Photo

Losing Ground

There’s so much to talk about in Kathleen Collins’ 1982 semi-autobiographical indie lovechild LOSING GROUND.

I’m drawn to Seret Scott’s simmering, slow-burning portrayal of protagonist Professor Sara Rogers, who teaches continental philosophy, and feels an existential urge to study the concept, and affect, of “ecstacy.” Sara approaches her quest to experience the feeling of ecstacy anthropologically at first; she is puzzled and fascinated by her painter husband Victor (played by the iconic Bill Gunn), whose reckless artistic free spirit is intertwined with the pleasures and betrayals his manhood entitles him with.

During the course of this essayistic film, Collins creates trippy montages of Sara’s tumultuous intellectual project; she punctuates Sara’s profound questions with a light-hearted humour and offers the viewer Sara’s hallucinatory and erotic visions, journaling her revelations like waking dreams.

—

Ecstacy is decidedly different from joy; it reads as transgressive, narcotic, overwhelming. It is breathless. Closer to death. Crossing over. Woman on the verge. Brimming.

Ecstacy is fleeting, and can perhaps be likened to a kind of mourning. To the memory of the dead, or the one who disappeared. It can be stirred by a kind stranger, or when you suddenly remember you childhood home. Or the memory of ripe fruit; the summer; or last fall, when you lost someone to age and illness. Or the long walk home, interrupted one evening by a long-distance phone call.

Why is the ecstatic a dangerous thing? Is decadence frightening?

When did you last feel ecstatic? Did you also feel scared?

— Aaditya (MICE)

You can watch Losing Ground (1982) FOR FREE on The Criterion Channel here.

17 notes

·

View notes

Photo

TRACEY “AFRICA” NORMAN

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

@zebablay: Tracey “Africa” Norman, the first black trans woman to gain prominence in the fashion modeling world (until the revelation that she was a woman of trans experience during an Essence shoot effectively cut her career short in the 1980s).

220 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Naseeruddin Shah and Smita Patil screentest for Gandhi (Richard Attenborough, 1983) as Mahatma and Kasturba Gandhi; the roles ended up going to Ben Kingsley and Rohini Hattangadi

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1.

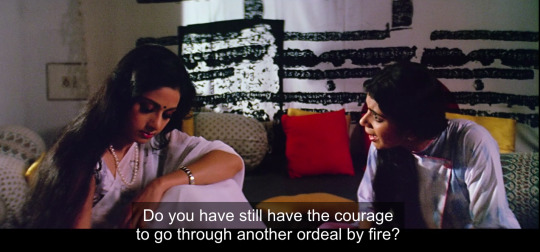

Sridevi as Working Girl

Chandni (1989) was a huge commercial success and the late superstar Sridevi’s breakthrough as a lead protagonist in a Yash Chopra film, with arguably more screen time than both the male leads, Rishi Kapoor and Vinod Khanna, combined.

The film accelerated Sridevi’s metamorphosis into a bonafide top heroine, at-once siren and dame. Sridevi is Chandni; she is also Chandni; “In & As.” Carrying a film on her shoulders as the protagonist and only lead, her task was gargantuan— to emulate both the virginal and sensual, to play, in equal parts, daughter and working girl; a dutiful fiance and conflicted lover.

Chandni’s turn toward leading a young, professional life in the metropolis is seen in the second-half of the film, where we also meet Mita Vashisht in a brief cameo as Kiran, Chandni’s friend and confidante.

In the following scene, Kiran is urging Chandni to stand her ground, and not return to her former fiancé Rohit (Rishi Kapoor), who she thinks Chandni must move on from. Previously, Rohit, who turns paraplegic after being in a plane crash, purposefully rejects Chandni in order to “allow” her a life of ease with someone more able-bodied instead of him. But before this scene, he has now gained mobility in his legs and wants to make a comeback into Chandni’s life (sigh).

In this scene, the camera registers Chandni’s turmoil and interiority by closing up on Sridevi. Sridevi simmers, imploding, leaking a longing and a tension, dilemma, anger even. Although the scene is written for Chandni, Vashisht’s Kiran holds her own with a believable ease and a lived, characteristic intensity.

Vashisht’s screen presence and delivery of dialogue energizes the scene; Kiran’s questions complicate the viewer’s understanding of Chandni’s longing for Rohit, speaking to an implosive sense of being wronged that Chandni’s character has harboured after her separation.

The female protagonist’s “best friend” historically emulates extremes; they are often visual foils, highlighting or underlining the heroine’s virtue, worth, potency. Many a time, the “friend” provided the audience with comic or moral relief at the expense of the her own body or lifestyle choices. Even more frequently, the heroine-adjacent character offered us more possibility, a breach of gender; soft, perceivable rebellions.

It feels as though writer Kamna Chandra, along with Sagar Sarhadi, Arun Kaul, and Umesh Kalbagh, subtly attempted to push the protagonist Chandni’s arc towards transforming into Vashisht’s urbane working-woman Kiran. The writing surprises pleasantly in the second half, in its telling of Chandni’s economic emancipation—beginning from her sheltered, small-town, familial domesticity to her courtship in Delhi to a cosmopolitan life of single womanhood in corporate Bombay. On the verge of an almost biting social-realist bent that feels somewhat provocative for a Chopra flick, the script is forced to encounter a negotiation, fraught with a burden to return to convention: the heroine’s singular marital bliss of first love.

So it seems the writers were probably met with some tension from the makers, made to culminate the story into a relatively conservative, unruffled narrative resolution. When Sridevi’s Chandni returns to Rohit, a certain sociological mesh is held into place; maintaining traits of dutibound sacrifice, emotional generosity, and porcelain, conventional beauty that arguably fuel a culture of the quintessential Yash Chopra heroine.

And yet, despite the conservatism surrounding the airbrushed heroine figure in the late Chopra’s body of work, his typical romantic melodrama—built with a fashionable, restrained excess and economic abundance—does, in fact, regard its female protagonist with a prolonged closeness and an emotional depth. The Yash Chopra heroine is often dolled, dreamy, love-lorn, integrated with ease into society and its conventions. At the same time, she is often reclusive, inebriated with a sensual imagination and spilling with poetic musings, absorbed by her fantasies, a select longing, in a sea of people. The eventuality of his heroine is this: her spectacle marries her intensity; Chopra’s gaze intertwines with the genre of women’s melodrama, the Woman’s Picture (think Bette Davis’ quiet fragility and newfound independence in Now, Voyager or Audrey Hepburn’s outward transformation and inner turmoil in Sabrina).

Yash Chopra’s heroines, Sridevi included, are famously celebrated for their pitch-perfect styling and stellar beauty, setting trends ablaze, from the flowing chiffon sari to sleeveless blouses to monochromatic sheer, translucent salwar kameez.

After Chandni, Sridevi became synonymous with her character’s blindingly white salwar kameez donned as an amorous girl-next-door. More widely pictured is the ultra-traditional yet risqué white outfit she dressed in when imagined by Rohit in a “dream sequence” (musical montage). Here, her midriff is exposed as she sways and dances sensually, alone and surrounded by Chopra’s signature scenery of pristine snowcapped mountains. Her movements are languorous, her limbs seducing, then swivelling, faster, building into a crescendo while the music swells.

With much talk around the attention to detail Chopra exercises in visually presenting his heroines as both virtuous and desirable, many often overlook the emotional complexity and internal strife of his women. He afforded his characters with a dimensionality that mainstream Hindi-film heroines of the 80s and 90s seldom had the chance to essay. The Yash Chopra heroine had the opportunity to portray a substantial, meaty speaking role with dramatic heft and career-defining, scene-stealing moments. She held a bated breath, a quiet applause, among audiences; a winner of hearts, she shined while delivering her turns of phrase, the length or gravitas of which were mostly, if not only, afforded to leading men in films of the time.

Chandni, in particular, sees Chopra’s heroine helm the narrative, testing social boundaries. Veering in her dilemma between her former amour and current admirer, she toes the line of taboo and tradition. Between the timeline of two men, one exiting and the other entering, Chandni finds a room of her own, retreating, growing into the self, her scenes of solitude and reflection imprinting an image of an aspirational working girlhood in the city. That Chopra’s rose tint filters Chandni’s unconventional choices is combative in itself, but it also makes the ground tremble in secret, ever so softly, Chandni ushers a new heroine in a new decade of commercial Hindi cinema.

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

“I think sometimes people are like, “oh, I can’t do that, it’s ballet...” but if you just slip it in and they can do it straight away and be like, “you just did this,” and “that’s called a pirouette,” and “that’s called an arabesque.””

“They’ve done it without realizing it.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

always felt close to Nigar Sultana’s sly looks in Mughal-e-Azam (1960)

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Frank Ocean, photographed by Nabil Elderkin, for Oyster Magazine, 2017

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Charulata (1964), dir. Satyajit Ray

so much of Charulata is about writing, being read, being regarded. Madhabi Mukherjee’s gaze, lowered, absorbs text, and raised, the people downstairs. she rarely sees while also being seen; her most intimate form of contact is through a pair of brass binoculars, a tool that indulges in concealment. in these moments, cool lens cocked on nose, she is framed by a window; she looks outward, and then to a wall indoors, playfully, as though scheming.

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

While directing the music video for Beyoncé’s Greenlight (2006), Melina Matsoukas was inspired by the image of women in little black dresses with prim black stilettos in Robert Palmer’s 1985 song Addicted to Love. Palmer’s dancers, pretend-playing electric guitars, swayed expressionlessly, in unison. Knowles’s backup dancers adorn the same outfits, with hair pulled back into gelled ballerina buns and mouths painted red. They are choreographed more regimentally, feet mounted into ballet-pointe heels, knees browner, with statuesque sheen. The gentle body-hugging fabric of Palmer’s single replaced by bodies wrapped in spotless latex. It’s almost impossible to notice anyone, least of all Beyoncé, sweating.

3 notes

·

View notes