Text

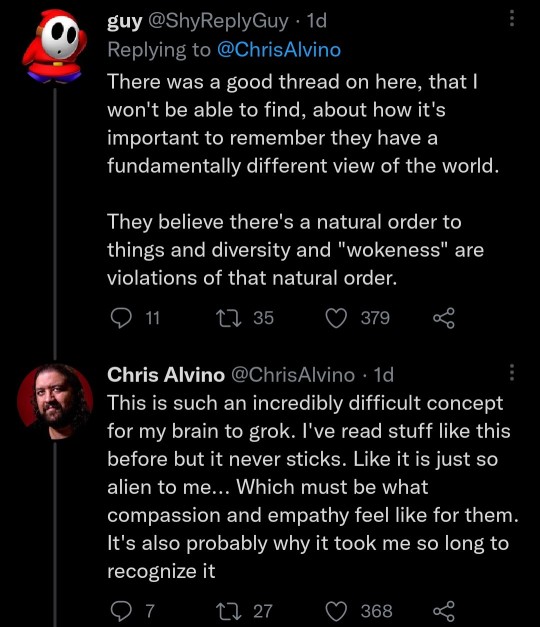

I'm up to the "I dunno maybe children working 13 hour shifts is bad, guys" part of Capital and it feels important to inform people that haven't read it yet that capitalists in the 19th century were not by any means wringing their hands and twirling their mustaches about employing children to squeeze out profits, they were hiring "experts" to write newspaper articles for them, explaining how "well, the socialists have these big demands about an 8-hour work day, and taking Saturdays off, but it's actually just so complicated, it's too complicated for most people to understand, we just NEED to hire children for night shifts because the stamina of their strong, youthful bodies is the only way we can survive as a business! It's science, you see. Economics doesn't work like that, just ask our economics professors at Oxford. You CAN'T turn a profit only working people 8 hours! Trust the experts, they know. It's just so complicated..."

That exact infuriating cadence that you read in New York Times articles, in the Atlantic Monthly, in the WaPo and all the other bourgeois rags where "everything is so complicated, and it's actually a lot more complicated than you think.." that has been around since the beginning. It is nothing new. So the next time you see some op-ed from Matt Yglesias or any of those other guys huffing their own farts about how "complicated" everything is, and how "unrealistic" a 30-hour work week is, remember that Marx was dealing with that exact class of "intellectuals" "explaining" how working 13 hours at age 10 was "vital" to the "moral fibre" of those poor kids.

63K notes

·

View notes

Text

love this passage in which pliny the elder tells us that a beloved raven was killed by a shopkeeper that hated it and the people of rome were so enrages that they put the shopkeeper to death and then gave the raven a more well-attended funeral than some of rome's most esteemed politicians got

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

while we're talking about mayakovsky and disco elysium, i think the suicidal themes are very important, too.

mayakovsky died by suicide in 1930 (shot himself). his poetry is rife with suicidal imagery. it is essential to his poetic persona.

mayakovsky was also a devoted communist up to his death--"the greatest poet of our soviet epoch" according to stalin (there's a lot i can say about that quote itself and what it means for mayakovsky's complicated legacy, but i won't).

mayakovsky believed in the power of communism--especially through poetry--to fundamentally change the world.

he believed that the ideal communist state would eventually achieve actual resurrection of the dead (no, that's not an exaggeration).

he had SO much hope in the communist project. he believed that a better world could exist. at the same time, he suffered extreme disillusionment in the face of NEP communism and literary censorship by the soviet state and personal despair that he ultimately could not overcome.

these facts about him resonate a lot with characters in disco elysium.

there's kras mazov, who shoots himself after becoming disillusioned with his own revolution.

and, of course, there's harry du bois, who is often only a couple of dialogue options away from talking about suicide or even attempting.

mayakovsky wrote: "more and more often, I think / would it not be better to place / the period of a bullet at the end of my sentence?" (the backbone flute)

and eventually, he would. but he also wrote some of the most hopeful words ever written about art, about love, about human ingenuity. those contradictions lived inside him and made his art revolutionary and so utterly him.

i'm not really sure how to end this beyond saying that despair can overtake even the most hopeful and future minded of us all, but there is beauty and hope alongside darkness. disco elysium embodies that perfectly, imo.

284 notes

·

View notes

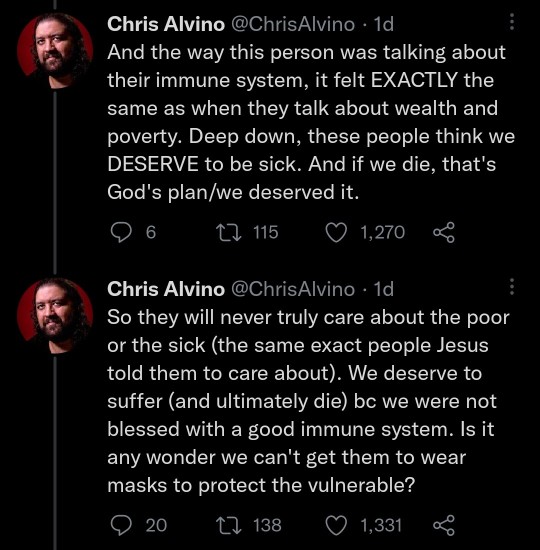

Text

The National Parks Service have purged trans people from the website on the Stonewall National Monument

54K notes

·

View notes

Text

I love visiting people who have some kind of pet reptile because they're always like "would you like to hold the reptile" and I'm like "of course I would" and then the rest of the conversation happens with me just holding a random reptile and the reptile Has No Feelings about the situation. They always just sit there, probably vaguely wishing to return to their heat lamp but clearly exuding an energy of This Might As Well Happen. and then I put it back in its enclosure and go home and the reptile very clearly has no strong feelings about the situation.

51K notes

·

View notes

Text

one of my top ten french behaviors is that i find it deeply jarring to see croissants (as a whole) be considered as "pastries". a Pastry is an éclair or perhaps a millefeuille or lemon tart or macaron. it is colorful and sugary and generally dainty (not always) or indulgent (not always). croissants (including chocolate/almond croissants) are Not! Pastries. but carmine, you cry! what are they then? VIENNOISERIES. like wien. you know. the city. we stole them from the austrians like a william years ago. no yeah no it Is a stupid name. still not a Pastry however,

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

32K notes

·

View notes

Text

It's the 10 year anniversary of Twitch Plays Pokemon, the most important cultural event of our lifetime.

516 notes

·

View notes

Text

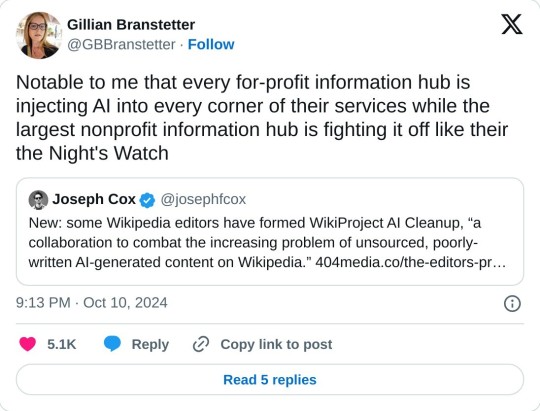

A group of Wikipedia editors have formed WikiProject AI Cleanup, “a collaboration to combat the increasing problem of unsourced, poorly-written AI-generated content on Wikipedia.” The group’s goal is to protect one of the world’s largest repositories of information from the same kind of misleading AI-generated information that has plagued Google search results, books sold on Amazon, and academic journals. “A few of us had noticed the prevalence of unnatural writing that showed clear signs of being AI-generated, and we managed to replicate similar ‘styles’ using ChatGPT,” Ilyas Lebleu, a founding member of WikiProject AI Cleanup, told me in an email. “Discovering some common AI catchphrases allowed us to quickly spot some of the most egregious examples of generated articles, which we quickly wanted to formalize into an organized project to compile our findings and techniques.”

9 October 2024

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

i'm listening to gathering moss, by robin wall kimmerer, and she is talking about a very odd job she was consigned to do, where an eccentric millionaire recuited her to consult on a "habitat restoration". when she arrives, the job they actually want her to do is to tell them how to plant mosses on the rocks in his garden. he wants it to look like a specific, beautiful wild cliff in the woods nearby, with centuries-old beds of moss growing thick and strong. she tells him it is impossible. such a thing would take decades to accomplish.

later, she is called back to look at the progress of the moss garden and is amazed by the thick, well-established mosses. how did they do it? she asks.

then they take her out to the woods and show her that they have been blasting huge chunks of rock out of the cliff, packaging them in burlap, and moving them to the owner's garden.

44K notes

·

View notes

Text

[“The traditional politics of the Vietnamese villager was that of accommodation. “The essence of small people is that of grass,” wrote Confucius. “And when a wind passes over the grass, it cannot choose but bend.” In the days of the old empire the people of the villages did their best to avoid participation in the power struggles of their leaders. They preferred to hold themselves impassive, secret, while the warlord armies passed by, and to commit themselves only when the struggle had already been decided in the heavens. As long as the new rulers guaranteed them a minimum of security, the villagers would accept their authority. To resist was to invite destruction, for the conflict, having no rules, could not be settled except by unconditional surrender. Even the high mandarins did not resist implacable force. If unable to “bend” and serve the new sovereign, they would accept the will of Heaven and commit suicide on the battlefield.

Brought up in the traditional manner, the villagers of the 1960’s had learned that their very lives depended upon their “self-control,” or, in Western terms, their ability to repress those feelings which might bring them into conflict with others. As children they played no contact sports. (When the Westerners brought football to Vietnam, they did not perhaps realize the difficulties the game might provoke.) As adults they took pains to avoid even the smallest argument with their neighbors. Between father and son, superior and inferior, the relationship was even more delicate. When mistreated by his landlord, the tenant, for instance, would tend not to blame the landlord for fear that the conflict might finally break all of the bonds between them. Indeed, his emotion for the landlord might not surface in the conscious mind as anger: he would feel “shame” or “disappointment” that his own behavior or his own fate had brought him to such a low status in the eyes of the landlord.

One former Front soldier gave an excellent illustration of this attitude:

Q. Tell me a little about your background. A. I was the eighth of ten children and we were very poor. We had no land of our own. I tended ducks for other people. We were moved around a great deal. Once I tried to save money and buy a flock of ducks to raise for myself, but I failed. I never married. Once I fell in love with a village girl, but I was so ashamed of my status that I did not dare declare my love to her.

Q. Were you angry at society because of this?

A. I thought if we were poor it was our own fault. I told myself that probably my poverty was the result of some terrible acts of my ancestors. I was sad but not angry.

Such acquiescence before authority had its place within a stable, family-based community, where custom and community pressure insured a measure of economic and social justice. But within a disordered and unequal society, it hardened the status quo and denied not only the poor peasants but all Vietnamese not actually in power a voice in their country’s future.

The villagers often resented their government officials, but they made no complaints, for they saw them as instruments of the distant, implacable power of heaven or Fate which they had no means to influence. In the same way, the students of the Saigon university — the sons and daughters of the Diemist officials — made no protest against the Diem regime until the Buddhists led them to it. Like the poorest and most ignorant of the peasants, they simply assumed that they had no power to change the course of events.

Curiously enough, among all the political groups in Vietnam, the Communists alone recognized this political passivity as a psychological problem amenable to a psychological solution. One PRP directive made a very precise formulation of it:

Daily the masses are oppressed and exploited by the imperialists and feudalists and therefore are disposed to hate them and their crimes. But their hatred is not focused; it is diffuse. The masses think their lot is determined by fate. They do not see that they have been deprived of their rights. They do not understand the purpose and method of the Revolution. They do not have confidence in us. They swallow [sic] their hatred and resentment or resign themselves to enduring oppression and terror, or, if they do struggle, they do so in a weak and sporadic manner. For all these reasons agit-prop work is necessary to stir up the masses, to make them hate the enemy to a high degree, to make them understand their rights and the purpose and method of the Revolution, and to develop confidence in our capability.

The solution of the Viet Minh, like that of the NLF, was the systematic encouragement of hatred. In 1946, just after the French broke off negotiations with the Democratic Republic in Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh began to make a series of speeches that now seem quite uncharacteristic of him. Usually the coolest and least emotional of revolutionaries, he denounced the French not only as colonial oppressors but as perpetrators of the most lurid crimes against women and children. On the battlefields as in the most remote of the villages, his cadres conducted a massive propaganda campaign to call forth the emotion of hatred. Reciting lists of the French crimes (no doubt both real and imaginary), they would produce evidence in the form of artillery shells or corpses and call upon the villagers to describe their sufferings in the hands of the “colonialists” and “feudalists.”8 Hatred was the beginning of the revolution, for hatred meant a clean break in all the circuits of dependency that had bound the Vietnamese to the Westerners, the landlords, and the old notables.

Quite correctly the Party directive equated “hatred of the enemy” with the masses’ “understanding of their own rights,” for shame is anger turned against self. In calling upon the villagers to blame the “feudalists” and the “American imperialists and their lackeys” for their sufferings, the NLF was making a new map of the world on which the villagers might reroute their lives. The enemy was no longer inside, but outside in the world of objective phenomena; the world moved not according to blind, transcendent forces, but according to the will of the people.

In the idea that they might change their lives the villagers possessed a source of power more efficient than a hundred machine guns, for to blame Fate for all injustice was to fire into the air and render any weapon useless. As Ho Chi Minh said to the last of the French emissaries, “I have no army, I have no finances, I have no education system. I have only my hatred, and I will not disarm my hatred until I can trust you.” Hatred was the key to the vast, secret torrents of energy that lay buried within the Vietnamese people, to a power that to those who possessed it seemed limitless and indestructible. As the interview with one prisoner went:

Q. What about the fact that the GVN has planes, armor and artillery and the Front does not? What difference does that make?

A. It is only a matter of course. The French also had planes and armored cars, but they were defeated. The ARVN has had planes and armored cars for ten years and what have they accomplished?… In this war the decisive factor is the people. Weapons are dead things. By themselves they cannot function. It is the people who use the weapons and make them effective.”]

frances fitzgerald, from fire in the lake: the vietnamese and the americans in vietnam, 1972

33 notes

·

View notes