the entire process. I began with many different channels of research available to me. At first this was daunting and I worried I would spread my research too thin and not delve deep enough into the Orientalist ideas that I was hoping to. Upon finishing my podcast, while I still feel I covered a significant amount of different content, it all complemented each other to my relief. For example, I was pleasantly surprised when I grew to understand the connection between the Orientalist intentions behind the book, and how this transferred physically. A demonstration of this is the oval shaped frames, which are symbiotically representative of Dr Hendley’s documentation intentions and of a classical style of Elizabethan portraiture. Thus I was able to bridge the different areas of my research and develop a knowledge of how Orientalism presents itself both physically and in less overt ways.

I was also pleased with the comparisons I drew between the book and the miniatures. As these were not as drastic as I had thought they would be when I first undertook the project, I decided to go even further back in response to this. Looking at original miniatures of the Maharajas allowed me to draw a greater number of comparisons which gave the demonstration of the alteration process more gravitas. I also found that these could be complemented well by the imagery in the video - something I had struggled with in context heavy sections of the podcast.

When I initially chose Dr Hendley’s miniature paintings I could never have dreamed they would lead me to the deep understand of the impact of colonialism on the art of Rajasthani chiefs. The questions which arose along the way were gems of surprises which kept me intrigued until the end. My favourite uncovered secret was the impact of photography on the book. As portraiture, especially in Dr Hendley’s view, was supposed to be representative, it is understandable that he would use photography whenever available. The arrangement of the faces with the eldest and most contemporary rulers juxtaposed in close proximity highlighted the contradictory nature of the photographs, compared to the beautiful symbolic miniatures around them.

In the end I used the high res images that Rachel had sent me for a lot of my podcast. They were much more clear and sharp. Although this was not something I had anticipated, I was glad with the final product. As the miniatures are so detailed and small, it was imperative that people were able to view the finer details on the hairs and jewellery. One problem I found when filming my podcast was the difficulty in obtaining video footage of something so 2D and flat. I attempted to swerve this problem by using a stand, which worked somewhat. I was happy with the eventual photography that went into my video for the most part. One thing I would do differently if I could would be to take better photos when I went to the V&A to see the original as these could have been included in my podcast. At the time I had no idea that so much of my podcast would focus on the pages of the book.

Overall I had a wonderful time making the podcast. I’m sure my love of miniatures will never leave me and I am grateful for the understanding I have gained through my research. I was particularly thrilled to learn more about Dr Hendley. In Jaipur his presence was evident in the Albert Hall Museum, a gallery I was thoroughly impressed by not only because of the splendour of the colonialist building but also because of the collection of paintings. On first reading of Dr Hendley it was hard to fault him. He was devoted to the arts and clearly had a passionate relationship with India. I was however grateful that further research, including of Said’s Orientalism allowed me to unpick the innocence of the relationship. Through the book’s tones and undertones I uncovered what must be held in the minds of its observers and I hope I managed to convey this in the podcast.

I hope you enjoyed watching it!

0 notes

Text

Final Podcast Script

These miniature paintings were commissioned by Dr Thomas Holbein Hendley for the creation of his book “The Rulers of India and the Chiefs of Rajputana, 1550 to 1897”. The name Rajputana identifies the area of the Indian subcontinent that is now Rajasthan, and areas of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and southern Pakistan. Rajasthan, directly translates to ‘Land of Kings’ [NU1] and it is these kings which are the subjects of the miniature paintings in the Oriental Museum’s collection. The museum’s collection is made up mostly of the Chiefs from Jaipur and Bikaner whose reins range from 1468 to 1897.

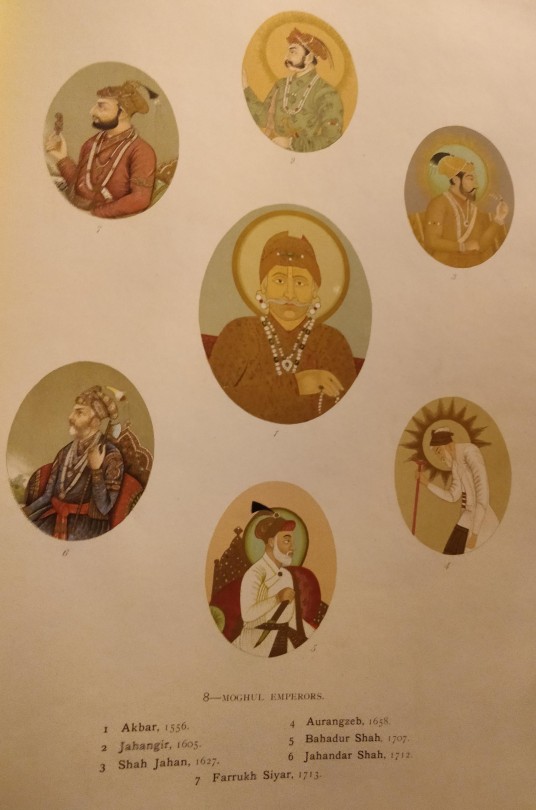

From 1526 India was largely ruled by the Islamic Mughals and so the book includes portraits of the Mughal emperors including Akbar The Great and Shah Jahan. Dr. Hendley’s rationale for this was to begin his ‘history’ from the point when the British first began to intervene in India. Indeed, a drawing of Elizabeth 1st takes pride of place at the very start of the book. The ‘history’ that Dr. Hendley describes, therefore, is a history that was enacted under the ever-watchful eye of British Imperialism. As such, his book we may argue, was conceived and written from a colonial perspective being concerned solely with the history of Rajputana since the British first intervened in the region.

The collection contains 30 miniature paintings, all of a similar small size and oval shape, sharing the same decorative style and side profile depiction of their subjects. Many questions arise from these miniatures. What sources were they recorded from and with what intention? Is their purpose solely for documentation and if so, what impact does this have on their role as art?

Creating this encyclopaedic book, collating information and commissioning reproductions of portraits of the rulers was a laborious process. Hendly wrote ‘The collections of the Princes have been carefully studied, and in some cases (especially in that of the Emperors) very many portraits have been examined and the best chosen for reproduction’.

Dr Hendley’s purpose in publishing the book was to act as an historically accurate record of over 300 years of Rulers at the time of increasing intervention on the part of the British. In the book Dr Hendley describes the challenge of trying to obtain reliable portraits. He writes ‘it must be remembered that very few native artists are capable of taking a portrait in full face.’ Here he reveals a typical colonial point of view regarding India and its art forms. He suggests that Indian artists are qualitatively inferior to European artists because of their supposed inability to practise Western forms of representation. Dr. Hendley’s comment represent an excellent example of what Edward Said calls ‘Orientalism’, a nexus of views articulated by Western European countries in the 18th & 19th centuries regarding the ‘Orient’ in which the ‘Orient’ was considered to be inferior to the West and hence in need of its corrective intervention. Dr. Hendley does not stop to consider the possibility that these artists might have engaged in different forms of representation as a result of indigenous aesthetic systems. He concludes that ‘On the whole it may be safely asserted that the most characteristic and reliable representations of the notable men… have been selected.’

It was typical of Indian miniature portraiture to use symbolism and exaggeration rather than western ideas of realistic representation to portray the individual. The side profile view, for example, is typical of miniature paintings from the Indian Subcontinent along with other stylistic features such as big eyes, often with a red rim or heavily hooded eyelids.

However, the way features were depicted changed with the reign of Akbar the Great with actual like-nesses becoming immensely popular’. This painting of the emperor Shah Jahan painted in 1630 has attempted to capture a likeness - the details on the face are more realistically represented. The eyes are smaller and less stylised.

Even though Dr Hendley was determined to create an historically ‘accurate’ representation of the kings of the Rajputana in Western style, the miniatures in the collection represent an excellent example of what Homi Bhabha calls ‘hybridity’, a complex mix of British and Indian cultural forms.

The book also displays hybridity by placing portraits which are loyal to classic miniature paintings alongside much more modern reproductions. With the advent of photography Hendley was able to create or access realistic, full-frontal portraits of the Chiefs. This cultural and temporal interchange becomes visible by observing this page documenting the Chiefs of Jaisalmer. The sequence ends in the centre where the first and last ruler are deliberately positioned facing each other. When observed through an orientalist lense, this abandonment of traditional miniature portraiture for a more ‘realistic’ alternative whenever available, conforms to Sied’s ‘corrective intervention’ idea.

By drawing a comparison between the portraits of Maharaja Mansingh from the collection, the book and other sources, the cultural exchange is highlighted. The main difference is the much more ornate decoration adoring the king in the later recreations. The original presents a standing Maharaja with his whole body included in the composition, as was typical of miniature portraiture from the Indian subcontinent in the 1600-1800s. It was most common for the subject to be represented as standing, reclining or on horseback. The inclusion of weapons or equestrian imagery display prowess in battle and so was a common feature in miniature paintings for these feuding kings. In contrast, only the bust of the subject is included.

This bust is placed in an oval frame, a distinctively European influence. It was typical from the Elizabethan court through to Queen Victoria’s to have your portrait painted in miniature and placed in an oval frame with a gold rim. This exact process has been mirrored in the miniatures in the museum.

This miniature of Maharaja Sardar Singh of Bikaner is fascinating. The king is clutching a shield and his turban is adorned with numerous items. The alteration process undertaken is most obvious in the background colour, which changes from the vibrant Rajasthani green to a more subdued brown. Apart from this alteration, the facial features remain the same. The portrait of Mansingh also undergoes a significant change. The nimbus, meaning a circle of light similar to a halo, indicates royal status. The nimbus has evolved from a typical green and gold colour to white. Green and gold both symbolise regality in Rajasthan and this transformation to white is much more reminiscent of European royal symbolism such as Elizabeth’s white lace collars. However, the feature of a halo to represent imperial power is a symbol borrowed from European art, so the hybridity is circular.

Cultural interchange in miniature painting did not originate with the British influence. Hindu and Muslim styles of miniature painting evolved independently for a time, creating distinctive and original creations which over time began to interact. Starting in 1526, marriage alliances between Rajasthani kingdoms once they had become subjects of the Mughal emperors became more frequent. As it was traditionally women who commissioned paintings, the influx of Rajasthani nobelwomen into the Mughal royal family played a pivotal role in cultural exchange. [NU2] This fresco from Chitrashala in Bundi shows lingering remains of the Mughal style amongst the Rajput traditions. The delicate, detailed court scenes are an influence of Mughal Art, as are the decorate borders. Colonialist influence is subtly unveiled through the scenes of hunting which were a British activity adopted in amongst the Indian nobility.

In comparison to the Mughal control, the foreign colonialism from the mid19th century was came with orientalist repercussions. Dr Hendley’s book is an example of this. Dr Hendley first travelled to India in 1869 and established the Albert hall museum in Jaipur. A sign outside reads the ‘Albert Hall became a centre for imparting knowledge of history of civilisations’. Despite his unwavering dedication to the promotion of the arts, and loyalty to the traditions of Indian miniature painting, Dr Hendley’s Orientalist bias is resonant. The function served by the book, primarily to document the Orient for foreign eyes, cannot be detached from the miniatures themselves. The art was created to serve this colonialist purpose and this permeates its very fibre from the oval frames to their final destination on the pages.

0 notes

Photo

A selection of photographs from filming day! I was glad to have a plan of my podcast before going. I was also glad to have a copy of the book, if only a replica, to demonstrate my points.

1 note

·

View note

Text

18/04/19

https://www.academia.edu/33604295/The_Indian_Portrait_-_VIII_Paintings_from_the_Royal_courts_of_Rajasthan - The Indian Portrait - VIII: Paintings from the Royal courts of Rajasthan

Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II

(1834, r.1835-1880)

of Jaipur

by Jaipur court artistcirca 1860 CE

Influence of visiting European painters and introduction of camera had a lasting impact on art practice of local artists in his reign and they adopted photo-realism, naturalism, and techniques like oil paint and watercolour. Reference for majority of his portraits can be found in his self-taken photographs.

Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II is depicted here in his signature imperial moustache, split beard and spectacles. A pair of spectacles are placed on the round table along with a vase from which he has taken a rose to decorate in his turban. Folded velvet curtain in background draws European drapery style. Fine detailing of the texture of his combined (western and Indian) clothing allows one to distinguish different textiles like velvet overcoat with brocade, silk waist cloth, cotton trousers and leather boots.

This could be interesting to bring in as not all the portraits are the same style as they span 300 years. So the later ones tend to be more European influenced.

https://iias.asia/sites/default/files/IIAS_NL51_1617.pdf - same booklet as before.

Ram Singh was a keen and talented photographer. ‘After his demise, the king was popularised to a great extent by Thomas Holbein Hendley (1847-1917), Administrative Medical Offi cer and Secretary of the Jaipur Museum. Following the installation of a hugely acclaimed exhibition at the Niwas Palace in Jaipur, as a tribute to Ram Singh II in 1883, Hendley extended his realm of infl uence all around Rajasthan, thus establishing the prominent role of photography in the region.’

0 notes

Text

15/04/19 - comparisons

Presentation of comparisons I can use to illustrate points in podcast.

0 notes

Text

Podcast Plan!

Podcast Breakdown

1. Title Screen at beginning have a name for the collection and the many numbers!

2. What attracted it to me? What is the story of the miniatures, what influenced the artist and for what purpose was it made? How did the cultural exchange occur? Was it limited or did it flow freely?

3. Show general photographs or footage of a few of the collection – how many exactly do I have? CHECK PHOTOS AGAINST THE NUMBERS! maybe entire collection to show how big it is? She sent me 30. I also photographed 30.

a. Maybe introduce the book at this point, and then describe the ordered way its laid out and what this gives us – each page is organised by region and then chronologically on the page.

b. Say that we have a mix from a few different pages of the book – so a few different regions

4. Context: General history of miniature painting + history of the time in Rajasthan

a. The journey of the paintings (their original form… to miniatures that we have… to the book) – because the differences between the miniatures in our possession and the ones in the book are minimal, it is likely that a lot of thought went into the composition, facial construction, decoration and style of the paintings in our collection, so they could be quickly and easily transferred into the book. So the main westernisation would have taken place from the original paintings to these ones….

i. Hendley said something about the wide sources used.

ii. Here could bring in the nature of the book itself, which has roots in miniature painting

1. Nature of book… are there similar ones??

iii. Say they were donated to the museum by Mrs Hendley

b. Sort of bring in westernisation here/company style of painting??

c. Can maybe say that a cultural exchange in miniature painting was not a new phenomena, but one that had originated from the outset of the art form… have research!

d. Changes along the way!

i. Oval shape etc…

ii. Painting to painting changes (in pictures)

iii. Also the changes that occurred with the introduction of photography

5. History of the book itself and Dr Hendley

a. Where he got the paintings from

b. Purpose of the book… He had a history of documentation

i. Similar to English books which document important people – so the very existence of the book, not only its stylistic features, are a result of the Westernisation of miniatures.

ii. There is plenty of scope for Orientalist discussion within this – focusing on the British Raj and more widespread attitudes of colonisers.

c. Book cover etc

d. Look at the purpose of portraiture in the English and Indian courts… had they always served the same function in both? A status symbol amongst the elite,

6. Painted photography & its connection with the history of portraiture in India?

7. Comparison between Elizabeth and Shah Jahan – this is a good comparison. Hendley maybe borrowed from both, so the miniatures I have are a meeting of the two. (Why Elizabeth and Shah Jahan? Because they were contemporaneous? Because Hendley decided to go that far back?

8. End with something about the miniatures themselves being works of art to be appreciated, despite their function as portraits. They are a Segway from the functional book to the romantic portraits of maharajas. And a bridge between the post and the pre-colonial India (because some of our miniatures were before the British and retain their miniature painting techniques – which ones??)

0 notes

Text

15/04/19 - Further research into miniature portraiture

Equestrian portraiture was another way to express royal standing, as seen in an image of Maharana Sangram Singh of Mewar (2004.403). He sits on a rearing horse flanked by attendants holding fly whisks, following a long-standing convention of dynastic portraiture. A radiant halo further aggrandizes the king and references his dynastic descent from the sun god.

& lots of beautiful information about Indian miniatures! - At this time on the plains of Rajasthan, it was primarily Krishna, in all his varied roles, that fueled the pious devotional imagination of patron and artist alike. The stories associated with Krishna’s life formed the basis for a major pilgrimage tradition that especially focused on the region of Braj. In one image, Krishna appears as the auspicious seven-year old Shri Nathji in the act of lifting up Mount Govardhan to protect his devotees from a violent storm invoked by the god Indra (2005.342). He is dressed to mark a specific festival, and his physical form is based on one of the self-manifest stone sculptural images (svyambhu) that stood at the center of this devotional tradition.

Behrendt, Kurt. “Poetic Allusions in the Rajput and Pahari Painting of India.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/rajp/hd_rajp.htm (October 2016)

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mugh_2/hd_mugh_2.htm

Sardar, Marika. “The Art of the Mughals after 1600.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mugh_2/hd_mugh_2.htm (October 2003)

Shah Jahan’s rule was forcibly terminated by his son in 1658. Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707) held increasingly orthodox Sunni beliefs, and his reign saw the decline of Mughal patronage of the arts. Early portraits of him do exist, and he commissioned some notable architectural projects such as the Pearl Mosque (in the Red Fort at Delhi), but in 1680 he banned music and painting from his court. The emperors who followed him were too weak and the state too poor to support the production of sumptuous paintings and books as before; under Bahadur Shah (r. 1707–12) and Muhammad Shah (r. 1719–48), there was a slight resurgence in the arts, but the 1739 raid of Delhi by Nadir Shah caused much of the city’s population to flee and the artistic community to be permanently dispersed. By the 1800s, the Mughals were nominally still emperors of India, but under the protection of the British.

The reduction of artists in the Mughal painting workshops by Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb meant that a number of artists had to find new work, and many regional courts benefited greatly from the influx of former imperial employees. Painting at the Hindu Rajasthani courts such as Bikaner, Bundi, and Kota, and at the provincial Muslim courts of Lucknow, Murshidabad, Faizabad, and Farrukhabad, were all transformed as Mughal artists provided fresh inspiration. Among the important subimperial patrons of the early period was ‘Abd al-Rahim Muhammad Khan-i Khanan (1561–1626/27), commander-in-chief of the Mughal armies under both Akbar and Jahangir. A copy of the epic Ramayana (1597–1605)—with 130 illustrations (2008.359.23)—and six other manuscripts can be attributed to his atelier.

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/55.121.10.21/

‘Mughal court painting during the reign of Jahangir’s son, Shah Jahan (reigned 1628-58), concentrated on portraiture’

‘Real portraiture was a novelty in India. Earlier Indian portraits did not attempt to capture a persons’ likeness, but concentrated instead on presenting recognizable symbols of their subejct’s rank in society. Starting with Akbar and gaining in number during their reigns of his successors, the new Mughal innovation of portraits with actual like-nesses became immensely popular’

‘in this peerless equestrian portrait, “every jewel, sash end, and whisker are as perfect as [Sha Jahan’s] smile”’

‘Note the emperor’s gold halo, a symbol of imperial power borrowed from European art.’

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=TTk_DAAAQBAJ&lpg=PP1&pg=PA24#v=onepage&q&f=false

Divine Pleasures: Painting from India’s Rajput Courts – The Kronos Collections’ bt Terence McInerney

0 notes

Photo

25/03/19 – 14/04/19 I was thrilled to be able to visit Rajasthan in the Easter holidays! This was one of the more happy coincidences I’m sure I will ever experience. Spent 3 weeks surrounded by miniature paintings and gained a truly in depth understanding of the period of the maharajas.

A highlight was visiting Chitrashala in Bundhi where I was given a tour around the beautiful gallery of miniature painting frescos. I was informed by the guide of the importance of marriage alliances between Rajasthani and Mughal kingdoms in order to bring the chiefs under Mughal control. This was demonstrated in the blue and green turquoise colours that filled the room - staple colours from both traditions. I was also taught about the significance of the green and gold halos, which indicate regality.

1 note

·

View note

Text

20/2/19

Having read both Said,E.W. (2003), Orientalism, London: Penguin. and Bhabha, H.K. (1994/2004), The Location of Culture, London: Routledge. some notes on their impact to Dr Hendley’s book....

Said and Bhabha present different interpretations on how the Orient has influenced and been influenced. While Said focuses on the mindset of the West when examining and being exposed to Oriental ideas, Bhabha proposes what happens when this cultural interchange occurs. Both views are evident in Dr Hendley’s book and below are some examples:

- Oval shapes: Bhabha would describe this as occurring due to the influence of cultural interchange. Dr Hendley imposes Western aesthetics onto the Indian style miniatures.

- restriction to just the bust (i.e. from what is usual which is entire body) - again Bhabha’s interchange.

- Said’s reasoning can be drawn upon when examining Dr Hendley’s intention in creating the book (i.e. to document the rulers). This recording and document is something Said describes as a Orientalist act to rationalise and categorise.

- Said’s views are also prevalent when examining why Dr Hendley chooses to go back to the time of the Mughals, and includes a sketch of Elizabeth. This was because he was interested totally and solely in the history of India that involved British influence or presence. As the English had first landed in India during the reign of Elizabeth we can see this inclusion as setting the pace for the book’s Orientalist viewpoint.

0 notes

Text

15/2/19

Digital Rare Book:

Memorials of the Jeypore Exhibition 1883: Razm Namah or History of War

By Thomas Holbein Hendley

Volume IV

Published by W.H.Griggs, London - 1883

The Jeypore Exhibition of 1883 was regarded as among the most important industrial exhibitions of 19th century, where specimen of the best art work of India was curated. Credited to the arduous efforts of Thomas Holbein Hendley, a British officer in the princely state of Jaipur, the Exhibition was primarily an attempt to showcase local skills.

https://www.rarebooksocietyofindia.org/postDetail.php?id=196174216674_10151934442946675

A permanent memorial of the Exhibition was produced as a four-part set of illustrated volumes, authored by Hendley and commissioned by the visionary Maharaja of Jaipur.

0 notes

Text

10/2/19

Research areas for Dr Hendley’s miniature paintings:

1) Westernisation process of miniature paintings (2 step)

2) Purpose of publication

3) Why were they not photographed? (Physiognomy)

4) Comparison with Elizabethan miniatures

a. Oval framing is evident from the initial search.

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/a-history-of-the-portrait-miniature/

From the V&A collection I managed to obtain some useful images to demonstrate the oval shape I am referring to in the book:

e. Indian miniature painting research: Beginning from the Pala style of miniature paintings, several schools of miniature paintings evolved in India over the course of several centuries: https://www.culturalindia.net/indian-art/paintings/miniature.html

i. Pala School

ii. Orissa School

iii. Jain School - Some of the exclusive features of these paintings include portrayal of enlarged eyes, square shaped hands and portrayal of stylish figures. Also, the colors used were often vibrant and most often than not, colors like green, red, gold and blue were used. The enlarged eyes indicate a Jain school may have been adopted in Dr Hendley’s miniatures.

However… the article below stipulates that they are: ‘The style of painting from which the embellished image in India derives, namely pahari folk paintings and even Mughal miniatures, is, sadly, little-researched.’

This article provides extensive information on the medium of ‘painted photography ’utilised in Dr Hendley’s book: https://iias.asia/sites/default/files/IIAS_NL51_1617.pdf

‘Hendley’s publication entitled The Rulers of India and the Chiefs of Rajputana (1550-1897), offers some clues about the development of the painted photograph and its overt connection with the history of portraiture in India. The rulers here are depicted in oval thumbnails, concluding in the centre where the fi rst and last ruler are strategically positioned facing each other. This compilation is one of the most lucid representations of the development and refinement of the artist’s vision through three centuries, beginning with a representation in Pahari style and ending with a frontal, photographic exposé (fi g.2). In his Preface, dated 21 April 1897, the author recalls the names of several artists, including ‘Pana Lal’.

This article provides incredibly useful information on the impact of the advent of photography on Dr Hendley’s book. This was one of the key questions that had occurred to me when beginning my research - as photography was a prominent form of art at the time, why was it that Dr Hendley had not chosen to photograph the original paintings. The process of creating miniatures (in our collection) seemed overly laborious and outdated. This article drew my attention to the photographic like paintings in the middle of each page, highlighting how Dr Hendley had used photography where available. This can be seen as a betrayal of the traditional techniques of miniature painting, although it is also true that photography was a growing art form in India.

- Portrait of Shah Jahan: (https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O113210/shah-jahan-painting-bichitr/ )

All the images above are from the V&A collection. ‘Compare these images to miniature paintings of Elizabeth

Indian miniature painting collections:

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/nov/02/james-ivory-indian-miniatures

0 notes

Photo

5/2/19 - Today I viewed the miniatures in the Oriental Museum’s collection first hand for the first time! What struck me instantly was how small they were. It is difficult to gauge height from only seeing images on a computer and I was shocked at their size, which was much more similar to the oval shapes in the book than I had anticipated.

I thoroughly enjoyed examining them closely, and noted down some features that I wanted to examine in greater detail: the eyes and the back ground colours which were much brighter than i remember seeing in the book.

0 notes

Text

30/1/19 - Research into Elizabethan Portraiture

The cult of Elizabeth : Elizabethan portraiture and pageantry

Author: Strong, Roy.

Publisher: London : Pimlico

Creation date: 1999

Details on Nicholas Hilliard’s miniature painting of an unknown Young man amongst roses ‘is perhpase the single most famous portrait of the Elizabethan age.

Image: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/y/nicholas-hilliards-young-man-among-roses/

Nicholas Hilliard was an English artist, born in 1547. He is most renowned for his portraits of members of the English Courts during the reign of Elizabeth I. This miniature painting is fascinating. Parallels can be drawn between it and contemporaneous Indian miniatures. There is natural imagery, a full standing figure and ornate decoration. The main contrast however is the oval frame, which is unique to European portraiture. It is one of the main features present in Dr Hendley’s book.

Strong explains the main motif of the portrait as love-sickness and points to Reynolds’ indication of meaning in the roses. Who the man in the portrait is remains a mystery but there have been a number of suggestions. David Piper ‘made the daring suggestion’ that he is Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex and Strong agrees but adds the caveat that the ‘evidence which bears this out belongs to a wider context than that of physiognomical likeness alone’. He describes the image as ‘rich in allusions’ and places it in the context of Elizabeth’s reign, directly after the Armada. Other parallels can thus be drawn between Indian miniatures and this depiction of a love interest. It would be apt to describe Indian miniatures as also ‘rich with allusions’.

This is a miniature painting from Chitrashala in Bundi, Rajasthan (somewhere I will be visiting over Easter). It is a beautiful fresco of a woman with a playing with a yoyo. Both of these paintings were created at the same time, and each sets the subject in the midst of natural imagery. A significant difference is the stylised eyes in the Indian miniature, which are unrealistic and exaggerated. The Indian miniature is also less true to the natural landscape, using the typical image of rolling clouds in the background.

This book has been incredibly useful in introducing me to the fascinating world of Elizabeth court portraiture and provided me with some incredible useful comparisons.

0 notes

Text

21/1/19 – write up from meeting with Anthony

This meeting was incredibly useful in guiding my research and highlighting some useful areas to start investigating. It also drew me to some possible new areas I had not considered.

If the Oriental Museum doesn’t have a copy of Dr Hendley’s book (which he thought they did but I was told by Rachel that they don’t so he is going to confirm) then it may be possible to order a copy of the book for the podcast. If it comes from Boston Spa then usually its quite accessible and it’s unlikely there will be restrictions on where I can view it.

It was recommended that outlining the entire collection at the outset of the podcast to provide some context would be beneficial. It would then be possible to focus in on one or two of the paintings to demonstrate my research.

Context (of time and place) is important but don’t get too bogged down in it.

Westernisation process (from East to West) epitomised in stylised Western European oval boundaries placed on the portraits would be good to mention - conduct more research in this area, looking at the subtle alterations (or vast transformations) undergone as the paintings were copied across continents. Corruption of the images.

Rationale for publishing is a not so obvious theme – but he liked the idea. There is plenty of scope for Orientalist discussion within this – focusing on the British Raj and more widespread attitudes of colonisers. In my project proposal I lacked discrete reflective analysis so improve this.

Purpose of the commissions as art – to illustrate the book. Anthony reiterated that all art has a market and a purpose in communicating something. These can be construed in different ways and this book is one manifestation.

Another question regarding purpose which I will ask is why Dr Hendley did not just simply decide to photograph the original portraits and put them into the book. This would have been much more historically accurate and less time consuming. This is discussed in greater detail below.

We then discussed the history of miniature paintings in both British, Islamic and Hindu contexts.

Key question: Why did he chose to do them in miniatures and not another style? It could be because the initial paintings of the rulers were miniatures themselves and he was seeking consistency between the illustrations in the book and the original portraits. Anthony proposed another idea: the book commences its cataloguing of rulers from 1550 which coincides with the rule of Elizabeth I. During her reign the period of instability that had pervaded the English monarchy was over and the country was much more stable. This created an environment in which art could flourish which it did with might in her court. It became very stylish to have your portrait painting in miniature style. Thus, it is possible that Dr Hendley had this parallel in mind and it would be fascinating to compare the miniature paintings of India with those fashionable in Elizabethan England. The two mediums would have developed independently up to the time of the British Raj when a catalyst for sharing motifs and knowledge was created. Anthony mentioned that a key point of comparison would be to compare the miniatures of Elizabeth I and Shah Jahan. Both rulers have miniatures painted of them standing on a globe. These parallels developing contemporaneously on different continents are intriguing. The similarities between the English miniature paintings of the time and the ones conducted by Dr Hendley may inform the idea of ‘westernisation’.

Anthony also liked my proposal to attempt to track back and find some of the original portraits of the rulers in order to aid the comparative narrative of my podcast. He recommended beginning my research with google.

Another possible aspect of research that was brought to my attention was the obsession with physiognomy (the study of faces) that was prevalent in the late 19th century. This originated from Darwin’s evolution of species work which attempted to establish how humans had evolved. One aspect of this was the idea that the white, British, civilised male was more developed than the black or brown people of other continents who were a more primitive form of the human species. They also aligned this theory of physical development with intellectual prowess, attributing lower intelligence with more ‘primitive’ species found outside the West. This then sparked the ‘physiognomy’ school of thought which attempted to identify certain characteristics through facial features. This applied to both ‘developed’ and ‘primitive’ races.

Examining this idea and any relevance it may have had to Dr Hendley could be useful in answering questions such as why he did not decide to photograph the rulers. The alteration process that the paintings underwent as they were copied and then copied again would lend itself to certain features being exaggerated – which I noted when viewing the book.

A key figure in the physiognomy practice is Lavater. He produced a volume of facial types. Below is discussed how this inspired Degas in his piece the Little Dancer of Fourteen Years.

Anthony pointed out to me that the face of the Little Dancer of Fourteen Years by Edgar Degas was designed using Lavater’s face theory. Degas believed that the ballerina’s who were usually from the working class of France were less evolved/less civilised than his class, calling them an ‘animalistic thing’.

In Italy in the late 19th century, a sociologist called Lombrozo claimed that you could identify the degree of criminality through facial features which was also linked to the degree of civilisation.

Lots to think about!

0 notes

Photo

Photographs from Dr Hendley’s book, viewed at the National Art Library

0 notes

Text

10/1/19 – National Art Library trip to view ‘The Rulers of India and the Chiefs of Rajputana’

I finally managed to view Dr Hendley’s book in the National Art Library in the V&A. I gained a valuable insight into both the rationale behind the book, and the substance of the book itself. My thoughts are catalogued below.

From the preface of the book, this sentence from Dr Hendley stood out: ‘I have already published several works on the art treasures of the Chiefs: but it occurred to me that no work would be more interesting than one on themselves’. It appeared that Dr Hendley’s fascination with India stretched beyond its art, reaching an arm into the people of India themselves. The book is undoubtedly a form of art, meant to communicate the legacy of Rajasthan’s Maharajas through the beautifully classical and traditional style of miniature painting. Through this illuminating line in the Preface however, it became apparent that Dr Hendley had an independent, fresh interest in the Rulers themselves, and a desire to direct his research down a more human route.

This raised fresh questions for me. My most burning grew out of the idea of this documentation. Although the paintings were clearly following a very traditional miniature style (bar a few notable details), the very nature of the book as a anthology, a dictionary, a guideline, a register, of 300 years worth of rulers of Rajasthan fascinated me. I am sure that research into similar books will illuminate the motives behind this documentation - engaging with this alongside colonial themes will be interesting.

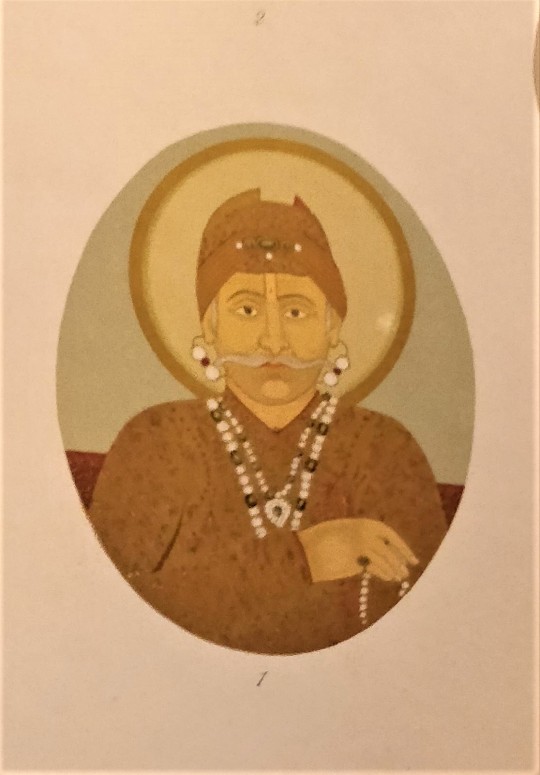

Notably the book also contains portraits of British Rulers from Queen Elizabeth and the Governors-General and the Viceroys, as well as the Moghul Emperors from Akbar himself – hence the title the Rulers of India and the Chiefs of Rajputana (as the portraits include colonial and pre-colonial rulers of India). Hendley says in the preface: ‘The religious toleration of the latter (Akbar) I have been able to indicate by an unique miniature, in which he is shown wearing Hindu sectarian marks.’ The photo below is Akbar. I was able to figure this out because of the useful key used by Hendley to document and label each portrait. The '1′ just below the painting co-ordinates to a ‘1′ at the bottom of the page which contains the name of the Ruler and the year in which their reign commenced. Below is a photograph of the entire page.

From reading on in the book, I withdrew even more useful information. The introduction reads ‘although the greatest care has been taken to obtain reliable portraits, it is certain that some are of but a conventional type; and, in judging of most of them, it must be remembered that very few native artists are capable of taking a portrait in full face.’ ‘The collections of the Princes have been carefully studied, and in some cases (especially in that of the Emperors) very many portraits have been examined and the best chosen for reproduction. On the whole it may be safely asserted that the most characteristic and reliable representations of the notable men… have been selected.’

The first part of the passage illuminated to me a feature I had found very interesting about the book. Most of the portraits are in profile, apart from certain ones on each page which show a full frontal face. When examining the miniatures in the Oriental Museum alone, I had not been able to make this distinction as the collection does not include any front facing portraits, however, when examining the book, the distinction became apparent. While the mystery of precisely why some remained undetermined, the recognition that the portraits were conducted in side portrait (an unusual concept in European portraiture at the time - I will research this comparison later) because this was the ‘conventional’ type of portraiture was helpful.

The second part of the passage was also enlightening. A gaping hole in my knowledge was how the miniatures in the Oriental Museum had come to be. What source had they been copied from? Was it many source or one image that was used? Were they copies of original paintings? How were these sources acquired? Examining the passage from the introduction these questions began to be answered. I discovered that ‘very many portraits have been examined’ for each Maharaja, and that the purpose of this extensive analysis had been to achieve ‘the most characteristic and reliable representations of the notable men’. I found this incredibly enlightening to read. The insight I had hoped for had enabled me to visualise the detailed process behind the individual miniatures in the Oriental Museum. I understood better the painstaking work that must have been conducted to ensure historical accuracy. I also discovered that many of the original paintings had come from the ‘The collections of the Princes’ which were ‘carefully studied’, so I was no longer in the dark about the source of the original paintings.

Overall, this was an incredibly informative and inspiring visit. The miniature paintings were bought to life and took on new meaning as I read about their creation. Many more questions have arisen in me however, and I look forward to honing my research! I will endeavour to understand the mystery of the full face painting on some pages, will conduct a comparison between some of the book images (which I photographed) and the Oriental museum miniatures, and will delve deeper into the idea of a book for documentation being rooted in colonialist attitudes. Lots to think about!

0 notes