Parallel fifths in the works of common practice composers. Pictures of cats chilling out on scores.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

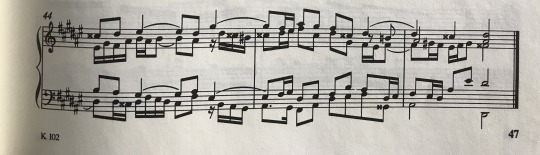

Mozart Piano Concerto K. 537, the so called "Coronation Concerto." If you play this bar very slowly, it sound like complete nonsense, replete with a parallel fifth.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

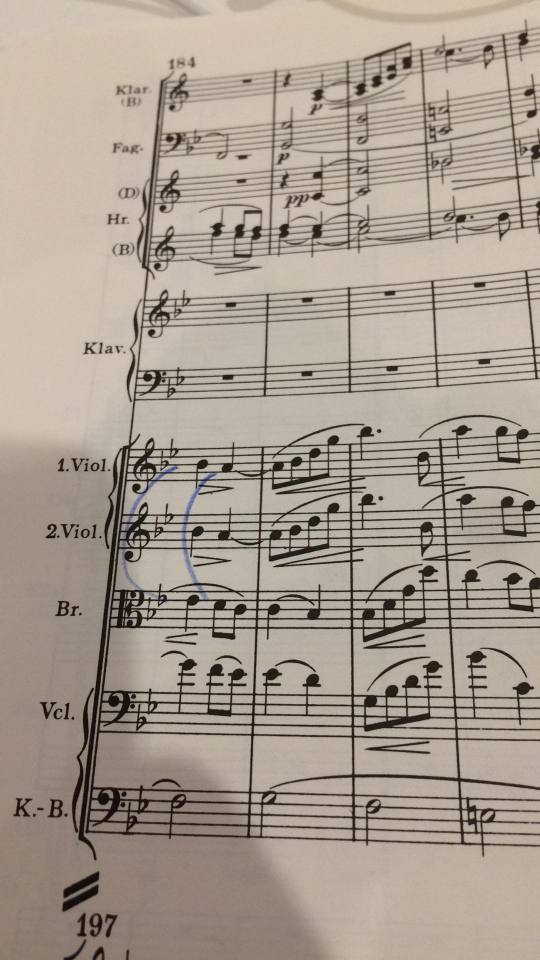

Voice Leading in Brahms 4

I’ve mentioned this before, but Brahms had a proto-blog like this one where he kept examples of parallel fifths and other voice leading irregularities that he found in the works of Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and others.

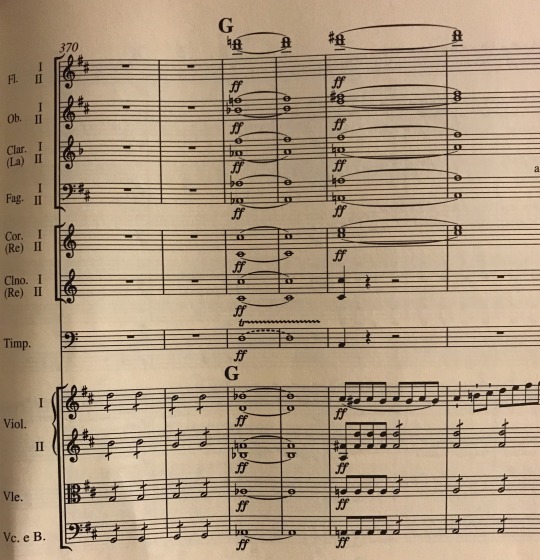

This post is about curious parallel fifths in the first movement of Brahms’ Symphony no. 4.

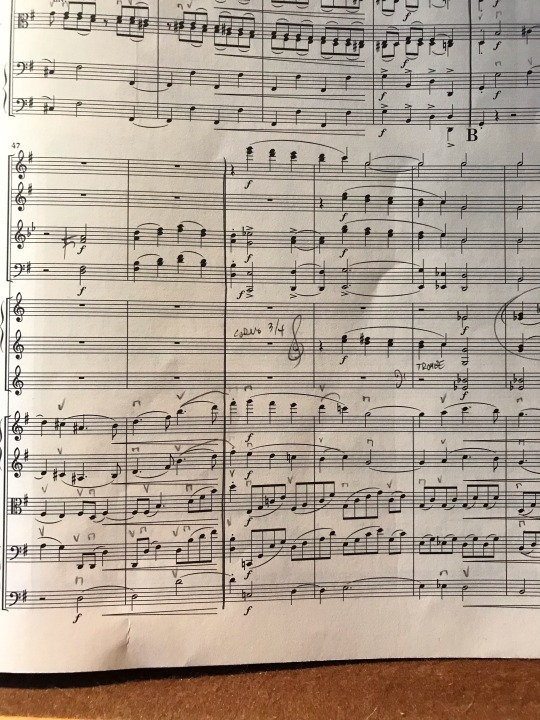

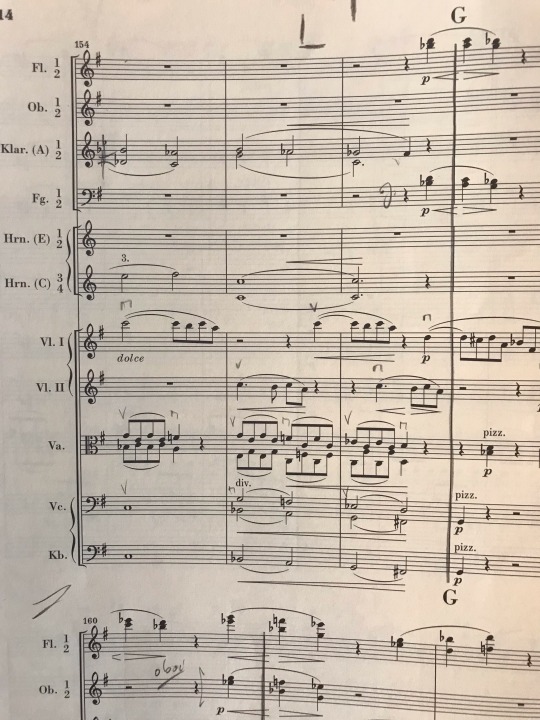

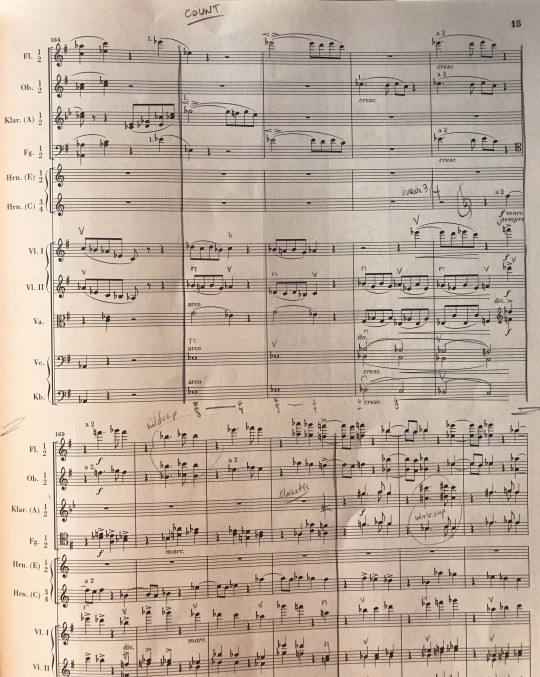

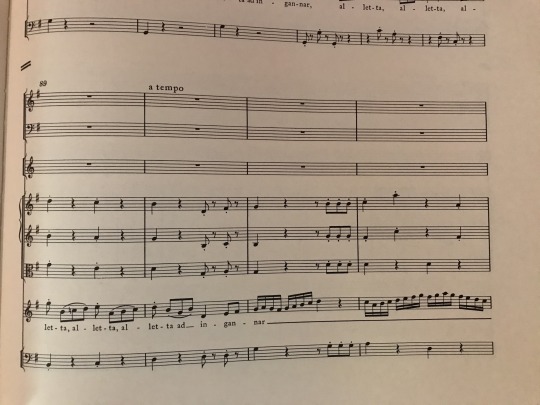

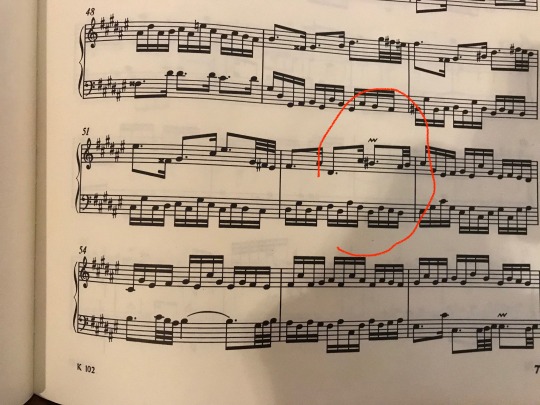

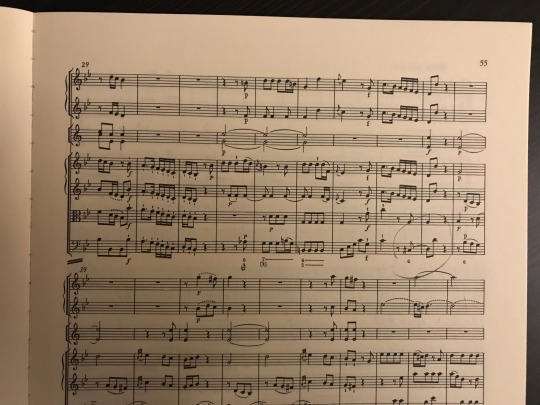

Check out bar 49 below. Parallel fifths between clarinet 1 and violin 1.

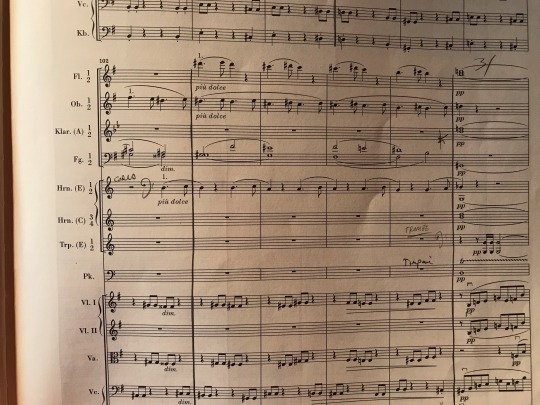

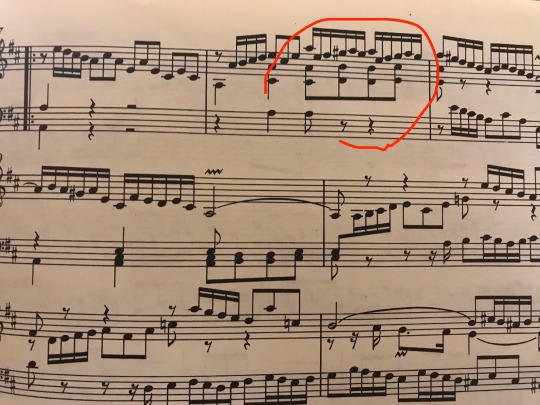

Below going into bar 105 between bassoon 2 and oboe 1.

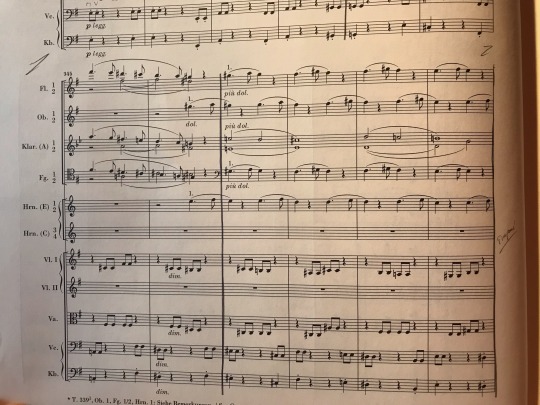

The corollary spot in the recap below. Going into bar 349, between clarinet 2 and oboe 1.

Below in bar 155. Between Violin 2 and the top viola.

A similar spot below in bar 167, between oboe 1 and violin 2.

And finally, a very interesting case below in bar 182. Going from beat 3 into beat 4, between bottom viola and flute 1, and then again going into the following downbeat, between horn 1 and flute 1/clarinet 1/violin 1/top divisi of violin 2.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bach and Beethoven Parallel Submissions

Submissions below from @jonathanalternate. I would argue that the first set might not really count because the top voice is actually a composite of two voices (one moving down, one an ostinato G-sharp), but he is right that in the moment, reading the notes, there are consecutive fifths by leap. The rest are all very interesting finds.

Hello, I recently came across this fantastic blog and I want to give some examples of parallels I have found.

Firstly, I have not one but four examples of parallel fifths from the Well-Tempered Clavier, and coincidentally all from the fugues. Let’s run them down one by one.

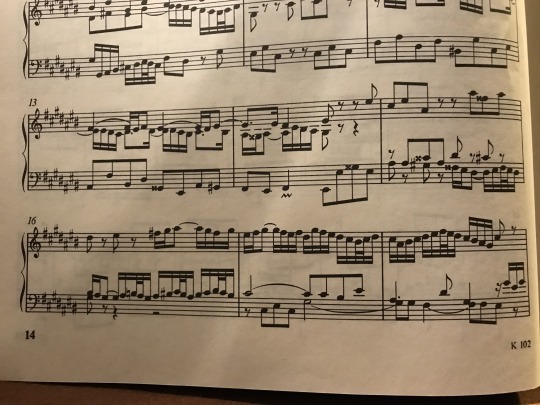

This first example is from the C-sharp major fugue from WTC I (BWV 848), specifically in the notably long episode of the latter half of the fugue. In the last bar of the system, bar 39, the bass leaps downward from a C# to a G#, and the soprano leaps in the same direction from a G# to a D#, creating parallel fifths. This occurs due to the G# pedal point in the soprano, and if said pedal point is removed, then we see the soprano simply moves down stepwise from E# to D#.

This next example is from WTC’s D minor fugue (BWV 851). In bar 15, the alto leaps upward from an A to a C natural, and the soprano also ends up leaping a third up, from E to G.

This third instance of parallel fifths comes from the ultimate B minor fugue of the first WTC (BWV 869). This example is a little harder to see due to the voice overlapping, but if you look closely at bar 22 you can see the soprano moves from a G# to an F#, while the bass moves from a C# to a B.

And our final Bachian example comes from WTC II, in the G minor fugue (BWV 885, which is personally one of my favourites from the WTC, but I digress). In bar 63, the soprano moves from an Eb to an F, while the tenor moves from an Ab to a Bb.

For a little bonus, I have an example from a Beethoven piano sonata. This is from his Piano Sonata No. 2 in A major (Op. 2 No. 2). From bars 56 to 57, the soprano and alto both move from a C natural to a B, creating parallel octaves. These parallel octaves can also be observed in the recapitulation section from bars 276 - 277.

And that’s it for me. Thank you for taking the time to read this, and have a good day.

Signing off,

Jonathan.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mozart’s Forbidden Chord, Part 2

In April 2018, I wrote a post about a special chord. In 2010, Carl Schachter, a professor at Mannes College, challenged anyone to find a “diminished third” chord in Mozart’s works.

My post from 2018 explored the possible instances of this chord in Mozart’s works, and dismissed them all as either copying errors from certain editions, or posthumous completions of Mozart’s unfinished works by others. The closest I could find was one awkward and brief use of the chord in an early symphony Mozart wrote when he was nine years old.

Now, the plot thickens. I haven’t found any more instances of the chord. Instead, I have found evidence that Mozart had a particular aversion to the chord.

In 1782, Mozart became immersed in the works of J.S. Bach, in part thanks to Baron Gottfried van Swieten, who shared copies of Bach’s music and organized reading sessions and performances of his works, which at the time were fairly obscure and considered old-fashioned. The impact of Bach’s works on Mozart’s style was enormous and readily apparent in the increasing contrapuntal complexity of his compositions beginning in 1782.

Part of Mozart’s study of Bach included transcribing and arranging Bach’s fugues. Bach used the “diminished third chord” in his works, including in the Well Tempered Clavier and the Mass in B-minor, so I wanted to see if there was evidence that Mozart encountered the chord in Bach’s works.

He did. Mozart’s K. 405 is an arrangement for string quartet of fugues from the Well Tempered Clavier, including the D-sharp minor fugue from Book II. Bach uses the diminished third chord in the final cadence, in the pickup into the final bar.

Mozart transposed the entire fugue down a half-step to D minor, presumably to make it easier to play for strings. His arrangement CHANGES THE CHORD IN THE PICKUP INTO THE FINAL BAR.

Notice he changes the top voice to a B-natural, whereas Bach’s original would have been a B-flat if it were transposed to D minor. Mozart then adds a C-sharp as a passing note up to the D in the final bar.

I would argue this is evidence that Mozart was aware of the chord, and didn’t like it.

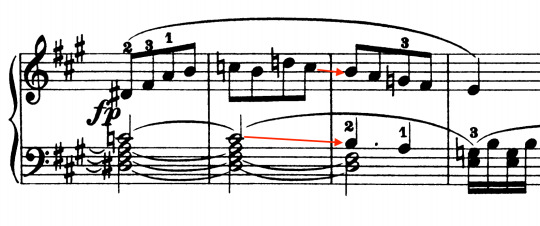

Also, unrelated, but here are two sets of parallel fifths in Beethoven’s piano trio opus 1 no. 3.

4 notes

·

View notes

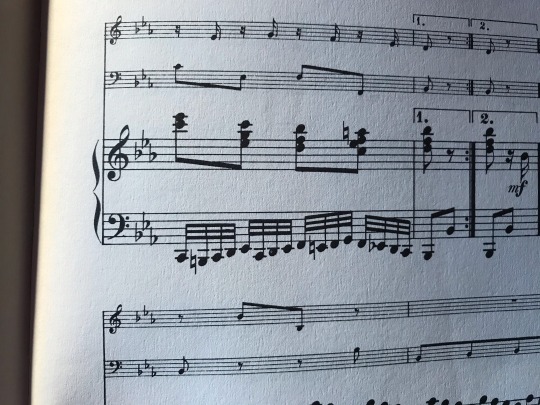

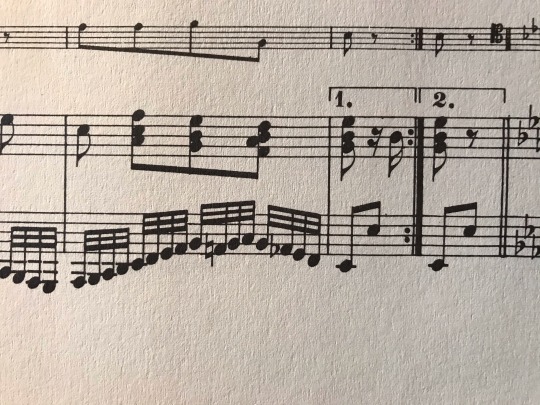

Photo

A rare sighting of parallel fifths in Brahms in their natural habitat. Scherzo of the F-minor Piano Quintet, bar 152. A-flat and E-flat to F and C.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mozart and Tchaikovsky

Do you know who Tchaikovsky’s favorite composer was? Correct; it was Mozart.

Some parallel fifths in works by both composers.

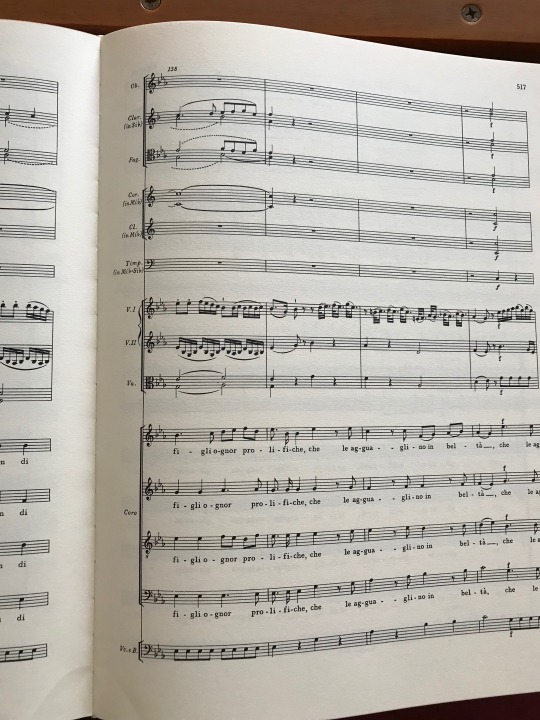

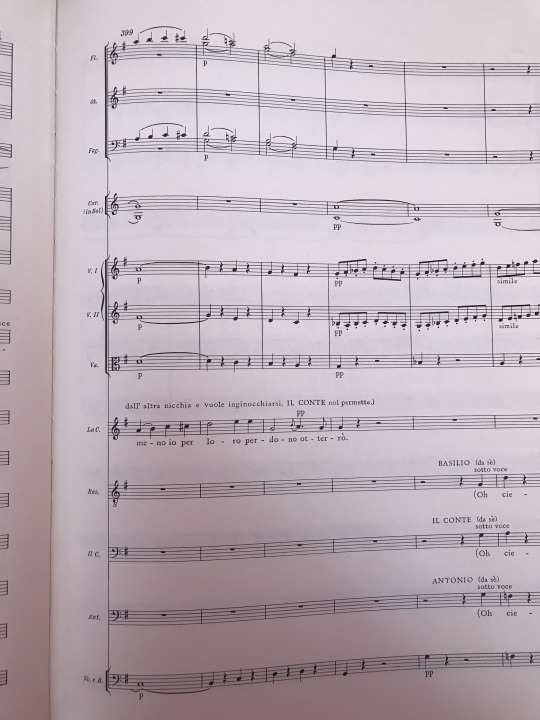

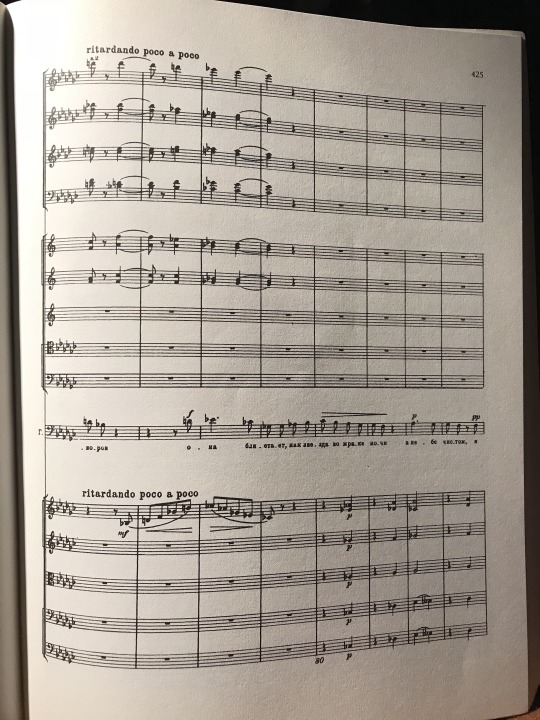

Così fan tutte, act 2 finale. Going into the second bar on this page, notice that the first violins have a B-flat embellished with C-natural neighbors. Choral tenor (and first basson/violin) descend from F to E-flat underneath.

Le Nozze di Figaro, act 4 finale. Going into the second bar of the page. F-sharp to G in second violin, C-sharp to D in Flute/Contessa (and first bassoon, but that’s underneath the second violin).

Clemenza di Tito. Vitellia’s “Deh se piacer mi vuoi.” In the second bar of the page: Viola goes from G to A. Above, Vitellia goes from D to E.

Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker.

Third bar from the end of the page. Bass line has a B-natural embellished with C-natural neighbors. Above, melody goes from G to F-sharp.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Least Parallel Composer

Johannes Brahms had a “blog” much like this one where he kept track of consecutive fifths (and octaves) that he found in the works of his favorite composers (Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven are all well-represented). Brahms’ style is very contrapuntal and he values the independence of voices in his writing. As a result, it is very rare to find parallel fifths in his works, but I bring you a few examples.

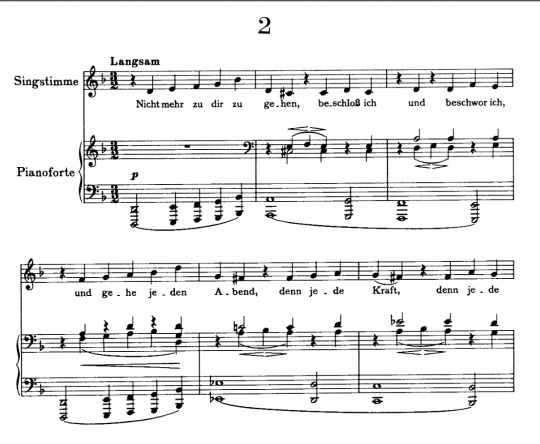

First, from a song: Nicht mehr zu dir zu gehen. From bar 5 to bar 6, between the voice and the bass.

Two examples from the cello sonata no. 1. In bar 83, the two piano staves have consecutive fifths, albeit by contrary motion... Same thing at the recap in bar 244.

An example from the last movement of the first piano concert, submitted by Maestro Stefano Sarzani.

And for something completely different, a Beethoven example, from the second movement of the Appassionata Sonata (Opus 57). From Bar 6 into Bar 7: blatant parallel fifths, even with the strange spelling. If he is going to use the B-double flat, then the “E-natural” really should be an F-flat.... Submitted by Maestro Miguel Campos Neto.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Submission from @Grossfudge

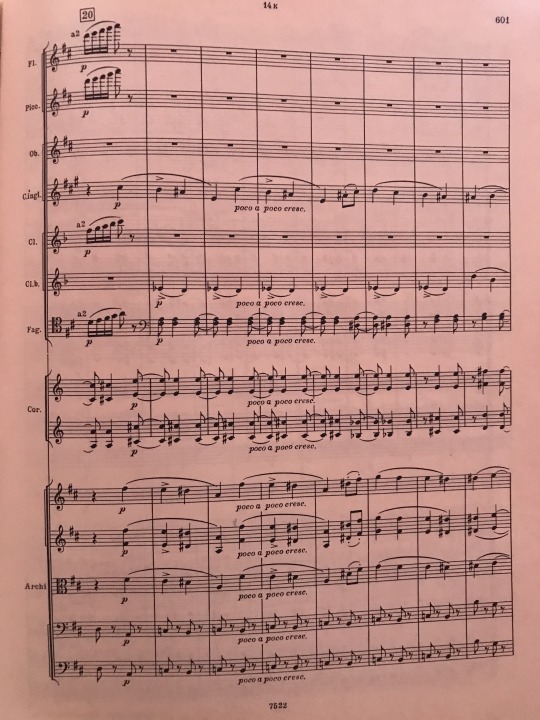

Verdi, Prelude to La Traviata, in the divisi first violins and the cellos in the second beat of the middle bar.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Mozart Submission from @Zimti-Blog

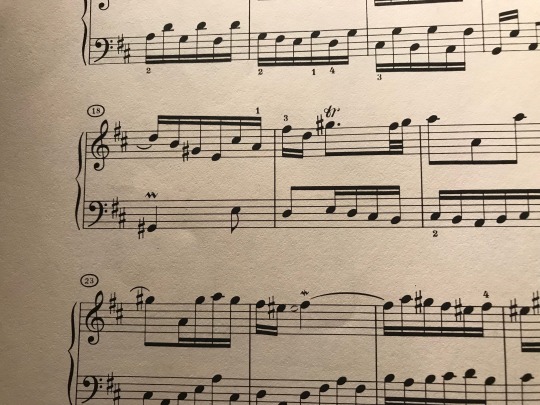

Hi, just discovered your great blog, seems you haven’t yet posted this parallel fifths from Mozarts KV 331, last mouvement “alla turca” (h-a / e-d):

0 notes

Text

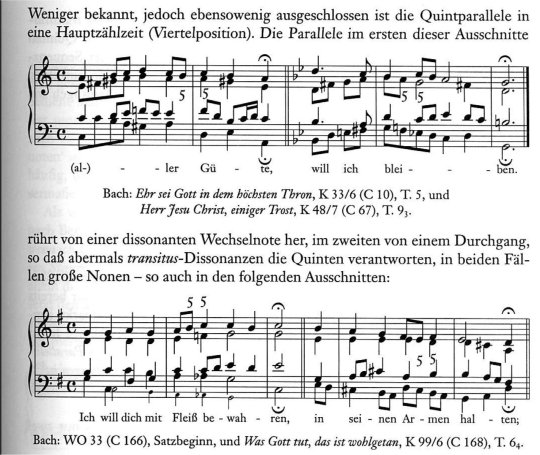

Bach Submission from @Zimti-blog

Hi, and here some more examples from Bach (I took this from the book of Thomas Daniel on Bach chorales, see the “5” markings:

all best,Johannes ([email protected])

1 note

·

View note

Text

Sorry for improperly using this form

“… But on the JS Bach wtc2 d maj example, you circle parallel SIXTHS, not fifths, or am I missing something?”

Thanks for getting in touch! The parallel fifths are from the penultimate eighth note of the bar (B and F-sharp on the final triplet), to the final eighth of the bar (C-sharp and G-sharp).

0 notes

Text

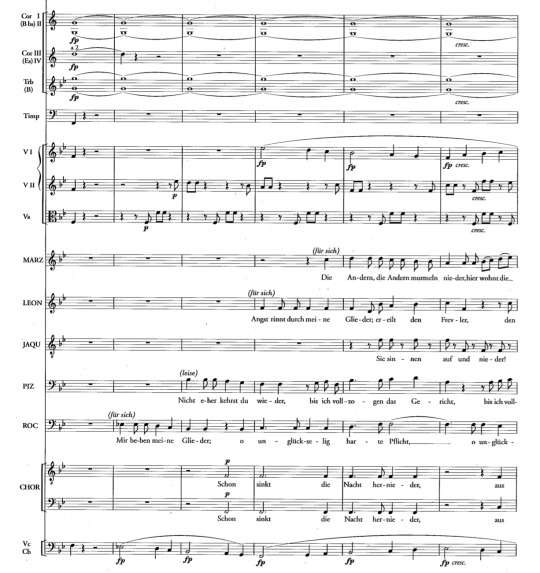

Beethoven and Bach

In honor of Beethoven’s birthday, some sort of parallel fifths in Fidelio! Towards the end of the act 1 finale, between the 4th and 5th bars of this example between violin 2 and Pizarro.

And some parallel octaves in the Bach Weihnachtsoratorium, in bar 65 between violin 1 and the bass.

0 notes

Text

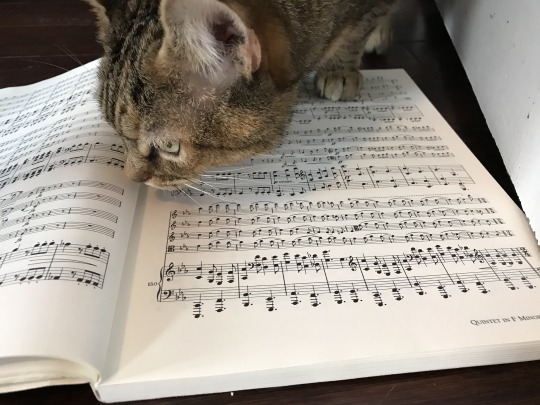

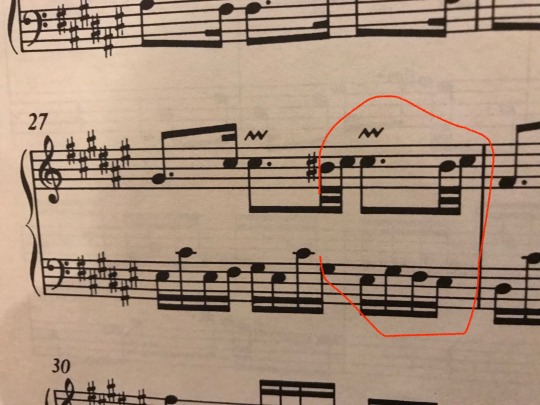

More fifths in Bach WTC II, and the softest spot in the repertoire.

Parallel Fifths in Bach’s WTC Book II:

Two spots in the F-sharp Major Prelude.

But there will be those who say “but those aren’t REALLY parallel fifths. They just arise from the written-out ornament figure at the end of the trill!”

Fair enough. How about these from the D-major Prelude?

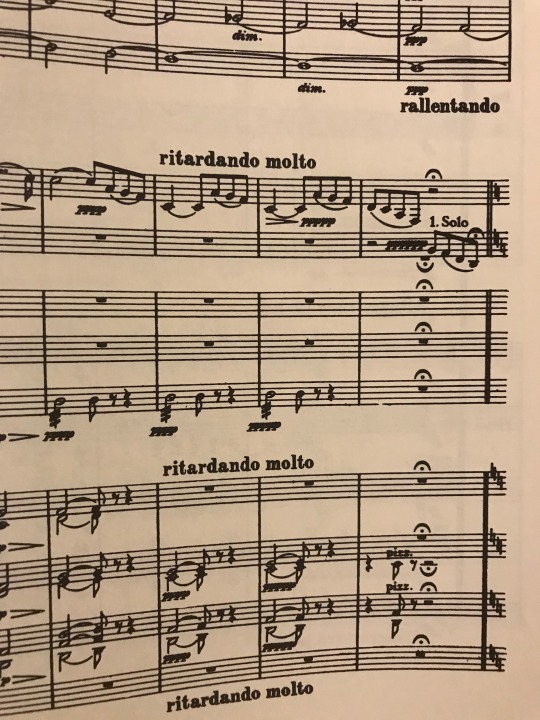

Completely unrelated. But we may have discovered the softest pianissimo in the entire classical repertoire. Many people assume that the softest spot is in Tchaikovsky’s Sixth Symphony, with a stunning six P’s. This spot is so soft that some people consider it impossible to play on the bassoon and call in a bass clarinet just to play these four notes.

But this spot from Verdi’s Trovatore is nearly three times as soft, with 17 P’s. When I first saw this I thought that the editor’s cat had just sat down on the keyboard and added a bunch of P’s that nobody caught, but the marking is consistent across the “traditional” Ricordi edition and the Works of Giuseppe Verdi Critical Edition from University of Chicago press.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The relationship between counterpoint and orchestration

Sometimes, orchestration can either mask or exacerbate voice leading issues. This post is going to explore some examples in Brahms and Tchaikovsky.

Consider this example from Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta:

Look at the outer voices for the first two beats on the page. The lowest sounding notes are first D (in the cello), and then C (in the viola, which jumps underneath the cellos!). As this composite bass line moves from D to C (albeit in different instruments), the melody (in the clarinet and corno inglese), moves from (concert pitch) A to G. Those are technically parallel fifths, but Tchaikovsky “hides” them by having the viola jump underneath the cellos. Tchaikovsky uses this technique extensively in his orchestration. Rather than stacking all the instruments in order from lowest to highest, he frequently has them cross, putting the clarinets between a low and a high bassoon, having low horns fill in a chord between tuba and trombones, etc. This is a general technique of the Russian School of orchestration, that results in a pleasant mix of timbres. Read more about this in Rimsky Korsakoff’s Principles of Orchestration.

Notice that also in the final bar of the above example, the composite bass line starts in the viola on B-flat, and then the cellos “continue” that line with an A-flat. Against this motion of B-flat to A-flat, the melody in the first flute and oboe goes from F to E-flat, again generating parallel fifths. Above the cellos and violas, the violins engage in some acrobatic voice leading, crossing and exchanging notes. This is tangential, but Tchaikovsky’s use of the violins in such a matter strongly suggests that in his time, the two violin sections in the orchestra still sat split on the left and the right, rather than lumped together to the left as they are in many modern orchestras. By passing lines between the two antiphonal violin sections, Tchaikovsky was creating a stereo effect. The best example of this is the final movement of his Symphony no. 6. If the violins sit split, then the descending line from F-sharp that starts in the second violins gets passed back and forth between the two sections.

Back on track, I must confess that in the previous bar in this same section of Iolanta, Tchaikovsky presents the same material, but this time has unapologetic direct parallel fifths between the bass line (which does not jump between instruments, but just stays in the cellos), and the melody in the flute and oboe.

Why? It’s hard to say. But I think that Tchaikovsky had a keen ear for overall orchestral sonority, and he valued the spacing of chords and the mix of timbres of any specific situation above strict counterpoint and independence of voices.

Later in the same passage he again writes direct fifths by keeping the bass line in the cello rather than transferring it between the cello and the viola. It’s really hard to say why he uses the orchestration to split the bass line in some situations and doesn’t in others....

To demonstrate Tchaikovsky’s priority of spacing and timbre, consider another example. This one from Onegin.

Going into the third bar of this passage, the bassoons have direct parallel fifths. Tchaikovsky could have avoided this by having the first bassoon on A-flat, resulting in a line from A-flat to G-flat, or by having the F as written descend to E-flat. But notice that the bassoons interlock with horns one and two, and double horns 3 and 4 (which resolve without parallel fifths). The overall effect on the ear is not offensive in the slightest, perhaps because the specific timbres of the instruments on these specific notes blend well.

This is admittedly a very subjective process. When does it sound better to avoid parallel fifths? When does it sound better to prioritize the spacing and timbres, even if it generates parallel fifths?

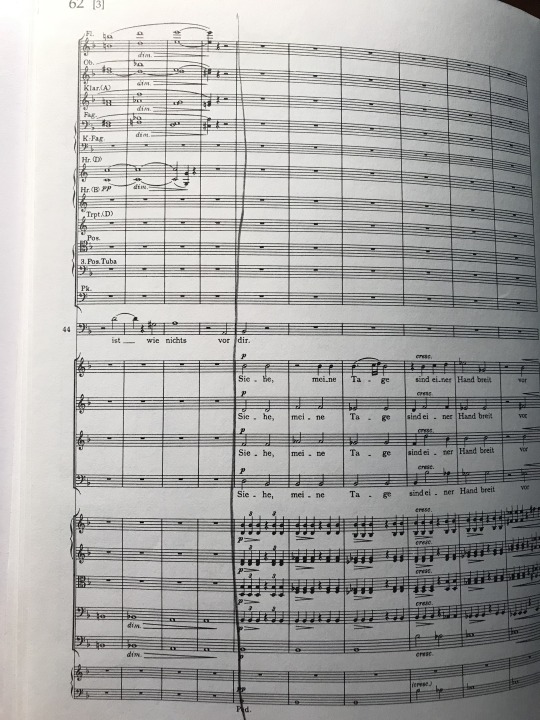

Consider this example from Brahms Ein deutsches Requiem:

Going from the second bar into the third, we have a German augmented sixth chord that resolves to a dominant “5/4″ chord (in figured bass notation). This is usually a no-no. Because the bass of the German augmented sixth almost always resolves down by a half-step, the voice a fifth above the bass cannot also resolve down, so German sixths usually resolves to dominant 6/4 chords. However, in this situation, Brahms does something very Tchaikovsky-esque. Bassoon 1 leaps from a B-flat to an E-natural, as does oboe 1. Similarly, clarinet 1 leaps down to the concert E-natural, from D; only the flutes approach the E parsimoniously, from below, which does not generate parallel fifths. Whereas Tchaikovsky masked his parallel fifths by passing them between two different instruments, Brahms passes the composite line “F, E” between two of the same instrument; so one can still kind of hear a bassoon timbre playing “F-E,” an oboe timbre playing “F-E,” and a clarinet timbre playing “F-E.” However, because the flutes resolve upwards to the E, and they are the outer voice, I don’t think the parallel fifths in the middle timbres are very apparent. In some sense, passages like these represent the tension between the “letter of the law” (not writing parallel fifths between two instruments), and the “spirit of the law,” (maintaining independent contrapunctal lines instead of “power chords.”)

What do you think? Do you like how these passages sound?

1 note

·

View note

Text

The forbidden chord that Mozart only used once

8 years ago, when I was studying at Mannes College, Professor Carl Schachter, one of the giants of music theory, issued us a challenge one day. He said that in Mozart’s entire oeuvre, he never used a “diminished third” chord, and he challenged us to find one that Mozart wrote.

A “diminished third” chord is an inversion of an augmented sixth chord, and in isolation it sounds the same as a dominant 4/2 chord. In a normal augmented sixth chord, the augmented sixth resolves out; the bass moves down, and the augmented sixth above the bass moves up. But in a diminished third chord, the resolution is inwards: the bass moves up, and the voice with the diminished third above the bass moves down.

This chord is one of Tchaikovsky’s favorites. Below is an example from the slow movement of his Fifth Symphony. Note the E-sharp in the bass that resolves up to an F-sharp, while the G-natural in oboe 2, clarinet 2, horns 2 and 4, and trombone 2 resolves down.

Tchaikovsky used this chord to great effect in his operas as well. Below are two examples from the final scene of Onegin. Note the A-sharp in the bass resolving up.

And here are two examples from Lenski’s aria, also with A-sharp in the bass.

Another interesting example from Lenski’s aria. The diminished third is presented in middle voices (horn and cello), but still resolves in rather than out.

Tchaikovsky used this chord no less than 26 times in his opera Iolanta, so much so that it is practically motivic. The opera deals with contrasts of darkness and light. The only place where the chord doesn’t appear is in the big duet in which Vaudemont reveals the truth about light to Iolanta. With the chord’s dark sonority, perhaps Tchaikovsky used it to conjure a dark sound world. Below are the 26 examples.

Brahms also used this chord extensively. Two examples below from the E-minor Cello Sonata.

Brahms Piano Quartet in C-minor.

Brahms Piano Quintet in F-minor (Scherzo). Like the example from Lensky’s aria, the ascending note is not the bass, but the interval still resolves inwards.

Beethoven used the chord as well. An example from Fidelio. Note the A-flat resolving up. This chord is written as a dominant 4/2, but it could also have been written with the A-flat as a G-sharp.

Another Beethoven example, with the same spelling and function, from Symphony no.2.

So, perhaps this chord just wasn’t in use until after Mozart’s time. Perhaps it was pioneered by Beethoven’s revolutionary tendencies?

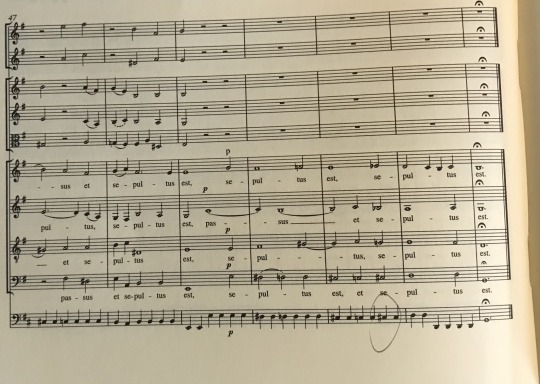

Not so. Here is an example from Bach’s Mass in B-minor. The end of the Crucifixus.

And another example by Bach. From the end of the D-sharp minor fugue in WTC Book II.

So this brings us to the interesting part. Did Mozart ever really use the chord?

Here is an example from the Lacrimosa of his Requiem.

Note that the chord is spelled like a dominant 4/2 (with the exact same pitches as the Beethoven examples), and that the A-flat resolves up. However, this passage was not written by Mozart. It was written by Süßmayr, who completed the piece after Mozart died.

Consider this example from the Linz Symphony (Breitkopf edition). Note the B-natural in the bass resolving up, as the D-flat in the viola resolves down. Could we have found the chord at last?

Unfortunately not. This is a misprint. Compare with the same example from the Neue Mozart Ausgabe. The D-flat in the viola is actually a D-natural.

But at long last, I have found an actual example:

This is K.22, Mozart’s Symphony No. 5. The C-sharp resolves up, and the E-flat resolves down.

I just got off the phone with Carl Schachter. He said “If you find any more let me know.”

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

More parallel fifths in WTC

WTC book II, C-sharp Major Fugue. Between bars 15 and 16. Top voice goes from A-sharp to D-sharp, bass goes from D-sharp to G-sharp. Granted these are contrary motion by a leap, so it could be worse.

0 notes

Text

Actual parallel fifths in Bach

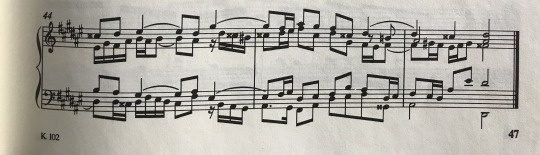

So my recent post about quasi-parallel fifths in the Well Tempered Clavier generated some controversy... Below are some that are still kind of controversial, but much less so. From the gigue of the French Suite no. 3. Bar 19. The right hand moves from the G-sharp trill to to the F-sharp as the left hand moves from C-sharp to B. These are similar to a set I mentioned a while ago in the WTC book two final fugue.

1 note

·

View note