Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Gender and Sexuality Portfolio Post Three: Connection to Popular Culture

The Evolution of Black Feminism: The Yoncé Perspective

In today’s media, there are so many influential people that use their platform to promote certain, and sometimes hidden, agendas. They use music, radio, TV, newspapers, social media, and the internet to create a strong fanbase, and gain support for whatever motive. This status combined with use of the media can be detrimental to influencing biases in any population. However, media can sometimes be used for the greater good. When thinking of Black feminism and how it is portrayed in pop culture, one iconic figure comes to mind: Beyoncé – Queen Bey. Through her expression of Black culture and forward thinking of feminism, Beyoncé has reshaped the gender binary. The goal of this essay is to explain how Beyoncé has redefined Black feminism via revising the gender binary, specifically through critique and expansion.

Now, Beyoncé, being an international entertainer for over 20 years, has published many songs, videos, and performances. I looked at music from her Destiny’s Child days up until the late 2000s, but realized that during those times, she completely fell into the gender binary (possibly) to gain a larger following to the Beyhive. For that, I examined albums from this decade because her feministic approach is much more pronounced. The two songs that will be analyzed in this essay are “Flawless” from her self-titled album, Beyoncé, and “Formation” from Lemonade, her most recent solo album. These songs make the most sense to analyze because they are like a Black feminist/womanist manifesto: they have very public messages of freedom and calls to action for women and men to defend the care and equity of women of color everywhere.

In the first wave of the Yoncé perspective, Bey promotes her personal beliefs of feminism (without huge emphasis on Black culture). Before getting into the beautiful and strategic portrayal of Black feminism in “Flawless”, the problematic retelling of the gender binary will be addressed first. Bey says, “…this diamond, flawless/my diamond, flawless/this rock, flawless/my rock, flawless/I woke up like this/I woke up like this…”, pointing to her large wedding ring and running her hands up and down her body (Beyoncé, 2013). This part of the chorus retells the gender binary through prescription; it sets the superficial standard of beauty and body type while emphasizing luxurious things that women should desire and achieve (Foss, Domenico, & Foss, 2012). However, this example is so minuscule compared to the dominant message of the song which revises the gender binary. Featured on the song is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Nigerian novelist and feminist. She overtly critiques society’s double standard of behavioral expectations between men and women. The following excerpt is featured on “Flawless” and is originally presented in Adichie’s TED Talk, “We Should All be Feminists”:

We teach girls to shrink themselves to make themselves smaller. We say to girls, "you can have ambition, but not too much. You should aim to be successful, but not too successful, otherwise you will threaten the man". Because I am female, I am expected to aspire to marriage. I am expected to aspire to marriage. I am expected to make my life choices always keeping in mind that marriage is the most most important. Now marriage can be a source of joy and love and mutual support, but why do we teach girls to aspire to marriage and we don't teach boys the same? We raise girls to see each other as competitors, not for jobs or for accomplishments, which I think can be a good thing, but for the attention of men. We teach girls that they cannot be sexual beings in the way that boys are. Feminist: the person who believes in the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes. (Beyoncé, 2013).

This message vocalizes gender inequality and responds with a solution: feminism. What makes Beyoncé so influential for incorporating this excerpt into “Flawless” is that it reaches all age groups. It is unlikely that a 13-year-old girl will go on the internet and search this TED Talk. However, she is likely to have Beyoncé on repeat, which would allow her to truly internalize the questions asked by Adichie. Through music, Beyoncé strategically revises the gender binary by placing this societal critique in her song so that it affects any and every age and gender that listens to her album.

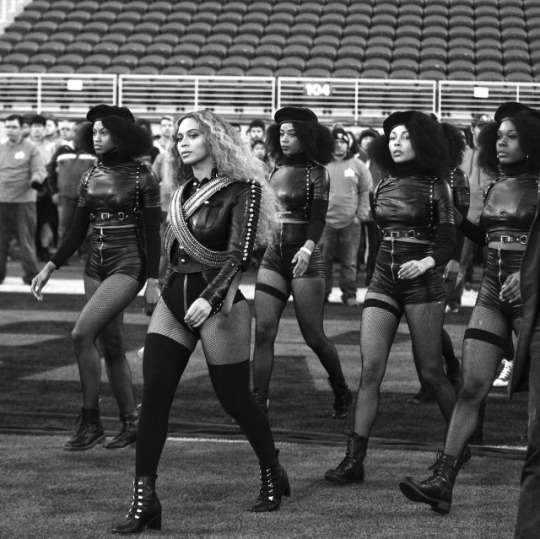

In the second wave of the Yoncé perspective, Queen Bey gravitates more to Black culture and feminism, completely paralleling her work to Black feminism. “Formation” has two powerful portrayals of Black feminism that both critique and expand the gender binary: the music video and lyrics (Beyoncé, 2016). Beyoncé is known for the visuals that accompany her music. Within the first few moments of the video, we see Bey laying on top of a sinking police car in New Orleans, LA, giving the reminder of Hurricane Katrina. It is a political statement of critique, reminding the U.S. of all the (Black) people who suffered and lost their homes and loved ones during the natural disaster with little support of the government to aid in help. A few clips later, Blue Ivy, Beyoncé’s daughter, and friends are playing around in all white dresses. This represents another critique to the citizens and federal government of the U.S. because not many people are aware of, or even care, that there has been a rise in the abduction of Black and Latino girls and women in the U.S (CNN, 2017). This is a second reminder to the United States that little Black girls, and girls of color, are important; #BlackLivesMatter. There is then a scene of Bey and other Black women sitting in a day room dressed in all white apparel from the late-1800s or early-1900s. This visual represents Black women in a stance of power; whereas they would have been slaves or indentured servants at the time, they are dressed in fine gowns, head pieces, and jewels with fans to match. Throughout the video we see Yoncé constantly changing her hair styles. Hair is huge in the Black community and for the Queen to change from a curly fro, to an elegant natural up-do, to box braids that pass the waist adds to the power of versatility in Black women. Lastly, Beyoncé gives the visual of Black feminism by the choreography of her and her dancers literally getting into formation and repeating the lyrics “‘cause I slay” and “we gone slay”. The women made solid lines and often did moves with synchronization. This is a symbol of Black women getting in line and preparing to boss up through their own personal attributes and uplifting one another as they make their way through life. This is a critique of society that wants women to compete and see each other as enemies. Bey’s choreography emphasizes the unity that Black women have simply by the identity itself.

The omnipresence of the gender binary is smashed and revised by Queen Bey when examining the lyrics to “Formation”. In lyrical analyzation, she writes, “My daddy Alabama, mama Louisiana/you mix that negro with that Creole make a Texas bamma/I like my baby hair, with baby hair and afros/I like my negro nose with Jackson Five nostrils/earned all this money but they never take the country out me…” (Beyoncé, 2016). In these lyrics, we see how Beyoncé embraces her roots and Black culture while mentioning financial achievement. The message here is that you can be Black, have financial freedom, and never forget where you came from. This is a general uplifting to the entire Black community. The following lyrics epitomize Black feminism in pop culture because Bey completely contradicts the passive and dependent role of women in romantic relationships:

When he fuck me good I take his ass to Red Lobster, 'cause I slay (2x)/if he hit it right, I might take him on a flight on my chopper, 'cause I slay/drop him off at the mall, let him buy some J's, let him shop up, 'cause I slay/I might get your song played on the radio station, 'cause I slay (2x)/ You just might be a black Bill Gates in the making, 'cause I slay/I just might be a black Bill Gates in the making (Beyonce, 2016).

To a certain extent, these lyrics are an example of the stereotypical “strong independent Black woman” persona. However, in this case, that portrayal is appropriate and empowering. Here, Beyoncé uses the expansion method of revising the gender binary to promote Black feminism; she describes multiple ways of being a Black woman which is contrary to the stereotypical roles of women in the gender binary (Foss, Domenico, & Foss, 2012). In a heterosexual relationship, men are expected to take care of women and be the financial home base. Bey, on the other hand, expands the role of women by making herself the financial powerhouse in the relationship. The last few lyrics are important because they are the product of Black feminism in pop culture. Bey positions herself in the same power dynamic that a White male billionaire is in; she takes on the role of the most entitled and privileged human being. Furthermore, she offers that possibility to other Black women!

In the first wave of the Yoncé perspective, we see how Bey focuses on the gender binary and its hypocritical biases. She addresses the issues without specificity of Black culture. This is to get the attention and support of all women followers. However, in the second wave of the Yoncé perspective, Queen Bey grows her feministic ideology even more, but adds emphasis to Black culture and the love of being a Black woman. This strategy was so tactful because she first gained support for gender equality and later highlighted the social issues around the Black community at large and how society has casted off Black women, all while empowering Black women to push past societal expectations and to be greater than what they have written us to be. Through revision, Beyoncé consistently critiques and expands the gender binary and gives light to Black feminism. Seeing her influence on such a topic effects any and every one that listens to her music and encourages them to take action in order to insure the equity of Black women and women of color everywhere.

References

Beyoncé. (2013. December 13). Flawless. On Beyoncé [Spotify]. New York City, NY: Parkwood &

Columbia.

Beyoncé. (2016, December 9). Formation [Video file]. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WDZJPJV__bQ

Foss, S. K., Domenico, M. E., & Foss, K. E. (2013). Gender Stories: Negotiating Identity in a Binary

World. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Jarret, L., Reyes, S., & Shortell, D. (2017, March 26). Missing black girls in DC spark outrage,

prompt calls for federal help. CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2017/03/24/us/missing-black-girls-washington-dc/index.html

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gender and Sexuality Portfolio Post Two: Connection to Foundational Course Concepts

Understanding an individual through a psychological lens allows researchers to deepen their studies of human cognition, emotion, and behavior. Similarly, observing and recording categorization of a specific identity is essential when examining persons as an entire group through a sociological and anthropological lens. These social sciences are flexible in the manner in which they tend to incorporate one’s identity, which includes those of a gender and sexuality scope. As we define our identities and place ourselves in society, we rediscover the true meaning behind human nature and societal expectations. Creating and enacting an identity is very complicated. There are five fundamental ideas that help us create and defy boundaries preset by society: the social construction of gender, agency, privilege, oppression, and intersectionality. To simple understand human identity, and more specifically in this paper, black feminism and womanism, is to better conceptualize these terms and relate them to one’s lived/living experience.

In relation to black feminism, we see this huge social construction of gender, that is, we see categorization of a label implemented and upheld by society (Foss, Domenico, & Foss, 2013). It can also be seen as the creation and enactment of gender. Before “doing” gender, one must define it. Society constructs what gender is, what it looks like, how people should act accordingly, and what the consequences are if one does not choose to do so. In Patricia Hill Collins’ article on black feminism and social construction (1989), we see the construction of what it means to be a White man, or rather a “Eurocentric masculinist”, opposed to being a Black woman, specifically an “Afrocentric feminist”, in America. She says that this Eurocentric masculinity can completely invalidate black feminist thought by the knowledge-validation process (p. 752). This means that because White men are considered the prestigious group of experts in society, they control the knowledge, or the narrative, distributed to others. Secondly, they remain credible for the sake of power over that knowledge. That being said, White men have control over this knowledge-validation process, which can be used to further suppress Black feminist thought by invalidating their curriculum and experience. This ideology is toxic but very realistic. Contrarily, she says that Black feminists take back this knowledge, and give out their own narrative, through shared histories, family structures, and patriarchal oppression. In other words, we take back our power by reinforcing our experiences and opposing the silence rendered onto us by Eurocentric masculinists. To connect this back to my initial paper, Black girls are opposite of the mythical norm, and therefore find power and resilience through this social construction of gender.

With social construction of any median comes agency. Agency can be defined as choice, or truly believing that one has the ability to make a change on any social, economic, political, etc. issue (Foss, Domenico, & Foss, 2013). Black feminism approaches agency in the simple fact that it is not just defined as feminism alone. It takes on a second identity (which will be addressed in depth later). Black women recognized that their needs were not being met by the original feminist movement, so they decided to create an identity that would; they took the initiative to implement change for the betterment of themselves. “Black women have always been doing the work, creating their own political and social movements that don���t depend on traditional feminism at all” (The Root, 2018). This out-group marginalization caused Black women to create and endorse their own movement for justice. The video quotes Layli Phillips from The Womanist Reader, stating that, “unlike feminism, and despite its name, womanism does not emphasize or privilege gender or sexism: rather it elevates all sites and forms of oppression…to a level of equal concern and action” (The Root, 2018). Again, black feminism and womanism are movements that began with a choice of acting outside of the norm, or in this case (white) feminism. Black feminists essentially became agents of their own cause.

Generally, there is a certain privilege that Black women have, although at times it may seem nonexistent. Privilege is the advantage or power that one from a prestigious group has over those who are stigmatized and outcasted (Launius & Hassel, 2015). This privilege may be intentional or unintentional and can easily be (un)seen in the matrix of social rule. Brittney Cooper, author of Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers her Superpower, explains how Beyoncé is an extremely influential and powerful figure and uses her platform, or her privilege, to express her ideation of Black feminism. The author says:

In 2016, we got Lemonade. It became really clear why somebody like Beyoncé would want to have this sort of arsenal that you get from Black feminism because Black feminism helps you think about what happens when you’re the most powerful chick in the game, you’re married to one of the most powerful dudes, and he still won’t treat you right because he is intimidated by your power…Black feminism can hold that Black girls have hurts and pains that no one else has ever listened to (The Root, 2018).

Beyoncé released one of the most influential albums of 2016 expressing her right to feminism and has recently embraced Black culture and feminism simultaneously. Through privilege of her concerts, Superbowl performances, and triple platinum selling albums, Beyoncé continuously spreads her #BlackGirlMagic by giving voice to the international injustices that all women of color face.

Just as a coin has two side, there is a counterpart to privilege, and that is oppression. Oppression is prejudice and discrimination expressed towards the marginalized or “disadvantaged” group (Launius & Hassel, 2015). It should be noted that there are oppressed people within an out-group (i.e. Black women in the original feminist movement and trans-people in the #BlackLivesMatter movement). Oppression is intentional limitation placed upon all that one can do. As a Black feminist, Maya Rupert expresses why she was always anti-princess until she got a closer look of what the role of a princess really means. The initial thought is that princesses are damsels in distress and are often caught in love triangles: cliché cliché. However, as Rupert closely examined the position of a princess, she discovered that Black girls were not fit for the “typical” criteria.

She explains that White women suit stereotypes of weakness and helplessness which inevitably aligns them with the princess role, while Black women are stereotyped as naturally strong, animalistic, and their beauty has never been acknowledged nor celebrated in Western culture (Rupert, 2018). She goes on to say that, “…it hadn’t happened to me. I didn’t grow up feeling locked into the princess role, but rather locked out…Princess culture — the celebration of a fairy tale version of femininity and romance — damages girls because it offers a limited vision of the roles girls can play, but also because it offers a limited vision of which girls can play those roles” (Rupert, 2018). The author has not experienced the oppression of being the princess, rather she has experienced the limitation, or oppression, of automatically being ruled out of the role because her identity does not fit societal standards. However, there is a brightside to this nuance. Oppression in the media has changed just in the past few years. We now see Black princess: Princess Tiana from The Princess and the Frog, Princess Shuri from The Black Panther, and a real-life princess, Meghan Markle, newly crowned as the Duchess of Sussex. This ideology is a double-edged sword but, overall, gives empowerment to Black feminist even in a state of oppression.

As mentioned earlier, Black feminism embodies a double identity. Generally, the identity itself represents intersectionality. It is a double stigmatization for the simple fact that one who identifies as such is Black and a woman. Launius and Hassel describe intersectionality as a multi- facet construction of an individual’s experience, meaning that we see an overlap in one’s identity: from race/ethnicity, to age, to gender, to sexual orientation, to socioeconomic status, and so on and so forth (2015). In an article written by Holland Cotter (2017), we see the intersectionality in being a Black female artist. In 1965, a board of artists from New York, called Spiral, worked together to produce propaganda for the Black Power movement. Out of 15 African American members, only one was a woman. Black women got so tired of being overshadowed and brushed off, that they branched out and started their own artistic movement called Where We At which essentially was the foundation and development of what Black feminism is today (Cotter, 2017). Defining themselves in the duality of their identity gave them space to voice their needs and requirements of the Black community as a whole. Through this concept, we see how Black women used their agency to overcome oppression. Additionally, we can make the connection that these Black feminists used Goffman’s approach of minstrelization to play into their privilege (Coston & Kimmel, 2012).

Society tends to forget the complex yet simple organization of being a Black feminist. The identity itself is not easy; to experience everyday with (un)intentional jabs at your identity is not easy. But our requests of society are simple; we simply desire having our voices heard and lifted in the name of justice, and to hold others accountable for our suffering. That is all. That is Black feminism. To be defined and socially constructed by society, to embody the intersectionality of gender and race, to be both privileged and oppressed, and to be an agent in which to embrace more is to understand Black feminism on a micro- and macro-level.

References

Alexander-Floyd, N. G. (2012). Disappearing Acts: Reclaiming Intersectionality in the Social

Sciences in a Post-Black Feminist Era. Feminist Formations, 24(1), 1-25.

Cohen, C. J., & Jackson, S. J. (2016). Ask a Feminist: A Conversation with Cathy J. Cohen on Black

Lives Matter, Feminism, and Contemporary Activism. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture & Society, 41(4), 775-792.

Collins, P. H. (1989). The Social Construction of Black Feminist Thought. Signs: Journal of

Women in Culture & Society, 14(4), 745-773.

Coston, B. M., & Kimmel, M. (2012). Seeing Privilege Where It Isn’t: Marginalized Masculinities

and the Intersectionality of Privilege. Journal of Social Issues, 68(1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01738.x

Cotter, H. (2017, April 20). To be Black, female, and fed up with the mainstream. The New

York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/20/arts/design/review-we-wanted-a-revolution-black-radical-women-brooklyn-museum.html

Cox, A. (2014). The Body and the City Project: Young Black Women Making Space, Community,

and Love in Newark, New Jersey. Feminist Formations, 26(3), 1-28.

Deblaere, C., & Bertsch, K. N. (2013). Perceived Sexist Events and Psychological Distress of

Sexual Minority Women of Color: The Moderating Role of Womanism.��Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(2), 167-178.

Foss, S. K., Domenico, M. E., & Foss, K. E. (2013). Gender Stories: Negotiating Identity in a Binary

World. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Jackson, S. J. (2016). (Re)Imagining Intersectional Democracy from Black Feminism to Hashtag

Activism. Women's Studies in Communication, 39(4), 375-379.

Jones, L. V. (2015). Black Feminisms: Renewing Sacred Healing Spaces. Affilia: Journal of Women

& Social Work, 30(2), 246-252.

Launius, C. & Hassel, H., (2015). Threshold Concepts in Women’s and Gender Studies: Ways of

Seeing, Thinking, and Knowing. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Morton, B. (2016). ‘You can’t see for lookin’’: how southern womanism informs perspectives of

work and curriculum theory. Gender & Education, 28(6), 742-755.

Nyachae, T. M. (2016). Complicated contradictions amid Black feminism and millennial Black

women teachers creating curriculum for Black girls. Gender & Education, 28(6), 786-806.

The Root. (2018, April 12). Breaking down Black feminism [Video file]. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i5Sl_Fu47js

The Root. (2018, March 6). Why feminism fails Black women [Video file]. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t9KMtf_e_ew

Rupert, M. (2018, May 12). How a Black feminist became a fan of princesses. The New York

Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/12/opinion/sunday/royal-wedding-princess-race.html

Shaw, J. B. (2015). I don't wanna time travel no mo": Race, Gender, and the Politics of

Replacement in Erykah Badu's "Window Seat. Feminist Formations, 27(2), 46-69.

Smith-Jones, S. E., Glenn, C. L., & Scott, K. D. (2017). Transgressive shades of feminism: A Black

feminist perspective of First Lady Michelle Obama. Women & Language, 40(1), 7-14.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gender and Sexuality Portfolio Post One: Special Interest Topic

Hair styled in box braids with curly roots slicked down by thickened gel. “Medium Dark” on the back of Walgreen’s cosmetic powders. Disgruntled looks from all around. Stereotyped. My innocent brothers and sisters being massacred in the streets by those who are “to protect and serve”. This is why #BlackLivesMatter. The intersectionality of being Black and a woman in the United States, specifically where bigotry and racism have peaked because of those placed in power. This is why we need Black feminism.

Black feminism is the idea that “Black women are self-defining, self-reliant agents of change and knowledge generation” (Smith-Jones, Glenn, & Scott 2017). Black feminism redefines and empowers the intersectional oppression of being a woman of color. I chose this topic because it embodies and enriches my life experience. Growing up on the Southside of Chicago and going to a predominantly White institution (PWI) for undergrad is beyond culture shock. Encountering people who could care less about my experience but me (inevitably) having to know theirs’ like a second-hand vocation is iniquitous. Here I am trying to make sense of the world I live in. Not only understanding my purpose, but the fortitude of it all is found in Black feminism.

When deciding on my topic for this course, I originally decided to investigate womanism. When researching this term with limiters set, I found eight of 11 relevant sources using the Gender Studies database, however I only utilized two. As I typed “black feminism” into the browser, I was presented with 46 articles. It should be noted that about eight of these articles were not in English and nine talked about black social movements separate from feminism, making them unqualified to fit the criteria of my research. Some central themes that were found in the scholarly literature were politics, mental health, being one community reflected in an overall self-identity, rebellion against silence, and resiliency. After gathering data from my ten articles, two were empirical studies: one investigated the school curriculum presented to Black girls by Black women teachers, and the other about the power of womanism that combats psychological distress when previous and current sexual events occur. In addition to this, the next article emphasized the need of Black feminism ideology in order to protect Black women’s mental health. Two articles critiqued neo-liberal movements expressing that Black women’s voices are drowned by the broadened spectrum of intersectionality. Three of the articles discussed democracy and politics and incorporated the resiliency and intersectionality of the #BlackLivesMatter movement. The last two had no specific grouping other than they discussed how music culture and personal narratives add to the sociological effect of Black feminism and womanism entirely.

All of the articles were written by Black women, with the exception of two: one of which was co-authored by an Asian American woman and a White woman, and the other was written by a White man. This speaks volumes regarding the narration and display of African American stories. Two common methodologies used in the literature search were studies that provided empirical evidence for their specific topic, and formal and informal ethnological interviews. Regarding the laboratory investigations, findings for the school curriculum study showed that utilizing the Sisters of Promise curriculum (a guide written by Black women teachers for Black girls) was in fact useful in empowering Black girls, however it had its own contradictions. For example, it explained how Black girls and women are forced to recognize our oppression without resisting it, and to be self-aware for the benefit of others and not ourselves. In the second study of investigation, results showed that Black women who had lower levels of womanism experienced high levels of psychological distress when ruminating on previous and current sexist encounters. High levels of womanism were associated with lower levels of psychological distress from previous sexist encounters, but not necessarily current ones. Overall, authors found that womanism and other social activism promotes resiliency and sense of self-identity as one community. The core message from all conducted interviews was the power and validation of Black women’s experiences and personal stories. Personal narratives help formulate theoretical designs; history (and herstories), discourse analysis, personal narratives, and Black female subjectivity create methodology for Black feminism and womanism (Morton 2016). To speak on our experience is to give hard evidence to our sociological effects of Black feminism and womanism. From all ten articles, the call for futures studies emphasized the need for Black feminism in our schools in order to dismantle covert racism and challenge neo-liberal ideology, to enact a humanistic approach to community and define ourselves under a singular identity, to protect our mental health, and to validate our experiences and personal narratives.

Black feminism and womanism break glass ceilings for Black women. As the literature shows, we need these ideologies and movements to protect us socially, mentally, emotionally, and politically. To bring light to those who are silenced by mainstream society is to break the mythical and heteronormative. As originally cited in “Those Loud Black Girls”: (Black) Women, Silence, and Gender “Passing” in the Academy by Signithia Fordham, “Black girls are ‘socially constructed as the epitome of exactly what whiteness (as maleness) and femininity (as whiteness) is not: dark, sinister, raunchy, belligerent, burly, and licentious’” (Nyachae 2016). Black girls are the opposite of the mythical norm. So let’s be loud, proud, and empowered through the self-identification of one community and Black feminism.

References

Alexander-Floyd, N. G. (2012). Disappearing Acts: Reclaiming Intersectionality in the Social Sciences in a Post-Black Feminist Era. Feminist Formations, 24(1), 1-25.

Cohen, C. J., & Jackson, S. J. (2016). Ask a Feminist: A Conversation with Cathy J. Cohen on Black Lives Matter, Feminism, and Contemporary Activism. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture & Society, 41(4), 775-792.

Cox, A. (2014). The Body and the City Project: Young Black Women Making Space, Community, and Love in Newark, New Jersey. Feminist Formations, 26(3), 1-28.

Deblaere, C., & Bertsch, K. N. (2013). Perceived Sexist Events and Psychological Distress of Sexual Minority Women of Color: The Moderating Role of Womanism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(2), 167-178.

Jackson, S. J. (2016). (Re)Imagining Intersectional Democracy from Black Feminism to Hashtag Activism. Women's Studies in Communication, 39(4), 375-379.

Jones, L. V. (2015). Black Feminisms: Renewing Sacred Healing Spaces. Affilia: Journal of Women & Social Work, 30(2), 246-252.

Morton, B. (2016). ‘You can’t see for lookin’’: how southern womanism informs perspectives of work and curriculum theory. Gender & Education, 28(6), 742-755.

Nyachae, T. M. (2016). Complicated contradictions amid Black feminism and millennial Black women teachers creating curriculum for Black girls. Gender & Education, 28(6), 786-806.

Shaw, J. B. (2015). I don't wanna time travel no mo": Race, Gender, and the Politics of Replacement in Erykah Badu's "Window Seat. Feminist Formations, 27(2), 46-69.

Smith-Jones, S. E., Glenn, C. L., & Scott, K. D. (2017). Transgressive shades of feminism: A Black feminist perspective of First Lady Michelle Obama. Women & Language, 40(1), 7-14.

0 notes