Presley || @sonofhistoryJames Monroe historian currently writing a biography and compiling his papers

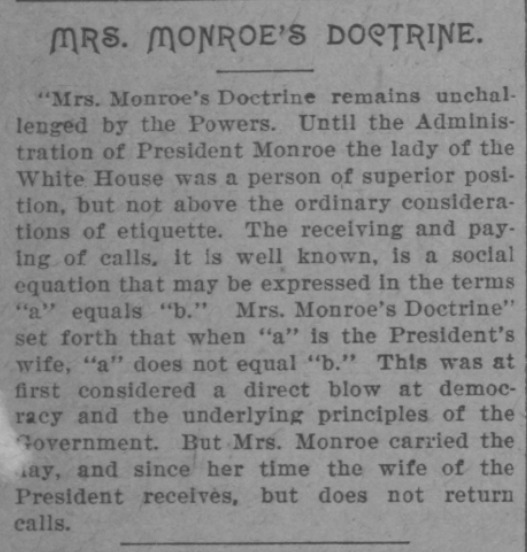

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Quote

[Thomas] Jefferson ordinarily said (often to his regret) in his letters what was on his mind at that time. In mind and temperament Monroe differed completely from Jefferson, and this is reflected in his correspondence. Monroe … almost never touched upon any subject in his letters except politics … he had a huge library (at least 3,000 volumes) … that he read widely, but except for one or two instances books and writers never figures in his letters [except to DuPonceau in his army days]. He shared … common … interest in science … but he never discussed such subjects in his letters. He was … interested in argicultural reform … none of his farm records survive. Monroe was a rather phlegmatic man, who tended to reflect before acting . . his letters lack the spontaneity so characteristic of Jefferson’s correspondence. Frequently Monroe recast his letters several times before sending them. … It would not be correct to call Monroe … an average man, for his talents were considerably above the ordinary … he was remarkable reticent …

James Monroe: The Quest for National Identity, Harry Ammon (via sonofhistory)

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nelson Piquet | Brazilian Grand Prix, 1989

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

“When I reached [New York] Mr. Monroe was very thin & feeble, and appeared to be in bad health, which however I am happy to say gradually became better, and before I left it he had regained in a considerable degree his flesh & strength. Mrs. Hay is with him, & has become very fleshy.”

—

Edward Coles to James Madison, 16 January 1831

“Fleshy”

Also, Monroe never would get better and would die in a few months time.

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

Was Marilyn Monroe descended or at all related to James Monroe?

No, they were not.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

People who have a general knowledge and overview of who James Monroe was: Monroe was boring.

People whose only knowledge of James Monroe comes from brief outside research of the Hamilton musical: Monroe was boring.

Me: is interested in Monroe because nobody has taken the time to research and look into him enough to find out about him and because of this never found out how truly interesting he was.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

I found out Eliza Hamilton Holly moved into the house that James Monroe died in.

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Monroe mentions of Edward Stevens:

“Remember me affectionately to all friends of both houses, to Mr. Beckley—to Mr. Yard & Dr. Stevens & families. Tell them Mrs. M. & child are well & desire to be remembered. Very affecy.”

To James Madison from James Monroe, 30 November 1794

“I shall write Mr. Yd. & Dr. Stevens in a day or two to whom & their families present our best respects.”

To James Madison from James Monroe, 20 January 1796

“Mr. Blake late consul at St. Domingo has been here, with a letter from Dr Stevens, & requests me to introduce him to you. I think I heard Mr. Short speak well of him, in respect to his conduct in spain, where he knew him. Dr Stevens speaks of him in the highest terms. I presume he is known to you much better than to me. I shall give him a letter of introduction to you.”

To James Madison from James Monroe, 23 May 1801

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Monroe and Women’s Education.

James Monroe was of the belief that women should have the equal access to education as men were in this time period [x]. Part of this may be because he was educated by his mother who was very well education until he was eleven; when his mother died he helped his elder sister raise his three younger brothers and quit school; he had an exceptionally gifted wife, Elizabeth Monroe, who was educated as a son; and he had two daughters who he raised in the best education they could receive. His more equal view of women was another reason why he had such a strong bond with his two daughters.

From what I’ve seen in his letters about his children, he never seemed to show any period typical dismay and not having a son–he just seemed glad they were alive, worried a lot when they were sick and said Eliza was a loud baby and seemed rather giddy when he wrote of them. When Monroe was Governor of Virginia for two terms, one thing he worked towards was establishing more schools that were mixed between both sexes [x].

James Monroe used to get teased by women because of his reserved and quiet nature [x], this only enhanced him to try and get women to like him more as he traveled with a few of them in 1784. During the American Revolution while serving as an aide-de-camp to Lord Stirling, Monroe would find himself frequently around the company of Theodosia Prevost (later Burr) who Monroe sought advice from–mainly when it came to women. Due to Monroe’s shy nature he reverted into silence every time he was in the company of one women, Nannie Brown whom he found himself attracted to. Monroe wrote to her for advice to which Theodosia replied:

“A young Lady who either is or pretends to be in love is… the most unreasonable creature in existence. If she looks a smile or a frown which does not immediately give… you happiness… your company soon becomes very insipid… if you are so stupidly insensible of her charms as to deprive your tongue and eyes of every expression of admiration and not only be silent respecting her but devote them to an absent object… she cannot receive a higher insult.”

During his trip around America after his inauguration, Monroe stopped in Nashville in 1819 where he requested to visit the Nashville Female Academy, a school dedicated to women’s education and quickly growing to be the most renowned in the country. When he got there, the school officials marveled at how the president had no guards with him. Funny thing is that everyone was telling Monroe it was a waste of time to visit, but he insisted he had to visit. He didn’t just visit, he stayed from eleven in the morning until well into the late night, giving no less than eighteen toasts and visited two more times during his nine days in the city. At the dinner table, he sat with the students. At the beginning of his visit, he gave a speech to the two hundred students [x]. In the speech he said:

“I cannot express in terms too strong, the satisfaction which I derive from a views of this Seminary. The female presents capacities for improvement, and has equal claims to it, with the other sex. Without intermitting our attention to the improvement of one, let us extend it alike to the other.”

In summary, he was very impressed with the school and both sexes are entitled to equal improvement. He asked, that instead of focusing their attention on one sex, why cannot they be alike or equal?

While still Secretary of State in 1816, the Russian consulgen Nicholas Kosloff was charged with raping a teenage servant who lived with him. Monroe wrote of it to Thomas Jefferson:

“mr daschkoff has pushed his demand of reparation, for what he calls an insult to the Emperor, by the arrest & confin’ment of his consul genl at Phila, on the charge of committing a rape there, with the utmost degree of violence, of which the case was susceptible. By the stile of his last notes, we have reason to expect, that he will announce the termination of his mission, in obedience to o[r]ders given him by his govt, while acting under an excitment produc’d by his misrepresentations, and before a correct statment reached our chargé des affrs, at St Petersburg.”

He was arrested and Russian government asked for compensation, of which the Secretary of State refused to give. It was Monroe who believed the best course would be to recall him for his actions:

“There is nothing that I abhor more in any one, than to see him, make a personal difference with another, the ground or motive of annoying his connections. The opposite course is more gratifying to the feelings of a generous mind, and more likely to elevate the character of him who pursues it.”

Kosloff was never able to be charged for his actions, as the case was given to the Federal courts but the Federal courts deemed it a local case and handed it back. “Of which description of offences the courts of the United States do not cognizance.” Monroe wrote to Levett Harris.

Cognizance: knowledge, awareness, or notice

Monroe problem with the United States and the case was that they were not taking notice of what had happened and neither were they attempted to be aware.

In 1819, Emma Hart Willard took the move of expressing her wish of expanding women’s education “A Plan for Improving Women’s Education” it was called. Her ideas caught the attention of James Monroe who lean’t support for her actions [x]. She sent her writing at a request to Monroe as well as a few other founders.

In a speech to the Virginia General Assembly, Monroe argued that:

“in such a government education should be diffused throughout the whole society, and for that purpose the means of acquiring it made not only practicable but easy to every citizen…” [x]

James Monroe did not believe in the exclusion of women in education and thought a good education for women which was usually restricted to the wealthy should be made better accessible to every being. He once remarked:

“I take a deep interest…in the success of female education; and have been delighted, wherever I have been, to witness the attention paid to it.” [x]

James Monroe, in conclusion, was all for the equality of education between women and men.

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Monroe was not an affection letter writer, he enjoyed doing most of these things in person. Most of his letters center around politics, believe me when I say that if James Monroe gets emotional in a letter or rather “gushy” that means he truly does mean what he was saying and it is important to him.

46 notes

·

View notes

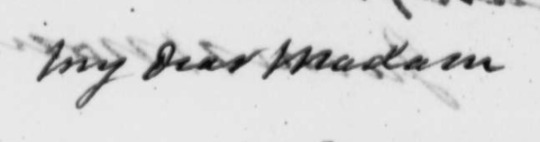

Photo

This was a letter written on July 16th, 1826 to Martha Jefferson Randolph from James Monroe after her father, Thomas Jefferson’s death. It is non-transcribed but you can read it here! For once Monroe wrote in extremely readable handwriting.

In it, he expressed “upmost concern” for the well-being of his mentor’s daughter citing “having been connected by close.. ties in friendship”. Not only does he mention the close relationship he attained with Jefferson but with the late Martha Jefferson as well in his “youth”, furthering my belief that Monroe grew extremely close with Martha in the summer he spent at Monticello because of the large amount of grief he expressed not only in his correspondence with Jefferson, but with his other acquaintances as well.

He also mentions his close acquaintance and friendship to Martha Randolph. He wished upmost for “welfare of your family”. He begged her to “command” him and if needed in “urgent” business as Monticello, he should always be at her disposal.

49 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This is from The Journal, January 23, 1896, I read it and this guy seriously does not know how to shut up [x].

24 notes

·

View notes

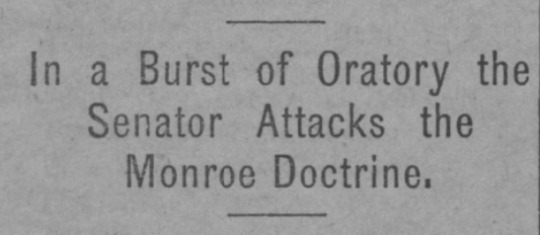

Photo

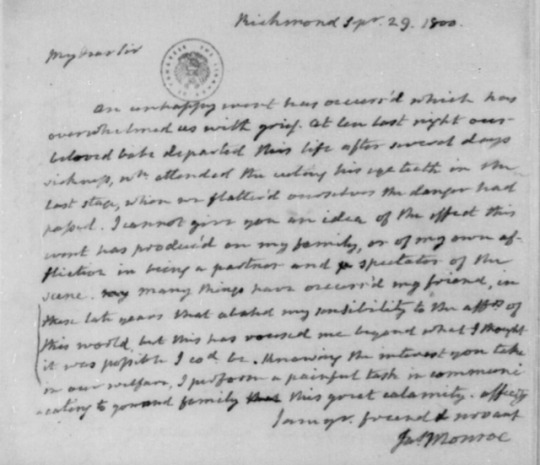

Letter written after the death of James Monroe’s second child, only son, James Spence Monroe.

My dear Sir

An unhappy event has occurr’d which has overwhelmed us with grief. At ten last night our beloved babe departed this life after several days sickness, wh. attended the cuting his eye teeth in the last stage, when we flatter’d ourselves the danger had passed. I cannot give you an idea of the effect this event has produc’d on my family, or of my own affliction in being a partner and spectator of the scene. Many things have occurr’d my friend, in these late years that abated my sensibility to the affrs. of this world, but this has roused me beyond what I thought it was possible I cod. be. Knowing the interest you take in our welfare, I perform a painful task in communicating to you and family this great calamity.

Affectly I am yr. friend & servant

____________________

1) James Spence Monroe was sick his entire fourteen months of life, for a few days he got better until he took a turn for the worst and passed from whooping cough the night before Monroe wrote this letter.

2) James and Elizabeth Monroe never recovered from his death, Elizabeth’s epilepsy got worse and James even as governor cancelled all the events he was to attend as well as a gathering the the capital city of Virginia.

3) James Monroe traveled by horse every day from the capital to his wife to see his ailing son, that night he arrived within the house of his son’s death and was a “spectator” to the scene.

4) Monroe explains that he had gone through so much loss in his life that he believed he was numb to all exposures of grief. He thought he could handle anything–but he could not handle this. In the second most stressful period of his life he was moved beyond what words could explain to this event and “roused” him beyond what he imagined.

5) I have noticed that before this letter, Monroe wrote extremely long letters, all of Monroe’s letters are usually very long, however, until December of 1800, which is two and a half months later, Monroe’s letters are short, small and he always says within them, especially to Thomas Jefferson, that he has nothing of importance to say.

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Spence Monroe

James Monroe first caught Elizabeth Kortright’s eye in 1785 while he was serving as a member of the Continental Congress. The two married on February 16, 1786 at Trinity Church, New York two days after Valentines Day as it is noted in the account books of the church [x]. Ten months later, in December (the exact date in unknown) their first daughter, Eliza Monroe (purposely named after her mother) was born in Virginia. After the birth, Monroe wrote to mentor Thomas Jefferson,

“Mrs. Monroe hath added a daughter to our society, who tho’ noisy, contributes greatly to its amusement.”

When he was away from his new family (though he painfully did not wish to be so) he would inquire in a few letters that were saved between them: “Has she grown any, and is there any perceptible alteration in her?” He called her “a little monkey” and would close them with “Kiss the little babe for me & take care of yourself & of her.“ This would be their last child for thirteen years.

It is unknown exactly why James and Elizabeth Monroe did not have anymore children until thirteen years later but it is speculated that Elizabeth was getting pregnant but she was having miscarriages. Although there no record of any miscarriages (or possibly stillbirths), the fact that the couple were able to produce two children after those long years of “hiatus” does prove she was able to have children after the birth Eliza. Another factor that points to this is that Elizabeth had rather fragile health and late onset epilepsy that caused her physical injury. The miscarriages possibly were recorded but as most of Elizabeth’s correspondence was burned by her husband following her death, there is no way to know.

By 1799 when the Monroes did have another son, James, Elizabeth and little Eliza had already resided all over Europe while Monroe was ambassador to France. In May (exact date unknown) 1799, back in Virginia near Charlottesville, Elizabeth Monroe gave birth to a son, James Spence Monroe and as the father pointed out to Janet Montgomery:

“I was balancing for some time what I should call him, and among the worthies of our country…I should have thought more of the names of Jefferson & Montgomery than any we boast of. But his mother is an old fashioned woman & chose…to follow the old fashioned track of calling him after his father… ”

The elder James was ecstatic with his son’s birth and because Monroe burnt a lot of his letters before his own death, we have only a summary of what Thomas Jefferson wrote back to Monroe, replying to letter written about the new infant:

“[Thomas] Jefferson presents his compliments to Colo. Monroe, & his sincere congratulations to him & mrs Monroe on the interesting addition to their family. he wishes to know how mrs Monroe & the youngster do; and would be made very happy if he could offer any thing grateful to [mrs] Monroe. rice, pearl barley &c sometimes useful to the sick, she probably has: if not, they are here at her service.”

When James Spence Monroe was born, his father was governor of Virginia. Due to the infants sickly health, Monroe was taking trips every other day from the capital to his home and than back again. He did not want to risk having Elizabeth travel in her still weakened condition and neither did he want his child to be on the road while still sickly. James Jr would never reach sound health in his sixteen months of life.

By June of 1800, a smallpox outbreak occurred in the town and Monroe wrote to Madison that “[he is] forbidden to inoculate our child on acct. of his teething & having the Hg. cough, my family will probably soon move up the country.” Due to the babies teething, James Spence had become sick with whooping cough by mid summer of 1800. In August, the family spent time in the country air of their home in Albemarle, thinking the fresh air would be beneficial to the young boy’s health. August 6th, the father wrote to Madison,

“Our child has a fever, did not sleep last night nor on the road. I fear he will not rest to night. We shall have the Dr. with him tomorrow, & his gums lancd as we hope that is the only cause of his present indisposition.”

Teething was becoming so difficult and painful, a surgeon was called to lance his gums to try and alleviate the problem. By August 13th, the symptoms shortly vanished, but J.S. (as he was referred to in Monroe’s letters) was still suffering from a fever.

“I returned from Richmond yesterday (wednesday) and found my child better than when I left him. The dangerous simptoms of the thrush seem to be past, and the hooping cough has nearly left him, so that extreme debility, is his present chief complaint.”

Monroe had to leave to attend to business in Richmond because he was still the governor of Virginia. In the same letter, Monroe noted that the constant rides back and forth between the governors palace and his family home and son’s bedside was taking and toll on James Sr’s health:

“I have been so much worsted by my ride down & back, in the sun, that I can scarcely sit up [today], and my family are not less wearied with the duties which devolve on it in my absence. At present we have no plan but that of ending this state of things.”

The next day on August 14th, the child seemed to be in recovery, Monroe headed back to the capital:

“…since my last my child has had no relapse of his former complaints, but I have recd. a notice which shews I ought to be at Richmd.”

A few times reports were surfacing of a yellow fever outbreak in Norfolk. On August 20th, he arranged for his family to travel to Caroline County to pay a visit to his sister, Elizabeth Buckner, again believing the fresh country air would be good for little James’s health. Writing on September 9th that

“Mrs. M. is gone on a visit to my sister Buckner in Caroline, and writes me she and Eliza are well & the child much improved. By moving him abt. he will I hope get the better soon of those diseases of childhood, & recover his strength.”

Monroe had spent much of August traveling between Albemarle County, where his young son was seriously ill, and Richmond, where he and the Council of State took steps to quarantine Norfolk for yellow fever. In Richmond on the afternoon of Saturday, August 30th, Monroe received information that an insurrection by slaves in the surrounding area would strike the city that night. He communicated with the mayors of Richmond and Petersburg and called out militia to protect the capitol building and public stores of arms and ammunition. Heavy rainfall that made roads and bridges impassable forestalled the beginning of the revolt that night, but Monroe soon received information to convince him that the plan for rebellion was still in place. The legislature was not in session, but with the concurrence of the council on Tuesday, September 2nd the governor alerted all Virginia militia regiments and strengthened the guard on key locations in and around the capital city. He also communicated with local civil officials.

The evening of September 2nd the first group of suspects was brought to Richmond from the vicinity of the Henrico County plantation of Thomas H. Prosser, whose slave Gabriel had been named as the primary leader of the intended revolt. Under Virginia law of more than a century’s standing, the trial of a slave accused of committing a capital offense was to take place without a jury before a court of oyer and terminer assembled for the purpose. According to a 1786 statute, which was a modified version of a bill in the great revision of the state’s law code that Thomas Jefferson and others had drafted some years earlier, a slave could only be condemned to death by unanimous decision of the court of oyer and terminer, and the state would compensate the owner for the value of the executed slave. The first executions for participation in the conspiracy occurred on Friday, September 12th. In the end, twenty-six slaves including Gabriel were hanged. The council agreed to some of the requests from Monroe for pardons or temporary reprieves of condemned men.

The crisis and anxiety of Gabriel’s Rebellion topped with the stress of his son’s sickness was coming to odds with Monroe whose health worsened in this period. Monroe was receiving constant information from his family on the condition of his son. Elizabeth had taken James Spence and went to Fredricksburg where again they believed ever better air would help. The infant’s illness took a turn for the worse on September 20th and on the 22nd, Monroe was writing to Thomas Jefferson that

“…the dangerous indisposition of my child deprives now of that pleasure. Our Infant is in the utmost danger & I begin to fear that we shall want that consolation wh. I was abt. to offer to the afflicted Mr. & Mrs. Carr.”

James Madison cheerfully wrote Monroe back on September 24th that he and Dolley “are glad to hear that your little son has mended so much, as well as that Mrs. M & the rest of you continue well.” James Spence Monroe was on a rapid decline. On the morning of the 28th, Monroe wrote a letter to the Virginia Counsil State saying he was not going to attend the meeting in the afternoon due to the health of his son. After finishing the letter, Monroe set off down his horse unknown that the night of the 28th would J.S’s last, and it would be the final night they would have with their son. He arrived the in the night when the sun had already set after traveling for miles by horse. James Spence Monroe at the age of only sixteen months died at ten pm on September 28th, 1800.

The next day, Monroe wrote a letter to the Virginia Counsil State again, repeated the same reason of why he would not be attending, this time his son was not ill, he was dead. Monroe wrote to Madison and in a letter that featured nothing other than what is below:

“An unhappy event has occurr’d which has overwhelmed us with grief. At ten last night our beloved babe departed this life after several days sickness, wh. attended the cuting his eye teeth in the last stage, when we flatter’d ourselves the danger had passed. I cannot give you an idea of the effect this event has produc’d on my family, or of my own affliction in being a partner and spectator of the scene. Many things have occurr’d my friend, in these late years that abated my sensibility to the affrs. of this world, but this has roused me beyond what I thought it was possible I cod. be. Knowing the interest you take in our welfare, I perform a painful task in communicating to you and family this great calamity.”

The father was witness to his own son’s death after months of poor health and worrying that finally came to a close. Above, Monroe believed that he was numb to loss until James Spence died and that he had known no other grief in his life and that he would never recover. Monroe grieved deeply over the loss and his health dipped into a decline due to his constant travel, and Elizabeth’s health suffered for many months due to her own grief. Neither James nor Elizabeth ever fully recovered.

Before departing for ambassadorship in France in 1803, months after the birth of their third and final child, Maria Hester Monroe, Monroe asked his uncle and mentor Joseph Jones to to place a small gravestone over the spot where his child was laid to rest at St. John’s church in Richmond, Virginia. Saying that he wanted “something more permanent than the memory of our estimable friends who tend his deposit there.” He directed that the stone should bare the buried’s initials J.S.M. and nothing else. Sadly, this grave has never been located.

84 notes

·

View notes

Note

I read your post on James Spence Monroe. Firstly just wanted to say thank you for all the hard work you put into the blog, it's so interesting and incredible! You're knowledge and passion is amazing! I'm wondering is there a response letter from Madison after Monroe tells him of his son's death?

Thank you very much. We do have a reply from James Madison, however, Madison mentions nothing of James Monroe’s loss, his child and said his late reply was “relative to an advance made me sometime last year at Fredbg.” Madison replied to the letter from Monroe speaking of the recent slave insurrection and uprising. The letter is dated October 8th, meaning it took him nine days before answering Monroe’s rather depressing message.

“I ought to have answerd yr. last favor sooner, relative to an advance made me sometime last year at Fredbg., but many interesting concerns have prevented it. That advance was I presume made to Mr. Jones, as I recollect writing by him to request abt. that sum to be applied to my use there. I think too you advanc’d him the cash as he paid the debt wh. I owed on his arrival at Fredbg., tho I rather think it was in sepr. the year before, on his way to the district court. I have seen an interesting paper in several of the gazettes, taken from a Paris paper respecting the state of our negotiation with France.1 By this it appears to be suspended on a strange pretext of our Comrs. that we have no right to put France on a footing with Engld.; a pretext worthy the head of a little lawyer but unworthy a diplomatic agent. The insurrectional spirit in the negroes seems to be crushed, tho’ it certainly existed and had gone to some extent. 15. have been executed, and 10. or 12. more will be on friday next. I submitted the question to the council whether those less criminal in comparison with others, shod. be reprieved that their case might be submitted in all the lights in wh. it may be contemplated to legislative consideration; the council was divided & having no vote those not recommended to mercy by the court will be executed. Our best regards to yr. lady & family. Your friend”

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

James Monroe and the Constitution: Opinions

Two months prior to the Constitution ratification convention, James Monroe wrote to Thomas Jefferson, apparently in friendly terms towards the Constitution. He observed it was created a greater disagreement “among people of character” than any issue since the Revolution. His attitude when he arrived in Richmond had been favorable to the proposed government.Rather than displaying a gradual movement toward the Anti-Federalists, Monroe seemed even more favorable towards the Constitution in April of 1788:

“The people seem much agitated with this subject in every part of the state. The principal partisans on both side are elected. Few men of any distinction have failed taking their part… That it will be nowhere rejected admits of little doubt, and that it will ultimately, perhaps in two or three years terminate, in some wise and happy establishment for our country, is what we have good reason to expect.”

Monroe’s first impressions of the Constitution, the October before, mentioned slight reservations toward the document. In the Spring, he seemed not to have any. James Madison wrote to Jefferson the same month, saying, “Monroe is considered by some as an enemy; but I believe him to be a friend through a cool one.” Monroe would shortly reveal himself to be cooler towards the Constitution that Madison initially viewed.

In light of the pressing need for strengthening the Union, there seemed to be no other course but to accept it, Monroe thought. However, as he listened to the discussions in Richmond and read innumerable essays in the press, he became more and more critical of the Constitution.

In immediate approached of the convention, Monroe completed a forward pamphlet entitled “Some Observations on the Constitution.” Before the election for convention delegates, he had intended to publish his writing the Spotsylvania County, Virginia. However, delays at the printer and the low quality of the final production prevented him from distributing it to the public eye. In the end, Monroe did send his “Observations” to individuals whom he held in high regard such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

Monroe’s pamphlet was a curious work, more a record of the debate waged within himself than a direct attack upon the use of the document. Three-fourths of the lengthy essay was devoted to presenting the reasons the Articles of Confederation had proved inadequate. They had failed, in his judgement, not only because Congress lacked essential powers, but they would also remain unworkable a long as each state had one vote. From his point of view, the arrangement had worked out in Philadelphia was an effective compromise between local and national interests. In spite of this open outlook, Monroe felt certain specific provisions made the whole unacceptable unless they were notified.

In the first place, he took strong exception to the Senate, which seemed to reverse one of the most unsatisfactory features of the old government–the principle of state equality. To correct this defect, he urged appointment of the Senate according to population and direct election by the people. It also seemed unwise to violate the principle of powers by permitting the Senate to share in executive powers. Monroe condemned the grant of power to levy direct taxes as an interference with purely local matters. He insisted any deficiency in revenue from the tariff could be suppled via requisitions.

Monroe was an outlier among the Anti-federalists because he recommended the federal government be given direct control over the militia as it means of eliminating the need for a standing army. He was also exceptional in that he had no fear of executive power as Thomas Jefferson had. Monroe on the other hand, was a nationalist with views standing highly with James Madison in central governmental power than Thomas Jefferson’s states rights. Monroe approved the veto power given to the president. He believed that the president must be popularly elected and chosen directly by the people of their country and this would the sole way of carrying out the duty correctly.

He advocated for strict limitations on the treaty-making power: a mere two-thirds of Congress was not sufficient enough. He concluded by repeating the usually out-cry of the omission of a Bill of Rights. Monroe’s opinions placed him in the anti-federalists of whom were nearly leaning towards of federalist side with slight oppositions and implemented him with the Moderates of the new group. Monroe not only presented proposals for a stronger central unity of the states but also posed far less sweeping objections.

In the letter that accompanied Washington’s copy of the pamphlet, Monroe attempted to explain away his previous support for the Constitution: “I had not at that time examined it with that attention its importance required, and of course could give you no decided opinion respecting it.” Whether he had not truly formulated an opinion before, the young man certainly had now. Monroe became convinced a few articles in the Constitution would lead to the destruction of the states. The nation legislature would be left to manage the enormous “territory between the Mississippi, the St. Lawrence, the Lakes, and the Atlantic Ocean” too large for it to govern.

Monroe was also concerned that the Constitution failed to uphold fundamental liberties, “How are we secured in the trail by jury?”, he inquired. If the nation government is given powers, “unless we qualified their exercise by securing this, might they not regulate it otherwise?… As it is with the trial by jury so with the liberty of conscience, that of the press and many others.” Monroe was flatly opposed to direct taxation provided within the Constitution, believing that I met end in either anarchy or the suppression of such liberties. He believed the government would utilize tyrannical collection tactics and that these couples with oppressive taxes would inflame the people to rebellion.

In his “Observations”, Monroe acknowledge the large “defects” of the Confederation, but cautioned against hastening into the proposed replacement: “Political institutions, we are taught by melancholy experience, have their commencement, mature, and decline; and why should we not in early life, take those precautions that are calculated to prolong our days, and guard against the diseases of age? Or shall we rather follow the example of the strong, active, and confident young man, who in the pride of health, regardless of the admonition of his friends, pursues the ratification of unbridled appetites, and falls a victim to his own indiscretion, even in the morn of life and before his race had fairly begun.”

Monroe was determined that he could fully support the new Constitution: “Although I am for a change, and a radical one, of the Confederation, yet I have some strong and invisible objections to that proposed to be substituted in its stead.” What is the rush? “Is it to be supposed that unless we immediately adopt this plan, in its fullest extent, we shall forever lose the opportunity of forming for ourselves a good government?”

He concluded in his “Observations” an appeal, “To the people of America, to you it belongs to correct the opposite extremes. To form a government that shall shield you from dangers from abroad, promote your general and local interests, protect in safety the life, liberty, and property, of the peaceful, the virtuous, and the weak.” He knew his position would place him at odds with several of his oldest and dearest friends and political allies: “To different in any respect from these men is no pleasant thing to me; but being called upon an awful stage upon which I must now bear a part, I have thought it my duty to explain to you the principles on which my opinions were founded.”

In finality, James Monroe believed the anti-federalists demand of exiling the Constitution with opinions centered around the lack of wished for articles, was not a means for defeating the constitution, but instead, a means by which the ratification convention may use to improve the Constitution and create and government more in harmony with the republican ideal.

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Little things about history tip me off, like the fact that James Monroe was two years younger than Mozart.

52 notes

·

View notes