in a telescope lens / and when all you want is friends / i'll see you soon

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

london 21st december

Our last day in London was also the last day of our holiday, at least, the last day that counted. It was a little cooler today, though still not so bad as what we became accustomed to early in the month. Perhaps foolishly we took this as a sign to head out without coats again today, returning first to Monmouth Coffee Company for drinks and an almond croissant. It was a difficult morning for reasons I have left behind there on the streets of the Seven Dials-we walked to the National Gallery for opening at ten, once again with pre-booked tickets. Whilst these places are free to enter as they ever were, showing up without a timed entry is not advisable. The lines for the bag searches alone are long enough.

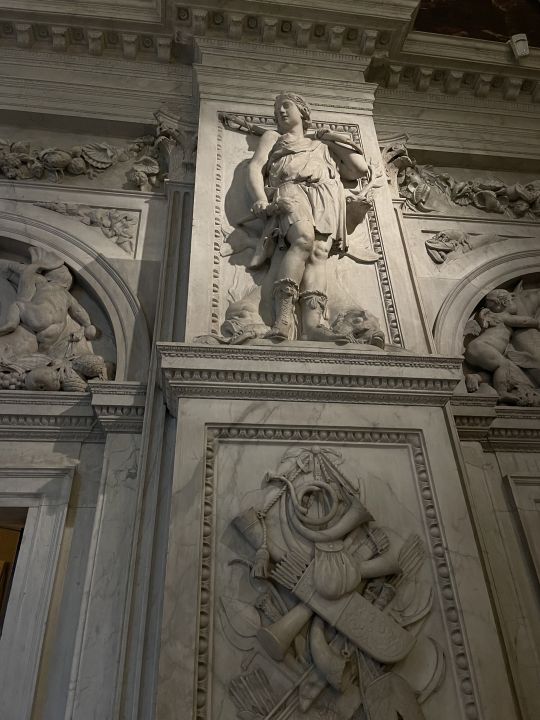

The National Gallery is one of the places well beyond a single visit’s ability to consume adequately, every room is so stacked with works of the old masters and modern greats. It was at least quite peaceful during our visit since we were some of the first to enter, though by the time we left it was beginning to fill up and sink into the sort of sensory chaos we have encountered everywhere in London. I was a bit too lethargic, a bit too worn down and unrestored, to make the most of the collection, but I took note of a few old favourites-A Man seated reading at a Table in a Lofty Room, The Execution of Lady Jane Grey. In a place so saturated with great works of art, maybe it is telling which ones manage to capture your attention above the rest. I have always liked the darker pictures, the fantastical ones.

After making our way around most of the free entry gallery, we exited and came to the sensible conclusion that we were going to need those jackets of ours after all. It was a bit of a detour back to Covent Garden, though one worth making given we ended up walking very far through chilly forest and parkland this afternoon. We were going to Highgate Cemetery, a suggestion made by Mum early in the planning days-it was up in the north, near Hampstead, and not so much frequented in the winter as a tourist destination. We fuelled up on falafel boxes from a local place and took the Northern line from Goodge St up to Archyway. These places were all unfamiliar to me in a way London had not been thus far, and it added to the sense of entering the fictional, haunted atmosphere that cemeteries usually possess.

I’m sorry, I ran out of the words to tell this story. I remember Highgate Cemetery—the grave of Karl Marx, the foxes, the moss and vines which grew all across the weathered stone and crept up the bodies of the bare trees—I remember. I can recall Hampstead Heath and the cold wind and the muddy road leading into the winter fair we didn’t take, and the walk down the hill to the train in the growing dark. There was dinner at a restaurant where they took mum’s dieteries so seriously they provided her with a carefully crossed-out menu, and one particular dish of grilled mackerel with chipotle romesco sauce which was one of the most delicious things I had ever tasted. I can remember others things and I can’t say them here.

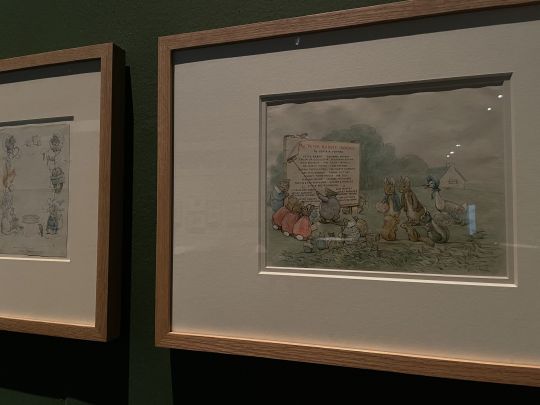

As this journal went on and time passed, my style became more constructed, less literal—I found myself going back to edit out lines too lurid or lyrical to immortalise in publication, as though the whole thing wasn’t its own kind of indulgent artifice. I was not writing what did happen but how it happened. What sounds and sights and plates of food and people revealed themselves to us, in a certain telescope lens which magnifies all things that the language of myth can construe, and the approximate order of their appearance based on the order of the photos in my phone camera roll. Regrets and weighty moments will be preserved without help, in the storerooms with all the other pictures; this is the art gallery, and now I have to end my curation here, avoid cluttering the walls with too much stuff before no one knows what to look at and ends up leaving with nothing.

Cezanne said: “Techniques are merely the means of making the public feel what we ourselves feel, and making us acceptable.”

I’ll see you soon.

0 notes

Text

london 20th december

Some ten days or so after we left London for the historic rues of Paris, and we’re here again, though the city is not exactly as it was before. The sun still rises late but the Christmas crowds in the centre of town have thickened, drawn in even more by the easing of the cold���no longer in the negatives, milder, even warm enough for us to walk around without our heavy coats. We set out this morning after a bit of unnecessary fussing about on my part, stopping at Monmouth Coffee Company up in the Seven Dials on our way for a hot drink.

With the typical flair of well-meaning inner elites, this shop serves all coffees in ceramic rather than disposable takeaway cups, so customers who cannot fit its cramped interior must hover on the pavement outside with their mugs, forced to slow down for a minute and exist there. Inside the cashiers cry out orders in a chaotic call-and-response with baristas always in motion; somehow no request is ever lost, from flat whites to cups of the filter coffee that drips through bespoke and no doubt biodegradable slips of paper in an endless lab experiment.

Unlike the other places we’ve chosen to visit earlier in the morning so far, the British Museum was already massively attended from the moment it opened. The lines for both pre-booked slots and the as-yet unticketed seemed to stretch into the hundreds. They were mostly families, mostly English—the little boy nearest us in the queue was proudly reciting knowledge of the museum’s Egyptian collections to his next of kin, so we prepared ourselves for some passionate competition in accessing all the best views. I had not been to the British Museum since I was seven and had no memory of the place, even its columned façade was novel to me, much less the huge stark-white spiralling entrance hall with rooms in every direction. The one thing I half-recalled from more than a decade ago was a case containing a menagerie of mummified animals and we sought this out first.

The Egyptian section actually wasn’t so bad at this hour, all outside predictors aside, so we got to have quite a good look around at this notorious collection before the rooms filled up. Notorious is perhaps a personal bias—there’s something unsettling in my eyes about too much of this ancient hoard, sarcophagi and the objects of sacred burial rites ripped from their resting places to be kept by a colonial legacy power rather than a country of origin. Cats, snakes, other small creatures are one thing, but the display of people’s corpses, people who were probably not very sympathetic or benevolent in life yet still, wanted to be buried and left there so they could enter the next life—I felt disturbed by the mummies, and not just that they were dead. It disturbed me how people gawked at them, and it disturbed me to think that this display was a mere fraction of what the museum possesses that it maybe shouldn’t, that others are wanting back.

After exhausting ourselves a bit wandering through the Greek, Roman, Assyrian, Islamic, Viking and ancient Anglo-Saxon rooms, we stopped off finally at the most awkward example of this archeological imperialism. The statues of the Parthenon, assembled headless and limbless in a cavernous exhibition hall, seemed to be begging at any given moment to be anywhere else. It was as if their display clung a point that most would consider to have been lost long ago when Truman and Stalin sat side by side as leaders of the world at Potsdam, and Attlee, so forgettable that I had to remind myself of his name, perched cheerily in the corner in the midst of British imperial decline. It’s a testament only to how far such a decline had to creep over and how far it must go still, that the statues were still there for us to see without mention of the controversy.

They were beautiful, rather eerie in a way that to me at least exceeded even the mummies. I think they could be haunted. The detail of the cloth and human form they embodied was extraordinary, and since I was too weary to read the signs and plaques which sat at their feet, I just stood and looked up at them instead. The far right end of the hall first, then I turned and walked the seventy-five metres worth of frieze to the other side, where I looked into the frothing mouths of stone horses forbidden to break free. Like the Cast Courts in the Victoria and Albert Museum, it was the magnitude of this exhibit that cemented its place as my favourite, cat-themed articles of Ancient Egypt aside. But I would rather have seen it in Athens, with a warm Greek summer sun streaking in, able to step outside and see the crumbling columns of its home waiting atop the distant hill.

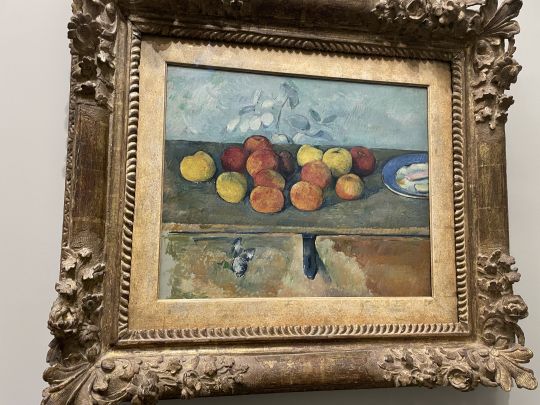

After the British Museum, we began on our way south back towards the Tate Modern we had promised to return to when we had the chance. We stopped in a sweet little laneway in Covent Garden for lunch from a cafe called Bibi’s Kitchen, where some serious-business young Turkish women served up bowls of the day’s offerings—a combination of grain salads, pickled cabbage, homemade hummus, so on. They were generous and delicious, popular with a local crowd on their lunch breaks. Refuelled we made it to the Tate Modern right on time for our two o’clock entrance to the exhibition of Cezanne. The collection traced his art from early studies to the last works of a man who felt death’s approach. Characteristically I liked these more morbid pictures most. There was a mourning expression to the skulls that stared the viewer down, and their bed of flowers was woven and artificial rather than living.

But I loved the bathers too, painted neither as corruptors nor objectifiable coquettes but merely people, people sitting and lying and standing. Cezanne’s world was a peaceful blue-yellow and invited visitors to pause at length to see five pictures of the same apples and jug aligned and not be bored. I had left my copy of Rilke at home but found I didn’t need it because the exhibition itself included the poet’s quotes in response to the art in large print on the walls, so clearly I am not the only one who thinks that he put it best.

There was a man visiting at the same time as us. He was tall in a black wool coat and brown pants, wearing glasses with a tortoiseshell frame. He was one of those people who carries a book around in his pocket wherever he goes—today it was something by Gabriel Marcia Marquez, though I couldn’t see the title. He had a little notebook in his hand and he was writing things down in it, copying quotes, and, I imagine, recording his thoughts. He would walk up to a painting, pause, and breathing heavily with his mouth open a crack, write in an aggressive burst, underscoring each last word with intense finality. I followed him around, obsessed and unnoticed. I was exterior to his trance and he never saw me. I loved Cezanne but somehow I will remember this stranger more.

Leaving the gallery we crossed at the Millenium Bridge and Mum took the lead, bringing us to the Inns of Court in the heart of Holborn, somewhere I had not known of before. It was almost silent in these little squares and streets—through the windows we saw a few clerks at work in the historic stone halls while one or two people hung around on the park benches outside. This was the most peace we’d encountered in all our time in London. The Christmas decorations were tamer and the cobblestones were littered with fallen leaves. Mum thought of visiting the Temple Church and so we went there, while there was still light in the day.

We were greeted inside this ancient house of Christ’s warriors by a very kindly old man, gentle and warm, who welcomed each individual group of visitors with the same passionate care. He offered us guiding maps of the church’s interior—the significant tombs, the bits of it lost in war and rebuilt. I felt it was almost the only church I’ve been in on this trip where some distant, perhaps violent but pure and earnest vein of Christianity has remained since long-lost times. It was not religious or ecclesiastic, it was holy, and honest enough to be the proud resting place of soldiers who killed in pursuit of their god. The old man showed us out the door and I wished him a Merry Christmas which is not so like me, but I was affected. We left this place behind in the hour of dusk and went home.

For dinner, we made our way over from our Covent Garden hotel to Chelsea a little earlier than usual, where we ate an incredible feast at Kutir. This was an Indian restaurant chosen under the circumstances of feeling, as delicious as all the food had been, that another night dining on the seasonally trendy squash, celeriac and beetroot at a modern European restaurant was an unbearable prospect. We needed something spiced and rich and hearty—we found it here. The interior of the small dining room, filling the ground floor of a corner Chelsea townhouse, was ornate and decorated in soothing warm tones. After some smaller dishes to start, Mum had brinjal salan—baby eggplants in a tasty peanut sauce—with a pot of dal on the side, while I opted for the classic chicken tikka masala. Its heat was offset by the lightness of a mango-chamomile cocktail and the delicate desserts that followed. The highlight, traditional Indian milk dumplings in a sticky, rose-flavoured syrup.

Since it had been an early booking, we still had a bit of evening time to work our way through. We occupied it by walking back to the hotel past many of the sights, now obscured in darkness, that we saw at the beginning in daylight, from a crowd. Along the fenceline of Buckingham Palace, via the outskirts of Picadilly, we arrived back in Covent Garden where the fuss never quite seems to quieten down, even on a Tuesday. My anticipation of the next day was coloured in conflicting ways by the knowledge that it would be the last. I wanted it to be a perfect end—this is always too much to ask for as a traveller. I was once again so tired I quickly crawled my way onto my sofabed in the hotel suite sitting room and fell asleep.

0 notes

Text

amsterdam-london 19th december

While today, bookmarked at each end with the ferrying of suitcases down hotel corridors, was labelled as a travel day on the handwritten plan which accompanied us throughout this trip, it also contained the purest stretch of Amsterdam tourism for us so far. Our Eurostar train returning to London did not depart until late in the evening—though we had to pack up our bags and bid a kind of farewell to our residency at The Hoxton, the city was still ours for a while longer. We began at the place whose grip on typical Amsterdam tourists is undeniably strongest: Van Stapele Koekmakerij, a tiny shop offering only one item. The freshly-baked dark chocolate cookie with a centre of melting white chocolate is available from ten o’clock until its source of dough is depleted for the day, and people line up on both sides of the street to acquire them. As we were waiting in the opening-hour queue, we saw the girls working for the shop come down the street bearing huge tubs of the raw dough, baked to serve within.

Eventually we made it to the front of the line and were able to enjoy a cookie each under the grey, rain-specking sky of the nearby square before a bookshop window. So began a morning of hunting down Amsterdam’s iconic gastronomical experiences, the ones that had alluded us so far with bitterballen and Hollandse Nieuwe ticked off my list. We started on a walk down towards De Pijp, across atmospheric misty canals which were thankfully no longer surrounded by streets of ice, but still quite cold. I admit to being very fond of a grey-skyed day; I remember my last day in Amsterdam three years ago was grey too, even though it was the middle of summer then. I took the opportunity to cement in my mind the vision of related yet unidentical houses, fraternal twins with consistently variable accent colours, heights and adornments. We followed the road past the great brick monolith of the old Heineken brewery into those flat streets unbroken by bodies of water.

About eleven-thirty we came upon the Albert Cuyp Market, a century-old street market with all the usual stalls and food trucks. We couldn’t possibly leave Amsterdam without trying some fresh stroopwafels, so we waited for a few minutes at Rudi’s Original Stroopwafels for our turn to be served by the enigmatic stroopwafel chef. Rudi—Ruud—and now his son and son-in-law, one of whom was at work today, have been running this little enterprise for nearly fifty years, serving what is said by many to be the best stroopwafel on the market. Ruud and his family preserve a tradition of thin spiced biscuits sandwiching a syrup filling, following the old recipe of Gouda. They earn their reputation.

Unlike the showy ones in the centre of town, which are perfect circles decorated with gaudy lollies and novelties, these stroopwafels were rustic, their caramel filling seeping out around rough edges after it was cooked and assembled from scratch before your eyes. No tacky flavours, only original and lightly chocolate-dipped varieties. The man behind the counter, who took his time taking and preparing each order with a friendly conversation about travel or the weather included free of charge, never multitasked for maximised profit and delivered a careful spiel about holding the hot stroopwafel properly flat to maintain structural integrity to each customer before they went on their way. An experience for tourists, perhaps, but a genuinely felt one, fuelled by earnest passion and the highest-quality ingredients. Van Wonderen Stroopwafels may boast a hundred thousand social media followers and the affection of the modern influencer, but it can’t hold a waffle iron to this un-meddled, crisp caramel-spice treat.

Our final stop on this thematic voyage, arrived at just after a midday opening which had already provided it with a decent queue, was Fabel Friet for some crispy high-class wedges of golden potato. This particular frites shop didn’t yet exist the last time I visited, representing something of an ascension from the mediocre mass-served versions on the main street that were most popular then. These ones came in little takeaway containers with a choice of toppings—both Mum and I accepted the standard recommendation of signature truffle mayonnaise and parmesan. Unsurprisingly delicious, though it would be difficult to get the combination of deep-fried potato, creamy sauce and salty cheese wrong, so destined do these components seem to be to appear in the same recyclable cardboard terrines. We could leave satisfied knowing that the most important cornerstones of any Amsterdam travel itinerary were now complete.

With still an afternoon of time to fill, we went back to the area around the Oude Kerk and stepped inside the mouthful of the Museum Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder, or, Our Lord in the Attic Museum. This was a preserved and recreated hidden Catholic church from the seventeenth-century period when the religion was not openly practicable, a once common occurrence in the hidden parts of wealthy Catholics’ houses where a small local community could gather to worship. An audio tour led us through the many rooms of the house, offering details of religious history and daily life at the time; some rooms were furnished, others displaying cases of broken crockery and kitchenware discovered in an archeological excavation. Up the narrow, uneven wooden stairs in the attic, as might have been predicted, was the church. It felt strangely spacious despite the cramping of pews, altar and galleries into the one attic floor. A screen showed a video of how the hidden pulpit unfolded in a flair of clever mechanisms from the wood beside the altar. There weren’t many people in the museum—from the street, you would hardly know it was there, just as the sorry merchant Catholics must have liked it some three hundred, four hundred years ago.

There was little time now, and we were tired, so we waited out the rest of the day in the buzzing hotel lounge with cups of tea to tide us over. The last notable sight we saw on our way was Amsterdam’s alleged smallest building, a mere sliver of brickwork in an alley that now hosts a tea shop in its tiny ground floor. But despite its narrow face, it bore all the same markers of the city—the hook over the highest window for delivering items of furniture and stock upstairs, affixed to a corniced pediment; the iron stitches holding it all together. In no way made remarkable amongst its congruous neighbours, except by its size.

Rather than repeat the fraught journey on foot with our suitcases that began our stay, we allowed a taxi to take us on the unavoidably roundabout route up to Centraal Station. As Eurostar travellers we were herded through brusque, no-nonsense security checks to be held in the pen a while, wincing at every diseased cough, sneeze and snort in the crowd. The British passport control agent who got me seemed to be either bored or suspicious of my being a human trafficking victim, as he has me stand there answering an array of interrogative questions. Eventually, well under the cover of night, we made it aboard and settled in for a long voyage by train. We ate simple supermarket to-go food for dinner on the way, not arriving in London until late on a carriage now half-empty from departures at previous stops. King’s Cross Station was very quiet and empty, the shops were closed.

We found a cab and asked the driver to bring us to Covent Garden, to the cobbled lane of Henrietta Street at its northern end. Under the Christmas lights this part of London was mostly as shut-up as the station had been, reduced to a late Monday night state of civility. The front desk of the Henrietta Hotel was watched over by a sweet young European man who showed us across the road to the rooms they keep in a charming townhouse there; we’re up on the fourth floor, sharing a large space with me on the completely bed-like sofabed and a glamorous bathroom between us. While Mum turned in for the night, I sat on the floor in front of my laptop and engaged in a focussed organising session. We have only two days in London before this trip ends, and holiday-planning—even last minute—my newly nurtured passion.

0 notes

Text

amsterdam 18th december

I had never been in this region of Europe during the winter before. Or, what seems the winter to me—the months that begin with the first of December and end with February, all solstices aside. Unlike Mum, who lived part of her life in London during an era when the kind of cold we encountered today would have been unthinkable, I could more easily rationalise the minus-five chill which welcomed us on the streets as we headed out for the morning. It occurred to me, looking at the number displayed on the weather app before my eyes, that this was something like the coldest weather I have lived in my whole life. I pulled a scarf up around my nose to face this freezing state of affairs until we reached the Rijksmuseum.

The museum is one of those places that everybody visits, maybe that’s why the only sensible time of day to visit is first thing in the morning, because as the day goes on the huge building nonetheless fills up and one is more likely to see the back of someone’s head than they are any actual pictures. Looking down at one of the printed maps in the pearly white entrance hall, it’s easy enough to believe you have something possibly manageable within an hour or two on your hands. But as we began to make our way around the circuit of the second-floor gallery, containing the great Dutch artworks and relics of the seventeenth century alone, we were quickly overwhelmed by the magnitude of the collection and its depth—every room, every object deserved at least its own half-hour, time we could afford only a fraction of under the pressure of our schedule and the drag of gallery fatigue.

In the seventeenth-century galleries, I loved the memento mori still lifes best. There were many of these paintings interspersed between piles of ripe fruit and unwilted flowers. Pictures of skulls and candles burning low—not incidental arrangements the artist could have the air of simply stumbling upon and capturing the light and colour of, rather an articulate message: remember you must die. Mum said she was most amazed by the Dutch masters’ manipulation of sun and fire, sources of light that bathed their subjects in a kind of animated realism. She was right when she suggested that only by looking at the art in person can it really be perceived and felt. I might’ve seen a bit too much of it on my previous visit to be as astounded as a person ought to be. But I was still captivated by the inky black seas upon which the people and objects floated, illuminated like they’d been brushed by the fingertips of King Midas but with a warmth beyond any piece of solid gold.

On the same floor was the Gallery of Honour, a great hall of alcoves containing the works of Rembrandt, Vermeer, many others. At one end we saw the progress made in restoring Rembrandt’s The Night Watch. This was a curious change from the time I first visited and named my journal after the painting’s Dutch moniker of De Natchwatch. Back then the museum was still in the process of researching and preparing for the monumental project of laying hands on such a significant work of art, now a completely new structure encased its canvas. After seeing so much the same on my return, this difference struck me as the morbid still lifes did—time moving forward, implacable.

We didn’t have much more time to explore the museum after that, as Camilla had made a booking for brunch at a nearby cafe for us to meet again with her and Rob and little Oscar. The best we could manage was a quick diversion into the nineteenth-century rooms on the floor below; more than the Van Goghs or the great Waterloo gallery I was glad to see again my favourite painting from when I visited before. Breitner’s The Singel Bridge at the Paleisstraat in Amsterdam was a familiar moment in time, captured and repeated. I hadn’t remembered it too particularly or where it was in the museum. Coming across it again, I was taken back to my old journal entries and the person I was then.

Leaving the Rijksmuseum behind, we walked about fifteen minutes up the street to the cafe, a Melbourne-like place where we sat for a happy hour or two with Camilla and Rob while Oscar waddled around the table legs and ate toddler-torn chunks of the house pita bread. On the way we crossed the bridge over Vondelpark, sunk beneath a layer of frost and less frequented by picnic-goers and cyclists than it was in my distant summer memory. My dish at the cafe, also ordered by Mum, was a tasty arrangement of halloumi and roast pumpkin and black beans, the sort of food we most love. The coffee order for the table comprised three flat whites for the adults, a fresh mint tea, and a babycino. At the end of the meal we watched Camilla and Rob ride off on their bikes with Oscar firmly strapped aboard—I was very sorry to see them go, but touched they made so much time to see us more than once during our brief stay in Amsterdam. Their kindness to me has been very great and I owe them.

I have been battling on very persistently so far this trip, but this was the moment at which it seemed to catch up with me. Though it was only early afternoon we returned to the hotel and it was there that I passed out into a state of atypical slumber—I never sleep during the day, this time I did, and I woke up to several unread text messages from Mum and a hazy disorientation. I turned on the little hotel room television to ground myself and switched to the final of the world cup, where France was playing Argentina. It was a good game, I think, though I don’t know much of the sport. Down in the restaurant-lounge on the ground floor where I went to meet Mum for a drink, the staff were subtly watching along on a screen behind the reception counter and ripples went across the room each time a penalty shoot resulted in a goal.

For dinner we walked to the very edge of central Amsterdam’s western islands, to a tiny collection of residential streets surrounded by canal. The restaurant I’d found was a small and quite new place called Barentz Restaurant and Bar, tucked away up there in the far reaches. Not many Amsterdamers were out tonight night in the cold—only two or three other tables were occupied this evening. The food here, prepared personally by the restaurant’s two owner-chefs and delivered by a charming waiter-barman, was delicious and comforting. The starter of roasted leek with miso was especially good, but my main dish, the meat of the day, was so incredibly tasty I feel that is what will linger in my memory most. Tender pink slices of bavette steak, dripping in rich umami sauce and served with mushroom and wilted greens, salty and rich but refined. Alongside a spoonful of crisp radicchio leaves and a sip of espresso martini and light wine, it was perfect. Mum’s dishes centered melting pumpkin ravioli and polenta, while for dessert we enjoyed a delicate chocolate cake with butterscotch and a serving of sweet, tangy curd with candied carrot.

On our way out the door after this wonderful dinner, the sweet young man running the front of house warned us to be careful out there with the frost and ice; we’d walked there from the hotel only two or three hours ago, so perhaps we thought we didn’t have too much to worry about. We were proven instantly wrong in this. A shocking amount of slippery sleet and frozen canal water now covered the pavements and roads. We were laughing as we tried to walk towards home but only succeeded at ice skating—or falling in Mum’s case, not very hard but still decidedly onto the cobblestones in the middle of the silent street. I gave up attempting to lift my feet off the ground and began to shuffle instead, scraping the soles of my battered canvas sneakers forward one after the other. It was good fun and highly unsustainable. We were not going to make it the distance back to the hotel any time soon.

Luckily for us, an internet connection makes these things much easier. I found that there was a bus stop on the nearest main road where we could get a bus to Centraal Station and then a tram to the stop just around the corner from our hotel. The bus was pretty crowded, clearly the ice-rink streets were not a popular place for anyone to be strolling about tonight. With gratitude and admiration towards our bus driver braving the slippery roads to bring us to safety, we got off in the centre of town and soon made it to our beds unharmed. Today had been a little fraught around the edges for me, with fatigue and a feeling of clutter, but it ended so happily. My last night in Amsterdam for a length of time I wouldn’t be able to predict—of course bittersweet, but the bitterness subdued by the taste of moreish hot food and laughter at the callous jests of nature as we skated along, clutching at railings and parked cars for support.

0 notes

Text

amsterdam 17th december

Today was Saturday, market day. One of my clearest memories of Amsterdam from age sixteen was wandering between the stalls of the organic farmers market in Noordermarkt with Camilla, buying fresh produce for our dinner that night. It was a part of the city I wanted to experience again, so we left on foot early for the northern neighbourhood of central Amsterdam. The market comprised the usual fare of fruit and vegetables, cheese, meat and bread; I was particularly taken with the stall selling an endless variety of mushrooms from the familiar white button or portobello to the truly alien rare types. Neither of us had eaten a proper breakfast in expectation of getting something there, so we surveyed our options.

In the square where the farmers market takes root we were tempted in the door of Winkel 43, an unassuming café I had known about since my first visit that is famous for its apple pies. So popular are the generous, caramelised slices of this dessert that on market days such as today the café doesn’t even serve its usual food menu, and the workers were in a constant process of cutting up enormous freshly-baked pies and plating them up to be served. We each got a slice—I enjoyed mine with their offering of whipped cream, and fresh mint tea to drink. The pie was incredible, not dry or cakey but rich and the perfect combination of melting apples and crisp warm pastry. Buoyed by this new culinary highlight in our lives, we walked through the rest of the Noordermarkt to see the rest of the typical food, clothing and bric-a-brac stalls, the lunch stands and trucks just beginning to set up for the day.

I had planned to take us to Tony’s Chocolonely after the market, but it was only half past ten and the less well-known and touristy location up in Westerpark didn’t open until midday. Instead we returned to the city centre through the Jordaan neighbourhood and along Haarlemmerdijk where we came upon the main Tony’s Chocolonely Super Store, remarkably devoid of the awesome queue which we had seen snaking around the street outside the day before. It was eleven or eleven-thirty then, in another hour or two the line would be back. The line is not for the store itself, perhaps because at least half the full range of Tony’s flavour is available at every supermarket in the Netherlands, but for the ‘design your own Tony’s’ experience’ that draws hundreds of participants each day.

Since there was no queue at all, I claimed one of the screens before the chocolate-kitchen window and designed my Tony’s: dark chocolate, pretzel pieces, raspberry, red and white wrapper since black was not one of the options. I arrived at this combination after many minutes of troubled paralysis before the list of possibilities; I realised most of my ideas were recreating the flavour combinations of Tony’s bars that already exist, so I decided to go for something ninety per cent random. I put in my phone number to be notified when my custom chocolate bar was ready for collection and we headed back up from the colourful basement shop into the cold.

A bit short on shared activities for now, Mum and I went our separate ways and I pottered around the streets until I received the message that my custom chocolate bar was ready back at Tony’s. The tourist swarm had descended by then—I had to fight my way through the mob to make it to the front of the store, where I witnessed the shameless seagull-like behaviour of the people attempting to snatch handfuls of free samples until the harangued man behind the counter took it out of their reach. From there I crossed over to Centraal Station and, after a brief detour to the supermarket where I rescued someone’s forgotten credit card from the self-serve checkout, I took the north-south metro down to Europaplein.

I remembered the station. It’s nothing like London’s Underground, or Paris’ metro, which are cramped and often dirty—it’s a vast platform, dark grey, clean, not far below the earth. I took the north-south train from here into the city centre when I was staying with Camilla and Rob the first time. Above the station is an expansive, comfortably bleak square and convention centre, today occupied by a winter wonderland funfair with rides and a ticketed entrance. It was clear the cold hadn’t put off any local families from attending this seasonal event, but I passed it by, and went around the corner to de winkel van nijntje (’Miffy’s Shop’) which, a bit like the Moomin Shop, sells every product imaginable in a Miffy bunny rabbit version.

I have fond childhood memories of Miffy, and the shop was so charming with its Miffy Christmas window display and its staff of friendly young people—about my age, running a playlist of popular indie music over the speakers. I ended up buying a soft, classic white Miffy plush toy for myself as a souvenir, and a little crocheted Miffy charm wearing a blue dress for my best friend Madeleine, who loves Miffy and owns many iterations of her in different forms. Before I went on my way back towards the centre of town I sat for a while in a nice café opposite Europaplein, where I drank my coffee and ate my complimentary bite-sized spice biscuit at the window and watched the fairground Ferris wheel turn in the distance.

This was a neighbourhood I knew better than most of the inner streets from being there before, actually, and it was with half-clarified nostalgia that I followed the wide Ferdinand Bolstraat across the canal and into De Pijp. I walked past an Albert Heijn supermarket and there on the street corner stopped dead—I was looking at a white-painted shop a few metres across plonked in the middle of the pavement; I remembered it. Dutch flags hung over the entrance of the fish stand, a permanent structure with the air of a market stall, unassuming and unnamed. This shop does not appear on any online maps or in search results. It was only by the look of it, there in the flesh, that I knew what it was. Camilla and Rob took me there to try Hollandse Nieuwe—Dutch soused raw herring, traditionally served with diced raw onion and slices of pickle—when I stayed with them. There’s a photo of me standing in front of the same glass refrigerated case, under the same LED panel lights, laughing next to Rob with the paper plate of fish in my hands.

It took a long time to summon up the courage to go in alone. I nervously asked the man running the shop for the herring dish, though he explained to me that his card reader was broken and he could only accept cash. I didn’t have any but I knew I was going to let nothing stand in my way now. I promised to be back in a minute and rushed across to the supermarket to withdraw twenty euros. Then I hovered before the counter while he prepared my herring fresh, slicing everything up and adorning it with one of the same tiny Dutch flag toothpicks that I had eaten with three years ago. I thanked him in earnest and ignored the embarrassment of taking photos out on the street in front of locals like the tourist I was. It meant something very heavy to me to have this moment again. And I hadn’t meant for it to happen, unlike almost every other detail of this trip which I have planned meticulously, accounting for every destination and event along the way. In its obscurity I had no method of finding the same fish stand again; I hadn’t even considered it, I found myself at its door of PVC strip curtain by accident alone.

The herring itself was delicious. The raw fish of this dish is fresh and delicate in flavour, paired perfectly with sharp onions and pickles. Perhaps it might be offputting to some. It’s not to me. I finished it quickly and cleaned off the toothpick so I could keep the little flag in my pocket as a memento.

I made it back to the hotel mid-late afternoon and promptly collapsed on my shoebox bed for a rest. For dinner I had booked us a table at Restaurant Entrepot, a fine dining sort of place up on the Entrepotdok canal of reappropriated warehouses. We speed-walked there, mistakenly for stretches along the sardine-tin streets of the central tourist district—I’m afraid I rather put Mum through it getting there on time, but we did. The restaurant was an expansive single dining room inside, very simple and chic, with kitchen and bar exposed. The very kind waitress brought us their daily menu of dishes constructed with all the best seasonal produce of the Netherlands and told us when the wine we’d picked a bit at random was probably not going to be to our tastes. We opted for three courses a la carte.

My first plate, a cold starter, was the most surprising dish of the night to me. It was pearly strips of squid served on a bed of burrata with a garnish of seeds. The squid was almost a little bit like al dente pasta presented with cold creamy cheese sauce, hard to describe without rendering the image somewhat disturbing, but I thought it was incredibly tasty. Next I ate a hot starter dish of roast pumpkin and mushroom, then a main of crisp-skinned, tender-fleshed skate wing; the restaurant served their remarkable food along with a plate of crusty brown bread. Mum and I shared a sweet potato dessert of elegant textures and subtle sugariness. Like everything else we had eaten there, the flavours and form were so precise in a way that was neither overdone nor left unappetizing by pretentious service. It was good food.

We walked back to the hotel around the eastern curve of inner Amsterdam rather than cutting across the middle. We saw Centraal Station and the great towering Christmas tree of Dam Square outside the department store glittering in the night. I dislike using the word magical—I don’t think I felt an awe beyond human nature in view of the lights, as we skirted there around patches of frost and ice forming in the wake of a new cold snap in the city; nothing was inexplicable, I was trying not to forget anything about it because it all meant something to me.

0 notes

Text

amsterdam 16th december

This morning I woke for the first time in my shoebo—that is the name the hotel affectionately gives to my size of room, which is just large enough to comfortably contain its desk, cabinet and single bed. With the curtains drawn it is dark inside even when the sun has risen, and no natural light penetrates the small tiled washroom adjoining it. As usual I’ve somehow managed to litter the contents of half my suitcase across the wood-board floor in the space of a day, so I hang the do not disturb sign from the door handle on my way out. For four euros at the hotel they will leave a small paper bag of breakfast—muesli bar, bit of fruit—on a hook outside your room, waiting for you when you get up.

We only had to round one corner and cross the canal to reach our first destination of the day’s itinerary in Dam Square, where the Royal Palace of the Netherlands sat catching the first rays of sunshine in a near-silent city centre. This was a much quieter state than I remembered Amsterdam’s tourist heart being in the height of summer, but the buildings were the same—I remembered sitting around in just about the same spot waiting in the same way for the palace to open its doors at ten o’clock for visitors. The only people besides ourselves hovering before the entrance were a few other over-enthusiastic sightseers and an excursion group of high school students whose attention was not very focused. We collected our audioguides and headed into the public rooms to start our tour.

It was all familiar to me from the last time I’d been—the palace’s history as a pre-Napoleonic era royalty town hall, the relics of Dutch trade in the form of half-accurate marble maps in the floor, the halls of ornate statue motifs. What had changed was the palace’s sense of its own golden age, an age not rendered so golden for the benefit of tourists anymore and unmasked by the post-colonial. Because the buried Dutch plundering of the world emerges not only through the columns of monkeys and exotic fish and other appropriated things, but by the presence of the stone in the first place—the obscene wealth, and how it was made. Every symbolic statue contributed its own meaning to the mythos; I liked the decrepit skeleton of Time best, or bare-breasted Artemis, standing over her quarry of fish, freshly hunted for a nautical society.

Between the palace and lunch we visited a few other places on my list, beginning with Begijnhof, a tiny historic religious community for women walled off in the heart of tourist Amsterdam. Its former inhabitants were not nuns but they were known for their little chapel and their good deeds—today, still only women live within the houses surrounding the green square. As a visitor one can have a look around the garden and inside the chapel, while the rest is reserved for present-day residents. This was one of our first looks into the religious past of Amsterdam, a history of revolt and reformation and other things more recent, and more terrible.

After a quick walk around the American Book Centre, probably the most impressive and extensive English-language bookstore I have ever visited, we bought fresh sandwiches from a local chain food store and sat over the canal to eat. Mine was on brown bread, which they do much better here in Europe than they do at home, with jackfruit, avocado and vegan sriracha mayo. It tasted like being on Brunswick St or within the wilds of a Collingwood hipster cafe, exactly what I have always meant about Amsterdam being so like Melbourne in some ways. Also as in Melbourne the young people in this city love queuing up for super-trend food opportunities. I found I was already pointing out to Mum one of the latest viral cafes or restaurants on every second corner. So we left the busier part of town and went east, by the narrow bridge and the Netherlands branch of the Hermitage, facing the wide grey Amstel canal.

We walked past the National Holocaust Names Memorial on our way.

Part of this trip for me, particularly now in Amsterdam, has been trying to do things I missed out on before, go places I haven’t been. The De Plantage neighbourhood is an island of green surrounded by canals and streetscape, here we visited the Hortus Botanicus, a doll-sized botanic garden with greenhouses and its own cafe. We went from freezing European winter to the heat and humidity of the tropics in seconds as we entered glass halls containing reconstructed rainforests and collections of palm trees. Precarious iron spiral staircases led up to bridges suspended at ceiling height. The smaller greenhouses were home to colonies of butterflies, the creatures left lethargic by the wintery day. We saw a robin redbreast in the bushes outside as though we had stumbled into a secret garden—the key to the gate had been the digital ticket on my phone.

The exterior gardens were just as interesting as the greenhouses, though distinctly colder, and some parts were buried in a layer of frost. Others had varying ground covers of orange and brown and vivid green, under trees and shrubs in turn gone bare or still weighed down by their leaves. It was the wilder sort of garden, left to pursue its own interests, except for in the parts of the park restored to a version of its seventeenth-century existence as a repository of medical plants. In parts of the hedge-lined semicircle garden were pools home to aquatic plants—these were frozen over, as was the large pond, with a layer of ice so thick it looked like it had formed over many days. Even in the late autumn chill the Hortus was a beautiful place and the frost had far from devastated its charm; I think it added to it.

As we walked back towards our hotel, cutting through the centre of town rather than trailing through the outer streets, we noticed how much the city’s tourist community had grown in the space of a day. Plane loads of the populist young English had arrived for the weekend, and passing through bits of the Red Lights District we saw some of the crasser types already wandering about on their way to poor life decisions. We stopped to look inside the oldest building in Amsterdam, the Oude Kerk. This church, boldly facing the dormant walls of adult entertainment, was cavernous within. It was stripped of former glory during the Reformation, left bare but for a few patches of paint on the roof that the angry mobs had been unable to reach. The bleak interior plays host to art exhibitions in the modern day and we spent some time exploring the current installation—a collection of sculptures, Garden of Scars, by artist Ibrahim Mahama. Under our feet were hundreds of tombstones. They made up the entire worn-down floor.

Tonight we were kindly invited by our Amsterdam friends Camilla and Rob to come to their house to have dinner and to hang out with their son Oscar, who was only a small baby when we saw him last. Having picked up a bottle from a local wine shop, we boarded the tram at Leidseplein and travelled down through De Pijp to reach their home. It reminded me so much of staying with them in a spare bedroom three years ago and Camilla made us a really delicious dinner of vegetarian lasagna and fruit crumble for dessert. We made plans to meet again on Sunday, before Mum and I had to leave for London once more. I realised how much I had missed them and this city where I first really came to know them in a different era for us both—we left not too late and took the tram home again, deposited less than five minutes from our door where the boorish Friday night throng could not reach us.

0 notes

Text

paris-amsterdam 15th december

The arrival of this morning brought with it our departure from Paris, with a midday train from Gare du Nord set to take us north across borders to Amsterdam’s city centre. Downstairs I came for the hotel’s breakfast and had two miniature viennoiseries—pain au chocolat and pain au raisin—and a piece of crusty baguette with cheese. They baked the pastries fresh there in the oven behind the buffet counter, still crisp and warm by the time they reached the serving platter. My cup of tea had a subtle, unsweet flavour of salted caramel.

Checking out and leaving our bags at the hotel, we went on one final mission to see Paris before it was time to say goodbye. We walked not very far to the Jardin de Luxembourg, a favourite of Audrey Hepburn’s, where we saw the guard of sculpted queens and duchesses watching over their domain. The trees in the avenue, like in the Palais-Royale, were completely bare, stripped back to their charcoal trunks. On our way back to the hotel we stopped to see the Église Saint-Sulpice and buy takeaway coffees, reluctant to leave with any time wasted. The kindness and warmth of this city have struck me more than I expected to feel from somewhere notorious for an unwelcoming attitude to outsiders. As we were dragging our bags down the street to the metro station, a tender middle-aged woman who worked at the hotel came sprinting after us to insist we take a free tote bag as a parting gift; this same woman had embraced me tightly earlier in the day, and I wish I knew her name, but I am happy just to remember her face and her French accent when she hugged me and spoke in my ear.

We were well on time to Gare du Nord for our scheduled departure, though unfortunately our train was not, so we ended up standing for a long while on the platform getting chilly feet. Eventually they opened the gates and allowed the flood of bored or delay-panicked travellers through, with none of the stringent security which had governed the Eurostar crossing. In fact once there was actually a train for us to go aboard, it was a very easy journey, and along the way we were able to see glimpses of Brussels and the frosted countryside of western Europe beyond our window. We ate a lunch of boxed salads we had bought at the Gare du Nord’s Monoprix to-go. In mine were leafy greens, lentils, smoked salmon, crisp stems of samphire.

It was about a three-hour trip to Amsterdam by train and arriving at Centraal Station I felt the opposite kind of delight to what I’d known in Paris—the comfort of familiarity. Three years ago I had come here as a very different person, now I was back and the city was just the same. Perhaps a bit foolishly I guided us onto the tram to get to our hotel, a more convenient idea in theory than in practice. Mum had the worst of it, trying to maneuver our wheeled bag along the cobblestones, up and down over canal bridges, through the tides of cyclists. The final straw was the canal-facing street where the hotel was located not even really having a footpath at all, just a strip of uneven curb. We agreed to take a taxi on the way back.

We’re staying at The Hoxton in Amsterdam’s city centre, just around the corner from Dam Square and the Royal Palace. This was an area I visited a lot when I came aged sixteen and I remembered it well, in a way better than I did the London I had been to on more occasions. It’s easy to feel at home here, in a city very like Melbourne in many ways, but on such a small scale that you can grasp something of its entirety in just two hands. We ventured out into the evening and explored some of the nearby shopping streets, which were decorated beautifully for Christmas—better than London and Paris combined. Rather than leaves the trees supported a canopy of fairy lights and everything glimmered in the traditional hues of red, green and gold. What we failed at was finding anywhere last-minute but satisfying to eat, and after a long and rather trying day that wasn’t helping anyone’s sense of equilibrium.

It’d been a bit crowded and noisy in the restaurant below the hotel when we’d been down earlier, but by now it wasn’t so bad and we accepted this as probably the easiest option to ensure we were actually fed. I was excited enough that they took their cocktails seriously and had pages of interesting combinations; I ended up trying their signature honey-flavoured cocktail to begin and a sweet Frangelico-nutmeg combination as my dessert. While Mum had a veggie burger for her meal, I decided to get ahead on revisiting old favourites of the Netherlands and ordered bitterballen. These are a sort of meatball or croquette, bites of rich meaty gravy contained within crispy fried shells. They came alongside a generous pot of hot Dutch mustard, so sharp with horseradish it burned a bit to eat. They were really tasty, as I remembered, and I felt happy that I was back.

0 notes

Text

paris 14th december

Today it snowed. We woke to find a fine layer of frosty white on the rooftops and gardens beds, still coming down in occasional flurries throughout the early hours of the morning. It wasn’t much, but it was new to me—in the courtyards of the Louvre I stopped to scrape a small handful from the edge of a fountain basin and form it into an imperfect sphere. I threw my first snowball as we made our way towards the Jardin des Tuileries, also blanketed in bleak white except for the paths that had been carved through to the gravel underneath. We had taken the metro to Pont Neuf and walked along the Seine to this precinct of art, where we called not on the coveted and crowded work of da Vinci but that of Monet, hanging close by the Louvre in the Musée de l'Orangerie. In the Jardin des Tuileries parts of the little lakes and fountains were frozen over, and the seagulls perched atop the ice like it was land.

The gallery housing Monet’s waterlilies was still almost quiet when we arrived for our early slot, though it was filling quickly with people seeking a photo opportunity with the magnificent paintings. In two large oval rooms hang several great curved canvases—the waterlilies, sometimes in seas of deep indigo, sometimes set ablaze by fiery sunlight, in places interrupted by spiny and twisted tree trunks casting a shadow on the lake. Simply sitting on one of the central benches, we felt the meditative aspect of this installation intended by the artist himself, the awareness of light and air and water emerging from impressionist brushwork.

Although there was supposed to be a rule of silence in the gallery, this was not much observed by tourists, nor were the unspoken laws of tastefulness in the pursuit of taking pictures with the artwork. It was a genuine case study of ego as people squabbled over the best sections of canvas for backdrops and left the room without looking at much more than the camera lens pointing towards them. But the waterlilies still amazed us and brought us, despite the interruptions of socially unaware or concerningly coughing people, to their silent banks, where one imagined a cool breeze might blow.

Downstairs in the Musée de l'Orangerie, where the mob was far more civilised, we saw works of other modern masters including Picasso, Matisse, Cezanne. In front of the Cezanne I read a few pages of the book I have been carrying with me—Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters on Cézanne, which I acquired in the Marylebone Daunt Books whilst we were still in London. Rilke is my favourite poet and writer; I chose the collection because I had not seen it elsewhere before. Like Rilke in 1907 I stood in a Paris gallery before a painting of apples on a table, positioned at slight impossible angle to accentuate their realness, and I’m sure we felt very different things, but I understood him when he wrote of Cezanne that he turned to nature and knew how to swallow back his love for every apple and put it to rest in the painted apple forever.

Escaping just ahead of the masses we took the metro from Concorde up to Villiers, to a small shop called Pâtissiere Pages Blanches that sells Japanese-French pâtisserie. There we shared a lemon tart made of short, biscuit-like pastry and sharp curd, decorated with tiny meringue petals to imitate a flower. Just around the corner from this precious dessert we visited the site of the Cimetière des Errancis, where 1119 headless bodies were once buried during the Reign of Terror in revolutionary France. The people were guillotined at the Place de la Revolution and entombed there together—Robespierre was one of them—now, nothing more than a plaque on a wall remains to remember the grave.

Keeping to the 8th arrondissement, we strolled through Parc Monceau down the street from this pâtissiere and plaque, which I think might my favourite park we have visited so far, decorated at precise random with bits of sculpture and stone. A mother paid for her child to ride the merry-go-round and its fairground music floated in the background as we stood on the bridge overlooking a little creek and lake of willow trees. Another woman sobbed violently, passing by us into the park as we were going out, overcome by an unknown grief.

These walks through the city have revealed so much of Paris to me that I did not conceive of before—its contradiction, as a place of people who sit for a long time with their lunch but who are always in a hurry on the train, and smoke cigarettes excessively while a pharmacy sits on every street corner, for their health. There is a new Paris, a young and different one, coming to life in bursts throughout its many arrondissements, but there are still the streets of fruit shops, boucheries and boulangeries, terraced bistros, and the tired or gaunt French, shoving their way through manual metro barricades and drinking wine together—that Paris remains. There is such good fresh food everywhere, there are so many identical apartment buildings everywhere, and if you try your hardest to speak French to a Parisian rather than force them into your own foreign tongue, they will probably speak it back.

Having eaten hot wraps for lunch in a dining room full of office workers at the nearest Pret a Manger, we went back to the central shopping area and had a poke around the Printemps department store. We visited l'église de la Madeleine although its exterior is currently obscured by advert-clad scaffolding—the inside is still astonishing, a cavernous space housing great domes and statues lit from above. In its heart hung an art installation of glass teardrops which caught and refracted the light like electric bulbs. I’ve seen many remarkable churches, but this was one of the best. I liked that it had so few windows to allow the natural light in, it felt like a world of its own.

We were tiring at this point but far from done, and took the metro back across the Seine to Invalides to see Napoleon’s tomb. I actually had very few concrete expectations about what a monument to such a man might look like, so I was stunned by the imperial ostentation of the dome that holds the coffin. Statues of Napoleon in the form of a Roman emperor doing godlike acts surround his own grave, accompanied by glowing descriptions of achievement. All of this composed long after his death in shame and miserable exile, for the man who almost ruled half the world. There were other burials in the Places des Invalides dome but they could not live up much to the shocking excess of Napoleon’s memorial.

Here was where we parted ways for the afternoon and Mum went to see more of the Rive Gauche on her own and I went to seek out Kick Café, a little café centred around K-pop music. I found it and explained my presence in very poor French to the girl about my age in charge that evening. I bought a coffee and their self-published recipe book of K-pop group inspired drinks, because it seemed like a sweet memento. Surrounded by these local young people I felt I recognised Paris as a city of people not so different from myself for the first time, not just a city of buildings and the characters who live in them. I came back to our hotel in the dark, seeing the young men begin to gather at bars and bistros to watch the World Cup semi-finals on my way.

We ate dinner at a restaurant called Libertino, a very trendy young Italian place that played Michael Jackson and Britney on the speakers and had a bathroom plastered with semi-ironic Rod Stewart posters. We were sat at the bar in the basement salon, where we could watch novelty cocktails be made and had a good view of the artfully maximalist decor. To start we shared an entree of a plump creamy burrata with pasta for mains—pappardelle with lamb ragu for me and veggie-filled tortellini alla ribollita for Mum. The pasta was especially delicious, so freshly made and the sauces so rich in flavour. Our dessert of tiramisu was served up to us at the table from a huge cocoa-dusted tray by a charming man who offered us an extra little scoop, though I expect he does that for all the girls.

We could have gone directly home, but the raucous cries emanating from every bistro with a public television that we passed kept us engaged. Because it was France playing Morocco in that semi-final, and the same sense of desperation I felt in the air around Eygalières four years ago re-established itself in the heart of a sprawling metropolis. The terrace of one restaurant had spilled out onto the road, collecting passers-by as the last fifteen minutes of the match approached. I have never cared much for sport but I love the energy and there was one young man here, who, blonde-haired with musketeerish facial hair, pulled his friends out into the street when France won and danced around singing allez, allez-les-bleus. At the Opéra crossroads, the cars were honking their horns in a chorus of infectious love for la patrie.

0 notes

Text

paris 13th december

We began our day today with an unhurried stroll down from Les Gobelins to the Seine, passing by a few noteworthy sights including the lesser-known Arènes de Lutèce not far from our hotel. These ancient Roman remains of an arena where gladiatorial combats occurred in the first century now make up a kind of public park, a place where boys might play soccer in a less bleak season. Further down the road we saw Notre Dame, by daylight for the first time, in similar states of ruin with a girdle of scaffolding all around. After admiring these ecclesiastic bones from across the water for a while, we went down the bank to Saint-Michel for the metro.

I didn’t remember visiting Sacré-Cœur the last time I was in Paris, aged seven, though there was something familiar in the grey, leaf-strewn steps that extended upwards at an increasingly painful incline. When we reached the top of the escalade it became clear we weren’t the only ones risking agonised limbs for the view of the city—this was the first proper tourist scene we had come across, complete with a hundred shuttering smartphone cameras and the calls of street-sellers promoting their cheap souvenirs. The great ivory cathedral was beautiful to observe from the outside but didn’t tempt us to queue for a glimpse of the interior, so we left this lookout over Paris’ smoggy skyline and its occupying mob behind.

We descended just in time to secure an early lunchtime table at The Hardware Société, situated along one of the streets just below the Sacré-Cœur. This unlikely iteration of the Melbourne cafe culture classic abroad was mostly chosen so Mum could have a chance at a real coffee, which the French don’t do. It was odd to walk into a cafe in Paris and be addressed in English by the middle-aged Australian man managing the pass, as though we had teleported to the tram tracks and sunnier streets of Brunswick, or North Fitzroy. The only hint of the Parisian was in the fried brioche, souffle and tuna millefeuille which balanced out the Melbournian brunch menu. I had their baked tofu, a vegan dish of soft tofu pieces in a ramekin of sweet pumpkin puree and cashew cream. It was something like a soup in effect, deeply comforting on a cold day.

I cast aside the reassurance of this anglophone, known environment by taking the opportunity while waiting for Mum outside the cafe to call up a restaurant about dinner—a Morrocan place, Le Sirocco, across the road from our hotel. The man on the phone got a little fed up with my half-articulated French at some point, but I was glad I at least tried. So far, Parisian waiters have failed in every way to live up to their reputation of haughtiness; perhaps we’ve just been going to the right places, or perhaps we aren’t loud and American enough to attract much ire. Each interaction has been so generally pleasant, almost too much so. It feels conspiratorial.

Next we visited the Cemetery of Montmartre, discovered at the end of a winding street of expensive shops and expensive homes that wore a coat of fallen plane tree leaves. Though we failed to find any of the cemetery’s notable graves, the general aura, perfected by the cawing of the atmospheric crows we could only assume to be paid actors. Many of the graves, forgotten or heirless, were crumbling where they stood. One particular headstone deposited on the main avenue between the grand funeral chapels and family vaults was folded completely in two, its lettering eroded and iron fence overgrown with moss. There was almost nobody about except for us and the birds and the groundskeeper watching at the cemetery gate.

From there we made our way through the tawdry tourist area past the Moulin Rouge down to the quieter Rue des Martyrs, where we came to rest on a wooden bench in the square. A small merry-go-round called Le Lutin lay dormant in the cobblestone-floored forest of lampposts and Christmas trees—here we ate freshly baked rugelach from a nearby Levantine bakery. These small crescents of pastry were sweetened by a cinnamon-chocolate filling and barely survived long enough to attract the attention of local pigeons before they were gone.

Our sightseeing continued in the Galeries Lafayette, a grand department store whose central dome enclosed an enormous Christmas tree decoration. Then the Palais Garnier across the road, this time from within, with its extravagant ceilings and overwhelming scale. It was crowded with people battling for the best angles for their selfies, though this state of social chaos did not detract from the opera palace’s magnificence, which announced itself above every staircase and at every turn. There are few places, even the palaces of divine right kings, that have so little restraint. The only ungilded stretches of wall were given over instead to mirrors which reflected back the glowing excess of the rest of the room.

Having made it back to our hotel for a short rest, we had only to cross to the other side of the little alleyway to make our dinner reservation at the Morrocan restaurant. This meal, served to us in a softly-lit dining room from clay tagines burning to the touch, was one of the best so far. We began sharing the vegetarian assiette, a collection of small salads and dips and crisp filled savoury pastry. My main was the lamb tagine with caramelised carrot and plump apricots, sweet and rich flavours complimenting meat which was so tender it fell from the bone. Mum’s vegetarian tagine was equally remarkable; we completed the evening with a crème brûlée crusted in biscuity semolina and honey-butter-soaked baghrir. My cup of fresh mint tea was poured from high above by the practiced hand of the younger waiter. We weren’t offended when the same waiter was forced to prod us out the door to make room for the next sitting of diners, gathered in anticipation at the bar. Better more people get to eat such good food, and sooner, than less.

0 notes

Text

paris 12th december

Although it was mid-morning by the time we managed to make it out the door of the hotel this morning, it was still freezing cold. I have already been wearing extra thermals under my clothes for the past week or two, and today before we left properly Mum went to buy some more of her own. It was all that was keeping us safe from the trenchant chill inhabiting the streets of Paris as we set out for what was soon to be sidetracked tour of French revolutionary points of interest. Of course, very little of the revolution’s Paris still exists today—it was torn down or built over many years ago to make room for beautiful Haussmannian apartments and gilded monuments to the Empire. The city of the sans-culottes whose fever brought madness to Robespierre and a first taste of victory to Napoleon exists more in written history than it does in stone.

Still, we began our walk by crossing the Seine at Place de la Bastille and followed it westwards until we came into the area of the Marais. Mum took on the mantle of guide for long enough to take us through the quiet shopping streets to the Place des Vosges. It seemed so silent, we wondered where all the tourists could possibly be. Within the fence of the iconic park there were icicles hanging from the mouths of the fountain’s lions, transforming them into lopsided sabre-tooth cats.

It was as we were making our way back from this peaceful enclosed reserve to the busier Rue de Rivoli that we realised we were coincidentally near Paris’ iconic falafel shop L’As du Fallafel, and it was close enough to lunchtime to make it an opportunity worth snatching up while the line was not too forbidding. The soft pita comes with falafels and salad and smoky roast eggplant drenched in delicious sauce, easily fulfilling its high promise. We ate as we walked, ending up at the astonishing ornate front of the Hôtel de Ville. Rather than mobs of Third Estate women preparing to march on the king at Versailles or the menu peuple presenting their petitions to the city who I learned of in my revolutionary studies, the square today was occupied by a pretty Christmas garden and market stalls. Having fallen a little behind schedule, it was here that we forsook the historical tour and boarded the metro going north towards our afternoon activity.

At two o’clock, right on time, we arrived at the Musée Jacquemart-André, not far from the Champs-Élysées. Like the Wallace Collection in London this museum was formed from a private collection—a couple, in the nineteenth century, whose love of art led them to amass a remarkable gallery of paintings and artefacts. They loved the art and history of Italy the best, and much of the collection comprises renaissance frescos, church carvings and depictions of the holy mother and child. The mansion they built to display their prized objects was beautiful enough in itself, and barely frequented by tourists except for us two. Compared to the other more frenetic galleries that Paris has on offer, where the impenetrability of the crowd might make it near impossible to see more than two square inches of a picture at once, it felt like a worthy use of time.

In the museum’s temporary exhibit was a collection of paintings by Fuseli, whose name I knew but whose art I would not have been able to place. These dark and fantastical works are very unique in style—disturbed and neurotic and sensational, in a way one rarely expects to see from his era. The exhibition centred around his obsession with narrative, whether it was Shakespeare’s theatre or spectacular Norse myth, and the psychological, in the form of the dream, the hallucination, the desire. As much as I loved the thespian allure and fantasy of his Shakespeare paintings, his piece entitled The Shepherd’s Dream, the last work shown, was my favourite. There was a loveable horror to how every corner of this painting revealed a new twisted fairytale creature—some pixie or spirit or grinning gremlin, corrupting the shepherd’s peaceful sleep. Over the course of the gallery, the enigmatic Fuseli appeared piece by piece; one wasn’t sure what to make of him, except that perhaps only a true mad genius could have spawned such gruesomely brilliant pictures.

After the museum we had a little time to spare before the next booking I had made, so we strolled up the road to see the Arc du Triomphe and marvel at the confidence of the cars and motorcycles that went shooting through into the centre of the torrid vehicular whirlpool, apparently reassured of coming out intact on the other side. The trees hid the great arch from us for a long time as we approached, but when it finally revealed itself it did so from the optimal three-quarter angle against the setting sun. The Champs-Élysées were more embedded with tourist magnets than anywhere else we had been so far, though still not nearly in the way London’s inner streets were earlier in the week. Untempted by the French versions of all the same shops we have in Australia, we re-boarded the metro and made for the lower streets of the Montmartre.

Our early evening was spent in the fromagerie Monbleu, where we entertained the French mode de vie properly for the first time with cheese and fresh bread and wine. We chose the Comté and the Napoléon and the Camembert—the restaurant selected the fourth cheese for us. All were incredibly delicious and distinct from one another, eaten in generous wedges on the pieces of crusty white, brown and fruited breads with scrapes of jam or slivers of pickle onion. Washed down with a glass of wine as darkness took hold beyond the heated interior, it was the perfect way to spend a Parisian winter’s late afternoon.

Our return walk took us through the second arrondissement and its arcades of historic bookshops and boutiques all the way to the Palais Garnier, where we witnessed the opera house’s façade lit up for night. We were quite full up on delicious cheese, so there was no discomfort in waiting up a while back at the hotel for our more classically French nine o’clock dinner booking, at a traditional bistro called Le Colimaçon. This was more my treat than Mum’s, as the vegetarian option —a melange of salad and roast vegetable sides ripped from the plates of the meat dishes—was so obscure it was not even menu-listed. I had steak tartare and frites, eaten with a reverence only broken by disbelieving glances in the direction of the couple sitting next to us, who we obsessed over most of the evening.

They were remarkable. This pair were young and loud and expensively English, as crass about their class of wealth as they were about the food; their topics of conversation, heard by the entire room, progressed naturally from the jewellery business to the selling of a hundred thousand pounds in shares to whether they should stay in Derbyshire to a completed unprompted tirade in defence of the British monarchy. The entire restaurant was turning its heads at intervals to look at this bizarre display of social caricature. They continued to entertain us throughout a dessert of crème brulée and chocolate mousse—both good, but the mousse particularly incredible, a pure mouthful of rich dark cocoa cream. Leaving this show of human oddity behind in the little bistro’s second-floor dining room, we returned to the chilly streets and to the platforms where the prompt arrival of the metro promised an easy journey home.

0 notes

Text

london-paris 11th december

On Sunday I got up early as usual and put on all my layers for a last walk around the freezing streets—everything was shut up for the half day, even the supermarkets. Luckily we still had bread at home leftover from Mum’s morning toast that I could use to make up my packed lunch I had planned in order to clean out the fridge a bit. I made salmon-cream cheese and ham-Marmite sandwiches and wrapped them in brown paper for the train. We closed up the apartment and battled our way through the London underground with our cases to King’s Cross-St Pancras, from where the Eurostar would take us beneath the Channel to Paris. Standing in the queue for passport control, we were already surrounded by the French—except for the family just ahead of us, who were Australian too, just more loudly so. Having survived the stringent security screening, French border agents working far from home waved us on through the gates and towards the train.

It was a fairly painless journey from there, before I even realised what was going on we were in France, crossing frosty countryside in the direction of the capital. At Gare du Nord I began to get more excited about the whole thing, since Paris was so unfamiliar to me, though there is so much about the city that intrigues me. We changed to the Metro and took it to the end of line 8—Place d’Italie, over on the other side of the Seine. The Metro was distinctly less dramatic and intimidating than I had remembered it being, perhaps because I was no longer seven years old. Our hotel is in Les Gobelins, down the hill from Place d’Italie and hidden away in a quiet side street. Hotel Henriette is a trendy sort of picturesque place which has developed its own idea of the Parisian lifestyle, which includes delicate floral décor and a small basket of viennoiseries kept on the coffee table in reception at all hours of the day. Our rooms are on the fifth floor, reached by a typically cramped, lethargic Parisian elevator.

Settled into our lovely accommodation, we headed out to see a little of the city in the evening and find dinner. We saw the towering Pantheon and the scaffolded skeleton of Notre Dame from pavements which felt oddly quiet, compared to the bedlam we had encountered on nearly every main London street. The hotel had offered suggestions of local restaurants, though many were closed on Sundays. I had my own ideas and led Mum on a slightly extensive walk through Paris to the 10th arrondissement, to a restaurant I had found whilst planning for Paris called Le Daily Syrien Veggie.